No. 52 (Winter/Spring 2020)

The Best of the West

For nearly a century the Clements Library has been mounting exhibitions and issuing publications based on our collections. In the 1920s and ’30s, under first director Randolph G. Adams, we concentrated on publicizing our greatest area of collecting strength, manuscripts relating to the era of the American Revolution. Our scope gradually expanded to other concentrations in our holdings, with 1940s and ’50s exhibits and bulletins on Michigan history, religion in early America, Canadiana, Ohio rarities, maritime history, colonial Mexico, and early American law. During John C. Dann’s three decades as director we highlighted a broad array of subjects and material – Native Americans, women, culinary history, African American history, travel, caricature, Detroit’s tercentenary – while continuing to showcase our printed and manuscript American Revolution treasures. In recent years we’ve offered visitors and readers a varied menu of topics, from the War of 1812 to education, sports to “friends in fur and feathers,” the Civil War to the West Indies. The result, as our Clements Library predecessors and current staff have hoped, has been that friends and supporters of the Library have been able to sample the extraordinary range of primary sources available here on American history from 1492 to the end of the 19th century.

One major area of Americana collecting that we may have slighted in all this activity, despite it being an area of considerable strength here, has been western Americana. Looking back through my files on our exhibitions, issues of The Quarto, and our Occasional Bulletin series, I come away with the impression that we’ve neglected the trans-Mississippi West in telling the world about the Library. In 1946 we published Fifty Texas Rarities, a catalog of an exhibition of books and pamphlets from the remarkable collection of Everett D. Graff of Chicago, no doubt in an attempt to persuade Mr. Graff to donate his library to the Clements (the Graff Collection, alas, went to his hometown Newberry Library). Twenty years later young Clements staffers Albert T. Klyberg and Nathaniel N. Shipton created Frontier Pages and Pistols, an exhibit of Clements books and hand guns on “the beckoning West,” and published the results as Occasional Bulletin 72. Perhaps motivated by that initiative, in 1967 longtime Library supporter James Shearer II donated his western Americana collection to the Clements, and we showcased selections from that gift as a Beyond the Mississippi exhibit and accompanying catalog. Other than those projects, however, we seem to have been silent for the most part on our western holdings, despite ongoing and impressive acquisitions in all of our collecting divisions.

Thomas Moran (1827-1926) joined the Hayden survey expedition to the West in 1871 and produced iconic views of the dramatic landscapes they encountered, such as this lithograph of The Grand Cañon of the Colorado River, drawing Americans’ attention and imagination westward.

In the early days of 2019, when the Library’s senior managers group met to discuss our exhibitions schedule, my colleagues suggested that I organize a valedictory show before my retirement at the end of the year. Casting about for a good subject, I decided to concentrate on western Americana and to dedicate the exhibit to William S. Reese, who passed away in June 2018. I regard Bill – antiquarian book dealer, scholar, generous supporter of the Clements and other American history research institutions – as the outstanding Americanist of our time, and I knew I could use his 2017 book The Best of the West: 250 Classic Works of Western Americana as the basis for a Clements exhibit. I went through The Best of the West for information and inspiration, and was delighted to find that the Clements owns 90% of the pre-1900 titles in it. Selecting the 45 books and pamphlets our 16 exhibit cases could hold was a challenge, but one I embraced as considerably more enjoyable for a last year at the helm than the concentration on personnel, budgets, meetings, and institutional planning that otherwise fills my days in the office.

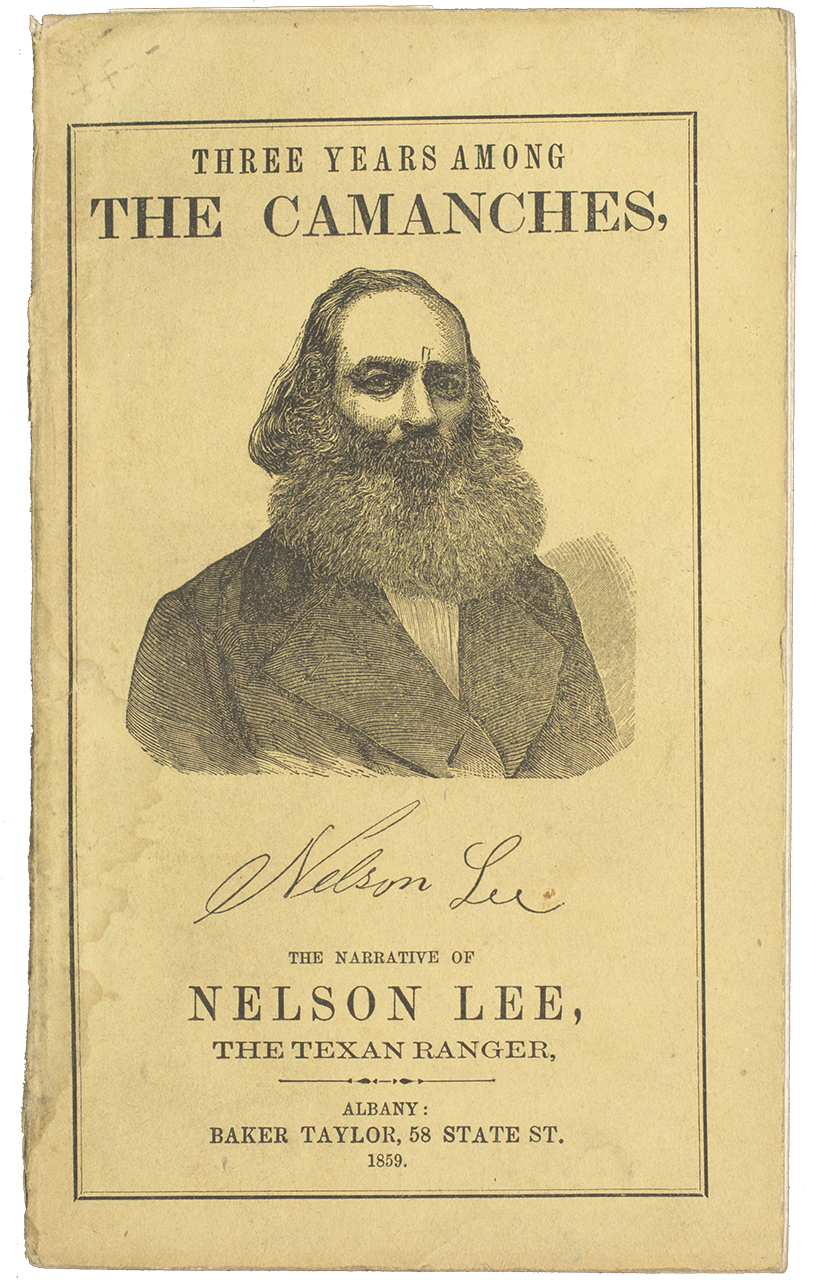

Visitors to The Best of the West, which will run through April 2020, will appreciate that “the west” has evolved as a geographic descriptor over the years. At the same time that Spanish authors like Miguel Benegas, Francisco Palóu, and Josef Espinosa y Tello were writing about Spain’s settlements in California and Mexico, English and American observers were describing the Mississippi River Valley as the farthest extent of settlement and exploration from the East Coast. The exhibit includes Philip Pittman’s 1770 Present State of the European Settlements on the Mississippi, Zadock Cramer’s 1802 Ohio and Mississippi Navigator, and the 1814 first edition of the Lewis and Clark report on their expedition to the West Coast and back. The cases for the middle decades of the 19th century feature Hall J. Kelley, John B. Wyeth, Eugène Duflot du Mofras, and Henry James Warre on Oregon, the George Catlin and McKenney and Hall portfolios of Native American portraits, and rare overland narratives by James O. Pattie, Zenas Leonard, Joel Palmer, and Riley Root. The 1851 George W. Kendall and Carl Nebel folio on the Mexican War and Henry Lewis’ 1855-58 Das Illustrirte Mississippithal display in impressive fashion the chromolithographed images through which many Americans first viewed the West. After 1850 the focus of the exhibit shifts to mining, outlaws, encounters with Native Americans, and the settlement of new areas from Arizona to Idaho, with Nelson Lee’s Three Years Among the Camanches (1859), C. M. Clark’s A Trip to Pike’s Peak and Notes by the Way (1861), John L. Campbell’s Idaho: Six Months in the New Gold Diggings (1864), Thomas J. Dimsdale’s The Vigilantes of Montana (1866), and Thomas F. Dawson & F. J. V. Skiff’s The Ute War (1879) among the titles on display. Viewers will note that a majority of the items in the exhibit came to the Clements during the 1953-1977 directorship of Howard H. Peckham, and I am most appreciative of Howard’s acquisition of so many high points in western Americana that have subsequently soared to prices that would challenge our acquisitions endowments if we attempted to buy them today.

