No. 55 (Winter/Spring 2022)

Manifestations of Faith

In April 1815, a Presbyterian minister named William Dickey who lived in Salem, Kentucky, received an exciting delivery. Salem is located at the confluence of the Cumberland and Ohio Rivers, and had been settled by westering migrants from Salem, North Carolina, only fifteen years before. Located near the border of what was then Illinois Territory, Salem was a tiny backcountry settlement, far removed from any centers of publication. Yet Dickey was waiting for books. A lot of books.

Rev. Dickey and his flock were the beneficiaries of the work of Samuel Mills and of charitable organizations dedicated to the mass production of religious books. Mills was an itinerant minister who toured the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys starting churches and distributing tracts and Bibles on behalf of the American Tract Society and other groups. Rev. Dickey wrote to Mills on his receipt of the bundle of several hundred tracts, saying that he had distributed them to his parishioners: “I directed those who received them, to read them over and over, and then hand them to their neighbors. . . . Religious Tracts have been much desired by us, ever since we heard of Societies of this kind. That so many numbers, and 6,000 of each, should be printed for gratuitous distribution, astonishes our people. They say, It is the Lord’s doing, and marvellous in our eyes.”

Mills described this exchange in an account of his travels published later that same year, Report of a Missionary Tour Through that Part of the United States Which Lies West of the Allegany Mountains (Andover, 1815). This encounter, and thousands of others like it, points to a profound transformation in American book history: the achievement by Protestant evangelical groups of the dream of mass communication, of giving everybody in the United States access to the same printed message at the same time, no matter if they lived in Boston or Philadelphia or in a tiny hamlet in far western Kentucky. The consolidation of hundreds of smaller missionary and tract societies into national media monoliths—the American Bible Society, the American Tract Society, the American Sunday School Union, the Methodist Book Concern—would flood the new republic with cheap (if not free) religious books. The legacy of their work can be found in library catalogs across the United States, including that of the Clements Library.

The American Tract Society published different versions of the perennially popular religious allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress, by John Bunyan, in different languages and formats, many for low-cost distribution. This ca. 1849 volume is an exception, printed by the Society but directed toward a more affluent audience. According to an advertisement, it “well deserves the neatest style of typography—the choicest engraving and the richest binding that art can bestow.”

The metaphor of the early United States as being a “religious free market” is by now quite tired, but that does not mean that it’s entirely wrong. Compared to the countries from which most European settlers came, the American colonies and then the United States were characterized by a shocking amount of religious variety. The earliest settler colonies in North America reflected this diversity: Catholic Québec and Mexico bracketing Calvinist Massachusetts, polyglot New Amsterdam/New York, Quaker Pennsylvania, and Anglican Virginia. Alongside these various faith traditions existed the varied belief systems of Native American peoples and the many religions of West and Central Africa (including Islam) that survived the Middle Passage and evolved in multiple ways on American and Caribbean plantations. While elements of state religious requirements existed in certain colonies, as in the case of 17th-century Massachusetts, by the First Great Awakening in the mid-18th century variation and denominational division were the salient characteristics of North American religion, and these trends would only accelerate in the 19th century.

Nothing about the United States struck Alexis de Tocqueville as being quite so uniquely American on his travels in the early 1830s as what he called the “spirit of association.” The freedom to form associations around particular interests or beliefs was universal in the new nation, Tocqueville wrote: “Each new need immediately awakens the idea of association. The art of association then becomes . . . the mother science. Everyone studies it and applies it.” This quality particularly applied in the realm of religion, where small groups of like-minded believers would without restriction break away from churches and denominations to start their own. And especially for religious groups, one of the most important markers of legitimacy was having a publication program. These small printing operations functioned at the opposite end of the media spectrum from the huge cross-denominational publishing houses based in Philadelphia and New York, but they had the same goals: solidifying a body of accepted beliefs and winning converts to it. From Strangite Mormons on an island in northern Lake Michigan to Massachusetts Congregationalist missionaries in Maui to frontier Methodist circuit riders, the production and distribution of religious books and tracts often marked the first appearance of print in newly appropriated parts of the American empire.

These two streams of religious publishing—metropolitan mass media and small-scale local print production—are tributaries to the core holdings of most collections of early Americana in the country. As readers of The Quarto will know, the first book printed in what is now the United States is the 1640 Bay Psalm Book, a book of scripture used in worship services in Puritan Massachusetts. Books, pamphlets, and broadsides containing Scriptural exegesis and doctrinal disputation dominated 17th-century North American publishing, and while other genres (politics, philosophy, fiction, natural history) came into prominence, the significance of religious publishing never diminished. In the 19th-century United States, the federal government is generally considered to be the single largest producer of printed material, but its output would be dwarfed if one were to combine the production of all of the denominational and non-denominational religious publishers, not to mention the countless reform organizations dedicated to causes such as abolition and temperance that had their roots in evangelical Protestantism. As the essays in this issue will show, the Clements holds resources that enable the study of American religious experience in all its variety, from theocratic persecution of Quakers in Massachusetts in the 1660s to the eschatological sectarianism of the Millerites in the 1840s.

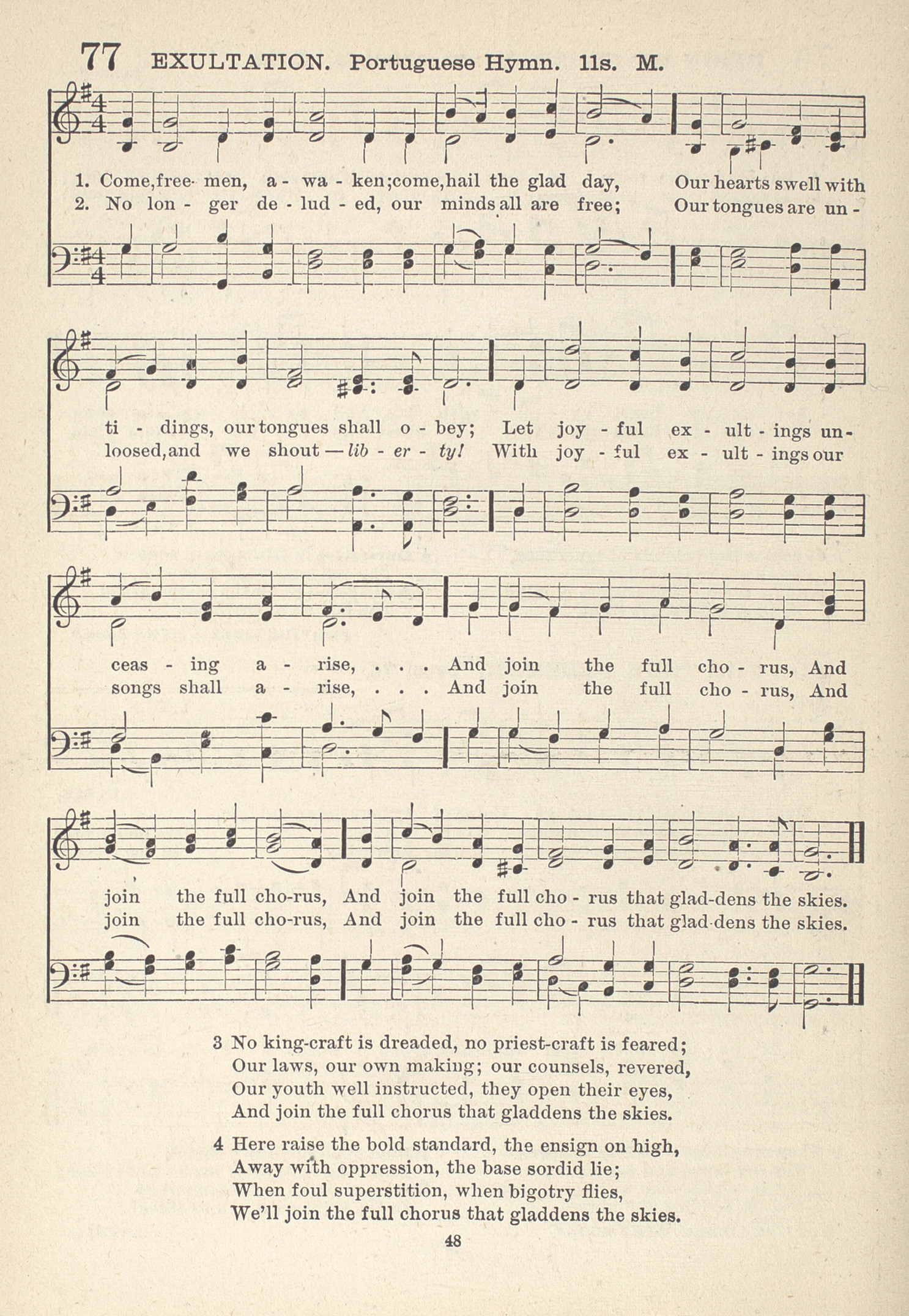

Lemuel Kelley Washburn (1846-1927) compiled the Cosmian Hymn Book (Boston, 1888) for the Freethought community, with the goal of keeping it “perfectly free from all sectarianism.” The hymns extol the virtues of nature and of freedom from all dogma with lines such as, “No king-craft is dreaded, no priest-craft is feared, our laws, our own making; our counsels, revered.”

To be a Protestant Christian in early America was to by definition be interested in print, since Protestantism of all varieties relied on the individual believer’s reading of the Bible. Further avenues for research remain to be explored in the faith traditions of people who had different levels of access to print, such as Native Americans and enslaved Africans. All too often their belief systems were targeted for destruction by Christian missionaries who circulated print to combat what they saw as heathenism. But, over time, some of these religious traditions (and their syncretic offspring) also turned to print to bind their communities together. Groups who defined themselves by their non-belief and their lack of institutional ties—agnostics, Freethinkers, and Spiritualists—also turned to print, publishing their own periodicals and, in the case of one recent Clements acquisition, even producing their own hymnal.

