No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

Evolution of an Archive

As people who work in a rare book library, my colleagues and I are all by nature completists, which is to say that the most nerve-wracking question on our minds as we contemplate our centennial celebrations is: What if we leave something out? But we can’t tell every story of every research discovery in the library, we can’t show you every picture of every source that we love (not if you want to be able to actually lift this issue of The Quarto). What I can do, though, is point to some highlights in this wonderful issue, and to some events in the coming year, that will show how we are thinking about our centennial—as a celebration of a storied past, but also as a gateway to a new century.

Other articles in this issue highlight the work that members of the Clements Library staff have done over the previous century. Julia Miller shows how both collectors and scholars have become more interested in examining original bindings—as opposed to embellished re-bindings— of early American books, an area where we have been focusing some of our acquisitions energy. And Angela Oonk describes the crucial role that building connections with donors has made in sustaining the Clements for its first hundred years.

Everything that we do at the Clements—and everything that we plan to do—is based on our collections, and on their continued growth. And our commitment to the importance of the in-person encounter with primary sources from the American past is stronger than ever, as we emerge from the past three years where the pandemic made those encounters difficult for many researchers. Technology now permits readers on the other side of the world to see manuscripts, photographs, and books from the Clements collection as clearly as they could in the Avenir Room, and we will continue to broaden this mode of access. We will also work to make the library a more welcoming place for an increasingly diverse group of students, scholars, and other visitors. All of the changes that you see when you visit the library over the coming year are intended to help us better tell our story, to let the community at the university and beyond know what we do and what we stand for. We remain committed to preserving the materials in the Clements collection for future generations, but we are also committed to putting them to use for the generation that’s here right now. It’s going to be an exciting second century.

— Paul Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director

William L. Clements Library

“Who Knows but a Woman May One Day Preside Here”

Curators and librarians try hard to be as neutral as possible, to approach historical materials as something we’re dedicated to describing, preparing for use, and stewarding. But occasionally, something happens that just makes you plain mad.

The story that always gets my hackles up begins with Sarah Moore Grimké, a leading abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, touring the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. She was largely unimpressed with the gloomy interior, where “scarcely a ray of light penetrates it, & you have to admire it by a sort of dim twilight.” Her highlight came later, when she was invited to take a seat in the Chief Justice’s chair in the Supreme Court’s chamber. It was 1853, women couldn’t vote, they didn’t serve in the judiciary branch in basically any capacity, and the women’s rights movement was still relatively fledgling. But when Sarah sat in that chair, she “involuntarily exclaimed, ‘Who knows but a woman may one day preside here.’” She noted that her companions were “much amused,” and one man in the party, “a jovial naval officer,” kept retelling the tale to everyone they met as they proceeded through the Capitol. I can imagine the reactions. She was left admitting “that the signs of the time were rather portentous” [26 December 1853? or 2 January 1854?].

It’s a remarkable, if infuriating, story, of a prominent (if admittedly imperfect) activist being moved to look into the future and dream of possibilities. For doing so, she faced ridicule, or at the very least skepticism and disregard. The hardest part of this story for me, though, is what comes after, because the Clements Library planted its own obstacles on the far-too-long road to the recognition of Sarah Moore Grimké’s strength and foresight.

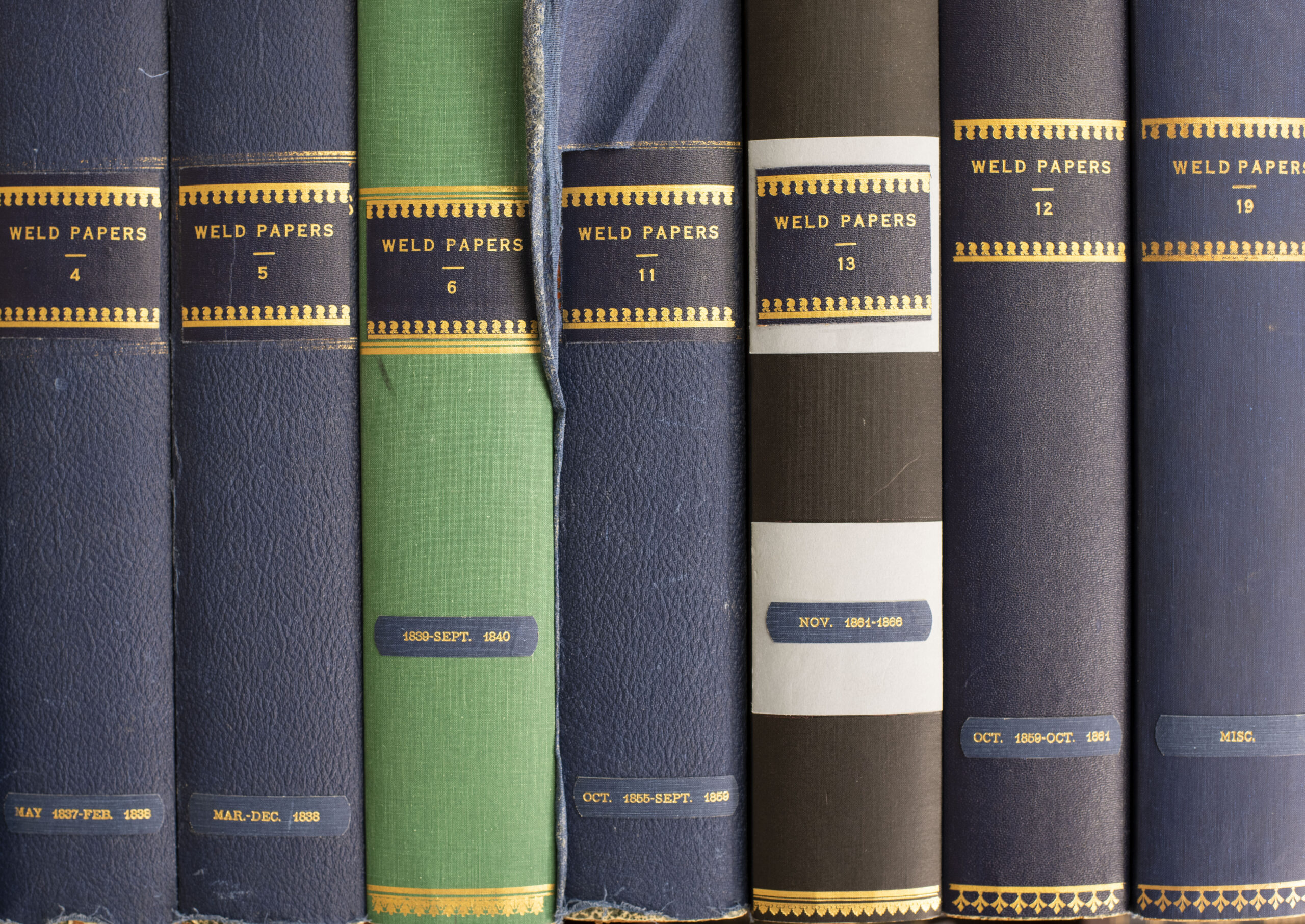

Sarah’s tale is part of a collection that originally came to the Clements with a cache of family papers in 1939, shepherded to the library by Dwight Lowell Dumond who was working at the University of Michigan as a history professor and liaised with the family’s descendants to bring the collection here. It proved to be an extraordinary, multifaceted resource that spoke of abolition networks and how families labored together against slavery; women’s activism and the complicated terrain of sex and gender in the mid-nineteenth century; temperance and nutrition movements; interracial friendships and their limitations, and much more. While hundreds of correspondents are represented, three figures really stood at its heart: Sarah Moore Grimké, her sister Angelina Emily Grimké, and Angelina’s husband, Theodore Weld. Some back of the napkin analysis suggests the original donation contained at least 500 pieces written individually or jointly by Sarah and Angelina, and some 200 letters written by Theodore. Yet when the collection was first accessioned in 1939, it was described as “Papers of Theodore Weld and Grimké sisters.” My lips purse a bit at the omission of even Sarah and Angelina’s names, and the frustration grew when reading the 1942 entry for the collection in the Guide to the Manuscript Collections in the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor, 1942). It outlines Theodore’s life story and activism in great detail but contains just one short paragraph about Angelina and Sarah, boiling down their work to one sentence, “They wrote and lectured for the antislavery cause and also for women’s rights and peace.” The boxes that housed the collection for decades were labeled simply “Weld Papers.”

A two-foot-tall stack of boxes in the Manuscripts Division Office bear outdated labels that read only “Weld Papers.”

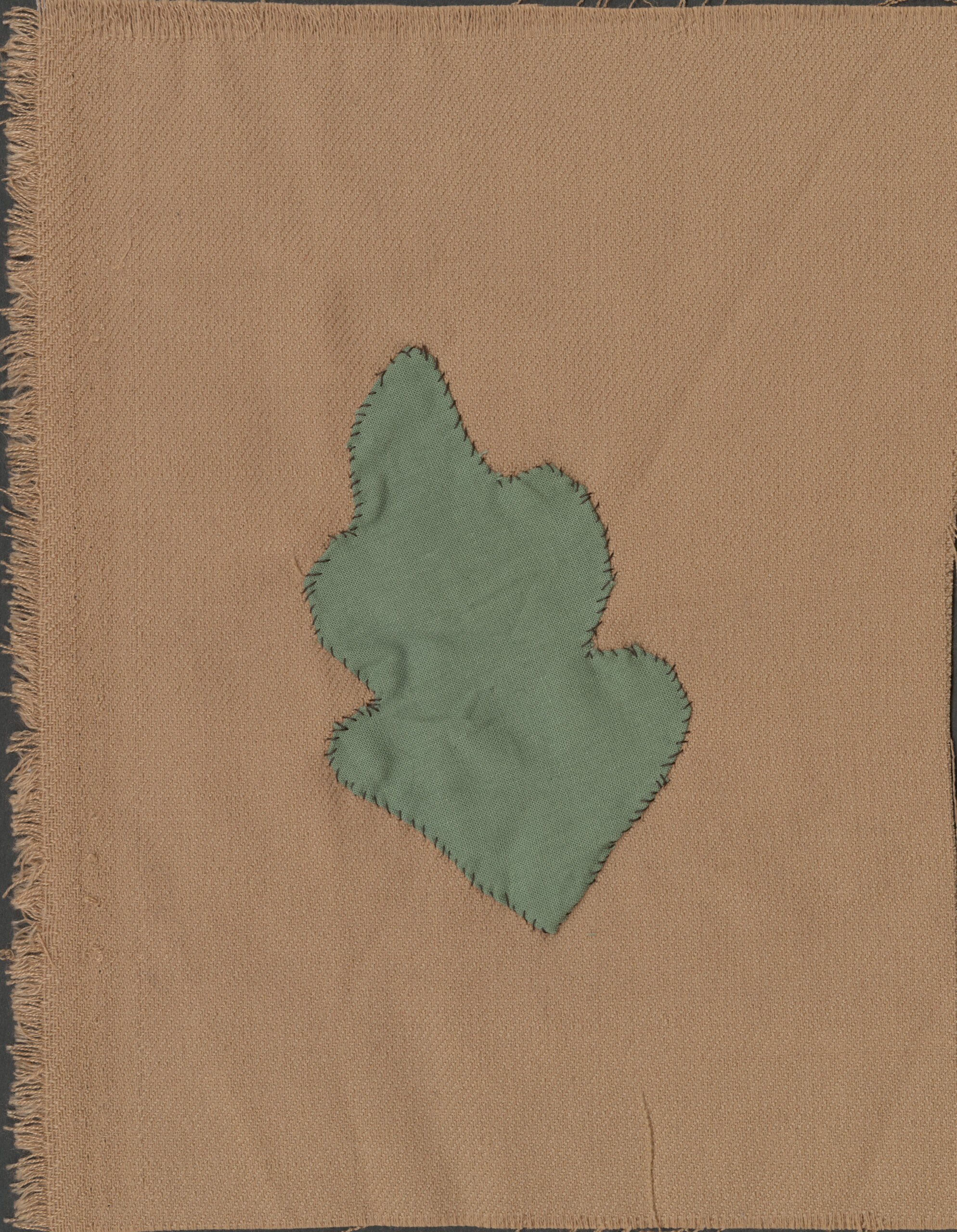

This quilt is part of the Weld-Grimké collection, presented by students from Eagleswood Academy, a boarding school founded by Sarah Grimké Weld and Theodore Weld. University of Michigan students recently studied this quilt in a classroom session held at the Clements Library, and reflected on the generations of labor, care, and hidden stories it represents.

Several of those boxes still sit in the Manuscripts Division office, right across from my desk. I look at them often, and think about Sarah Moore Grimké’s dream of a female Chief Justice eliciting laughter. I think about how some 90 years later when curators at the Clements were describing the collection that contained Sarah’s story, she was again diminished, this time to a “Grimké sister” and to one short, shared paragraph in a collection description. It’s a sharp and humbling reminder to me that all of us are products of our time. It is no surprise that in 1942 the status quo would be to describe a collection around the dominant male figure, just as it is no surprise that with the rise of feminism and the field of Women and Gender Studies in the 1960s and 1970s, Sarah and Angelina began to receive more recognition. By 2012 when Angelina and Sarah’s descendants generously donated another cache of family papers to the Clements, it was clearer to us at the library that the powerful women in the Weld and Grimké families deserved careful and explicit attention. The richness of the collection means it can tell many stories, but in recent years I have noticed that what tends to get the most attention revolves around women: students look closely at Angelina Grimké’s wedding purse, emblazoned with abolitionist imagery; we share scans written by free black and formerly enslaved women where they speak of their own experiences; scholars puzzle over the family Bibles annotated in Sarah and Angelina’s hands. Much has changed since the collection arrived in 1939— not only in how researchers interpret the sources, but also in how the library spotlights and describes them.

As much as we try, curators are not objective. Despite our best efforts, today we are surely missing things, too, and getting something wrong. The Weld-Grimké Family Papers finding aid was updated in 2016 to reflect current understandings of gender, historical agency, and archival best practices, but when I look at it again I can see places that merit revision. It reminds me of a letter I stumbled across in the James G. Birney Papers that was repaired at some point with a piece of cellophane tape, something that always makes library staff crinkle our foreheads. A penciled note appears beside it on the page: “Given the options, tape seemed the best solution regardless of what any persnickety archivist might think. – Ed.” What seems like the “best solution,” or the option that makes sense right now, might prove questionable in the future as our thinking and the historical context evolve. Progress is always incremental and never complete.

On this, our 100th anniversary, the call is for accountability. That we can look back and see where we mis-stepped, that we hold those lessons at the forefront of our thinking, and notice our own blindspots so we can do better for the generations to come. While we still await a woman to sit in that Chief Justice chair, I hope Sarah Moore Grimké would agree that the signs of the times are more promising than portentous and that the Clements is dedicated to accurately and justly describing our holdings. Even if we have to go back and revise as we grow and learn.

—Jayne Ptolemy

Assistant Curator of Manuscripts

The Threads That Bind Us

Oh reader, does it tangle.

If you have not held that delightfully simple tool in your hands, you may be surprised at the readiness with which your awareness will open to accommodate it. Sewing is a manylayered practice, regardless of the purpose—whether for form or for function, attached is a deeply sensory and emotional element. If you were to ask me, I would tell you that to sew is a tradition that spans centuries, eons, countries, continents—and the collections of the Clements too.

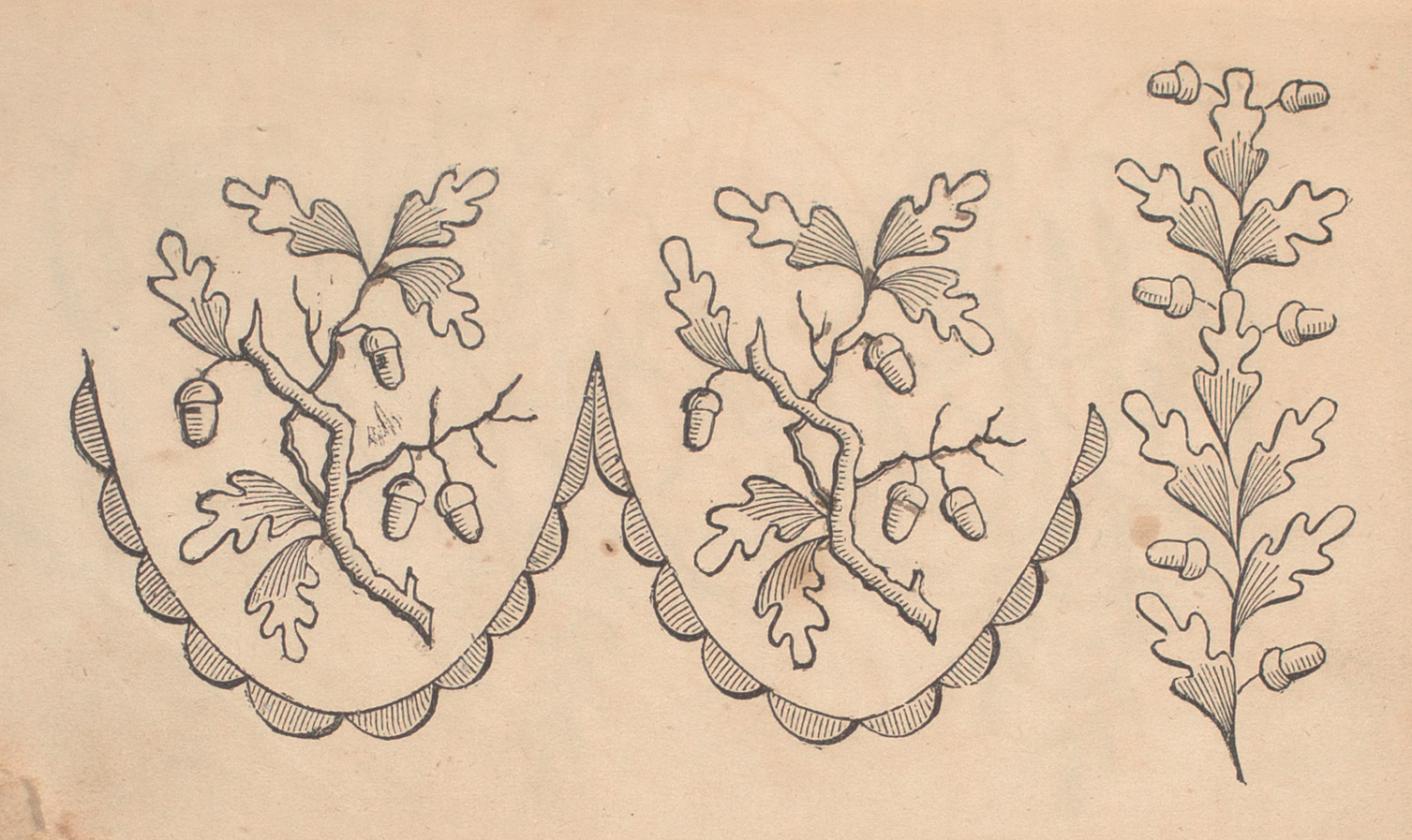

By now, it should come as no surprise to you that this humble writer is very fond of sewing. Although I will confess to not being the best at understanding directions for a number of things (including needlework), I have recently found delight in patterns for applique designs; even flat on the page, the shapes alone are pleasing to the eye.

So when I came upon a small book titled The Ladies’ Guide in Needlework (Philadelphia, 1850) on the second-floor stacks of the Clements Library, my first instinct was to take the most careful and delicate of peeks into this unassuming volume to see whether it contained any guides or illustrations for applique— and was happily surprised to find exactly what I was looking for.

I decided to try my hand at drawing those shapes out and stitch-stitchstitching them onto my fabric—a lovely, if not plain, beige color perfect for lush green leaves and nutty-brown acorns— and happily shared my intent with the colleagues at the Clements with whom I have found community and camaraderie, built largely around the craft.

