Centennial (DRAFT)

First announced in February 1920, the library building was a gift from Regent William L. Clements of Bay City to the University of Michigan. Clements also donated his extensive collection of Americana, valued at the time at close to $450,000, and consisting of 20,000 volumes of rare books, 2,000 volumes of early newspapers, several hundred maps, and the papers of Lord Shelburne, the British Prime Minister who negotiated the peace ending the Revolutionary War.

Construction of the library building began in 1922, requiring the demolition of an aging engineering building to accommodate the $200,000 structure, which was designed by Albert Kahn in Italian Renaissance style. Late in his life, Kahn declared that the Clements was the building for which he would most like to be remembered. Kahn originally planned a series of shields over the entrance, but William Clements insisted on only having 3: one shield of the United States, one of Michigan, and one of the Washington family. However, the shield was not George Washington’s because it had thistles, and Washington was not a Scot. Kahn had found the shield in a book of heraldry and marked it, but somewhere along the way a page was turned and the wrong shield was used.

The dedication of the Clements Library took place on Friday, June 15. Dr. J. F. Jameson, director of historical research at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, D.C., was the principal speaker. His topic was “The American Historian’s Raw Material.” Acceptance of the gift to the University was made by Regent Victor Gore of Benton Harbor on behalf of the board of regents. President Marion L. Burton declared it “the greatest day in the history of a great institution.” Jameson similarly called the donation “in some aspects the greatest gift ever given any university.”

A Michigan Daily article describing the papers of William Petty, 1st Marquis of Lansdown, 2nd Earl of Shelburne commented “Although the Clements Library will be available for study to graduate students only whose interest is mainly centered on historical research, the undergraduates are by no means excluded from its precincts. On the contrary, they are urged to inspect it.” However, in a later editorial piece in the same publication, Adams pushed back against criticisms of the library’s strict policies that only seasoned scholars had access to the rare books. He wrote: “The statement that the ‘student can’t quite get at the books’ is quite right—but it shows that there is a fundamental misconception of the purposes of the Library. Whoever makes that statement assumes that the books are intended for the ’students.’ Moreover, whoever makes that statement fails to understand that in the modern, overgrown university there are some of us who make a sharp distinction between ‘students’ and ‘scholars.’ This library is intended for the use of the scholars of the University of Michigan, be they faculty or undergraduates or graduate, but no one is likely to say that all the ‘students’ are ‘scholars.’ In fact, I am inclined to think, and this is only a personal opinion, that the great majority of the students are not scholars. The conclusion of their relationship to the library is inevitable.” Adams goes on to recall explaining to Clements when he was appointed director that he envisioned the role as one of “mediating between being careful and hospitable.” The editorial has since become notorious in debates about accessibility and archives.

R.I. Lovell, a graduate of the University of London, became the first British scholar to conduct research at the Clements Library when he was brought on a scholarship established by Frances E. Riggs to support the study of American history. Lovell remarked: “Tis a jolly fine university you have here…I couldn’t have come to a better place. The Clements Library of Americana is simply marvelous and offers everything one could want in the way of facilities for research in American history.”

Theodosia Burton, the daughter of University of Michigan President Marion Burton and his wife Nina, married George Stewart at the Clements Library in May 1924. Stewart was an instructor in English at the university. After the ceremony, a reception was held in the President’s house next door. ‘Ted’ Burton later recalled, “I don’t think anyone else has ever been married at the Clements Library.”

In February 1925 the Clements hosted an exhibition dedicated to the economic history of the colonial period. Featured were the newly acquired Strachey papers through a descendant of Sir Henry Strachey, who was secretary of the commission for restoring peace with America in 1774.

Colonel Lawrence Martin, Chief of the Maps Division at the Library of Congress, inspected the maps at the Clements Library on his way to Wisconsin to resolve a dispute about the state line between the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Wisconsin. Martin had a strong reputation as an expert witness in boundary disputes, having served as a consultant in Europe after World War I (including the Austria-Hungary boundary) and in several state disputes in the U.S.