These groups will pose a particular challenge for historians of the 21st century. According to a 2019 report from the Pew Research Center, 26% of Americans said their religious affiliation was “nothing in particular.” These “nones” represent the fastest-growing “religious” group in the United States. But how will future scholars learn what they believe (or do not) if they don’t write about it? Agnostics in the 19th-century United States published endlessly about what they thought about religion, perhaps in an effort to push back against the overwhelming tide of religious books and pamphlets. Even in their unbelief, they associated with other unbelievers, and left records for contemporary scholars to study. One hundred years from now we may know far less about our current society’s religious or non-religious beliefs. But the rich holdings of materials at the Clements for the study of the history of American religion—“marvellous in our eyes” in their own way—can help explain how we arrived where we are now.

—Paul Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

“Don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology”: Horace, Ode I. 11

The Second Great Awakening swept the country in the 1830s and 1840s, reviving established churches and spawning fringe sects. Millennialism and the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ were some of the main motives for religious conversion. The question of exactly when was answered by Baptist minister, evangelical apocalyptic theologian, and farmer William Miller (1782-1849).

Miller’s study of the books of the Bible, particularly Daniel and the Book of Revelation, led him to believe that “prophetical scripture is very much of it communicated to us by figures and highly and richly adorned metaphors.” He believed his analysis of the chronology of events in the Old and New Testaments could determine the date of the Second Coming of Christ and the “cleansing of the sanctuary” prophesied by Daniel. Miller based his calculation on the number 2300 which he found in Daniel 8:14: “Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed” (King James Bible). Miller calculated that “the vision of Daniel begins 457 years before Christ; take from 2300, leaves 1843, after Christ, when the vision must be finished.” Miller presumed that biblical days meant years. From this equation, as well as other numerological combinations from the Bible that yielded 1843, Miller concluded that the Second Coming must occur between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844.

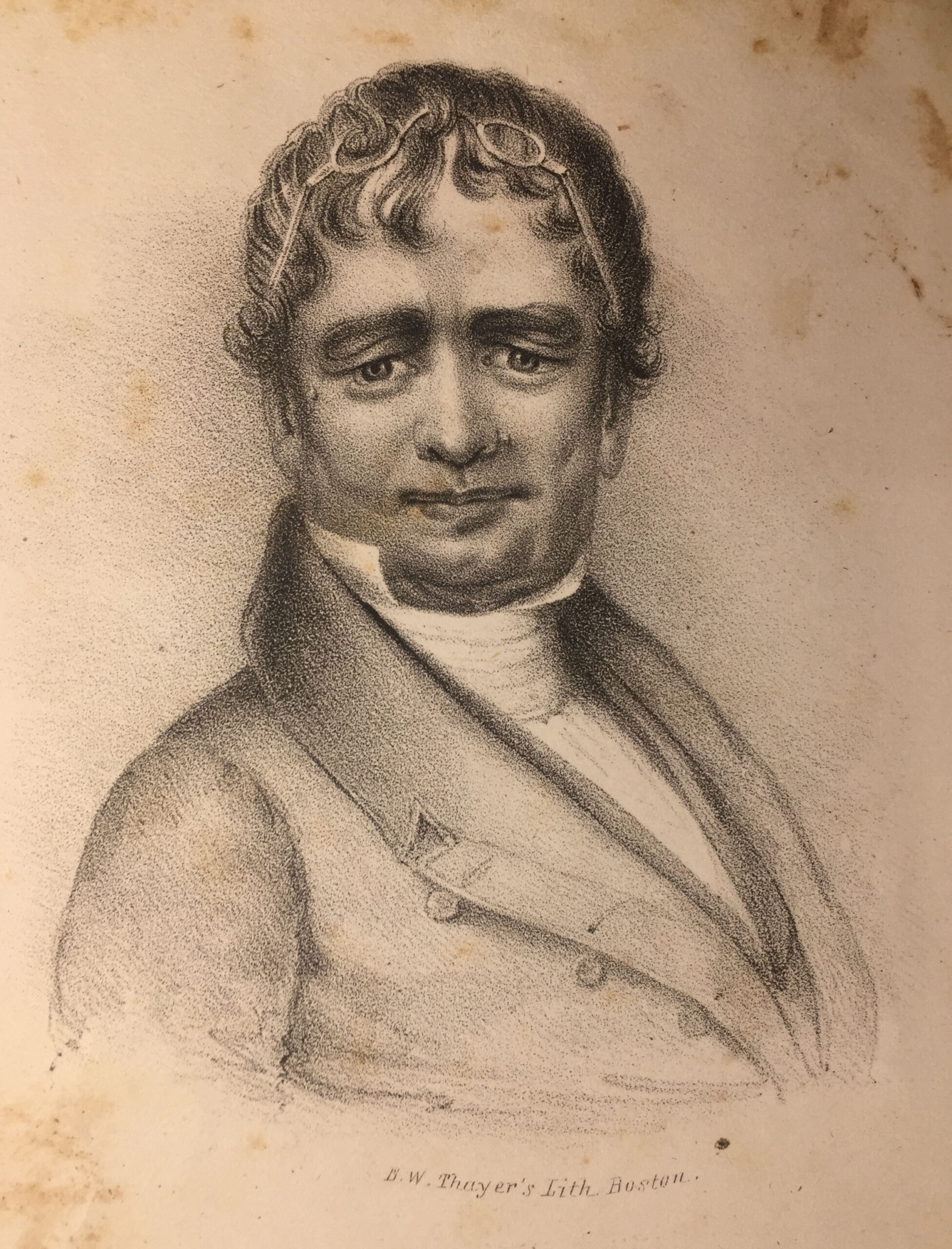

Wm. Miller. [Boston, 1841]. Lithograph by Benjamin Thayer (1814-1875), from a painting by William M. Prior (1806-1873).

Riding the wave of the Second Great Awakening, Miller gathered a following with fiery sermons on this topic. He promoted his vision to credulous audiences in churches and meeting houses across the northeast United States.

By 1839, Miller had crossed paths with Boston lithographer, publisher, and social reformer Joshua Vaughan Himes (1805–1895). Himes sat in on several of Miller’s sermons and soon became both a follower and promoter. Himes published the sermons and Millerite newspapers Signs of the Times (Boston) and Midnight Cry (New York), organized Miller’s speaking tours, and boosted Miller’s following to a peak of perhaps 50,000.

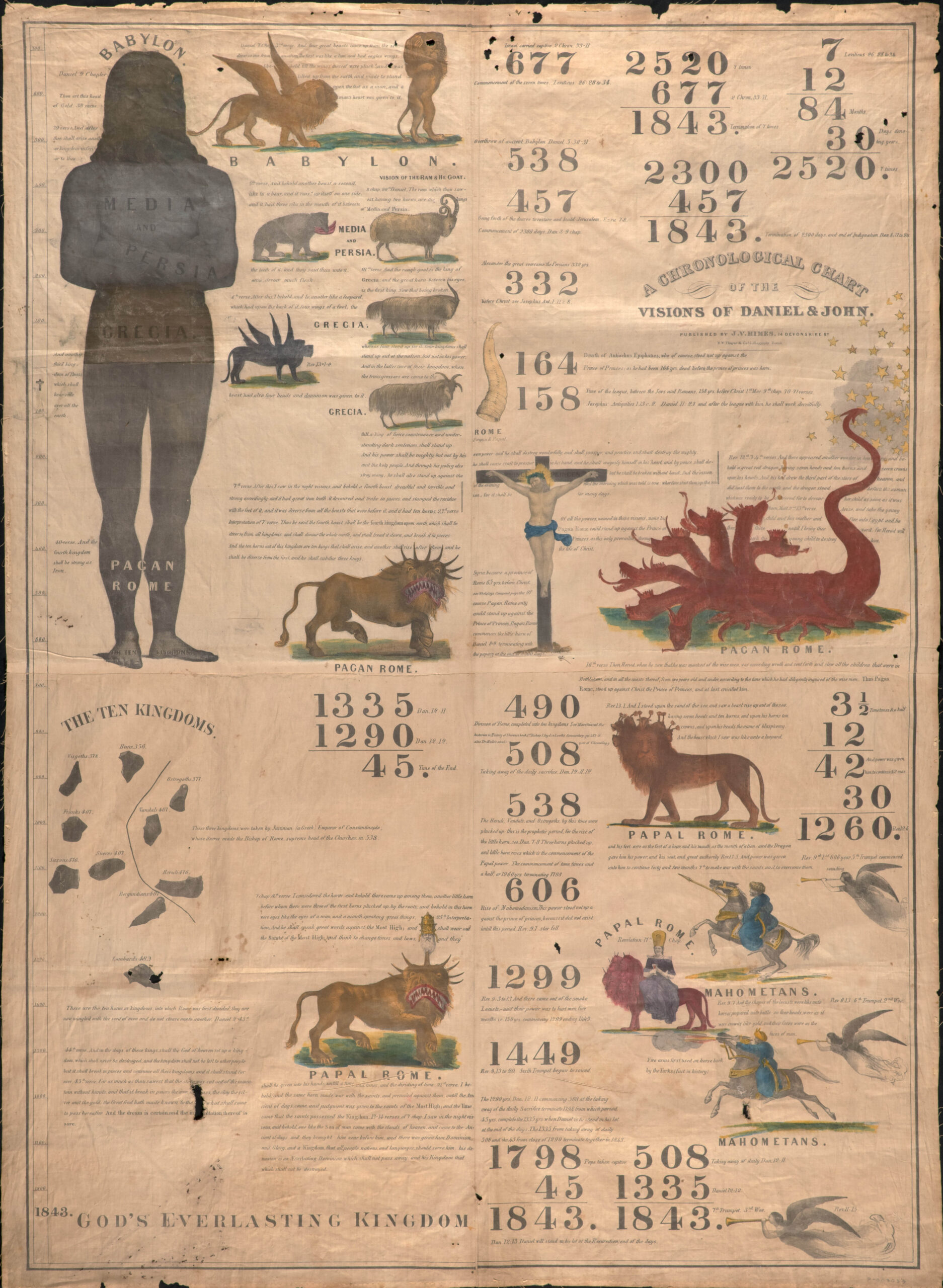

Miller’s references to the books of Daniel and Revelation and the calculations essential to Millerite belief were complicated and hard to follow. Visual aids would help explain the premise and hold attention. Himes worked with preachers Charles Fitch and Apollos Hale to design a prophetic chart that would summarize and illustrate Miller’s vision. Himes’ 1842 broadside print, Chronological Chart of the Visions of Daniel & John was produced from four lithography stones on a large 60 by 45 inch piece of fabric that could be easily folded, transported, and hung at the front of a lecture hall or from the branch of a tree outdoors.