It’s a blessing increasingly recognized by scholars and researchers, too, as the “material turn” over the past several decades in the fields of History and American Studies attends to how physical artifacts can tell us much about the past. How something was made, what it was made of, who was acting in community while it was made, are important questions in their own right. That importance is now recognized and renowned, as we see by Tiya Miles’ recent book All that She Carried (New York, 2021), which centers the sewn object as a way to build out a complicated, embodied history of love and loss, winning the National Book Award and gracing the New York Times bestseller list. So, too, has teaching picked up on the power of the physical object and its creation to help students learn. The growth of “experiential learning,” or hands-on workshops, echo the lessons seen in Material Culture Studies, and in my own experience: we can learn by doing, about the subject at hand as well as ourselves.

— Meg Bossio

Reference Assistant

Illuminating Revolutionary War America

The papers of British General Thomas Gage have been the most queried, requested, researched, and otherwise utilized materials at the William L. Clements Library—from their arrival at the Library in 1937 to the present day. A National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant to digitize the Gage papers coincides with the Centennial of the William L. Clements Library. In keeping with a central tenet of the Clements Library’s mission statement, to “support and encourage scholarly investigation of our nation’s past . . . and make . . . materials available to students and the broader public,” the digitization of the Thomas Gage Papers will facilitate remote access to this internationally significant collection through freely available online publication.

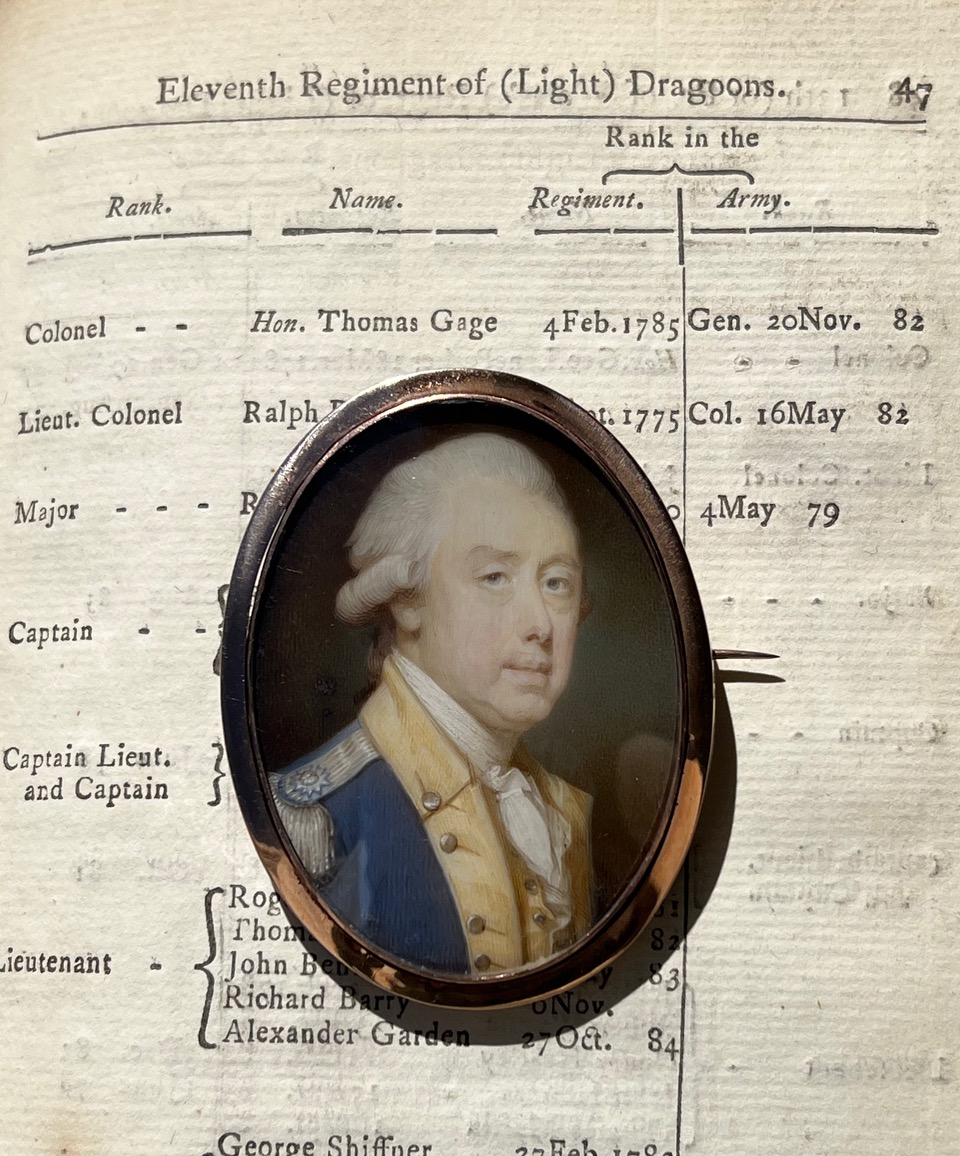

The Clements Library is pleased to reveal this hitherto unrecorded 2¼” oval miniature portrait of Thomas Gage. He wears the uniform of the 11th Light Dragoons, the regimental coat indicating his colonelcy (held between 1785 and his death in 1787). Almost certainly Gage’s last portrait, his wife Margaret Gage may have worn it at least in the early period after her husband’s death. Painted by artist Jeremiah Meyer (1735–1789) on ivory, rose gold rim, pin back, necklace chain holes, cobalt blue backing, ca. 1785–1787. Discovered by Christopher Bryant and acquired by the Clements Library, 2022, thanks to the generosity of Benjamin and Bonnie Upton, and Margaret Trumbull.

Thomas Gage was a career military officer, who served in America during the Seven Years’ War, as military governor of Montreal (1760–1763), as commander in chief of the British Army in North America (1763–1775), and as governor of Massachusetts Bay (1774– 1775). General Gage’s extensive papers are comprised of over 23,000 letters, documents, intelligence reports, muster rolls, depositions, treaties and proclamations, engineering assessments, financial papers, maps, and broadsides, largely dating from his service in America between 1763 and 1775. As the head of the military in North America, Thomas Gage was also the senior government official in the American colonies. Consequently, his papers are rich with information about the British attempt to gain control over areas taken from the French in the Treaty of Paris (1763), relations with the indigenous populations, and the tumultuous years leading up to the American War of Independence.

Access to the Thomas Gage Papers has increased over the years, with improved tools for navigating the sea of manuscripts. From 1937 to the early 2000s, researchers consulted printed guides, bibliographic entries, a card catalog, name lists, and rudimentary catalog descriptions. In 2010, the National Endowment for the Humanities provided the Clements Library with funds to create a robust online finding aid and supplementary subject indices to make this voluminous collection accessible to scholars with interests in a range of content. The current digitization project spanning 2021–2024—also funded by the NEH—will result in the online availability of scans of every manuscript, permitting users to connect with the collection whether or not they have the resources to travel to Ann Arbor. The inclusion of metadata and notes will give users a new way to engage with subject matter and personalities. While not part of the NEH digitization grant, the Clements Library is reviewing options for securing transcriptions of the complete Gage collection.

The Thomas Gage Papers are a treasure trove of primary sources on pivotal events leading up to the American Revolution: the Stamp Act of 1765, the Boston Massacre of 1770, and the Battle of Lexington and Concord in 1775, to name a few. Several Stamp Act-related manuscripts include a letter that Thomas Gage wrote to Secretary of State Henry Seymour Conway on September 23, 1765. In it, Gage provided a detailed account of the uproar which greeted the Act in the colonies. He began “Tho’ you will have received accounts from the Governors of the several Provinces, of the Clamor, Tumults, and Riots that the Stamped Act has occasioned in the Colonies; Yet as the Clamor has been so General, it may be expected Sir, that I should likewise transmit you some account of what has passed.” Gage informed Conway of the Virginia Resolves passed by the Assembly of Virginia, which claimed that in accordance with British law, Virginians could only be taxed by an assembly of representative officials they personally elected. Thus, they deemed the Stamp Act to be unlawful. As such, the Assembly of Virginia, “gave the signal for a general outcry over the continent . . . they have been applauded as the protectors and assertors of American liberty.”

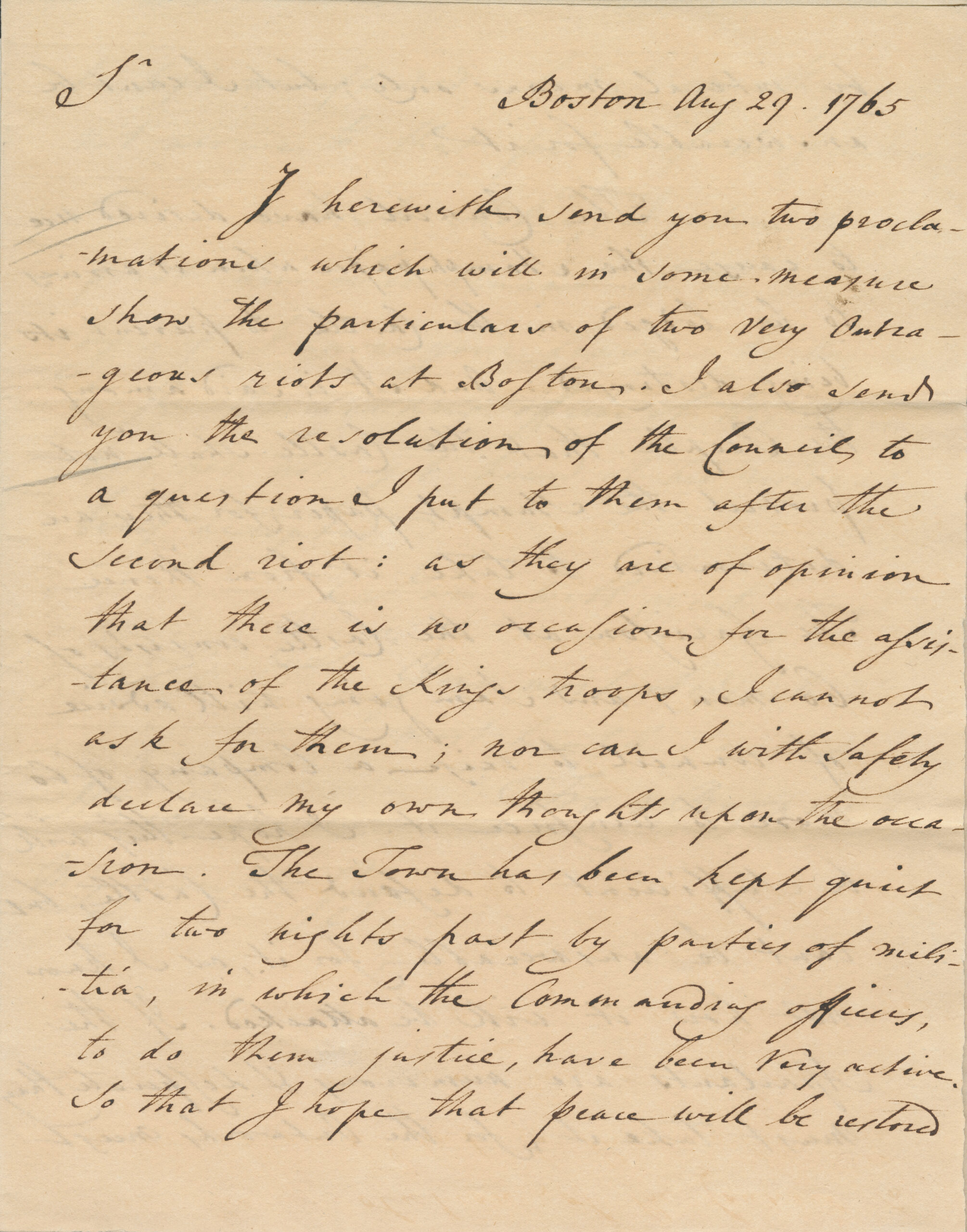

Around 50 letters and documents in the Thomas Gage Papers pertain to riotous behavior and other responses to the Stamp Act. Reports came to Gage from as far north as Nova Scotia and as far south as Florida. This example is a letter from Massachusetts Governor Francis Bernard reporting on riots in Boston and the impending arrival of stamped paper: “The Council have desired me to cause the Stampt paper when it arrives to be lodged in the Castle to prevent its being destroyed : And It is said among the People that the Castle shall not protect the Stampt paper for they are determined to take it from thence” (August 29, 1765)

Gage continued by detailing the successful efforts of rioters across the colonies to pressure Stamp Officers to resign their posts “by menace or by force,” destroy stamped papers, and coerce assemblies into repealing the Stamp Act. In Boston, the populace “took the lead in the Riots and by an assault upon the house of the Stamp Officer, forced him to a Resignation.” Meanwhile, “[t]he little turbulent Colony of Rhode Island raised their Mob likewise” and not only forced a Stamp Act official to resign, but destroyed the homes of prominent loyalists. Gage then noted that the neighboring provinces would have likely seen similar scenes, had there not been an “almost general resignation of the Stamp Officers.” The southern colonies were broadly peaceful, though Maryland saw the house of a stamp officer “pulled down and his effigies burnt.” Eventually, Gage wrote, the people “began to be terrified at the spirit they had raised, to perceive that popular fury was not to be guided and each individual feared that he might be the next victim.” Gage concluded his report by informing Conway that “[e] verything is quiet at present and a calm seems to have succeeded the storm.” Gage noted, however, that as the Stamp Act wasn’t set to take effect until the first of November, “the final issue of this affair will be soon determined.” As the NEH digitization grant progresses, researchers and the general public will have ready access to this letter in its totality and within the context of its creation.

Another flashpoint in British-colonial America was the passage of the Townshend Acts in 1767 and 1768, designed to tax the colonies on imports from Great Britain, such as glass, paper, and tea. On March 5, 1770, Bostonians took to the streets in protest, resulting in the event remembered as the Boston Massacre. Reporting on the protest, Gage informed Secretary at War William Barrington, “Your Lordship will have heard Accounts of the unhappy Quarrell between the People of Boston and the Troops quartered there; in which five of the former were killed” Enclosed with this April 24, 1770, communication is a vivid description of the Boston Massacre titled “A Narrative of what happened at Boston, on the Night of the 5th: March 1770.” A sample of the document includes:

[O]n the Night of the 5th: of March . . .

They began by falling upon a few

Soldiers in a Lane, contiguous to

a Barrack of the 29th: Regiment.

The Mob followed, Menacing and

brandishing their Clubs over the

Officers Heads to the Barrack Door . . .

Part of the Mob broke into a

Meeting House and rang the Fire

Bell, which appears to have been

the Alarm concerted for Numerous

Bodys immediately Assembled

in the Streets, Armed some with

Musquets, but most with Clubs,

Bludgeons, and such like Weapons

. . . . Officers . . . were repairing to

their Posts, but Meeting with Mobs

were reviled, attacked, and those who

could not escape, knocked down and

treated with great Inhumanity. One

of the Soldiers recieving a violent

Blow. . . . Captain [Thomas] Preston

turned round to see who fired, and

recieved a Blow upon his Arm,

which was Aimed at his Head.

When the mob of Bostonians did not see any “Execution done,” the crowd “grew more bold, and attacked with greater Violence, continually Striking at the Soldiers and Pelting them . . .”.

Formal narratives like this/these provide details of the violence and ensuing consequences that can only be appreciated through direct reading. These original manuscript sources as they physically appear (via digital surrogate) bring us closer to these familiar people and events in a palpable way.

The breadth of subject matter, geography, data, and perspectives in the Gage papers offers a path to diverse scholarship. Insights into the lives of marginalized individuals and groups may be found throughout these manuscripts. Direct engagement with the sources reveals military, legal, and social aspects of slavery and Africandescended peoples, women and gender-related topics, and more.

One window into these underrepresented lives is a series of letters involving Captain Lieutenant Charles Osborne, the commanding officer of Ticonderoga, and his subordinate, James Cahoon. By letter, Osborne informed Gage that Cahoon’s wife, May (or Mary) Cahoon, applied to him for protection because her husband had been abusing her in ways “not possible to describe.” As a result, Osborne separated James Cahoon from his wife and sent him to his barrack room. Yet Gage also received letters from Lieutenant Colonel John Beckwith at Crown Point relating an alternate version of the story. Beckwith wrote that James Cahoon informed him that Cahoon had “caut his Captain [Charles Osborne] in bed with his wife” and that when Cahoon complained, Osborne imprisoned him for ten days. Beckwith reminded Osborne that May Cahoon’s husband “has a right not only to demand his Wife, but to take her where ever he can find her to live with him if he chooses it and no one has a right to keep her from him without his consent or approbation.” Beckwith proposed that Osborne address the situation by sending May Cahoon away from the military post and to her family, which Osborne refused to do. The men appealed to Gage, the commanding general, for a final decision, and the resulting opinion was that Osborne “commands independently” and that Beckwith should stay out of the situation.

The Cahoon story brings into stark relief the subjugation of women and evidences the ways in which masculinity was weaponized to maintain the male-dominated military hierarchy. Very little has been published citing these letters, and less that is freely available to the public. This episode takes up little space in the grand sweep of military and political events that pervade the Gage Papers, but it was life-changing for May Cahoon. Not hearing her voice amid the arguments and judgments of the men involved, we can only speculate on her thoughts, preferences, and feelings.

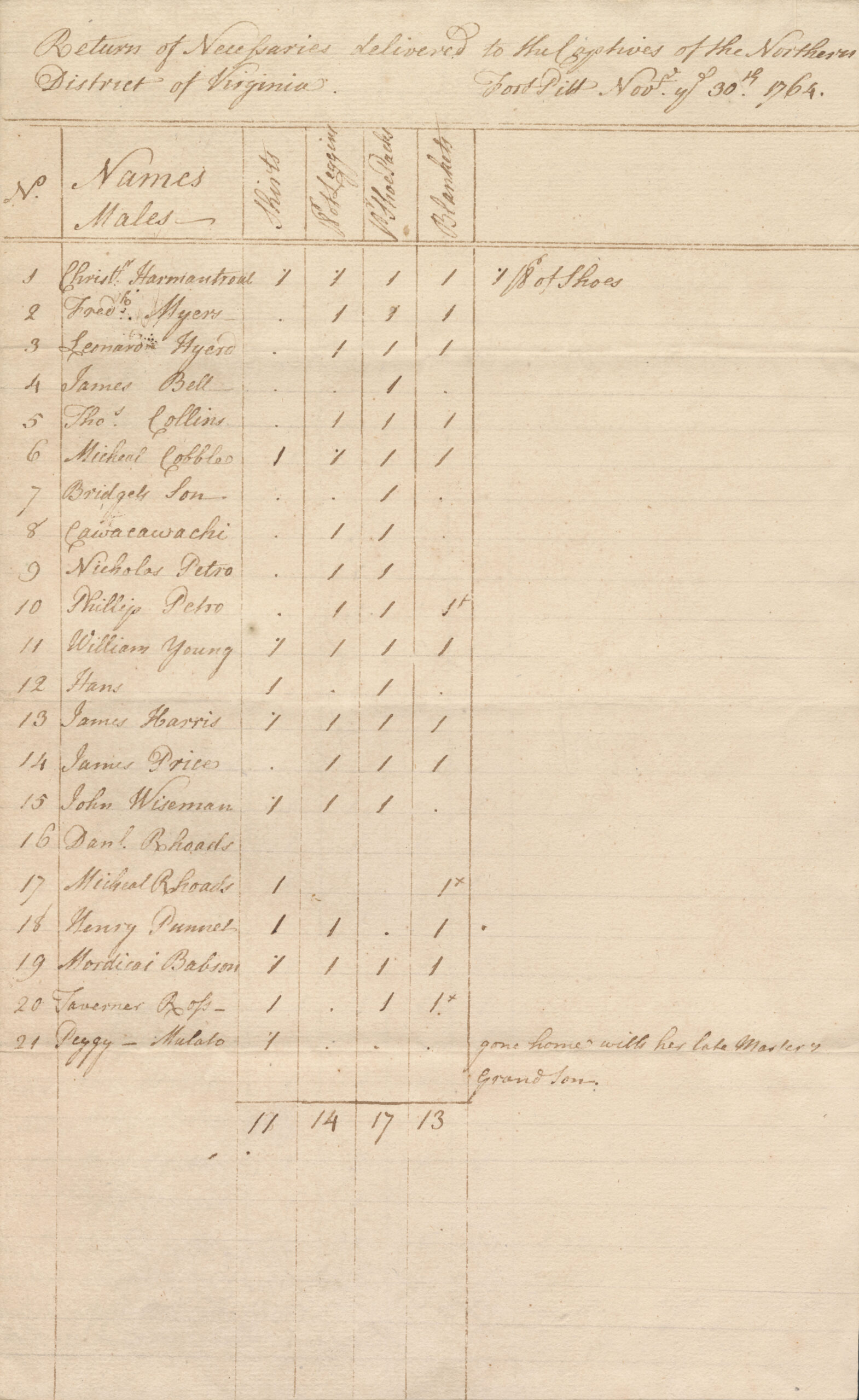

Military return documents provide accounting for personnel, property, or supplies. These routine manuscripts often include everyday people not otherwise remembered in the historical record. Following Pontiac’s war against the British, Henry Bouquet treated with Shawnee and Delaware Native American peoples in October 1764. This return documents clothing supplied to captives of Native American tribes who were released “back” into the colonial population. These captives often had integrated into tribal communities and had families there. Peggy, a woman of mixed racial or ethnic descent, was removed back into the hands of the grandson of her late enslaver. Many men, women, and children are all but untraceable without documentation such as this. The digitization of the Thomas Gage Papers will provide a wider opportunity to uncover their stories.