The Wisconsin-Michigan boundary lawsuit, brought before the Supreme Court, concerned the determination of unsurveyed sections of the boundary between northern Wisconsin and the western end of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, in and along the Brule and Menominee Rivers, especially in determining the division of islands and rapids, the latter a source of hydroelectric power. It also considered the state boundary that might affect fishing rights in Green Bay, the part of Lake Michigan, between the Door County peninsula of Wisconsin and the Michigan mainland. The suit was settled by the Supreme Court in 1926 with a newly determined, verbally described boundary.

The Clements Library hosted an exhibition of Mississippi Valley maps arranged for the Mississippi Valley Historical Association (the precursor to the American Historical Association). Following their annual meeting, the maps were exhibited to the public. Among the maps shown were a series of photographic reproductions of the manuscript maps of Joliet, Franquelin, and others located in the Archives de la Marine at Paris. Under Mr. Clements’ instructions, 135 of the most important of these were photographed by a French historian, Abel Doysié, who had become familiar with materials related to American history located in French archives during his long employment by the Carnegie Institution. These photostatic reproductions represented the only copies available outside Paris.

Clements employed Doysié directly to photograph maps using the new technology of the photostatic machine, a camera which could reproduce documents and plans at a 1:1 scale. Although the process could not reproduce the colors of the original, it allowed a reader or researcher access to the content of the original document, at its original scale.

The Clements Library held an exhibition related to Spain’s conquest of Mexico, focused on the career of Hernando Cortez. Cortez was the governor of New Spain following his conquest of the Aztec Empire in 1521. The exhibit included this map of Tenochtitlan from 1524.

The Clements Library hosted an exhibition of materials related to Francisco Pizarro’s invasion of the Inca Empire and the establishment of a Spanish colony in Peru in connection with Professor A. S. Alton’s class on the history of Hispanic America. This was likely the first Clements Library exhibit created in conjunction with a specific U-M class.

In December 1925, William Clements announced that he had acquired the papers of General Nathanael Greene and Sir Henry Clinton. The Greene Papers included 500 letters from Greene to George Washington and 50 from Washington to Greene. The Henry Clinton Papers and Nathanael Greene Papers would eventually become part of the Clements Library collections on the settlement of Clements’ estate in 1937.

The library held an exhibit focused on Benjamin Franklin featuring materials on loan from the library of the businessman and Americana collector William Smith Mason. The exhibit included materials related to Franklin’s work in the printing trades, scientific research, and correspondence with John Paul Jones, George Washington, and Thomas Jefferson.

The first 100 documents from the Henry Clinton Papers to be loaned to the Clements Library for display in May 1926. Clements had insisted on having them all properly bound and processed before displaying them, especially considering that this batch contained the Washington letters. The Clinton papers were exhibited using the wall cases in the reading room as display cases. Among the materials were manuscript maps and some contemporary printed maps, such as Bernard Romans’ Map of Florida from 1774. Until these materials became part of the library’s collection in 1937, the only researchers to consult them did so at Mr. Clements’ home in Bay City, at his invitation.

The Clements Library figured prominently in tours of the University of Michigan campus that were offered during summer sessions. The purpose of the summer tours was to aid those in Ann Arbor in becoming better acquainted with the university. The tour of the Clements included taking visitors through the stacks, order room, and cataloging department, with all the various library methods of library work being explained to visitors along the way. Visitors were also able to view some items from the collection related to early American history.

The Clements was visited by guests from 15 foreign countries from the American Library Association, who were given a tour of the library by its staff. Particular interest was expressed by the delegates in the profusion of labor saving devices in use at the Library. The teleautograph and the book conveyers came in for special commendation.