Simultaneous with the Second Great Awakening were rapid advances in visual culture through printing technology and growing literacy. Print media became cheaper, faster, and more persuasive with sophisticated combinations of text and image. Social movements such as abolitionism leveraged this with provocative broadside prints that compelled an emotional response, such as the heart-wrenching kneeling slave image or the dramatic diagrams of slave ship interiors.

Religious pictures are often persuasive through emotional connections of a different sort. Iconic saints and holy family depictions can be deeply reassuring in their humanness. Last Judgment images threaten unending pain. The images associated with Himes’ Millerite banners are altogether something else.

A Chronological Chart of the Visions of Daniel and John ([Boston]: J. V. Himes, [1843]). Printed on fabric by Benjamin Thayer. A timeline from circa 700 to 1843 runs vertically along the left, with images of mythical beasts from Revelation and calculations based on biblical numerology. Later editions recalculated the final date to 1844, 1850, and 1853, by which time interest had waned.

Joshua Himes’ Millerite broadside combines images, numbers, texts, and timelines to generate a powerful, mysterious manifestation. Representing history from the year 700 to 1843 it addresses the unknowable future with the logic of a mathematical equation and the certainty of advancing measurable time, coupled with strange and compelling mythological metaphorical creatures, biblical figures, and monarchs from pre-history. All this, combined with the impossibility of disproving an event that has not yet occurred, made a powerful, if not fully understandable case.

As Millerites grew in numbers, their opponents grew as well, with refutations such as Abel Tompkins’ self-published Miller Overthrown: Or The False Prophet Confounded. By a Cosmopolite (Boston, 1840). “This is the day of strange things. We have phrenology, animal magnetism, sleeping preaching, political crisises [sic], and the end of the world. . . . science is always followed by her shadow, which some mistake for the substance. The same may be said of religion. Many deceivers have crept under the sacred mantle of religion, and William Miller is one of them.” A defensive Miller struck back. “My opponents have been in the habit too of spreading false reports, in order to destroy the influence of what they cannot refute. They have published my death in public papers . . . that I had altered my calculation of prophetic time a hundred years. . . . that I would not gamble away my little home. . . . that I built a stone-wall instead of a rail-fence on my farm.” Rationalists, Deists and Universalists received Miller’s scorn “In every place that this subject has been judiciously preached, [they] have been made by the power of the Spirit to see and feel their danger. . . . I beg of you to lay aside your prejudice, examine this subject candidly and carefully for yourselves. Your belief or unbelief will not effect the truth.”

Miller’s inconstant predictions provided grist for the satirist’s mill, as in this “Comedy in five acts,” the Millerite Humbug; or the Raising of the Wind!! (Boston, 1845). The pseudonymous author, Asmodeus, was “induced to offer to the public the following piece, from a conviction that many have been deluded and finally ruined by the popular frenzy . . . and if possible, expose the wickedness of those who have imposed upon the credulity and property of their fellow man.”

Miller’s deadline for the apocalypse (shifting several times as it passed) came and went, marking not The End, but the beginning of the phase known now as The Great Disappointment. The disappointment was especially profound for those who had sold their possessions, down to their shoes, in expectation of never walking on Earth again.

Scorn, criticism, and outright violence erupted as Millerite congregations turned against themselves. Many theories came forth as to what happened—the date should have been based on the Karaite Jewish calendar and not the Rabbinic calendar; the appearance of Christ was invisible to mortals; the predicted “cleansing of the sanctuary” was occurring in heaven, not on Earth; and many others. Millerite sects gathered around several main theories and carried on, but in understandably smaller numbers. Miller’s prophecies continue in varying degrees in the Adventist movement and in the theology of the Baháʼí Faith.

The absurdity of setting an exact date for The End is easy to ridicule, but at the core it was driven by ordinary people dealing with legitimate fears during times of stress and social upheaval. The decades of the 1830s and 1840s saw massive societal changes in urbanization, industrialization, financial instability, enslavement, immigration, citizenship, and other social issues in addition to emerging religious movements such as Mormonism. It is no wonder there were questions about destiny and finality. Who wouldn’t want to know when it all will end? Those with answers could draw a crowd. Miller and Himes, with mysterious mathematical formulas and dazzling diagrams, packed the house.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Material

Ode I. 11 Horace

Translated by Patrick Whalen

Do not wonder, better not to know, what end the gods hold in mind.

Whatever will become of me and you,

Leuconoe, don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology.

What will be is what we will endure:

Either more winters will follow, or Jupiter says this

Which eats away the cliffs along the Tyrrhenian Sea

Is the final winter. Be wise; strain your wine, trim your long hopes

To a point. Even as we speak envious eternity turns fugitive.

Seize the day. Believe in tomorrow but barely.

“This I will seale with my blood”: The Execution of William Leddra

Lost, missing, or nonexistent papers have a meaningful impact on the way we understand our histories. We mourn the absence of manuscripts that may have provided us with a more nuanced picture of life in and about the Americas. Many examples come to mind, but one significant loss to history is the first record book of the Massachusetts Bay Court of Assistants, dating from its establishment in 1630 through 1673. This volume contained documentation of the proceedings of the colony’s supreme judicial jurisdiction for civil and criminal cases. According to the Massachusetts Archives, the book remains missing and may well have been destroyed along with other early Massachusetts records during the American Revolution. In a best attempt to piece together this essential record, Clerks of the Massachusetts Supreme Court John Noble (1829-1909) and John Cronin (b. 1872) sought out and compiled original and copied manuscripts (from various other public and private papers) bearing on the activities of the Court of Assistants during these formative years. They were published in Records of the Court of Assistants of the Colony of the Massachusetts Bay, volumes II (1904) and III (1928). While not a continuous record of the pre-1673 court, the labors of these clerks are a lasting contribution to the source materials of the colony.

Within the missing record book were court documents produced as part of the state-sanctioned murder of Quakers William Robinson, Marmaduke Stevenson, Mary Dyer, and William Leddra/Ledra between 1659 and 1661. The Clements Library is privileged to hold the only known official manuscript copy of the court proceedings and judgment of any of these Quakers: William Leddra, who was executed in 1661. Part of the Quaker Collection, the document, dating from 1660/1661, was copied for a yet unknown official purpose by court secretary Elisha Cooke circa 1716. The provenance of this manuscript is opaque, except that it was owned in 1924 by William Oliver of Sharon, Massachusetts, who had inherited it from his father. It disappeared once again, only to reappear in a circa 1967-1970 mimeograph listing by a Texas rare bookseller as a generic 17th-century New England document. Future Clements Library Director John C. Dann, then a graduate student at the College of William and Mary, purchased the manuscript before discovering its staggering import. Dr. Dann generously donated it to the Clements Library in 1986.

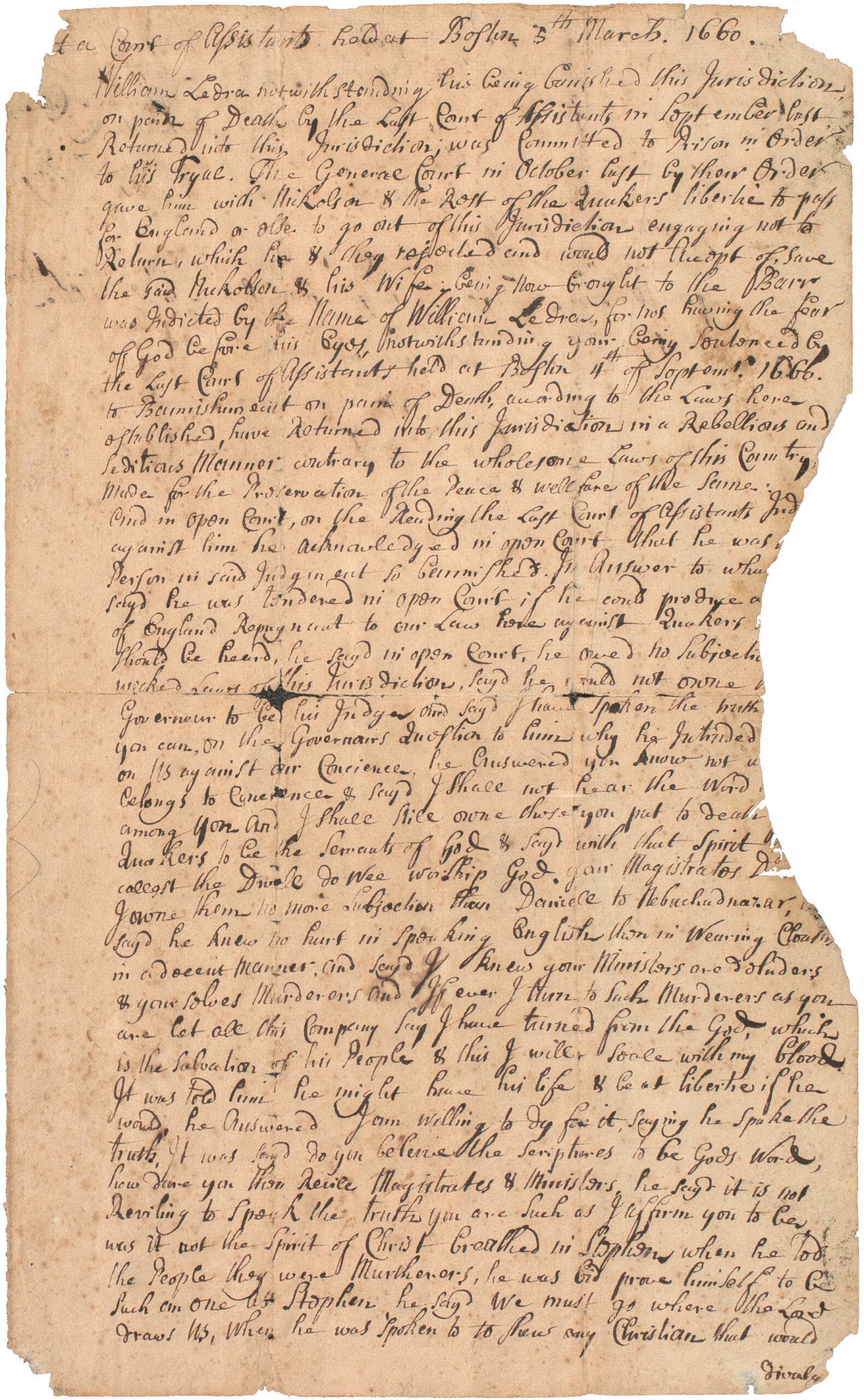

This March 5, 1660/1 legal record was copied around 1716 by Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature clerk Elisha Cooke (1678-1737). It provides scholars with the only primary source trial and sentencing document known to exist for the Quakers executed in the Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1659 and 1661.The vermin-eaten edge is a pre-20th century modification.

