TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

Lilliputiana through a Lens: Secret Portals to Microscopic Worlds

Jakob Dopp

Graphics Division Cataloger

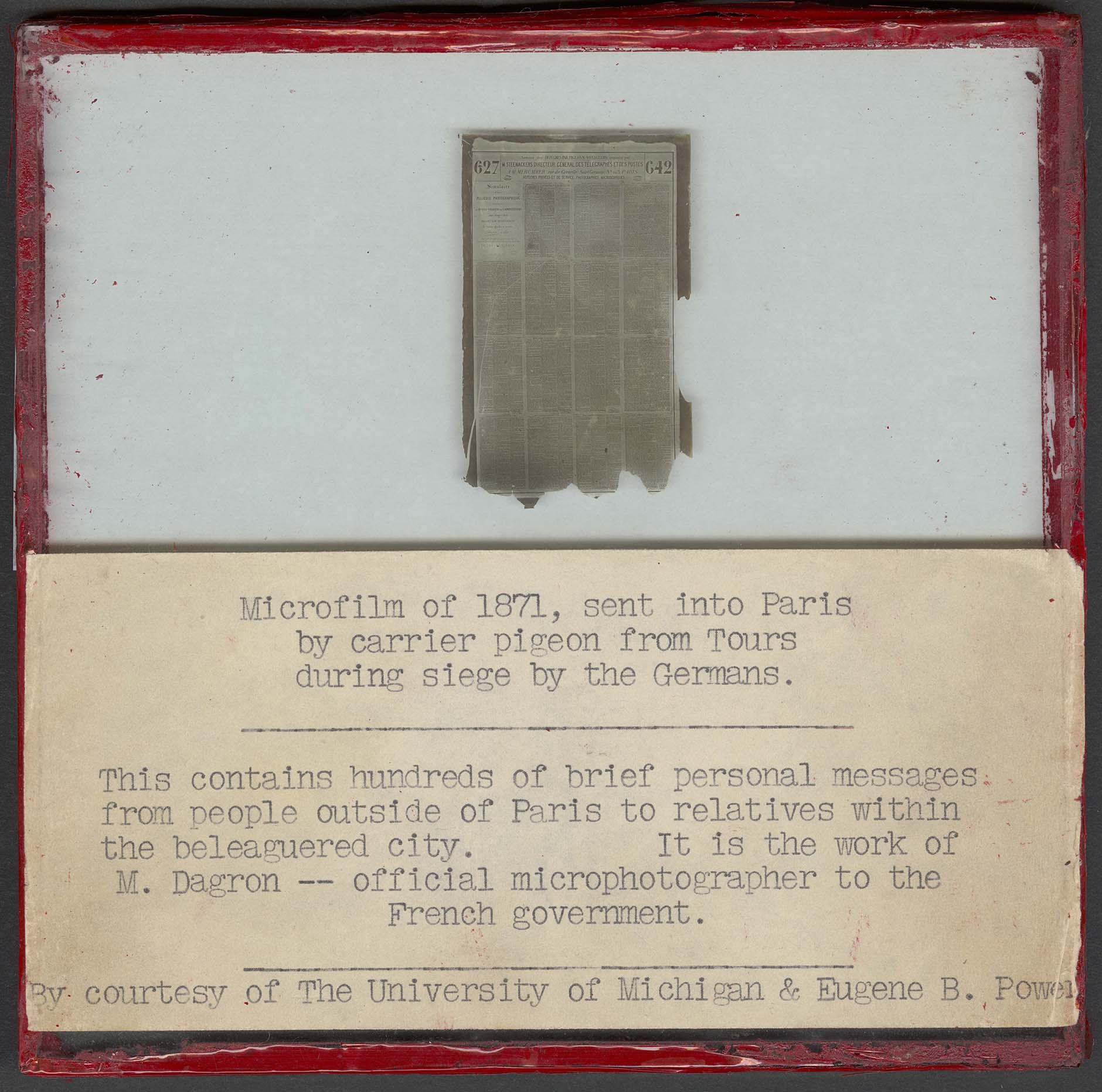

For instance, French photographer René Dagron ( 1819–1900) famously created microphotographs of secret messages and newspapers that were smuggled into Paris by carrier pigeons during the siege of 1870/71 in the Franco-Prussian War. After producing a microphoto, Dagron would carefully extract the exposed film, roll it up, and insert it into a small tube which could be discreetly attached to a pigeon. Upon receipt the microphotos could then be unrolled, placed back upon glass plates, and projected at an enlarged size via magic lantern for viewing. However, long before his involvement in clandestine military communications, Dagron had already established himself as the first person to recognize the lucrative commercial prospects of microphotography.

In 1944 the Clements Library received a set of materials related to Dagron’s Siege of Paris microphotography from University of Michigan alum Eugene B. Power (1905–1993). Power was the founder of University Microfilms International and is considered an important figure in microfilm publishing.

