TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

Eye of the Microbe

Maggie Vanderford

Librarian for Instruction and Engagement

The golden age of microbiology during the 1880s–90s signaled a landmark shift in popular awareness of human relationships to the microscopic world. As French chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) and German physician Robert Koch (1843–1910), among others, rapidly identified the bacteria responsible for infectious diseases like cholera and tuberculosis, such scientific discoveries quickly took hold of the public imagination. By the end of the century, the language of microorganisms was part of common public health parlance. It became a given that millions (or billions!) of tiny living creatures, unseen to the human eye, were in fact powerful players in battles with infection or epidemic disease. At the Clements Library alone, numerous medical treatises and manuscripts document this shift. The Thomas Nock Notebooks (1884–1890), for example, include the writings of a Philadelphia medical school student invested in the nuances of the “germ theory of inflammation.”

Despite the swift pace of microbacterial discoveries, there was still significant uncertainty about exactly which kinds (and how many?) of these small lives existed in this invisible realm. Such an immense world of uncategorizable minutiae required new terminology to describe it. The word “microbe,” coined by surgeon Charles-Emmanuel Sedillot (1804–1883) in 1878, was rooted in the Greek terminology for “small” (mikros) and “life” (bios). The concept of the “microbe” became a helpful blanket term with which to describe anything from bacteria to fungi to protozoa to yeasts or viruses. Still today, a microbe can describe any “very small living thing . . . that can only be seen with a microscope.”

The satisfying vagueness of the word “microbe” was useful for scientists who needed wiggle room in providing explanations of infectious phenomena, but even more useful for literary authors and psychologists inspired by the idea of a micro-world. Easier to conceptualize as a character than a million bacterium, microbes inspired a booming print culture of advertisements, treatises, and creative stories imagining the inner lives of microscopic beings.