Even with thorough indexing and description, the series of letters on the Cahoons is challenging to locate, especially for novice researchers. Careful consultation with the library’s online volume descriptions includes a single sentence: “Captain Osbourne is accused of detaining and ‘cohabitating with’ James Cahoon’s wife at Fort Ticonderoga.” And even in the library’s own description, May Cahoon lacks a name, agency, and autonomy. A close review of the library’s subject index will identify these letters under entries for “Women,” “Women, adultery,” “Women, violence toward”, and “Infidelity,” all of which are accurate, but learning the entire story requires the time and resources to consult the original materials. The NEH-funded project to digitize the Thomas Gage papers is a game-changing opportunity for researchers to uncover primary sources for experiences like those of May Cahoon, without the pressure of a library closing bell or lack of travel resources. Younger scholars who struggle with cursive handwriting will be able to study the papers without the limited time afforded by the reading room.

The availability of these materials will transform scholarship on the late 18th-century Anglo-American world. Such scholarship would help better understand the United States in global histories of empire. Scholars working in Indigenous Studies will continue to enrich histories of Native American resistance to settler colonialism. The Gage papers have supported decades of publications and dissertations on military and political history, revolutionary people and events, merchants and financial agents, and grand intellectual and ideological discourses that have shaped how we understand American history. New historiographic approaches, analytic tools, and changing subject focuses have and will continue to march on. Alongside its stunning documentation of prominent people and events, we look forward to expanding insights into the everyday—historically underrepresented persons; persons without access to resources or sociopolitical or financial power; family; interpersonal relationships on small scales; sexuality; the environment; and practical challenges of simply being alive in colonial America. Whether for macroor micro-history, the Thomas Gage Papers continue to be read afresh.

— Tulin Babbitt, Katrina Shafer, and Michelle Varteresian

NEH Project Digitization Technicians

Elegant to Eccentric

And what treasures to choose from! The Clements collection is a book collector’s (and binding historian’s) dream—William L. Clements eventually gathered an immense variety of binding styles, including many “extra” and fine bindings made by the most famous binders of his time and before, some original to the imprint, some as rebindings, including a Jean Grolier-style strapwork binding of great beauty, bindings done in Harleian and Etruscan style, and signed bindings by John Roulstone (1770 or 1771–1839), Christian Kalthoeber (active 1780–1817), W. T. Morrell, Robert Riviere (1808–1882), Sangorski and Sutcliffe, and Francis Bedford (1799–1883), among others.

Thinking about the exhibit as I write this reminds me of how things have changed with regard to historical bindings. Usually only the rarest, most expensive, and most beautiful bindings were ever seen; more pedestrian items, unless they contained a very important text or important illustrations, tended not to appear in binding exhibits. Today things are very different: there is abundant interest in the entire history of the book, and this includes not just content, but every aspect of a historical exemplar—the materiality of the book has come into its own. All aspects of the physical book, from paper type, writing and printing qualities, sewing and support structures, cover materials and decoration— all of these elements are examined, identified, described, protected—and shown. This revaluing of even ordinary historical bindings, once ignored, adds value to them in both monetary and intellectual ways—and influences the decisions collection managers make about them. Following are some favorites.

— Julia Miller

Author, Books Will Speak Plain: A Handbook for Identifying and Describing Historical Bindings, and Meeting by Accident: Selected Historical Bindings.

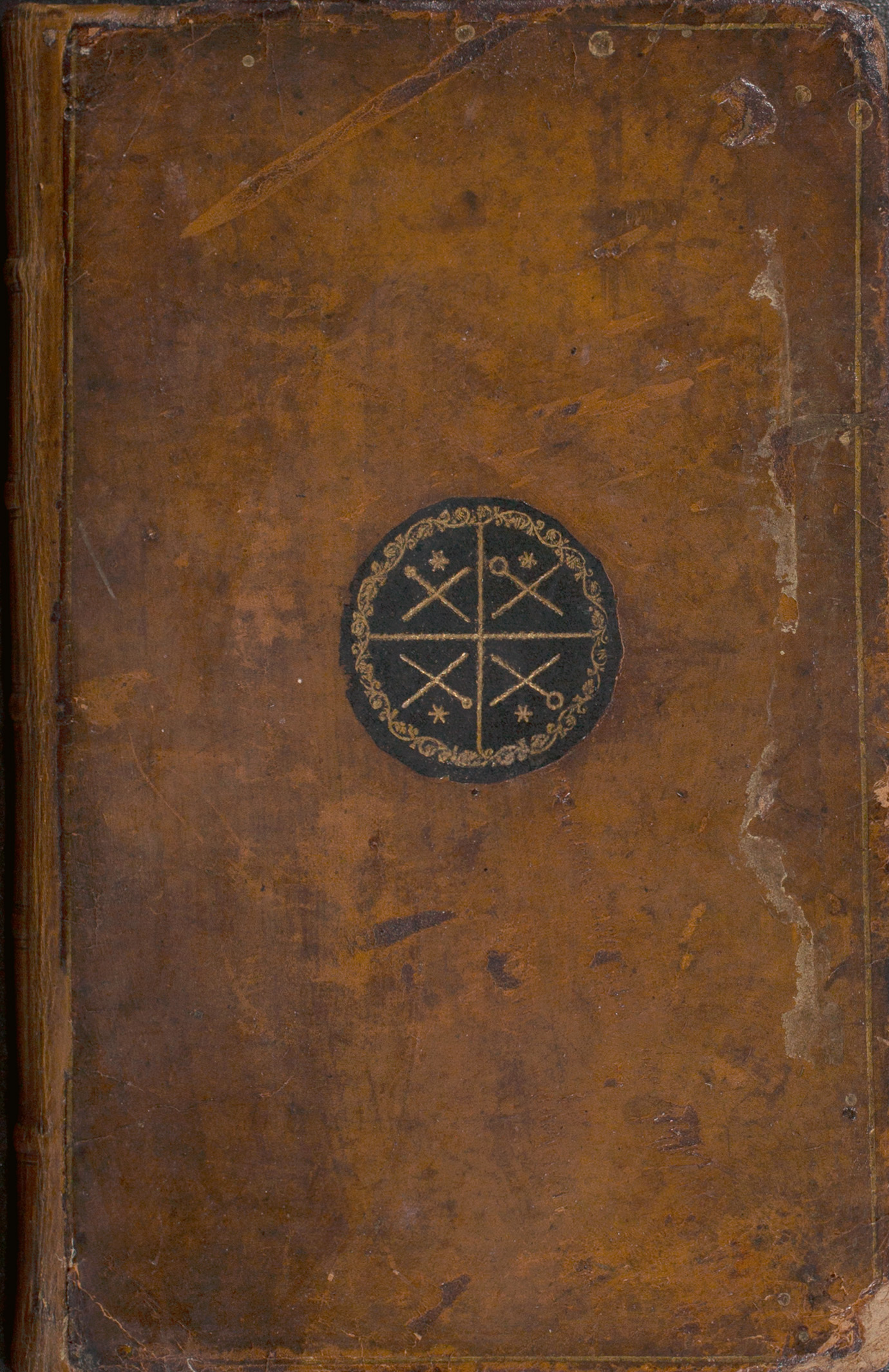

A Proposal to Determine our Longitude, by Jane Squire (1671?-1743). 2nd ed. London: Printed for the Author . . . , 1743.

Squire participated in (but was ignored) during the competition to find an accurate way to calculate longitude at sea. She may have failed, but her choice to decorate her book broke a convention long held by binding historians: book decoration did not reflect content before 1800. The black roundel on Squire’s cover, tooled with her invented symbols, did exactly that.

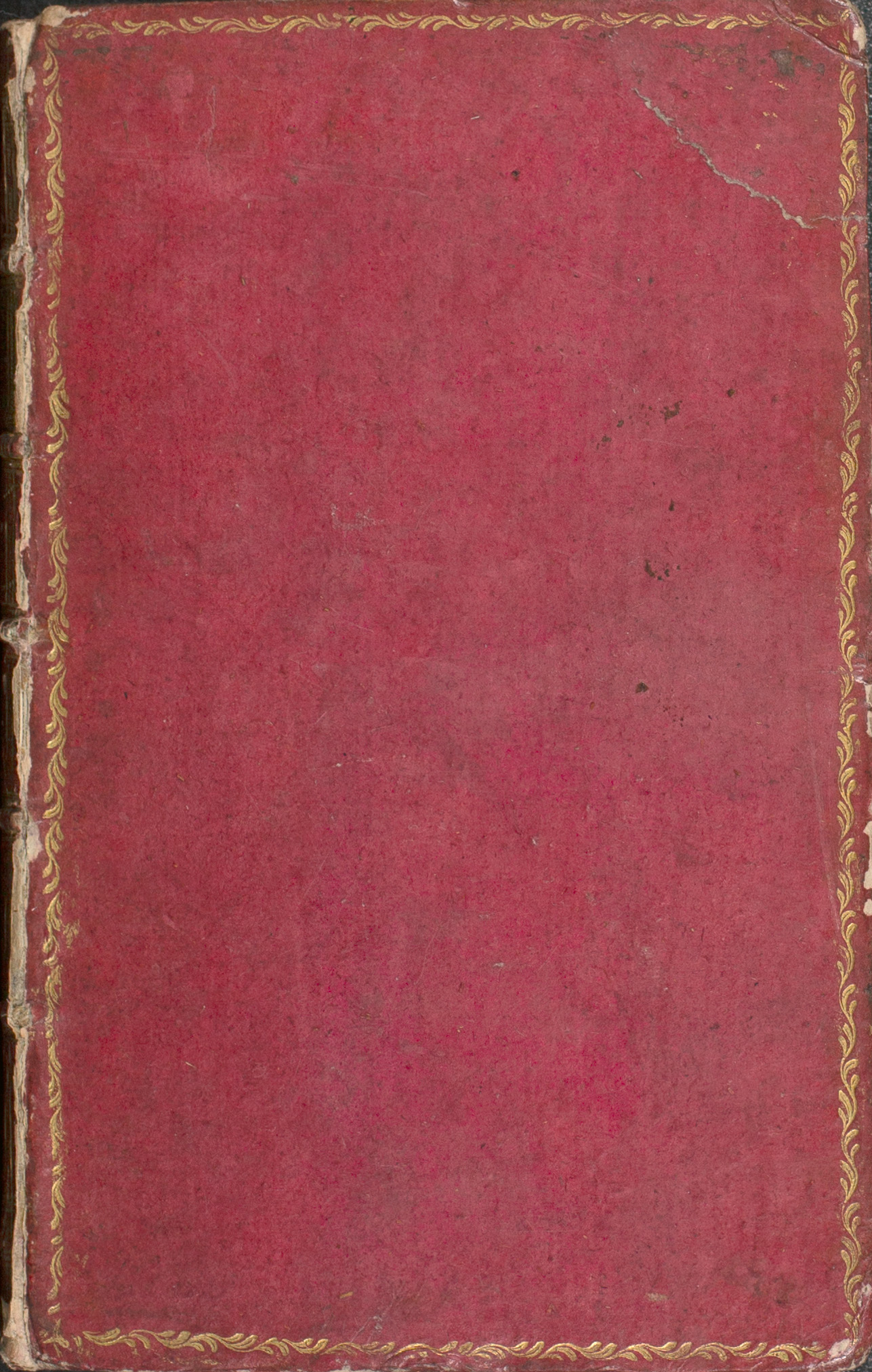

A Declaration of the People’s Natural Right to a Share in the Legislature . . . , by Granville Sharp (1735-1813). London: Printed for B. White, 1774.

A dark pink surface-colored paper binding, tooled in gold. Sharp was well known for his liberalism and anti-slavery beliefs—and his practice of having his arguments printed and bound up in such attractive (and relatively inexpensive) paper bindings—which he gave away.

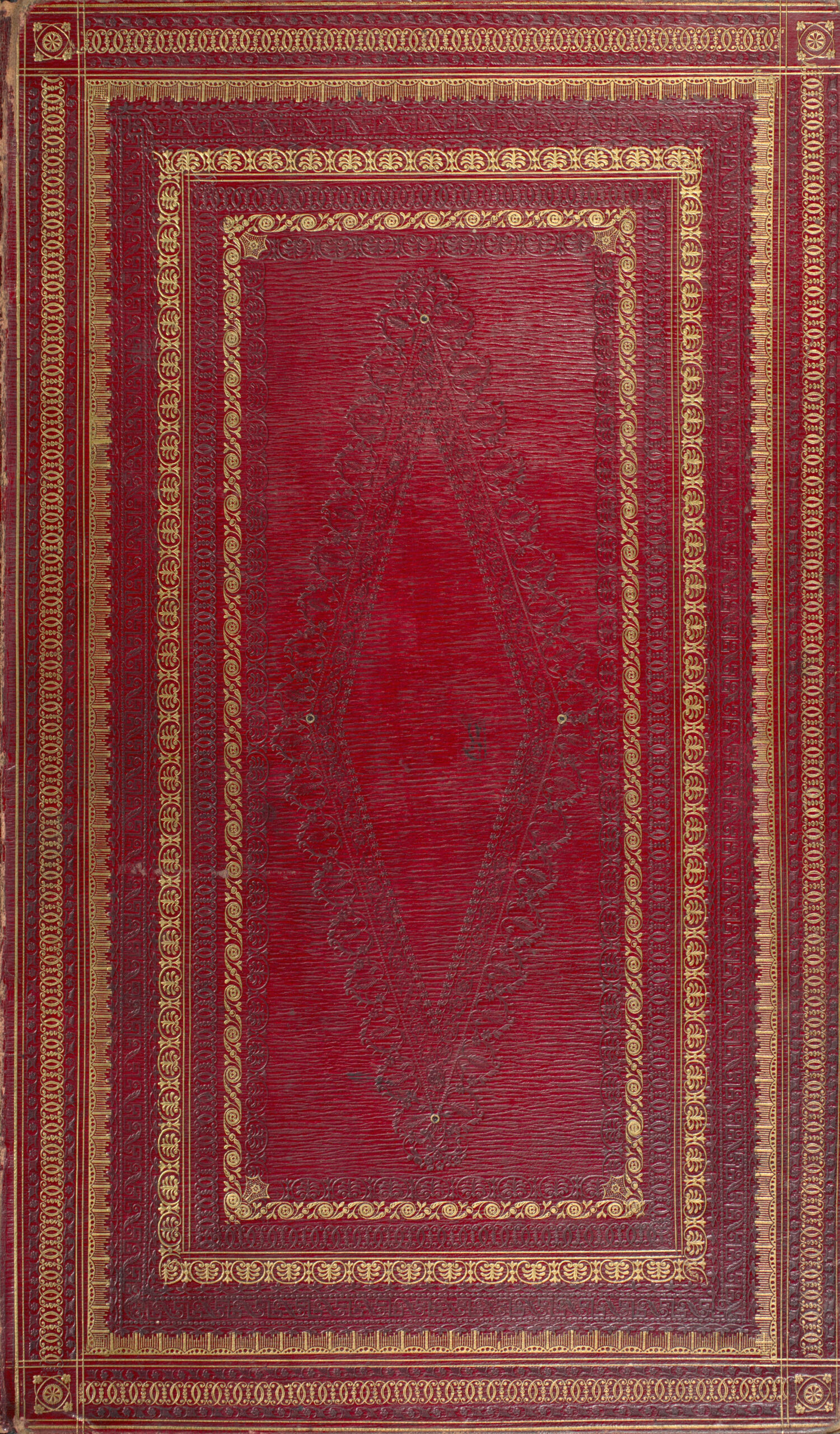

The Book of Common Prayer . . . . New-York: By Direction of the General Convention, Printed by Hugh Gaine, 1795.

John Roulstone bound two copies of the Common Prayer, in identical dark-red straight-grained goatskin and signed both in gold inside the lower cover edge. Roulstone’s skill can be seen at once in the craftsmanship and tooling of this magnificent binding; he is arguably the best American binder of his era.

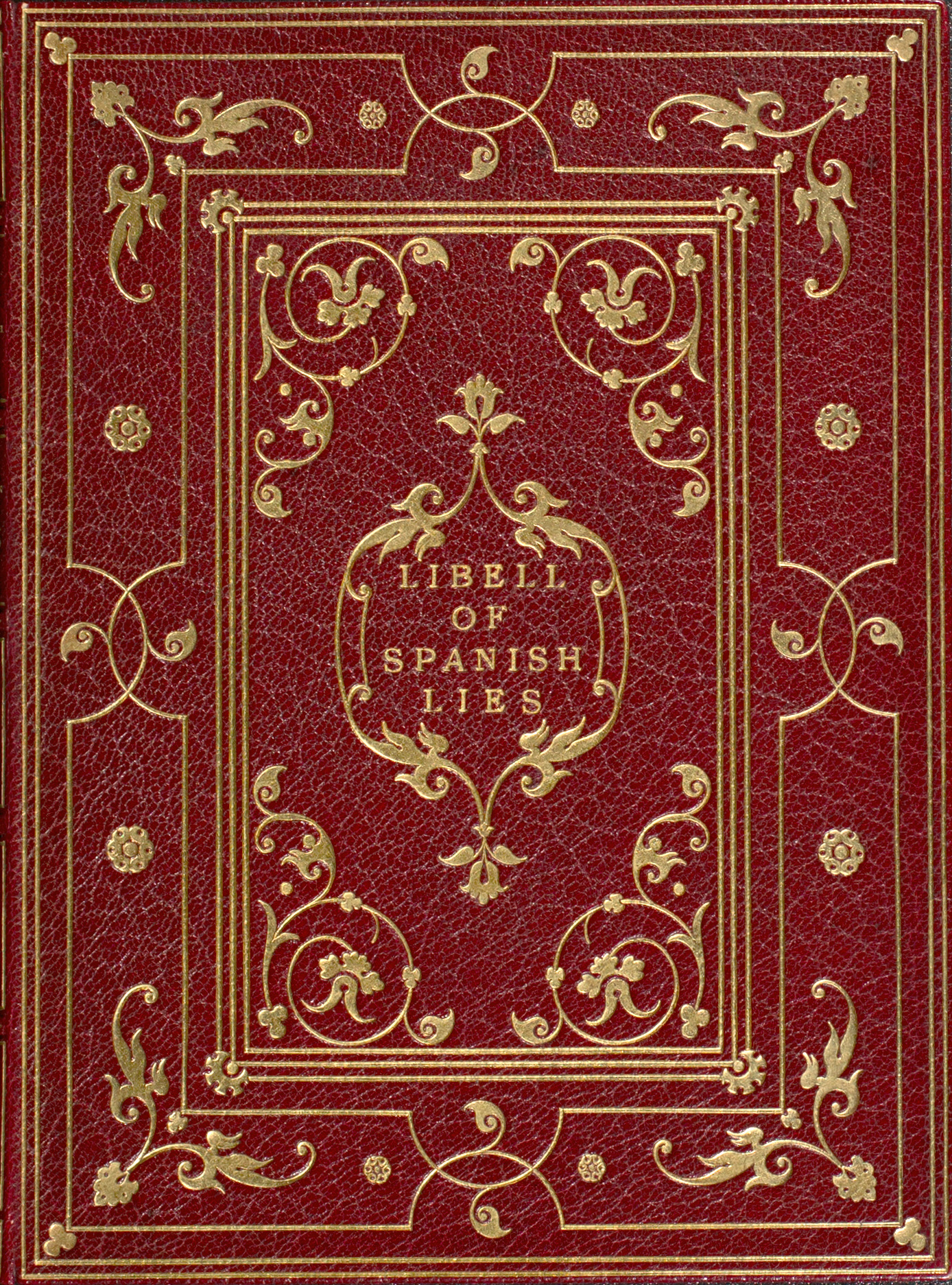

A Libell of Spanish Lies, by Capt. Henry Savile. London: Printed by John Windet, 1596.

