No. 53 (Winter/Spring 2021)

Embracing Online Possibilities

It is perhaps an understatement to say that my first year as Director at the Clements Library has not gone precisely how I had expected. Since the library closed in mid-March, so many people have told me how hard it must be to have stepped into a new job, in a new city, under these circumstances. And it has been hard—for me, and for everyone else on the staff—to not be able to do what the library is set up to do. The Clements exists to provide opportunities for students, faculty, and researchers from around the world to have in-person encounters with physical artifacts from the nation’s past. That mission is what animates the talented staff of the Clements Library, and it is why generous supporters over the past 97 years have donated items to the Clements—so they would be used. Since March, we’ve had to work to find ways to replicate that experience remotely, over Zoom and through digital surrogates of collections materials.

But while these past 11 months have been hard, compared to so many others, I have had this year easy. The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated communities across the United States, and has killed over 500,000 of our fellow citizens. It has changed almost everything about how all of us work, and play, and worship, and mourn. Millions of Americans—myself included—have lost family members to COVID-19, and the endless upward progression of terrible numbers has made all of us wonder if 2020 would ever actually end. Even so, I have been reminded every day of how lucky I am, to be working with the marvelous collections of the Clements Library on the campus of a world-class university with a group of dedicated, deeply knowledgeable colleagues. Collaborating with them to build on the library’s great strengths and to discover new ways to introduce our collections to students and scholars under challenging circumstances has been a constant joy.

We do our work in different ways, from different places, and wearing different shoes (if any), but the core work of the Clements Library remains the same. And my colleagues at the Clements have been endlessly inventive and persistent in finding ways for the library to continue offering students and researchers the opportunity to study all aspects of American history and culture before 1900. Of course, the materials in the Clements collections can do more than just tell us about the history of a single nation. The questions that our collections help scholars answer are the great questions that have animated all humanistic inquiry: What constitutes a good life? How do we create meaning out of suffering? What is the right relationship of the individual to the state? What are the responsibilities of those with more power to those with less?

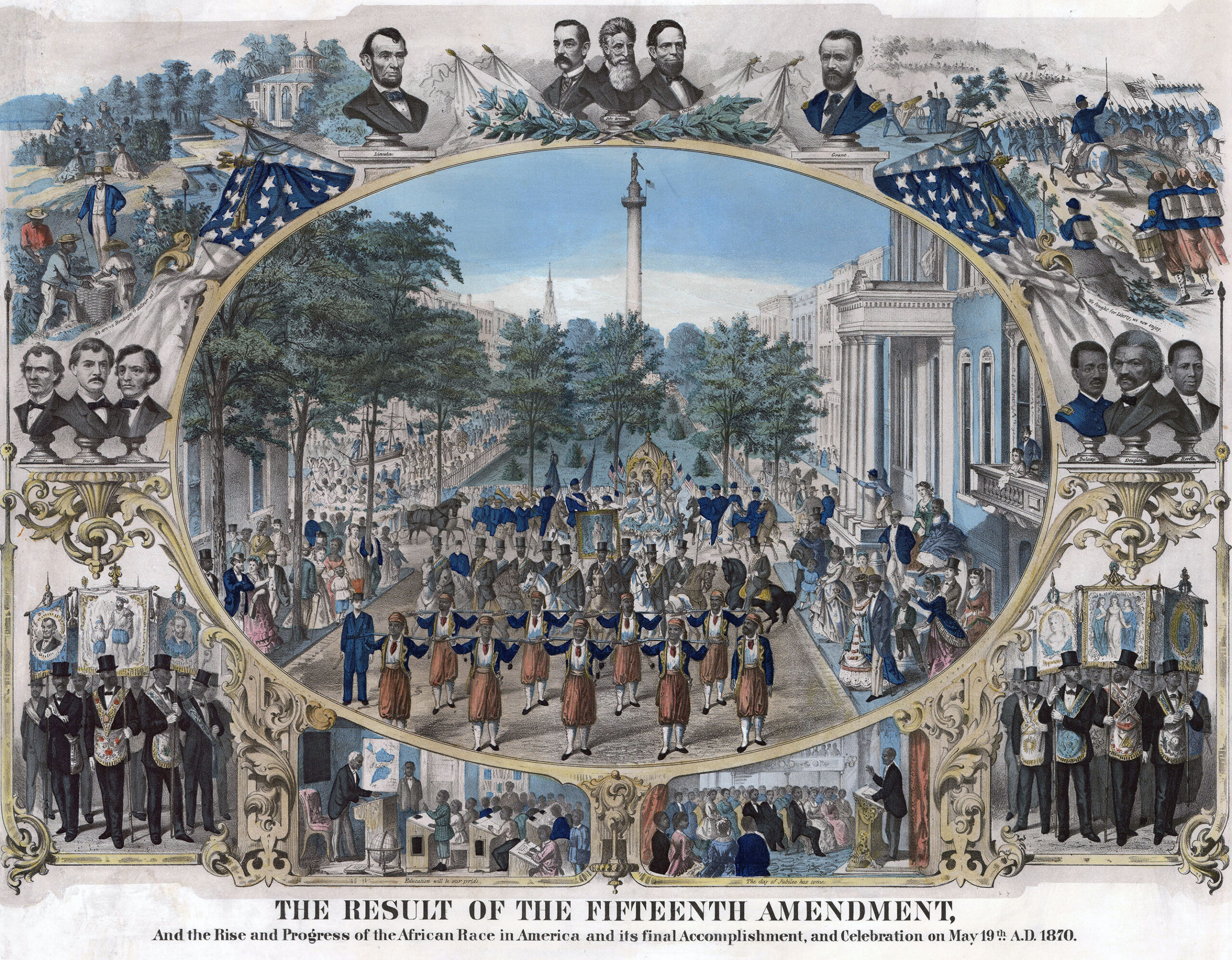

Despite unusual market constraints, the Clements has still been able to acquire exciting new materials, like this lithograph. Featuring the parade held in Baltimore in 1870 celebrating the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, the central image is surrounded by vignettes of African American life and portraits of proponents of emancipation and civil rights.

These questions have been given new salience by the events of the past year, events that have made even clearer how necessary institutions like the Clements Library are for the future of our country. None of the questions that scholars investigate using the library’s materials exist in a vacuum. All bear some relation to our current circumstances, from the terror inspired by the arrival of cholera in the 1830s—the United States’ first experience with a global pandemic—to the long and difficult tradition of state responses to urban protest, from the Boston Massacre to the Haymarket Riot. All of my colleagues at the Clements Library are more committed than ever to helping students and faculty shed light on these connections using the materials on our shelves.

This issue of The Quarto is a bit different than what you’re used to. In many cases, instead of receiving a handsome hard copy in your mailbox, this issue is being delivered to you electronically (although we’ll be glad to create a paper version of this issue if you prefer). And instead of addressing a particular historical topic or a specific set of materials in the collection, this issue will highlight how the Clements has adjusted its work when confronted by the COVID-19 pandemic. My colleagues have developed new ways of reaching out to our supporters—think of the online Clements Bookworm program—and have modified existing practices to suit new realities, as you will see with the discussion of our remote research fellowships.

Another crucial element of the Clements’ work that looks very different now than it did in March is acquisitions. My visit to the New York Antiquarian Book Fair in early March now feels like the last “normal” thing that I did—it was the last time I was in an airport, or in a museum; the last time I rode public transportation or ate in a restaurant; the last time I was indoors with a large group of strangers. The book dealers who are our crucial partners in continuing to build the Clements’ collections have been forced to pivot as well, distributing electronic catalogues and setting up virtual “booths” in online book fairs. And yet, under these altered conditions, we have been able to continue building on the great strengths of the Clements Library’s collections, and have added many exciting new items. I hope that when things are back to whatever will pass for “normal” in the future, you’ll be able to stop by to see some of them in person.

