Digital Research

Digital Research Subject Guide

When you can’t come to the Clements Library’s reading room to access our historical collections, you can still pursue your research using the expanding realm of digital resources. This guide highlights the digital content available at the Clements, related collections and databases hosted elsewhere, and provides some pointers about analyzing and evaluating sources.

Sometimes the best research projects stem from reading through the sources, being sparked by questions, and looking widely for answers. While we face access and travel restrictions during the pandemic, the growing number of online resources grants us the ability to replicate, to some degree, that same process of discovery. Find a rich collection and see where the research questions take you.

More broadly, digital research has many advantages. It can provide wider access to collections, allow you to zoom in to review details on a large document that can be difficult to do in person, and enable you to compare materials held by distant institutions.

Please explore our Digitized Collections page to learn more about the digital resources from the Clements Library’s holdings that are readily available for your use.

Analyzing Digital Images

You will find much variation from institution to institution about how collection content is digitized and presented online. Regardless of the platform, there are some practices that can help you analyze the images and glean the most information from these digital surrogates. Here we pull examples from the three main digital access points at the Clements – our Image Bank, Digitized Archival Collections, and HathiTrust.

Scale

The size of an item can tell researchers a great deal about its function, how it was produced, and how people would have interacted with the object in the past. Looking at an image on a computer screen, it can be difficult to assess the scale of an item. When reviewing a digital image, look for the ruler to determine the actual size of the original. Usually the image on your screen is not a 1:1 scale, but instead it likely has been adjusted to fill the viewer. It can help to have a ruler of your own on hand to help you visualize the dimensions. If the image does not have a ruler shown, look at the description that accompanies the image to see if dimensions are provided.

This tintype photograph of a boy, for example, measures about 4 centimeters. Measuring that out on the palm of your hand can help you understand how small it is. Seeing the back of the item, with the remnants of paper still affixed to it, we get hints that this little image was glued onto a larger piece of paper, perhaps an album, a mat in a frame, or some other device to display it.

Image Bank record for [Studio portrait of male child], tintype, ca. 1850-1890, Thomas Downs Papers.

The need to assess scale also works for large items, as well. At first glance, this map of the St. Lawrence River looks like a thin scrap of paper.

Image Bank record for Thomas Davies, “Draught of the river St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario to Montreal,” manuscript map, 1760, Thomas Gage Papers.

Looking at the dimensions provided in the record, however, you realize it spans some seven and a half feet. What you see on the screen can be misleading. Be sure to check the dimensions of the original to help you grasp the real contours of the item. This can help raise questions about the relationship between the form of the item and its utility. Why is the item this size? What does it tell you about its intended purpose, audience, and how people would have interacted with it? Evaluating whether something would fit in an eighteenth-century pocket or would have been more appropriate to display as a wall-hanging changes how we understand the function of the item itself.

Materiality

When you handle an object directly, you can use all of your senses to help you explore it. You can feel its heft, smell the leather, see wear on the binding, glimpse a watermark on the paper, feel the quality of the materials. This can be harder to determine when working with digital surrogates. A careful reading of catalog records can help you imagine some of these aspects.

The Clements’ copy of the 1493 Latin edition of Christopher Columbus’ letter to the King and Queen of Spain is fully digitized in HathiTrust. Looking at the image on your screen, however, you can’t feel the rich, buttery leather of the binding, a great clue to its high quality.

Digital copy of Christopher Columbus, Epistola Christofori Colom cui [a]etas nostra multu[m] debet: : de Insulis Indi[a]e supra Gangem nuper inuentis (Rome: Stephen Plannck, 1493) as it appears in HathiTrust.

The HathiTrust platform does not include as many details about the volume as can be found in the Clements Library’s catalog record. Read our catalog entry carefully against the images you see to try to get a fuller picture.

The Library Catalog record for the 1493 Columbus volume provides additional information.

In particular, look for the “copy-specific note” – this is where our catalogers provide details about the unique copy of the title that is held at our library. In this record, you’ll read a binding description that gives wonderful detail, highlighting the craftsmanship of the binding as well as some of the repairs that are believed to have been done over the years. Even though you can’t handle the book in person, reading more deeply about the volume’s physical aspects can help you grasp that this book was highly valued by its owners based on the quality of the binding and work put into it as a showpiece.

Zooming in on images can also help you look for clues. What can you see about the texture of the paper? Do you notice any creases, ink smears or blots, tears in the page? A close reading of the object itself, not just its written content, can help you better grasp how it was produced and how heavily it was used.

Compare, for example, two items from our digitized archival collection, the Samson Adams Papers. The first item is a freedom pass for Violet Adams, an African American woman, granting her travel privileges in 1767. The other item is a receipt from 1792 acknowledging Violet Adams received a payment.