Gold-tooled corner-and-centerpiece design, borrowing the famous Aldine Press centerpiece titling style; the Aldine style of titling became a vogue and is seen on some of Jean Grolier’s bindings. Bound by Rivière and Son, London.

An Theater of Mortality, or, The Illustrious Inscriptions Extant upon the Several Monuments . . . , by Robert Monteith, M.A. Edinburgh: Printed by the heirs . . . , 1704.

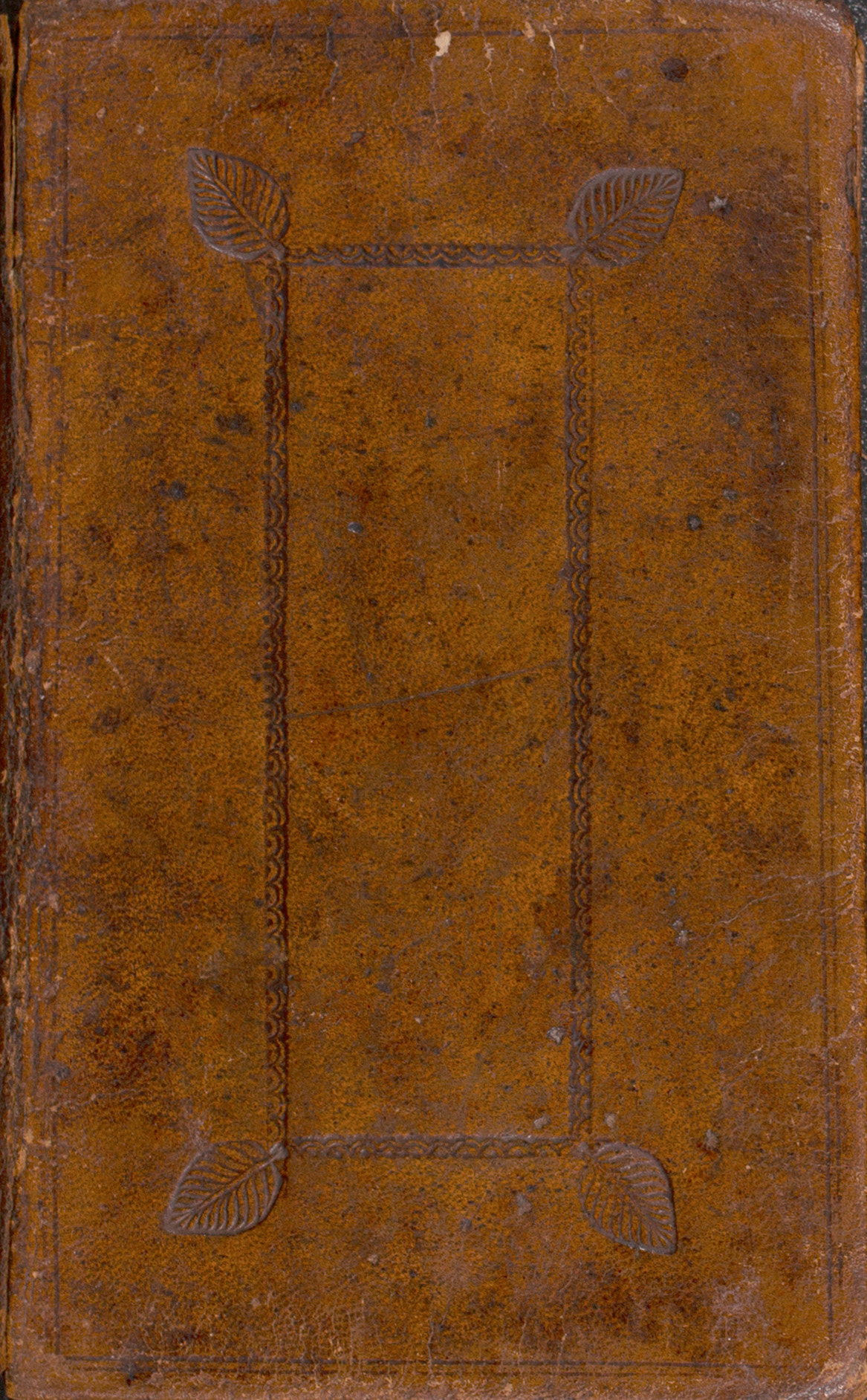

A blind-tooled panel binding of sheepskin: a dot-andscallop roll used around the center frame, with an exquisite leaf-shaped fleuron tooled at the corners. The decoration is simple, well-executed and attractive.

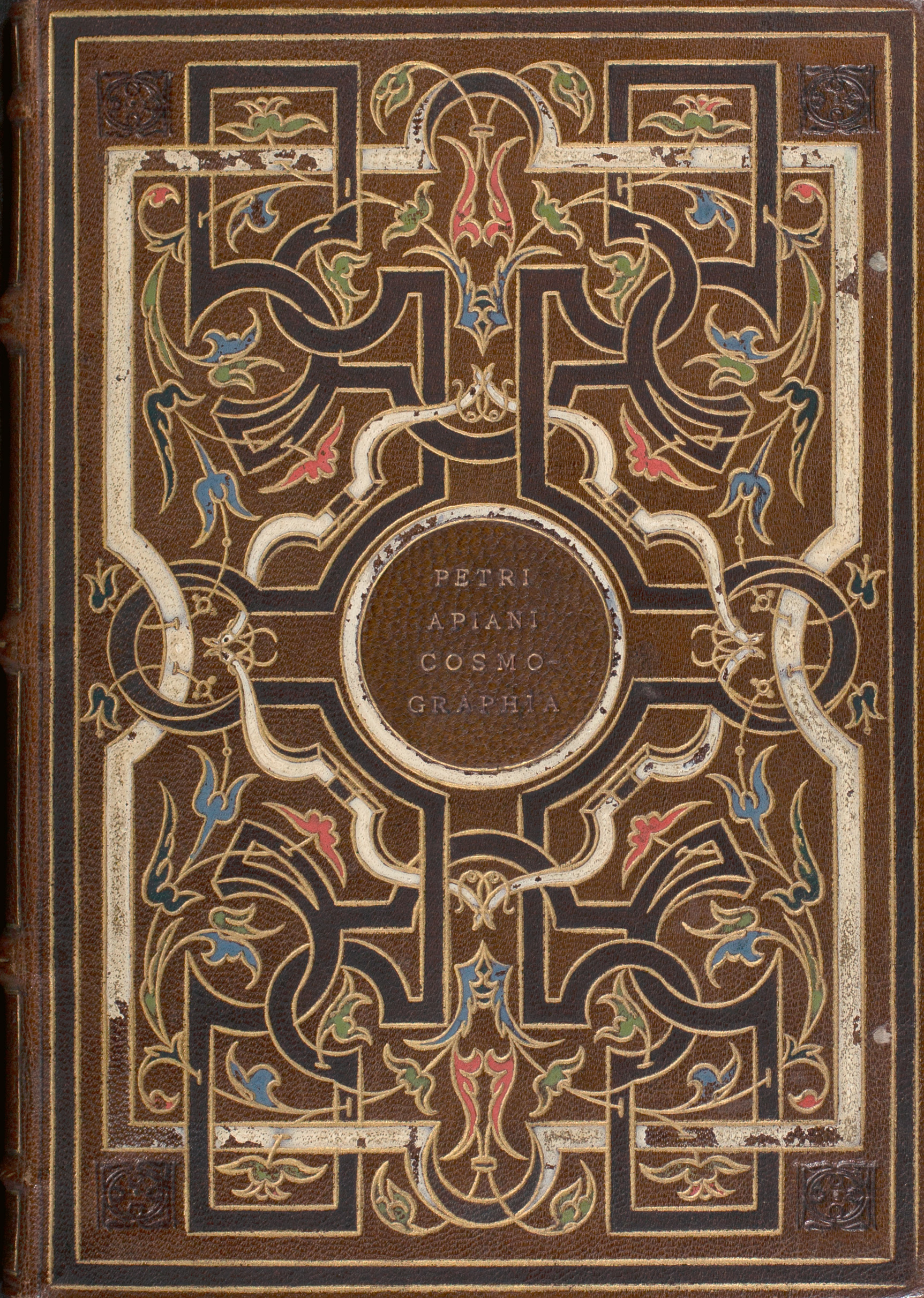

Cosmographia Petri Apiani, by Peter Apian (1495–1552). Antwerp: Gregorio Bontio, 1550.

Gold-tooled Grolier-style strapwork binding, the strapping painted white and black, with small touches of green, red, blue and black; gilt and gauffered edges are by Hagué.

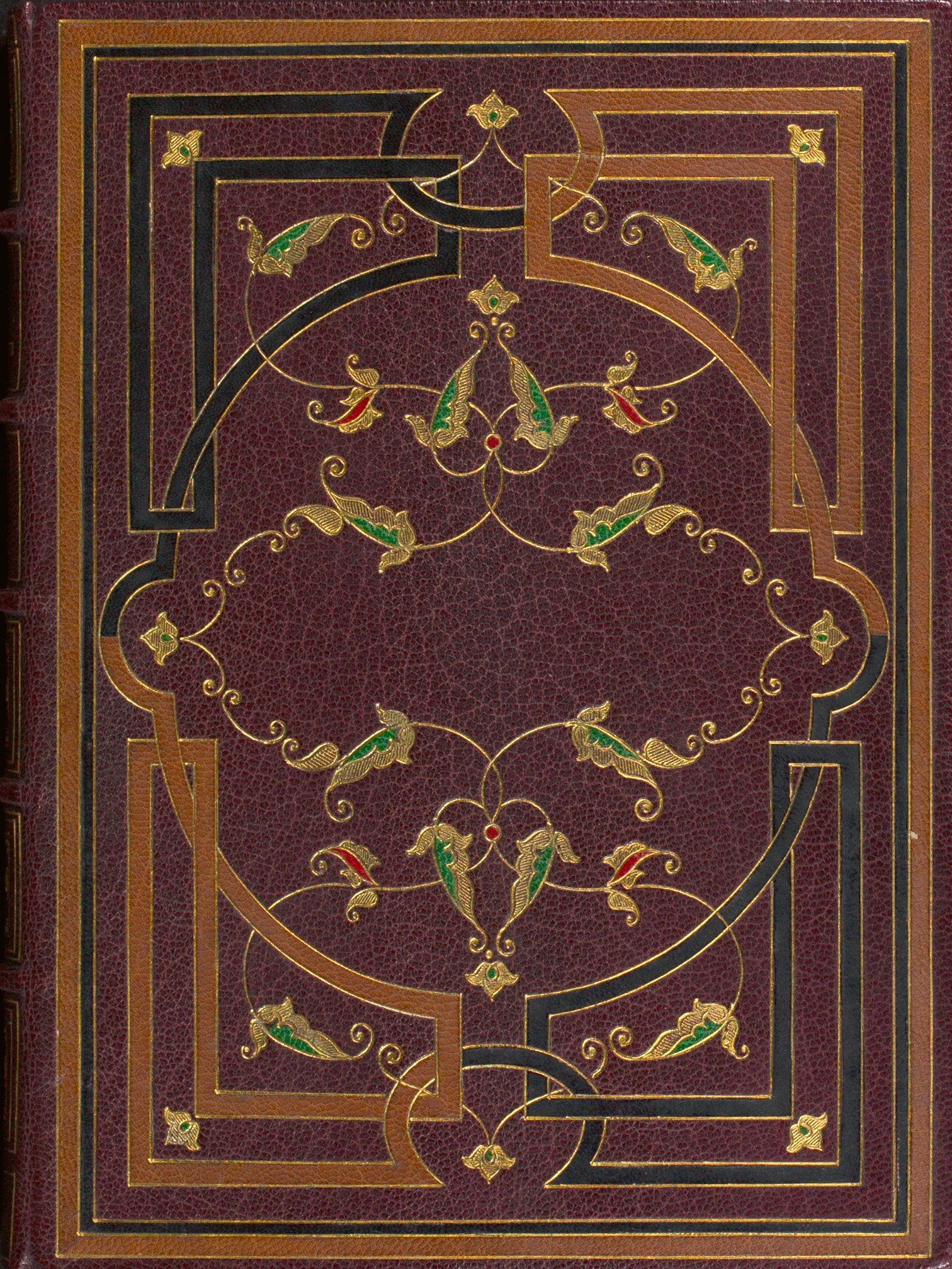

America Painted to the Life, by Sir Ferdinando Gorges (1565?–1647). London: Printed for Nath. Brook, 1658–1659.

Gold-tooled interlace strapwork design, employing azured tools and colored leather inlays. Bound by Sangorski and Sutcliffe, London.

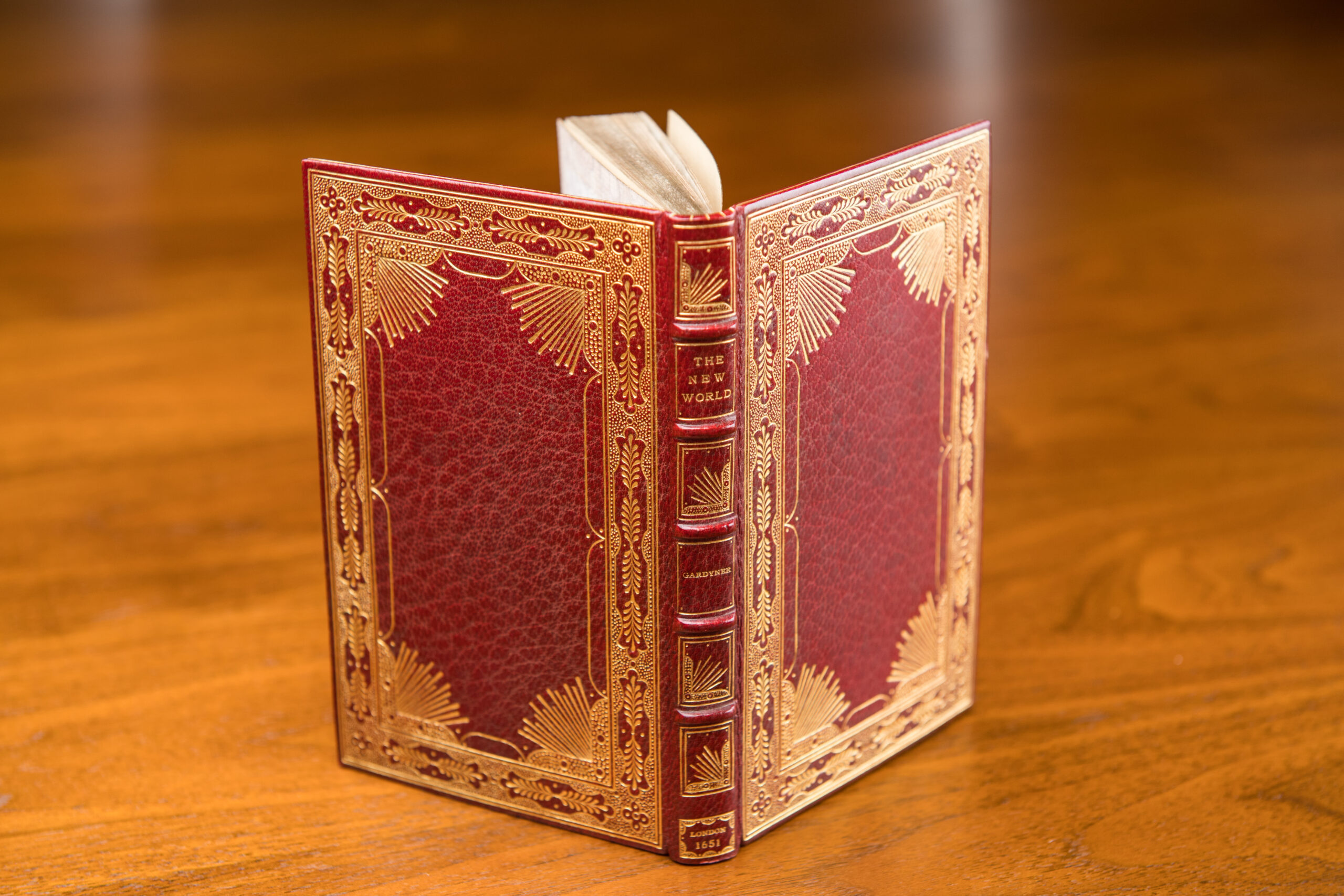

A Description of the New World, Or, America Islands and Continent, by George Gardyner. London : Printed for Robert Leybourn, 1651.

Exquisite gold-tooled cornerpiece style, combining quarter-fan corners and intricate panel borders filled with pointillé, by H. Zucker.

Mysteries of the Deep

We all love sea serpents, and we all love mysteries. And a recently acquired example of great lithography ticks both of those boxes.