The Clements Library hosted an exhibit of materials related to Early American printing, including the “Doctrina Breve … copuestra par el Reveredissimo S. do fray Jua Cumarraga,” printed in Mexico in 1544. Considered the earliest surviving complete book printed in the Americas, it was a catechism printed in Mexico City for the first archbishop of Mexico, Juan de Zumárraga. One of the first books printed in South America, Tercero Cathecismo y exposicion de la Doctrina Christina (Lima, 1585)—a catechism printed for missionary use in Spanish and Quechua—was also featured at the exhibit.

The Clements featured in a campus film shown to 500 alumni. Originally planned as a means of bringing alumni in closer contact with the University, the film was later scheduled to be shown at alumni gatherings throughout the country. It was filmed under the direction of the Metropolitan Moving Picture company of Detroit and general manager A.B. Jewett. Shooting was paid for by the university. A Michigan Daily article noted: “especially effective among the pictures taken are those of the Clements library and of the football games played last fall. A number of rare volumes possessed by the library are shown in the scenes taken there.” The film adopted a loose narrative structure of a returning alumnus and his son and daughter who greeted him and showed him around the campus.

William Clements purchased the papers of General Thomas Gage (British Commanding General for North America from 1763-1775) in January 1930, and director Randolph Adams went to collect them in March. Mr. Clements concluded his negotiations with Lord Gage quite swiftly. After the sale was completed, Gage remarked that he was “impressed by the promptness” of the library. The papers were brought to Mr. Clements’ house in Bay City; like the Clinton and Greene Papers, they would not become part of the Clements Library collections until 1937, when they would become one of the largest and most important collections related to the Revolutionary War at the library. The Deputy-Keeper opined that William Clements now owned the “greatest and most important manuscript collection that has ever left that has ever left England at one time.” Lord Gage requested that he be allowed to keep one map of New York dedicated to General Gage, a wish that was granted by Adams on Clements’ behalf.

William Clements acquired a series of letters, diaries, and other documents created by Hessian officers hired by the British during the Revolutionary War, a collection that was discovered after having been locked in a trunk in Castle Hueffe in German Westphalia for nearly 150 years. These manuscripts had never been available to historians until they became part of the library’s collection in 1937, and director Randolph Adams remarked that they would shed invaluable new light on the Revolutionary period. The collection included 432 letters from Baron Wilhelm von Knyphausen, commander of the mercenary troops, addressed to Baron Friedrich von Jungkenn, minister of war of Hesse-Cassel.

Ann Arbor was the meeting place for the National Academy of Science for the first time, which included a tea hosted at the Clements. William Clements and wife Florence, Randolph Adams and wife Helen, and Frederick Novy and wife Grace received the guests, among which was physicist Karl T. Compton of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who presented a paper on the behavior of a cathode in an ionized gas.

After unsuccessfully running for re-election to the University of Michigan Board of Regents in February 1933, William Clements in December announced his retirement for the following year. He had served the university for 24 years as a member of the Board of Regents.

In November, the Clements held an exhibit on the practice and history of forgery. The library displayed famous forgeries of historical documents, including the Columbus letter, the letters of Washington, Cotton Mather’s Map of New England, and the famed Vicksburg Citizen wallpaper edition. The exhibit was so popular it was extended beyond the football season.

On November 6, 1934, William Clements died in Bay City at 73 years of age of a heart attack. Following his death, Clements’ personal collection of maps, manuscripts, prints, and books in Bay City was designated to be donated to the Clements Library. However, when the will was submitted to probate in Bay County, it specified that the University could receive the materials only if it paid $400,000 to the Clements family estate. Some of these materials were already in the university’s possession at the library. Charles F. Hemans, member of the Board of Regents, was outraged, and pointed out that at least one part of the collection, the Oxford Letters on Early Americana, were actually purchased with money given to Clements by the university for that purpose.

On November 29, 1934, the Detroit Trust Co. announced that the remaining collection of historical materials in the possession of the late William Clements, worth $400,000, was donated to the university. Clements’ home and its contents were left to his children, and his son-in-law, Harry S. Finkenstaedt, along with the Detroit Trust Co., were requested to be appointed as executors. A Detroit Free Press article suggested that Clements had left the valuable materials to his family because his fortune had all but vanished by the time he died. In his later years, he contributed $800,000 to a bank reorganization plan in Bay City out of a ‘moral obligation’ to protect depositors from loss, but the university claimed the materials Clements was asking $400,000 for already belonged to them, as outlined in a contract he signed 12 years before his death.