The story behind this document and these events lies in the push-pull between conservative and radical visions of the English Reformation. In the early 1600s under King Charles I, English Puritans found themselves in increasing opposition to what they perceived to be a resurgent Catholicism within the Church of England. The conservative Anglican Church, they believed, incorporated various religious ceremonies and practices not found within the Hebrew Bible or Christian Testament that came perilously close to Roman Catholicism. The Puritans were not separatists who sought to break away from the Anglican Church, but instead wished to purify the established church to conform to Hebrew and Christian holy writ. Especially after Charles I took the throne in 1625, hostility toward the sect blossomed, prompting many Puritans to leave the country for the freedom to practice their religion elsewhere.

In 1629, the joint-stock Massachusetts Bay Company secured a charter from Charles I to establish an economically productive colony in New England. This decree allowed shareholder colonists to elect their own executives and judiciary, provided that Massachusetts Bay laws conformed to English law; by 1631 the company became the de facto government. The fleeing Puritans were the primary settlers in the new colony and by the early 1640s, the population swelled to over 20,000. While John Winthop (1588-1649), the first governor, described it as the “City upon a Hill” (in an allusion to Matthew 5:14), the new colony did enjoy a certain level of theological freedom, allowing interpretive challenges and discussions in which alternate views might be deliberated for pursuing the Puritanical Truth.

The colony flirted with theocracy, but provided a glimmer of religious liberty to dissenters by balancing laxity and orthodoxy. Although they believed in the separation of ecclesiastical and governmental roles in the community, the Massachusetts Puritans believed the State itself was a religious body, in which their God was the ultimate lawmaker, and his laws were clearly stated in the Hebrew and Christian scripture. Their legislative and judicial mandate then, was to establish and interpret laws bestowed on the Israelites by Moses (selectively stripping out laws related to ceremony and methods of worship), and with guidance from Jesus’ words and example. Heterodox religious views that magistrates believed were disruptive to the Puritan colony were considered a critical threat to both Church and State. Religious freedom extended only to a set of acceptable, malleable boundaries established by the community leaders. And any persons whose beliefs fell outside these squishy parameters had the freedom to leave the colony.

The English colonies in America, especially Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Maryland, had statutes to prosecute religious crimes such as heresy, blasphemy, profanity, slander, the breaking of the Sabbath, and other acts. Punishments included physical, psychological, and symbolic violence. Convicted persons might be publicly shamed in the stocks, beaten, whipped, mutilated, branded, dismembered, exiled, executed, or otherwise injured. These castigations were indeed carried out. However, contrasted with the devastation of contemporary religious wars and executions of Europe, the English American colonies appear to have been more reserved in meting out punishments for these crimes.

The Quakers entered into this environment in 1656. Formed in England in the earliest years of the 1650s, the Quakers followed and follow the teaching of George Fox (1624-1691), who preached that individual persons have the spirit of their God within them—an Inward or Inner Light—and that God can speak through them without clergy as intermediaries. In the beginning, they were also an apocalyptic sect, believing that the return of Jesus Christ and the final judgment were imminent. Desperately seeking to save as many persons as possible before the end of the world, Quaker evangelists reached America with a message that they would carry quickly, loudly, and publicly to the colonies. This first generation of Quaker immigrants and missionaries were not the quietist pacifists that would form later in the 18th century. They were instead aggressively disruptive, storming into Puritan courts and churches during service, and advocating recusancy. They refused to pay legally obligated tithes, published intensely critical texts against the colony’s leadership, and proclaimed the future of the state officials in perdition. The invasion of Quakers into the colony during its formative years was met with horror. This threat was deemed a satanic effort to deceive and to undermine the religious authority that Puritans believed was vital to keeping their recently established colony intact.

In an effort to quell the influx, Puritan administrators passed laws in 1658 forbidding the heretics from landing ships in the colony and demanding that Quakers already present be taken into abusive custody and leave the jurisdiction on threat of death. Those who refused could even be enslaved. Many Quakers departed, but some, armed with their faith, returned to the colony to declare their religious message and a rejection of their persecution. William Robinson, an Englishman who was a “public witness” or missionary in Barbados, traveled to the American colonies to protest these oppressive laws. He met likeminded Londoner Marmaduke Stevenson in Rhode Island and the two traveled to Massachusetts Bay in the late spring of 1659. They were arrested and banished, but they then returned to the colony from exile and found themselves in jail once again. Meanwhile, Rhode Islander and Quaker prophet Mary Dyer, herself having been imprisoned previously in Connecticut and Massachusetts Bay, traveled to Boston to support the imprisoned Robinson and Stevenson. She, too, was arrested and banished, but also returned to minister. The three were sentenced to death on October 27, 1659. On that day, the men were executed and Mary Dyer, after standing at the hanging tree, bound, face covered, with a noose around her neck, received clemency on the condition of another banishment. While in the ensuing months other Quakers tread onto Massachusetts Bay soil, magistrates opted not to implement capital punishment. In the spring of 1660, however, Mary Dyer again followed her conscience to Boston, again received a death sentence, again stood to hang at the tree, and died there on June 1, 1660. To the Puritans, these dissenters were committing suicide by willfully defying the law. To the Quakers, they were listening to their God and pursuing their religious convictions according to their faith, even to death as martyrs.

The last person to be executed for Quaker beliefs in what is now the United States was a Cornish man named William Leddra. Like William Robinson, he followed his convictions to Barbados before sailing for Rhode Island, where he arrived in March 1658. His missionary work and meeting attendance took him to Connecticut, where he was arrested, abused, and banished. Leddra traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, where, according to Essex County Court Records, he was held on June 29, 1658, for being a stranger at “a disorderly meeting of certeyne suspected psons” on the Sabbath. He was imprisoned, starved, beaten, banished, and moved to Providence, Rhode Island. Persistent in his efforts to proselytize and to support other Massachusetts Bay Quakers, Leddra immediately returned to Boston, where he yet again found himself in jail, harmed, and banished. Then, in October 1659, the Plymouth Colony detained him for being a foreign Quaker. He remained there, fighting the “vnjust and Illegall” detention until he departed Plymouth on April 17, 1660. During this detention, he wrote a public letter to “ye Rulers: & others of ye People,” decrying the banishment/execution laws. Acting under “Necessity of conscience,” Leddra again returned to Massachusetts Bay. Magistrates promptly arrested him, locked him in chains, and fastened him to a log of wood “in an open Prison, during a very cold winter.” Finally, he was brought before Governor John Endicott and secretary Edward Rawson at the Court of Assistants in March 1661, “with his Chains and Log at his Heels.”

The Clements Library’s Massachusetts Court of Assistants document provides an account of the ensuing trial and death sentence. The court proclaimed that Leddra, “for not having the fear of God before his Eyes” despite being banished on pain of death, returned to the jurisdiction “in a Rebellious and Seditious Manner contrary to the wholesome Laws” of the colony. The court also noted the purpose of the laws, which were “made for the Preservation of the Peace & wellfare of the same.” Leddra was then challenged to find English laws in opposition to the colonies’ legislation against the Quakers. He countered by expostulating that he would neither accept the Governor as his Judge nor submit to the “wicked Laws of this Jurisdiction.” The Governor asked Leddra about his intrusion on the colonies’ “Concience.” Leddra replied that the court had no knowledge of what constitutes conscience, that those whom the court had put to death were the “Servants of God” and not, as the Puritans claimed, worshippers with a spirit “callest the Divell.” Drawing on scripture to defend himself, Leddra compared the Quakers’ resistance of the Puritans’ laws to Daniel’s (and other Israelites’) resistance to Nebuchadnezzar II—and the King’s ultimate acceptance of the Hebrew God as the highest authority. In a harsh rebuke, Leddra added that the Puritan “Ministers are deluders & yourselves Murderers”, and that he would never turn from his God in order to gain favor from murderers. With unwavering conviction, Leddra assured the court that this promise he would “seale with [his] blood.” The court gave him another opportunity to leave the colony. He refused, saying that he was “willing to dy for it, Saying he spake the truth.” Frustrated, the court (drawing on Titus 3:1) demanded to know why, if he believed scripture to be the word of their God, did he “revile Magistrates & Ministers”? Leddra declared that speaking the truth is not the same as reviling them, and he compared the Quakers’ plight with that of Stephen, who was stoned to death for preaching that Jesus was the Christ, in the Book of Acts. With no further questioning, the indictment was read, the jury convened, and the guilty verdict reached. “The Governour in the Name of the Court Pronounced Sentence agt. him That Is You William Ledra are to goe from hence to the place from when you came & from thence be carried to the place of Execution and there hang till you be dead.”