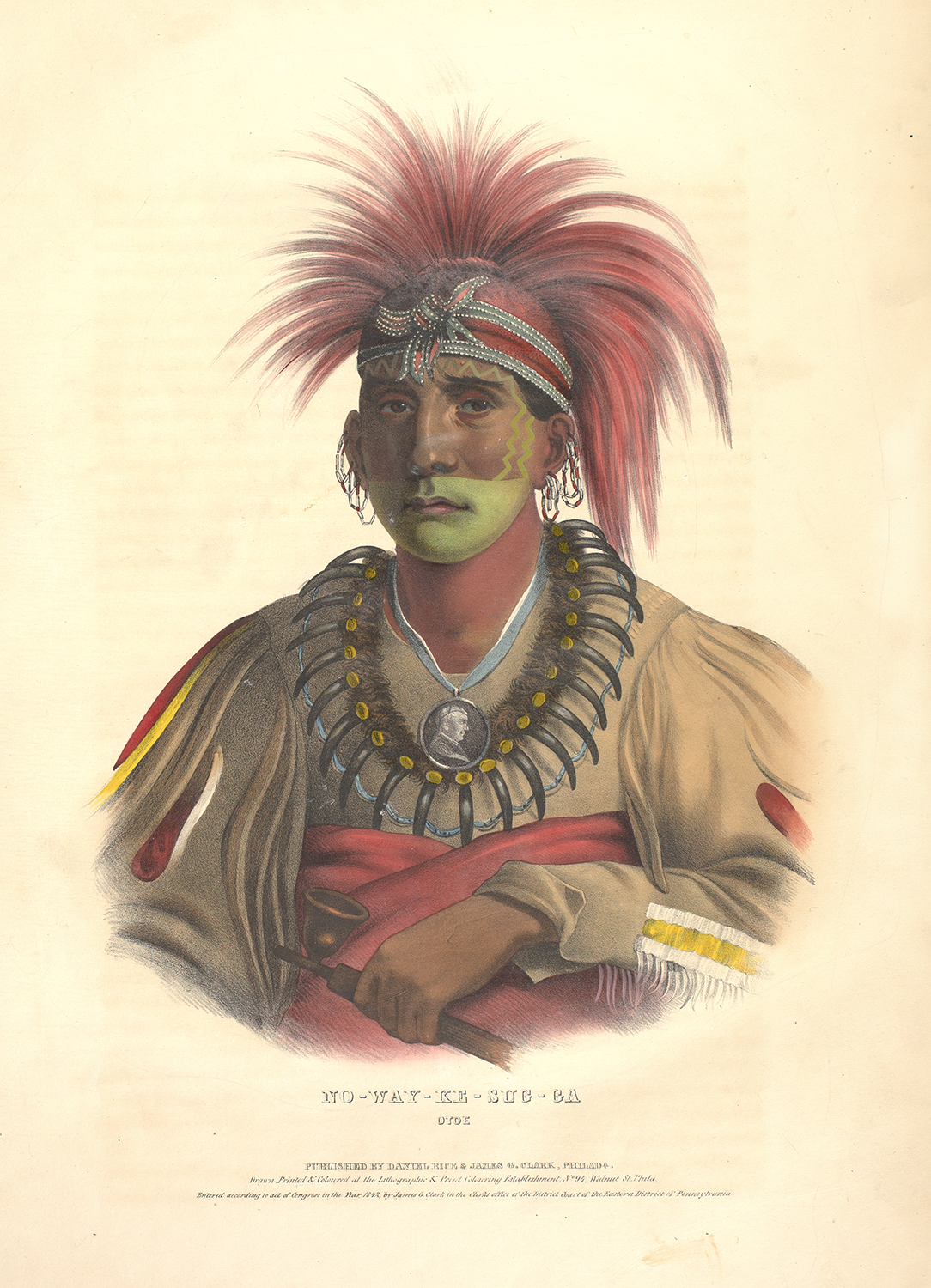

This portrait of No-Way-Ke-Sug-Ga (possibly translated as “He Who Strikes Two at Once”) is one of a set included in the Thomas McKenney (1785-1859) and James Hall (1793-1868) publication History of the Indian Tribes of North America (1836-44). These lithographs, mostly the work of Charles Bird King (1785-1862), are among the most colorful portraits of Native Americans produced in the nineteenth or any century. Many of the original oil paintings on which the prints were based perished in the 1865 Smithsonian Institution fire.

Visitors to The Best of the West, which will run through April 2020, will appreciate that “the west” has evolved as a geographic descriptor over the years. At the same time that Spanish authors like Miguel Benegas, Francisco Palóu, and Josef Espinosa y Tello were writing about Spain’s settlements in California and Mexico, English and American observers were describing the Mississippi River Valley as the farthest extent of settlement and exploration from the East Coast. The exhibit includes Philip Pittman’s 1770 Present State of the European Settlements on the Mississippi, Zadock Cramer’s 1802 Ohio and Mississippi Navigator, and the 1814 first edition of the Lewis and Clark report on their expedition to the West Coast and back. The cases for the middle decades of the 19th century feature Hall J. Kelley, John B. Wyeth, Eugène Duflot du Mofras, and Henry James Warre on Oregon, the George Catlin and McKenney and Hall portfolios of Native American portraits, and rare overland narratives by James O. Pattie, Zenas Leonard, Joel Palmer, and Riley Root. The 1851 George W. Kendall and Carl Nebel folio on the Mexican War and Henry Lewis’ 1855-58 Das Illustrirte Mississippithal display in impressive fashion the chromolithographed images through which many Americans first viewed the West. After 1850 the focus of the exhibit shifts to mining, outlaws, encounters with Native Americans, and the settlement of new areas from Arizona to Idaho, with Nelson Lee’s Three Years Among the Camanches (1859), C. M. Clark’s A Trip to Pike’s Peak and Notes by the Way (1861), John L. Campbell’s Idaho: Six Months in the New Gold Diggings (1864), Thomas J. Dimsdale’s The Vigilantes of Montana (1866), and Thomas F. Dawson & F. J. V. Skiff’s The Ute War (1879) among the titles on display. Viewers will note that a majority of the items in the exhibit came to the Clements during the 1953-1977 directorship of Howard H. Peckham, and I am most appreciative of Howard’s acquisition of so many high points in western Americana that have subsequently soared to prices that would challenge our acquisitions endowments if we attempted to buy them today.

Texas Ranger Nelson Lee (b. 1807) wrote Three Years Among the Camanches (1859), vividly detailing his experiences in captivity. The widespread popularity of Lee’s tale reflected a growing interest in western Americana.

The Best of the West concentrates on printed books and pamphlets, but readers of this issue of The Quarto will learn that the Library has tremendous strength in western American manuscripts, prints, photographs, and maps as well. Our recent acquisition of some 1,100 Native American photographs in the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection has vaulted the Clements to a high rank among American libraries in that important field. As Jayne Ptolemy outlines, the Crittenden Family Papers that Dr. Thomas Kingsley donated to the Library in 2006-07 are rich in source material on California and Nevada in the late 19th century. Clayton Lewis’ article on the Eastman family and their materials in our Norton Strange Townshend Collection hints at the considerable research potential those papers and daguerreotypes offer. Sara Quashnie, Emi Hastings, and Jakob Dopp contribute pieces on the Hill Family Papers, Lily Frémont, and the myth of Welsh Indians respectively. As these essays and the exhibit indicate, the upshot is that the Clements is a tremendous resource for students and scholars alike on the American West. If we are not yet UCal Berkeley’s Bancroft Library for depth and range of primary sources in western Americana, we unquestionably do hold a remarkable variety of materials on the western half of this country from the 17th through the 19th centuries. So if you like historical books, manuscripts, and images, and if you agree with my favorite 1950s-60s songwriter Tom Lehrer that “The wild west is where I wanna be,” you should come to 909 South University Avenue sometime soon and start discovering what we have here.

—J. Kevin Graffagnino

Director, 2008-2019

Flowers of Life and Living

Elizabeth Benton Frémont, known as Lily, became an intrepid traveler from a young age. She was born in Washington, D.C., on November 15, 1842, just days after her father, the explorer John C. Frémont, had returned from his first expedition to the American West.

Lily’s mother, Jessie Benton Frémont, was the daughter of Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri. Jessie had been well-educated by a series of tutors and served as her father’s secretary during her teens. Following John Frémont’s three expeditions west in the 1840s, John and Jessie together wrote the expedition reports which followed his trips, sharing his enthusiasm for western exploration with lively prose and useful information for potential emigrants to the Oregon Territory.

In 1847, John Frémont purchased a large tract of land called Rancho Las Mariposas (renamed Bear Valley), in the southern Sierra Nevada foothills. Although initially regarded as worthless land due to its isolated location, it quickly became highly valuable after the discovery of gold in California in 1848. The Frémonts traveled to California to oversee mining operations and manage his new ranch.

Lily was six years old when she embarked upon her first voyage in 1849, a difficult cross-country journey from Washington to California by way of the Isthmus of Panama. Before the creation of the Panama Canal, crossing the Isthmus was a wearisome trek lasting six days. To Lily, this was a trip to be remembered fondly, in which “each hour was filled with thrilling interest and novelty.” Throughout her life, Lily was drawn to flowers, often describing them in her writings. In her first crossing of the Isthmus of Panama, she vividly recalled her first sighting of “the white and scarlet varieties of the passion-flower, as well as other flowers both brilliant and fragrant, for which I know no name.”

For an adventurous young girl, pressing flowers memorialized in a lasting way the beauty of the landscapes through which she traveled. Writing of her recovery from a dangerous fever, Lily mused, “When life is young . . . and the warm blood courses through the veins, it is not so easy to die. The world was waiting with its arms filled with roses . . . and I was not averse to staying yet a little while, to gather a few of the flowers of life and living.”

Her mother Jessie remembered the voyage differently. As a young, sheltered woman leaving home for the first time, crossing the continent alone with her young daughter presented many challenges. In A Year of American Travel (1878), she wrote: “I had never been obliged to think for or take care of myself, and now I was to be launched literally on an unknown sea, travel towards an unknown country, everything absolutely new and strange about me, and undefined for the future.” About six months after reuniting in California, the Frémonts returned to Washington because John had been elected a California senator.

Lily soon became an international traveler as well. After John had served as Senator from September 1850 to March 1851, the Frémonts decided to travel abroad for a year. They visited England and then rented a house in Paris for over a year. In 1853, they returned to Washington, and soon after John embarked on his last western expedition. After John Frémont’s failed presidential bid in 1856, the Frémonts returned to Paris for a brief stay before journeying back to California in 1858 to settle on their property in Bear Valley.

In Recollections of Elizabeth Benton Frémont (1912), Lily wrote: “Nowhere else did the wild flowers ever seem so beautiful as at Bear Valley, and I rode afar into the mountains in search of them. The Indian men often brought me long withes [willow branches] wound round with flowers, from places inaccessible to me, and the white men of the neighborhood were astounded at this attention of the Indians to a mere girl.”

It may have been these gifts of wildflowers that inspired Lily to create a pressed flower album, now housed at the Clements Library. She started the album in 1859 when she was sixteen years old. The first two pages of the album hold drawings depicting the Frémont home in Bear Valley and a small group of buildings and a smokestack, possibly one of the Frémont mines. The rest of the album contains about eighty pressed flowers and other plants, most of them numbered and annotated with descriptions.

Lily shared her love of flowers with both parents. In published works by all three family members, flowers are often vividly described, even in John’s official expedition reports. In her album, Lily noted two specimens that were her father’s particular favorites, wild heliotrope and another unnamed bloom. Jessie likely taught her daughter how to press the flowers to include in the album. In Far-West Sketches (1890), Jessie recalled that she enclosed “rose-leaves and violets and such-like sweet vouchers” in her letters back home to Washington, which “in their own dear silent way carried messages of comforting and hope.”

Bear Valley, Lily Frémont’s beloved home during the 1850s, from the front of an album holding her pressed flower specimens from 1859.

Lily’s album of pressed flowers began with a buttercup found on January 20th, 1859, and continued through May of that year. Several following pages of specimens are undated, and the final date to appear in the album is January 29th, presumably 1860. The last annotations indicate specimens gathered in San Francisco near the family’s new home at Black Point, to which they moved in early 1860.