Two items from the Samson Adams Papers highlight how focusing on the material clues found in digital content, like staining and wear on the paper, can help you uncover more information about the pieces.

Notice the difference in wear in the two items. The freedom pass is discolored, has small holes along the creases, appears to have gotten damp along one edge, while the receipt, beyond having been folded, appears in very good condition. Violet likely had to carry the pass around with her to prove her right to travel, and the legacy of the document’s use can be read by carefully looking at the paper itself in addition to the text. Take advantage of the high resolution scans, and zoom in closely to look for such clues.

Limitations

No matter how good the digital scan, there are elements of the original that don’t always translate onto the screen. Because equipment often scans directly overhead, lighting is often uniform and flat. Aspects of the original that are apparent in person – the way the light catches on the texture of the paper, how the ink glistens, the hint of a watermark – can be flattened in the digital surrogate. Keep this in mind as you work with the online version.

Take, for example, this manuscript map of the 1758 siege of Louisbourg.

“Plan du port et de la ville de Louisbourg en l’Isle Royale, et des Attaques faites par les Anglois pendant le Siége depuis le 8 juin jusqu’au 26 juillet 1758,” manuscript map, 1758.

Note that the record indicates that the item “contains numerous pinholes,” where mapmakers used pins to tack the outlines of the map onto blank sheets in order to copy the image. Zooming in very closely on the image online, it is difficult to discern where these pinholes are; however, in the reading room, using devices to backlight the map, these holes are readily seen.

Comparing the digital scan of the map and a photo of it being backlit shows how online images do not always capture all of the details.

Relationships

When working in the reading room, the relationship of a single item to its larger collection is often far more obvious than it is when working with a digital surrogate. Working online, a digital image can be interpreted in isolation, but the broader context provides important information for understanding the full meaning of the item. Look at the details provided in the record for the image to see if it indicates whether it is part of a bigger collection.

For example, this image of a Civil War hospital bed gives an interesting look at some soldiers’ experiences as they convalesced. If you click on the “Collection Title” at the bottom of the screen, you’ll be linked to all the other images connected to that collection in the image bank.

Image Bank record for [An unoccupied hospital bed that is covered in netting], Jayne Papers, showing where to find the “Collection Title” to direct you to other materials from the same collection.

Looking at all of the scans in the Image Bank from the Jayne Papers situates them within a broader context.

You can now see that image in conversation with the other images from the collection, broadening your understanding of that one item. To go further, be sure to look for links to the collection finding aid or catalog record.

Look for links to the finding aid or catalog record in order to find more information about the collection or item.

If the image was drawn from a broader collection, the finding aid will provide the most detailed description of the full body of material. If the image is a single item, the link will be to its catalog record, which often includes additional information. Learn about the scope of the collection, relevant background information, and content descriptions to help you assess how the item you’re considering stands in relation to other material in the collection. Evaluate what hasn’t been scanned to determine what you don’t know.

Comparisons

One of the great advantages of digital research is how it enables you to carefully compare items from distant repositories, looking for connections that would be difficult to discern without seeing the two items side by side.

Take, for example, the Clements’ ca. 1850 allegorical map “Ocean of Love” drawn by hand by Albert King.

Albert King, “Ocean of Love,” manuscript map, ca. 1850.