Additions to the James V. Mansfield Papers include portraits of James V. Mansfield (1817-1899) by George Freeman (1789-1868) and Mary Hopkinson Mansfield (1827-1883) by an unknown artist. Hand-colored photographic prints, reverse-mounted on glass, 1857.

We were fortunate in February 2020 to have been very successful at an auction featuring a wide range of materials related to the prominent mid-19th-century American Spiritualist James Valentine Mansfield (1817-1899). The lots we acquired multiplied our previous collection of Mansfield materials several-fold, and established Spiritualism as a great strength of our manuscript collections. We realized, however, that the Book Division was not as strong in the robust print culture of the Spiritualist movement as it should be in order to support research in Spiritualism across the Library. So we set out to address that gap. Among the many fascinating titles that we added, this one stands out: Andrew Jackson Davis’ The Diakka and their Earthly Victims (New York: Progressive Publishing House, 1873). Davis (1826-1910) was one of the most prominent clairvoyants and spiritualists of the 19th century, and he was a prolific author but The Diakka is one of his more obscure books. According to Davis, a “diakka” was the spirit of someone who in life was wicked or unprincipled. After death, the person’s spirit did not change, and these “diakkas” would return from the spirit realm to plague the living. Davis’ book offers a counterpoint to views of Spiritualism that focused on the benign nature of spirits, and will support research in the Mansfield papers and in other collections.

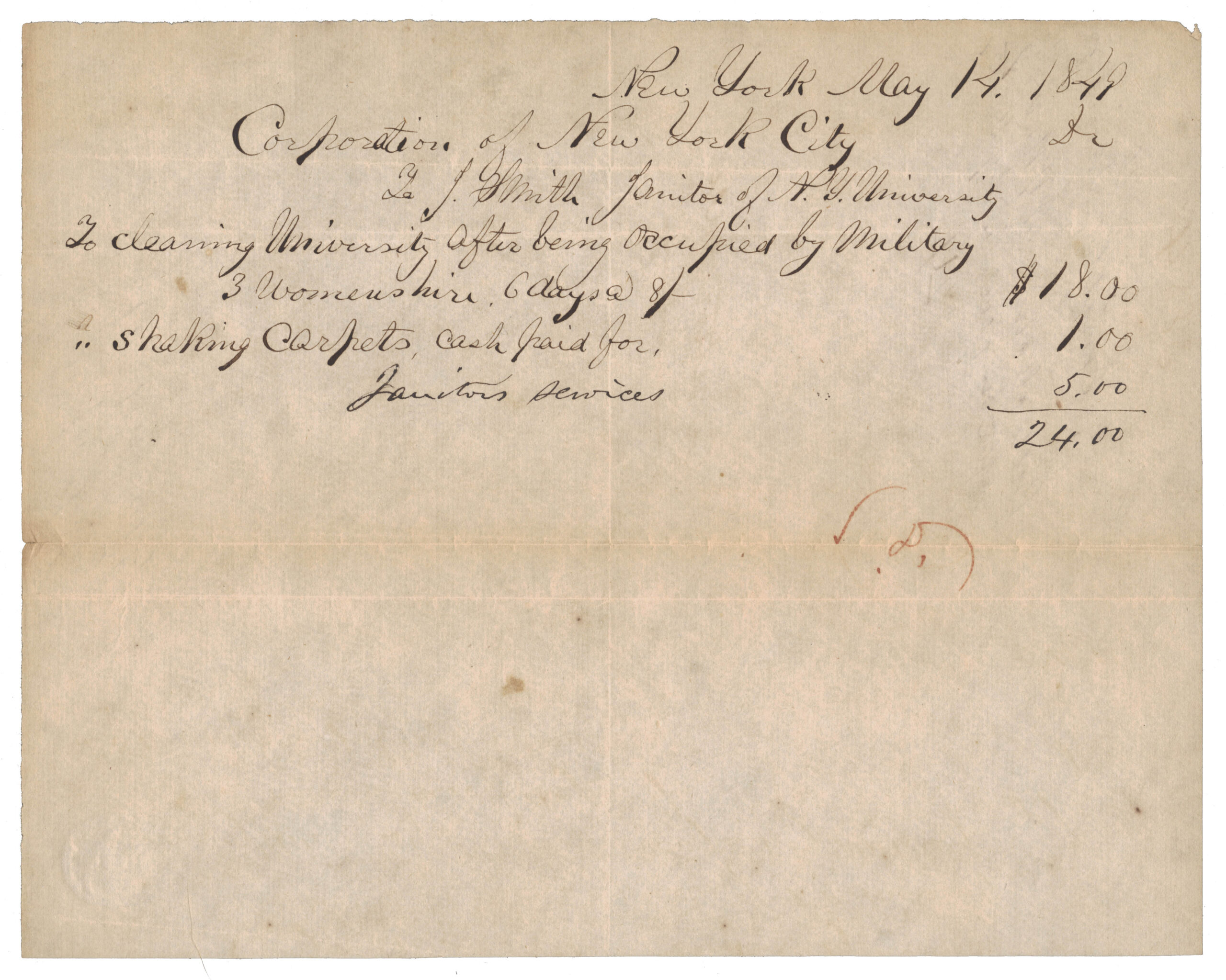

We’ve been able make some marvelous additions to the Manuscript Division this past year, including the Mansfield collections mentioned above. There is one recent acquisition that is far less glamorous, but that to me offers an invaluable insight into the texture of life in America’s past. Many of you will be familiar with the Astor Place Riot, an incident of urban violence that was rooted in a rivalry between two Shakespearean actors. The American Edwin Forrest was the hero of New York City’s working classes, while the British actor William Macready was known for a more refined style that appealed to elite audiences. The actors were appearing in New York in two competing productions of “Macbeth” in May 1849, when a protest outside the Astor Place Theater where Macready was performing turned violent. The police were unable to control the crowds, and the mayor of New York called out the state militia, who fired into the crowd, killing over 20 New Yorkers, making it one of the bloodiest episodes of urban unrest in the 19th-century U.S. The militia were mobilized for several days, and some troops were barracked in a building belonging to New York University. We were able to acquire a bill for janitorial services for cleaning the building after the troops left, submitted to the City of New York for payment. This undistinguished scrap of paper highlights the fact that the stuff of history is not only the events that make headlines in the newspapers, but also the cleaning up afterwards.