Later the same year, after William Leddra’s execution, the Massachusetts Puritans recognized the changing tides in English leadership and opinion, and revised their laws to include new tortures (in the “Whip and Cart Act”) and the continued banishment of Quakers, but to remove the death penalty as an option. Sure enough, after the restoration of Charles II as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland, he formally forbade executions for Quakerism as the capital punishment did not adhere to English Law. By 1665, King Charles also forbade the torture of Quakers. The ensuing decades saw a decrease in corporal punishment and banishment, marking an end to the legal persecution of Quakers in Massachusetts Bay.

During and after the state-sanctioned murder of Quakers for their religious beliefs, Puritans and Quakers published differing explanations and meanings for the persecutions. Writers like Cotton Mather retold the events downplaying the religious aspect and rewriting the history to focus on purely civil motivations for the hangings. Quaker writers focused on the barbarity of Massachusetts laws, the calm martyrdom of those executed, and the hypocrisy of the growing myth that New England was founded with a spirit of religious liberty. Each publication played a hand in creating narratives best suited to the contemporary needs of their religions and societies. The Clements Library holds many of the original 17th-18th century printings of these works.

The missing record book of the Massachusetts Court of Assistants would have provided historians with much-desired data and case studies on the implementation of law in the colony in a court setting. The Clements Library’s document provides details about arguments made in court, the use of specific biblical scripture in the prosecution and defense of William Leddra’s case, and the weight given in court for the combined religious and civil disruption caused by Leddra. What have we lost with the absence of court records for William Robinson, Marmaduke Stevenson, and Mary Dyer? We lost comparative examples of similar trials and sentencing, which would have enlightened us on the similarities and variances of legal argumentation used in the Quaker executions. We certainly lost the words of the first three Quaker martyrs, used for their defense and for criticisms of the legality of the persecutions. We also lost a vital female voice to counterbalance the chorus of male voices in the archives.

William Robinson, Marmaduke Stevenson, Mary Dyer, and William Leddra were not the models of quietism and peaceful martyrdom often portrayed, but they were certainly the victims of a mid-17th-century legal codification of a borderline theocratic state. In current times, the nature of religious freedom continues to foster division. Factions still argue that this freedom should only apply to believers of the same faith or to non-believers who practice in a non-disruptive and quiet manner. Religious authority and the power dynamics it seeks to perpetuate strike figuratively, legally, and violently at those who vocally argue against it. As we continue to champion diversity, equity, and inclusion, strive toward genuine religious freedom, and seek to better understand and support one another, the tragedy of William Leddra’s story can be instructive. We might remember where the legal codification of a dominant set of religious beliefs may lead us if we are not ever attentive.

—Cheney J. Schopieray

Curator of Manuscripts

These are the Great Instruments of Providence

Throughout American history, hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, floods, fires, and other dangerous naturally-occuring phenomena have randomly delivered unsparing destruction in an instant. Many of those who witnessed such tragic ordeals have found themselves leaning into their spiritual beliefs for comfort and explanation in the aftermath. The Clements Library contains many compelling resources that provide insight into religious interpretations of natural disasters.

On November 18, 1755, a 6.0 to 6.3 magnitude earthquake shook Cape Ann, Massachusetts, in what is still considered the most powerful quake to ever hit New England. While no one died, hundreds of buildings were damaged and people were left terrified. Many looked to religion to try and make sense of what had occurred, including clergyman and physician Charles Chauncey (1705-1787), who delivered a sermon, The Earth Delivered from the Curse to Which it is, at Present, Subjected (Boston, 1756), in which he categorized the quake as a stark warning from God. According to Chauncey, the purpose of natural disasters such as “tempests, famines, pestilences, earthquakes, and the like” was “to awaken the attention of a careless world, and call them to the faith, and fear, and service of the great sovereign of the universe; or to put a period to their existence here, if they are incurably turned to infidelity and wickedness . . . these are the great instruments of providence.” Chauncey pointed to the Lisbon earthquake and tsunami of 1755 (which occurred just 17 days prior to the Cape Ann quake and killed tens of thousands in Portugal, Spain, and Northwest Africa) as a possible sign of things to come if iniquity persisted.

However, not everyone was convinced that earthquakes were products of God’s righteous anger. John Winthrop (1714-1779), who at the time of the Cape Ann quake was the Hollis Professor of Mathematics and Natural History at Harvard, experienced the tremors and delivered an address, published as A Lecture on Earthquakes (Boston, 1755), regarding the incident. Approaching the subject through a more scientific lens, Winthrop believed that earthquakes were not directly caused by God’s wrath but were instead “the necessary and inevitable consequences of such laws of nature, and such powers in matter, as our globe could not well subsist without.” Winthrop believed this naturalistic perspective “ought to silence all the complaints of those who suffer either loss or terror by [earthquakes]; as well as all the objections, which men of skeptical minds have been disposed to make, upon this head, to the order of Providence. . . . For, it is plain, they may be beneficial in a thousand other ways, than we, short-sighted mortals, may pretend to guess at.”

Diary entry by Sarah Woolsey Lloyd (1719-1760) of Stamford, Connecticut, on the morning of November 18, 1755, describing the Cape Ann earthquake. At approximately 4 a.m. she was “waked by a Terrible Earthquake. This is the Second time the Lord arose to shake terribly the Earth in little more than two months besides sundry smaller shocks – what is the Lord about to Do – may we humbly Enquire when Wars and Earthquakes go before him. O Let every Heart tremble for fear of thy Judgment – Lord spare people and save thine inheritance for Jesus sake – amen – amen.”

On the evening of August 9, 1878, a tornado touched down in Wallingford, Connecticut, for around ninety seconds. By the time the twister departed, at least 34 people had been killed, over 70 wounded, and numerous structures destroyed. John B. Kendrick was tasked with writing an analysis of the tragedy, which remains the deadliest tornado in Connecticut’s history. Kendrick wrote in his History of the Wallingford Disaster (Hartford, 1878) that “Many felt strangely bewildered, and thought themselves dazed when, instead of homes, they saw utter destruction; and instead of dwellings, a plain sown with torn and twisted timber, and with debris of every kind. Strong men wept. Strewn here and there, in roads and gutters, and across the Plain, or wedged in among the debris of the wreck, were the lifeless and the maimed, helpless, and, in some cases, clothesless.” Kendrick’s survey of the Wallingford tornado’s impact is rife with disturbing details of the specific ways in which people were killed and how survivors processed what had happened. He sympathized with the mindsets of two women he interviewed who said they had been convinced Judgment Day itself had arrived, writing that “This destruction, so sudden, so complete, so fearful in every respect, coming truly like a ‘thief in the night,’ seemed to them as it would have seemed to us—the agony and passion of earth’s last hour.”

When the time came to bury the dead, the Rev. Father Slocum of New Haven delivered a powerful speech in which he implored people to take heed of the catastrophe as irrefutable confirmation of God’s fury. According to Kendrick, Rev. Slocum stated that God had allowed the tornado to wreak its deadly havoc in order to make it crystal clear that “no matter where a man’s lot is cast he must die,” and that anyone who might doubt the severity of God’s mysterious wrath should “Come here and see these corpses, and then say that He is not a terrible God, if you can.” Rather than allow such events to dampen one’s faith, Rev. Slocum instead encouraged his listeners to recognize the fearsome powers at God’s disposal and urged them to continue to “try and live according to the precepts of the divine commands, so that when we are called upon to die we shall go without fear, but with a conscience prepared for His judgement.”