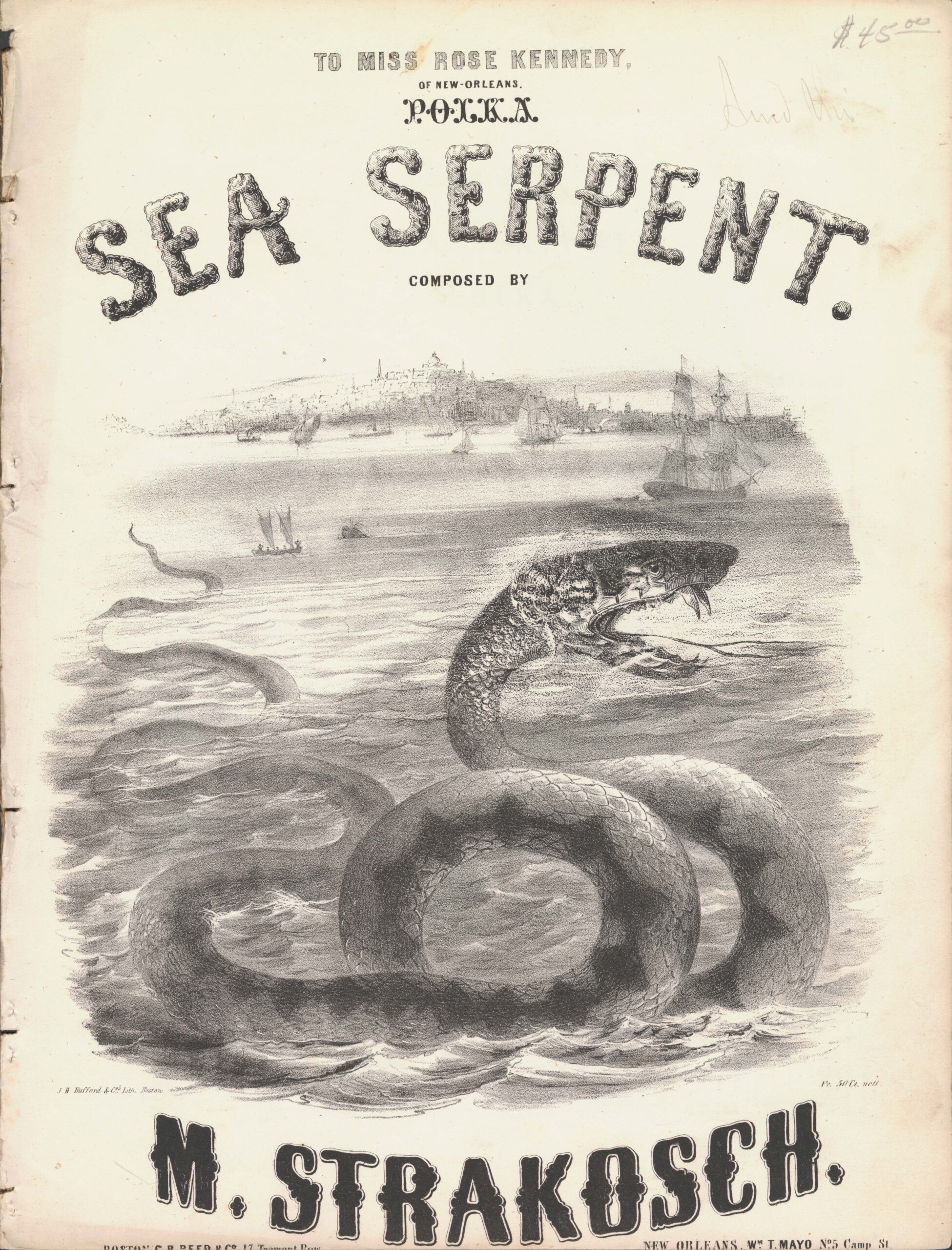

Sea Serpent Polka, composed by Moritz Strakosch (-1887). Louis Xavier Magny and Louis Audibert, lithographers. New Orleans, [1850s].

I was immediately attracted to this item because we have other prints and related stories of sea serpent sightings along the East Coast in the 19th century. This wonderful Sea Serpent Polka was printed in Boston by one of the great lithographers, John H. Bufford (1810– 1870), and was distributed by retailers in both Boston and New Orleans.

The lithographer has given us a nice view of Boston Harbor, with the State House as a backdrop at the top of the hill. But if you look at the head of the serpent, there’s a shadow of what could be another drawing, as if something had been altered in the production of the lithographic stone. And this is something you don’t often see, especially from one of the top lithographers in the business. There had possibly been another head on the sea serpent that had been erased and replaced with the present one. But the erasure hasn’t worked completely, and that intrigued me as an example of the printing process revealed by this sheet music cover.

The dedication at the top is to Miss Rose Kennedy of New Orleans, by Moritz Strakosch, a European composer who worked in America. After a little investigating, I learned that Rose Kennedy was the daughter of John Kennedy, superintendent of the United States Mint in New Orleans. Rose Kennedy’s debutante ball took place in the Mint, one of the great social galas of the year 1850. I have to guess that our composer Mr. Strakosch may have been there and been very impressed by Miss Kennedy, and hence this dedication.

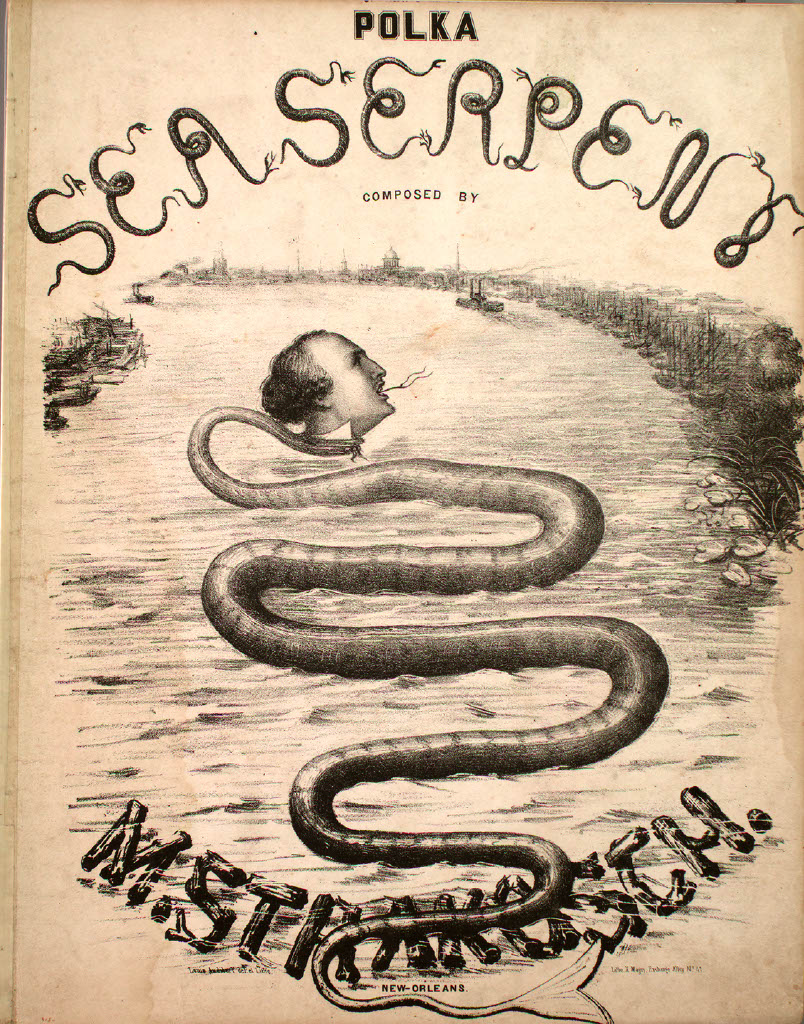

I also found another version of this song. This is unfortunately not from our collection, but from the great Lester Levy Sheet Music Collection at Johns Hopkins University. It has a lot in common with the version above, only this was printed in New Orleans. The view of Boston has been replaced with a view of the Crescent City along the Mississippi. You can also see that the typography is different. But what catches your eye is that the serpent now has a human head. Some searching revealed that this bears a striking resemblance to a photographic portrait of the composer Maurice Strakosch. But why is he the serpent? And what exactly is his connection to Rose Kennedy?

Sea Serpent Polka, composed by Moritz Strakosch (-1887). J.H. Bufford, lithographer. Boston and New Orleans, [1850s].

This piece, I think, is a nice example of how the items in the Graphics Division can open up avenues of research as opposed to being the destination or an illustration for your research—it can be the starting point. I have as many questions as I do answers, but it’s been a delightful and fun project to explore.

— Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Material

Mapping Research Trends in the Collections

Maps have always been an integral part of the library’s collections, starting with Mr. Clements’ early acquisitions prior to his gift to the University. Because maps reflect time, place, and author’s intent, some research themes can prove more elusive for older maps—for instance, the representation of two important communities on maps: Native Americans and enslaved Africans. While Native Americans held priority of geographic place and African Americans arrived via forced immigration, both groups endured forms of displacement within the North American space.

Detail from Guillaume Delisle (1675–1726), Carte du Canada (Paris, 1703). Delisle, a geographer in Paris, compiled this map from many missionary reports and other first hand accounts from the region, populating the area around the Great Lakes with Native American place names and identifiable groups.

The location of Native American groups in North America challenged mapmakers, given the seasonal mobility and fluctuating numbers of many indigenous groups. Yet their very mobility meant that indigenous modes of mapmaking and representation had much to offer early French explorers and missionaries, who often recorded these verbal and sometimes performative maps, although physical maps were rarely replicated. Nonetheless indigenous presence, indicated by the appearance of various group names, are a staple feature of French maps of North America from the 17th century onwards.

Some British mapmakers who carried out ground surveys in colonial regions similarly included Native American groups, territories, and aboriginal claims. A focused British interest in the location of Native American groups is displayed in this manuscript map. “A Map of the Indian Nations” was probably prepared for the British military administration at the time of the cession of the transAppalachian territory to the British from the French at the end of the Seven Years’ War, more easily visible in a detail of the area around Fort Loudon.

Willem De Brahm, 1717-ca. 1799], “A Map of the Indian Nations in the Southern Department,” 1766.

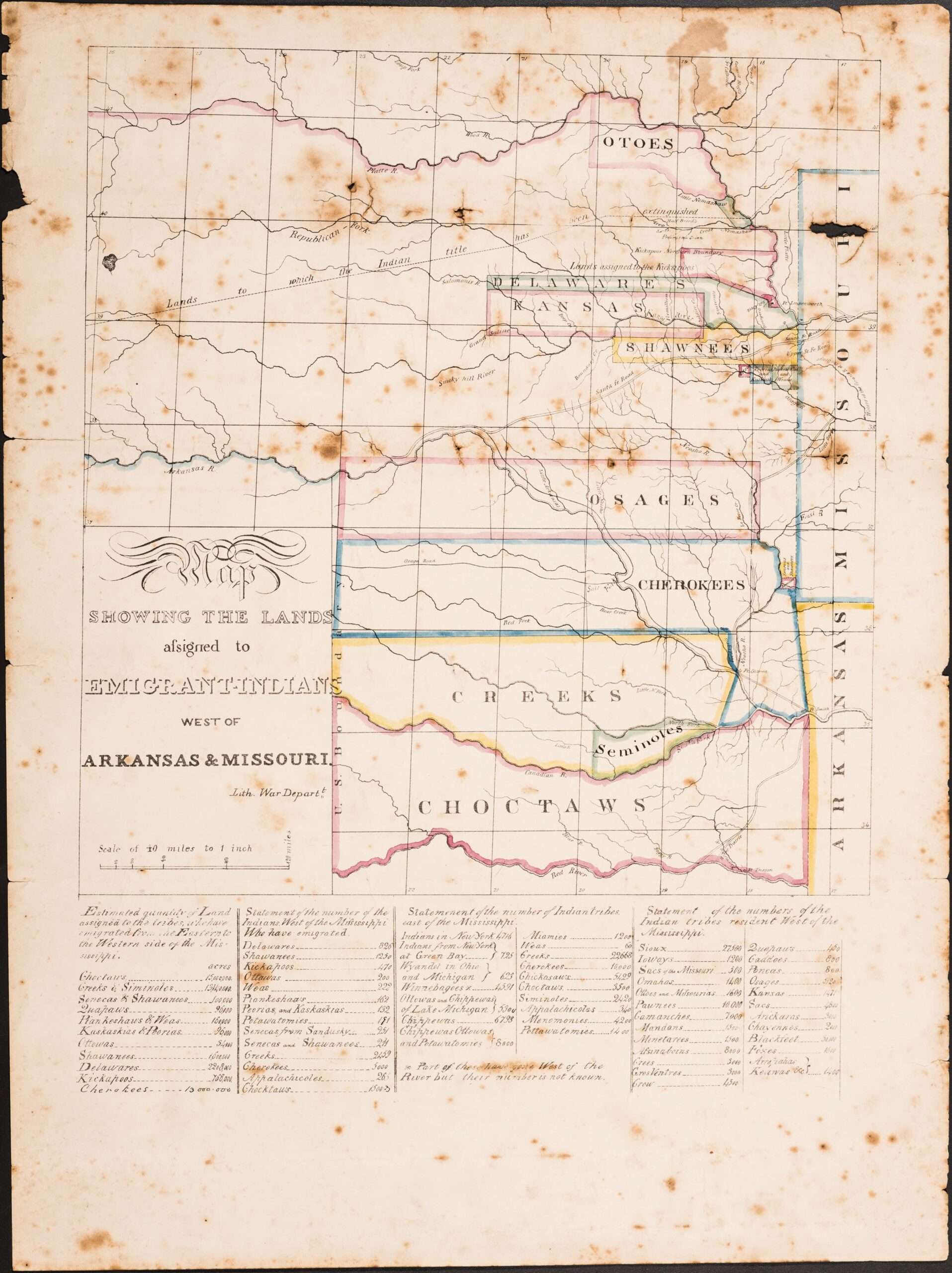

Such maps emphasized the indigenous American presence in regions where European settlers were expand – ing their own footprint. Farmers and settlers of European descent pushed into these western lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, with tragic results for Native Americans. Soon designated as “emigrant Indians” the several groups who spread out in the Southern territory on the De Brahm map were squeezed into a much smaller area in what is now eastern Oklahoma, as shown on the War Department map of 1836 (next page). Colored lines indicated boundaries of lands of 10 displaced Native American groups in the wake of the Indian Removal Act (1830), which authorized the federal government to extinguish all Indian title to the lands in the deep South, and 60,000 souls set out on the Emigrants Walk (or Trail of Tears).

Map Showing the Lands Assigned to Emigrant Indians West of Arkansas & Missouri, produced by the United States War Department ([Washington, D.C.], 1836).

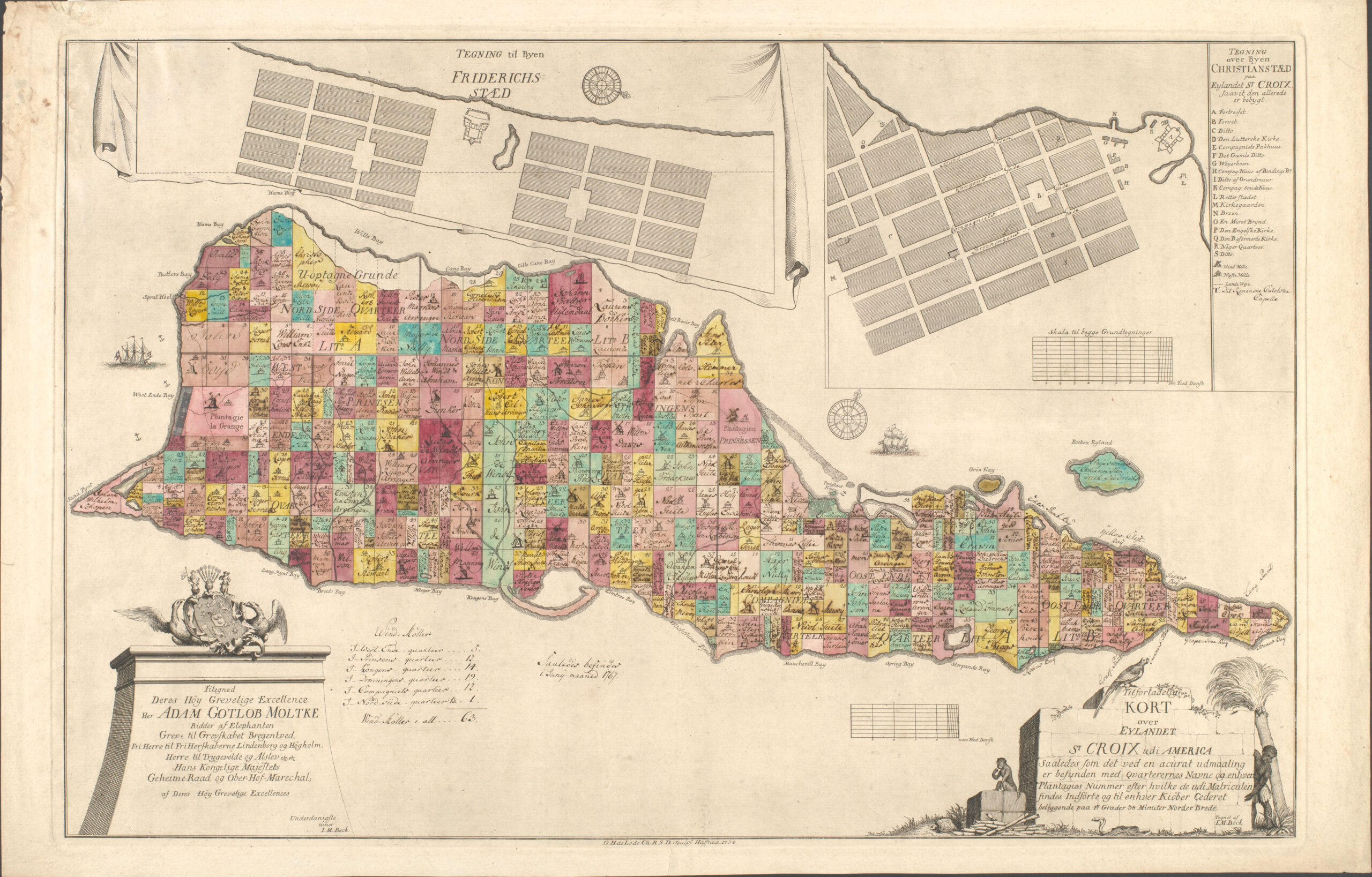

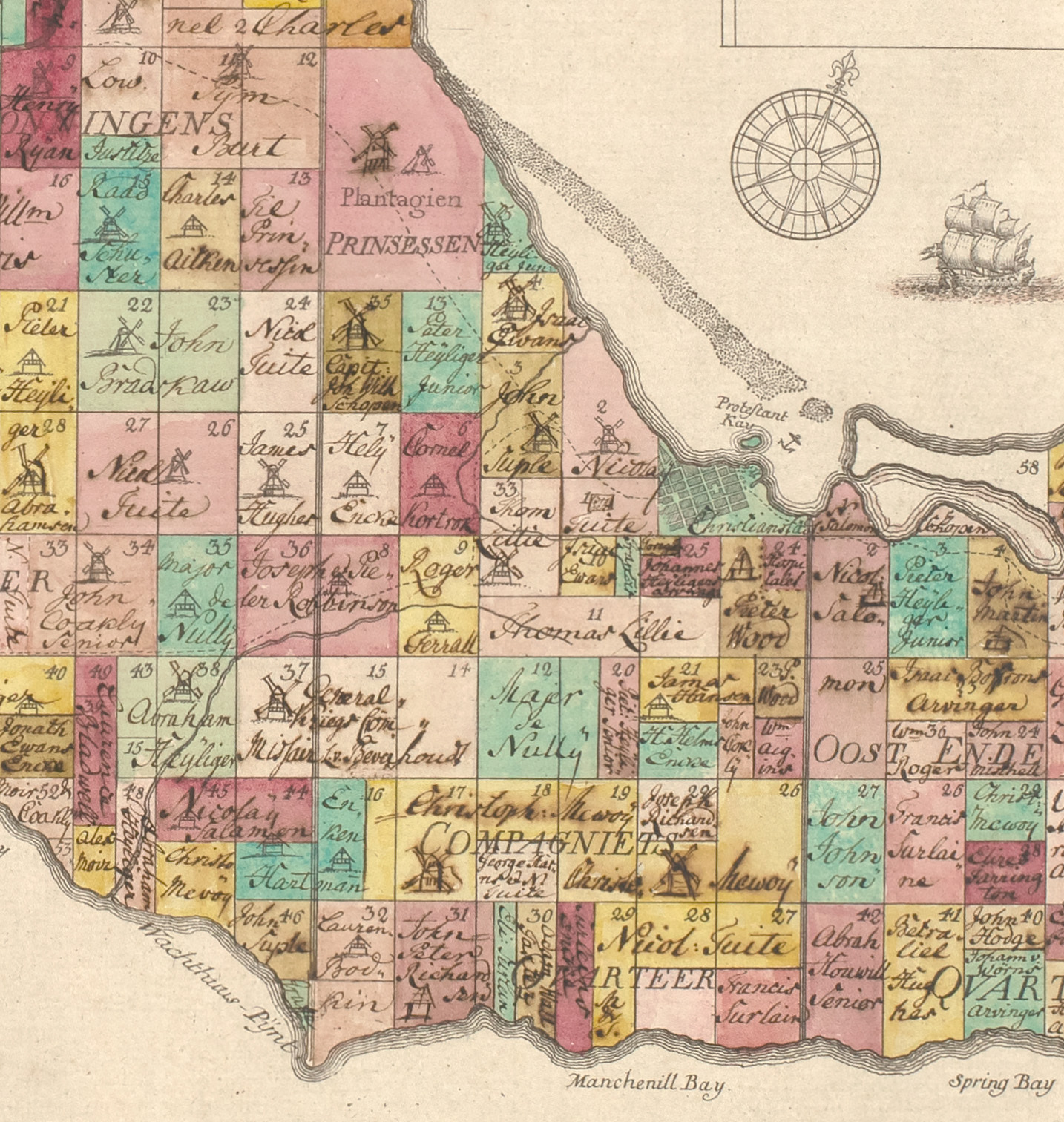

While Native Americans were pushed westwards, forced emigration peopled North America and the Caribbean islands with enslaved individuals. Despite or perhaps because of fears of the growing Black population, the African American presence as forced labor on plantations in the American South or the Caribbean islands was rarely visualized. However, one can discern the size of a plantation and extrapolate the number of slaves required to work in the fields or process sugar (the main export from the islands) from the plantation surveys frequently executed on the islands. A recent research project looked closely at the island of St Croix, a Danish colonial holding, and the depiction of two types of mills used for crushing the sugarcane: wind and animal driven. These mills were built and operated with Black labor, as the cartouche shows. The detail reveals the various sizes of plantations and the number of mills on each, a determining factor in the value of the holdings.