Months after the Clements will dispute was settled, William Clements’ daughter Elizabeth publicly denied that he had obligated himself to leave everything to the university. She also denied the existence of the Oxford Letters collection that Charles Hemans claimed was purchased by Clements with university money. President of the university Alexander Ruthven also said he knew of no such collection. Clements’ daughter pointed out the effect of the Depression on her father’s modest fortune, and that “justice to his family prevented his giving these manuscript collections outright to the University.”

The Clements was gifted a rare shorthand account of Abraham Lincoln’s final moments. Mrs Nellie Strawheuker donated the account of Corp. James Tanner, a clerk in the War Dept at the time, who was with the former President when he died. The letter is addressed to Henry F. Walch and describes Tanner’s having “the priviledge of standing by the death bed of the most remarkable man of modern times, and one who will live in the annals of his Country as long as she pro continues to have a history.”

A significant George Washington letter was discovered in the Thomas Gage papers. John Alden, a PhD student in the U-M history department, found a previously unpublished and unknown letter written in Washington’s hand dated May 17, 1768, addressed to John Blair, president of the council of Virginia. In the letter, Washington lobbies for the Virginia traders over a proposed Native American boundary line which would have compromised their trading routes.

The Adult Education Institute exhibited a series of educational films, including a sound strip based on original documents at the Clements. Director of the Extension Service, Dr. Charles A. Fisher, said of the film: “Much of the valuable material, including original documents, art objects and rare books which up to now have been of use only to those who could come to the university, can through the medium of visual education be made available to the people of the state and country.”

A sound film depicting the betrayal of Benedict Arnold was shown to the Men’s Education Club at the Michigan Union. The film was made by Professor Wesley H. Maurer, who based it on original manuscripts at the Clements in collaboration with Eugene Powers of the University Microfilms and Clements director Randolph Adams.

The University of Michigan made plans in 1940 to obtain microfilms of all 18th century American magazines that were previously absent from the university libraries. Microfilms are photographic reproductions of printed material stored in small rolls of film for use in a projector. The objective was to develop a complete record of all magazine literature printed in the United States before 1801 and for it to be stored at the Clements.

The second ever Microfilm camera was developed in Ann Arbor by Eugene Power, founder of University Microfilms, Inc. in 1938. He later brought the camera to the British Museum in London, where it was commissioned to to microfilm manuscripts in British libraries that were considered vulnerable to German bombings in World War II. Power spent ample time at the Clements as an undergraduate at the University of Michigan, and was first introduced to Early Americana as a student by Randolph Adams.

The library’s historic copy of the Declaration of Independence from the Lord George Germain papers was lent to the Library of Congress as part of the celebration of the bicentennial of Thomas Jefferson’s birth. This copy featured the original signatures and is generally considered the true original, however, another copy that the Clements still holds was contended by Randolph Adams to be the ‘true’ original, because it was the one that was sent to the British to notify the colonial secretary. It was only signed by John Hancock.

Howard H. Peckham, curator of manuscripts in the Clements Library, was appointed University war historian, and charged both with compiling the story of the University’s war activities and with issuing public reports on the subject from time to time. The University, according to the President’s Report for 1943-44, was “determined to avoid the mistake which was made in the World War and to keep currently an account of its own part in the present conflict.” The collection of historical materials was naturally an important phase of this work, and the Michigan Historical Collections was designated as the repository for them. Many of the alumni in the armed services were asked to contribute written or printed materials to the University’s war collections. The post was supported by the Michigan Historical Society.

During the war, the library received invasion notices: “William Clements library at the University of Michigan has just received a set of notices prepared for civilians of France for the invasion. Sent by a former student, they include General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s proclamation that ‘the hour of deliverance had arrived.’ Others order complete blackout, curfew, and surrender of arms, war materials and radio transmitters.”

