TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

Cramped, Crabbed, and Micro-Calligraphic

Cheney Schopieray

Curator of Manuscripts

Rebecca Dodge Eaton’s handwriting diminished in size from a moonlit base-to-waist height of over 3mm, to her average typical height of ~2mm, to a cramped 0.5–1mm height.

Teacher and poet Rebecca Dodge Eaton (1796–1852) sat down to her diary in the night hours of July 30–31, 1839, to the sound of the waterfalls in Rochester, New York. She had been experiencing “not very fine feelings” alone in the boarding house where she lived, but this night she found inspiration in the glowing light of the moon. Thanks to its reflection, she could see just well enough to write out feelings and religious praises into a blank book that she filled with diary entries, poetry, and miscellany. Still, her desk was steeped in shadow and her writing became shaky and almost twice as large as usual. Over the ensuing 26 days, she diarized on the same page, recording visits to the library, buying a “philopaena” gift, purchasing books for herself, reading, and attending lectures. Since she previously filled the reverse side of the page with poetry, she wrote smaller and smaller as she attempted to squeeze in as much writing as possible to put off the inevitable need to continue her diary somewhere else in the journal.

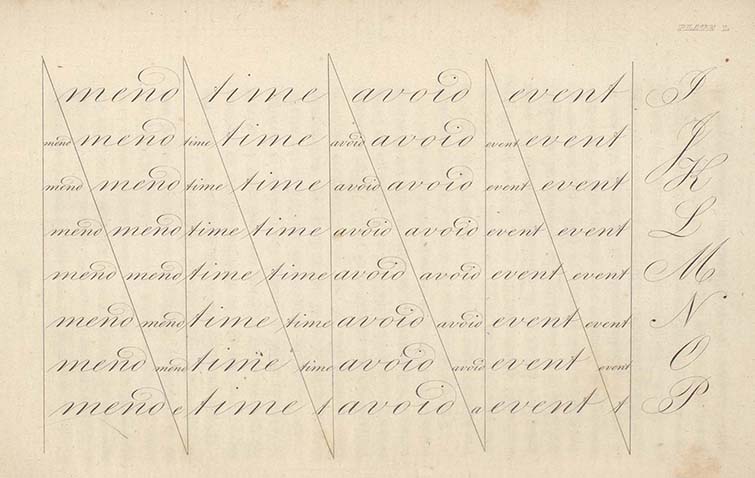

The influential Foster’s System of Penmanship (Boston, 1835) outlined a model for teaching students to write quickly, legibly, and with few frills. This plate shows teachers a method for using connected vertical and parallel lines for practice writing the same words in varying sizes.

Many overlapping reasons contribute to the size of a person’s handwriting. It may depend on the environment in which they write, their education and practice, their anatomy and physiology, the available writing utensils and surfaces, the purpose of the writing, and the intended audience. Viewing small handwriting seems to lead us naturally into asking usual questions of analysis: who made this? how did they make it? for whom? where, when, and why? Rebecca Eaton did not set out to write in an enlarged or a cramped script. Her handwriting changed size because of the presence/absence of light in her writing space and how she chose to keep her book—by adding text to seemingly random middle pages rather than sequential ones.

Penmanship education of the 19th and 20th centuries frequently included practices intended to hone students’ skills at writing letters and words with different forms, proportions, and spacing. Typically, younger children were (and still are!) taught to write large and only after gaining proficiency write smaller and smaller. Penmanship instructor Benjamin Franklin Foster (ca. 1803–1859) suggested a practice that moved from large hand to half text to small hand.