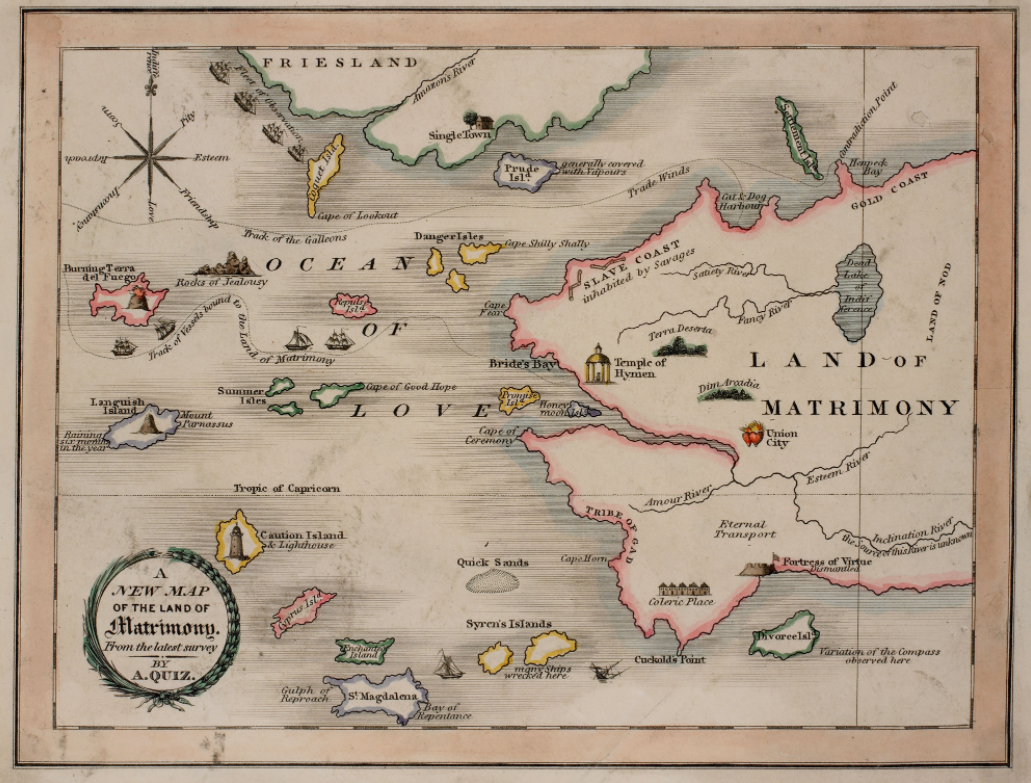

The Clements does not hold any printed maps from this genre. But the British Library does, including one entitled A new map of the land of matrimony, from the latest survey.

A. Quiz [pseudonym], A new map of the land of matrimony, from the latest survey, printed map, ca. 1800s, British Library.

The libraries that hold these two maps are separated by over 3,500 miles, but looking at their digital surrogates side-by-side you can see all the similarities that help you frame Albert King’s manuscript map more robustly. Both feature the Ocean of Love, the Land of Matrimony, the Rocks of Jealousy, the Dead Lake of Indifference. But each includes “locations” that the other lacks. What do these similarities and differences tell us about how each “maps” romantic relationships? Searching across digital platforms can help you seek out and answer such comparative questions.

Online Resources

This list of additional resources for digital research in early American history is not comprehensive, but instead highlights some fruitful avenues for further exploration beyond the Clements Library’s Digitized Collections. The University of Michigan’s United States History Subject Guide provides additional material to explore, including databases relating to Women’s, African American, and Native American History. Many of these require institutional log-ins.

By searching for a library that specializes in your topic, you can then check if they have digitized collections that may be relevant to your interests. For other institutions with strong early American holdings, check out the digital collections at the Newberry Library, the John Carter Brown Library, the Beinecke Library, the American Antiquarian Society, the Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library, and the American Philosophical Society.

Manuscript Materials

- American History, 1493-1945 features material from the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History’s “outstanding collections on American history. It is full of spectacular individual items, but it also has rich veins of manuscript research material.”

- Library of Congress Digital Collections includes a variety of sources, ranging from printed items to manuscript collections. Their manuscript division also has a page featuring their digitized collections.

- Colonial America covers “the period 1606 to 1822. CO 5 constitutes the original correspondence between the British government and the governments of the American colonies. In particular, the collection includes correspondence of the colonial governments with the Board of Trade, the Secretary of State for the Southern Department and the Secretary of State for the Colonies, together holding responsibility for the British possessions in mainland North America and the Caribbean.”

- Colonial State Papers “provides users with access to primary source documents from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. The earliest English settlements in North America, encounters with Native Americans, piracy in the Atlantic and Caribbean, the trade in slaves and English conflicts with the Spanish and French are all covered in this database. Combines two resources: CO 1: Privy Council and related bodies: America and West Indies, Colonial Papers and The Calendar of State Papers, Colonial: North America and the West Indies 1574-1739.”

- New York Public Library’s Early American Manuscripts Project features “high quality facsimiles of key documents from America’s Founding, including the papers of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Drawing on the full breadth of the Library’s manuscript collections, it also makes widely available less well-known manuscript sources, including business papers of Atlantic merchants, diaries of people ranging from elite New York women to Christian Indian preachers, and organizational records of voluntary associations and philanthropic organizations.”

- Colonial North America at Harvard Library “provides access to remarkable and wide-ranging materials digitized as part of an ongoing, multi-year project. When complete, the project will make available to the world approximately 650,000 digitized pages of all known archival and manuscript materials in the Harvard Library that relate to 17th- and 18th-century North America.” It is also worth exploring Harvard Library‘s broader catalog. By selecting “Limit Digital Materials” in the Limit field, you can filter your results to show only materials with digital surrogates.

- The Native Northeast Portal “represents a scholarly critical edition of New England Native American primary source materials gathered presently from the partner institutions into one robust virtual collection, where the items are digitized, transcribed, annotated, and edited to the highest academic standards and then made freely available over the Internet, using open-source software.”