Hidden narratives of race, culture, and space lie under our noses as we study maps. Recent research on one of the Library’s prize atlases has illuminated a link to an annual celebration of historical events In San Pedro Huamelula, Mexico, in which the indigenous Chontal people reenact the invasion of Lan pichilinquis — the Chontal term for “pirates.”

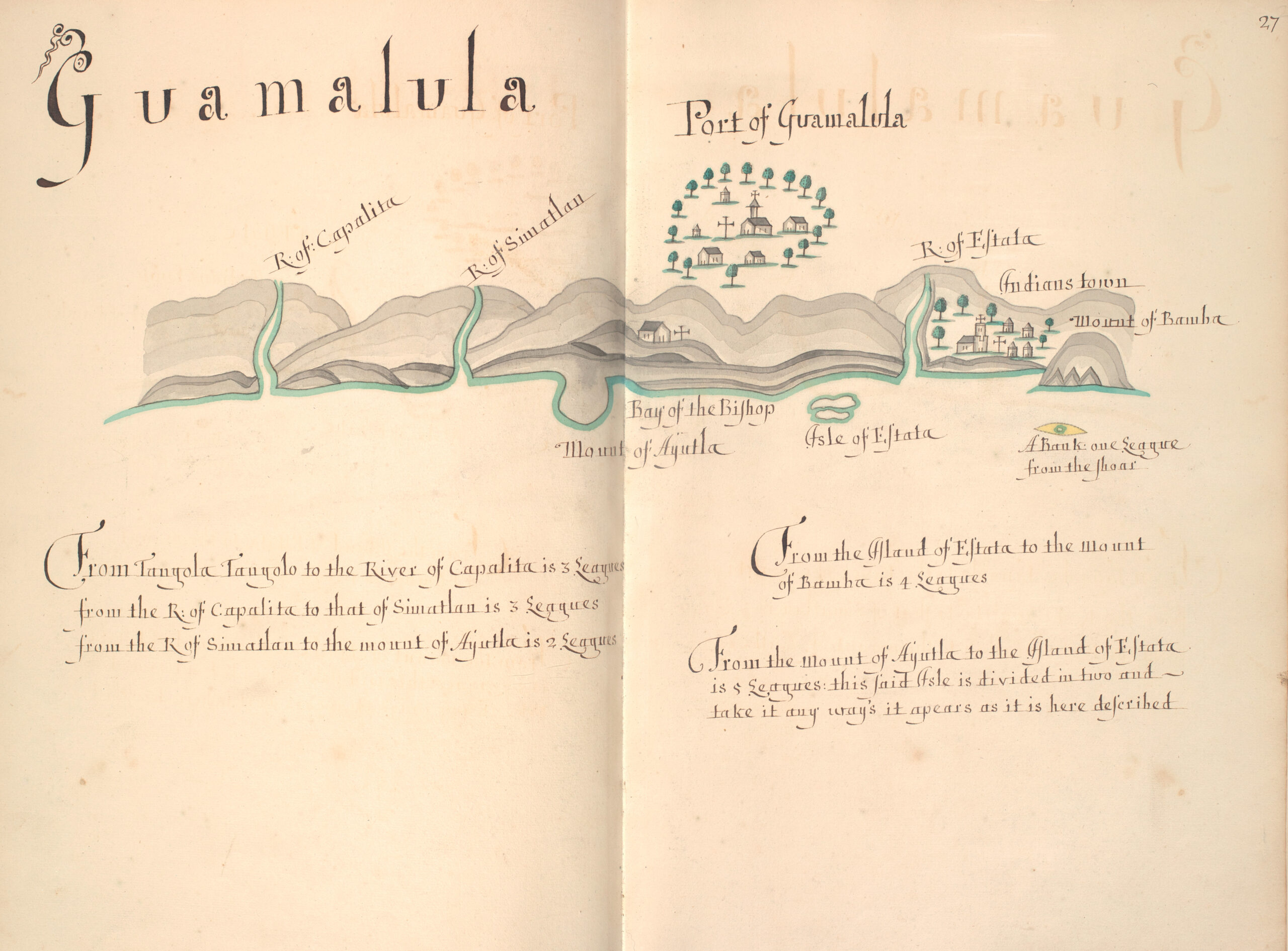

The pirates who invaded Huamelula may be linked to the buccaneer source of the one of the Library’s prize atlases: English chartmaker William Hacke’s atlas of 1698, a volume of 184 manuscript charts of the Pacific coast of America, one of at least 14 editions of this atlas produced in the 1680s and 1690s. The maps in the atlas were based on charts seized by English buccaneers in 1680 from a Spanish ship which were then requisitioned for their own raids on settlements up and down the Pacific coast, from Acapulco to Chile.

Throughout the Hacke Atlas (officially titled, “From the Original Spanish Manuscripts & our late English Discoveries A Description of all the Ports Bay’s Roads Harbours Rivers Islands Sands Shoald’s Rocks & Dangers in the South Seas of America,” hence the commonly used abbreviated title) are over a dozen brief references to various indigenous groups along the Pacific coast, noting who was friendly or hostile to the Spanish or English. Most of these “ethnographic” details do not appear in the original Spanish chart, as Spanish seafarers could typically rely on safe ports and bays controlled by the Spanish Crown; but competing English sailors were always concerned with the precise location of freshwater sources and isolated bays where ships could replenish and careen.

Jens Michelsen Beck, Tilforladelig Kort over Eylandet St. Croix Udi America ([Copenhagen], 1754)

Folio 27, “From the Original Spanish Manuscripts & our late English Discoveries A Description,” by William Hacke, 1698. Guamalula is present day Huamelula on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

On folio 27 of the Hacke Atlas, the Chontal community is glossed “Port of Guamalula” on the coast, although its location was and is inland; it is termed “Pueblo,” or town, on parallel Spanish atlases. Archaeological surveys have confirmed that this was the Chontal community’s original location, before pirate attacks forced the inhabitants to resettle further inland in the late 17th or early 18th century. This displacement is performed in the choreography of Huamelula’s annual reenactment, in which traditional Black characters may represent runaway enslaved Africans who sided with the Chontal to fight and repel foreign invaders. The roles of the reenactment festival echo historical identities of Chontal, pirates, and slaves—three disenfranchised but numerous groups who operated on the periphery of the Spanish Empire in a network of of competitive alliances, vying for land and trade.

The importance of using the past to understand the present cannot be underestimated. To quote Clements researcher, Danny Zborover, 2020–2021 Mary G. Stange Fellow, who brought the connection between the Hacke Atlas and the indigenous Chontal inhabitants of Huamelula to light and life: “by integrating archival research with interdisciplinary fieldwork and community outreach, the Clements Library’s Hacke Atlas and similar sources open a window into a fascinating yet untold story, one in which the Chontal and other Indigenous people contributed directly to the formation of the early Transpacific Modern World.” To paraphrase the ancient writer Cicero, our lives are woven from the threads of memory of previous times and peoples.

— Mary Pedley

Assistant Curator of Maps

Recent Acquisitions

Manuscripts

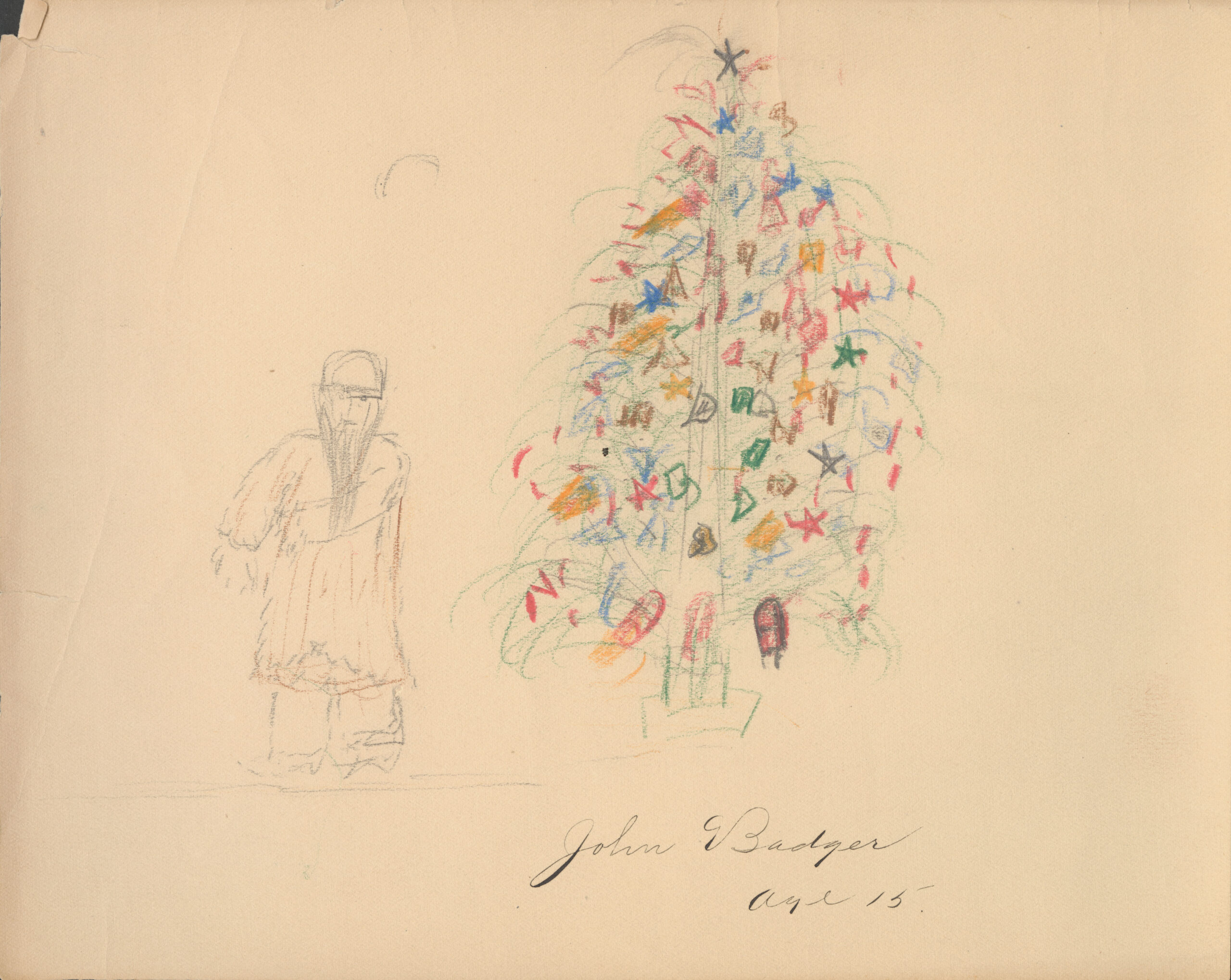

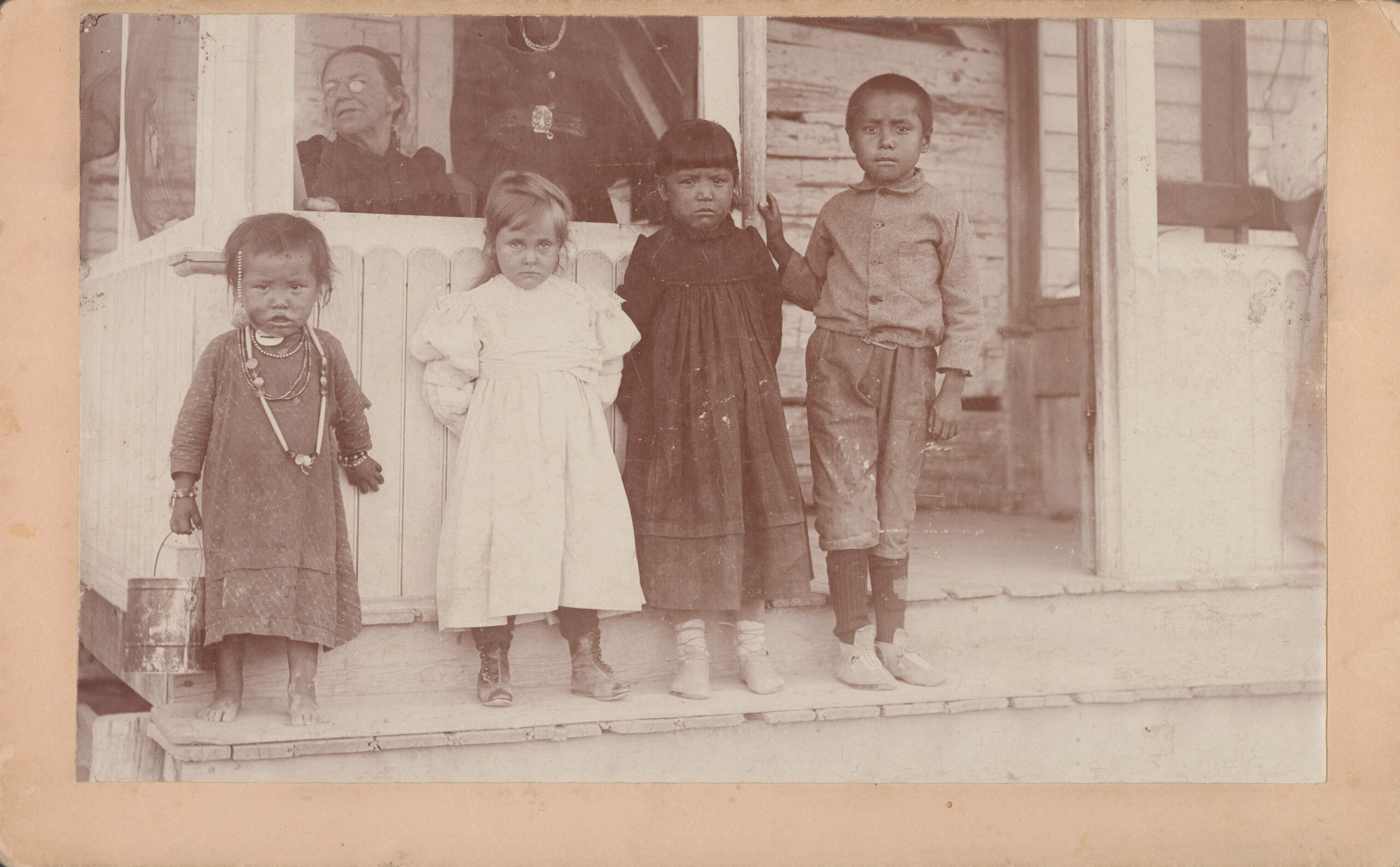

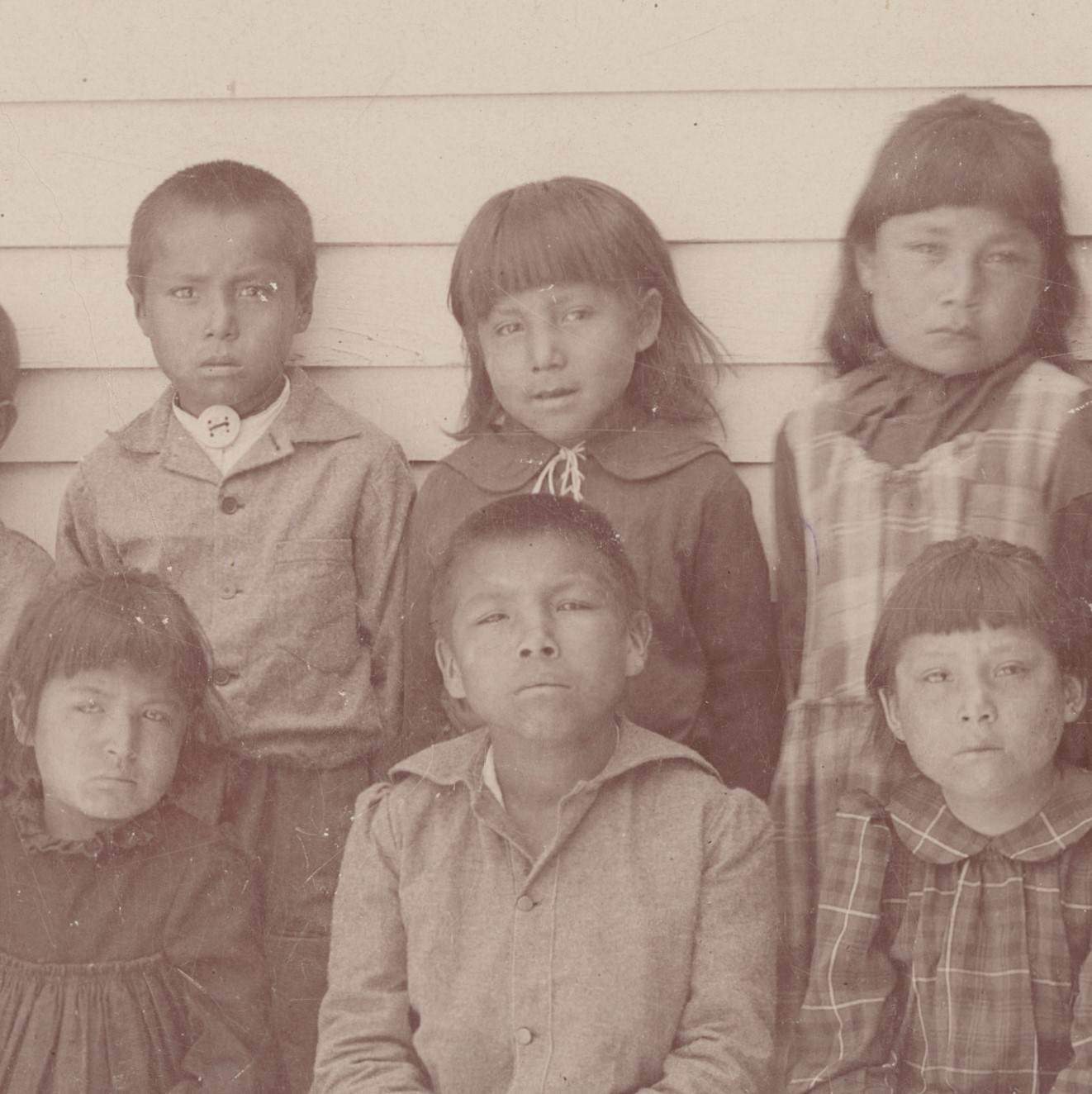

The Clements recently acquired the 19-item Crow Creek Agency Collection, focusing on a Native American boarding school in Crow Creek, South Dakota. Included is a program for the 1892 Christmas celebration, which lists songs and recitations performed by the students, providing a glimpse of student life at this boarding school and how American culture was represented and taught.

