TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

Morsels of History

Emi Hastings

Curator of Books

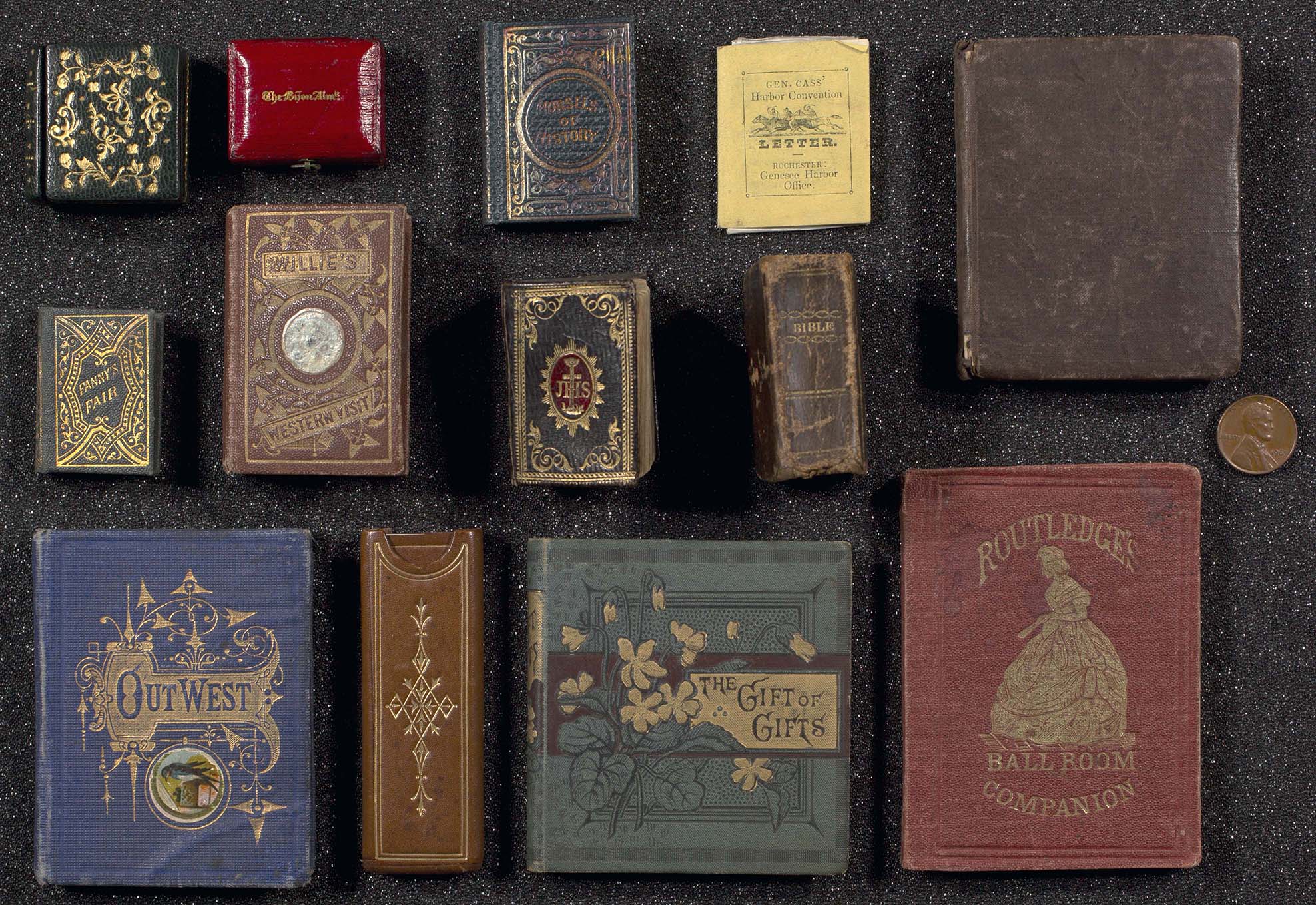

In a quest for the extraordinary, book collectors are often drawn to extremes. This may include the “first,” the rarest, and even the biggest or smallest of books. For the lover of small things, a tiny book has an enduring charm out of proportion to its diminutive size. A miniature book is often defined by collectors as 3 inches (7.6 cm) or under in all dimensions, although the Library of Congress allows miniatures to be up to 3.9 inches (10 cm) in height or width. What draws someone to a miniature version of a text, when a larger version may often be cheaper and easier to read?

Many of the earliest printed miniature books were religious in nature, including such texts as Books of Hours, psalms, and Bibles. For these works, their miniature format served as a religious talisman or a personal reminder of faith, allowing the book to be kept close to one’s body. While the miniature text was still readable, turning the tiny pages required careful attention and focus, a kind of intimacy with the text that called attention to the physical format.