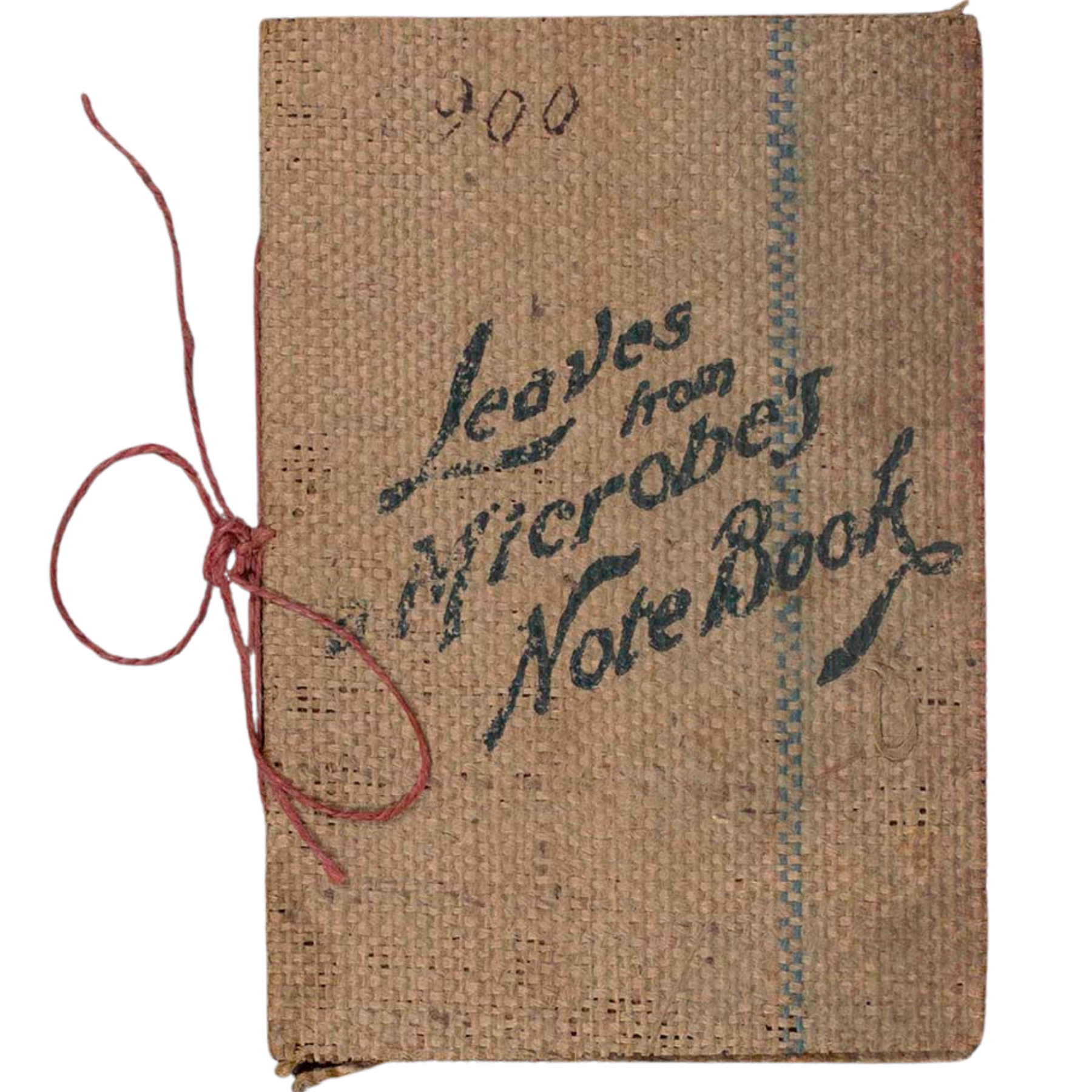

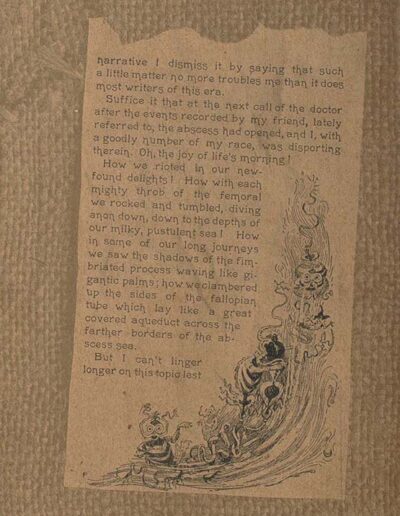

The Clements Library holds one particularly rare example of this print phenomenon, Leaves from a Microbe’s Notebook (Yonkers, 1890), which only exists in one other copy held at the Huntington Library. The striking pamphlet was bound in burlap fabric wrappers and printed on imitation burlap paper, an expensive proposition for what it was—which was a piece of promotional literature for the antiseptic Borolyptol, manufactured by the Palisade Manufacturing Company in Yonkers, New York. The story was narrated by a dramatic (and literarily inclined) microbe, who recounted the tale of his birth and of his role in the formation of a pus-generating abscess. Unfortunately for the microbe and his brethren, the doctor in the story sprayed the abscess with Borolyptol; although the first treatment was not enough to kill them, it had a traumatic effect: “Up to this time I had had a clear conscience and an unimpaired memory,” wrote the microbe. “Later in the day as my senses slowly returned, I became aware that something had happened. Gradually there came to me a recollection of a horrible, blinding, suffocating storm which had swept over us.”

An early 20th-century Borolyptol label indicated that it was “An Ideal Antiseptic and Germicidal Fluid for Internal and External use. Antagonistic to All Disease Breeding Germs.” Image courtesy of Lake Forest College in partnership with the Chicago History Museum.

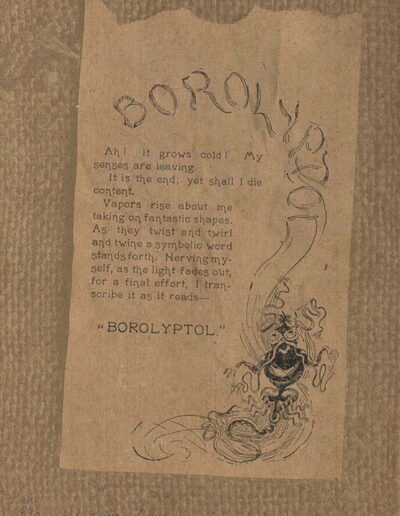

As the story continued, the microbe shared other details about his “race”: they can multiply “exceedingly” at short notice if the occasion demands; their temporality clashes with human chronologies (“With us a day is as a thousand years—more or less”), and so on. The melodramatic ending felt reminiscent of a starlet’s stage soliloquy when the antiseptic returned for the final death blow, and the microbe described his own death: “Ah! It grows cold! My senses are leaving. It is the end; yet I shall die content. Vapors rise about me taking on fantastic shapes. As they twist and twirl and twine a symbolic word stands forth. Nerving myself, as the light fades out, for a final effort, I transcribe it as it reads–“Borolyptol.”