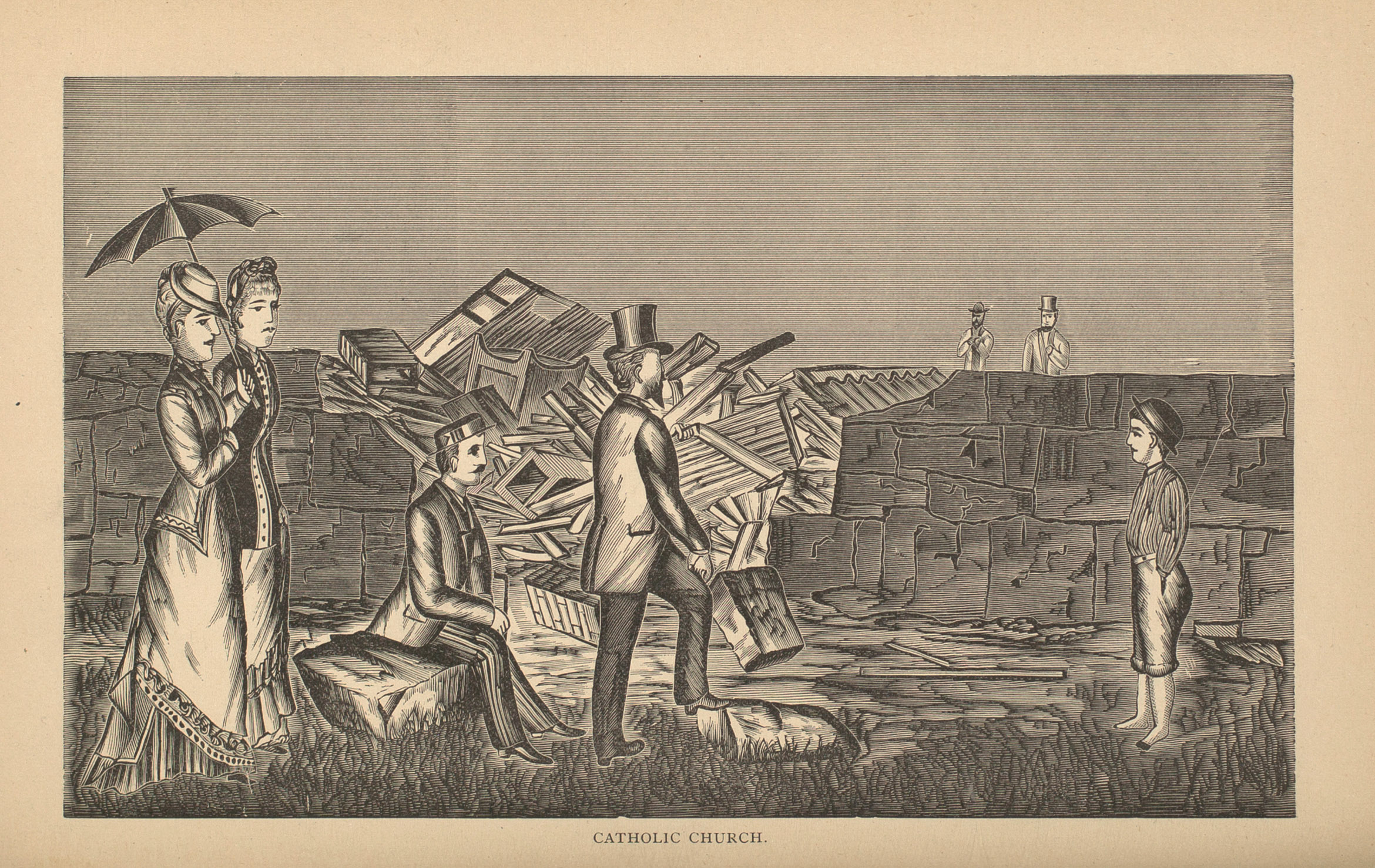

Kendrick also recorded one darkly amusing anecdote that hints at cross-denominational rivalries. Among the 34 people who lost their lives, all but one were of the Catholic faith and predominantly of Irish heritage. A deacon who visited Wallingford the day after the tornado was intrigued by this statistic. After striking up a conversation with an injured survivor named Pat Cline, the deacon smugly asked, “My poor fellow, how do you account for the fact that none but Catholics were killed yesterday?” To which Cline replied, “Sure and it’s aisy enough accountin’ for that; the Catholics are ready to die any minute, but your folks ain’t good enough to go suddint like.”

A wood engraving from John Kendrick’s History of the Wallingford Disaster (Hartford, 1878) shows the ruins of a Catholic church that was leveled by the powerful tornado of 1878.

The Galveston Hurricane of 1900 remains the deadliest natural disaster in the history of the United States. With fatalities estimated between 6,000 and 12,000 and nearly $35 million worth of damage, it is nigh impossible to fathom the scale of such suffering. On the night of September 8, 1900, the city of Galveston, Texas, was devoured by the ocean as a Category 4 hurricane brought a storm surge that rapidly inundated the city. Paul Lester’s The True Story of the Galveston Flood (Philadelphia, 1900) described the hellish scenes in extensive detail. According to Lester, dead bodies were found almost everywhere in the following days, including many that were buried under huge piles of debris. One search party even located a man who was found “on his knees, his eyes were uplifted, and his clasped hands were extended as in prayer. It was evident that the man had been praying when he was struck and instantly killed.”

In the days and weeks following the hurricane, there were many reported incidents of traumatized survivors experiencing fits of insanity and attempting suicide. Lester noted that mental health issues began “developing among the sufferers at a terrible rate. It is estimated by the medical authorities that there are 500 deranged men and women who should be in asylums, and the number is increasing. . . . Mentally unbalanced by the suddenness and horror of their losses, men and women meet on the streets and compare their losses and then laugh the laugh of insanity as a newcomer joins the group and tells possibly of a loss greater than that of the others. Their laughter is something to chill the blood in the veins of the strongest men.” Amidst such agonizing chaos it is no surprise that there were many who “in their frenzy blaspheme[d] their God for not preventing such a catastrophe.”

Spiritual leaders shouldered the arduous task of restoring people’s shattered faith. According to Lester, the Rev. Dr. Russell H. Conwell (1843-1925) attributed the disaster to “the working of God’s immutable laws, and declared that the calamity in its end was for the good of all things.” Rev. Conwell readily admitted the annihilation of so many decent God-fearing men, women, and children for seemingly no good reason terrified him, yet still he clung to the belief that “the destruction of that city so suddenly was God’s doing, and consequently it must be for good. It was His doing and what He does is right. The hurricane was the necessary outcome of all the working laws of God. . . . We can not understand that; we sit back in our heart’s darkness and say, ‘God is wrong; He is not governing the universe.’”

As horrific as the Galveston hurricane was, the brutality of the storm was matched in equal measure by the charitable responses of many people and organizations that helped the battered city rebuild. Lester’s account includes quotes from Chicago-based ministers, such as Rev. Samuel Fallows (1835-1922), who felt a strong kinship with Galvestonians after having experienced their own apocalyptic disaster in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Rev. Fallows defiantly proclaimed in one inspiring sermon that the “lesson of self-help which this calamity teaches will not be lost. God intended man to conquer nature, to bind its forces, to ride triumphantly on its seemingly resistless energies. Galveston must not be blotted out. It must rise to newness of life. Like our own Chicago, it must be rebuilt on a higher level. It must rear its structures so that the angriest waves shall not dash them to pieces. Another lesson of American pluck and energy will thus be learned by mankind.”

—Jakob Dopp

Graphics Division Cataloger

Recent Acquisitions — Winter-Spring 2022

Book Division

This newly-acquired volume includes wonderful leaves of publishers’ advertisements in the back of the book. The publisher claims that he has a large collection of books, over 50,000 in stock, on a wide variety of subject matter that are available for purchase, including many scarce and valuable books. He also advertises his paper mill, which is able to supply paper of any quality. In addition, he offers cash for linen, cotton rags, wholesale cloth, and junk. Altogether, this provides an interesting glimpse into the economics of bookselling and papermaking at a particular moment in New York history. “He does bookbinding with neatness and reasonable prices and also job printing of all kinds, executed at moderate rates”—an all-in-one business model. A notable feature of this particular copy is that it is bound in contemporary paper over scale board with a hand-sewn leather overcover. It includes ownership inscriptions from Jacob and Lydia Garretson, and then “a present to Phebe Angeline Walker 1851” in the back of the book, with cloth flowers tucked into the binding, a lovely example of repair and continued use of the book long after it was printed.

The Carrier Dove, a Spiritualist newspaper published in San Francisco and edited by two women, Elizabeth Lowe Watson (1843-1927) and Julia Schlesinger (1847-1929).

A publication with a feminist perspective, the Carrier Dove adds to our growing materials on Spiritualism. It includes articles on topics such as women in journalism, reporting that “Progressive newspaper makers are fast realizing the fact that some of the ablest and most earnest workers in journalism are women. A few years ago, a woman novelist was regarded as something of a curiosity and a woman journalist as little less than a monstrosity. Time has abundantly demonstrated the fact that a woman can earn her living with her pen and still preserve her womanliness and she can put a snap, a go, a delicacy in her work which few men can imitate.” There is more reading to be done in this volume on many Spiritualist and feminist topics. The Clements also recently acquired a volume of biographies of Spiritualists written and edited by Julia Schlesinger.

Manuscripts Division

Le Maire Family Papers, 1785-1854. 339 Manuscripts.

This collection contains upwards of 300 letters and documents pertinent to the Haitian Revolution and will serve as a support and expansion of our representation of the conflict and its aftermath. The Le Maire family of Dunkirk on the northern coastline of France owned a coffee and cocoa plantation near Jérémie, St. Domingue (Haiti), and the collection includes rich correspondence during the two years leading up to the 1791 uprising of enslaved persons, a few letters during the conflict, and letters from France discussing the conclusion of the conflict. These papers are a striking addition to our West Indies collections particularly for the documentation of the Haitian Revolution from a French planter’s perspective. Following the revolution, the French government negotiated to recognize the new Haitian government, but in return demanded that the Haitians pay reparations for lost property, including the property embodied in formerly enslaved persons. Paperwork regarding these reparations forms the core of the Le Maire Family Papers.

Cuba Collection, 1830-1893. 68 Manuscripts and growing.

The Cuba Collection consists of recently acquired items merged with several pre-existing items from the Clements holdings. This combined collection represents our efforts toward documenting selected aspects of Cuban history within the parameters of realistic acquisition opportunities, needs of researchers, and teaching methods. We will continue to add new materials to the collection moving forward.

The collection currently relates to aspects of the economic, racial, and political history of the island in the 19th century. It especially documents the indentured servitude of Chinese workers, as well as Cuba’s enslavement and manumission of largely African people. Other items pertain to insurrections and filibusters on the island, including pieces related to the Lopez Expedition and the Cuban independence conflicts of 1868-1878. Also present are examples of passports for the transfer of slaves from one plantation to another, insurance policies on individual enslaved persons, slave auction records, manumission documents, various examples of contracts for Chinese indentured servitude, other Chinese immigration documents and railroad labor paperwork, citizenship and death certificates, and more.

One notable item is a sewn body of 21 letters documenting military actions and plans of Cuban revolutionaries in 1870, particularly the correspondence of revolutionary Miguel de Aldama, a wealthy Cuban aristocrat who became president of the Cuban Junta in New York.

Graphics Division

[Portrait of Long Otter], by Richard Throssel.

A striking portrait of Long Otter (mis-titled Long Otto) has joined the Clements collections. Taken by Richard Throssel (1882-1933), a photographer of Native American descent, the platinum print shows Long Otter of the Crow Indians wearing a headdress topped with what appears to be a golden eagle. This exciting and unusual photograph, where both creator and subject were Native Americans, will be added to the Richard Pohrt, Jr. Collection of Native American Photography.

Also new to the Graphics Division are two cabinet photographs of students who attended the United States Indian Industrial Training School (known as the Haskell Indian School and currently in existence as the Haskell Indian Nations University), a boarding school for Native Americans started in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1884. The only identified individual is Robert Agosa, who was Ojibwe and whose grandfather was a tribal leader. Agosa went on to become a prominent tailor in the Traverse City area.

Map Division

Detail from Guinea propria, nec non Nigritiae vel Terrae Nigrorum maxima pars, geographis hodiernis dicta utraq . . . ([Nuremberg], 1743).

Guinea propria, nec non Nigritiae vel Terrae Nigrorum maxima pars, geographis hodiernis dicta utraq . . . [Guinea itself as well as Nigritia or the greatest part of the Land of the Blacks as told by today’s geographers…] ([Nuremberg], 1743).

