No. 56 (Summer/Fall 2022)

City Life

Nothing could be further from the truth. Even in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, one of the most remarkable things about the United States—noted by native-born Americans and foreigners alike—was its pace of urbanization. Perhaps none of the cultural shifts that transformed the United States in the decades before the Civil War were as significant as the growth of large cities. This story of urban expansion is one that the collections at the Clements Library tell remarkably well, both in terms of where items in the collection were produced and what they are about.

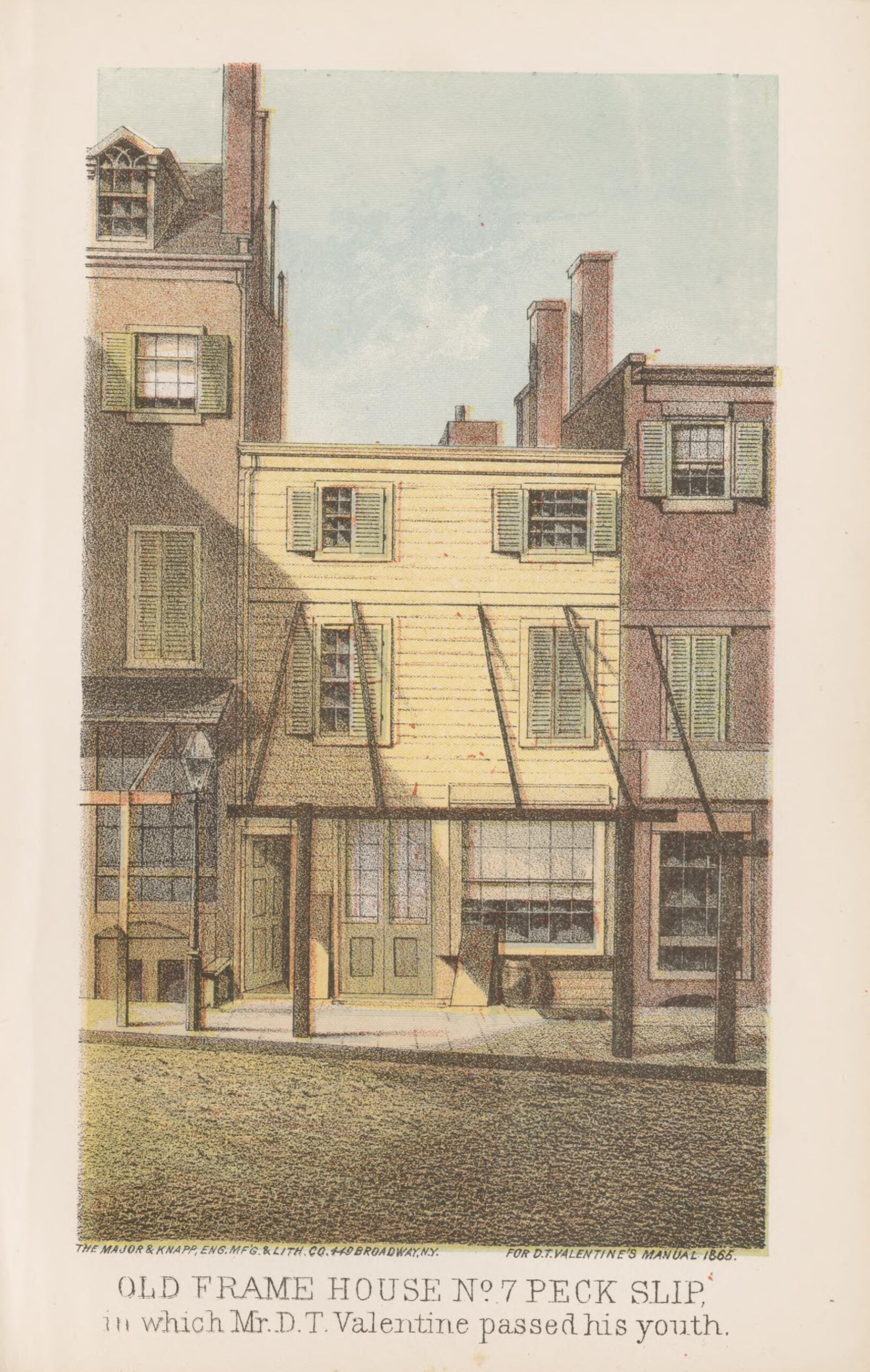

So how fast were American cities growing? The numbers are difficult to believe. The cities of the early United States were compact collections of mostly wooden buildings, of easy walking scale. In 1800, the vast majority of New York’s 60,000 residents lived on the southern tip of Manhattan Island below Canal Street. Similarly in Philadelphia, which was the nation’s largest city, the population was concentrated in what we now call Old City, with some spillover south and north into areas that were then not part of the city proper.

By 1860, Manhattan was home to over 800,000 people, with another 280,000 living in the then-independent city of Brooklyn. Philadelphia had grown from 40,000 in 1800 to over 560,000. What was even more remarkable was the sudden appearance of cities that had been nothing more than tiny clusters of buildings in 1800. Cincinnati grew from under 10,000 residents in 1820 to over 160,000 in 1860. St. Louis was home to only 5,000 people in 1830; three decades later, it had also topped 160,000. More dramatic still were the so-called “mushroom cities” of the West. In the span of 30 years, from 1840 to 1870, Chicago multiplied in size 66 times, from 4,500 to 300,000. San Francisco topped them all. When gold was discovered in California in 1849, there were fewer than 1,000 people living on the peninsula. Three years later, there were 35,000; by 1870, there were 150,000.

With urban growth came urban problems: crime, prostitution, drunkenness, noise, sewage, poverty, fires, rampant inequality, loneliness, and more. Yet cities also offered economic opportunity, excitement, diversity, popular entertainment, and anonymity, as well as ample opportunities for the exercise of benevolence. It’s also the case that even though countless critics warned against city life because of the challenges it presented to conventional morality, for many Americans those challenges to conventional morality were a big part of

the draw.

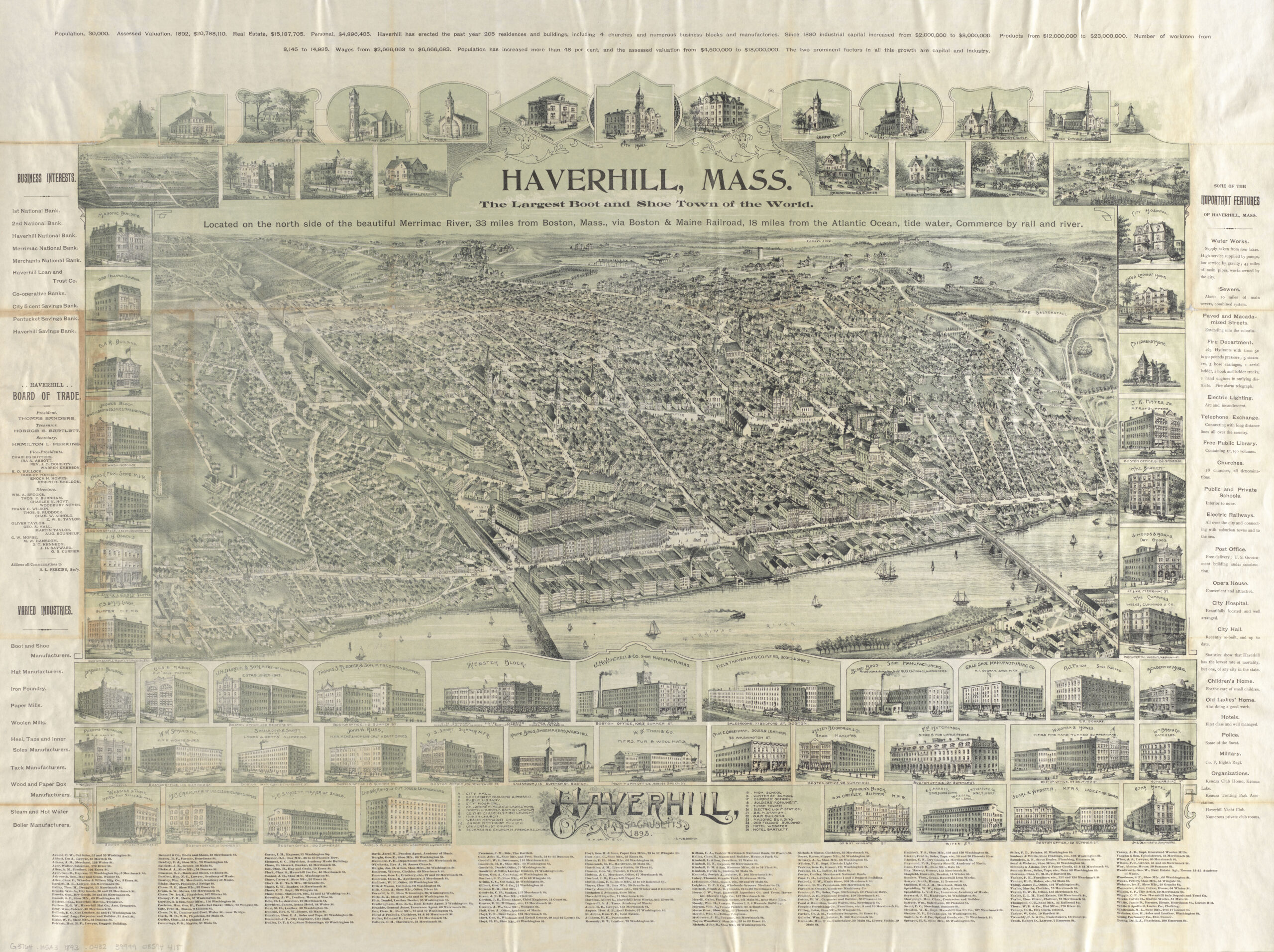

The Clements Library’s collections chart this boom in urban growth (and the increasing diversity of urban populations) in countless ways, from prints to maps to diaries to books. This interest in urban expansion starts early, as you will see in Mary Pedley’s article on the 16th century indigenous settlement of Hochelaga, and extends into the future, as Emiko Hastings describes in her piece on an eccentric vision of the future of Detroit. Perhaps no part of the collection is more focused on the phenomenon of urbanization than our holdings of bird’s-eye views, a genre of printmaking that was very nearly exclusive to the 19th-century U.S. (even though some of its finest practitioners, such as John Bachmann, were from overseas). Bird’s-eye views represented cities from an imagined perspective high in the air, and in the process became the perfect medium for charting urban growth over time. This desire in visual culture to be able to see the city whole extended into photography, as Clayton Lewis discusses in his article on photographic panoramas.