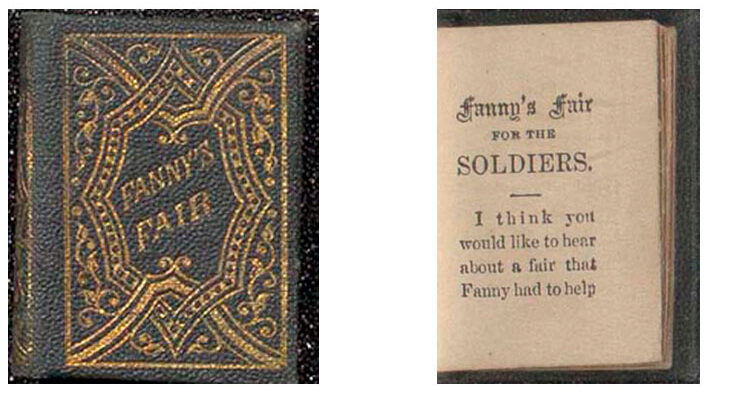

The “Aunt Fanny” of Fanny’s Fair (Buffalo, 1866) was Frances Dana Gage, a feminist and abolitionist who served during the Civil War as superintendent of Parris Island, a refuge for freed slaves in South Carolina.

Miniature Bibles, often called thumb Bibles, began in the 17th century in England and became especially popular in America in the 19th century. They contained a summarized version of the biblical text, sometimes with illustrations. While the first English thumb Bibles may have been intended for adult readers, later American editions were often specifically adapted for children. An edition of Bible History (New York, 1813; 5 cm) states in the preface, “It is hoped, the perusal of this little treatise will so attract the young mind, as to excite a curiosity and love for the scriptures at large.” The possession of a miniature Bible would thus lead the child to further study of the full-sized family Bible.

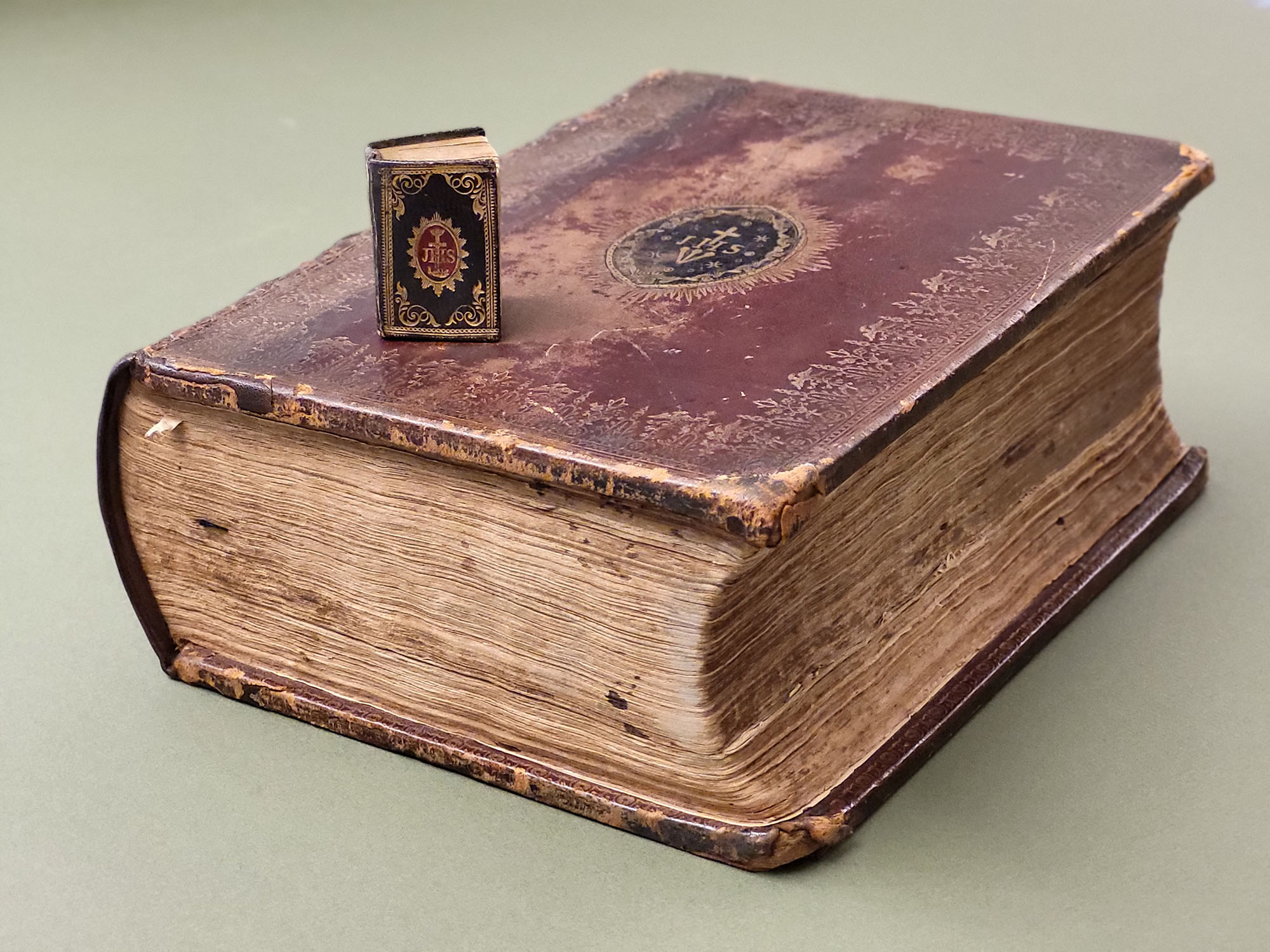

The Bible in Miniature (London, undated) bound in dark leather with decorative stamping in gold. An inscription on the flyleaf read “Mabel Smith from Papa.” Contrasted with a full-sized family Bible in a similar leather binding, The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments (Oxford, 1740) from the Weld-Grimké family papers.