As Lily added specimens to her album, she usually noted the date and location, sometimes identified the name of the plant, and often observed its growing conditions, soil, and other notes. She rode far and wide with her father, visiting their mills and mines and gathering plants along the way. Her notes indicate that she gathered specimens in locations as varied as Bear Valley, the Burkhalter hills, Mt. Bullion, Mt. Oso, Lone Mountain, Hell’s Hollow, Mt. Ophir, and Black Point. For specimens she did not personally gather, she recorded whatever information was available. Specimen no. 56 “was given to me so I don’t know about it much. I think it is a bush flower & came from Hell’s Hollow.” No. 75 simply received this brief note: “I remember nothing about.”

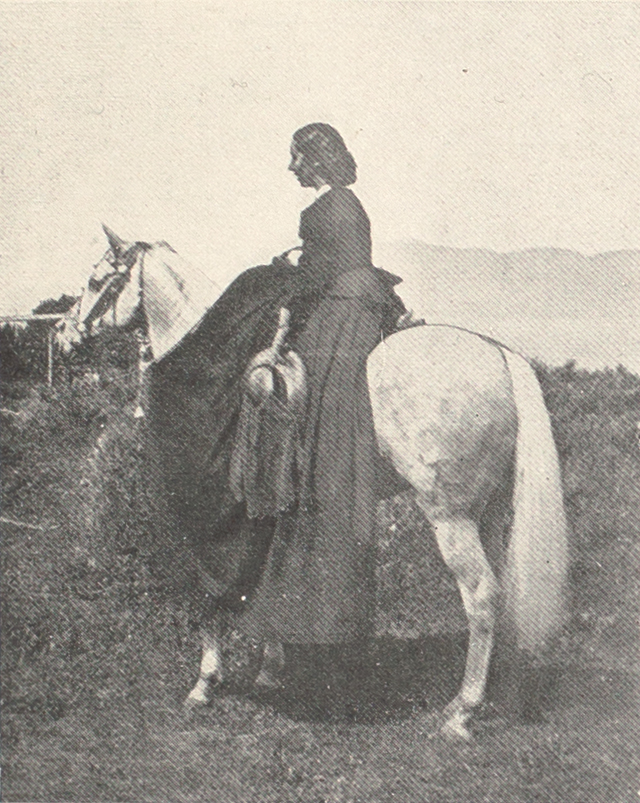

A capable horsewoman, Lily favored two horses for these frequent trips with her father. Ayah was a mountain-bred horse; Chiquita was cream-colored with silver mane and tail. Another horse gifted to her by a cattle ranger, the aptly-named Becky Sharp, turned out to be a little too lively for safety and was swiftly retired after she attempted to buck Lily off three times and then stranded her two miles from home. After moving to San Francisco, Lily was unfortunately not able to gather as many flowers, partly due to her horse: “Chiquita was more restive than Ayah, so I did not care to dismount as I used to in Bear Valley, besides there were always herds of Spanish Cattle around. So I missed many lovely flowers.”

While traveling, Lily observed changes in the landscape caused by mining and other human activities. Wild jasmine grew in the “mining holes” and another unnamed plant in the “small stony hollows and washed out placer ditches.” She reported that wild clover had originally covered Bear Valley and far up the mountainsides, “but some teamsters set fire to it ‒ about two years before we came out ‒ & burned most of it so badly that it has only grown again in especially moist places.”

Lily Frémont on Chiquita.

Lily recorded second-hand information from her father regarding indigenous use of plants, including the “quinine vine” or wild cucumber (“Father says the Indians use its root as medicine in fevers”), the wild sunflower (“I am told that the Indians use the seed”), and an unidentified leaf “which the Indians use as a salad.”

Livestock interactions with native plants were also of interest, such as the wild larkspur, which was “poisonous to cattle, who do not like to eat even the grass near it.” There were large fields of wild larkspur along one road, and she noted “the cattle avoided these plains from the time it began to flower till it passed.” The wild pea-vine, by contrast, was favored by cattle and horses and “gives good nourishment.”

Lily sometimes commented on her own process of pressing and drying the plants. White mariposas blossoms were “rather hard to press well & almost impossible to glue, for the instant the glue touches them, they roll right up, & then it [is] very hard to unroll them.” She was particularly concerned with the effect of drying on the color of the flowers, which she was anxious to describe accurately. For a number of specimens, she noted the original color of a flower that had “faded in pressing.”

In addition to wildflowers, Lily was interested in the more domesticated plants growing around their house, including a live oak and wild clover inside their enclosure, and an unnamed specimen pulled from just outside the fence. Another “tame flower” came from the neighboring “Italian’s garden.”

After the Frémonts moved from Bear Valley to San Francisco in 1860, Lily’s specimen gathering seems to have slowed and then stopped entirely. On her last page of text, she wrote, “Though we had so many many beautiful flowers at Black Point I had never thought of pressing any, & these are only some I pressed ‒ or rather put in this book, for the geranium leaf had been my book mark for weeks ‒ the day before we left home. The mignonette had grown from seeds of my own planting.”

In 1861, following the outbreak of the Civil War, Jessie and her three children left San Francisco for St. Louis while John served in the Union Army. After the war, Lily remained single and continued to travel and live an adventurous life. She eventually settled in Long Beach in 1905, where she remained until her death in 1919.

—Emiko Hastings

Curator of Books

A Profound and Enduring Impression

According to Welsh legend, a royal prince by the name of Madoc supposedly took to the high seas and departed from Wales for new pastures in 1170 after the death of his father led to a bloody power struggle. The tale of Madoc, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, evolved to incorporate the idea that he had actually navigated his way to America and established Welsh colonies, thus conveniently providing a British presence in the New World that predated any and all Spanish claims. In all likelihood, Elizabeth I and her advisors initially deployed the Madoc story strictly as propaganda in order to trump their Spanish rivals. However, the modified Madoc legend ended up taking on a life of its own, especially amongst Welshmen and Welsh-Americans who were exceedingly proud that one of their own might have been the true “discoverer” of the New World.

Over the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, countless rumors were circulated regarding the existence of so-called “Welsh Indians,” descendants of Madoc’s colonists who were believed to have mixed with local Native populations and yet still clung to vestiges of Christian traditions, established fortified European-style towns, and spoke the Welsh language fluently. At first, attention focused on tribes of the Eastern seaboard near locations where Madoc’s colonists were thought to have landed, such as Newfoundland, New England, the Carolinas, and Florida. In John William’s Farther Observations on the Discovery of America, by Prince Madog ab Owen Gwynedd (1791), the famous accounts of Reverend Morgan Jones and Captain Isaac Stewart feature prominently. Jones had claimed to have been captured in 1660 by Indians in Tuscarora country while visiting South Carolina. His imminent execution was prevented only after the Indians heard him praying in the Welsh tongue, which they miraculously understood. Stewart likewise claimed that he was captured around 1766 before being rescued by a Spaniard and a Welshman named John David. During their subsequent adventures, the company crossed “the Mississipi near Rouge or Red River, up which we travelled 700 Miles, when we came to a Nation of Indians remarkably White, and whose Hair was of a reddish Colour.” John David was reportedly astounded to find that these people were also able to speak Welsh.

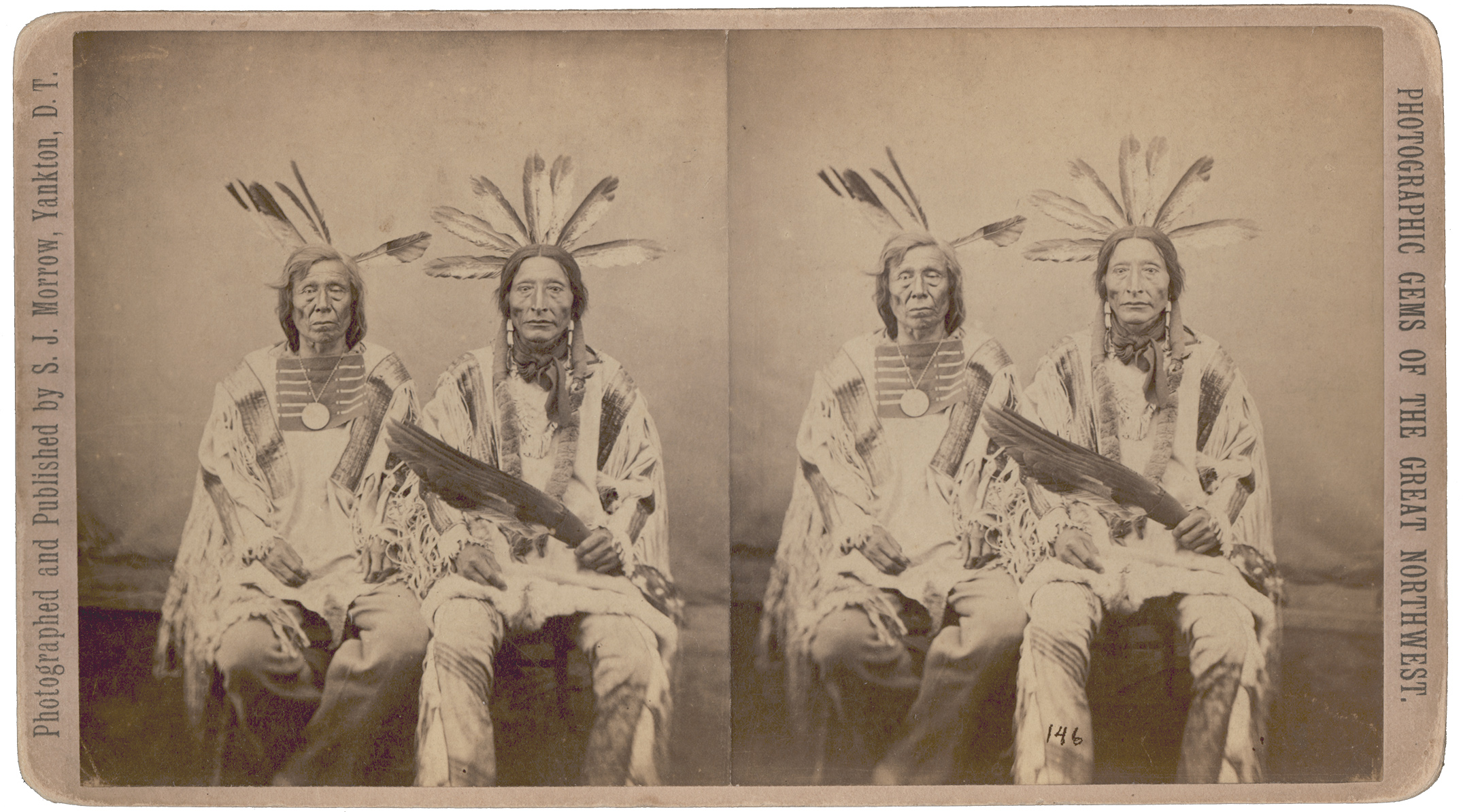

Photographer Stanley J. Morrow (1943-1921), active in the Dakota Territory region during the late 1860s and 1870s, alluded to the Welsh-Mandan theory in a caption on the back of this image, which reads, “1st and 2nd Chiefs of the Mandans, descendants of a colony of Welch.” This caption indicates that enough people were familiar with this idea to warrant Morrow using it as a marketing point.