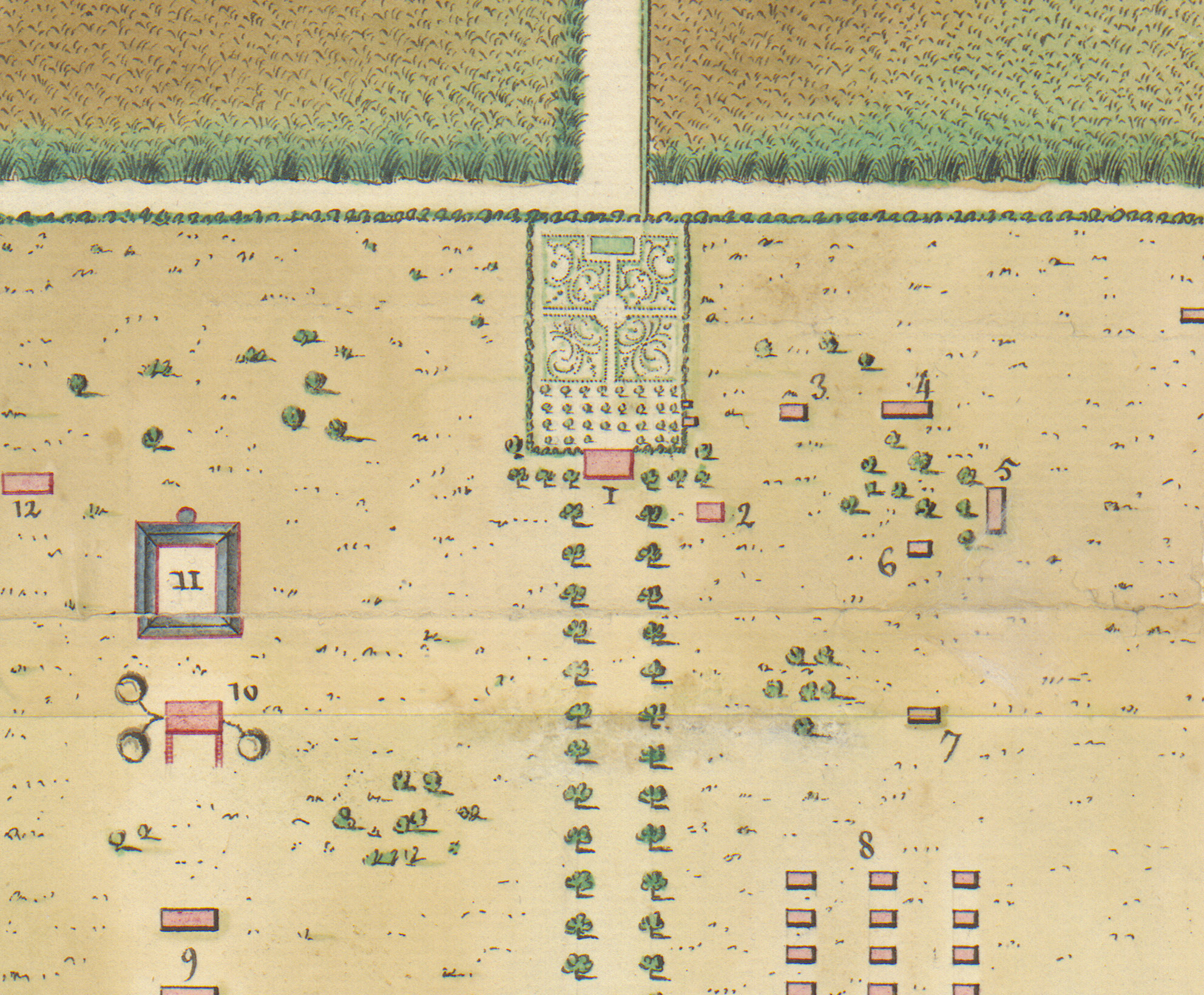

One of the most exciting additions to our map collection is perhaps the smallest. Earlier this fall we were delighted to acquire this quite tiny (3.5 x 6 inches) manuscript map of Cap-Français (now Cap-Haïtien) in Haiti from 1793. This is one of the only surviving contemporary manuscript maps depicting the Great Fire of Cap-Français of 1793 that virtually destroyed the most important French city in the Americas during the early period of the Haitian Revolution. In June 1793, the French governor of Saint-Domingue tried to raise a revolt of the island’s white residents against the republican commissioners who had arrived in Haiti from France to administer the colony. The commissioners responded by promising freedom to any enslaved people who would fight with them. This pen, ink, and watercolor map shows the aftermath of the siege and burning of Cap-Français by the commissioners’ forces, which had reduced 80 percent of the city to ashes. The Clements holds two contemporary prints of the conflagration, as well as several manuscript accounts of the fire.

The Cap-Français map adds to the Clements’ strength in West Indies materials. The brown shaded squares indicate buildings destroyed in the 1793 blaze.

All of you are no doubt familiar with the marvelous Pohrt Collection of Native American Photography at the Clements, made possible by the generosity of the collector Richard Pohrt Jr. as well as Tyler J. and Megan L. Duncan. This collection of over 1000 photographs has been an invaluable addition to the Graphics Division, and photographs from the collection have already been used in a marvelous online exhibit on the Native Midwest and the history of photography. But we did not stop adding to the collection, nor did Richard’s generosity come to an end. With his support, we were able to purchase a set of five spectacular albumen print portraits of leaders from Plains tribes who took part in delegations to Washington, D.C., in the 1850s and ’60s and were photographed there. All of these prints were made by Antonion Zeno Shindler, although some of them were from negatives made by other photographers that he was given permission to reproduce. These delegation images were one of the few weak spots in the original collection, and the addition of these portraits helps highlight an important avenue for Native American political agency. The set includes an image of Tshe-ton-wa-ka-wa-ma-ni, or Little Crow, a Dakota chief who was one of the leaders of the Dakota Uprising in Minnesota in the early 1860s. But the most arresting image of the group, at least to me, is this portrait of Psicha Wakinyan, or Jumping Thunder, a Yankton warrior, made in 1858. These images were part of the first museum exhibition of photography in the United States, an 1869 show at the Smithsonian (following its disastrous 1865 fire) entirely of photographs of Native Americans.

As you will see from this issue, my colleagues at the Clements Library are doing marvelous work under trying conditions to help continue fulfilling the library’s mission of connecting students, faculty, and researchers with original source materials from America’s past. I look forward to seeing you in person at the Clements when the public health situation permits, but in the meantime I am eager to see all of you online under the Virtual Clements banner.

—Paul Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Supplementing the Clements’ collection of satires, these brightly colored cards were intended to entertain through mixing and matching, “by which different combinations of sentences may be made, representing ludicrous utterances of the figures,” according to the patent holder, Walter Strander. Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885) and clergyman Thomas De Witt Talmage (1832-1902) are two of the six figures included in the set.

Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

The plan of Jean-Baptiste de La Porte-Lalanne’s Haiti plantation is the sort of document you have to walk around. Produced in 1753, its features demonstrate the organization and efficiency of 18th-century Atlantic trade, and the conditions of those enslaved at its expense. For teachers and students, the document exemplifies the texts and subtexts that can be found in primary sources and historical research.

Leaning in to view the plan, students might notice the vast uniformity of the sugar fields, the intricacy of the main garden, or the blockish imprecision of the slave quarters. Walking around the document, other names hug the borders of La Porte-Lalanne’s land, signs of the many other plantations that extracted lives and commodities at such scale. Perhaps even touching the paper, one might ponder on the many folds that have disrupted its surface, remnants of its past storage and transportation.

We will never see this plantation, so we must cling to every clue we can find. Yet in 2020, in the midst of a pandemic, we have been distanced further. Our challenges as historians and teachers are not only temporal, but also material. In the absence of in-person interactions, archives and their documents must be met anew.

This was the challenge when arranging a collaborative session between the William L. Clements Library and the undergraduate students of Michigan’s early American history survey course, investigating the documents and history of the Atlantic slave trade. In past years, students met curators and documents in person, discussing and exploring sources in the Clements’ atmospheric reading room. As an instructor, those visits offered the opportunity to take my students somewhere new, outside of the classroom and beyond the realm of PDFs and laptop screens.

With the shift to online learning, these encounters had to be reimagined.

A cardinal rule for researching in person at the Clements Library is never to make marks on historical documents. The online setting allows students to highlight and comment on this passage from the Leyland Company records of a slave trade voyage.

Working with Jayne Ptolemy and Clayton Lewis from the Clements staff, we faced the challenge of bringing students to the Clements over Zoom. This meant factoring in the dynamics and difficulties of the digital environment: the default muting of microphones; the distractions of computers and home life; the dreaded lag and spotty wifi.

Our planning focused on maximizing discussion and minimizing the potentially overwhelming array of classroom technologies. We decided to focus on in-depth preparation and the discussion of just two sources: Jean-Baptiste de La Porte-Lalanne’s plantation and an account book of the Thomas Leyland Company, recording a single slave voyage from Liverpool to Angola, and finally Barbados.

With the variety of technologies on offer, we discovered new opportunities for student engagement and discussion. In advance of the session, students were asked to read through the Thomas Leyland account book. Using Perusall, a digital reading tool, students could discuss the source online, posing questions and responding to each other’s comments.