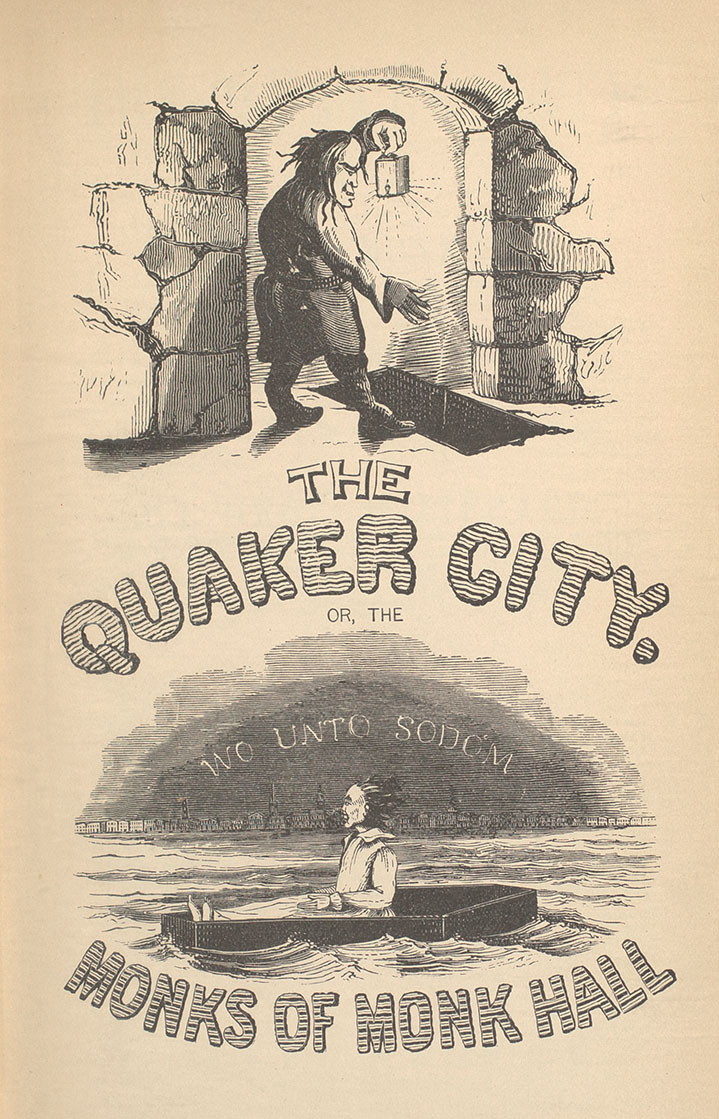

Many of our manuscript collections describe encounters with the city by writers from all walks of life. Their responses, whether positive or negative, were shaped by what they had been told to expect from the urban environment by the flood of print focused on city life. Maggie Vanderford describes one diarist’s long-term encounter with urban growth, as seen through the lens of his work in the shoe business. Urbanization didn’t only alter the ways people lived and played, it wrought profound changes in how people worked. Whether they read children’s books or saw playbills or read almanacs and novels, American readers in the 18th and 19th centuries would have imbibed the powerful message that cities were where things happened, from important political debates to tawdry circus performances. In this regard it is important to mention newspapers, which were perhaps the signature print form of early American cities. Being sufficiently large and industrious to support at least one daily newspaper was an important milestone for any town that had higher aspirations. The Clements Library’s remarkable collection of 18th- and 19th-century newspapers is not as well known as it should be (we are currently seeking resources to create a checklist of the titles and issues that we hold so we can add them to the online catalog).

Any collection of printed Americana from 1750 to 1900 is by definition an urban collection due to the remarkable concentration of all industries related to communication in American cities (and particularly New York) during this time. As the historian David Henkin noted in his book City Reading (New York, 1998), in the 1850s, New York—which only had two percent of the nation’s population—accounted for 18 percent of the country’s newspaper circulation, processed 22 percent of the country’s mail, and received over 37 percent of its publishing revenue. The urban centralization of the printing trades in the United States happened early, as the new nation began to wean itself from dependence on imported print, but accelerated as the 19th century progressed. By mid-century, Philadelphia, Boston, and Cincinnati combined with New York to entirely dominate the national print market. Thus, both in terms of material production and subject matter, the Clements Library’s collections show—as you’ll see in the rest of this issue—that early American history is urban history.

— Paul Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director

Sole Work

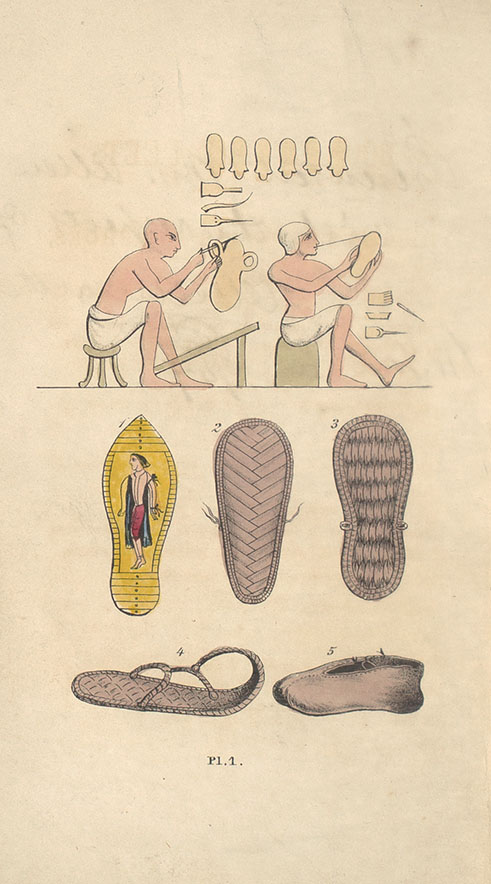

By 1869, approximately 60 percent of shoes and boots made in the United States came from increasingly industrialized hotspots in Massachusetts. When it came to urban growth, shoe production enabled massive expansion for cities like Haverhill, once a tiny cluster of settlements on the serpentine Merrimack River. Fueled by the proliferation of puffing shoe factories, Haverhill blossomed from a population of 3,000 (1820) to 30,000 (1892). By 1893, Haverhill’s Board of Trade proclaimed itself “The Largest Shoe and Boot Town In the World.” And by 1913, Haverhill was nicknamed “Queen Slipper City,” in recognition of its production of 1/10th of the nation’s shoes. According to the maps and statistics, Haverhill’s ascent to shoe stardom seems like a straightforward narrative.

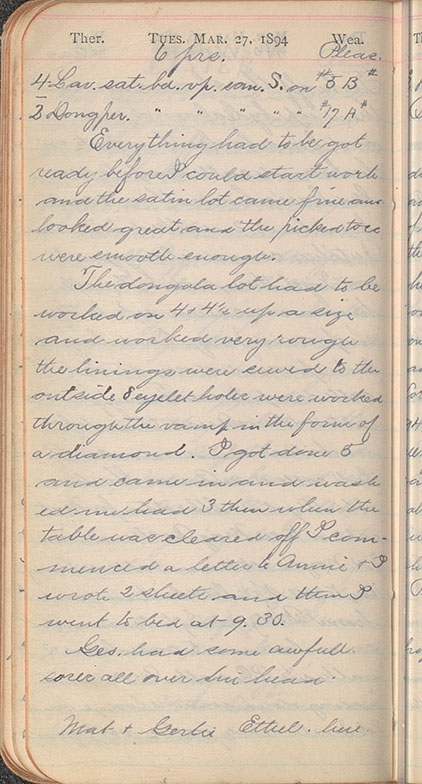

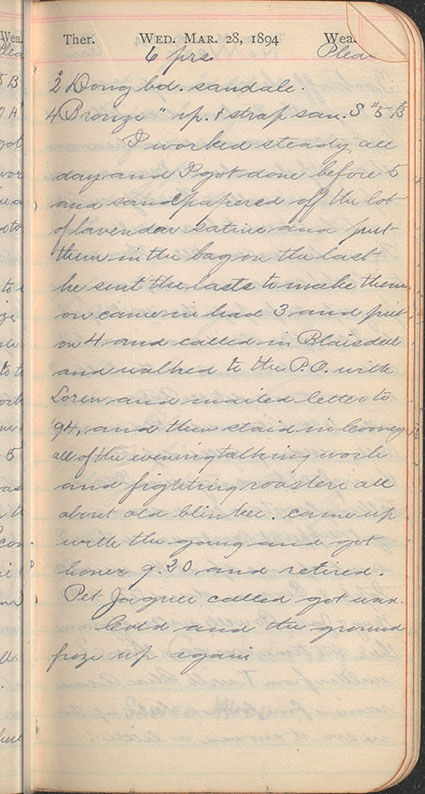

The Clements Library is lucky to hold answers to some of these questions in the rich diaries of Albert Brown Hale (1869-1947). Hale, a shoemaker from the small town of West Newbury, Massachusetts (population 1,300 in 1890), six miles away from Haverhill, was the son of shoemaker Samuel Hale, and went on to join the family business himself. In his 1894 journal, Hale wrote in exquisite detail about the hands-on practices at the family shoe shop. Each day, Hale recorded precisely how many shoes he made (rarely less than four, never more than eight), of what material (often luxurious textiles like lavender satin or white kid leather), and whom they were for (the customer always identified by name). He tracked the weather with the studied devotion of an amateur meteorologist, particularly when the days were rainy and thus muddy (a true concern for someone invested in the durability of delicate satin shoes). The pace of his work was almost comically relaxed, and the intricate details of this labor-intensive work were noted:

January 4, 1894: Got to work at 8, and didn’t hurry much.

January 15, 1894: Got to work at 8:45, and didn’t hurry much.

January 17, 1894: I went to work about 8:45, and was fooling most of the time with father.

March 27, 1894: 4 prs lavender satin sandals…came fine and looked great. The dongola [a leather made by tanning goatskin, calfskin, or sheepskin to resemble kid leather] had to be worked on 4 & 4 ½ up a size and worked very rough. The linings were sewed to the outside and eyelet holes were worked through the vamp in the form of a diamond.

March 30, 1894: Didn’t hurry but took things very comfortable and the shoes came very fine.

After 1894, Hale’s diaries disappeared for 16 years, not resuming until 1912. If Hale wrote entries during these in-between years, the volumes are not held at the Clements and so far remain untraceable elsewhere. From context in the existing diaries, we know that Hale’s life changed tremendously between 1894 and 1912. He married Minnie May Drew (1877–1970) and they had a son (Hazen, b. 1904). And Hale was at last swept up in the tidal wave of industrialization. Around 1900, he moved to Haverhill, a burgeoning city nearly 23 times the size of West Newbury, where he climbed the ladder to the position of supervising foreman at one of the city’s many bustling shoe factories. This transition meant that Hale no longer made shoes by hand, and the previous lists of shoe numbers and types disappeared from his pages. Instead, he oversaw factory teams and created shoe samples for his teams to replicate en masse. The entries in his 1912-1931 diaries provide a firsthand account of the deskilling wrought by industrialization:

December 6, 1923: Made sample Arthur Moore stitch.

February 1, 1924: I got up 5:30…teams worked. Wood had Chicago Fair shoes to work on. Pike sorry he didn’t get in to clean stitcher.

April 8, 1924: Teams worked; I got right up to the floor and was Johnnie-on-the-spot all day.

May 9, 1924: Got up at 6:15am; teams worked, I got right on the job.

Gone were the days of relaxed conversation and family banter from his small-town shoe shop, replaced by a preoccupation with work ethic, staffing, and productivity required by the factory position. In the larger city of Haverhill, Hale no longer knew his customers. His social sphere consisted of other factory workers, and he spent time rereading his diaries from previous years. His skillset transformed from artisanal handicraft to corporate management.

What I really love about teaching these diaries, though, is this: students are instantly fascinated not only by what Hale wrote, but by what he left out. Thirteen years of diaries reveal exhaustive data about what Hale did, yet very little about what he felt. As one history student wrote, Hale’s entries left him frustrated with questions about how Hale (whom the student affectionately designated a “total shoe nerd”) actually experienced the seismic cultural change which occurred between 1894 to 1912. “Was factory work truly a miserable, hopeless career?” the student asked. “Did workers and their families ever look back and reminisce on better days before working in factories? Was there anything that brought everyday people sustainable happiness?” Powerful questions, to be sure, but ones that Hale’s diaries do not explicitly answer. Students wrestled with the lack of information about Hale’s feelings, and were particularly concerned about the extent to which his transition to deskilled labor affected his happiness.

The more I think through the Hale diaries, the more I feel that preparing students for the possibility of textual resistance (“There’s no answer!” or, “It’s not the answer I want!”) is a crucial step in teaching them to do research on how an absence or silence exists in any historical text. Hale’s diaries function in the classroom not only as practical historical studies of the jaggedness of industrial progress in turn-of-the-century Massachusetts, but also as evidence for the ability of “exhaustive dailiness” to communicate macro-narratives. They can offer students the opportunity to practice thinking through complicated texts that refuse to confirm pre-established conclusions, and instead teach us what questions to ask. For most University of Michigan students for whom an urban environment is already familiar, Hale’s voice offers the chance to share, in a small way, a pre-industrial mode of living, and to reflect upon the professional and personal experiences of past generations during periods of great change. And for those students undergoing the transition from a small, rural high school to the teeming Ann Arbor metropolis, history reminds them that they are not alone.