Reverend Bowen also referenced a letter published in the Kentucky Palladium in 1804 by a Mississippi judge, which stated that “No circumstance relating to the history of the Western country probably has excited, at different times, more general attention and anxious curiosity than the opinion that a nation of white men speaking the Welsh language reside high up the Missouri.” In fact, many early explorers of the American West, such as Lewis and Clark (who were instructed by Thomas Jefferson, himself of partial Welsh descent, to be on the lookout for Welsh Indians), considered the discovery of Madoc’s descendants a bonus subplot of their missions.

The works produced by Swiss-French artist Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) during the Weid Expedition of the early 1830s are considered to be some of the most important and accurate visual depictions of indigenous peoples and natural landscapes from the early days of exploration in the American West. In this detail of a rendering of a Mandan settlement called “Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch,” villagers can be seen operating the fishing boats that George Catlin and others so strongly believed to be derived from the Welsh coracle.

Needless to say, all theories regarding the existence of Indian tribes descended from a renegade 12th-century Welsh prince have long proven to be false. English skeptic Thomas Stephens vigorously disputed many of the popular narratives of his day and age that were associated with Madoc and the Welsh Indians in his Madoc; An Essay on the Discovery of America by Madoc ab Owen Gwynedd in the Twelfth Century (1893). Reverend Morgan Jones’ captivity story was shown likely to be nothing more than an elaborate hoax, while Catlin’s comparative linguistic analysis of Welsh and Mandan was demonstrated to be a laughable misrepresentation of the facts. However, Stephens found his efforts at undermining the Madoc legend’s legitimacy surprisingly difficult, particularly with regards to individuals of Welsh extraction who continued to defend it. According to Stephens, “The tales told respecting the Welsh Indians found favour with many persons . . . but in Wales itself they produced a profound and enduring impression.”

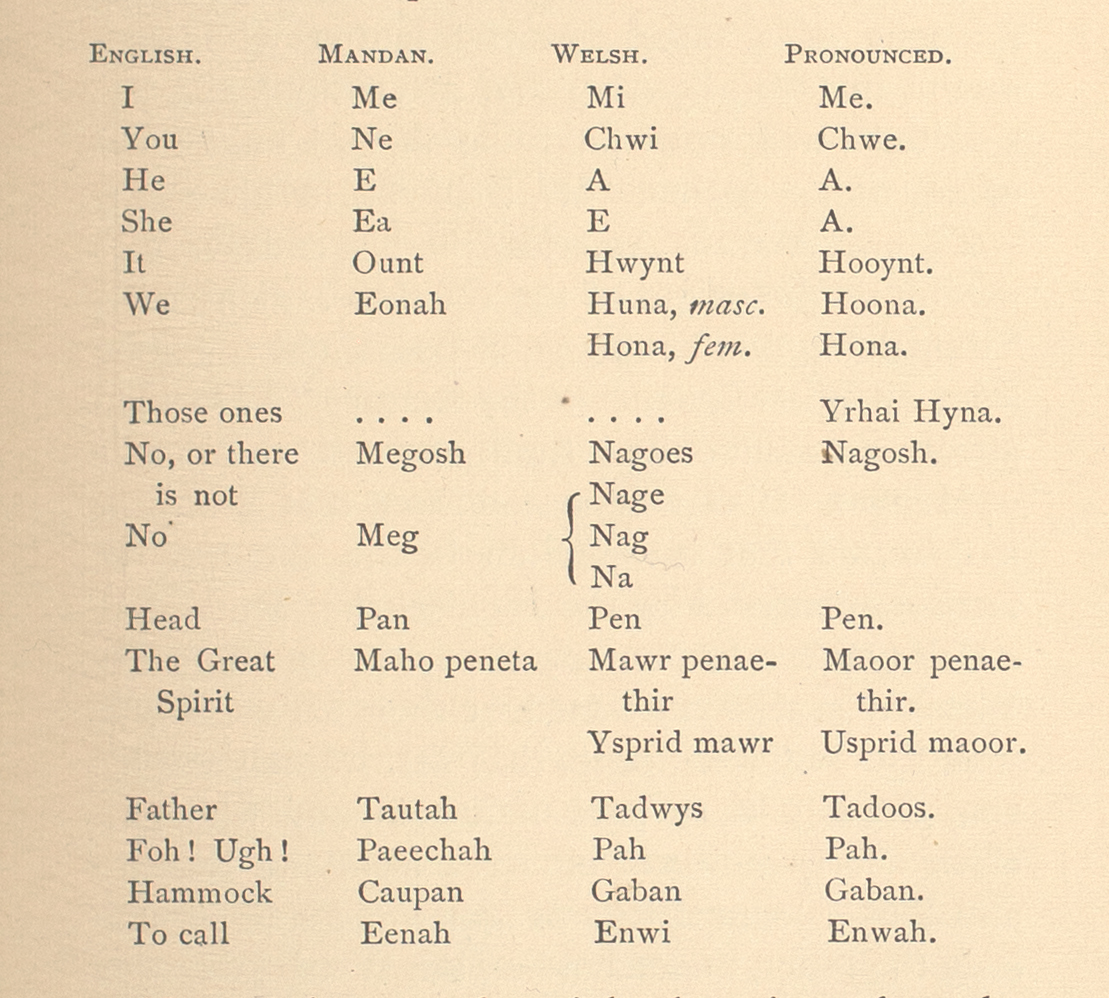

Comparative analyses of Mandan and Welsh words with supposedly similar phonetics and meanings, such as this table included in Bowen’s America Discovered by the Welsh, were considered by Catlin and others to be irrefutable evidence of the tribe’s Welsh heritage.

—Jakob Dopp

Cataloger, Graphics Division

Golden Dreams, Waking Realities

One such dreamer, Alexander Parker Crittenden, hailed from a beleaguered family in Kentucky. As he worked to extract his widowed mother from debt in 1837, he fell hard for the strong-willed Clara Churchill Jones. The Clements Library’s Crittenden Family Papers document their early courtship, when he wrote frequently to Clara, cross-hatching his letters to double the amount of starry-eyed remembrances he could fit into one mailing. “You must, indeed you must,” he implored, “keep that wandering spirit of yours at rest, else I shall be forced to find some charm to quiet it. A kiss every night would be effectual, but how is this to be accomplished when there is such a distance between us. There is but one course ̶ to appeal to yourself not to appear to me in my dreams. ’Tis such a disappointment when awakening to find it all but a dream.” A young man of 21, Alexander found his mind occupied with love and desperate attempts to secure his financial footing to assure the Churchill family that he could support a wife. His dreams for the future were entangled with his dreams of Clara. He sheepishly admitted that in his pursuit of success, “I must lead an unsettled life, and in all probability soon be compelled to go south or West.”