The humorous advertisement was, on one level, a silly and clever visualization for customers who wanted to believe that all infections had a singular, simple solution in the form of antiseptic. On another level, it seriously anticipated real questions that experimental psychologists would ask in the coming decades about the interior life of microbes. The Clements Library holds a copy of experimental psychologist Alfred Binet’s landmark text, The Psychic Life of Micro-Organisms (originally published in New York in 1889; WLCL copy from Chicago, 1897), which detailed the psychological phenomena witnessed in “the lowest classes of being.” Binet didn’t go as far as insisting that microbes thought about long walks on the beach or feeling pain, but remained certain that they experienced some kind of psychological interiority.

In addition to such psychological and philosophical inquiries, American authors such as Mark Twain (1835–1910) were deeply invested in imagining a microbial perspective as a narrative way to investigate human similarities to other creatures. After reading The Story of a Germ Life by H.W. Conn (New York, 1904), Twain began writing 3,000 Years Among the Microbes (1905), “Translated from the original Microbic,” a scientific fantasy novel narrated by a man-turned-cholera germ living among the microbes in a tramp’s body. For Twain, the viewpoint of a microbe helped investigate the ethical dilemmas at stake in sharing the world with an unknown, possibly unimaginable number of organisms, both macro and micro. Famously, Twain left his microbe novel unfinished. Something about the tension between the human and microscopic worlds felt irresolvable to him, and he certainly wouldn’t rely on the easy simplicity of killing them all off with an antiseptic à la Borolyptol.

Although fascination with the microbe, specifically, as a character, a form, and an idea may have emerged in 1878 with the word itself, a compulsion to narrate from the perspective of microbial life has remained throughout the twentieth century. From the Adventures of Jimmy Microbe by Virginia Budd Jacobsen (Chicago, 1937) to the Adventures of Micki Microbe by Maurine Burnham Guymon (1987), I Contain Multitudes, by Ed Yong (New York, 2016), and Me, Microbes, and I by Philip Bunting (Melbourne, Australia, 2021), it is clear that we remain more motivated than ever to not only understand the microscopic world, but to live within it.

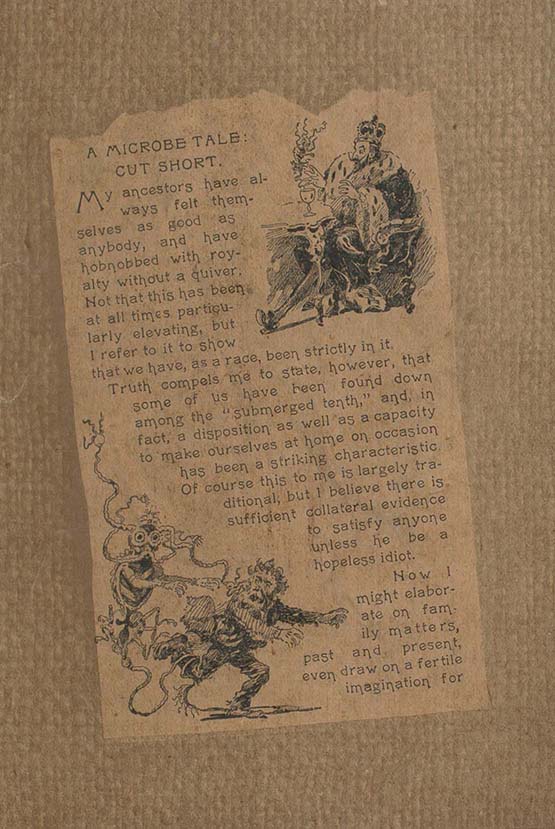

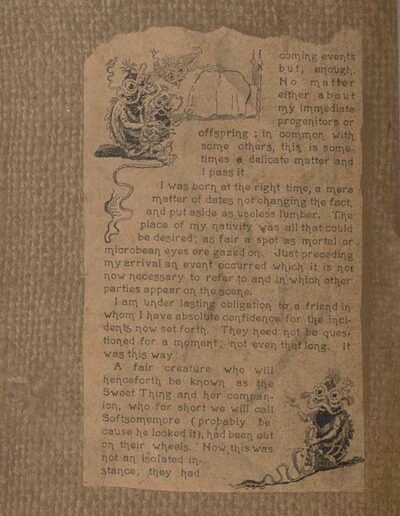

This sampling of pages from Leaves from a Microbe’s Notebook features fanciful depictions of microscopic life forms.