TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

On Pins and Needles

Jayne Ptolemy

Associate Curator of Manuscripts

Bah humbug! A quick perusal of daguerreotypes will yield any number of severe-looking portraits that hide any sense of humor the subjects might have possessed.

Above, left: [Older man], by Moses Sutton, daguerreotype. Detroit: [approximately 1851 to 1857]. David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. The majority portion donated by David B. Walters in honor of Harold L. Walters, UM class of 1947 and Marilyn S. Walters, UM class of 1950.

Above, right: [Young woman], daguerreotype. [Kalamazoo, Michigan?]: [approximately 1855 to 1860]. David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. The majority portion donated by David B. Walters in honor of Harold L. Walters, UM class of 1947 and Marilyn S. Walters, UM class of 1950.

The archetypical librarian has their hair severely styled, lips pursed, and a cranky “Shhhhh!” at the ready. But if you’ve spent any time amongst the staff at the Clements Library, you’ll know there’s far more chatter and laughter than shushing going on. Likewise, ask most people what they think of 18th- or 19th-century Americans, and they’ll likely describe some version of a dour, tight-laced party pooper. Black and white photographs often do little to dispel this myth.

The note accompanying the shad, written at a later date, reads, “Sarah Heaton Stiles and Polly Bishop Mansfield had a bet on and Polly was to give Sarah a shad, in payment. And she (Polly) made this shad, perhaps about 1850–2. They were young women.” Polly C. Bishop Mansfield Collection.

Take, for example, these very traditional mid-19th century poems penned by a young Polly Bishop Mansfield on themes of friendship, remembrance, and perseverance. “Through all the changing scenes of life / Of sunshine or of sadness / Amid temptations, dangers, strife / Or in the hours of gladness / I ask one single boon from thee / My friend — wilt thou Remember me [?]”

While there’s a tenderness to the lines, there is admittedly also something rather anonymous about it. It feels like any number of young women might have written them, and you get little sense of Polly Bishop Mansfield as an actual person. If I’m being honest, I likely wouldn’t remember this on its own. It’s only the presence of a small, inside joke that elevates this collection to great heights. The poems, you see, are accompanied by a fish.

This little addendum was pinned into one of Anthony Wayne’s account books. Notice all the other pinholes in the margin, suggesting there were many others like it, in this age before Post-It notes.

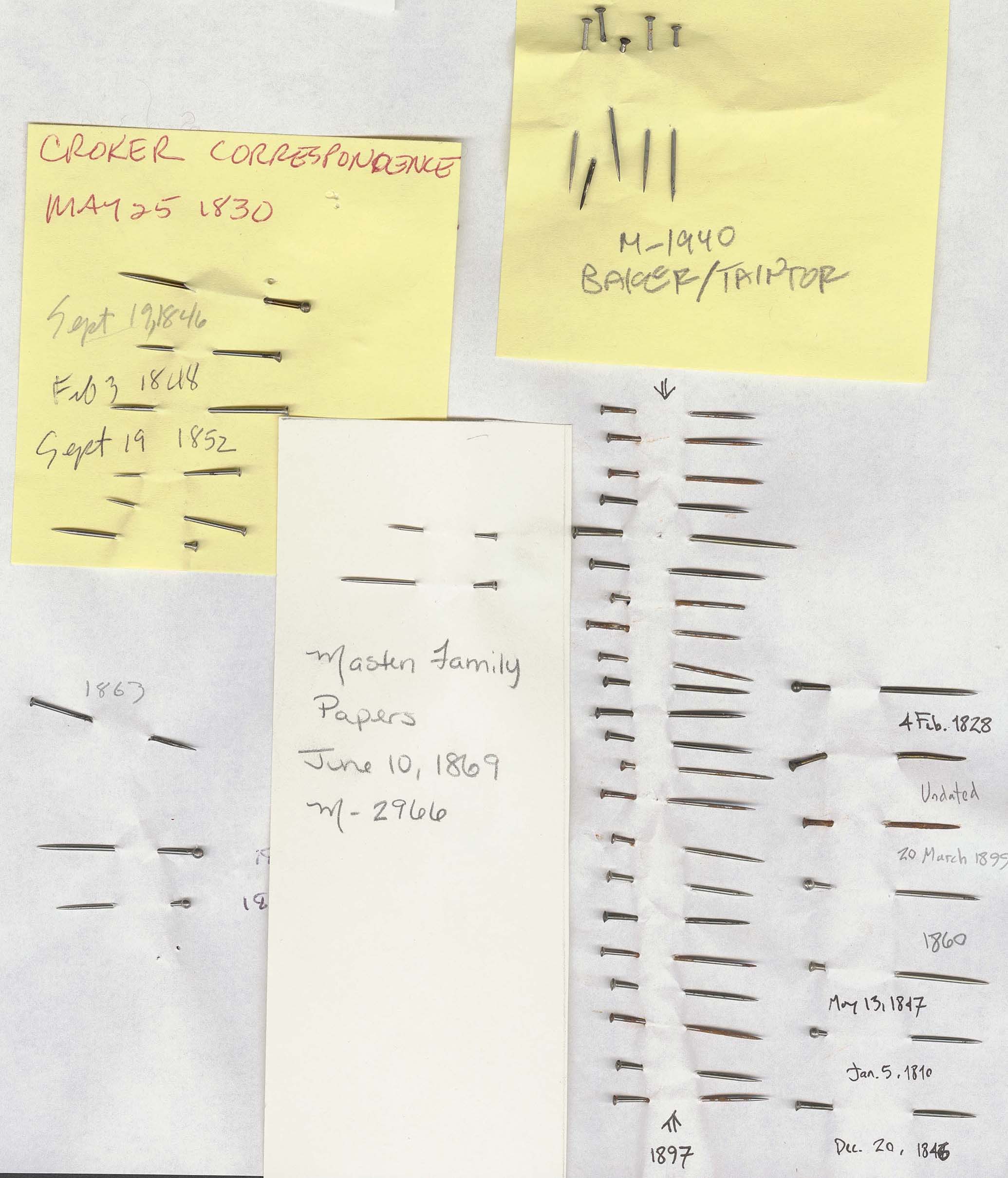

The collection of pins which were removed from documents throughout the Clements Library’s holdings for more than a decade remains uncataloged and still awaits a finding aid.