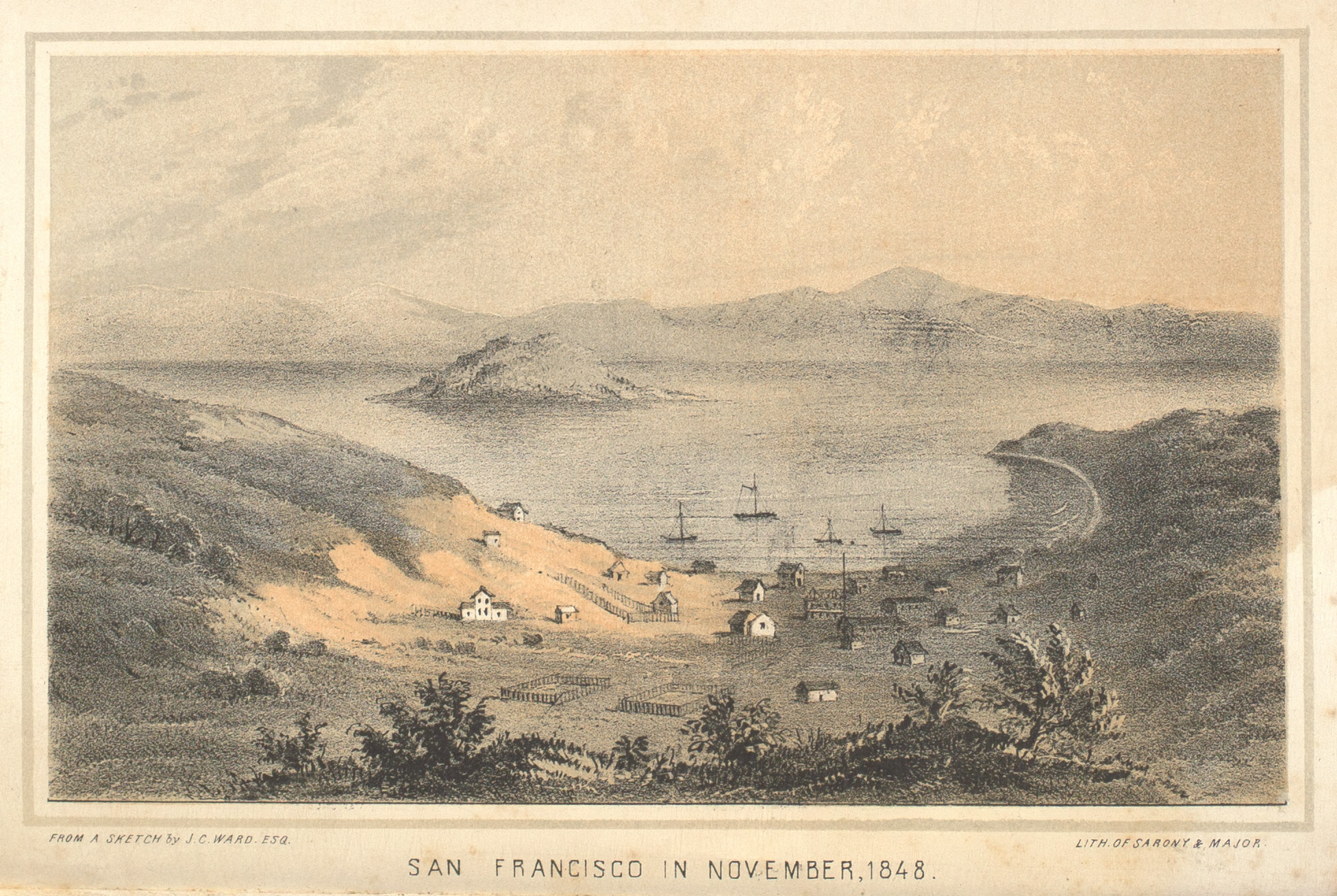

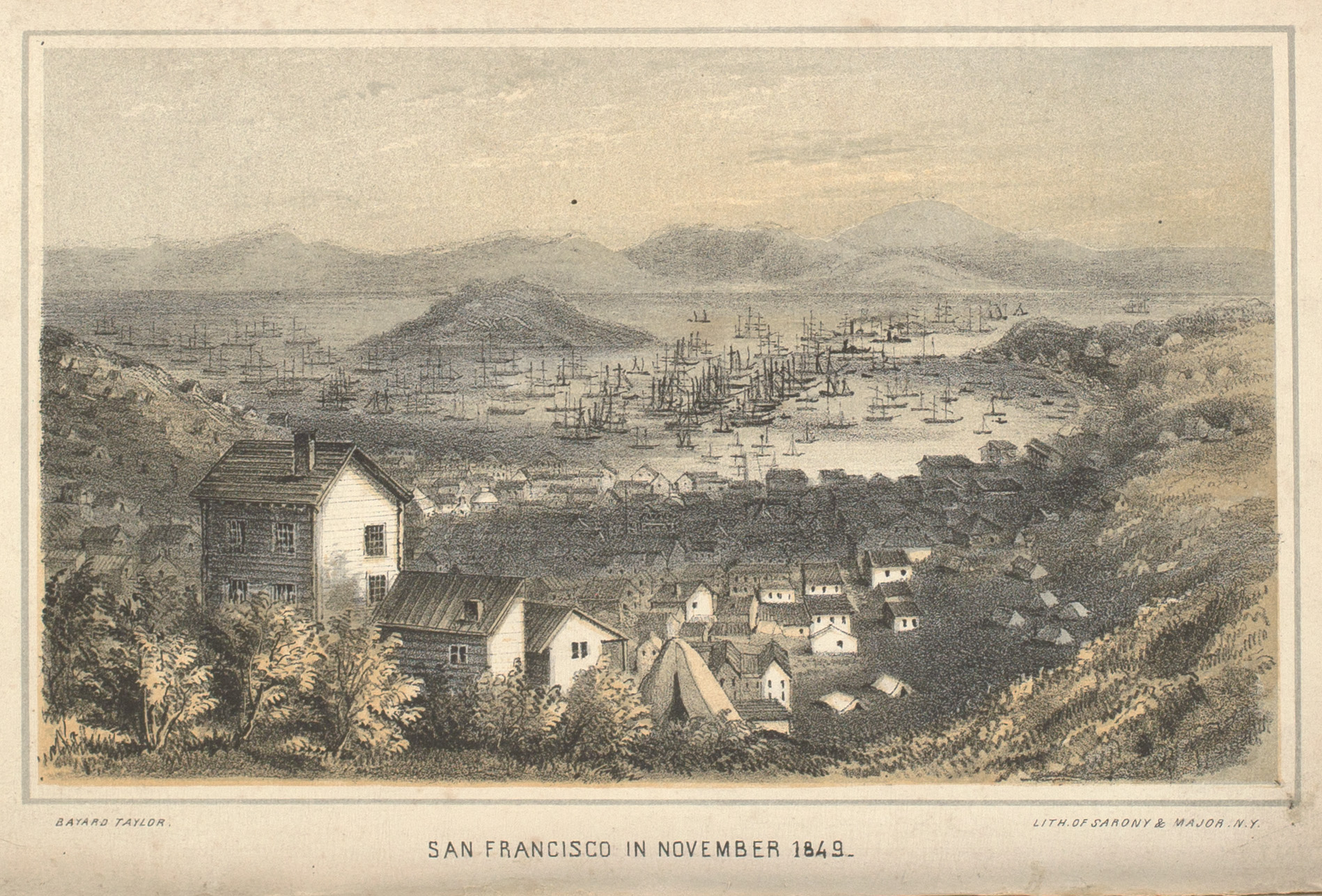

Californian cities grew at a bewildering pace. Bayard Taylor, sent by Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune to report on the Gold Rush, noted in his book Eldorado (1850) that “People who have been absent six weeks came back and could scarcely recognize the place.”

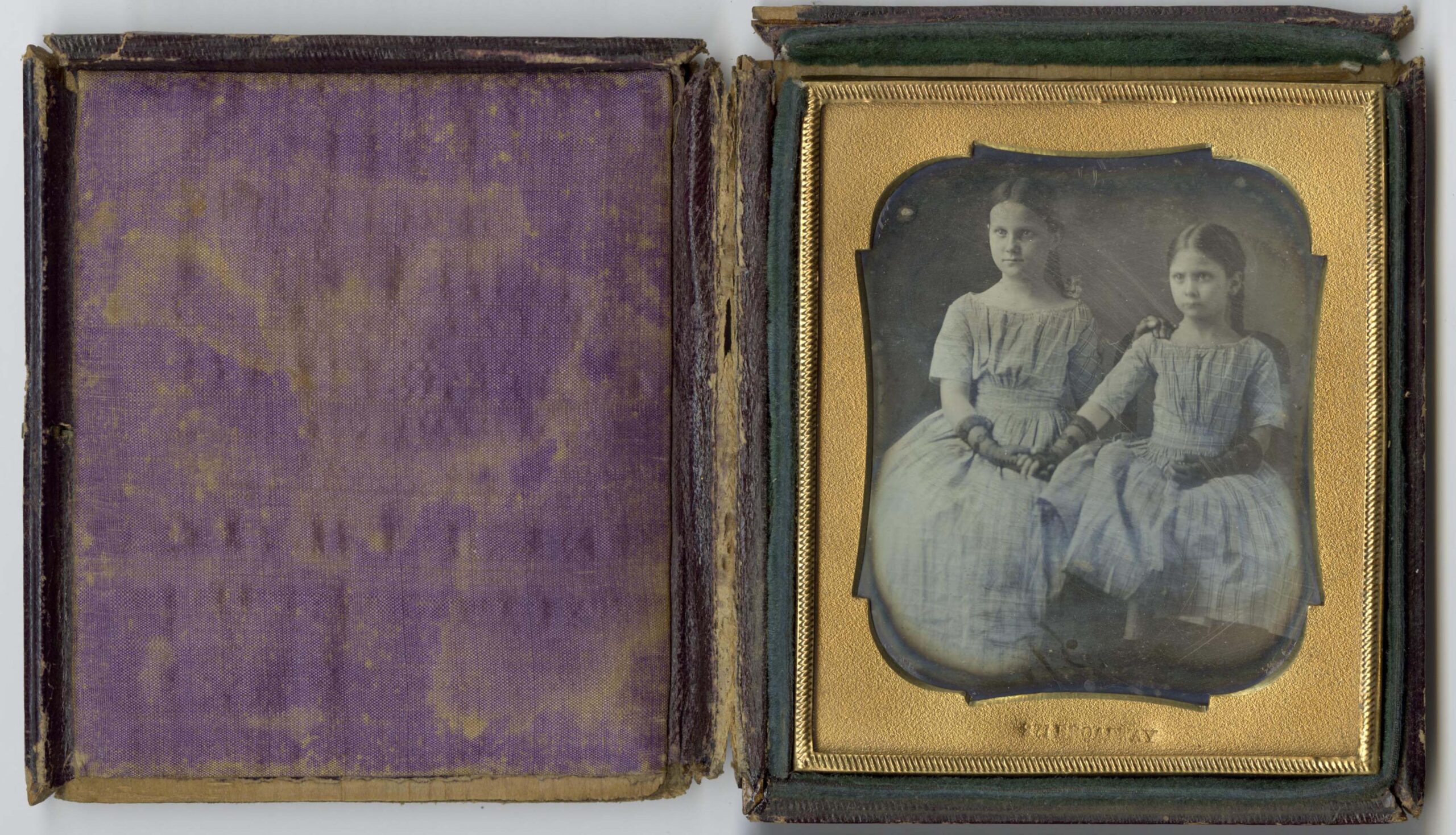

Human connection was closely prized by those in the western city. When a great fire rushed through San Francisco in May 1851, Alexander described how he went about trying to save his possessions. “I had not much to lose,” he admitted. “The most highly prized of all my goods & chattels were your portraits. They were the first things I thought of. I did not know how to secure them. I tried to put them in my pockets ̶ but reflecting that they would be injured, perhaps destroyed by the fire and water to which I must be exposed ̶ I concluded that the trunk was the safest place for them until the moment came when we should be compelled to retreat.” Surrounded by a city engulfed in flame, “a perfect sea of fire roaring and rushing around us with a sound louder than the breaking of the waves on the shore,” Crittenden held on tightest to the daguerreotypes of his family, his connection to those he left behind as he chased visions of success. He was thoughtful about sending Clara pictures of himself as well. One he sent in October 1850 after his plans to visit her were dashed once again by a financial setback, “a blow almost too heavy to bear.” “If I cannot come in person I will send my image. It is the best I can do, but it is a poor substitute. It is deficient in the warm heart beating only for you. It cannot open its lips and tell you how dearly you are loved.” Alexander’s dreams had shifted from earning a great fortune to finding a way to be together again. “I wish we could live upon affection and that that most hateful of all words ̶ money ̶ might never be mentioned again.”

This photograph of Alexander’s eldest daughters Laura and Nannie Crittenden was likely taken sometime around 1851, posing the alluring possibility that it could have been one of the daguerreotypes he guarded so carefully during his early years in San Francisco.