—Maggie Vanderford

Librarian for Instruction and Engagement

Detroit, The Airship City

While sources describing cities of the past can be found throughout the library collections, another way to view urban history is by looking at predictions of the future. In his self-published Poetical Drifts of Thought, or, Problems of Progress (Detroit, 1884), Lyman E. Stowe (b. 1843) envisioned the city of Detroit in the year 2100.

It would be difficult to summarize the exuberant and wide-ranging contents of Poetical Drifts of Thought, which includes discussion of “The Mistakes of the Christian Church” and poems on subjects from religious faith to scientific progress, astronomy, evolution, technological innovations, racial equality, and the Civil War. Stowe’s thoughts on future technologies bore a striking resemblance to later science-fiction tropes, including flying machines, the absorption of food in a gaseous form, and even instantaneous travel “on the electric current with the speed of thought.” The final section of the book was devoted to the past, present, and future of Detroit, the “City of the Straits.” It began with six pages of prose about the city’s population and resources, likely drawn from printed sources such as city directories and newspapers.

The first poem on “Detroit in the Past” gave a brief overview of the city’s history, including the Indigenous people who first lived in the area, the arrival of French and English settlers, and a section covering Pontiac’s siege of Detroit in 1763. The second poem, “Detroit of the Present,” which he noted could be sung to the tune of “Yankee Doodle,” provided an upbeat description of the rapidly-growing city, including bustling businesses and factories, the booming real estate market, parks and riverfront views, and famous landmarks such as the Soldiers’ Monument and the Detroit Opera House. This text was accompanied by a three-foot-long fold-out view of the Detroit riverfront, based on a photograph taken from the balcony of the Crawford House, Windsor.

Stowe himself was a Detroit businessman, being at various times a subscription book agent, a publisher, and the owner of a shop that sold pictures, frames, and clocks. According to the Detroit city directories from 1880 to 1883, Stowe’s shop was located at 121 Gratiot Avenue, near what is now the Skillman branch of the Detroit Public Library.

Lyman E. Stowe’s store; Stowe is the tallest figure in the back row. Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

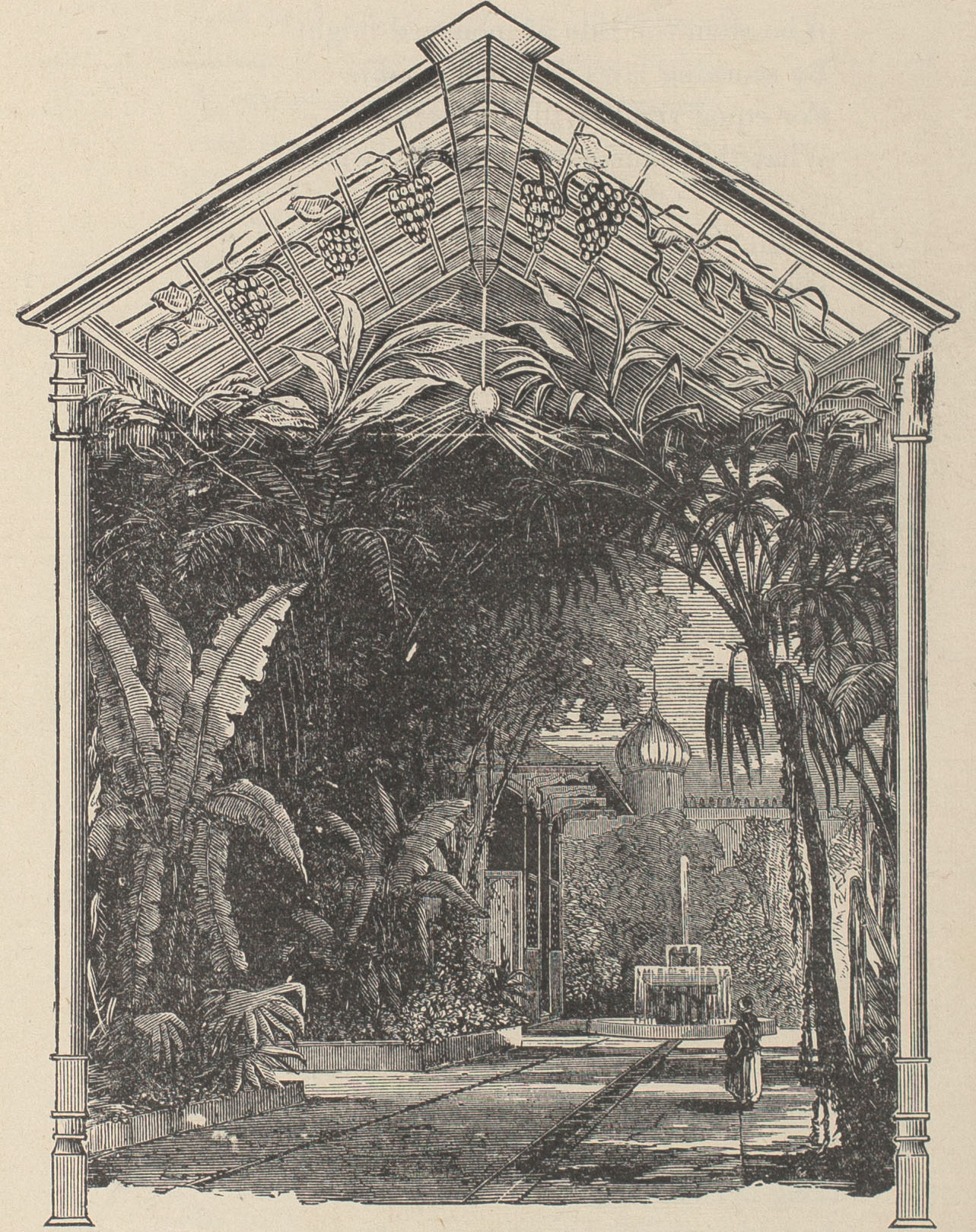

In “Detroit of the Future,” Stowe predicted the city’s anticipated wonders, including both technological innovations and great societal changes. He thought the city of Detroit in 2100 would be enclosed, “covered with iron and glass for 20 miles square.” With geothermal heat and electric lights, the residents would experience “perpetual summer day, and tropical fruits and flowers growing the year around.” By that time, the city itself would extend the full length of the river on both sides, with a population of more than 1.5 million people. Factories would have moved outside the city, to which workers would travel through pneumatic tubes or in aerial ships. Stowe’s utopian vision included the end of poverty and hunger, as “superfl’us wealth has had its fall, And equal rights now govern all.” Indigence and crime would be abolished, removing the need for police, lawyers, judges, prisons, and poorhouses.

Stowe’s ideas about electricity, flying machines, and other advances may have drawn inspiration from his vast and eclectic reading, including poetry, novels, newspapers and magazines, and a vast range of nonfiction books including Alexander Winchell’s Sketches of Creation (New York, 1870), Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (London, 1859), and Orson Squire Fowler’s volumes on phrenology. According to his introduction, he attributed his enjoyment of reading to popular fiction, “that much abused little dime novel.”

In compensating for a lack of early education, he credited “the great public educators, the daily and weekly papers” for providing him with much information. The breadth of his reading can be seen in the list of sources provided at the end of the book as well as the citations given throughout the text. However, he cautioned that while he would always try to give credit where it was due, he had “read so much that I can hardly say where all of my ideas came from, or what is my own or what I have borrowed from others.” To make up for this, he inserted a pair of large quotation marks in his introduction and asked the “fastidious reader to place them where they belong.”

“A scene in Detroit in the year 2100, looking down Boulevard ave.—the City covered with iron and glass for 20 miles square.” Lyman E, Stowe, Poetical Drifts of Thought (1884).

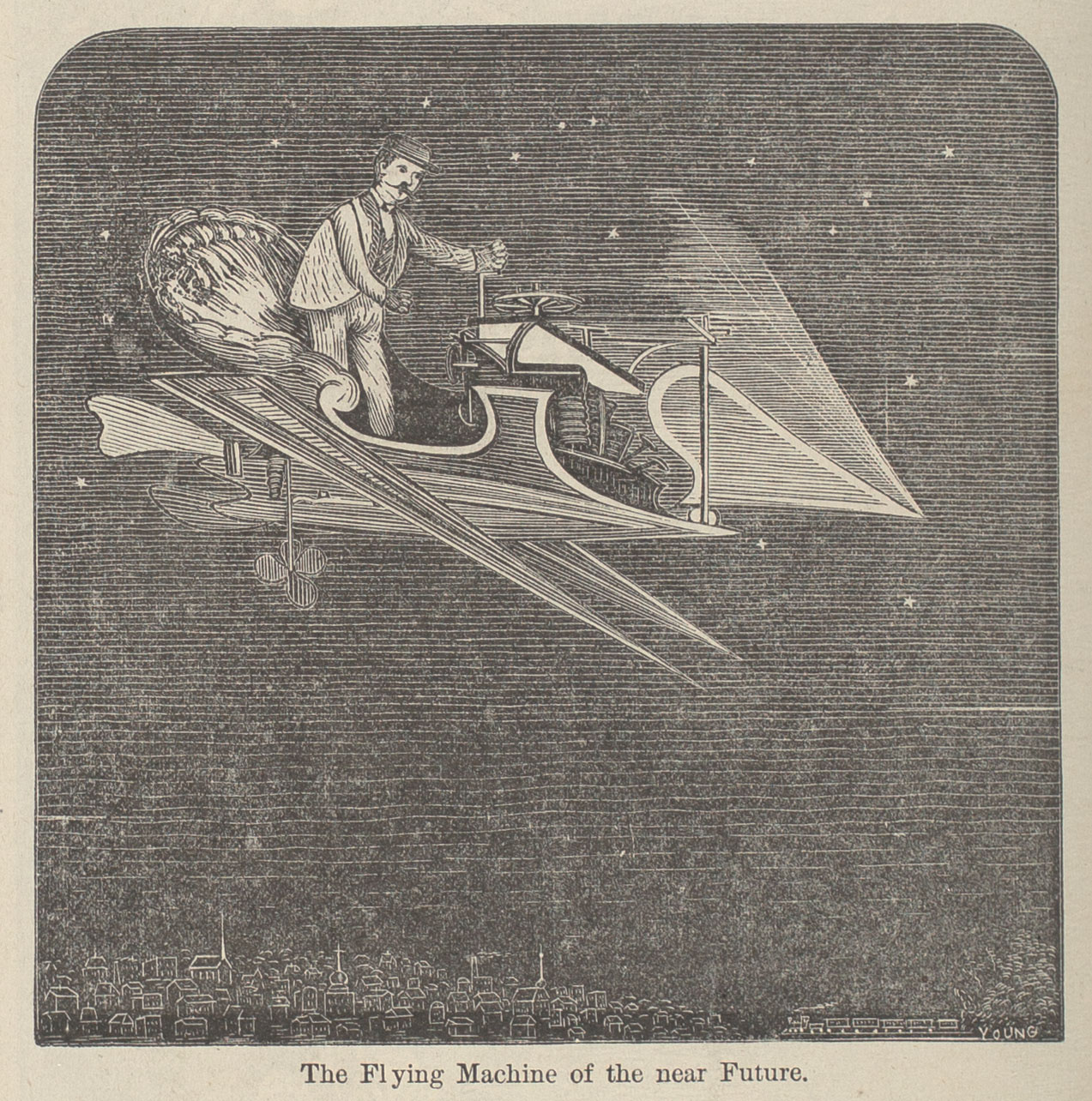

“The Flying Machine of the near Future,” Poetical Drifts of Thought (1884).