The long full title in Latin and its French equivalent at the top of this highly detailed map tells us much about the sources of this depiction of the coast and interior of the West African region now known as the sub-Sahara. Many notes in Latin populate this map of northwest Africa and its coastline, providing a wealth of detail about trade opportunities, local people, and geographic features. A lettering system of F. H. A. or D. is used to indicate which Europeans (French, Dutch, English, or Danes) held coastal trading posts or factories, used as clearing houses for trade goods and human beings destined for transport in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. At the same time, African kingdoms which controlled the coast and the near interior are also labeled and described. A detailed and evocative illustration in the lower left describes visually the way of life of locals in Cap Mezurado (on the coast of what is now Liberia)—house, kitchen, milling works, meeting house—and the style of dress of the king and queen of Juda, on the Gold Coast in what is now Benin. These sympathetic depictions and the geography are based, according to the title, on the travels of the chevalier Des Marchais (d. 1728) in the region from 1725-27, described and published by Jean Baptise Labat (1663-1738), in Voyage du chevalier Des Marchais en Guinée (Paris, 1730) with maps by the French geographer, J.B.B. d’Anville (1697-1782). The Latin/French map was compiled from these sources by the German geographer, Johann Matthias Hase (1684-1742), who used a new projection of his own devising, and published by the Nuremberg map firm, Homann Heirs, in 1743. Thus the map represents the result of on-site observations and leaves blank what is unknown. The map is an important connection to other Clements material on the centuries-long trade in enslaved people.

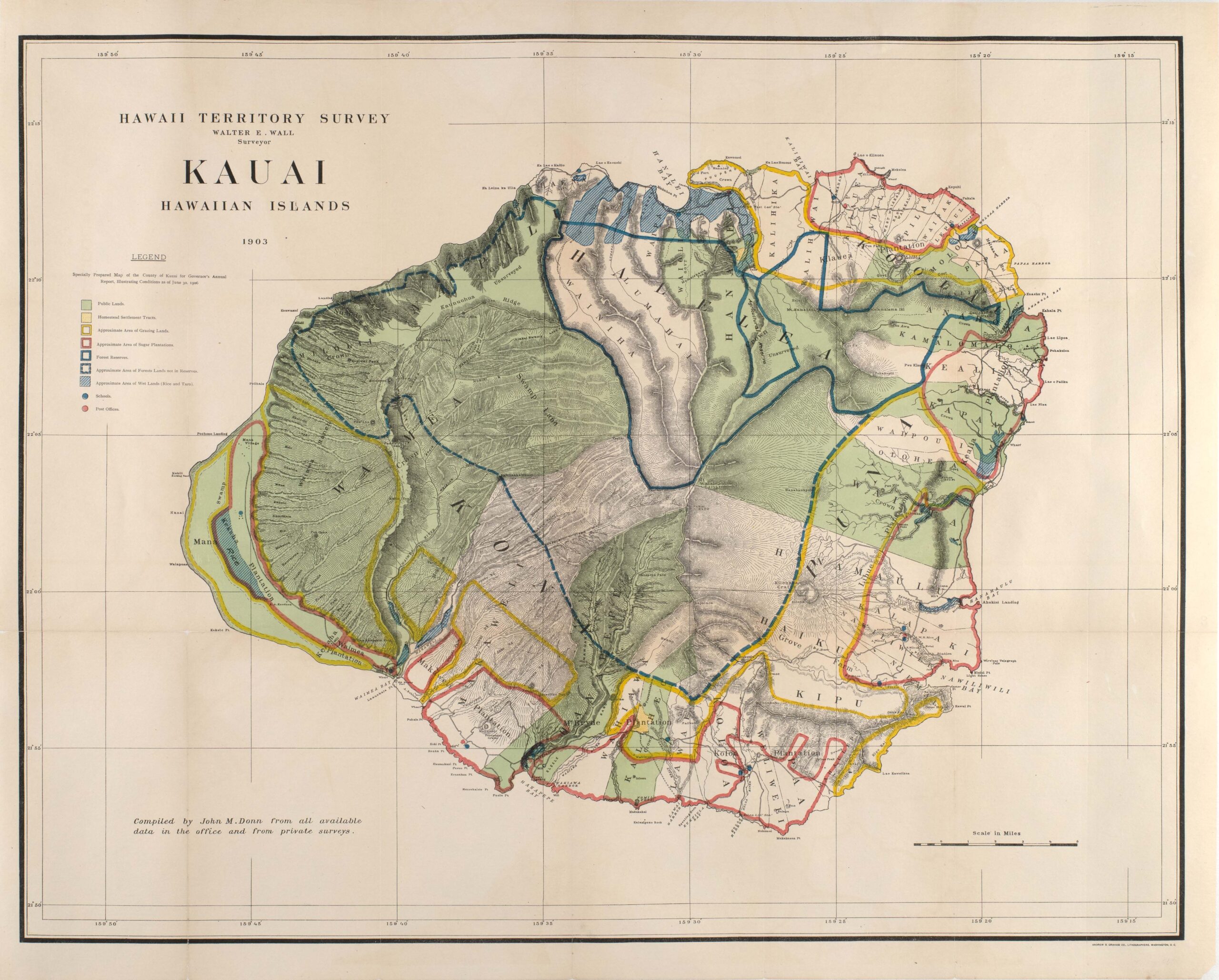

Kauai, Hawaiian Islands, by Walter E. Wall, surveyor (Washington, D.C., 1903).

This map of Kauai is one of a set of maps of the Hawaiian Islands recently acquired for the Map Division. Surveys of the Islands were begun by the Hawaiian monarchy in the 1870s. After the United States-backed overthrow of the monarchy in 1893 and annexation of the islands in 1898, new maps were issued based on these surveys, in the time-honored tradition of an imperial power claiming its territory. Published by the United States Department of the Interior, they focus on arable land and the exploitation of natural resources, containing information on pineapple and sugar plantations, forest lands and reserves, grazing lands and wetlands, public lands and homestead settlement plots. Although the Clements collections are not currently strong in Hawaiian material, the acquisition of these beautiful maps may spark reflection and conversation on the commercially-driven land grab that evolved into statehood for Hawaii in 1959. The maps now at the Clements include Niihau, Maui, Lanai, Kauai, and Molokai; the set lacks Oahu and the Big Island, which we continue to seek.

Director’s Choice

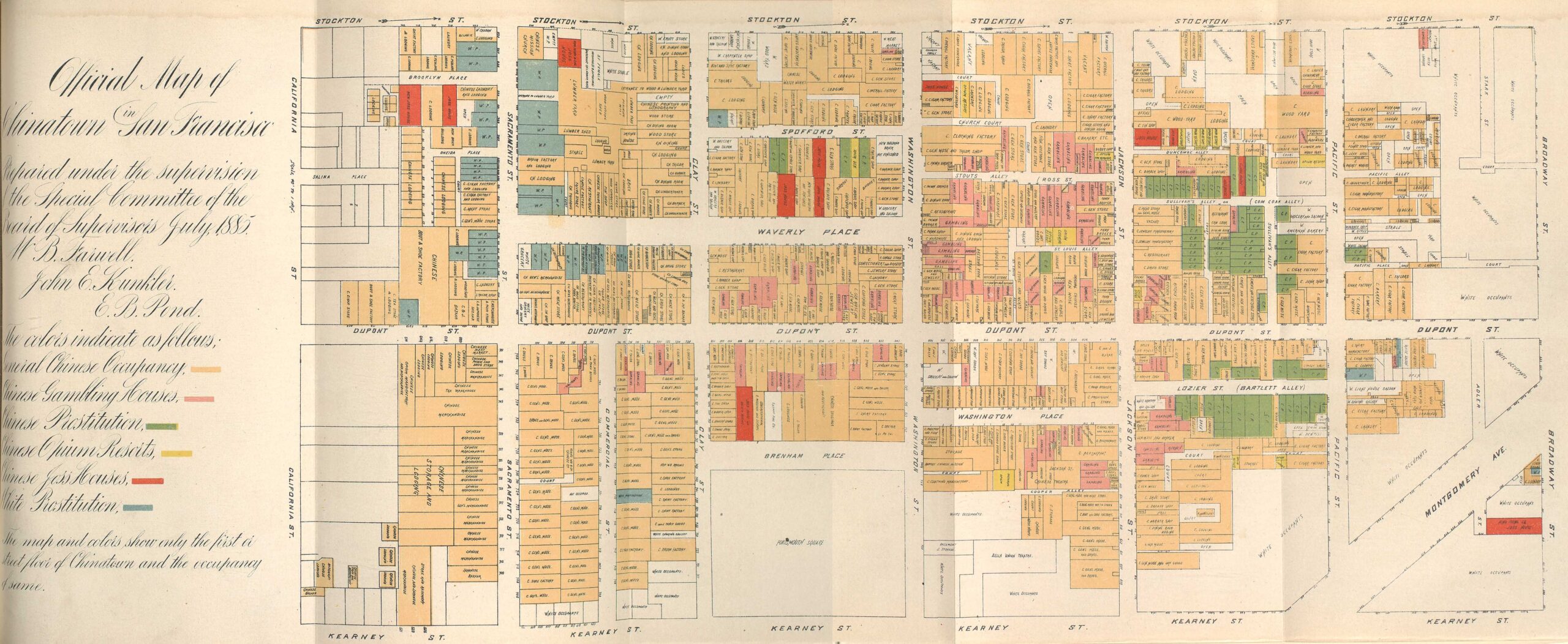

Official Map of Chinatown in San Francisco (San Francisco, 1884-85).

Paul Erickson has an abiding interest in adding to the Clements Library’s strengths in 19th century crimes and associated material. To broaden the collection, he recently acquired an interesting new item on the subject of local crime. This map of Chinatown in San Francisco from a municipal report of 1884-85 depicts the area as a vice district, marking houses of prostitution, gambling houses, and opium dens. Produced two years after the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, this is a fascinating cartographic example of criminalizing race, by presenting the densest settlement of Chinese immigrants in San Francisco as the epicenter of criminal activity, even though crime was taking place all over the city. It is a great example of how a majority white community defined crime racially and how it used perceived differences to create boundaries defining communities.