- The Papers of the War Department 1784-1800 includes “42,000 documents of the early War Department many long thought irretrievable but now reconstructed through a painstaking, multi-year research effort available online to scholars, students, and the general public. The Papers record far more than the era’s military history. Between 1784 and 1800, the War Department was responsible for Indian affairs, veteran affairs, naval affairs (until 1798), as well as militia and army matters.”

- The Global Commodities: Trade, Exploration, and Cultural Exchange database is a “collection of digitized primary source material to facilitate the study of global commodities in world history… Materials are drawn from several libraries, including the American Antiquarian Society, the Bristol Record Office, the British Library, Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, the Library Company of Philadelphia, New York Public Library, the Newberry Library, and the National Archives at Kew, among others.”

Printed Materials

- HathiTrust Digital Library is “a partnership of academic and research institutions, offering a collection of millions of titles digitized from libraries around the world.” You will find hundreds of titles from the Clements Library here, and under the Emergency Temporary Access Service they are providing full text of many other publications if you use your institutional login.

- Internet Archive is “a non-profit library of millions of free books, movies, software, music, websites, and more.”

- Google Books includes fully scanned volumes. Sometimes just Googling the title of a book you want to access can help you identify sites with digital copies. Use quotation marks around text that you want Google to search for exactly.

- Early American Imprints, Series I: Evans, 1639-1800 “contains a range of publications, including advertisements, almanacs, bibles, broadsides, catalogs, charters and by-laws, contracts, cookbooks, elegies, eulogies, laws, maps, narratives, novels, operas, pamphlets, plays, poems, primers, sermons, songs, speeches, textbooks, tracts, travelogues, treaties and more.”

- Early American Imprints, Series II: Shaw-Shoemaker, 1801-1819 “provides full-text access to American books, pamphlets and broadsides published in the first nineteen years of the nineteenth century, covering every aspect of American life during the early decades of the United States. In addition to books, broadsides and pamphlets, the collection includes published reports and the works of many European authors reprinted for the American public. Additionally, a large number of state papers and early government materials—including presidential letters and congressional, state and territorial resolutions—chronicle the political and geographic growth of the developing American nation.”

- Early American Newspapers (America’s Historical Newspapers) “allows users to search more than 1,000 U.S. historical newspapers published between 1690 and 1922, including titles from all 50 states.”

- Fulton Search is a freely accessible “alternative search interface for over 47,059,000 historical newspaper pages.”

- The Library of Congress’s Chronicling America allows users to “search America’s historic newspaper pages from 1789-1963 or use the U.S. Newspaper Directory to find information about American newspapers published between 1690-present.”

- American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collection, 1684-1912 includes “full text of thousands of American periodicals collected by the American Antiquarian Society (AAS), documenting the life of America’s people from the Colonial Era through the Civil War and Reconstruction… also available in 50 targeted topic subsets (which can be selected, after entering the database, by clicking on “Choose Databases”).”

Maps

- The David Rumsey Map Collection is extensive. Its historical map collection has “over 100,000 maps and related images online. The collection includes rare 16th through 21st century maps of America, North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, Pacific, Arctic, Antarctic, and the World.”

- The online inventory for Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique Maps includes some 10,000 “antique maps, sea charts, and atlases from all parts of the world,” spanning from the 15th to 20th centuries.

- The Library of Congress’s Geography & Map Reading Room has an Online Collections guide that highlights a number of different areas to explore.

- The Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library is “ranked among the top ten in the United States for the size of its collection, the significance of its historic (pre-1900) material, and its advanced digitization program.”

- George III’s Collection of Military Maps “comprises some 3,000 maps, views and prints ranging from the armies of Charles V at Vienna in 1532 to the Battle of Waterloo (1815).”

Visual Materials

- The Library of Congress – Prints and Photographs Division features a massive collection of visual images representing America from the 15th century to the present.

- The John Carter Brown Library hosts a digital platform with notable collections of engravings, maps, book illustrations, political cartoons and more related to the early history of the Americas.

- The Huntington Library Digital Library includes approximately 250,000 images representing world history and culture.

- New York Public Library Digital Collections has close to 900,000 images. Browsing by division can help you narrow your browsing to visual collections.

- The George Eastman Museum “encompasses works made in all major photographic processes, from daguerreotype to digital, includes work by more than eight thousand photographers, and continues to expand.” 250,000 images related to photography and photographic and cinematographic technology can be found in their online collections.

- Colonial Virginia Portraits is “an interactive database of oil portraits with a documented history in Virginia or featuring colonial Virginia subjects painted before ca. 1776.”

Last Updated 8/22/2020