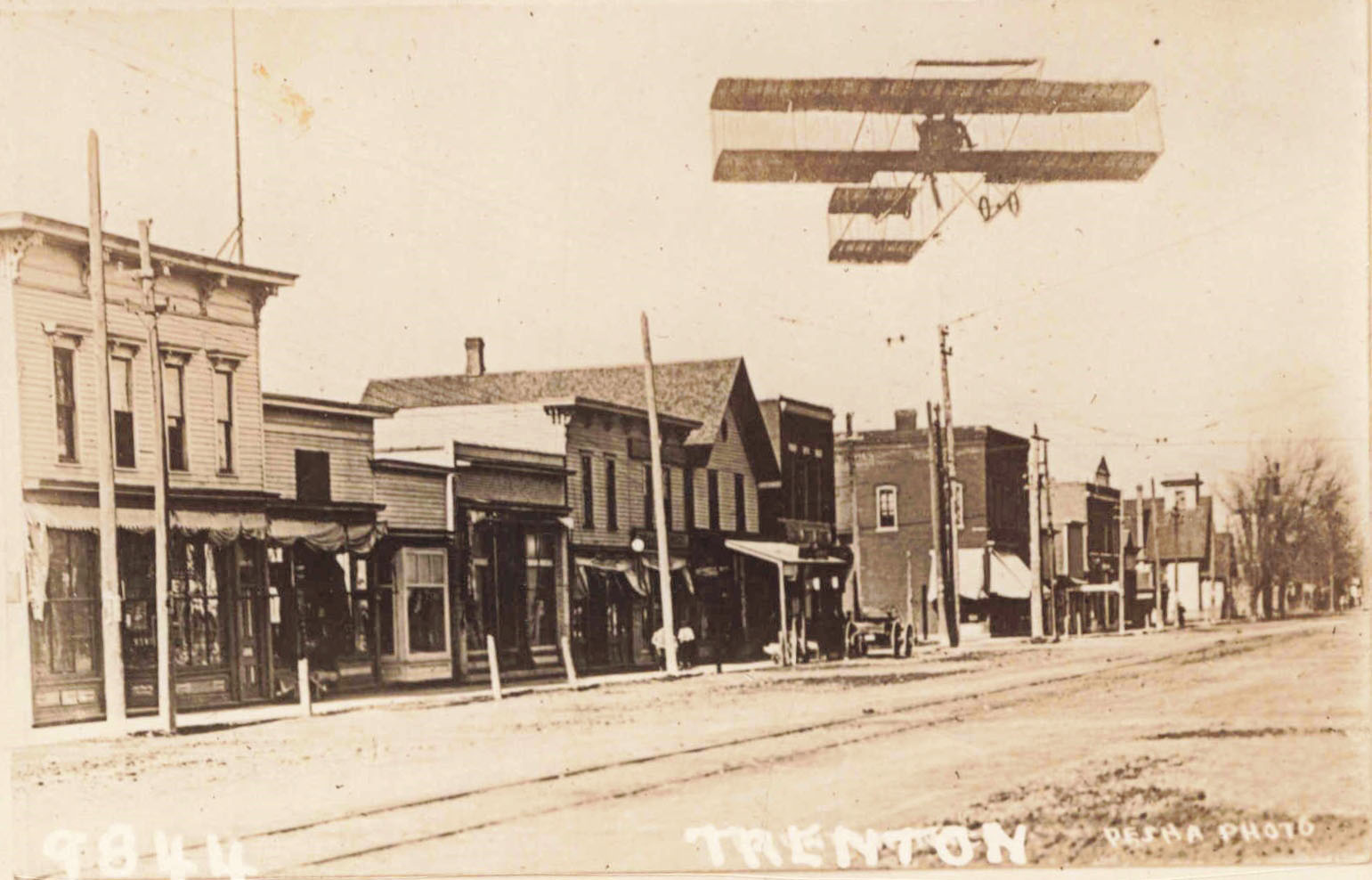

David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, real-photo postcard by Louis James Pesha, 1911.

David V. TInder Collection of Michigan Photography, real-photo postcard, 1910.

Poetical Drifts of Thought is illustrated throughout with a mixture of original wood engravings and stock illustrations borrowed from other sources. The engravings commissioned by Stowe are signed by “E. A. Young of Detroit.” Stowe did not seem entirely satisfied with the outcome of Young’s work, commenting under one image that “The above cut misrepresents the author’s idea. It is a mistake of the engraver, that we had not time to correct.” The caption for the flying machine notes: “The above cut is not supposed to be an accurate description of the future flying machine. The author of this work [Stowe] has in contemplation a flying machine that he believes will work perfectly, and which he will soon test.” Engraving blocks for many of these illustrations are now at the American Antiquarian Society in the Lyman Stowe Collection of Matrices.

Stowe was not the only one to envision airships hovering in the skies above Detroit. In the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, there are several examples of 20th century real-photo postcards that depict Detroit with aircraft of various kinds flying low over the city. However, these flying machines have been cut and pasted into the skyline of the city, adding visual interest to the postcard and suggesting a more urbanized and futuristic cityscape. For example, the postcard “Detroit the Airship City” includes an airship as well as an airplane, unintentionally echoing Stowe’s visions of a futuristic Detroit.

Another postcard from Trenton, Michigan, takes a more cynical view of the future of flight, contrary to Stowe’s vision of social equality. This postcard, depicting a pasted-in airplane flying low over a street scene, included a printed poem under the image that forecasted an increasing class divide with the rise of air travel. It read:

In nineteen hundred and sixteen

We all shall be flying—perhaps!

And racing with sea-gulls and

thunder clouds

In dizzy aerial laps

We’ll go to our business each

morning then

In speedy aeroplanes,

And move our dirigible baloons

To steeples or weather vanes

Then all will be joy to the chaps who fly,

But days full of fear and dread

For the common people who have

to dodge

Things dropping from overhead

Stillson wrenches and gasoline cans,

And champagne bottles and corks

Will cover the buildings and fields

and streets

And bury the chap who walks.

Although present-day pedestrians in the “City of the Straits” do not enjoy fantastical views of airships and biplanes overhead, nor need they scramble for shelter from falling debris, perhaps some of Stowe’s other visions will yet come to pass by the year 2100.

—Emiko Hastings

Curator of Books

An Early North American City

When we think of urbanization in North America, our thoughts generally turn to the cities founded by European colonists in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. We often forget that European adventurers who preceded the colonial settlers encountered the cities of Indigenous inhabitants of North America. Reports and images of these urban sites were published in Europe and constitute some of the earliest descriptions of North American cities.