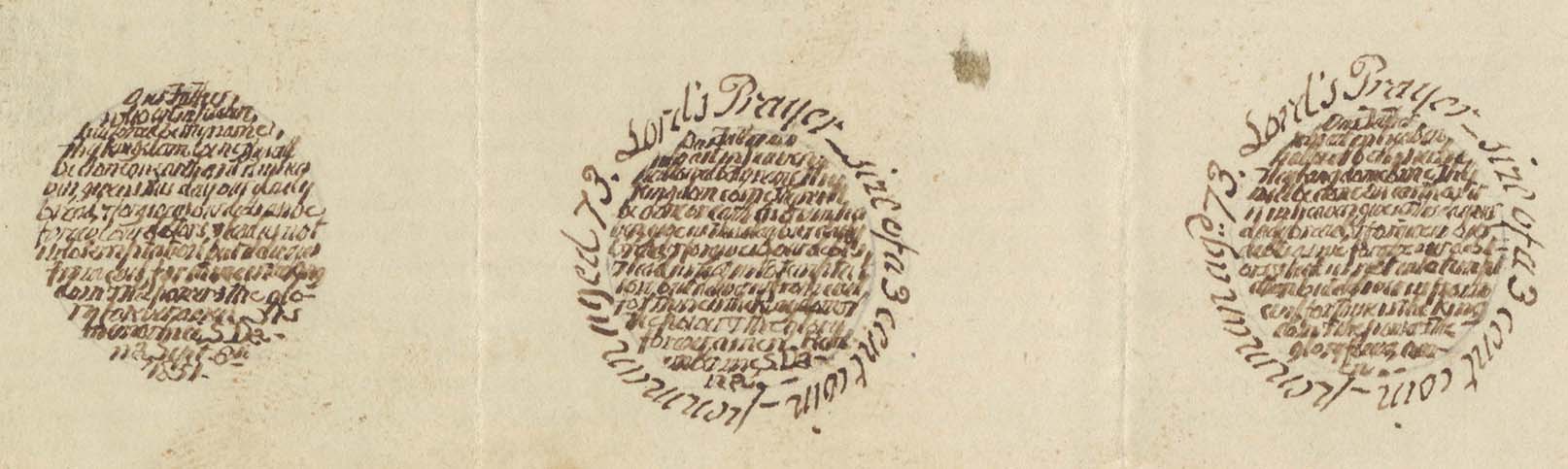

Magnification of these handwritten copies of the Lord’s Prayer reveals tracings of a coin used as a guide for the boundaries of the text. While vision typically diminishes with age, septuagenarian Rev. Samuel Dana defied the odds by producing legible writing with base-to-waist heights as small as 0.25 mm!

Some writers developed a habit or style of writing in a miniature hand as part of their everyday practice. Rev. Samuel Dana (1778–1864) of the Old North Church in Marblehead, Massachusetts, had famously small handwriting that he would use in his private writings as well as in service of his ministry. One of his routines was to take half dimes or three-cent coins, trace them with pencil, write the complete Lord’s Prayer in ink within the boundaries, erase the pencil, and give the results to friends or parishioners as keepsakes. The Clements Library has an example of three uncut, apparently undistributed examples that he created on September 6, 1851, at the age of 73!