This meant that we were provided with an array of questions and overlapping interests that might otherwise have been missed with individual preparation. Students asked about the goods transported on the ship, and the various systems of measurement. They conversed about the various professional roles on board, and the fact that seamen could be paid in human beings as well as currency. They expressed their shock at the scale of this journey and its place in the trade as a whole: one of 45 such voyages arranged by Thomas Leyland, and a fraction of over 36,000 in the trade overall. Two hundred sixty-six anonymous lives, in a trade that displaced millions.

Armed with these questions and comments, the Clements curators could present the primary sources in a personalized way for each student. Over Zoom, we could explore students’ reactions to the document, without simply calling upon the most vocal. Digital tools, at least on this occasion, democratized involvement and encouraged broad participation. It was no surprise that Perusall was requested by students in subsequent weeks and will continue to be a valuable tool, even after the return to in-person teaching.

Using Perusall analytics, an online teaching tool, staff can use data—in this case, how long students spent looking at individual pages of the Thomas Leyland Company Account Books—to better understand student engagement with an eye toward improving remote instruction.

This detail from “Plan de l’Habitation de Monsieur de La Port-Lalanne” shows the main plantation house, formal gardens, and a hint of the surrounding sugar cane fields. This small detail shows less than 10% of the overall plan.

Next up was the plan of La Porte-Lalanne’s plantation. This time, without any prior preparation, we directed the students to its place on the Clements website and asked for their first impressions. With significant squinting and zooming in, the plan’s details began to come to light. Given the document’s size, and the restrictions of their computer screens, students were forced to slowly tour the plantation. They had to scroll methodically through its details, perambulating rather than surveying the document as a whole.

With this unique focus, students noticed the smallest features. The lack of trees and shade by the slave quarters, and their distance from almost every other building. The individual sugar canes, indicating the decorative, as well as practical purposes of the plan.

It is impossible to replace in-person encounters with documents, yet digital tools and discussion revealed elements that might otherwise have been missed by the naked eye. And thanks to the expertise of the Clements curators, each component observed by students could be expanded to the broader history of the slave trade and Atlantic history.

While I am undoubtedly excited by the prospect of bringing students back to the Clements Library, it is important that we do not forget the lessons learned in digital teaching. We must continue to consider the circumstances of our students, beyond computer and wifi access. We must work to incorporate ways of learning and participating that do not prioritize certain voices. We must reflect on new ways of viewing and discussing historical documents. We must lean in and take a closer look.

—Alexander Clayton is a Ph.D Student and Graduate Instructor in the University of Michigan History Department. His research and teaching focus on Atlantic History and the History of Science.

Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

COVID-19, with its related State-wide shutdowns, has dramatically increased the need for digitized archival collections. For the Clements Library, reference requests, teaching opportunities, and other services have been limited to what we are able to provide remotely. This demand prompted us to dedicate significantly more staff time to digitizing materials, whether by creating high-resolution digital surrogates for long-term online access or speedier reference snapshots for immediate use. The increased speed with which we have been scanning materials led us to reaffirm and reevaluate our selection process for digitizing archival collections, in order to best serve our teaching activities, remote patrons, and long-term goals. The William L. Clements Library is pleased to report that in these troubling times, its digitization initiatives have amplified and increased, resulting in the scanning of 12 complete archival collections, a modicum of partial collections, and an extraordinary amount of materials for reference purposes.

For the digitization team, the pandemic closure caught us in the midst of a transition. We had just posted the position of digitization technician in January 2020 and completed the interview process a month later. Shortly after Christopher Ridgway accepted the position in early March, the Library closed and everyone shifted to work from home. Fortunately, we had completed the hiring process before a University-wide hiring freeze went into effect, so Chris’ new role with us was secure despite the changing situation. Chris started in April as a remote employee, a real challenge for someone whose work requires hands-on interactions with collections in the Library.

Instead of learning to handle rare items and exploring the Library stacks to become familiar with the collections, Chris spent the summer doing remote training on workflows and technologies, attending webinars and online events related to digitization in cultural institutions, and joining Library staff meetings on Zoom to get to know his new colleagues from a distance. In addition, Chris edited captions for recorded lectures, updated online exhibits, transcribed manuscripts, and designed a logo for our online Bookworm discussion series.

When we were able to re-enter the Library on a limited basis in August, it was wonderful to finally introduce Chris to his workspace and show in person the collections we had been telling him about since April. He quickly picked up the essentials of operating the book scanner and producing scans using our workflow, prepared by his time at home studying the training materials.

Our building re-entry plan called for one-third occupancy, with each staff member in a dedicated workspace using separate equipment. Focusing on key in-person roles such as conservation, cataloging, reference, and digitization, we agreed that our core tasks for the fall semester were to support remote reference and teaching. With relatively few collections fully digitized and online, most of our reference queries and instruction sessions would require new images, so ramping up digitization became a central part of the plan. Cheney J. Schopieray (Curator of Manuscripts) and Emiko Hastings (Curator of Books) both chose to join the first phase of staff returning to the Library in order to restart the digitization program and act as additional technicians during the first phase. We moved the scanners into separate rooms so that each person could have a dedicated space with their own queue of materials to scan.

The Child Toilers of Boston Streets by Emma E. Brown (Boston, 1878) was included in a selection of Clements Library book material on the theme of 19th-century social reforms recently scanned for the HathiTrust Digital Library. A fictional account of the social conditions of child laborers, it ties in with progressive themes in our manuscript collections, and as a more obscure edition, had not yet been made available through HathiTrust.

With no new scans of material produced since December and many researchers who had to postpone their Library visits, we returned to a pent-up demand for digital access. We opted to split the requests into two queues, one for the reference team to answer with quick, low-resolution photographs and the other for the digitization team to fulfill with high-resolution scans suitable for inclusion in an online collection. In this way, we could more speedily address immediate needs, while balancing the long-term goal to sustainably grow our digital collections for enhanced remote access. Staff working from home completed the process by compiling PDFs for users, creating cover sheets and metadata, and responding to the email reference queue.

The high-resolution scanning workflow is a time-consuming process. It involves slower scanning speeds and the careful production of item-level metadata to help organize the images and facilitate searching and retrieval of items in the collection. Once the images and metadata are complete, the University of Michigan Library’s Digital Content & Collections (DCC) department hosts and maintains the collection, a service for which the Clements Library is deeply grateful.

The competing priorities of high-resolution scans versus low-resolution snapshots brings to mind the question of how the Library decides on which archival collections to assign to which workflow. For which collections do we create high-resolution digital surrogates? After all, the time required to digitize one collection is time we are not spending on another. Holding almost 2,800 manuscripts collections, the Clements Library must determine its digitization priorities carefully. When the Library began to scan archival materials in 2019, we selected collections based on a variety of criteria, with a particular eye toward testing the format and display of the digital versions. The selections therefore included examples of single and multi-series collections, oversize manuscripts, and mixtures of bound and loose-leaf items. Other necessary factors included the condition of the materials, the anticipated use of the collection, and a desire to make lesser-known items of importance available in order to increase their use. The German Auxiliaries Muster Rolls and the Samuel Latham Mitchill Papers we knew had immediate audiences waiting for them. The Humphry and Moses Marshall Papers and the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society Papers are multi-series collections with a selection of loose pages, bound items, and oversize materials. We also selected items that might serve as examples of particular subject matter, anticipating future grant proposals to digitize much larger collections pertaining to similar topics. We digitized, for example, the Elizabeth Camp Journals, thinking of potential funding opportunities to scan our individual women’s diaries, and the Henry James Family Correspondence, considering a future project to digitize our Civil War collections.

With the Avenir Foundation Reading Room closed, reference staff re-doubled their efforts to provide quick, reference-quality images to researchers unable to wait for the library to re-open, and not in need of the high-resolution images provided by the scanning team. At the request of a patron, PDF images were created of the Harry A. Simmons sketchbook including this depiction of a ship, composed entirely of mailing stamps. Simmons (b. ca. 1826) served in the Union Navy during the Civil War.