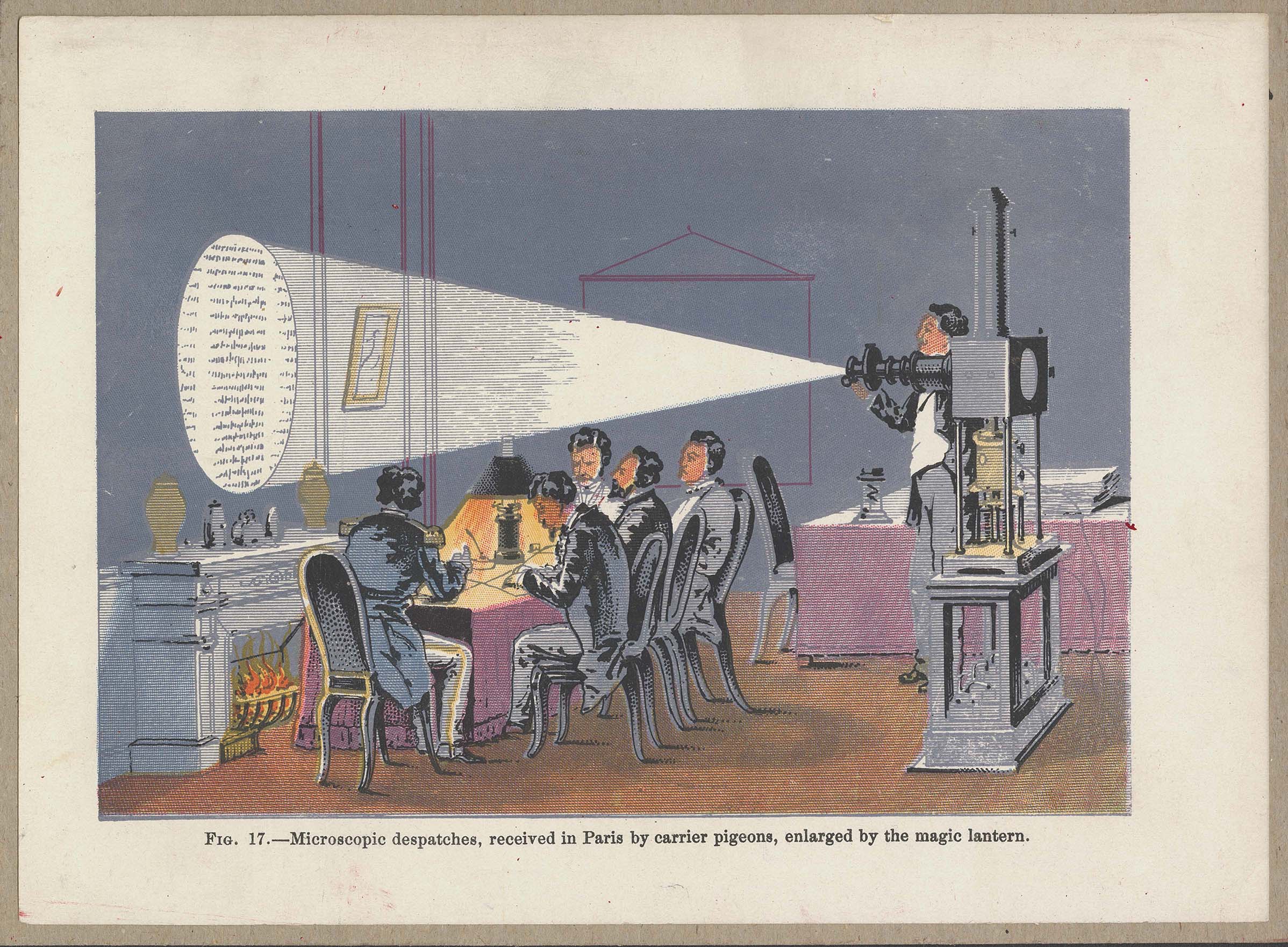

During the Siege of Paris in 1870, the German armies surrounded the city, preventing correspondence with the outer world. Microscopic dispatches flown in by carrier pigeon were viewed by news-starved residents via magic lantern, as depicted in this illustration from John Howard Appleton’s (1844–1930) Chemistry, Developed by Facts and Principles Drawn Chiefly from the Non-Metals (Providence, 1884).

The term “stanhope” stems from Dagron’s ingenious use of an altered lens, a particular type of handheld magnifier created by Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Stanhope (1753–1816). After cutting down one side of a small stanhope lens to make a flat surface onto which a microphoto (often no larger than 2 × 2 mm) could be adhered, the lens could then be implanted inside of tiny holes bored into a vast array of objects including jewelry, pens, rings, scissors, pin cushions, pipes, children’s toys, ornaments, musical instruments, etc. Mass produced trinkets made from carved ivory such as miniature binoculars, telescopes, and eyeglasses were particularly popular objects. Common themes of microphotos found inside of stanhopes include landscape views, street scenes and city/town views, reproductions of famous artwork, major events (such as the World’s Columbian Exposition), and material that can best be described as salacious.

Three of the Clements Library’s stanhope viewers on display, with spools and a measuring tape for scale. The measuring tape itself is a stanhope viewer (from a private collection), note the light colored projection on the top which holds the lens.

The Clements Library has at least four examples of stanhopes that we are aware of (they are sometimes difficult to detect), although hopefully there are others hiding in plain sight that have yet to be found. An ivory letter opener/pen and miniature pair of binoculars containing views of Detroit and Mackinac Island both hail from the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. The Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers contain a miniature ivory telescope with an image of Minnehaha Falls. Last but not least, we have also recently acquired a wooden knife stanhope manufactured as a tourist souvenir which contains views of Mt. Lookout, Tennessee.

The appeal of the stanhope as an entertaining novelty is obvious in that theoretically almost anything can be turned into one. Even the most unassuming everyday object could be bestowed with the magical power of conveying secret imagery. Bearing this in mind, you should always make sure to thoroughly examine any and all antique trinkets you come across as you never know what might happen to contain a secret portal to a microscopic world.

This image captures what is visible to the naked eye when peering through the stanhope lens—in this case the Minnehaha Falls. The microphotograph, itself likely no larger than 2 x 2 mm, may be magnified by a factor of 300 when viewed through the lens.