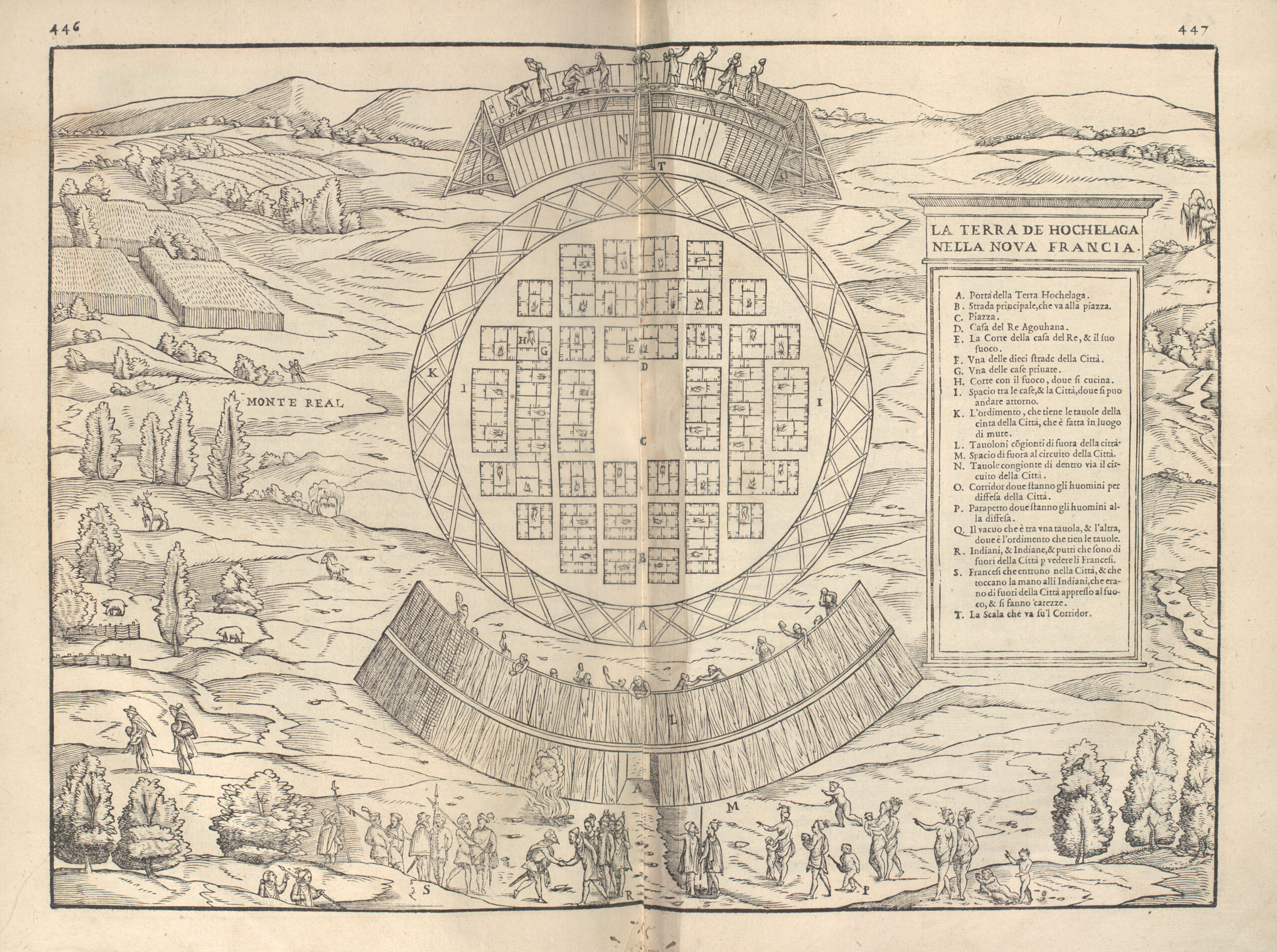

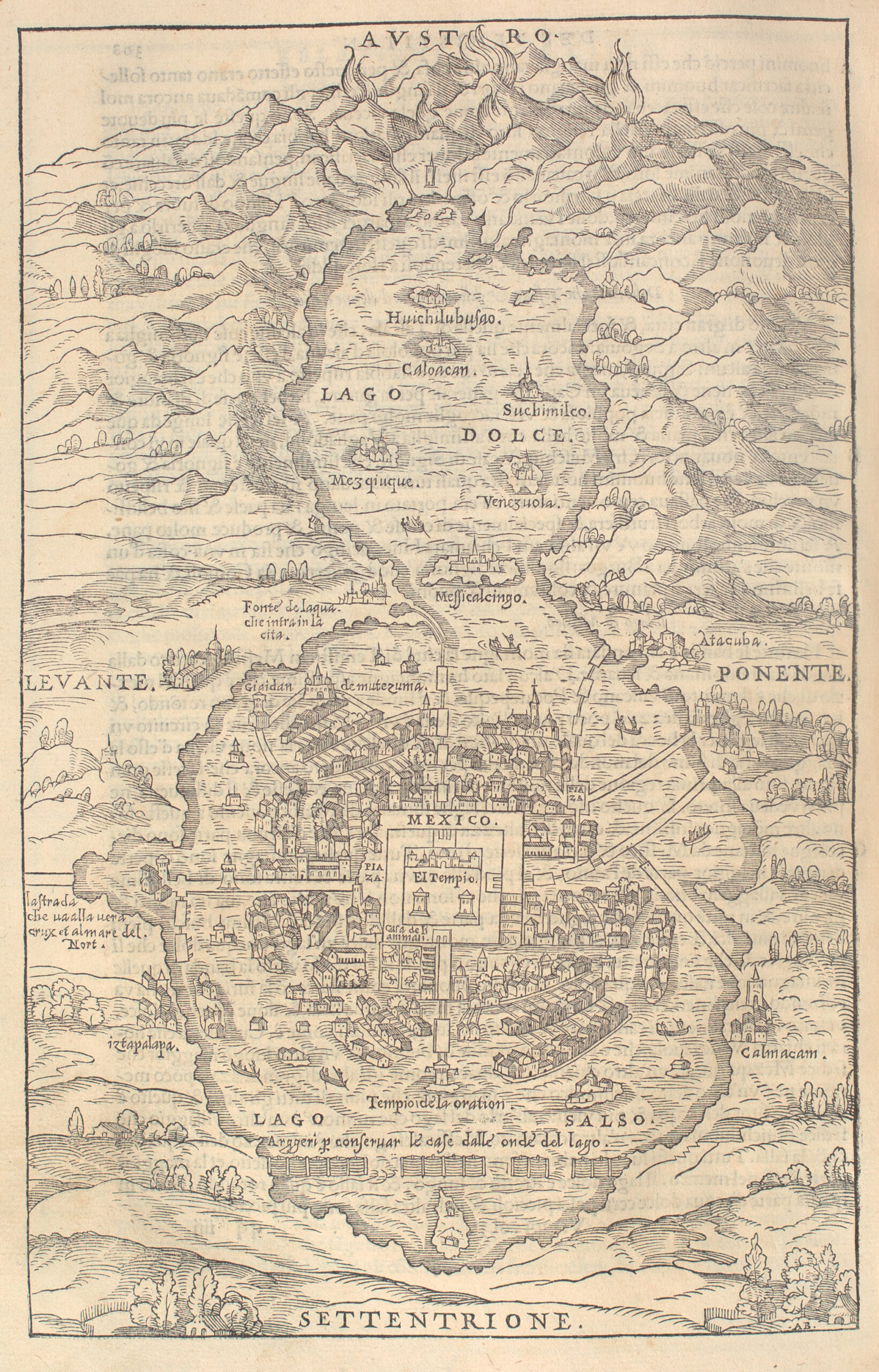

The Clements Library boasts two of these early Native American city plans. The first is the well known woodcut image of Temixitan (i.e., Tenochtitlán, present day Mexico City), published in La Preclara Narratione de Ferdinando Cortese (Venice, 1524) by Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), and also by the Venetian printer, Giovanni Ramusio (1485–1557) in his translation of navigation and voyages of European travelers throughout the world, Delle Navigationi et Viaggi Raccolto (Venice, 1583). The second plan, less well known and also included in Ramusio’s collection, illustrated a translation of Jacques Cartier’s report of his second voyage to North America, to the region of the Saint Lawrence River. Among the many things Cartier (1491–1557) encountered was the Native American town of Hochelaga, near the river and abutting a mountain christened by the French as Mont Royal, later to be known as Montréal. Of the two images of Native American cities, Hochelaga is less well known and deserves a closer look. Not only does it preserve the early history of a city that loomed large in the fur trade, the Seven Years’ War, and the American Revolution, it also symbolized the imposing presence of the Indigenous groups living in a broad area from the mouth of the Saint Lawrence to the Great Lakes.

The engraving entitled “La Terra de Hochelaga nella Nova Francia” (The Land of Hochelaga in New France) comprises a plan of the town, with enlarged views of the surrounding fortification, as well as vignettes of the encounter between the residents of Hochelaga and their surprise French visitors. The whole was probably laid out and engraved by Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-ca. 1565), under Giovanni Ramusio’s supervision.

Cartier, a native of St. Malo in Brittany, France, sailed under the aegis of French King François I (1494–1547) to search for the vaunted Northwest passage to Asia, or, failing that, to find what riches he could in the so-called New World. During his second visit to explore the bay and mouth of the Saint Lawrence River in 1535 and 1536, he and a number of his men traveled up the Saint Lawrence, reaching the site of Hochelaga on the island of what is now Montréal, in October of 1535.

A narrative of this journey was published in Paris in 1545 as Brief Recit, & Succinte Narration, de la Nauigationi Faicte es Ysles de Canada, without illustration. The plan of Hochelaga appearing in Ramusio’s volume includes images that conflate several moments in the narrative into one scene. The text describes the French journey by boat along the Saint Lawrence to Hochelaga where a tumultuous welcome was given by many (Cartier’s narrator says a thousand) men, women, and children, who greeted the strangers with cries of joy and a desire to touch them, followed by gift giving and noisy festivities throughout the night. The next morning Cartier and 25 of his men were led by three residents of Hochelaga through remarkable oak forests along four or five miles of well beaten path to the town, which they found in the midst of ripe grain fields close to a mountain which they named Mont Royal (Monte Real on the Ramusio plan). There, a chief from the town bade them pause to enjoy a fire and more gift giving before entering the town itself. The French remarked on the round layout of the town, surrounded by a wall of wooden pickets in three ranks, two leaned against each other in pyramidal form, and a perpendicular rank that created a defensive platform from which the inhabitants could throw stones to defend the city. Once in the town, they observed the distinct layout of ten streets, regularly arranged around 50 wooden houses, each house having many rooms, a courtyard for a cooking fire, and an attic for storing grain.

Temixitan, from Giovanni Ramusio’s Delle navigation et viaggi . . . (Venice, 1583).

In the town the French were once again greeted warmly and conducted into the central plaza where a fire was lit. Children and women with babes in arms arrived and gathered round to touch the foreigners, while crying with joy and encouraging the Frenchmen to touch their children. After the women and children withdrew, the men of Hochelaga sat down in a circle around the French; some women returned with skins for the French to sit on as they watched the king or grand seigneur of Hochelaga, Agouhana, a man of about 50 years old wearing a large stag skin and wreath of red hedgehog skins, carried in on the shoulders of nine or ten men. He was seated next to Cartier, who observed that the king was afflicted with palsy. Agouhana asked by gesture that Cartier rub his arms and legs. After Cartier obliged, Agouhana gave him his wreath and desired that many of the town’s blind and very old residents be brought into the presence of the French. Cartier recited the “Incipit” (“In the beginning . . .”) from the Gospel of St John, touched the afflicted, and read from the Passion of Jesus, which silenced the crowd, who imitated the gestures of Cartier as he spoke. The French distributed small gifts and tokens to the residents; then Cartier ordered trumpets and other musical instruments to sound, causing further joy. When the French began to return to their boat, some Hochelagans escorted them the short mile to the top of Mont Royal, from which they could see, about 30 leagues around. After learning what they could via signs and gestures of the surrounding countryside and its resources, the French continued toward the river with an escort of Hochelagans, some of whom carried several fatigued Frenchmen on their backs to the boat.

While Cartier’s Brief Recit only gives the French view of the encounter with Hochelaga, it does provide its European reader with a description of a gracious people, warmly joyous in welcome and caring in their sendoff. It can only be imagined what the inhabitants of Hochelaga made of the curiously dressed Frenchmen or what they understood of their unusual language. The fact that the inhabitants of the land of Hochelaga lived in a town reinforces the meaning of “Canada,” the Iroquois- Huron word for “town, village,” the name ultimately applied by Cartier for this region north of the Saint Lawrence. City living was nothing new to these residents.

Abraham Ortelius’ well known atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, (London, 1606) contains this map of the region named La Florida by the Spanish, on which Native American settlements are marked with the city symbol used on European maps.

The image of Hochelaga, like the images of Temixitan / Mexico City, should remind us that “cities” are not the preserve of the European colonist but a phenomenon of human beings living together—satisfying the need for family, shelter, communal access to food, and shared participation in cultural practices such as prayer and story-telling. Cities take many forms as they serve to answer these human needs, and Hochelaga takes its place among them.

— Mary Sponberg Pedley

Assistant Curator of Maps

Lost In The Crowd

I have always envied people who seem to have a secure sense of direction. Myself, I am easily turned around and once got so lost that I had to casually ask someone the way to “downtown” because I didn’t even know which city I was closest to anymore. In an era before smartphones and Google Maps, it was a completely bewildering experience to be adrift and unmoored in space. Where am I?! It’s a question people had to ask themselves much more frequently in the past than we do today.

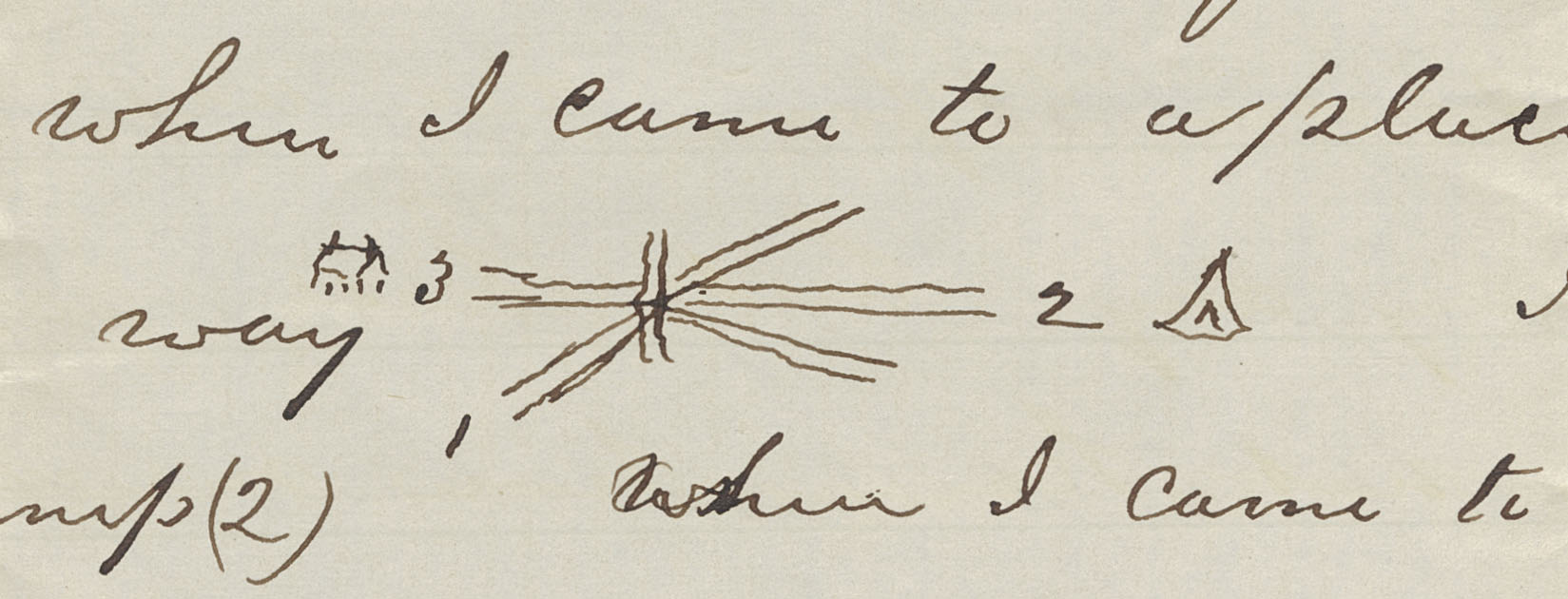

Nineteenth-century travelers writing of their journeys could be quite frank about losing their way. In 1848 George Turley visited Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and wrote home about his arrival. Staying at a “public house” near the steamboat landing, he admitted, “I have not a chance of traveling about the city much, for I get lost so often. I got lost today and went about a mile out of my way.” Living in an age where our phones can readily pull up our exact longitudinal coordinates and our cities are rife with street and traffic signs, it can be easy to forget just how perplexing it might have been to make your way through an unknown space in earlier times. A wrong turn could take up your entire day, and people grew frustrated trying to navigate new cities. Civil War surgeon George T. Stevens wrote to his wife Hattie on January 12, 1862, about one such mishap while he was stationed in Washington, D.C. “I had gone half a mile before I found I was wrong,” he harrumphed, “and when I was at length convinced of my mistake I could not for a long while realize where I was.” He even drew a sketch of where he went wrong, highlighting the offending intersection.

A perplexing intersection in Washington, D.C., got the better of Civil War surgeon George T. Stevens in 1862.