The COVID-19 workplace introduced additional factors for consideration, based on immediate needs associated with reference queries and teaching. The criteria is currently as follows:

• Can the materials be scanned safely in their current state?

• Will digitization reduce wear on fragile materials?

• Do any legal reasons exist preventing the distribution of the digital collection?

• Are the materials organized and have they been cataloged?

• Will the digitized materials serve current reference and fellowship needs?

• Will the digitized materials be used in forthcoming classes or presentations?

• Does the scanning of the collection serve larger digitization goals of the Library?

• Would the scanning of the collection help highlight items related to historically underrepresented persons?

• Does the collection have a broad audience or high public interest?

• How large is the collection and how long will it take to digitize?

• Do we have the funds and resources to digitize the collection?

Over the past nine months, we have created high-resolution scans of the following collections and they are either online or awaiting online deployment:

• Maria M. Churchill Journals, 1845-1848. Daily journal entries providing insights into the emotional and intellectual life of a middle-class woman in the mid-1800s.

• Loftus Cliffe Papers, 1769-1784. Personal letters largely dating from Cliffe’s service in the British Army during the American Revolution.

• Gardner Family Papers, 1776-1789. Documentation of the management of Joseph Gardner’s Jamaica plantation.

• Great Britain Indian Department Collection, 1753-1795. Documents, letters, and other manuscripts relating to interactions between government and military officials, Native Americans, and American residents.

• William Howe Orderly Book, 1776-1778. Copies of orders for a brigade under British Commander-in-Chief Sir William Howe.

• Jacob Aemilius Irving Letter Books, 1809-1816. Letters of a Jamaican sugar planter during the years following the cessation of the British slave trade.

• King Family Papers, 1844-1901. Documenting the business activities of the King brothers, three of whom worked as traders with Russell & Company in China in the mid-19th century, and the subsequent institutionalization of William King.

• Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography, ca. 1855-1940. Approximately 1,420 photographs pertaining to Native American history from the 1850s into the 1920s.

• James Sterling Letter Book, 1761-1765. Outgoing letters of James Sterling, a fur trader at Fort Detroit.

• United Sons of Salem Benevolent Society Minute Book, 1839-1867. Business proceedings of a mid-19th-century African American organization, a hybrid of an insurance agency and charitable operation.

• Weld-Grimké Family Papers: Diaries, 1828-1836. Diaries of abolitionists and women’s rights activists Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Emily Grimké.

• Charles Winstone Letter Book, 1777-1786. Business correspondence of Winstone, attorney general and planter in Dominica during and after the American Revolution.

The pandemic has allowed the Clements Library to accumulate a backlog of digitized collections waiting to go online. The Great Britain Indian Department Collection is an important body of documents, letters, and manuscripts relating to interactions between government and military officials, Native Americans, and American residents from 1753 to 1795. This manuscript documentation of a council meeting, May 18, 1785, contains eloquent speeches by Lenape/Delaware Chief Captain Wolf and Shawanese Chief Kekewepelethy (“Captain Johnny”) demanding that the Americans prevent Virginians from encroaching on lands west of the Ohio River in accordance with treaties.

While the pandemic temporarily disrupted our digitization process, it also pushed us to increase the capacity and efficiency of our scanning program. Previously, we had relied upon physical access in the reading room as the primary means by which researchers could interact with the collections, with digitization something to be done in addition as time and other projects allowed. With in-person access now strictly limited, we have become more flexible and creative in finding ways to make materials available to researchers across the world, whether through quick reference snapshots, high-resolution scans, or even digitizing old microfilm reels. Many of these efforts will benefit researchers long after the pandemic is over, as we continue to improve our online presence and make collections more widely available outside the confines of the Library building.

—Emiko Hastings

Curator of Books and Digital Projects Librarian

—Cheney J. Schopieray

Curator of Manuscripts

Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

Forrester (“Woody”) Lee of New Haven, Connecticut, spent an extraordinary amount of time carefully transcribing the phonetic spelling of the United Sons of Salem Benevolent Society Minute Book and helping make this important volume more accessible to readers.

While providing collection scans online is a tremendous help to researchers who are unable to visit the Clements Library either due to the pandemic or to time or financial constraints, providing true searchability of digitized material is the gold standard.

In March 2020, the Clements Library began experimenting with a group transcription process. FromThePage, a software platform, provided the interface for collaborative transcription of online documents. The Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society Papers, one of our richest collections related to the Underground Railroad, provided the source material.

Clements staff, recently exiled from in-person contact with collections, seized the opportunity to interact with these papers remotely and at the same time provide an invaluable service to our patrons. Each page of the collection was read, puzzled over, and ultimately transcribed. Staff checked each other’s work, asked for help with difficult words, and did online research to reveal the identities of difficult-to-decipher names of historic figures. The project provided a much-needed distraction and escape from the dislocation, anxiety, and uncertainty in the early days of the pandemic.

After the initial phase of trial-by-staff, the transcription project was opened up to volunteers. Individuals and groups of persons have contributed to the transcription project. The Sarah Caswell Angell Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) transcribed the Revolutionary War papers of Colonel Jonathan Chase, of the 13th and 15th Regiments of the New Hampshire Militia. This semester, Andrea Smeeton’s 7th grade students at East Prairie School in Skokie, Illinois, successfully transcribed selections from the letters of 19th-century writer and activist Lydia Maria Child. Many highly dedicated individuals have contributed to the completion of transcriptions for the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society Papers, United Sons of Salem Benevolent Society Minute Book, Louise Gilman Papers, African American History Collection, Samuel Latham Mitchill Papers, and James Sterling Letter Book. Some of these transcriptions are already live and available to researchers and others are awaiting final review before releasing them to the world.

Our partners in U-M Library Digital Content & Collections have merged the transcriptions with the existing digital collections to make them fully text searchable. Now, a researcher utilizing one of our transcribed collections and looking for a specific mention of a particular subject—fugitive, freedmen— receives immediate search results with the corresponding scanned pages of the original document. Previously, the search could be undertaken only by laboriously scrutinizing each document for the appearance of the word in question.

The Clements Library plans to continue to provide new collections online via FromThePage for those who enjoy the challenge of puzzling out a variety of handwriting styles and taking a closer look at the content of these remarkable resources.

—Terese Austin

Head of Reader Services

The papers of Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880), a writer, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist, were among the digitized collections recently completed. In this letter from Mrs. Child to her friend Anna Loring, July 1, 1871, volunteers transcribed:

“You ask what I think concerning the political enfranchisement of women. I have for many years been decidedly in favor of it. I dont feel interested in it as a right to be claimed, but as the most efficient means of helping the human race onward to the highest and best state of society. A really harmonious structure of society requires complete, unqualified companionship between the sexes. Homes will be nobler, and capable of higher and fuller happiness, when the mothers, wives, and sisters, in families, have an understanding sympathy in the investigations of science, the designs of artists, the experiments of the agriculturist, the enterprises of the merchant, the inventions of the machinist, the labors of the mechanic, the theories of politicians, and the guidance of statesmen. And in order to have an understanding sympathy with these things, they must have part and portion in the performance of them.”

Taking Fellowships Digital

In 2019 the Clements introduced a new Digital Fellowship, where we scan a collection identified by our fellow for them to consult from their home institution. Imagined well before the public health challenges presented to us by the coronavirus, it now stands as a model for how we can still work to support researchers even if they can’t travel to our reading room. Our inaugural Digital Fellow, Lauren Davis, a doctoral candidate at the University of Rochester’s History Department, talked to us about her project and the power of remote historical research. The transcript of our conversation appears below, condensed and edited slightly.

—Jayne Ptolemy

Assistant Curator of Manuscripts

Jayne Ptolemy (JP): Tell us about your project and the types of sources you use to uncover your story.

