Making Pictures Move

Related Resources

Making Pictures Move

The nineteenth century saw many attempts to animate and project images for amusement and edification. Educational toys such as Milton Bradley’s colorful “Historiscope” configured a set of lithographs into a scrolling frame, which allowed a child to seamlessly present one scene after another to family and friends. Such panoramic devices embodied the period’s impulse to transform a series of images from a static, two-dimensional experience into a dynamic performance. Magic lantern shows, for example, sequenced painted or photographed images as the projectionist added sound effects, narration, and other personal touches, coalescing the individual images into a cohesive presentation. The desire for moving performance was paralleled by early experiments in three-dimensionality. A forerunner to the nineteenth-century stereoscope viewer was the zograscope. This optical device for magnifying engravings enhances the sense of depth shown in the picture, bringing images of other places and peoples to life. Devices like these provided semi-immersive experiences which simulated colorful movement and depth well before moving pictures became technologically viable or commercially available.

“The Historiscope: A Panorama and History of America,” Milton Bradley & Co., [ca. 1868-1878].

This miniature moving panorama features a mechanism that allows the user to scroll through American historical images in chronological order. The ability to transition seamlessly between images represented a significant precursor to later modes of cinematic storytelling.

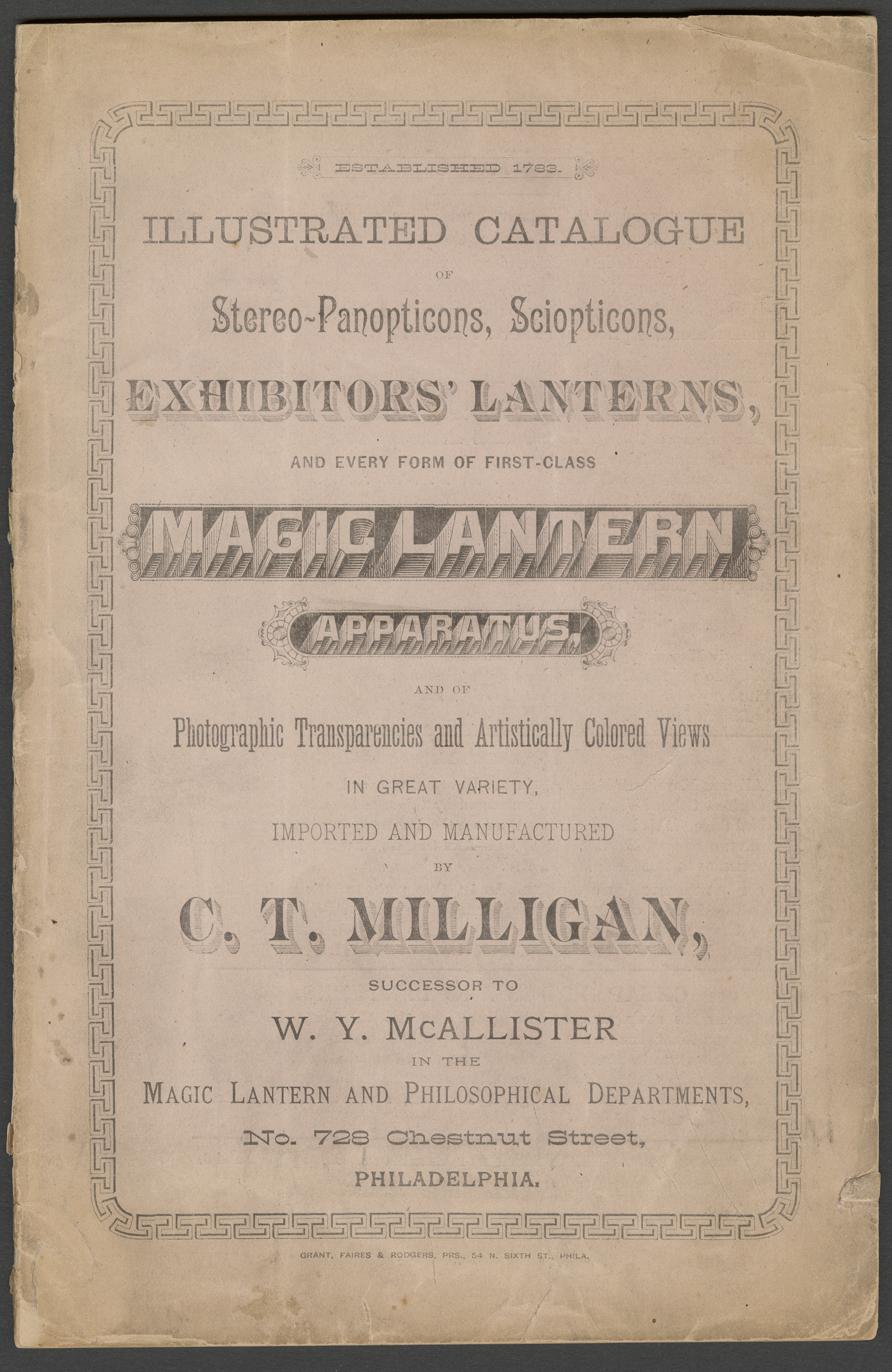

The Model Gloria was a lantern toy illuminated by oil light that projected colorful glass slides. Manufacturers such as C.T. Milligan produced trade catalogs advertising the variety of thematic slides available for projection in “magic” lanterns of all shapes and sizes.

C.T. Milligan, Illustrated Catalogue of Stereo-Panopticons, Sciopticons, […], and Every Form of First Class Magic Lantern Apparatus, Philadelphia: Grant, Faires & Rogers, [1880].

When inverted and viewed through the zograscope, an optical device designed to provide the illusion of depth to flat images, this ‘vue d’optique’ print of Havana Harbor appears three-dimensional. This combination reveals the 18th-century fascination with depth and realism in images, demonstrating early desires for captivating visual experiences that long predated cinema.