Reading through letters, it certainly seems that getting turned around in cities was a frequent affair. When Julia A. Wilbur went to Alexandria, Virginia, during the Civil War to work with freedmen’s education and relief programs, she wrote extensively back to her colleagues in the Rochester Ladies’ Antislavery Society. In October 1863, she commented on “Grantville,” a quickly growing neighborhood largely populated by freedmen and women. “There are so many houses there now,” she exclaimed, “that I got lost, just as I would in any other city.” More than the organization of streets, access to shops or services, or population density, it was her getting lost that made this evolving space feel urban.

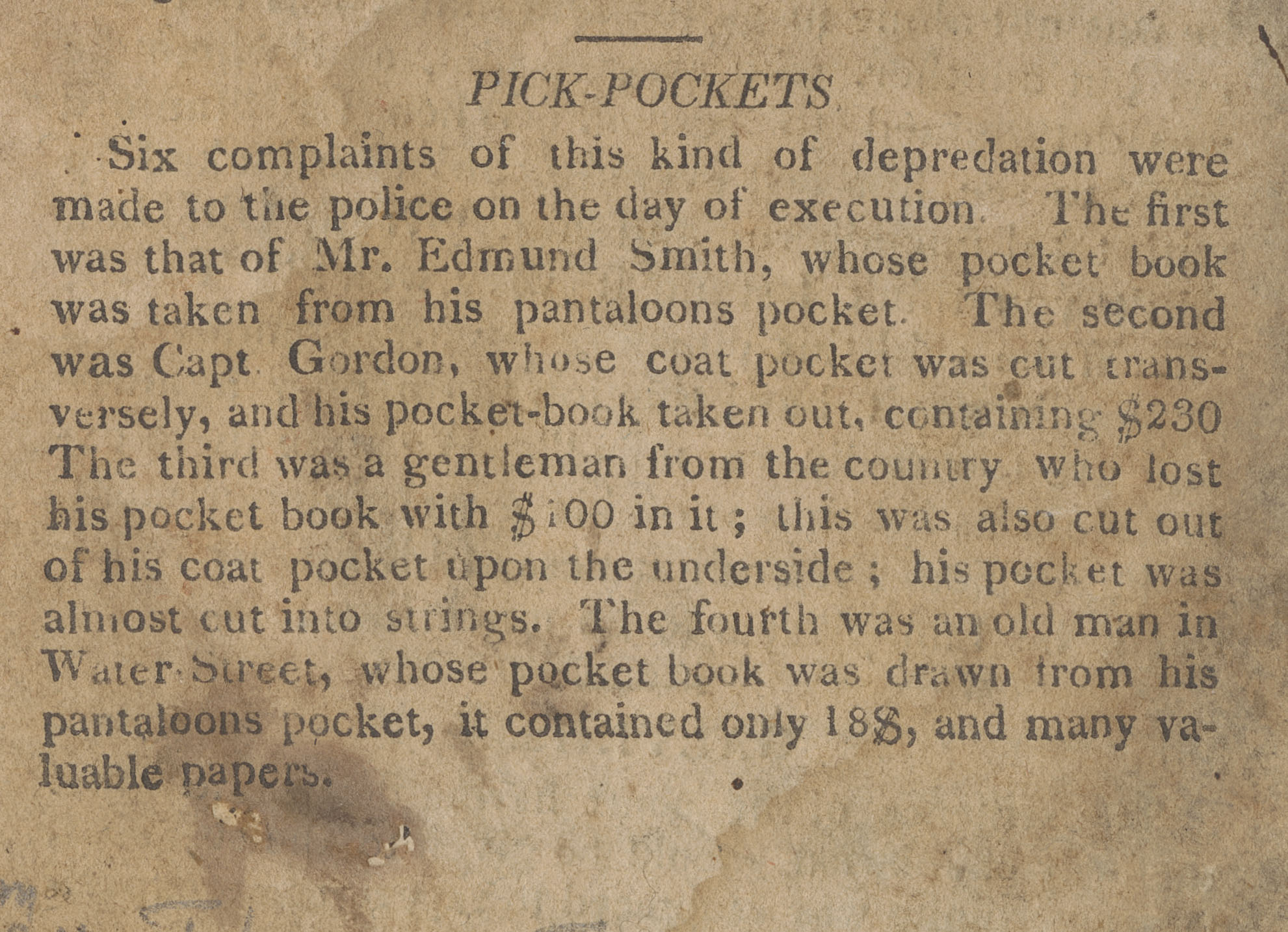

People didn’t just comment on misplacing themselves in the city, but also their belongings. You not only had to keep tabs of where you were, but where your wallet and pocket watch were, too. George Ellington’s The Women of New York, or, The Under-World of the Great City (New York, 1869) laid out just how such things might go missing: “It is a very common and a very old practice for a lady pickpocket to request a gentleman sitting next to her in an omnibus or a car to raise or lower the window. . . . While he is in the act of performing this service, the ‘lady’ relieves him of his watch, and shortly after leaves the stage and is lost in the crowd.” Scanning through 19th-century police reports, notes about petty larceny and pickpocketing pepper the pages. The Clements’ copy of the Buffalo, New York, police docket from 1877 records items stolen from houses, rooms, sleighs, and stores, as well as from right under your nose. George Kearch reported that “there was stolen out of his coat pocket at 700 Washington St about 1030 yesterday AM a 5 Dollar bill.” He suspected two rag pickers, whom he described in great detail, noting their hair, build, clothing, and even the state of their teeth. Whether guilty or just suspected based on social prejudice, there’s no indication the police arrested the two men, suggesting that just like those described in Women of New York, these possible pickpockets melted into the anonymous crowd of the city.

Mingling in crowds meant you had to keep a close eye on your belongings. This warning accompanied an pamphlet about a public execution where pickpockets were hard at work, A True Account of the Confessions, and Contra Confessions of John Johnson (New York, 1824).

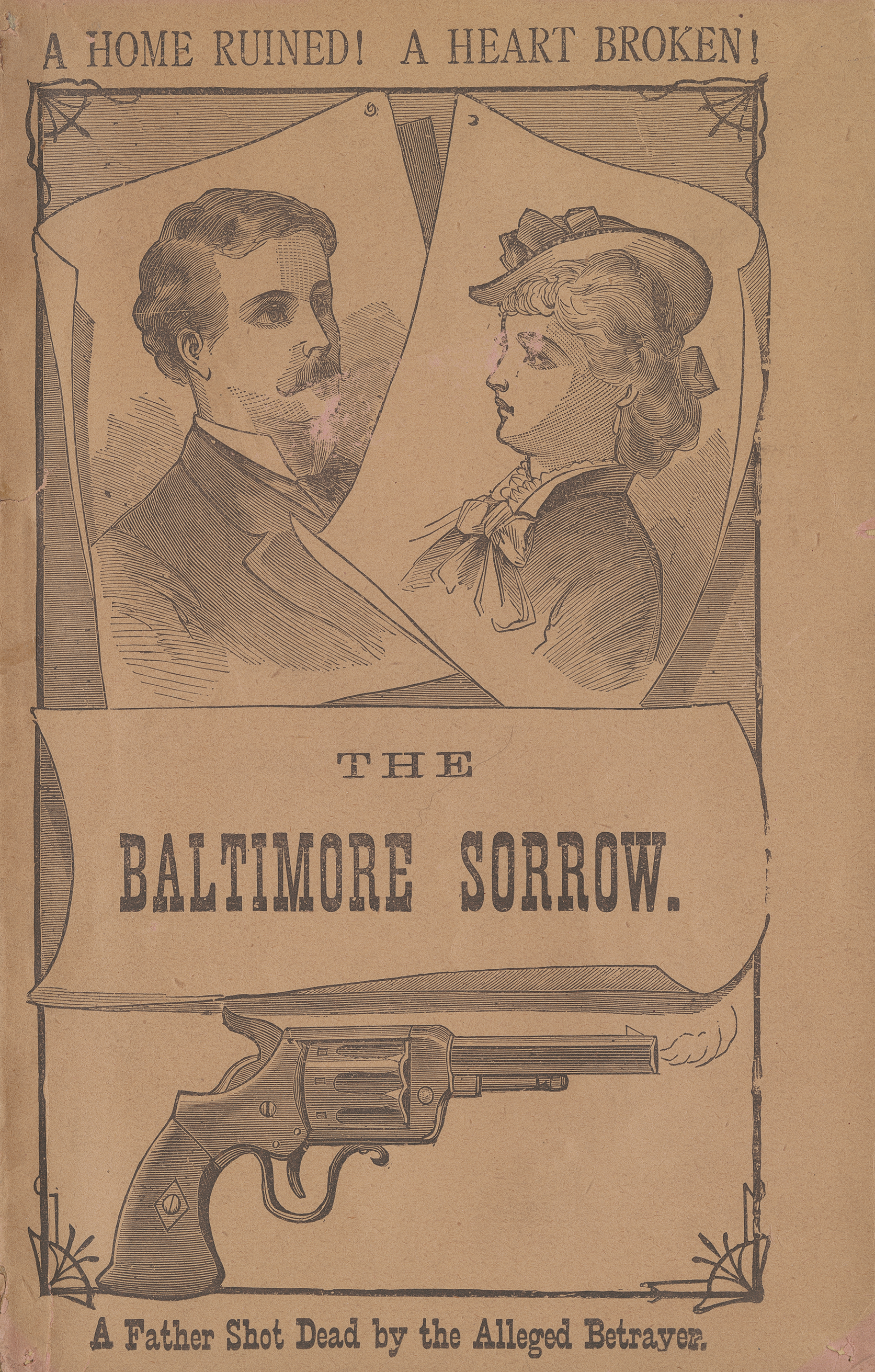

Faceless masses concerned 19th-century Americans. In an era of rapid social change and urban growth, the city felt especially unmoored and writers warned of the potential hazards lying in wait. “The Emigrant is released from the social inspection and judgment to which he has been subjected at home,” Charles Loring Brace wrote in The Dangerous Classes of New York and Twenty Years’ Work Among Them (New York, 1872). Luckily for the unsuspecting, he continued, “the machinery for protecting and forwarding the newly-arrived immigrants, so that they may escape the dangers and temptations of the city, has been much improved.” Cities would ensnare the unsuspecting, lead astray the desperate, or offer up opportunities for ne’er-do-wells, such books suggested. While sensational printed accounts of crime or poverty underscored broad anxieties about how society functioned in cities, everyday people worried about loved ones moving there on a smaller, more human scale. “On the 7th of Nov. 1863 I parted with my youngest son Henry, a lad 19 years old to go to a greate city and battle the temtations that will be placed before him,” Royal Danforth of Raynham, Massachusetts, fretted in a letter from the Duane Norman Diedrich Collection. “When I think of him and compare his case with others that have fallen, I tremble for his safety.” You could not just get lost physically in the sprawling city, but morally, too.

The orderly scene portrayed in this 1856 lithograph of Broadway by Julius Bien likely masks what was a confusing whirl of activity happening at street level.

But when you don’t want to be found, getting lost can be a blessing. In his autobiographical recounting of his escape from enslavement, Frederick Douglass remarked, “the chances of success are tenfold greater from the city than from the country.” Having access to transportation options, mingling in crowds, and being in a place where your social connections were more diffuse, could mean you might find an opportunity to slip away. Even those living in freedom could use the city as a protective cloak. In 1813 James Craig was searching for Sophia Elizabeth Feranze, a mixed-race woman living in Philadelphia who owed him money. As he reports in a May 29, 1813, letter in the African American History Collection, he thought her “slippery as an eel,” and despite his efforts to lean on his contacts he could not “obtain any other information than she lives with a Monsr. Longue, or Largee a french man . . . this is all I can learn about her.” Amidst the ebb and flow of residents, visitors, merchants, or sailors, people who did not wish to be found could try to lose themselves and with any luck maybe make themselves anew.

The excitement of an arriving ship increased the chaos of navigating urban streets, depicted by Edward Jump’s STEAMER DAY IN SAN FRANCISCO, (San Francisco, 1866).