Lauren Davis (LD): My dissertation is entitled “Beyond Institutions: Mental Disorders and the Family in New York, 1830-1900,” and it explores how families cared for relatives with mental illness in the 19th century. I found that nuclear and extended families were taking part in a lot of home caregiving, were helping to make healthcare decisions, and were negotiating patients’ treatment with physicians when they felt like institutionalization was necessary. Despite families directing every stage of mental health treatment, the history of mental health is dominated by a focus on institutions and prominent physicians. My dissertation restores families to the narrative of mental health care, establishes a lay perspective on diagnosis and treatment of mental illness, and contributes to the history of gender at the intersection of medicine. It challenges the existing interpretations of American asylums as the first and last resort for mental health care.

There’s a pretty wide variety in the sources that I’m using. I use a lot of family correspondence and diaries, which give me the most qualitative information about a particular caregiving situation. Families are seeking cures for their relatives, and if a cure or improvement doesn’t seem like it’s possible, then they want to provide the best long-range care that they can. Sometimes they choose an institution, but a lot of times they rely on home care. This isn’t necessarily a situation where someone is institutionalized and then stays there for the rest of their lives. A lot of times they’re institutionalized for a period, and then after a few years they determine that they’ve received the most benefit that can be achieved and they will be pulled back out of the institution. They return home and live with their family supporting their care.

(JP): Which Clements collection are you working with, and why did you select it?

(LD): I’m working with the King Family Papers. I’m interested in the declining mental health of William King and his brothers’ efforts to care for him. The King family correspondence includes discussions of his brothers’ direct interventions, consultations with physicians, and their commitment of William to a private insane asylum. I’m interested in seeing why the brothers decided to commit William, how they selected an institution, if they thought he was curable and if that changed over time, and how they negotiated his care with physicians when they thought it was appropriate to consult with them.

This July 31, 1870, letter details Edward King’s struggles to contend with his brother William’s declining mental health. The handwriting itself seems to reveal the agonizing emotional turmoil and the inadequacy of words to describe a family’s calamity.

(JP): How is working from digital surrogates different from researching in-person at a library? What challenges and benefits does it yield?

(LD): I thought about this in two different ways. First, when I’m researching in person, I’m able to browse across multiple collections, and I can see what might be relevant to my project. This is hard to replace without having digital options available for all the same materials. When I have digital images for a whole collection, though, it is an advantage for my research. When I’m working with family papers, the narrative threads run through many of the family letters. The dynamics of relationships within every family are unique, and the outlook a person has on caregiving is not isolated from the rest of these relationships. Having the time to explore the context of surrounding letters in a collection is vital for understanding this.

The other side that I thought about is in terms of reading the text. With high quality images, researchers now can manipulate the image by zooming in or adjusting the contrast. Those are things that make the text clearer in ways that’s not possible with a physical manuscript. It’s also a lot easier to ask about a particularly tricky word if you have a digital image you’re able to share with a colleague. My friends and I send screenshots, asking each other, “What do you think this word is?”

(JP): From a researcher’s perspective, what is the value of digital fellowships that don’t have a residency requirement, even without a global pandemic?

(LD): The pandemic definitely has changed the perspective and outlook on digital fellowships, but one of the largest benefits at any point is being able to process the collection at home, on my own timeline. A visit to an archive provides advantages, but it also requires resources to allow for travel and multiple days spent in a reading room. Any time I travel to an archive I try to be as efficient as I can, so I’m using my time to gather the most helpful information as quickly as possible. That means making a lot of judgments on what’s the most relevant and important. Sometimes these decisions are clear, but sometimes they’re more ambiguous, or new details alter my conclusions. In one case, after I read a few dozen letters, I discovered that a family friend often interacted with an institutionalized relative. By having images of that collection I was able to go back and consult the material again to follow the different paths and clarify points of ambiguity. Being able to consult the images as your research evolves is very helpful.

Sometimes it’s just one line about one person that helps piece together the narrative, and it may not come up until ten years after the specific time period of their care. With family letters, it’s key to have the surrounding context. It takes a long time to process them, so being able to do that digitally is a big benefit for me.

(JP): What main lessons has researching in the age of COVID taught you?

(LD): I think the biggest thing is having to be flexible to navigate the changes the pandemic has brought. I had plans to visit several archives in the spring of 2020. All the facilities closed to visitors, so that’s been impossible. I have had to adjust, use what I have, and be creative about what I’m able to access. Before the pandemic I’d actually never worked with microfilm. I had always had better alternatives, either using the manuscripts or better quality digital images. I had a particular set of volumes, where the reading room was closed and I couldn’t visit that archive. They had microfilm they could send via Interlibrary Loan, so I was able to process it at my university’s library and work my way through the sixteen volume series. It was a new experience for me, but it worked! Flexibility is the biggest thing, having to be creative and rethinking plans about how to get as much information as I can.

Much like Lauren, we’ve found that this challenging season has taught us the resounding power of being flexible and harnessing the resources at our disposal. Zoom conversations with fellows, high resolution scans, reference photos taken with cell phones—in ways big and small, we have been using technology and digital surrogates to support innovative research like Lauren’s from a distance. Until we’re once again able to crowd around the tea table with all our fellows to discuss their archival finds of the day, we’ll continue to look to the power of technology to keep us connected and moving forward.

Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

The concept that the human brain processes information differently when all our senses are engaged is fundamental to the mission of the Clements Library. Vintage leather bound books have a certain smell. Turning pages of old hand-made paper can make a crisp sound or a soft murmur. Books can be thick, thin, light or heavy. Historical documents have weight, texture, smells and sound that we respond to with more than our eyes alone. When in direct contact with rare materials, all of these elements stimulate our senses for a deep-dive immersion into the past that is impossible to replicate digitally. This has much to do with why we believe that the experience of working directly with original primary source materials brings out the best in scholars of history.

When studying historical photographs, there is a growing awareness that considerations of physicality contribute to meaning. It is easy to become so enraptured with the image itself that we can forget that it comes to us on a physical platform. A photo may be on paper, glass, metal, wood, ivory, perhaps in a protective case like a daguerreotype, or in a wooden frame for the wall. There is often a brittleness that commands cautious handling, and physical scale that can be surprising. Additionally, photographs are responsive to lighting conditions. The uniformity of computer screens can hide the fact that that photos can look different at different times of day, that daguerreotypes are highly reflective, but also carry deep contrasts.

The Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography contains a wide variety of physical formats: card-mounted paper photographic prints, unmounted glossy photos, small cartes de visite, large framed panoramic views, tintypes, stereoviews, and photo albums. Some of these photos invite intimate and up-close viewing, others broadcast from across the room.

Experiencing all of this in a rich sensory experience is what we had in mind when we posted internships funded by the Upton Family Foundation in the fall of 2018. The plan was to hire talented students to work directly with the Pohrt Collection materials to produce a traveling poster exhibit. We were delighted to bring on board Dr. Andrew Rutledge, whose qualifications exceeded our expectations. Andrew considered as a theme the dynamic but often troubling role that photography played in Native American history. In the 19th century, there was plenty of hostility between indigenous populations and the incoming settlers, soldiers, and photographers. However the Pohrt Collection also shows us hundreds of images that could not have been taken without cooperation from the Native American subjects. To what extent did these dynamics shape the Pohrt Collection materials? Are there 19th-century examples of Native Americans using photography for themselves?

Andrew researched the material, immersed himself in the history, and proposed a detailed exploration focused on the Great Lakes region and the Anishinaabe people. However, Andrew’s destiny lay elsewhere and he took an irresistible full-time position at the Bentley Library across town where he continues to do exemplary work for the university.

This set-back was also an opportunity to take stock of where we were and to re-set. We reposted the internship position and quickly found ourselves in a pleasant dilemma stemming from a remarkably talented pool of applicants. Fortunately, financial support allowed us to hire two interns, Lindsey Willow Smith and Veronica Cook Williamson.

Lindsey Willow Smith is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, majoring in History with a minor in Museum Studies. She is active within the Indigenous community on campus, serving as Chairman for the Native American Student Association. Lindsey is also researching the use of census data in describing Native populations with Arland Thornton and Linda Young-DeMarco at the Institute for Social Research at U-M.