In 1851 British sailor William Shaw published Golden Dreams and Waking Realities: Being the Adventures of a Gold-Seeker in California and the Pacific Islands. Lured by the promise of Californian wealth, Shaw set out for the mines. After a grueling attempt, he abandoned the dream, packing his belongings to seek better prospects. “The wind was blowing hard and the rain pelted heavily down, as giving a last long look at the diggings, I thought of the golden dreams and buoyant hopes which had lured us to them; and turned my back upon a spot where these had been so rudely dispelled by the waking realities of privation and suffering.” Many fortune-seekers were drawn to the promise of California by stories of successful mines, of gold dust blowing in the streets, of cities erupting into being and bustling with newcomers and opportunities. But mining proved difficult, unsteady work, requiring far more financing and luck than most had. And even those who were drawn to the coast not by gold but by the attendant boom it brought to the region, found that life in the new West could be risky. The speculative frenzy that undergirded San Francisco’s growth could tumble even the most optimistic of men. Alexander Crittenden struggled alongside them. Working for years to secure a strong enough footing to bring his family with him to California, his dreams of financial freedom waned in the face of homesickness and separation. And in turn, when his family was reunited, happiness again failed to follow. Love and stability, like his dreams of fortune, were always a step or two ahead of him. San Francisco may have sprouted from Americans’ dreams, but that doesn’t mean they always came true.

—Jayne Ptolemy

Assistant Curator of Manuscripts

Across Two Worlds

On the great plains of the American West amidst the tension between settlers and decimated tribal communities, one remarkable family represented a range of perspectives on the Native American experience. Connected both to old stock from New England and tribal chiefs from west of the Mississippi, the family included a U.S. Army artist and engineer enforcing Indian removal policies; an author both sympathetic and condescending as she recorded Native lore; and a Native American physician, who endorsed assimilation only to return to Native homelands just as the violence of the Indian Wars exploded in a horrendous final bloodbath. Each sought to record, reflect, educate, advocate, and understand on both a public and a deeply personal level what it meant to be Native American. The Clements Library is lucky to house photographs, original art, and published works relating to the Eastman family.

Seth Eastman (1808-1875) was a skilled artist and topographical engineer from Maine, educated at West Point. His legacy as an artist includes paintings of U.S. military sites on display at the United States Capitol as well as hundreds of illustrations for government publications and books by his second wife, Mary. Seth frequently sketched Native American subjects, scenes, and artifacts while stationed at Fort Snelling near what is now Minneapolis, Minnesota. At the time of his first arrival there in 1830, the region was the home of the Santee Dakota Sioux people.

Shortly after he arrived at Fort Snelling, Seth married a fifteen-year-old Native woman, Wakinajinwin (Stands Sacred, b. ca. 1815). She was the daughter of Mdewakanton Santee chief, Mahpiya Wicasta (Cloud Man, b. 1780), who was among the first of his people to shift towards an agricultural lifestyle and convert to Christianity. In the same year as her marriage to Eastman, Stands Sacred gave birth to a daughter named Winona (First Born Daughter, 1830-58). Winona also became known as Mary Nancy Eastman, and later as Wakantankawin (Holy, or Sacred Woman) following the Sioux tradition of changing and adapting names to reflect life’s events.

After three years, the U.S. Army reassigned Seth to West Point. He then declared his marriage ended, abandoning his young wife and child, although possibly leaving behind some means for their support. They could not have known that their paths would cross again.

In 1835, while stationed back at West Point, Seth Eastman married a second time, to Mary Henderson (1818-1887), daughter of a military surgeon. In 1841 Eastman was again assigned to Fort Snelling, this time for an extended tour of duty as commander. He thus returned to the haunts of his first family, bringing his new white wife. Together, Mary Henderson Eastman and Seth would have seven children, some of whom were born during their time in the West.

Fort Pembina, Dakota Territory, circa 1858. This evocative small watercolor by Seth Eastman shows the virtuosity that ranks him with the greatest artists of the American West. Situated on the northern border with Canada, Fort Pembina was a trading post going back into the 18th century. Eastman was in this vicinity in 1857-58, having been sent back to Fort Snelling to close down operations there.

At Fort Snelling, Mary and Seth Eastman found plenty of opportunities to deepen their fascination with Dakota culture and lore. Their first-hand experiences with the indigenous people of the West, along with Seth Eastman’s advanced artistic skills, would in later years situate him for the editing and illustrating of Henry Schoolcraft’s landmark government report Historical and Statistical Information respecting the History, Condition, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (1851).

Mary, an assertive and inquisitive woman, drew the attention of tribal elders around Fort Snelling, who eventually began to share their stories and legends. These became the basis of several publications by Mary, among them Dahcotah, or Life And Legends Of The Sioux Around Fort Snelling (1849); and Romance of Indian Life: With Other Tales, Selections from the Iris, An Illuminated Souvenir (1853); both of which featured color lithograph illustrations based on her husband’s artwork.

The written works of Mary Eastman have long been considered sympathetic portrayals of Sioux culture. However, by 21st-century standards, they represent a condescending point of view, blurring romantic notions of chivalry and valor together with the very different Native perspective. Sentimentality overwhelms truth, and the veracity of the narrative becomes questionable. Themes of loss, romance, cruelty, jealousy, and vengeance dominate the lives in her stories.

It is not clear at which point Seth Eastman and Stands Sacred’s daughter Winona took the name Wakantankawin (Holy, or Sacred Woman). In 1847, she married Ite Wakandi Ota (Many Lightnings, 1809-1875), who descended from Wahpeton Santee Dakota chiefs. As evidence of familial bonds among this community, the Eastman name was adopted by Many Lightnings and his children after Sacred Woman’s death during the birth of a son in 1858.

Sacred Woman and Many Lightnings’ son Hakada (The Pitiful Last) was destined for an odyssey across lands and cultures. His shifting and self-invented identity would bring new names. His first references the death of his mother during childbirth. At age four, his tribal band won an important lacrosse game and gave him the name Ohiyesa (The Winner). And yet another designation was to come.

Ohyiesa’s father, Many Lightnings, embraced assimilation, converted to Christianity, and changed his name to Jacob Eastman. He determined to steer Ohiyesa on a path away from confrontation and toward assimilation. This achieved, Ohiyesa chose the name Charles Alexander Eastman and began an academic career through numerous missionary programs, Indian boarding schools, and colleges, eventually graduating from Dartmouth in 1887. He then entered Boston University, earning a medical degree.

By November 1890, Dr. Charles Eastman had returned to the West as a medical officer at the Pine Ridge Indian Agency in present day South Dakota. At Pine Ridge tensions between the U.S. Army and desperate Lakota followers of the Ghost Dance movement were reaching the point of violence. On December 29, 1890, the Seventh Cavalry (the unit formerly led by George Armstrong Custer) massacred a Miniconjou band of men, women, children, and the infirm at Wounded Knee Creek. Eastman was on the scene, scrambling to provide care for the wounded and traumatized survivors scattered across the frozen prairie.

Seth Eastman’s artwork, including “Itasca Lake” (circa 1851), illustrated the publications of Henry Rowe Schoolcraft as well as those of Mary Eastman. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow drew heavily on Schoolcraft’s, and likely Eastman’s, work in imagining scenes for another Native American Romance, The Song of Hiawatha (1855).

Disillusionment and revulsion pushed Dr. Charles Eastman to New York, where he married New England educator Elaine Goodale (1863-1953) in 1891. For the next 20 years Eastman held various positions with the federal government, the Carlisle Indian Boarding School, and numerous other organizations that advanced understanding of Indian cultures. He promoted the YMCA and Boy Scouts of America on western reservations, collected artifacts for the University of Pennsylvania, and wrote and lectured on Native American conditions, becoming one of the most prolific authors and speakers on Sioux ethno-history and American Indian affairs.

Frustration followed achievement throughout Dr. Charles Eastman’s career. His descriptions of the aftermath of Wounded Knee and the effect it had on him made clear that he was questioning “the Christian love and lofty ideals of the white man.” He found that he was an outsider in both worlds ‒ not militant enough for many Native Americans angered by harsh assimilation programs, but far too “Indian” for many of his white colleagues. He endured dismissive criticism. The Springfield Republican commented that his personal experiences offered “little social or educational value.” His efforts to establish a medical career in Minneapolis were frustrated by expectations that he could also prescribe a magical “Indian medicine.”

In the Petoskey, Michigan, region Charles Eastman crossed paths with Grace Chandler Horn (1879-1967), a talented artistic photographer who sold photos of the local Odawa and Ojibwe residents to tourists. Although her staged photographs sometimes misrepresent her Native subjects, her work is aesthetically beautiful (evidenced by this photograph of Charles Eastman, ca. 1920) and in step with the important Photo-Secessionist style of the day.

As he sought ways to reconnect to the values of his indigenous upbringing, he found his way north, back to the traditional Santee homelands of Minnesota and into Ojibwe and Odawa territories. In the 1920s and 1930s Eastman was frequently back and forth between the Lake Huron shore and the Detroit area, where his son Ohiyesa II lived. In From the Deep Woods to Civilization (1916) a revitalized Eastman commented that “Every day it became harder for me to leave the woods.”

Ohiyesa, Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman, died in 1939 of complications from smoke inhalation from a tepee fire. He is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Detroit. He had witnessed the peak of violence between Native American peoples and the United States, experienced both the timeless traditional lifestyle of Plains Indians, and assimilated into 20th century white society. His perspective across two worlds remains relevant in our current multi-cultural society, challenged by issues of race and sustainability.

Although Charles probably never crossed paths with his grandfather, Seth Eastman, the combined experiences and historical record left by Charles, Mary, and Seth Eastman cover a remarkable portion of the complicated and fraught relations between indigenous Americans and others.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics

“I dread it more than tongue can tell”

On June 14, 1864, after a week’s journey amid miles of prickly pear and vast plains, Nathaniel P. Hill (1832-1900) sat down and wrote a letter to his wife. Hill was a former Brown University chemistry professor hoping to make his fortune smelting precious metals in the Colorado Territory while his wife, Alice Hale Hill (1840-1908), remained in Providence, Rhode Island, with their two young children, Crawford and Isabel.

The Hill family’s experience of “going West” was not the narrative typically associated with American western expansion. They did not pack their worldly goods into a covered wagon bound for a homestead claim. Nathaniel Hill was not a miner or railroad worker laboring to forge a fortune from the dirt. Instead, the Hills were an affluent middle-class family from Providence who transplanted their lifestyle from Rhode Island to Colorado following several years of Nathaniel Hill’s business ventures there. Despite the misgivings of his wife, Alice, Hill’s East Coast capital was key to establishing a comfortable standard of living for himself and his family, one that far exceeded his wife’s initial fears. With his scientific education, business connections, and stable financial backing, Nathaniel Hill was in an optimal position to invest in land and innovative technical processes to turn a profit in an industry that destroyed so many dreams. He ultimately succeeded in founding a highly lucrative smelting company and held various public offices in the territory and later state.