Our cities have grown exponentially over the centuries. Looking at maps, the boundaries through the years expand outward, buildings grow upward, populations boom. But even in the 19th century, cities were disorienting places. While sanitized birds’-eye views tend to paint a rather orderly picture of tidy streets, the truth was often much messier, louder, and crowded. In the hubbub and whirl, you could lose yourself—in a good way, as no one knew you and you could engross yourself in the culture and forget yourself for a while. But the loss could be hard, too—a wrong turn, a stolen wallet, an overindulgence. The experience of getting lost, in its many forms, was entwined deeply with the experience of the city itself. And it makes you wonder, just a bit, in this age with a phone in our pocket whispering which way to turn, what we might lose when we can no longer get lost.

— Jayne Ptolemy

Assistant Curator of Manuscripts

Urban Panorama

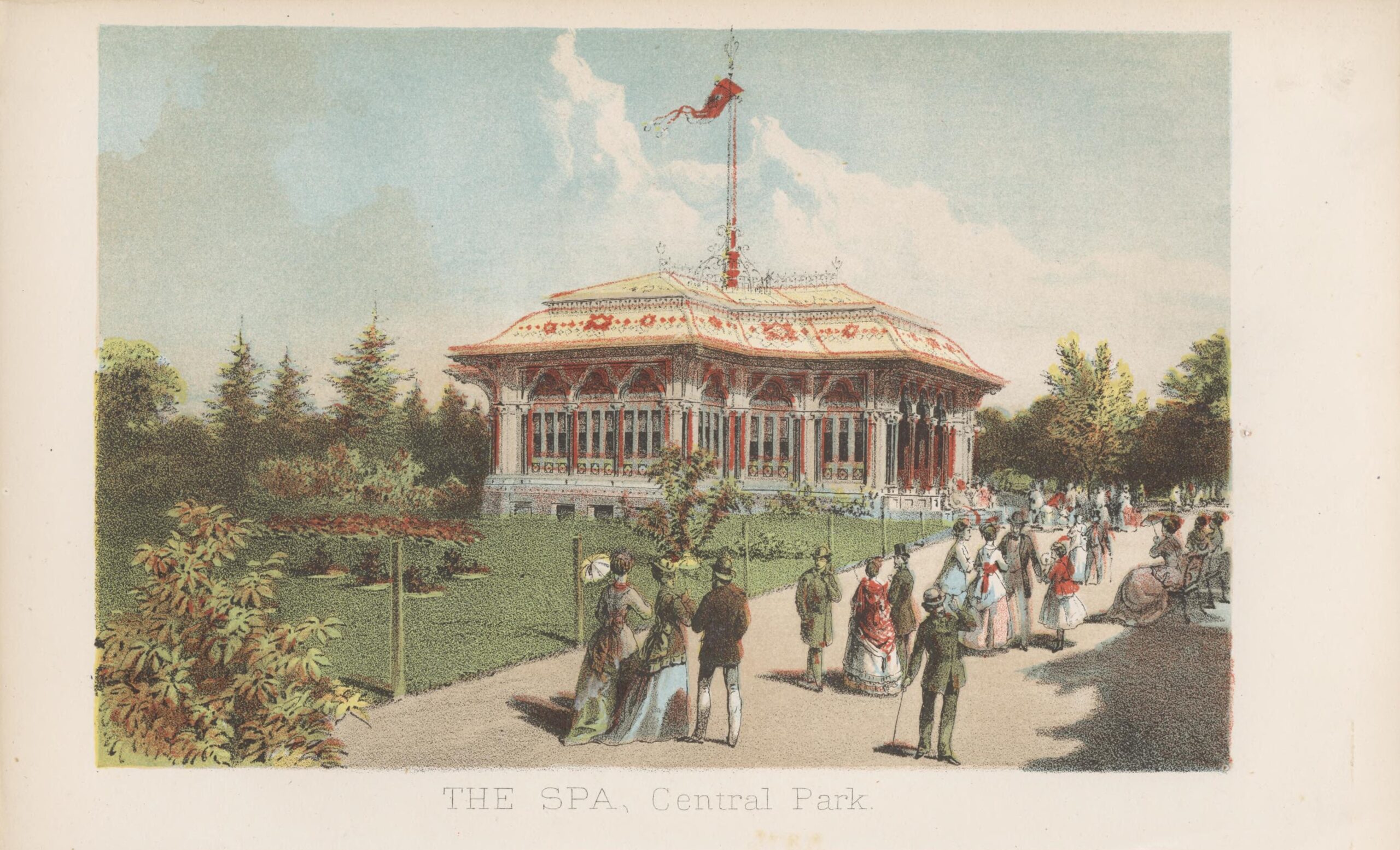

Artists have long striven to replicate visual perception and wrestled with the limits of various image production methods. One of the great historical challenges has been that paintings and photographs are static, while our actual perceptions unfold in time and space. Our eyes and heads are constantly moving from side to side and up and down. Scrolling painted panoramas—such as the Gettysburg Cyclorama (a cylindrical painting of the battle that opened to great acclaim in the 1880s) and table-top toys such as the zoetrope—were visual attempts to represent time and space in the 19th century. The first photographs that appeared before the public were dazzling in their detail. Early reactions to daguerreotypes described them as “frozen mirrors,” commenting on the amazingly fine qualities but also hinting at the inadequacy of the static and narrow field of view. An image from a box camera aimed in a single direction, however vivid in detail, does not represent the human experience of side to side vision as we move through space. Photographers were well aware of this—after all, Daguerre was also a painter of panoramas. Many took steps to better represent an active visual experience with their photographs, and the complexity and human activity of urban environments was a particularly tempting subject.

In the earliest attempts at wide-scale photographs, ambitious daguerreians framed multiple plates side by side to represent a wider field of vision. The 1848 panoramic view of Cincinnati by photographers Charles Fontayne and William S. Porter, now at the Cincinnati Public Library, took eight plates to capture a two-mile span of the riverfront. With the advent of paper photography, a series of prints could be pasted together to make a single sweeping panorama. These came close to replicating what we see as we shift our vision from side to side, but were still broken into segments. Achieving a uniform exposure and hiding the seams was a technical challenge for even the most skilled practitioner.

Flexible roll film began to replace glass and metal plates in the late 19th century and made it possible for a camera to have a curved film holder that maintained a constant focal distance for a very long piece of film. Add a lens that swivels from side to side and the true panoramic camera was born. The first mass-produced American panoramic camera, the Al-Vista, was introduced in 1898. Perhaps the most often used panoramic film camera was the Cirkut camera, patented in 1904. It used large format film, ranging in width from 5″ to 16″ and was capable of producing a 360-degree photograph measuring up to 20 feet long. For the most part, this equipment was used by professional photographers—the cameras were expensive and required unusual darkroom setups for printing the enormous negatives. But amazing things were now possible, such as seamless panoramic views of cities and photographs of very large groups of people.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers paused during the Detroit Labor Day parade of 1916. Each member held a staff with an electric bell on the top end, which appears to be wired to a controller on the lead vehicle. The bells were likely tuned to differing pitches, making this a walking musical instrument, suitable for a panoramic camera portrait. From the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, the majority portion donated by David B. Walters in honor of Harold L. Walters, UM class of 1947 and Marilyn S. Walters, UM class of 1950.

One of the obvious effects of panoramic photos in urban environments is that the straight lines of the man-made world appear curved and the perspective looks distorted in ways that don’t seem to match the way we understand our world. Although it looks wrong when viewed as a flat print, these images are in fact similar to the images received by our spherical eyes. What our brain “sees” is processed with other knowledge about the shapes and spaces around us so that we understand that the walls, although perceived in a spherical way, are in fact straight and vertical. The panoramic camera delivers just the image, stripped of any back-end mental processing, and so appears “wrong.”

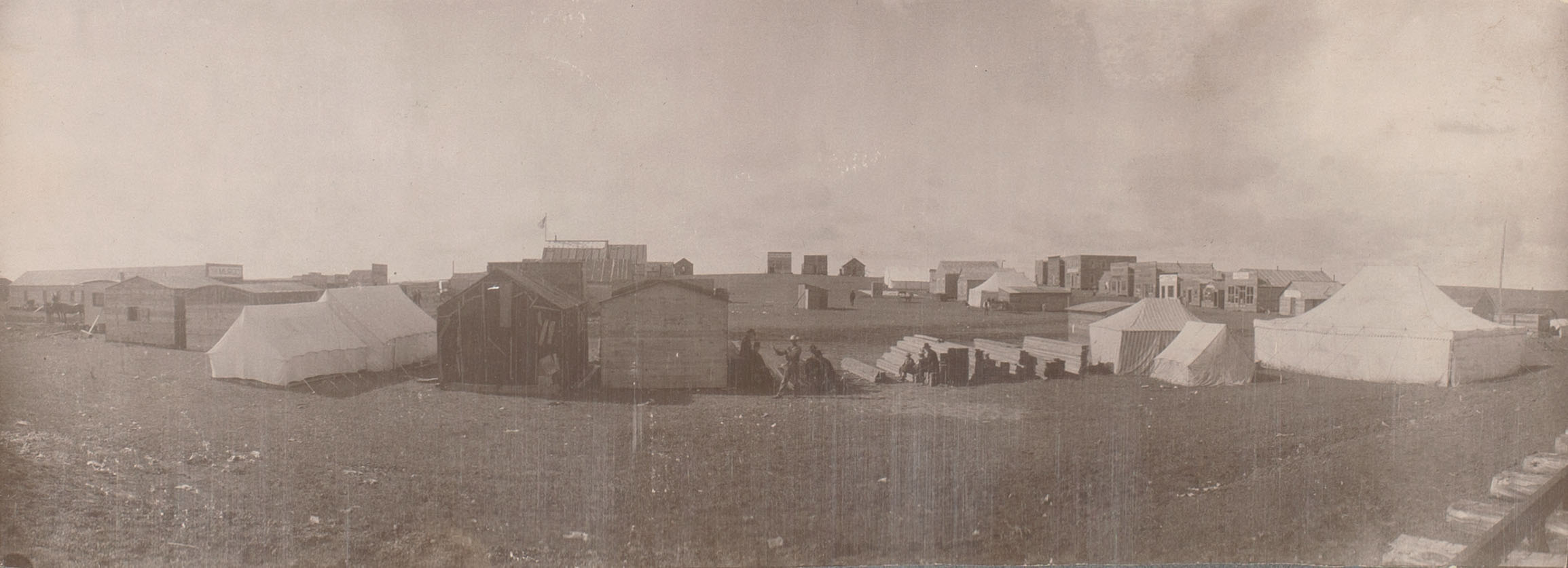

Among the scarce examples of amateur panoramic photography is this view of the emerging railroad town of Murdo, South Dakota, circa 1906. The town is named for Murdo McKenzie, a Texas rancher who drove masses of longhorn steers north to graze on the grasslands of Standing Rock Reservation of the Lakota and Dakota tribes. Other images from this album suggest that the photographer was the daughter of E.L. Morse of Chamberlain, South Dakota, who owned a dray and teamster business. The temporary shelters and recently unloaded stacks of lumber near the railroad tracks give the impression of a newly born town. The sweep of the panoramic camera expands the sense of endless grasslands. This may be the earliest image of the town of Murdo.