Lindsey Willow Smith is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, majoring in History with a minor in Museum Studies. She is active within the Indigenous community on campus, serving as Chairman for the Native American Student Association. Lindsey is also researching the use of census data in describing Native populations with Arland Thornton and Linda Young-DeMarco at the Institute for Social Research at U-M.

Veronica Cook Williamson is a graduate student in the department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and in the program of Museum Studies. Her primary research focuses on racial(izing) processes in media and other cultural representations of newcomers in Germany. She graduated with a BA in German Cultural Studies and Film and Media Studies from Dartmouth College in 2017. She has Irish, British, and Choctaw ancestry and is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation — chickasha saya.

Veronica Cook Williamson is a graduate student in the department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and in the program of Museum Studies. Her primary research focuses on racial(izing) processes in media and other cultural representations of newcomers in Germany. She graduated with a BA in German Cultural Studies and Film and Media Studies from Dartmouth College in 2017. She has Irish, British, and Choctaw ancestry and is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation — chickasha saya.

The new team of Lindsey, Veronica, Graphics Cataloger Jakob Dopp, Reference Librarian Louis Miller, and myself met in the Library on March 3, full of ambition and anticipation. We did not know that this would be our only in-person meeting. On March 11 the University of Michigan closed its campus and remote work began, for what we thought would be a few weeks or months.

As the new reality took hold, it became apparent that the demand for online access and support for remote teaching superseded any of our plans for an “in real life” traveling exhibit. Should the internships continue? Fortunately, Jakob had completed item-level cataloging of the Pohrt Collection and Andrew, Jakob, and Louie had uploaded an extensive and detailed online finding aid for the collection. We had scans of most of the materials, enough that we could shift the project to the creation of an online exhibit. The internships could continue, and had the potential to create a timely and supportive resource.

We met regularly (on Zoom of course). Lindsey and Veronica proposed a rewrite that examined the issues of colonialism, Native sovereignty, self-identification, and cultural appropriation in the photographic representations—ideas that were challenging, but well-grounded in history and frequently downplayed.

The editing of the online exhibit, “No, Not Even for a Picture,” required the removal of some outstanding and important images. They include those pictured here and below. “Taking the Census at Standing Rock, Dakota.” D. F. Barry, 1885, 20 x 25 cm.

Detail, “Taking the Census at Standing Rock, Dakota.” F. Barry, 1885.

The man with the cane standing by the desk of the census enumerator is likely Lakota Chief Gall, one of Sitting Bull’s most trusted lieutenants at Little Big Horn, later a converted Christian who mediated assimilation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) recorded the census annually during this time.

“L. Troop Mon. [S]Couts” O.S. Goff, 1890, 20 x 25 cm.

Nine unidentified Crow Indian scouts of L. Troop, 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment, pose with their troop flag and a large American flag, possibly taken at Fort Maginnis, Montana. Many of the Native Americans enlisted in the United States military services were not citizens of the United States. Until the Indian Citizen Act of 1924, becoming a U.S. citizen often required formally leaving your tribe.

The themes and resources of the project were refined with invaluable input from Eric Hemenway, Director of Repatriation, Archives and Records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and Arland Thornton, Professor of Sociology, Population Studies, and Survey Research at the University of Michigan, as well as from Richard Pohrt.

None of this work came easily. We had disagreements about interpretation and what was appropriate. The early versions had enough content for three exhibits. We were all sick of the isolation. Lindsey later commented that “as a Chippewa woman, the balancing of my views and experiences with those of the Clements was a chore.” She stated that “the inequity of emotional investment” was both wearisome and energizing. But as Veronica stated, “the photographs carried this project forward; they were the life force fighting back against video call malaise and quarantine fatigue.”

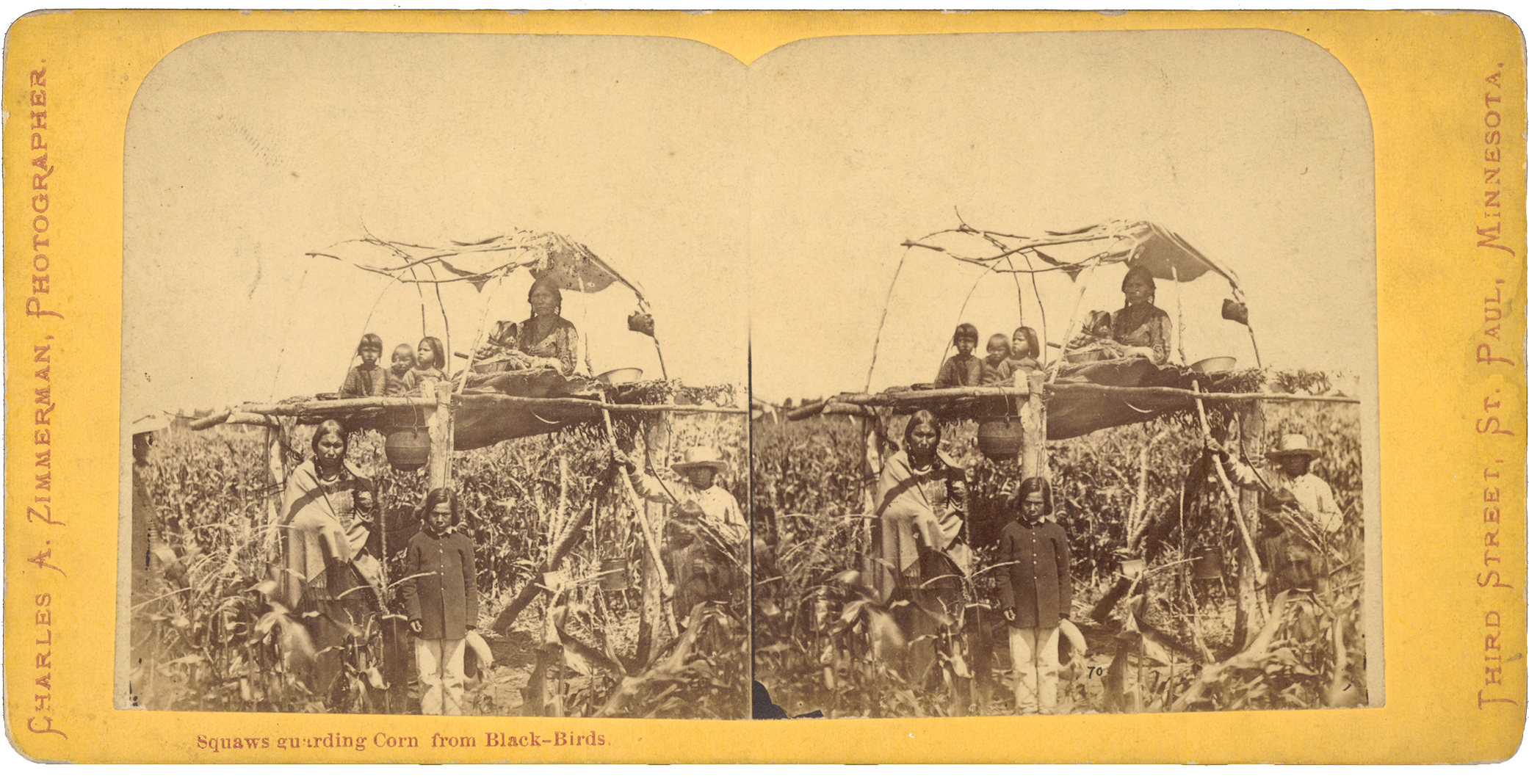

“Squaws Guarding Corn from Black-Birds” Adrian Ebell, ca. 1872, 8.5 x 18 cm.