Another crime-related addition is a photograph from a notorious serial murder case at the turn of the 20th century. This is a real photo postcard from the investigation taking place on the Indiana farm of Belle Gunness (1859-1908?), a Norwegian immigrant who settled in Illinois and then Indiana. Gunness’ victims included several children who died under mysterious circumstances in addition to at least 14 men lured to her farm in answer to an advertisement for a husband, instead being robbed and bludgeoned.

Trial of A.B. Hillmantle, (Hartman, Arkansas, [ca. 1880]).

Ephemeral items reflect passing cultural obsessions in creative ways, and this broadside uses the trope of crime and punishment to advertise the dry goods store of A.B. Hillmantle, who was “convicted” of selling clothes at low prices. Each juror found him guilty on all counts of providing quality goods at reasonable prices and having the widest selection of clothes available in Hartman, Arkansas. Due to the thinness of the paper, it’s a miracle it has survived, but it now has a safe resting place at the Clements.

Developments — Winter/Spring 2022

I entered the meeting space with curiosity and took in the scene before me. Paper worksheets, clipboards, and pencils greeted me on the first table, and there were a dozen books laid out on another three tables. The books varied greatly, but I was drawn first to a thick volume with a worn leather cover. I recognized it as one of the first objects I encountered at the Clements Library, Mamusse Wunnestupanatamwe Up-Biblum God, also known as the Eliot Indian Bible.

Puritan missionary John Eliot produced this Bible in 1663, translating all 66 books into the indigenous Massachusett language. He felt so strongly about his work and the power of the Bible that he developed a written alphabet for the language. Although there is no evidence to suggest that he was successful in his missionary efforts, this record of Massachusett remains a testament to his undertaking.

Sharing the materials at the Clements is core to our mission and we strive to find a variety of ways to do this, including university classes, in-person research, and digitization. As a staff member hired specifically for outreach, Maggie plays a key role in making the Clements collections available to a wider audience. Sharing, after all, is an action that happens between two or more people.

We are raising money to bolster the staff at the Clements Library. The NEH grant to digitize the Thomas Gage papers provided us with the salaries for three digitization technicians; two for three years and one for two years. Recent grants from the Delmas Foundation and the Upton Foundation supplied seed money for a two-year graphics cataloging position. These are good starting points, but we must do more.

I watched as students began to arrive. Maggie introduced the materials and provided each student with a worksheet and a pencil. They struggled to read Angelina Grimké’s beautiful cursive notations in the margins of her Bible and mused over the tone set by the various religious illustrations. They asked questions, made observations, and discussed how amazing it is that they can look at volumes that are so old.

I felt rejuvenated and remembered exactly why I love my job as a fundraiser: because of the potential to connect people, build community, and inspire learning. In order for the Clements to operate in the welcoming, inclusive, generous way we dream about, we will need a holistic plan to increase our staff levels. The Clements Library needs your help to build a future-thinking course of action. Please reach out to discuss ideas, ask questions, and to offer your philanthropy. I appreciate all that you do to support the Clements Library.

—Angela Oonk

Director of Development

Announcements — Winter/Spring 2022

Staff News

The Clements Library welcomes new staff members Meg Bossio and Maggie Vanderford. As a reading room supervisor, Meg is now part of the team providing services to our onsite researchers. In a newly created position, Maggie joins the Clements as Librarian for Instruction and Engagement. Maggie’s mission is to coordinate the teaching program by working closely with university faculty and staff to integrate our collections into curricula.

New Joyce Bonk Graduate Student Assistant Claire Danna joins the staff for the next two years while she attends the University of Michigan’s School of Information. Claire is currently working to digitize real photo postcards from the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography and is participating in a new crowdsourcing program on Zooniverse.

As part of the Clements Library’s grant-funded initiative to digitize the Thomas Gage Papers, we welcome digitization technicians Tulin Babbitt, Katrina Shafer, and Michelle Varteresian. Their skills in scanning and providing metadata will help usher one of our largest and most-used collections into the online environment.

In Memory

Distinguished historian and archivist Philip P. Mason, a member of the Honorary Board of Governors of the Clements Library Associates, passed away on May 6, 2021.

Rare 1761 Manuscript Plan of Detroit Acquired

The Clements Library has recently promoted exciting news of a new acquisition—the “Plan of the Fort at De Troit,” hand-drawn for British officials in 1761. It becomes our earliest original manuscript plan of the fort and an inset is now our earliest pictorial view. Clements staff acted fast to secure this rare resource for its purchase cost of $42,500.

A crowdfunding campaign was quickly launched seeking help from our community and the greater public to fundraise for this important acquisition. In less than 3 weeks, donations exceeded our goal, raising a total of $43,428, fully funding the acquisition. Our sincere appreciation goes out to Tom Andison, Tom and Cheri Jepsen, George Jones, and Jim and Pam Neal for stepping up to match the first $20,000 in donations, leading the way to this important achievement. We are delighted that this plan is now available for study.

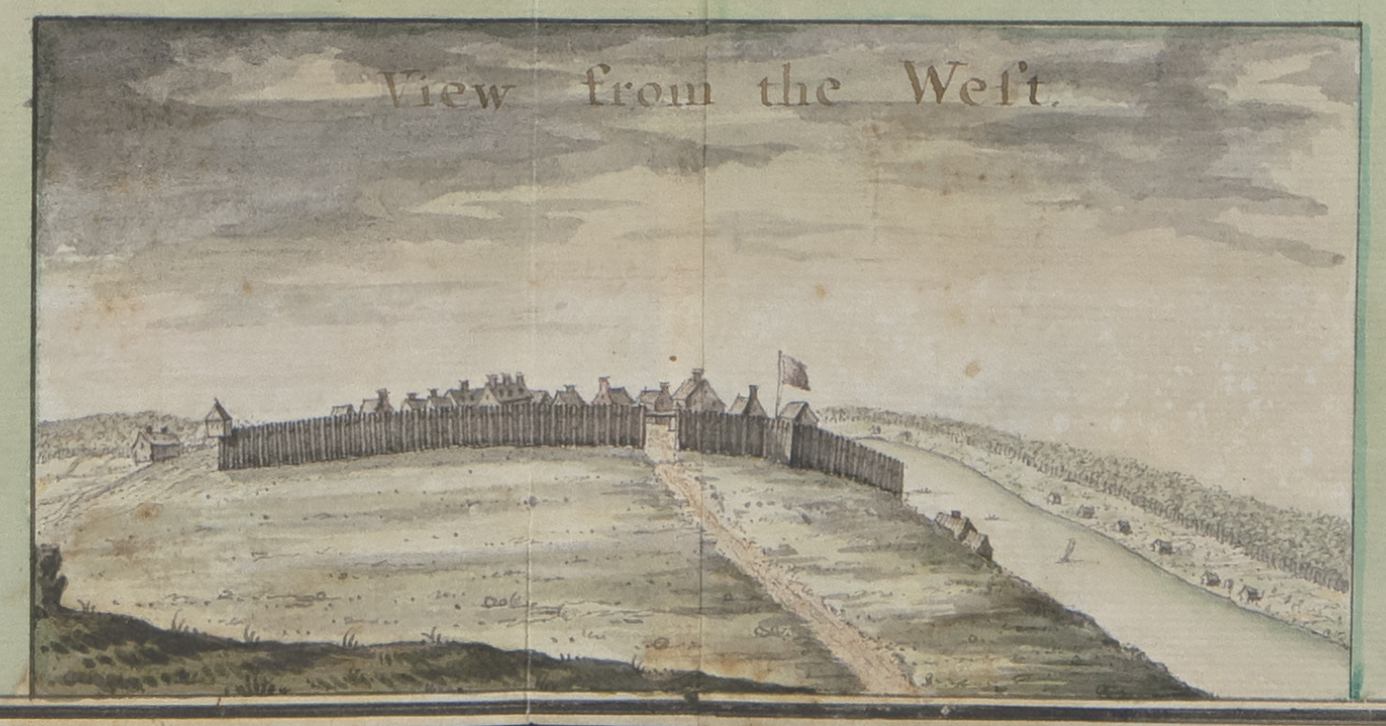

An inset illustration labeled “View from the West,” shows rooftops jutting above wooden palisade walls, sited on a gentle rise of land overlooking the river. It vividly captures what the British saw when they approached the fort for the first time to accept the French surrender just months before this map was produced.

Transatlantic Fellowship Partnership Launched

We are pleased to announce the launch of a new research funding program for 2022-2023. In partnership with the American Trust for the British Library, we will offer a Transatlantic Fellowship designed to support at least four weeks of research between the British Library and the Clements Library, with at least one week of research time at each institution. This opportunity will support researchers whose projects will benefit from the use of primary source materials in both libraries, enabling the production of exciting transatlantic scholarship.

The New Julius S. Scott III Fellowship in Caribbean & Atlantic History

In memory of the late Dr. Julius S. Scott, colleagues, friends and family have established a new fellowship to support early-career researchers traveling to use the collections of the Clements Library to conduct research in the fields of Atlantic and Caribbean history, broadly construed. Dr. Scott, who passed away in December 2021, was a Lecturer in Afroamerican and African Studies at the University of Michigan and author of the groundbreaking book The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (London, 2018). The Clements is now fundraising towards a $50,000 goal to sustain the fellowship through endowed funds.

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Mary Sue Coleman, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Kristin A. Cabral, Candace Dufek, William G. Earle, Charles R. Eisendrath, Derek J. Finley, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Troy E. Hollar, Martha S. Jones, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, James E. Laramy, Thomas C. Liebman, Richard C. Marsh, Janet Mueller, Drew Peslar, Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Peter Heydon, Chair Emeritus. Joanna Schoff.

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Tracy Payovich, Designer, [email protected]

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Sarah Hubbard, Okemos; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Mary Sue Coleman, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.