While Nathaniel Hill’s early time in Colorado was far from luxurious ‒ reliable travel within the territory was often only by horseback, diet was comprised of meat and eggs, and accommodations were rustic whether in a building or camping in the open with the mosquitos’ “best representatives” ‒ these were temporary inconveniences. Descriptions in his letters back home of his experiences and the people he met reflected the perspective of a well-off outsider. Hill traveled via railroad, stagecoach, and horseback on his initial journey. During the Nebraska leg of the trip, he and his travel companions encountered several of the vast wagon trains streaming across the territory. As he noted in a letter to Alice, many of the emigrants were fleeing Civil War- inspired guerilla actions in states such as Arkansas for destinations to be decided upon reaching the mountain passes.

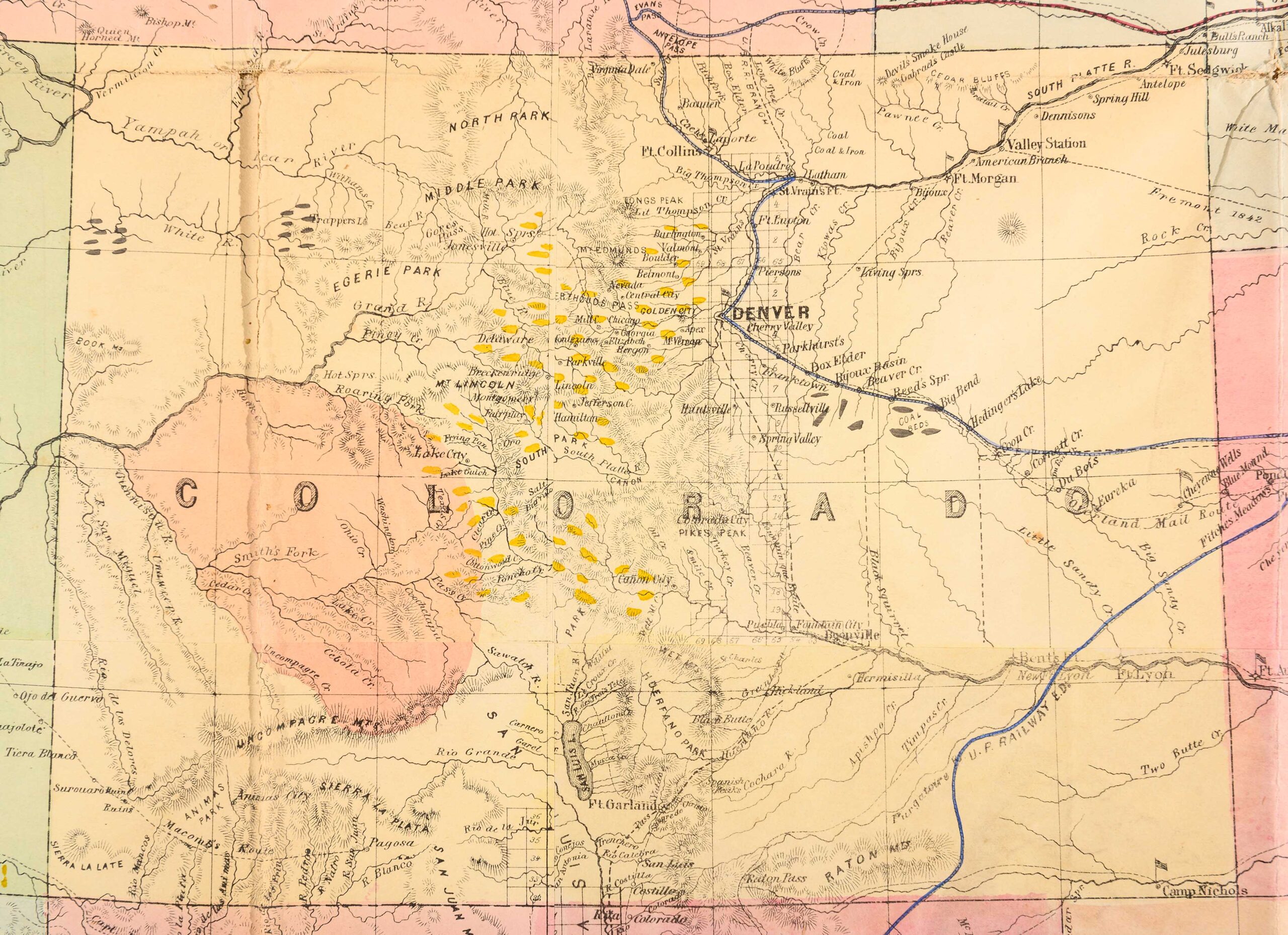

William Keeler’s 1867 National Map of the Territory of the United States included a compilation of data from many governmental sources and was color coded to show the locations of gold, silver, copper, quicksilver, iron, and coal. The yellow markings on this detail of Colorado indicate gold deposits. Keeler’s map has been described as the largest and finest map of the West as it was then known, particularly for its depiction of the post-Civil War railroad system. The map was also issued in a folding pocket-sized edition in 1868. The Clements copy of the smaller map was carried West by a railway contractor and was present in his pocket at the driving of the Golden Spike establishing the transcontinental railroad.

It was stories such as these that fueled the public’s imagination of the “frontier.” Such accounts made their way into newspapers and magazines and subsequently shaped the perceptions of Alice Hill. Separated from her husband by a vast distance, Alice’s knowledge of Colorado was based on published reports and Nathaniel’s firsthand observations. Her mind was preoccupied by the dangers of Native American attacks as touted in newsprint and Nathaniel’s “wild way of living” (though by the time the letter was written where she lamented this fact, Nathaniel had employed a servant). His early letters and information passed on by other acquaintances had a strong influence on her perceptions of life out West. In an October 13, 1867, letter Alice wrote to Nathaniel of the preparations she planned for the family’s eventual move to reunite with him. Much of the letter was devoted to her supply lists and conjecturing about what items would be unavailable in Colorado and how to transport their possessions. Of her everyday purchases, she made particular note of sewing supplies (buttons, elastic, and whalebones) and nonperishable food (corn starch, tapioca, hops, and foreign pickles) to purchase before they left as they would store well and alleviate the need to purchase at exorbitant prices out West. While many families stocked up before moving cross-country, the fact that Alice Hill confidently recommended purchasing multi-year quantities of a variety of food stuffs and dry goods along with her envisioned means of transportation (renting a car, likely a railroad car?) indicated that the Hill family sought as little disruption from their previous mode of life as possible and had the means to make it so.

These logistical details were only part of Alice’s concerns about moving. Leaving family, friends, and the city she had lived in for most of her life would have been extremely difficult in any scenario. The fact that the family was not only completely uprooting but that they were doing so to a remote and largely unsettled region presented a considerable challenge. “I dread it more than tongue can tell,” Alice wrote to her husband, “Of course, only for your sake is the sacrifice possible. To think of exiling ourselves for a long time is dreadful to me. In five years we shall be forgotten by most of our friends here, who are now so dear to me. I don’t think I shall like the people in Col. & I am sure of being a domestic drudge.” This letter in particular, written as the time for the family to join Nathaniel grew ever closer, expressed a litany of Alice’s apprehensions. The correspondence from this period does not include Nathaniel’s replies which Alice referenced. It appears though that his information regarding the living situation in Colorado was inadequate at best. “I am about discouraged by the lack of any real information in any of your letters” she wrote as she pressed for word of their future home, “You can surely tell me as much as this ‒ Is there a house of six or eight rooms where we can live, or shall it be in two?” It seems that Alice Hill was unsure which scenario would be her fate ‒ a smaller scale version of her current home or a frontier hovel more akin to those of the public imagination.

Denver sprang up in the late 1850s in response to the discovery of gold at the base of the Rocky Mountains. The supply of gold proved limited, but the determination and ambition of early settlers ensured that Denver would avoid the fate of many a boomtown when the mines ran out. Downtown Denver was largely destroyed by fire in 1863, but had been re-built by the time this photograph was taken ca. 1869.

Uncertainty did not sit well with her, especially as she attempted to reconcile her current way of life to the anticipated one in Colorado. As she was unable to find someone in Providence to provide housekeeping in Colorado, she feared her days out West would be filled with menial housework. “All the hardship of housekeeping comes on the woman. She is responsible ‒ I know the husband furnishes money, but that is an easy matter compared to washing, ironing, cooking, washing dishes, pots & pans all smoked up by pine wood, sweeping, dusting, sewing, mending & yet all the time look neat.” Alice was keenly aware of the often underappreciated labor required to keep a household running efficiently. As the acting head of household in Nathaniel’s absence, she managed a home (with staff assistance), parented their two children, and handled business affairs for Nathaniel in his stead. The autonomy with which Alice acted on household and financial matters was indicative of a deep trust between the two partners. She kept him apprised of her actions and at times sought advice, but it is evident she made decisions with a fair degree of independence and the candor in her letters to Nathaniel further evidenced a close partnership.

In contrast with many less affluent families, this close relationship combined with sufficient resources gave the Hills the option to remain separated with Alice and the children remaining in Providence and Nathaniel running the Colorado business. Alice may well have chosen to continue such an arrangement if it were not for her deep love for her husband. Time and again, Nathaniel and Alice noted the pain of the other’s absence and their yearning to be reunited. While Alice voiced her many reservations about moving West, she was willing to pay the price. “I am most heartily tired & sick of living away from you, & will pleasantly agree to most anything which will bring us again constantly with each other.” She parted with everything she knew and loved in order to be with him.

By the time these photographs were taken, ca. 1890, the Hills were established Denver citizens. Alice Hale Hill was the daughter of a Providence, Rhode Island, watchmaker. She was a student at the Troy Female Seminary before her marriage to Nathaniel P. Hill on July 26, 1860.

As it turned out, Alice and Nathaniel Hill did not face the amount of hardship that Alice so feared. Three years after moving West, the Hills resided in a comfortable $30,000 home with Mary Halpin, an Irish woman, working as live-in domestic help. Nathaniel spent his days working in the company offices and Alice managed the family sphere. Although she did at times battle with the dust creeping into the house, there was still time for social calls and visits from friends. They attended dinner parties and partook of a varied diet which included dishes such as oysters, sandwiches, ice cream, and champagne. Strawberries even made an appearance though Alice noted that they were rare. The arrival of the railroad certainly helped increase the availability and variety of goods while it also allowed the Hills to maintain close relationships with loved ones back in Rhode Island. Alice’s sister Bell visited several times, and Crawford and Isabel returned to Providence for schooling, with their parents making regular trips to visit.