Drawing by Crow Creek boarding school student John Badger, age 15.

Evocative student work accompanies the collection. There are eight letters from students who shared their experiences at the Christmas celebration. Many of them wrote about the presents they received and highlighted the week spent at home with family over the holidays. The collection also includes geometric drawings and collages, examples of how these children expressed themselves in moments of forced cultural assimilation that demonstrate how art can help us think about trauma and its relationship to heritage.

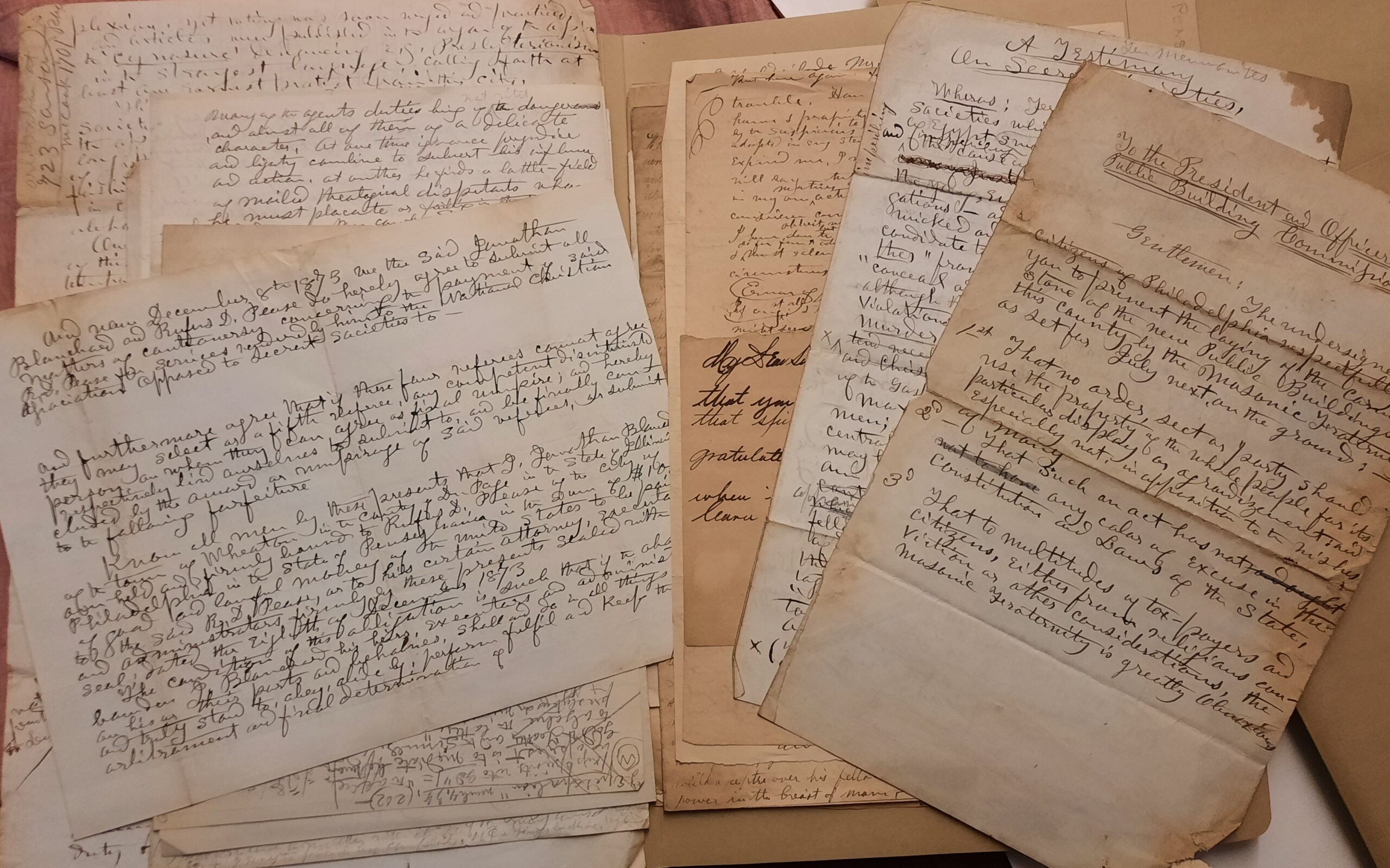

One of the larger recent acquisitions is a collection of papers of Rufus Degranza Pease, including letters, a diary and writings, printed material and more. Pease was a graduate of Willoughby Medical College in 1845, and became an itinerant lecturer on a variety of topics, including astronomy, geology, health, physiognomy, phrenology, and free thought. Following the Civil War, he lectured for the National Association of Christians Opposed to Secret Societies, focusing on Freemasons, Knights Templar, the Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, and others. Later in his life he became a doctor of physiognomy in Philadelphia where he resided until his death in 1890.

A selection of draft documents from the papers of Rufus DeGranza Pease.

Much of the correspondence to Pease is from fellow peddlers of educational services and instructive lectures in the Midwest. They collaborated and traded information and advice on travel routes, discussed which communities were receptive to their services, and how much could be charged for lectures and classes.

Other letters written by Pease are filled with fury, directed toward Mormons among others. Pease was an abolitionist and anti-slavery advocate, though he raged at Lincoln for the suspension of habeas corpus in 1863. He also believed that he was being persecuted, seemingly somewhat justified by his imprisonments for “seduction and fornication.” He wrote during one imprisonment in October/ November, 1863: “For my part I have seen the hand of Providence in the matter from the first, and cannot doubt that I am bruised for the benefit of your community. No silly and contemptible malicious charge against me of insanity, even though bolstered up by sap headed drug and quack medicine peddlers of Berlin [Wisconsin] as elsewhere, will avail against the true and right…The charges they had diligently circulated for months about me were fornication, even going so far as to specify a person, and also seduction. But finding they could make no headway in that direction immediately commenced to cuttlefish under a wholesale and cold-blooded charge against me, even to indict me of partial, if not entire insanity.”

During his later years in Philadelphia, Pease earned money by providing phrenological and physiognomical advice. He conducted a mail order business, soliciting letters from clients, which arrived with enclosed photographs, posing questions such as: Will I be a good candidate for the priesthood? What type of career should I pursue? For the exorbitant fee of $10, Pease would provide answers by return mail, presumably based on physical characteristics exhibited in the photographs.

Printed materials include the only issue that Pease ever produced of the Journal of Man, published by Rentoul in Philadelphia in 1872, as well as a variety of lecture and course advertisements, synopses and tickets, flyers, and circulars.

Books

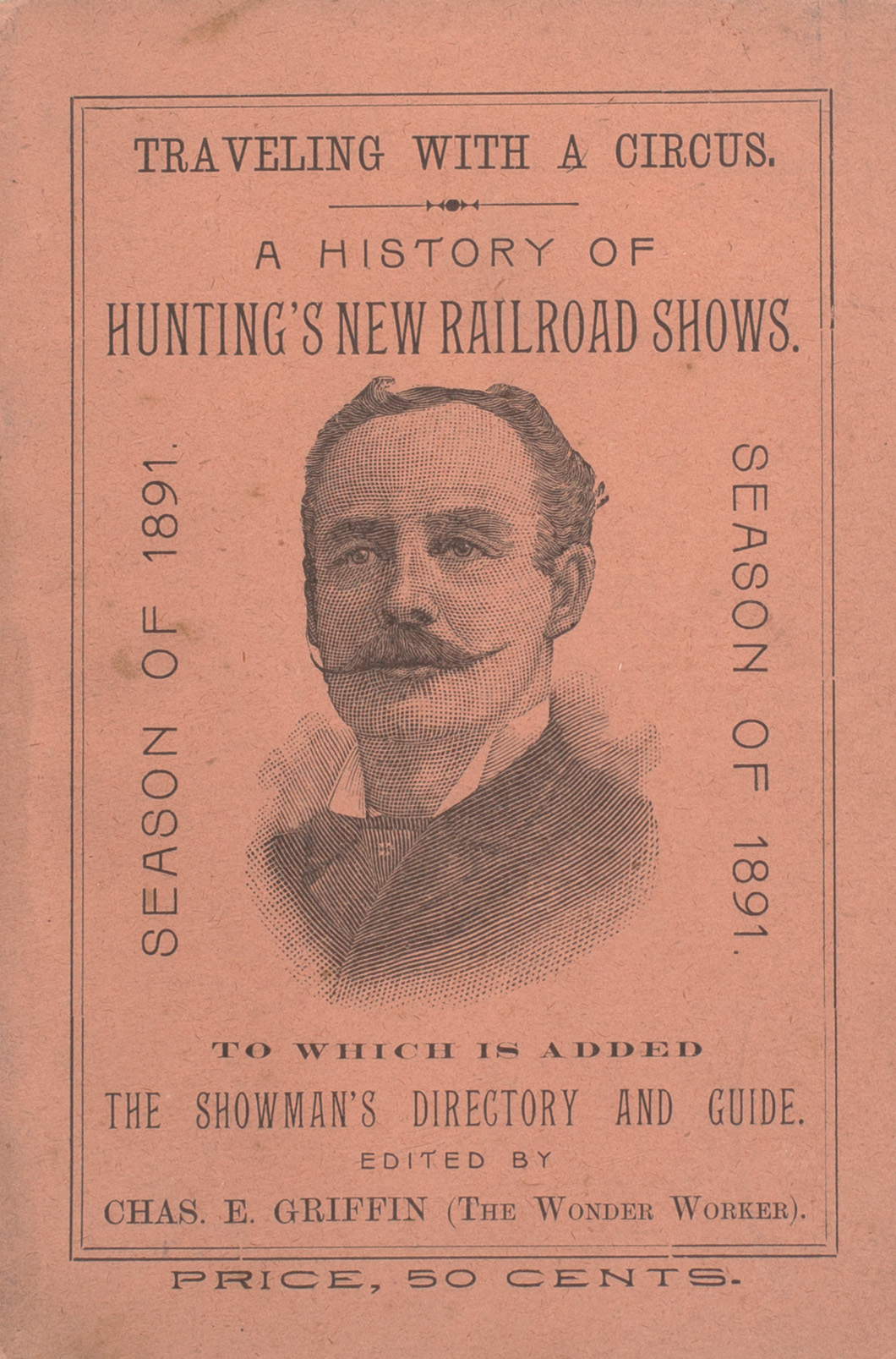

The route book for 1891 features a cover portrait assumed to be Robert Hunting (ca. 1842–1902), “Sole Proprietor and Manager” of Hunting’s New Railroad Shows.

New to the Book Division are three pamphlets related to Hunting’s New Railroad Shows, or Hunting’s New United Monster Railroad Shows, a circus traveling by rail car to locations around the United States. The pamphlets are referred to as route books and contain accounts of the seasons of 1891, 1892, and 1894. Each route book starts out with a list of the performers and support staff who traveled with the circus, including: cooks; musicians and other performers; an advance team that traveled ahead to take care of the advertising and to set up the tents; and caretakers for the animals, among others. The heart of each pamphlet is the “Author’s Diary,” comprised of snapshots of stops on the season’s itinerary, recording the location, the population of the towns, the railroads taken to get there, the weather, and any notable events. The financial success of the show is often noted—“bad business,” “fair business,” “good business,” or “big business” (the maligned Easton, Pa. keeps up its reputation of being a “‘bum show town”). The entries provided vivid accounts of the challenges of managing a traveling circus—wrangling people, equipment and animals; the sometimes gruesome injuries sustained by performers; railroad mishaps; and the revolving-door entrance and exodus of performers along the way.

An example from 1892:

Brewsters, N.Y., May 31.— First real

“circus day” of the season. During

the parade this morning a wild bull

made his appearance and stampeded our lady and gentlemen

riders. Prof. Mohn led the enraged

beast a wild chase down a narrow

alley, and Jeanne Earle created a

sensation by making a daring leap

for life from the back of her fiery

steed to terra firma. Where the beast

came from or where he went is an

unsolved mystery. This is the home

of a great many retired showmen.

Mr. Henry Barnum, who is now

connected with the Forepaugh

Show; Mlle. De Granville (Mrs. Dr.

Knox) and Lew Baker, an old time

boss canvas-man, were visitors.”

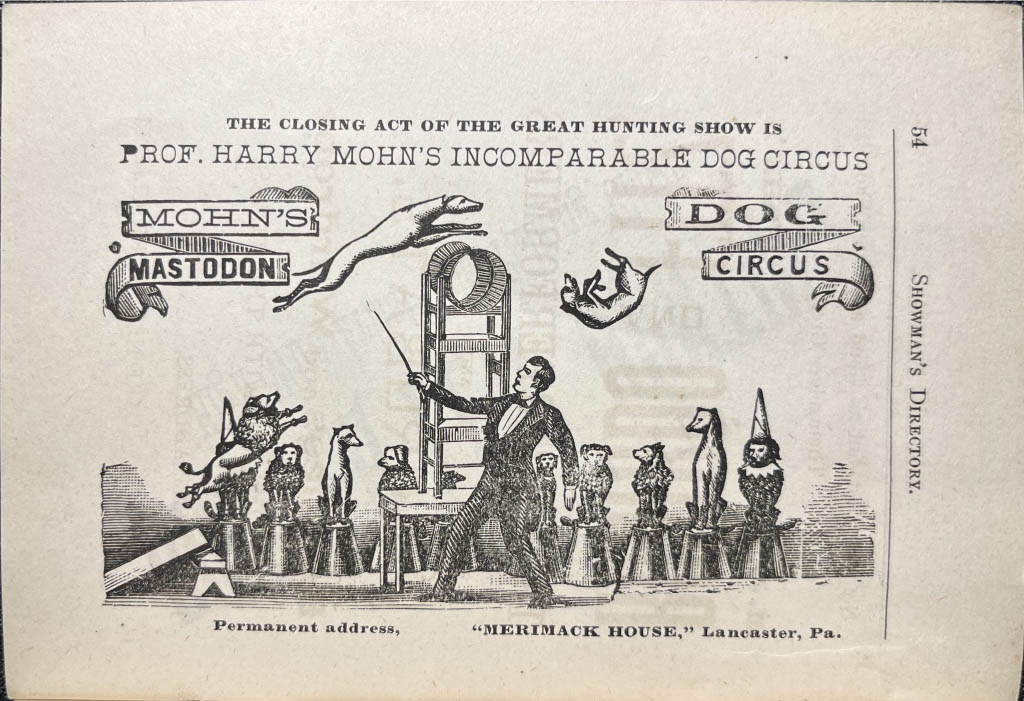

One of the acts advertised in the 1891 guide was “Professor” Harry Mohn’s dog circus. Mohn was featured in an entry describing an eventful stop in Pennsylvania: “A Duncannon loafer stole one of Prof. Mohn’s trick dogs after the night show, but Harry succeeded in getting the dog back before he left town. Harry Smith was kicked in the groin by a tough. It will lay him off for several days.”

Two of the pamphlets include a “Showman’s Directory and Guide,” compiled annually. The Directory listed contact information for performers and service providers who might be needed by a traveling show. If you required new balloons, or ran out of circus lights, or were in need of canvas, magic lanterns, or a taxidermist, contact information is available! There are listings for engravers, lithographers, printers, tightrope walkers, clowns, jugglers, and musicians—the panoply of services required to keep the show on the road. The collection reveals the cooperation that existed among similar outfits, who traded information and provided mutual support.

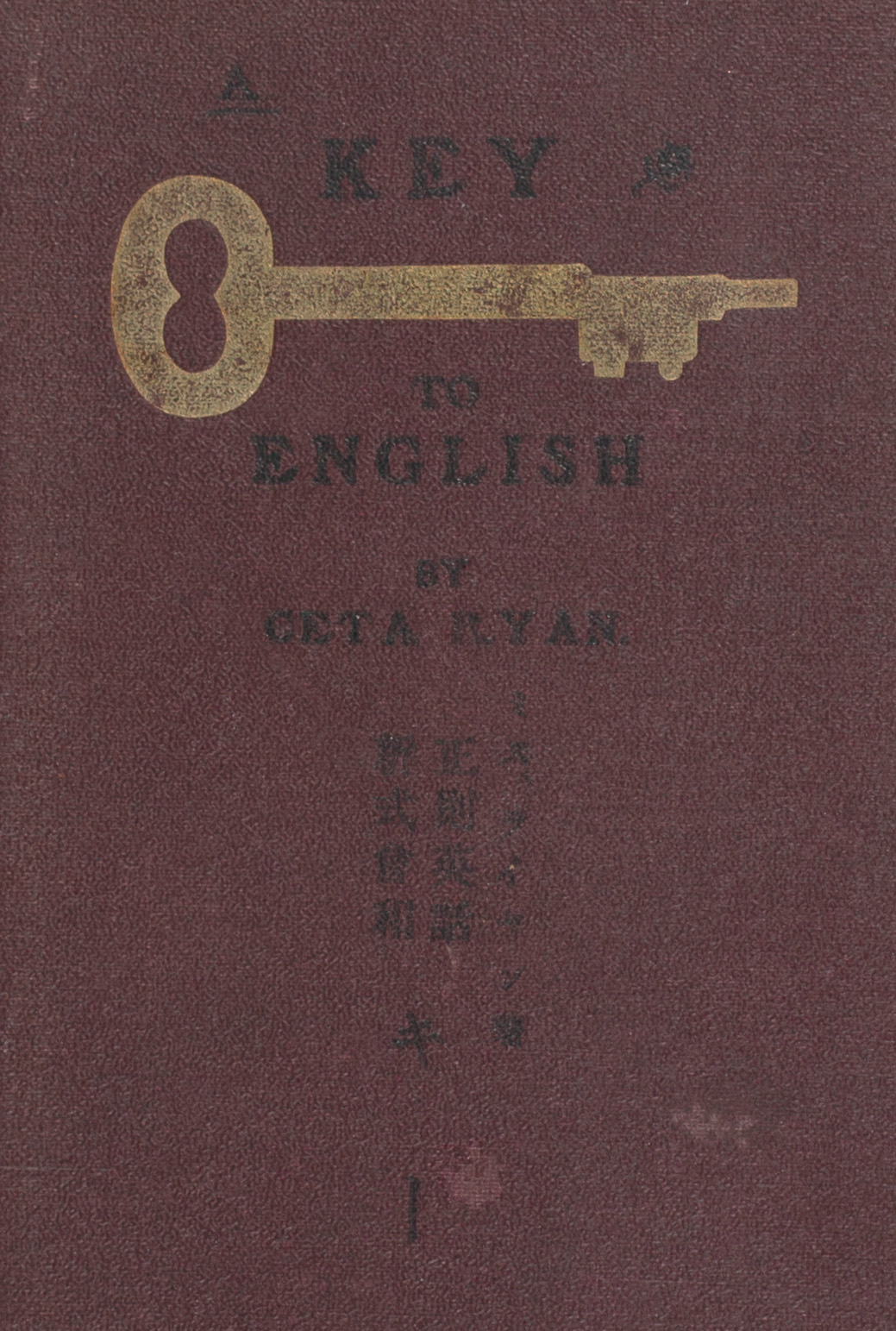

Also recently acquired, A Key to English is a textbook produced by Ceta Ryan to help Japanese immigrants in California learn English. An imprint from 1906 San Francisco is a rarity in itself, given the earthquake and subsequent fire which burned much of the city. But the volume is interesting in several other aspects. The text is printed in both English and Japanese, which was a complicated task for the printing technology of the era. Information inside the back cover indicates that this book was owned by someone who spent time in the internment camp in Poston, Arizona, during World War II, revealing that it had a fairly long life in readers’ hands and somehow wound up in a carceral setting.