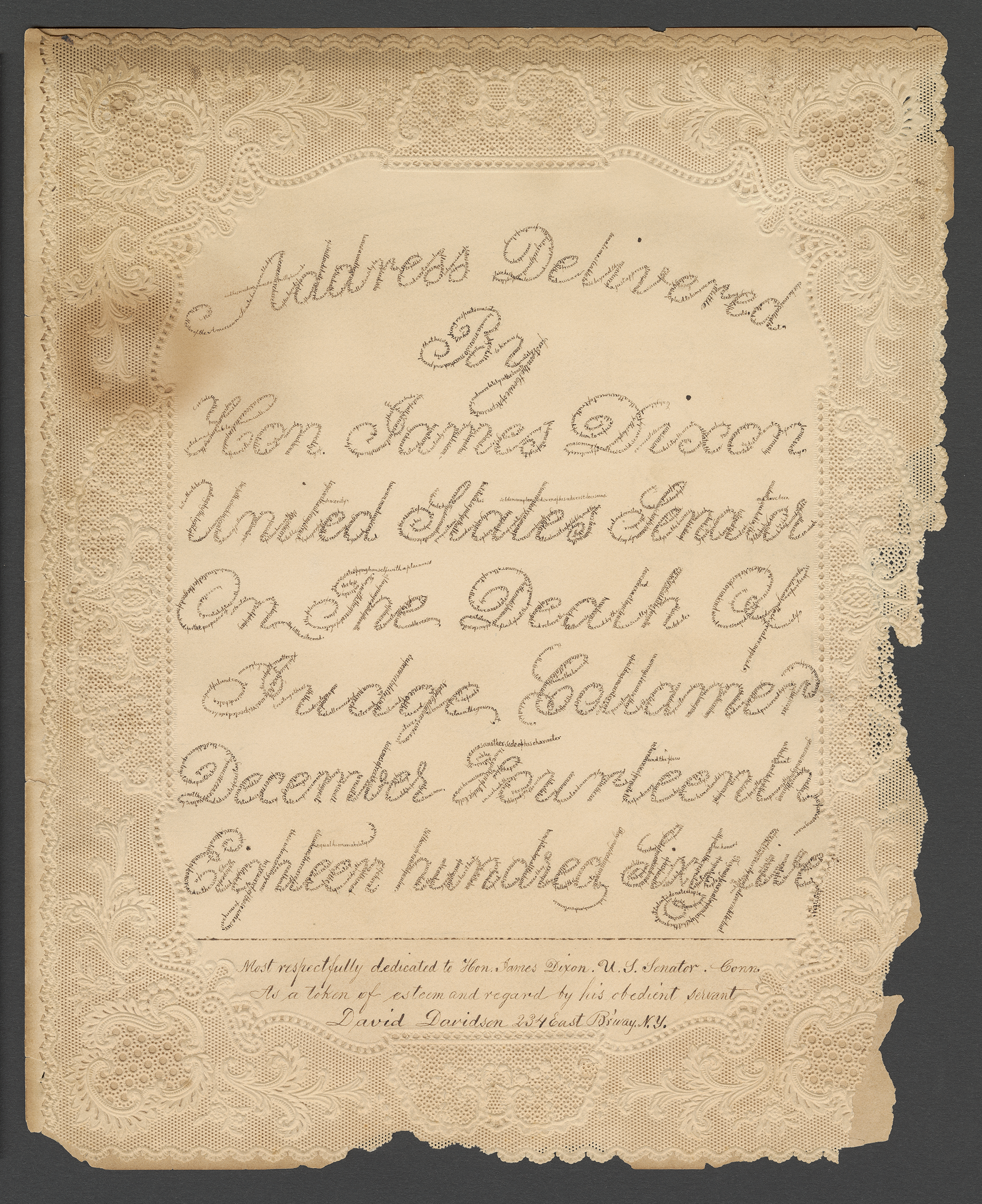

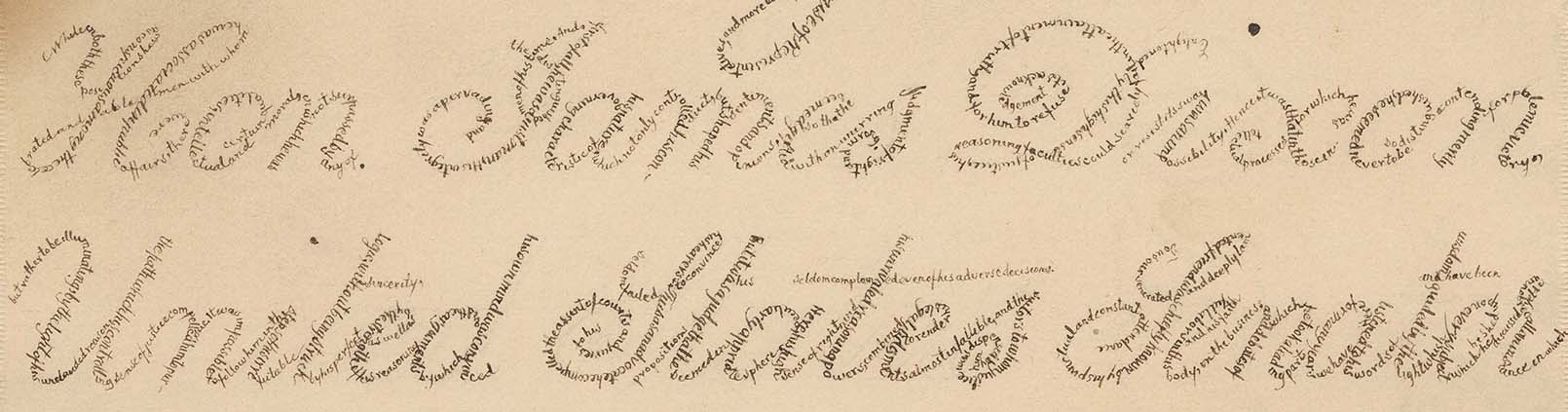

Micro-calligraphic writing might also have commercial motivations. The practice, skill, and talent of penmanship master and printmaker David Davidson is revealed in one example of his work. On ornate lace paper he utilized a “crow quill” steel pen nib to make a gift for U.S. Senator James Dixon, in recognition of his “Address Delivered . . . On The Death Of Judge Collamer” on December 14, 1865. When magnified, readers can see that title letters are comprised of the text of the speech. Davidson made a number of these works of art, which displayed his prowess to friends and potential penmanship students alike.

Micrography is a Jewish art form dating back to medieval times, using miniscule script to create shapes or drawings. Practitioner David Davidson, who referred to himself as an “artist in penmanship,” was born in Russian Poland and immigrated to New York in 1851. Other examples of his work include a micrographic drawing of the Astor Library and two portraits created using text from the Bible.