In the end, the move to Colorado proved a fruitful one for the Hill family. Nathaniel Hill’s Boston and Colorado Smelting Company attained great financial success after his introduction of Welsh smelting practices to Colorado mining operations. The family lived comfortably in Black Hawk and later Denver with live-in household staff, though the children (a third child, Gertrude, was born in 1869) were sent back East for schooling. Following Hill’s term as mayor of Black Hawk, he continued his political career with a term as United States Senator for Colorado from 1879 to 1885. Alice became a leading figure of Colorado society in her own right, earning a place in Representative Women of Colorado (1911) alongside her two daughters. She continued in charitable work, serving as president of the Denver Free Kindergarten Association and of the YWCA. They regularly traveled back East to see family and friends, made extended trips to Europe, and lived in Washington, D.C., during Nathaniel’s senatorial term. The story of the Hill family and their move West is not that of a “wild way of living” feared by Alice, but rather an extension of their previous life back East and the security and privileges it afforded.

—Sara Quashnie

Library Assistant

Developments — Winter/Spring 2020

With Kevin Graffagnino’s retirement, long-time Clements Library Associates Board member Clarence Wolf has commented that it is, “the end of the era of the bookman.” It is fitting then that for his final exhibit and Quarto, Kevin focused on books. In fact, many Clements Library Associates have enjoyed calling Kevin over the years just to share in the “mad-dog” spirit of collecting.

For many of us, the title “Best of the West” may evoke an image of the classic western movies of the 20th century. Our collective socialization toward these stereotypes actually illustrates how important the Clements Library is for telling the stories of all people. My father, a member of the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe, once told me that as a child he loved playing “cowboys and indians.” When I asked him which role he played, he said, “the cowboy ‒ because he is the hero.”

As we continue to fill the gaps in our collections to tell a more complete story of the people of America, we are pleased to announce the availability of the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography. The acquisition was made possible through the generosity of Tyler J. and Megan L. Duncan of Minnesota and Richard Pohrt Jr. of Michigan. Processing and cataloging was funded by both the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation of New York and the Frederick S. Upton Foundation of Michigan. You can read more about this acquisition at http://myumi.ch/dOddj. Our work with this collection will continue as we utilize funding from the Upton Foundation to create a traveling exhibit allowing more people to learn about these historic materials.

As we transition to the leadership of the next Director, I look forward to more collaborative, innovative, and monumental projects. These big ideas are only possible with the support of people like you. We need your enthusiasm for what we do and your financial contributions. I am always happy to grab a cup of coffee and dream with you about what we can accomplish together at the Clements Library!

One big project the staff is working on is an ambitious set of new digitization goals. Our ability to present all the heroes, villains, and everyday people to a broader audience enhances the possibilities for new insights and better connections. A first step towards expanding our digital resources was a complete overhaul of the Clements Library website. Please check out the new offerings at clements.umich.edu.

We are delighted to have Director Paul Erickson on board. He and I will be traveling the country during the next few months, because we can’t wait to include you in our plans for the future of the Clements Library and to hear your ideas. If you would be willing to host a small gathering, please contact me at [email protected].

—Angela Oonk

Director of Development

Examining the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography, (L-R) Cataloger Jakob Dopp, CLA Board Member/Collector Richard Pohrt, Eric Hemenway and Graphics Curator Clayton Lewis. Hemenway, director of archives and records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians, was one of the consultants from indigenous communities that were sought out to advise the Clements Library.

Celebrating Kevin Graffagnino

As a new year begins, we congratulate our first Randolph G. Adams Director J. Kevin Graffagnino as he embarks on retirement. During his tenure, Graffagnino oversaw a comprehensive renovation and expansion of our 1923 building, shepherded major new collections acquisitions, and more than tripled the endowment funds. Kevin’s leadership and dedication have produced a lasting legacy at the Clements. On Tuesday, December 10, 2019, colleagues, board members, and friends gathered for Kevin’s Valedictory Lecture and Reception at Blau Colloquium in the U-M Ross School of Business.

Kevin is a prolific public speaker and editor or author of 22 books and numerous articles on various aspects of early American history, book collecting, history administration, and related topics. Kevin became director of the Clements Library in November 2008, and in 2019, the U-M Regents honored Graffagnino’s leadership by naming him the Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library.

As a leader and colleague, Kevin was generous with his time, advice, and support. He demonstrated great confidence in the staff of the Clements, and encouraged wide participation in key areas of decision-making, such as acquisitions, digitization, and new outreach programs. He pushed staff to think ahead and envision the role of the archives in a digitized world, challenging us to come up with “the next big thing.” His door was always open for large questions and small. He showed an active interest in staff career goals and tirelessly promoted opportunities for advancement. And he never gave up hoping that library salaries would rise to the level of the U-M football coaching staff. If these recollections were not enough to endear him in memory, every day we have the great pleasure of working in the beautifully renovated building he worked so hard to bring into being.

We wish Kevin and his wife Leslie joy in their retirement!

Above: Kevin is pictured with co-editors Terese Austin and Sara Quashnie, and designer Mike Savitski, who together produced the Clements’ latest publication Americana is a Creed: Notable Twentieth-Century Collectors, Dealers, and Curators (2019). Guests at the Valedictory Lecture were treated to complimentary copies of the new book.

J. Kevin Graffagnino Clements Library Endowed Fund – Contributors to date

Virginia Adams

John Adler

Nick Aretakis

Charles & Shelley Baker

Anne Bennington-Helber

Robert Hunt Berry

John Blew

Judith & Howard Christie

Arthur Cohn

Shneen & Brad Coldiron

Barbara Comai

Joseph Constance

Richard & Deanna Dorner

Brian & Candi Dunnigan

Charles Eisendrath

Steve Finer

David Graffagnino

Margaret Harrington

Dorothy Hurt

Sally Kennedy

Raymond & Cynthia Kepner

Kenneth Kramer

David Lesser

Bruce Lisman

Richard & Mary Jo Marsh

Charlotte Maxson

Robert Mello

Donald Mott

Cindy & Peter Motzenbecker

H. Nicholas Muller

Janet L. Parker

William Parkinson

James & Judy Pizzagalli

Wally & Barbara Prince

Lin & Tucker Repess

Robert Rubin

Irina & Michael Thompson

Ira Unschuld

Michael Vinson

W. Bradley Willard, Jr.

Doug Aikenhead & Tracy Gallup

J. Kevin Graffagnino & Leslie Hasker

Benjamin & Bonnie Upton

Frederick S. Upton Foundation

Other Gifts Made in Kevin’s Honor

William & Cassandra Earle

Martha Jones & Jean Hebrand

Bradley & Karen Thompson

Leonard & Jean Walle

Announcements — Winter/Spring 2020

David P. Harris (1925-2019)

Longtime friend and donor to the Clements Library David P. Harris passed away peacefully on August 19, 2019, in Washington, D.C. For over a decade, Dr. Harris shared with us his kindness, conversation, knowledge, wit, and extraordinary manuscript projects. He compiled groups of handwritten letters, documents, logbooks, and other items; meticulously transcribed and annotated them; wrote well-researched introductory essays; and gave them to the Clements. The hundreds of manuscripts comprising the David P. Harris Collection largely focus on the Navy and Army in the early Republic, everyday sailors, and the War of 1812.

Robert N. Gordon (1953-2019)

On December 14, 2019, Clements Library Associates Board Member Robert N. Gordon of New York City passed away. From 2010-2016, Gordon served on the Clements’ Committee of Management and he remained on the Board until his death. Bob enjoyed the special capacity to channel his prodigious memory and gift for financial detail from one rarified world ‒ that of the finance of arbitrage ‒ to the even more rarified world of scientific instruments and maps. His enthusiastic support of the collecting, preserving, and making accessible the scientific contributions of earlier times made him a friend not only of the Clements but of our sister library, the John Carter Brown, where he served as a Trustee, and the Adler Planetarium in Chicago, whose valuable collection he also helped to enrich.

Margaret Winkelman (1924-2019)

Margaret “Peggy” Winkelman of West Bloomfield, Michigan, passed away on May 14, 2019, at the age of 95. She served on the Clements Library Associates Board from 1996-2014 and was part of the Honorary Board of Governors until her death. Peggy and her late husband, Stanley J. Winkelman, were collectors of art and supporters of racial integration and equality. They were leaders in the Jewish community and in efforts to improve race relations in Detroit. In addition to her years of service and support, the Clements Library will continue to treasure a 1920s Isfahan rug donated by Winkelman in memory of her late husband and her longtime companion, the late Robert A. Krause.

Exhibitions

The Best of the West: Western Americana at the Clements Library – Exhibition open Fridays at the William L. Clements Library, 10:00am to 4:00pm, through April 24, 2020.

Inspired by the work of scholar and antiquarian book dealer William S. Reese (1955-2018), this exhibition of 45 printed rarities highlights western Americana in the Clements Library collections. Featuring narratives of travel, settlement, and Native American relations, and including works in Spanish, German, and French, the selections represent some of the rarest and most significant 18th- and 19th-century sources on the American West.

Americana Sampler: Selections from the U-M William L. Clements Library – Exhibition open at the Rogel Cancer Center-Gifts of Art Gallery (Connector Alcove, Level 2, 1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor) Monday-Friday 8:00am to 5:00pm, through December 31, 2020.

Collection highlights in facsimile include handsome original artwork, compelling manuscripts, and printed resources with geographical connections spanning from the Caribbean to the Great Lakes.

2019 Faith and Stephen Brown Fellow – David Hsiung

Dr. Hsiung, a U-M History PhD graduate and professor at Juniata College, speaks about his fellowship research project “Environmental History and Military Metabolism in the War of Independence” in October 2019.

Throughout the past year, the Clements hosted lunchtime brown bag talks by some of our visiting research fellows. Eight fellows presented public talks in 2019 and three fellows authored guest posts about their research for the Clements Library Chronicles blog (clements.umich.edu/about/blog).

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Mark S. Schlissel, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Candace Dufek, William G. Earle, Charles R. Eisendrath, Paul Ganson, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Martha S. Jones, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, Thomas C. Liebman, Richard C. Marsh, Janet Mueller, Drew Peslar,

Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Martha R. Seger, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Thomas Kingsley, Philip P. Mason,

Joanna Schoff.

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Tracy Payovich, Designer, [email protected]

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Shauna Ryder Diggs, Grosse Pointe; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Mark S. Schlissel, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.