We are now in an era whereby we experience our surroundings through digital screens. Taking a panoramic photograph is now quite common as most digital cameras and phones provide this feature. Absent production costs, a digital camera can be a toy for visual experimentation. Digital panoramas of tall buildings taken vertically, and images made while walking or from a moving vehicle, present astonishingly original perspectives. Cities are subjects of such scale and complexity that to this day we are evolving new ways to view and understand them, and photographic panoramas continue to inform how we perceive and record our urban environment.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Materials

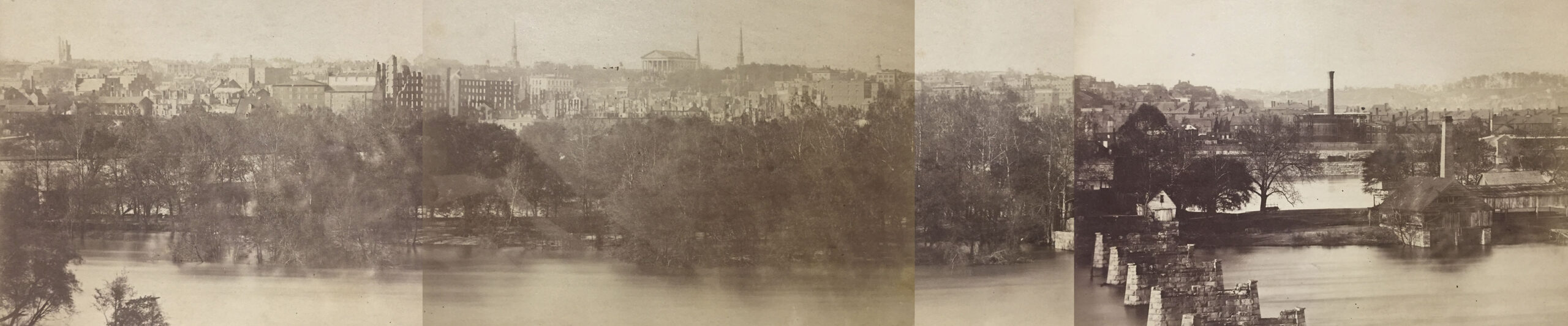

The devastation after the fall of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, in April of 1865 attracted photographers from across the country. This composite of nine eight-by-ten inch prints from glass plates by an unknown photographer is the earliest photographic panorama in the Clements collection. Numerous photographers took essentially the same photos from this same location within days of each other, making them nearly impossible to distinguish.

Encompassing 180 degrees, this viewof Campus Martius by The Hughes & Lyday Co. shows Detroit’s old City Hall and the Majestic Building along Woodward Avenue at Cadillac Square, probably taken in the early morning, using a camera with a pivoting lens. A slight dusting of snow covers the ground, except where streetcar traffic has swept it away. Most of the buildings pictured were demolished in the 1960s, but the 1867 Soldiers and Sailors Monument remains. Donated by Doug Aikenhead.

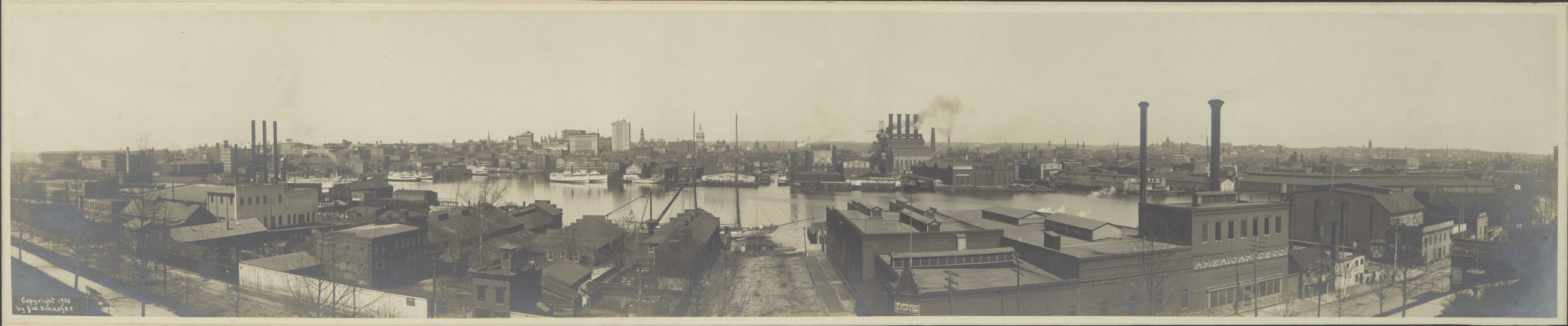

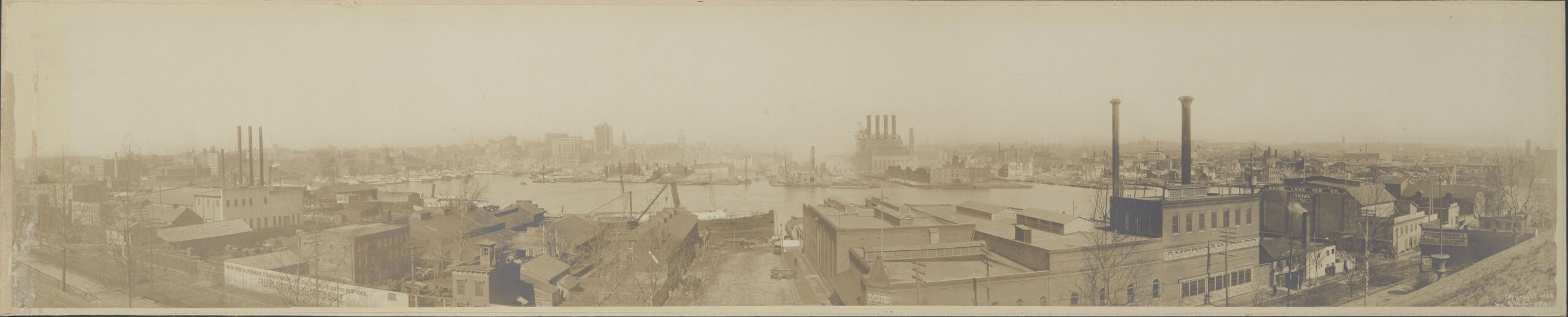

Among the very worst fires in American history was the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 that overwhelmed local firefighters and destroyed much of central Baltimore. Supporting equipment arriving from other cities was unable to be used due to inconsistent and varied hose sizes. This debacle led to federal laws standardizing fire hydrants and hoses. These two views were taken by G.W. Shaefer from the same location on Federal Hill overlooking the Inner Harbor before and shortly after the fire. Among the harbor-side industries on the near side is American Ice Company which supplied the fishing fleet with ice for preserving the fresh catch.

Thomas Sparrow was an Ohio photographer who specialized in panoramas of very large groups. A great deal of time went into the setup of this scene in front of the Saint John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Cleveland on May 2, 1915. The front steps were not large enough to hold the full congregation. The risers were assembled across the sidewalk in a measured arc so that the distance to the camera would be equal. Getting everyone in place and holding still for the time it took to make adjustments challenged the patience of all, no doubt. The result is a fantastic community portrait. Well done, Mr. Sparrow!

Developments — Summer/Fall 2022

Lately, I’ve been participating in the Clements crowdsourcing program “Picturing Michigan’s Past,” helping to categorize real photo postcards from the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. Through these images I see how humans were affecting the world around them. The project also sparks my curiosity and desire to find connections to the present day. Does that building still exist? Has the town grown? Do trains still travel along those tracks?

I enjoy knowing that through this endeavor we have created a digital online community (over 1,400 volunteers as I write this!) where people from around the world can interact with our collections and each other. This is one of many projects spearheaded by student interns over the years who have joined us to gain experience in the archives. Claire Danna, 2021–2023 Joyce Bonk Fellow, says this about working on the project: “As a student in the School of Information, I am interested in how technology helps us to present and transform data. It’s exciting to me to know that others will craft great stories and research from these materials.”

A selection of real-photo postcards from the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography on display in the Avenir Room at the Clements Library.

Not only have we seen volunteerism increase online, but financial support has also grown. This past year through several online crowdfunding campaigns and other initiatives, we have welcomed over 250 new donors to our community of supporters, the Clements Library Associates. This fall the Associates will celebrate 75 years of camaraderie in supporting the Clements Library. Formally established in 1947 during Howard Peckham’s directorship to raise acquisition funds, CLA members now support a wide range of programs at the Clements Library.

Whether we’re gathering in person or online, donations to the Randolph G. Adams Lecture Fund facilitate lively discussions through events. I am excited to continue hosting the Clements Bookworm, uniting people in a virtual space through Zoom. Tom Wagner joins in the live broadcast of the Bookworm every month and has this to say about the program: “As a non-historian, I continue to learn so much about our complicated American past from the Clements Bookworm. I enjoy the opportunity to ask questions and to see what others have to say in the chat. I am happy to sponsor episodes to keep the program going!”

Our visiting fellowship program continues to expand, as do our efforts to connect our fellows with Clements staff and other researchers. On Zoom, the staff gets to know fellows before they even step foot on campus. This affords the opportunity for researchers to elaborate upon their proposals and for staff to make suggestions for collection materials for them to use when they arrive. This summer we have moved our traditional daily in-person teatime with the fellows outside onto the south portico once a week. Daniel Couch, 2022 Reese Fellow in the Print Culture of the Americas, provided this feedback: “Everyone was super helpful. I love the teas. I think they’re great. The teatime was a perfect balance of not being too disruptive, but something to look forward to.”

Through philanthropy we continue to grow our fellowship offerings. Recently the community came together to establish funds in memory of two beloved university faculty members through the Julius S. Scott III Fellowship in Caribbean and Atlantic History and the John W. Shy Fellowship. In the coming months we will not only celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the CLA, but we will also recognize the centennial of the Clements Library. When William L. Clements graduated from the University of Michigan in 1882 with a degree in engineering, he set out to transform and urbanize physical landscapes by manufacturing steam shovels and cranes. As a U-M Regent he helped to revitalize central campus by working with Detroit-based architect Albert Kahn on many ambitious projects including our own building which opened in 1923.

As I reflect on the creative and innovative work that has been accomplished in the study of history over the last century, I doubt Mr. Clements could have imagined a campus-wide online catalog, digitization of materials, and crowd-sourced transcription and cataloging. I wonder what’s in store during the next 100 years? I am grateful that you have chosen to read this issue of The Quarto and invite you to join us in these celebrations and in shaping the future of this institution.

— Angela Oonk

Director of Development

Announcements — Summer/Fall 2022

Staff News

Lilian Varner has joined the Development and Communications Department as the new Marketing Coordinator. She will oversee social media, update the website, design printed materials, and assist in public outreach and events.

Isaac Burgdorf, an incoming student at the University of Michigan School of Information, has been with us since the winter as a part-time employee, providing invaluable assistance in many areas of the library—reception, reading room, and manuscripts.

During summer 2022 we hosted Reese Westerdale as part of the SummerWorks Internship program. Reese learned about different kinds of public outreach by working in both the Development and Communications Office and with the Librarian for Instruction and Engagement.

We welcome Aleksandra Kole as the George Hacker intern. Alex will physically incorporate a large new addition into the papers of James V. Mansfield, a prominent 19th-century medium and spirit postmaster. Alex is a junior at the University of Michigan, with a major in political science and a minor in philosophy.

In memory of Professor Emeritus John W. Shy

Professor Shy was the preeminent American authority on military aspects of the Revolutionary era. He taught at the University of Michigan from 1967 until 1995, and received the Distinguished Faculty Achievement Award in 1994. John was a regular researcher at the Clements Library as well as a longtime member of the Committee of Management and the

Clements Library Associates, and an avid participant in lectures and events. To honor his accomplishments and to encourage creative research at the Clements Library, friends and family have established the John W. Shy Fellowship and members of the War Studies Group have funded a John W. Shy Memorial Lecture expected to be held in March 2023.

John W. Shy with a revised 1990 edition of his publication, A People Numerous and Armed: Reflections on the Military Struggle for American Independence (New York, 1976), researched in part using the collections of the Clements Library.

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Mary Sue Coleman, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Kristin A. Cabral, Candace Dufek, William G. Earle, Charles R. Eisendrath, Derek J. Finley, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Troy E. Hollar, Martha S. Jones, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, James E. Laramy, Thomas C. Liebman, Richard C. Marsh, Janet Mueller, Drew Peslar, Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Peter Heydon, Chair Emeritus. Joanna Schoff.

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Tracy Payovich, Designer, [email protected]

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Sarah Hubbard, Okemos; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Mary Sue Coleman, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.