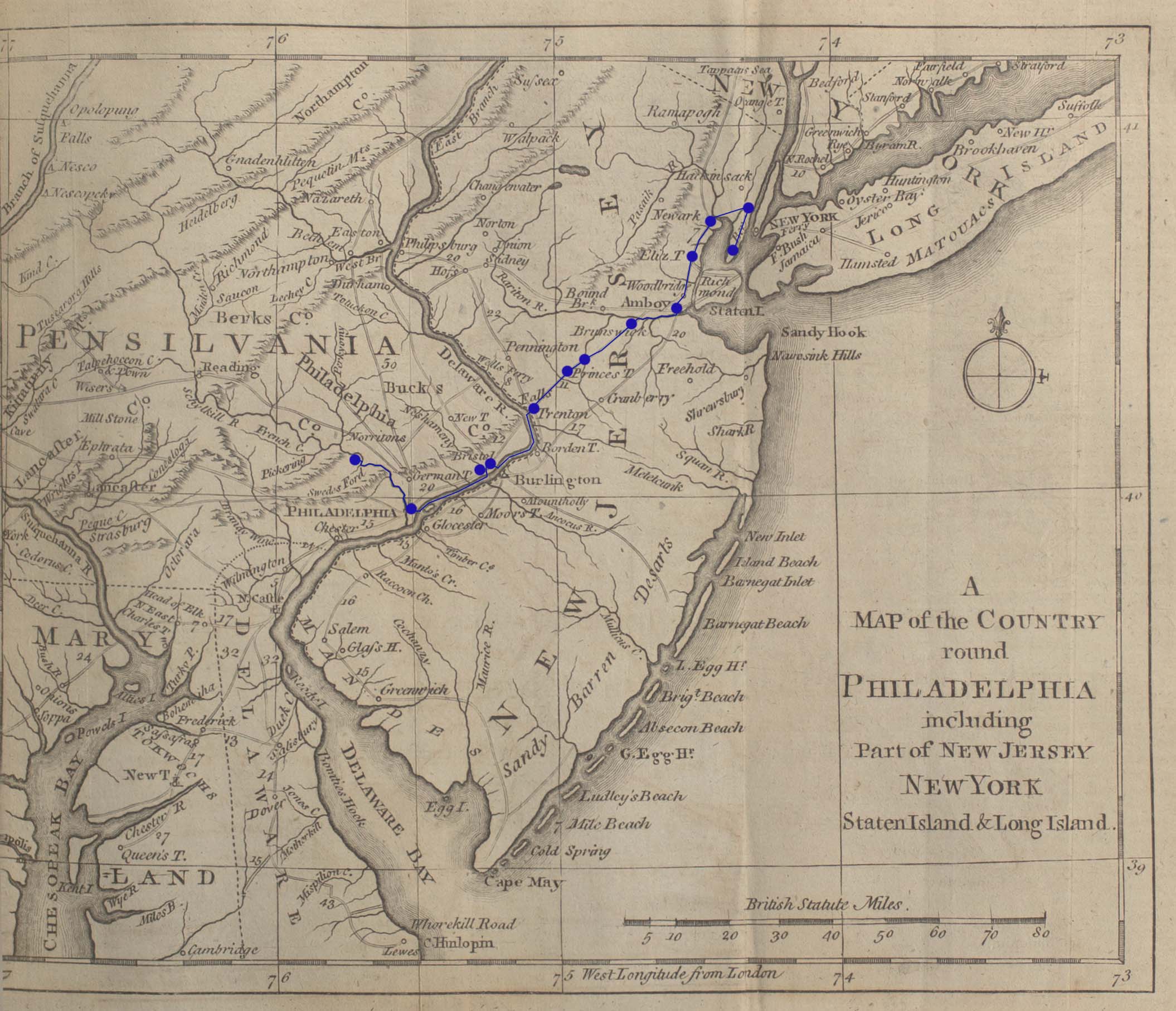

Tiny handwriting is perhaps most prevalent in pocket diaries and pocketsized notebooks, the sort which travelers often used for their portability These little books are practical for a person on the move, but! Taking up one of these home-made or pre-printed volumes also steels a commitment to small script or lettering. In 2020, Richard King Thomas donated his ancestor’s simultaneously diminutive and grand American Revolutionary War diary. The penman was a member of the Davis family of Upper Merion, Pennsylvania, a community roughly 15 miles northwest of Philadelphia. Though his identity is not yet known, the diarist was one of the men recruited for military service between June and August 1776 to assist in the defense of New York.

Extensive research has uncovered much information relating to this journal kept by a Pennsylvania militia member, but not yet his exact identity. The item is currently known as the Davis Revolutionary War Diary.

