The War of 1812: A Bicentennial Exhibition, Case 4

Case 4: Blockade

American successes in single-ship actions did not seriously impede the operations of the Royal Navy. Its overwhelming superiority in numbers of ships began to tell as more vessels cruised off important ports to intercept U.S. Navy ships and merchantmen. The British officially declared a blockade of part of the Atlantic coast in November 1812, gradually extending it to the entire length of the United States by the end of 1813. Most U.S. warships were bottled up in port, from which only a few were able to slip out. New England was not at first officially blockaded, but its merchant fleet suffered as well.

British embarrassment over its losses to the heavy U.S. frigates was somewhat assuaged by Captain Philip Broke’s defeat of the USS Chesapeake with his HMS Shannon on June 1, 1813. Captain James Lawrence rashly sailed from Boston with a poorly prepared ship and crew and was overwhelmed in just 15 minutes of fighting.

Though not entirely effective, the blockade strangled American seaborne trade.

Charles Heath, Boarding and Taking of the American Ship Chesapeake(London, 1816). Colored engraving. Graphics Division.

Following initial exchanges of fire, Shannon and Chesapeake became entangled, and a British boarding party fought its way aboard the American frigate. Mortally wounded early in the action and carried below deck, Captain Lawrence ordered, “Don’t give up the ship.” His crew was unable to comply, but Lawrence’s words were emblazoned on a battle flag flown by Oliver Hazard Perry during his victorious action on Lake Erie three months later.

James Lawrence (1781-1813). Engraving after a painting by Alonzo Chappel (New York, 1862). Graphics Division.

William Paine, [British men o’ war off Long Island, March 20, 1813].Watercolor over pencil on paper. Graphics Division.

In March 1813, the British extended their blockade to include New York. The unidentified incident depicted in this watercolor took place on the 20th of that month. Paine, a Royal Navy purser, wrote on the verso, “Anchored off the Coast of Long Island we succeeded in drawing off the enemy’s Gun Boats who had taken possession of her.” The reference is to the burning merchantman in the middle background.

Two British frigates and a ship-of-the line represent part of the blockading squadron. The tiny U.S. gunboats were legacies of the Jefferson administration’s 1801-1809 naval cost-cutting measures. Good for little more than harbor defense, they were no match for seagoing warships.

“Journal Private Armed Schooner Dart, Thorndike Symonds master.” Manuscripts Division, War of 1812 Collection.

The blockade could not completely seal the long American coast. A few naval vessels and a regular stream of privateers slipped into the Atlantic. The schooner Dart left ahead of the blockade, sailing from Salem, Massachusetts, on July 16, 1812, for a 24-day cruise. Her targets were enemy merchantmen, but Dart encountered mostly other American privateers in the waters off Maine. More than 500 American privateers were outfitted during the war. A much smaller number of British vessels preyed upon American shipping.