In January 1945, Howard Peckham resigned from the Clements and went to Indianapolis as director of the Indiana Historical Bureau. F. Clever Bald took over as war historian.

As war historian, F. Clever Bald curated a series of exhibitions related to the war materials the Clements had been collecting. Randolph Adams was very alert in securing materials from men in service, and spoke to classes and convocations of training groups on campus to urge them to send what they found overseas back to the university. Most notable among these was a Nazi flag a soldier had seized on the campus of the University of Cologne. The large banner was put on display in the basement of the Clements Library along with other materials relating to World War II. These included Japanese, German, and Allied books and pamphlets and propaganda materials sent by alumni. Bald spoke in Lane Hall at a Veterans’ Organization meeting and showed an exhibit of enemy propaganda against Allied troops. The exhibit included Nazi banners and pamphlets.

As part of its wartime collecting, the Clements acquired one of the initial 110 copies of the Charter of the United Nations (published June 1945). The copy was received inscribed by Alumnus-Senator-Delegate Arthur H. Vandenberg. The Clements also decided to keep No. 28 of The Missourian (Sep 1945) produced by the printing press of that ship in Tokyo Bay.The copy came with a letter from Printer’s Mate Louis A. Gainsley, who described the press in detail. Gainsley was originally from Ann Arbor, and worked at a gas station two blocks from the Clements. Finally, radioman Second Class George R. Tweed, who “hid out in the hills of Guam throughout the Japanese occupation,” reported that he had a copy of Modern Algebra (1933) with him. He sent it back to Professor Schorling who then presented it to Clements because it “saved him from mental degeneration during those years.”

The library purchased a model of the sidewheel steamboat “Walk-in-the-Water,” famous in the annals of Great Lakes history as the first steamboat to ply Lakes Erie, Huron, and Michigan. Following its launch in 1818, the “Walk-in-the-Water” sailed the lakes for three years before being wrecked in a gale near Buffalo in 1821. The model is still on display in the library’s Avenir Reading Room. Assistant curator of books, Georgia Haugh, was pictured admiring the model steamboat in the Michigan Daily.

The papers of Lewis Cass—advocate of U.S. expansion into Indian country, Governor of Michigan Territory from 1813 to 1831, U.S. Senator, Secretary of War and Secretary of State—came to the Clements Library in 1950. The papers had thought for 80 years to have been lost. Once a gift to the university from Lewis Cass Ledyard III (great-great grandson of Gen. Cass), the documents were used by Frank B. Woodford when writing his biography of Cass. The papers were found in a barn on Ledyard’s Long Island estate.

The library boasted its improved policy of accessibility and commitment to education and outreach in 1952. Looking back on its developments, the library stated: “Except in these annual reports, the Clements Library has not publicized its desire to make the Library available to groups of students and visitors interested in learning about the collections. Yet over the years, we have acquired a following of teachers and friends who request use of the Library for meetings and lectures. Our work with junior high-school and high-school students started several years ago with visits from Ann Arbor students who had completed their study of the American Revolutionary War. We invited those students here to learn something about the Library and to see original materials penned by the men and women about whom they had been studying. Nine groups from local schools, numbering about 240 students, came here last season. Gradually news of the availability of the Library for such teaching purposes has spread outside Ann Arbor. We now receive visits from students in Garden City, Ypsilanti, Brighton, Plymouth, Flint, Toledo, Hillsdale, Wayne, Grass Lake, and elsewhere.”