Little is known of the author of A Key to English. Census records list a woman named Ceta Ryan (born ca. 1865), a private teacher residing in San Francisco as late as 1940 along with a lodger born in Japan. We have no information about the owners of the volume, or who penciled the inscription on the inside back cover.

Books

Recently arrived in the Graphics Division’s growing collection of ephemera, is a fascinating tiny redware souvenir—measuring 3.5 cm—made to look like a soldier’s canteen and to commemorate the Battle of Gettysburg. On one side is affixed a photograph of a woman named Jenny Wade, who lived in Gettysburg with her mother and was killed during the battle on July 2, 1863. Wade and her mother lived in the middle of the town of Gettysburg, and when the fighting started, moved to the home of a relative. One morning while Wade was kneading dough to make bread for Union soldiers, a Confederate unit began firing at the house. A musket ball passed through the door and killed her. Famously, the day after her daughter died, her mother finished baking the bread that her daughter had started when she was shot and killed, and gave it to the Union soldiers to feed them.

And on the other side of the souvenir is a picture of a man named John Burns, another famous civilian folk hero of Gettysburg. While Burns was almost 70 when the battle began, he was eager to fight with the Union soldiers whom he admired. Burns left his house with an old musket, a top hat, and frock coat and joined in with a Union regiment marching by. He borrowed a rifle from a wounded soldier and fought throughout the Battle of Gettysburg with several different units. Burns was wounded several times, and he achieved fame as a volunteer civilian who pitched in to help the Union cause.

The large amount of iron oxide present in the clay used for redware gives the unglazed earthenware its striking color.

Next is a group of five photographs from the Montana Industrial School for Indians, a boarding school in west central Montana, about an hour or so west of Billings. Unitarian Universalists opened the school in 1886, and it operated for a decade before the federal government discontinued funding and it was forced to close. These evocative images are of the students, who were mostly Crow Indians.

Looking closely at details of these photos, one can spend time noticing the children’s expressions and reflecting on their experiences.

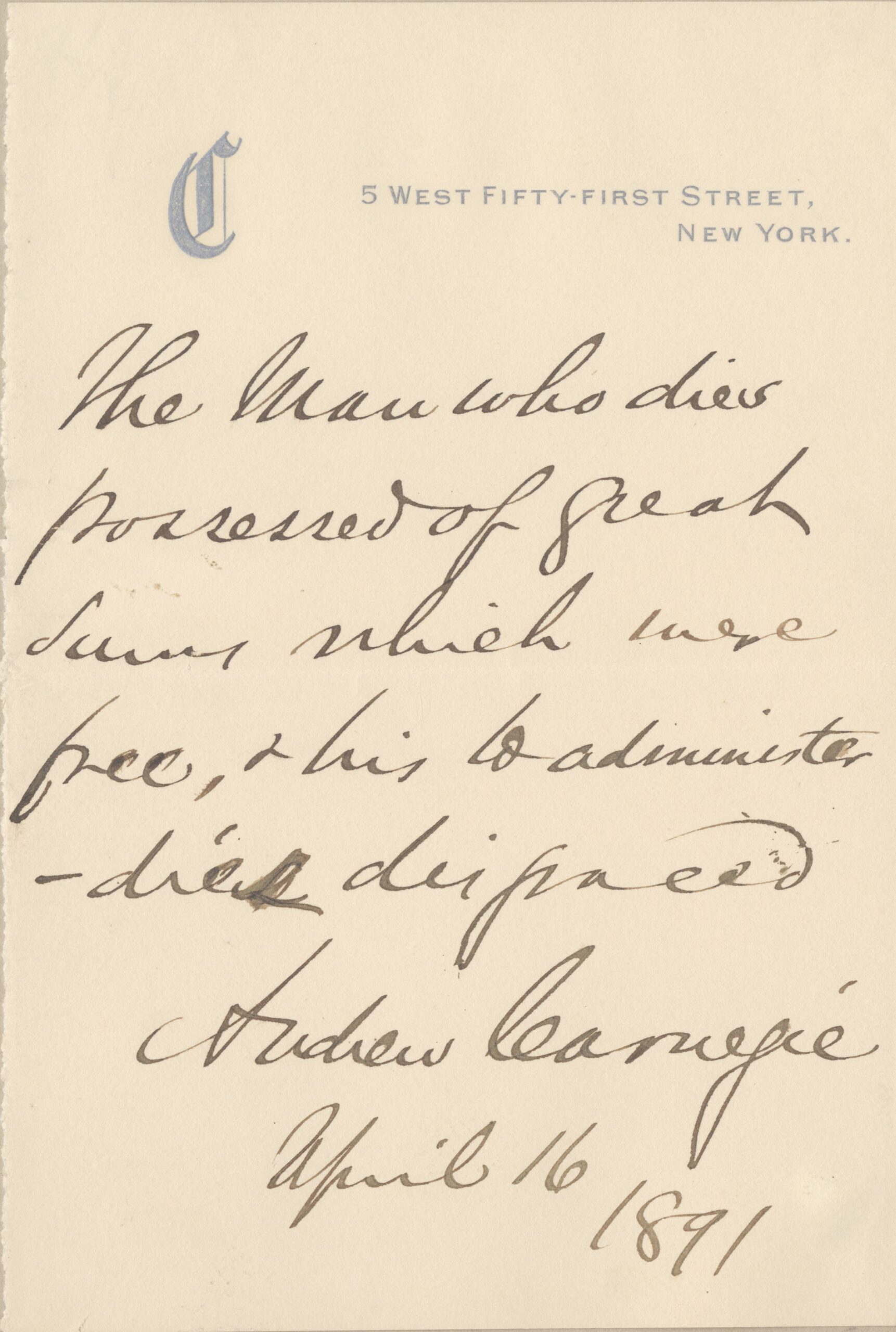

Philanthropy Builds the Archive and is Recorded There, Too

The Centennial is a celebration of the William L. Clements Library, but it is also a story of the philanthropy of the people who have bolstered the building, collections, and programs through their generosity. This, of course, starts with Mr. Clements himself. Influenced by U-M Professors Thomas M. Cooley and Moses Coit Tyler, Clements had a love of American history and culture that led to his collection and eventual donation of materials. His vision included the funds to build a magnificent facility to house the collection designed by Albert Kahn. While these gifts were extraordinary, Mr. Clements also participated in a variety of other philanthropic causes, but did not offer an explanation behind his gifts. We lack insight into the reasons behind his philanthropy and what influenced his donations—whether it was part of the culture of the time, a sense of duty, or other personal or moral imperative.

Jens Michelsen Beck, Tilforladelig Kort over Eylandet St. Croix Udi America ([Copenhagen], 1754)

In November we celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Clements Library Associates (see sidebar). In addition to a party to mark the celebration, I also hosted 2022 Norton Strange Townshend Fellow Amanda Moniz on the online program Clements Bookworm to discuss her research into philanthropy. One hundred years ago the Clements Library didn’t have any professional fundraising staff let alone research fellows looking for evidence of philanthropy in the archives. The beautiful thing about the archives is that there are innumerable layers of information awaiting new questions to be asked.

As I contemplated the Centennial year and my role within the Clements, I started to think of the Development and Communications Division as a connector of the past, present, and future—perhaps not unlike Mr. Clements. We have modern tools in social media to help highlight stories in the collections for the public and we seek out gifts that ensure that the Clements Library will be here well into the future. One of Dr. Moniz’s research sources was the Divie and Joanna Bethune Collection (1796–1853), but that isn’t the only place we find philanthropy in the archives.

Benjamin Bussey (1757–1842) was a Revolutionary War veteran, excellent businessman, and philanthropist. The Benjamin Bussey Collection at the Clements holds letters from acquaintances, organizations, and even strangers asking Bussey for loans and charity. He responded positively with gifts to a wide range of organizations.

Those seeking to influence public perception have long known that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” and the inexpensive availability of trade cards and photos in the 19th Century helped to make them a viable fundraising tool. We have images of social activists Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) and Sojourner Truth (1799–1883) that were sold to advance their work. Some who purchased these cards admired the activists and their causes enough to display their photos in family albums.

Other fundraisers used images to support the institutions where they worked. For example, we see the emergence of a professional fundraiser in Reverend Henry Leonard, the “financial agent” of Heidelberg College (now Heidelberg University) in Tiffin, Ohio, for thirty-two years. Leonard posed for a series of photographs documenting his “fishing trips” to raise money for the University. He was well-known and beloved for his work and his story lives on in the Maxson Ephemera Collection.

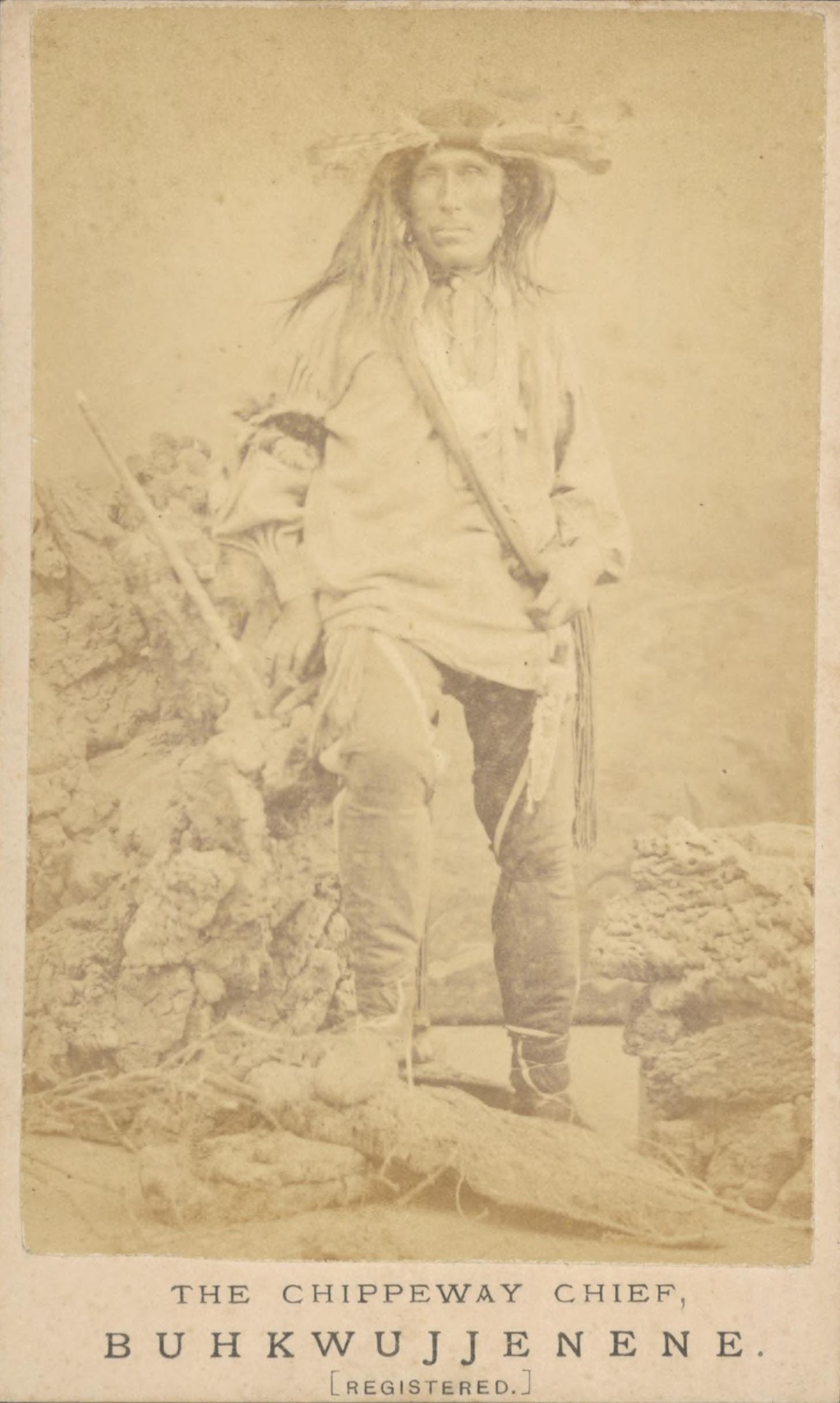

Photograph taken in 1872 during Rev. Edward Francis Wilson (1844–1915) and Ojibway Chief Buhkwujjenene’s visit to England while fundraising for Shingwauk Indian Residential School. Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography. Gift of Tyler J. and Megan L. Duncan.

Henry Leonard re-enacted his “fishing trips” for the camera. Maxson Album #14, gift of Jerry and Charlotte Maxson.

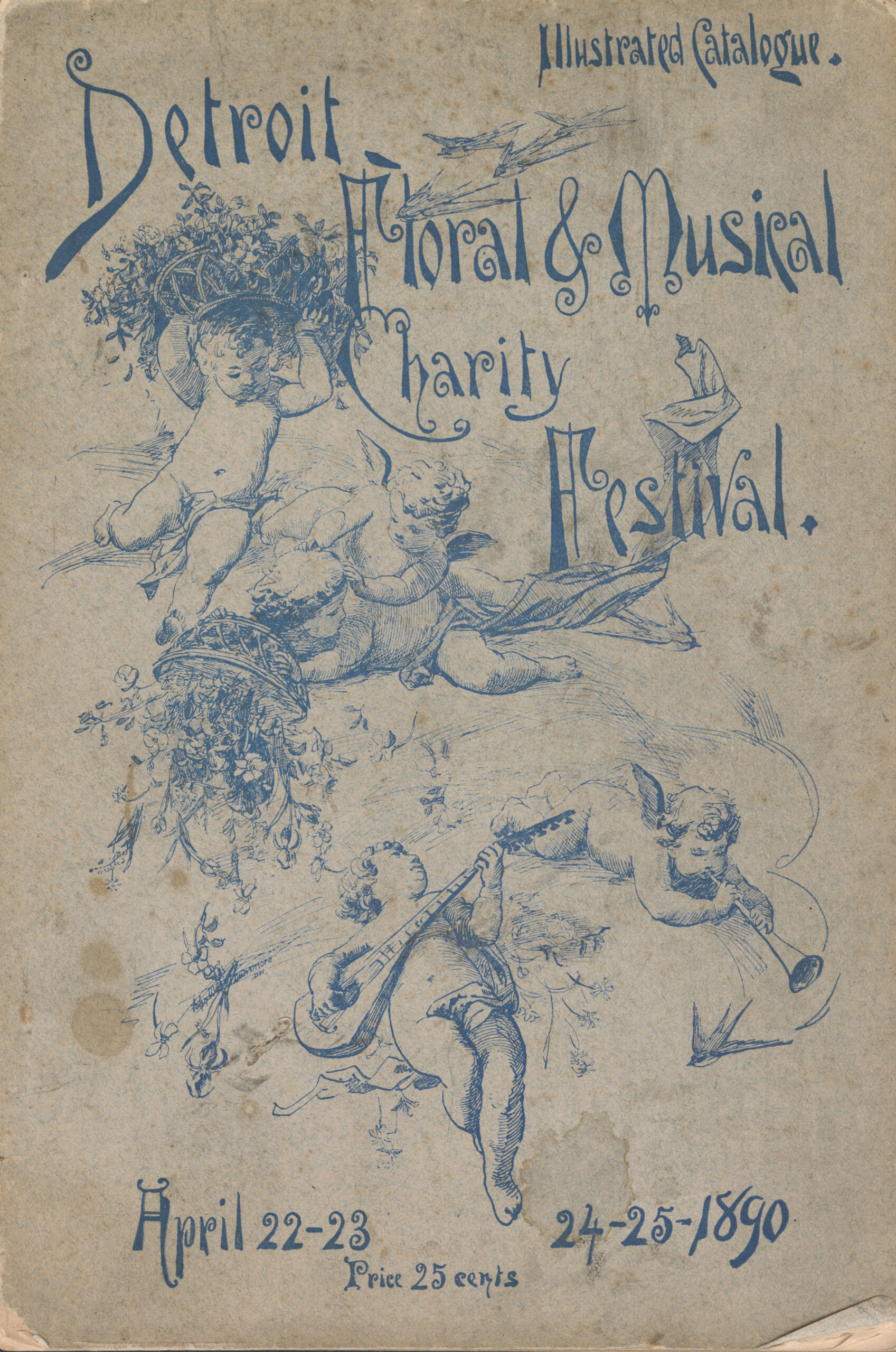

A richly illustrated catalog of the floral and musical festival in Detroit, Michigan, records the efforts of the many volunteers who in 1890 enjoyed the camaraderie of planning a community event to raise funds for many causes around the city. We learn that at the 1889 event, nearly 35,000 people attended, garnering $11,000 that was split among twenty-one charities.

Did you notice that the illustrations provided were also all donations? Philanthropy at the Clements Library has been woven into all we do since the inception of the institution. I hope that I serve this institution in a way that builds our foundation for the next century by valuing your partnership in this endeavor.

— Angela Oonk

Director of Development

Illustrated Catalogue of the Floral and Musical Charity Festival (Detroit, 1890). Gift of Martha Seger.

Announcements — Winter/Spring 2023

New Staff Members

Kayla Robinson joins the Development Department as the Marketing Coordinator and oversees social media, updates the website, and creates a variety of print and digital marketing pieces.

In a newly created position as a Development Generalist, Helen Harding fosters philanthropy through mailings, provides information and stewardship to donors, and helps plan special Centennial events.

Heather Alphonso lends her experience to the reception staff, greeting researchers and visitors and helping with administrative tasks.

Appointments

In July 2022, Clements Library Director Paul Erickson was officially announced as the president-elect of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, the primary scholarly society for historians studying the era between 1787 and 1860. His term will run from July 2023 to July 2024. He will be the first representative of a library or archive to hold the SHEAR presidency.

Welcome!

The Clements family welcomes its youngest member—Lucy Obata Goeman was born on February 23 to Emiko Obata Hastings, Curator of Books, and her husband Bill Goeman. Lucy’s own interest in books, like Lucy herself, is nascent but growing fast!

Clements Library Associates

The Quarto No. 15 in March of 1948 introduced the creation of the Clements Library Associates: “It is the University’s desire that our riches shall be more effectively shared with those who are concerned about American history and tradition. Therefore, the Regents of the University of Michigan, at their meeting of October 24, 1947 established The Clements Library Associates…”.

For the past 75 years, the Associates have fulfilled their original purpose of “increasing the collections and resources of the Clements Library and of broadening the scope, services, and usefulness of the Library.” Associates give of their collections, money, time, and intellect making the Clements the world-renowned library that it is today. Anyone who donates to the Clements Library is a member of the Clements Library Associates. To mark the 75th Anniversary, we celebrated on November 17, 2022, at the Clements Library.

Paul Erickson, Randolph G Adams Director of the Clements Library; Laurie McCauley, Provost; and Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman of the Clements Library Associates Board of Governors.

Debra Schwartz and Howard Brick peruse the pop-up exhibit highlighting acquisitions made possible by the Associates.

Carol Virgne, Randi Kawakita, Tsune Kawakita, and Charlotte Maxson.

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Santa J. Ono, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Kristin A. Cabral, Candace Dufek, Charles R. Eisendrath, Derek J. Finley, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Troy E. Hollar, Martha S. Jones, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, James E. Laramy, Thomas C. Liebman, Richard C. Marsh, Janet Mueller, Drew Peslar, Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Peter Heydon, Chair Emeritus. Joanna Schoff.

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Designed by Savitski Design, Ann Arbor

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Sarah Hubbard, Okemos; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Santa J. Ono, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

![gr-uncat-[clements library] leon makielski ca. 1920s](https://clements.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/gr-uncat-clements-library-leon-makielski-ca.-1920s-scaled.jpg)

On the Cover

Leon Makielski (1885 – 1974) was an artist from southeast Michigan who specialized in landscapes and portraits. He developed an Impressionist style while studying in Paris, and later taught at The University of Michigan School of Art & Design.