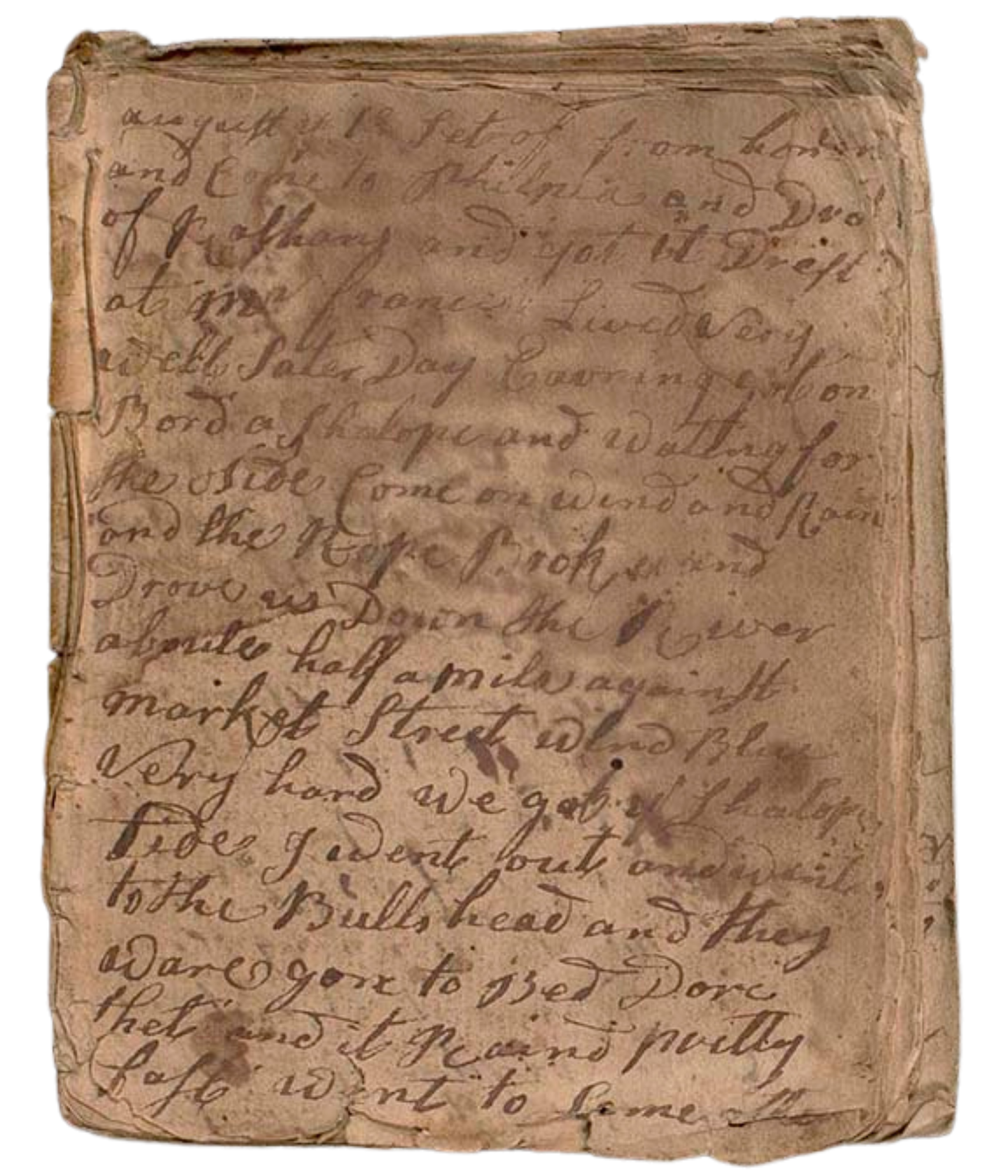

Davis was a militiaman or associator who took up a 10 × 8 cm hand-sewn volume of 34 pages and marched from his family farm on August 13, 1776. His handwriting is crabbed, a sort of cramped writing that is particularly challenging to read because of irregular character formation. With characters averaging ~1 mm base-to-waist height, the writer was able to fit as many as 20 lines on a page. His phonetic spelling adds to the importance of this documentation of his experiences. Davis carried the diary as he boarded a shallop in Philadelphia on August 17, 1776. That day, it survived the wind, pouring rain, high tide, and broken ship tie rope that stymied the departure and it stayed with him in a hayloft that night.

As he marched and sailed toward the City of New York, Davis kept hauling out his quill and a portable inkwell, writing on the most suitable hard surfaces he could find. He chose a large tombstone in an Elizabeth Town cemetery to write on as he passed through. Davis arrived at Bergen, New Jersey, the day after George Washington’s retreat from Brooklyn on August 30, 1776. Through the first two weeks of September, he moved with his battalion along the New Jersey shoreline, where he could see the British troops at work on Staten Island and hear the guns as they pressed in on Washington’s headquarters at New York. There, while moving between Bergen, Paulus Hook, and Bergen Point, Davis wrote about the oppressive mosquitoes, knee-deep mud, skirmishes between British Men-of-War and revolutionaries’ row galley boats, a woman who spared room for lodging, the sermons he heard, and his shifting diet (of chocolate, boiled beef, dumplings, bread, butter, pigeons, squirrels, and sugar).

Cramped, crabbed, micro-calligraphic, and just plain miniature handwriting can be a challenge to read and at times frustratingly opaque to the reader. It can also be awe-inspiring and beautiful. Or both at the same time. Asking “Why does Rebecca Eaton’s writing start large and then get smaller?” leads to thoughts about the space and conditions in which she wrote, as well as about her decision to use the blank book as she did. Saying “Wow!” and then asking, “Why would Samuel Dana make those little coin-sized prayers?” makes us think about Rev. Dana’s skills, motivations, and recipients. The stunning work of David Davidson draws us into questions about his practice, writing instruments, and audience. And considering the diary of American Revolutionary soldier Davis reminds us that the choice of writing surface may determine how small we have to write, whether we would prefer it or not.

Between August 17 and 21, 1776, Davis traveled with his diary from Philadelphia to Trenton; marched 26 miles or so through Prince own (Princeton), King’s own, and Brunswick; and then took the Raritan River to Amboy. A few days later, his unit moved to Elizabethtown, then Newark and Bergen. Between August 31 and September 12, Davis moved back and forth between Bergen, Paulus Hook, and Bergen Point. He then followed the same route home to Upper Merion, Pennsylvania, arriving there September 17, 1776.