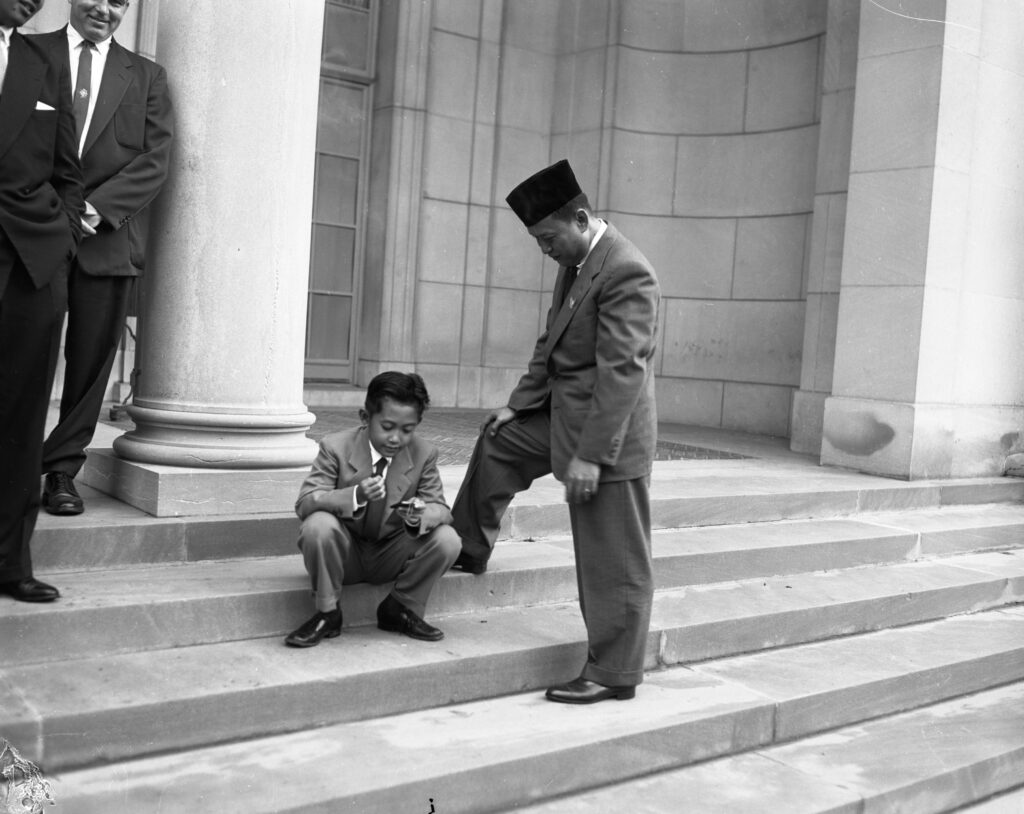

The prime minister of Thailand, P. Pibulsonggram, visited the University and was granted an honorary degree in a ceremony held in the Clements Library.