The American Tract Society published numerous miniature books between 1825 and 1899, both for adults and children. Popular devotional works for adult readers included Dew-Drops (Philadelphia, 1884; 5.6 cm), A Threefold Cord (New York, 1953?; 8 cm) and Daily Food for Christians (Boston, between 1882 and 1900; 8 cm), all in multiple editions. The American Sunday-School Union in Philadelphia was also a prolific publisher of miniature books for children, including a popular book of prayers called Small Rain Upon the Tender Herb (Philadelphia, ca. 1835; 3.6 cm)

Schloss’s English Bijou Almanac for 1839 (London, 1838). Red leather slipcase with magnifying glass.

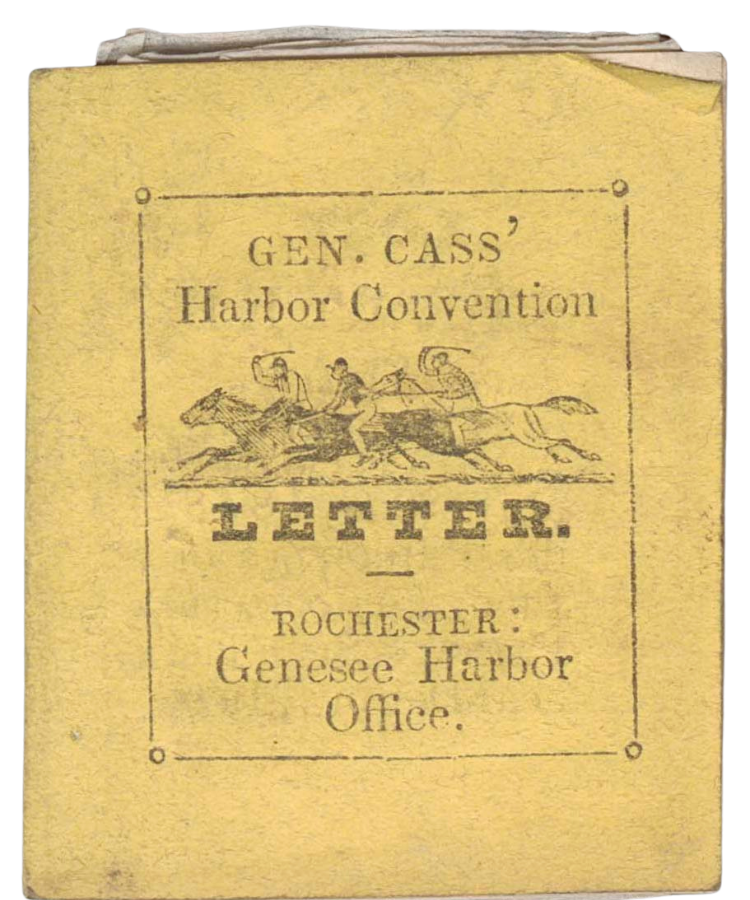

Gen. Cass’ Letter to the Harbor and River Convention (Rochester, 1848). Yellow pictorial printed wrappers, satirical advertisement on rear wrapper.

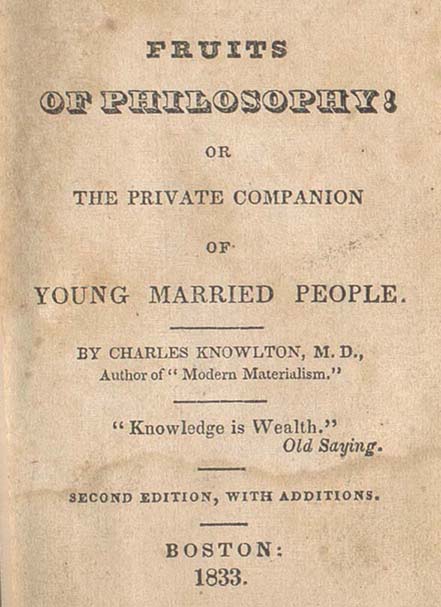

Charles Knowlton, Fruits of Philosophy, or, The Private Companion of Young Married People (Boston, 1833). Bound in plain brown publishers’ cloth.

Beyond their immediate appeal as adorably small objects, miniature books served a variety of purposes, ranging from the frivolous to the sacred. The miniature format made a religious text seem more personal or more appealing to young readers, transformed a plain volume into a tiny work of art, or made information easier to access on the go, whether you needed to look up an unfamiliar word, make a quick calculation, or read a favorite work of literature on the train. The lasting appeal of miniature books speaks to the many different audiences they have served and the ways in which they have been consumed by generations of readers.