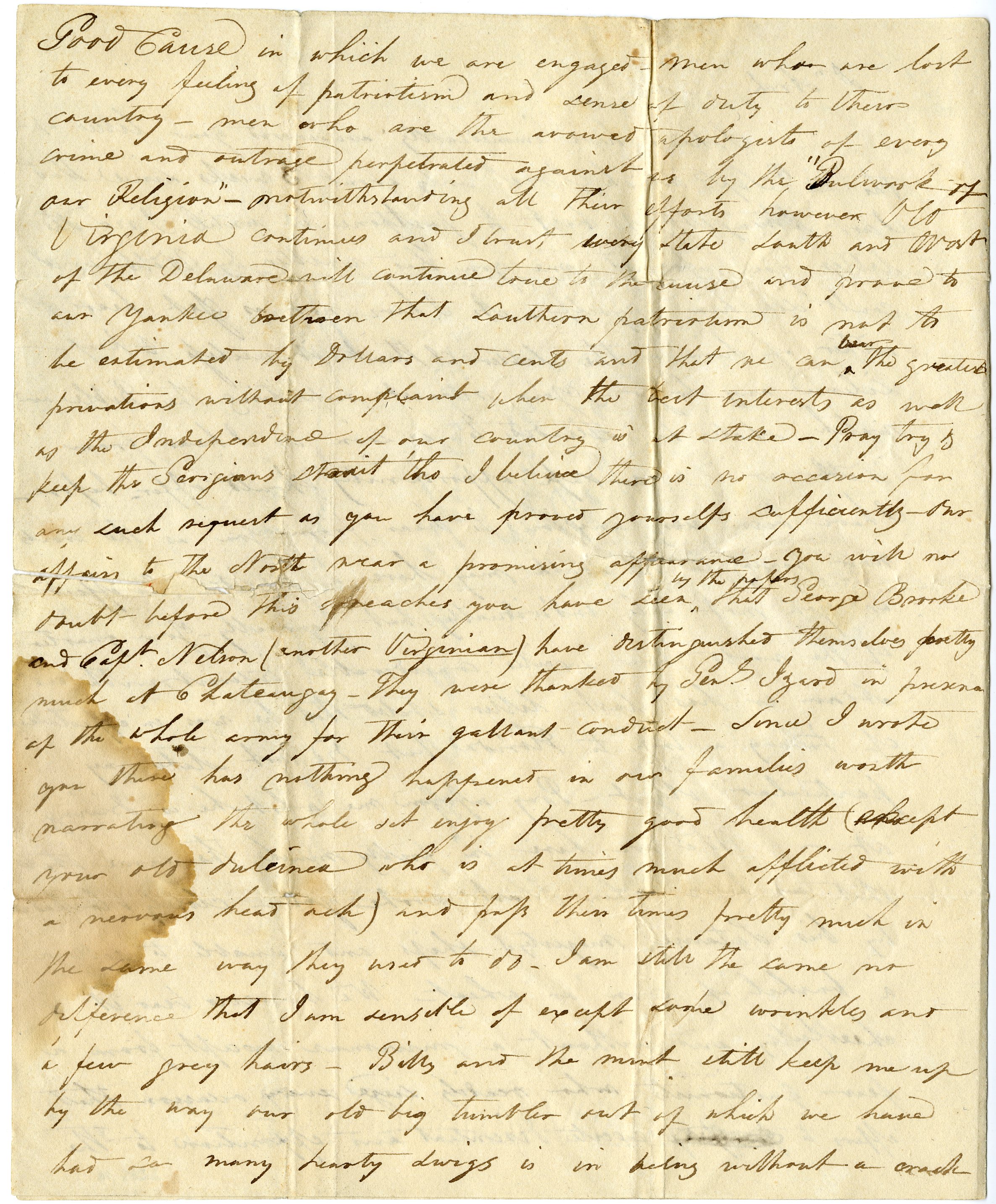

John M. Garnett ALS to Archibald R.S. Hunter, Loretto, [VA?], November 29, 1813. Manuscripts Division, War of 1812 Collection.

Garnett expressed the frustrations of many shippers—that he was “closely blockaded by his Satanic majesty’s ships and unable to sell a bushel of corn or wheat.”

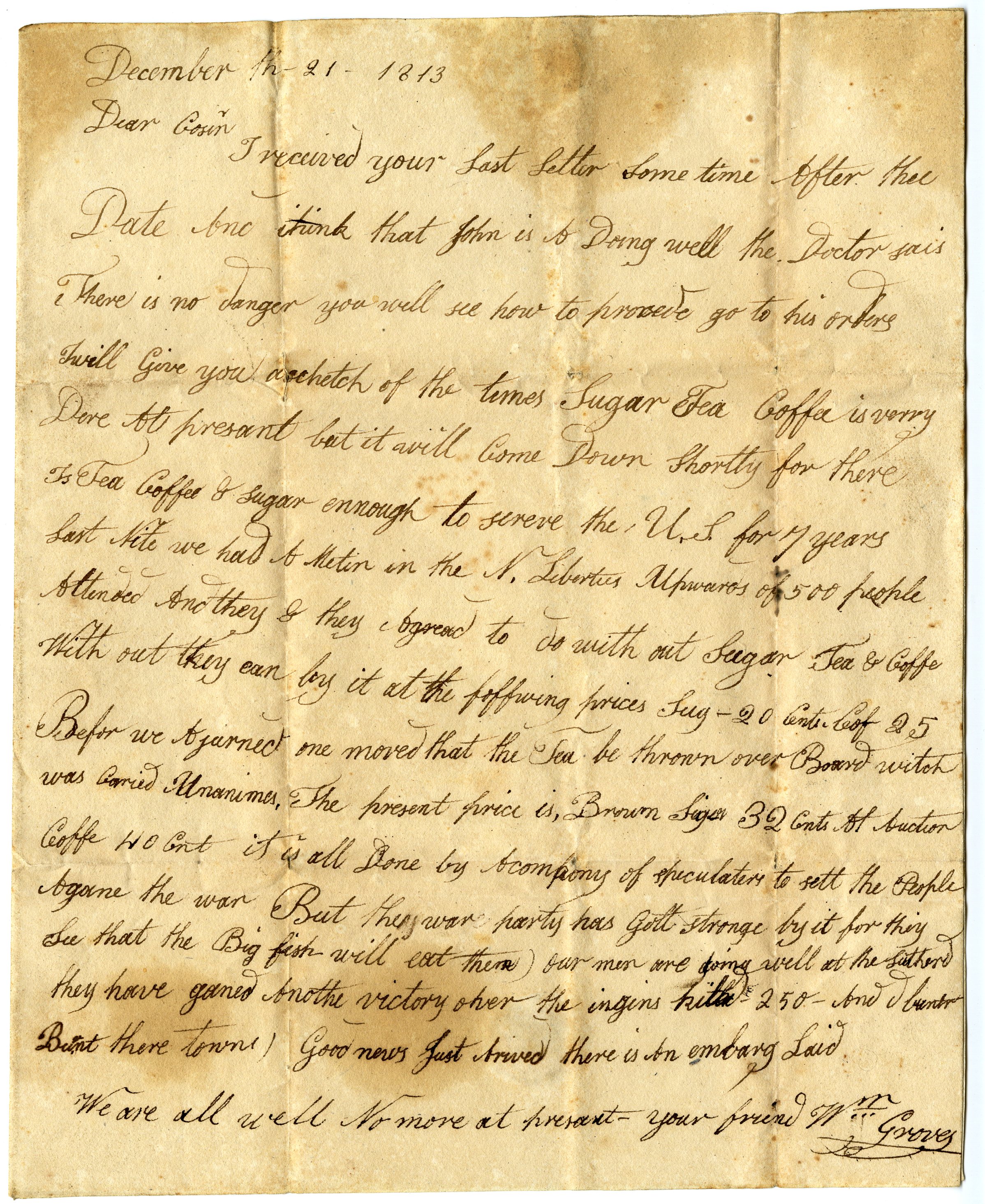

William Groves ALS to William Carner, Philadelphia, December 21, 1813. Manuscripts Division, War of 1812 Collection.

The blockade and captures of American merchantmen at sea aggravated wartime shortages. Speculators made the situation worse. William Groves accused them of ensuring that “Sugar Tea Coffee is verry Dere at present” despite large quantities in storage. On December 20, 1813, five hundred Philadelphians met to protest. They voted to stage their own Tea Party by throwing it into the Delaware River, but there is no evidence of any further action.