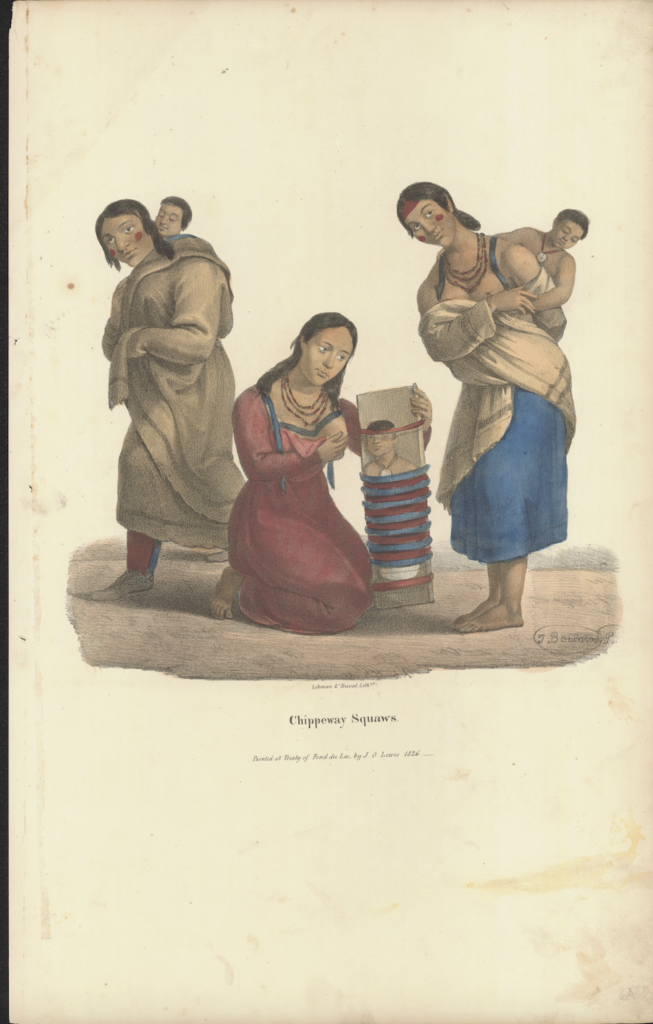

As part of the Michigan Indian Midsummer Festival, the Clements displayed an exhibition relating to the Indians of the Western Great Lakes, featuring crafts in birchbark, split ash and porcupine quill, as well as prints of Chippewa Indian Treaty Councils by J. O. Lewis in the 19th century.

The library featured in an educational film made by the University of Michigan for adults. The second half of the hour-long program was about early American history, and was dramatized and based on manuscript materials from the Clements. Director Howard Peckham narrated the series.

The Clements hosted the conference of the International Council for Philosophy and Humanistic Studies, sponsored by UNESCO. The library was closed while the Council was in session. A special address was given by the Honorable Robert H. Thayer, special assistant to the Secretary of State for the Coordination of International Educational and Cultural Relations.

In the summer of 1960, the Clements Library announced its inaugural Lilly Endowment Fellowships. Three scholars were selected for grants, which were intended to support research in the Clements collections that would lead to eventual publication. These were the first visiting research fellowships at the Clements Library, and some of the earliest such fellowships anywhere specifically for early American research.

Prince Souvanna Phouma, neutralist premier of Laos, gives speech sponsored by the South and Southeast Asia Center in the Clements. In what was his first speech in an American university, Prince Souvanna attacked communism and called for neutralism. The Laotian government were fighting the communist-dominated Pathet Lao rebellion at the time. Souvanna expressed gratitude to the US for helping “resist the insidious tide which is unfurling over that part of Asia and threatens to engulf all of us.”

The preceding week had witnessed a strike against classes by the Black Action Movement, which also won support from some white students. On March 26 about two hundred occupied the Library. They were confined to the Main Room, where they held a meeting for half an hour. After their exit minor damage to decorative items was found.

By March 30 the strike was still on, and so the library had to decide whether to proceed or not with the annual Founder’s Day program. They feared that sight of guests entering the building would induce students to follow in and interrupt proceedings. Therefore for the first time since its inception in 1935, Founder’s Day on April 1 was cancelled.

Associates were invited to the usual Founder’s Day observance on April 1, when Professor LaMont Okey’s graduate students in interpretive reading gave lively excerpts from the Library’s etiquette books. The title of the program was “Gentle Manners and the Art of Politeness.” Okey made the selections and directed the presentation. The books cited formed part of a continuing exhibition, “American Sheet Music Illustration.”

In April, the Clements put on a program on nineteenth-century American ballroom dancing. Pauline Norton coordinted the efforts of the orchestra from the University of Michigan and the dancers from Eastern Michigan University. Three performances were held, a grand performance for the Associates, one for the Sonneck Society, and one for the general public.

An exhibition titled “Spiritual Song: The Meaning of African American Freedom in the Nineteenth Century” was held at the Clements, which represented the personal and public lives of free African Americans during the slavery era. It was put together by Rob Cox, the collection’s curator.

An exhibition focusing on the history of cookbooks and cookery opened at the Clements in the Summer of 1996. Jan Longone, owner of the Wine and Food Library in Ann Arbor, marked the 200th anniversary of the first American cookbook by Amelia Simmons (published 1796) with the display. It was titled “American Cookery: The Bicentennial 1796-1996.”