Possibly taken on the very morning that the 1862 Dakota War uprisings began, this stereograph depicts an unidentified Dakota woman and four children sitting on an elevated platform standing watch over crops. This 1872 print from the 1862 negative would have been produced sometime after Charles Zimmerman took over the Whitney Gallery.

Later in the summer, University policies allowed access to the Clements building and the collection. After many months of remote work, Lindsey and Veronica had their first opportunity to view the actual photos at the Library. The power of this materiality is discussed eloquently in Lindsey and Veronica’s blog post for the Clements Library Chronicles.

I am very proud of this project. I am particularly proud that issues were discussed and decided within the team, that the curation and interpretive concept were led by Lindsey and Veronica, and that their voices came to the fore in the final product. In spite of being thrust together as strangers forced to be partners, employed by an institution that neither knew, using unfamiliar work and communication methods, with a pandemic just outside the door, Lindsey and Veronica’s talents and visions meshed. They create a unified, thoughtful, and challenging look at photography and Native American history that will have lasting value as well as serving the immediate need to support remote education. The online exhibit, “No, Not Even For a Picture,” is a remarkable accomplishment under any circumstances. Given what the project team faced, it is all the more so. It is only one of many projects that are waiting to emerge from the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Material

Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

As I write this article 2020 has come to a close. This is likely a year that will be studied by many future generations as they try to untangle fact from fiction, trace cause and effect, and link the past to the present. This year we have also heard many negative critiques about various aspects of history being “rewritten.” I’ve been thinking a lot about this, because as Director of Development I have been raising money to expand our fellowship program. Our fellows come to the Clements Library to study the primary sources housed within its walls. They come to ask questions and take a critical look at American history. How might their work change our understanding of a well-known narrative?

If you watched our December Discover Series on Benedict Arnold, you heard Curator of Manuscripts Cheney Schopieray discuss how historians have used the Clinton Papers to uncover details about Benedict Arnold’s treason. If we had only relied on previous tellings of Arnold’s activities, we might still believe 19th-century accounts of his childhood. In books like The Life and Treason of Benedict Arnold (Boston, 1835), historian Jared Sparks used unsubstantiated tales to justify writing about Arnold’s pharmacist apprenticeship and his use of the broken glass vials: “. . . he would scatter in the path broken pieces of glass taken from the crates, by which the children would cut their feet in coming from the school.” Benedict Arnold had become a mythical, evil character and it wasn’t until William L. Clements purchased Henry Clinton’s papers during the 20th century that serious scholarship could be undertaken respecting his treasonous interactions with the British. In this sense, yes, we do need to rewrite history. Places like the Clements Library acquire and make available the primary sources that allow historians to carefully research and analyze the actions of even well-known figures in order to understand and even update the impact they have had on both the past and the present.

Another movement around the country this year has been the acknowledgement that unjust policies and institutionalized racism continue to affect the quality of life for many Americans. In June we released an anti-racism statement at the Clements provoking powerful and thoughtful discussions before and after its release.

These conversations have led me to think about and talk about my own family history. I have seen some writers speculate that anti-racist policies also seek to “rewrite history.” Using a segment of my ancestry, I hope to explain what it means to be “anti-racist” or “inclusive” in writing about and discussing our nation’s record. The facts, dates, and people that countless school children have memorized over the years have not changed. They still exist. What we can choose to do now is to fill in the gaps with the people, experiences, and events that were not previously mentioned.

For example, the fact that an Army officer named Richard Pratt founded the first U.S. Training and Industrial School in 1879 at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, has not changed. At the time, Pratt thought that he was doing something good. “A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one,” Pratt said. “In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Many episodes in history have typically been told by people in positions of power, like Pratt.

The Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School operated from June 30, 1893 to June 6, 1934 with an average enrollment of 300 students per year.

So, how can we tell this account better? We can discuss that 150 schools opened all over the country and over the course of 125 years 180,000 children were taken from their families. We can acknowledge the experiences of people like my great-grandmother, Elizabeth Shay-Kaw, who was sent to the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School and endured the harsh lessons of assimilation. We can analyze the effects of these schools on the families and tribes.

It is not just scholars who shape how we write about and study American history. You can help by making a gift to the Clements Library to continue the critical work that is being done.

I hope you’ll also agree that historical narrative should include both Richard Pratt and Elizabeth Shay-Kaw. We can’t go back to change history and right the wrongs that happened, but we can choose to be part of a more just and inclusive society where we learn and tell stories about all the people who have walked this land we now call America.

—Angela Oonk

Director of Development

Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors News

At the October 2020 meeting a resolution was passed naming Peter Heydon Honorary Member and Chair Emeritus.

In March 2020 Thomas Kingsley passed away. He served on the board for 30 years before retiring in 2011 and being named an Honorary Member. His wife Sally has made a gift in his memory for acquisitions.

Exhibitions

“No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography – Online Exhibition at clements.umich.edu/pohrt

This exhibition investigates the complex balance between violation of privacy and the quest for self-identification felt by Native peoples during the early era of photography. Photographic styles and practices are examined that recorded the people, activities, stereotypes, and myths of this important time, focusing on the Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region and beyond.

Framing Identity: Representations of Empowerment and Resilience in the Black Experience – Online Exhibition at clements.umich.edu/framing-identity

Drawing inspiration from Frederick Douglass’ views on picture-making and representation, this exhibition examines how 19th- and 20th- century African American artists and intellectuals expressed identity through portraiture, photography, and literature. A curatorial project developed by 2019-21 Joyce Bonk Fellow Samantha Hill, images were selected from published works and original photographs at the Clements, particularly the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography.

Publications

Mary Pedley, Map Division, is pleased to announce the release of Cartography in the European Enlightenment (Chicago, 2020), Volume Four of The History of Cartography series. Edited by Pedley and Matthew H. Edney, this comprehensive reference encyclopedia focuses on the art, craft, science, and techniques of maps and mapping between 1650 and 1800. Volume 4 includes 479 entries containing 751,995 words and 954 full color illustrations, with about 4,988 references, spread over 1,651 pages—supported by a 100+ page index—written by 207 contributors from 26 countries.

The History of Cartography reference books are produced by the History of Cartography Project, Department of Geography, University of Wisconsin-Madison. Established in 1981, the Project is a research, editorial, and publishing venture that treats maps as cultural artifacts created from prehistory through the 20th century.

To learn more about the project and the other volumes of the History of Cartography series go to geography.wisc.edu/histcart.

Matthew Edney and Mary Pedley flank the completed manuscript of Volume Four of The History of Cartography in the spring of 2018, shortly before its delivery to the University of Chicago Press, where it underwent 18 months of copy-editing, indexing, and layout, prior to publication and printing. It was released in April 2020.

Virtual Programming

In March 2020, the Clements Library launched a webinar series in which panelists and featured guests discuss history topics. Join us continuing monthly in 2021, and access recordings of past episodes at clements.umich.edu/bookworm.

Our popular Discover Series has also gone virtual. In 2020, Clements staff presented fabulous sessions on the history of photography, women’s history in the archives, and the treasonous correspondence of Benedict Arnold. Access the recordings at clements.umich.edu/virtual-discover-series.

Staff News

Former Clements Library staff member Louis Miller has accepted a position as Cartography Reference and Teaching Librarian at the Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education at the University of Southern Maine in Portland. Louie was a knowledgeable, diligent, creative, and enthusiastic member of the Graphics Division and Reference teams at the Clements. He was always eager to share his many talents and his cheerful energy—he is and will be greatly missed! We wish him well on his new adventure.

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Mark S. Schlissel, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Candace Dufek, William G. Earle, Charles R. Eisendrath, Paul Ganson, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Martha S. Jones, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, Thomas C. Liebman, Richard C. Marsh, Janet Mueller, Drew Peslar,

Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Martha R. Seger, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Peter Heydon, Chair Emeritus

Philip P. Mason, Joanna Schoff.

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Tracy Payovich, Designer, [email protected]

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Sarah Hubbard, Okemos; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Mark S. Schlissel, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.