Embracing Online Possibilities

No. 53 (Winter/Spring 2021)

Table of Contents

- Embracing Online Possibilities

- Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

- Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

- Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

- Taking Fellowships Digital

- Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

- Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

- Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021

- Embracing Online Possibilities

- Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

- Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

- Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

- Taking Fellowships Digital

- Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

- Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

- Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021

Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

The concept that the human brain processes information differently when all our senses are engaged is fundamental to the mission of the Clements Library. Vintage leather bound books have a certain smell. Turning pages of old hand-made paper can make a crisp sound or a soft murmur. Books can be thick, thin, light or heavy. Historical documents have weight, texture, smells and sound that we respond to with more than our eyes alone. When in direct contact with rare materials, all of these elements stimulate our senses for a deep-dive immersion into the past that is impossible to replicate digitally. This has much to do with why we believe that the experience of working directly with original primary source materials brings out the best in scholars of history.

When studying historical photographs, there is a growing awareness that considerations of physicality contribute to meaning. It is easy to become so enraptured with the image itself that we can forget that it comes to us on a physical platform. A photo may be on paper, glass, metal, wood, ivory, perhaps in a protective case like a daguerreotype, or in a wooden frame for the wall. There is often a brittleness that commands cautious handling, and physical scale that can be surprising. Additionally, photographs are responsive to lighting conditions. The uniformity of computer screens can hide the fact that that photos can look different at different times of day, that daguerreotypes are highly reflective, but also carry deep contrasts.

The Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography contains a wide variety of physical formats: card-mounted paper photographic prints, unmounted glossy photos, small cartes de visite, large framed panoramic views, tintypes, stereoviews, and photo albums. Some of these photos invite intimate and up-close viewing, others broadcast from across the room.

Experiencing all of this in a rich sensory experience is what we had in mind when we posted internships funded by the Upton Family Foundation in the fall of 2018. The plan was to hire talented students to work directly with the Pohrt Collection materials to produce a traveling poster exhibit. We were delighted to bring on board Dr. Andrew Rutledge, whose qualifications exceeded our expectations. Andrew considered as a theme the dynamic but often troubling role that photography played in Native American history. In the 19th century, there was plenty of hostility between indigenous populations and the incoming settlers, soldiers, and photographers. However the Pohrt Collection also shows us hundreds of images that could not have been taken without cooperation from the Native American subjects. To what extent did these dynamics shape the Pohrt Collection materials? Are there 19th-century examples of Native Americans using photography for themselves?

Andrew researched the material, immersed himself in the history, and proposed a detailed exploration focused on the Great Lakes region and the Anishinaabe people. However, Andrew’s destiny lay elsewhere and he took an irresistible full-time position at the Bentley Library across town where he continues to do exemplary work for the university.

This set-back was also an opportunity to take stock of where we were and to re-set. We reposted the internship position and quickly found ourselves in a pleasant dilemma stemming from a remarkably talented pool of applicants. Fortunately, financial support allowed us to hire two interns, Lindsey Willow Smith and Veronica Cook Williamson.

Lindsey Willow Smith is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, majoring in History with a minor in Museum Studies. She is active within the Indigenous community on campus, serving as Chairman for the Native American Student Association. Lindsey is also researching the use of census data in describing Native populations with Arland Thornton and Linda Young-DeMarco at the Institute for Social Research at U-M.

Lindsey Willow Smith is a member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians and an undergraduate student at the University of Michigan, majoring in History with a minor in Museum Studies. She is active within the Indigenous community on campus, serving as Chairman for the Native American Student Association. Lindsey is also researching the use of census data in describing Native populations with Arland Thornton and Linda Young-DeMarco at the Institute for Social Research at U-M.

Veronica Cook Williamson is a graduate student in the department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and in the program of Museum Studies. Her primary research focuses on racial(izing) processes in media and other cultural representations of newcomers in Germany. She graduated with a BA in German Cultural Studies and Film and Media Studies from Dartmouth College in 2017. She has Irish, British, and Choctaw ancestry and is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation — chickasha saya.

Veronica Cook Williamson is a graduate student in the department of Germanic Languages and Literatures and in the program of Museum Studies. Her primary research focuses on racial(izing) processes in media and other cultural representations of newcomers in Germany. She graduated with a BA in German Cultural Studies and Film and Media Studies from Dartmouth College in 2017. She has Irish, British, and Choctaw ancestry and is a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation — chickasha saya.

The new team of Lindsey, Veronica, Graphics Cataloger Jakob Dopp, Reference Librarian Louis Miller, and myself met in the Library on March 3, full of ambition and anticipation. We did not know that this would be our only in-person meeting. On March 11 the University of Michigan closed its campus and remote work began, for what we thought would be a few weeks or months.

As the new reality took hold, it became apparent that the demand for online access and support for remote teaching superseded any of our plans for an “in real life” traveling exhibit. Should the internships continue? Fortunately, Jakob had completed item-level cataloging of the Pohrt Collection and Andrew, Jakob, and Louie had uploaded an extensive and detailed online finding aid for the collection. We had scans of most of the materials, enough that we could shift the project to the creation of an online exhibit. The internships could continue, and had the potential to create a timely and supportive resource.

We met regularly (on Zoom of course). Lindsey and Veronica proposed a rewrite that examined the issues of colonialism, Native sovereignty, self-identification, and cultural appropriation in the photographic representations—ideas that were challenging, but well-grounded in history and frequently downplayed.

The editing of the online exhibit, “No, Not Even for a Picture,” required the removal of some outstanding and important images. They include those pictured here and below. “Taking the Census at Standing Rock, Dakota.” D. F. Barry, 1885, 20 x 25 cm.

Detail, “Taking the Census at Standing Rock, Dakota.” F. Barry, 1885.

The man with the cane standing by the desk of the census enumerator is likely Lakota Chief Gall, one of Sitting Bull’s most trusted lieutenants at Little Big Horn, later a converted Christian who mediated assimilation. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) recorded the census annually during this time.

“L. Troop Mon. [S]Couts” O.S. Goff, 1890, 20 x 25 cm.

Nine unidentified Crow Indian scouts of L. Troop, 1st U.S. Cavalry Regiment, pose with their troop flag and a large American flag, possibly taken at Fort Maginnis, Montana. Many of the Native Americans enlisted in the United States military services were not citizens of the United States. Until the Indian Citizen Act of 1924, becoming a U.S. citizen often required formally leaving your tribe.

The themes and resources of the project were refined with invaluable input from Eric Hemenway, Director of Repatriation, Archives and Records for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and Arland Thornton, Professor of Sociology, Population Studies, and Survey Research at the University of Michigan, as well as from Richard Pohrt.

None of this work came easily. We had disagreements about interpretation and what was appropriate. The early versions had enough content for three exhibits. We were all sick of the isolation. Lindsey later commented that “as a Chippewa woman, the balancing of my views and experiences with those of the Clements was a chore.” She stated that “the inequity of emotional investment” was both wearisome and energizing. But as Veronica stated, “the photographs carried this project forward; they were the life force fighting back against video call malaise and quarantine fatigue.”

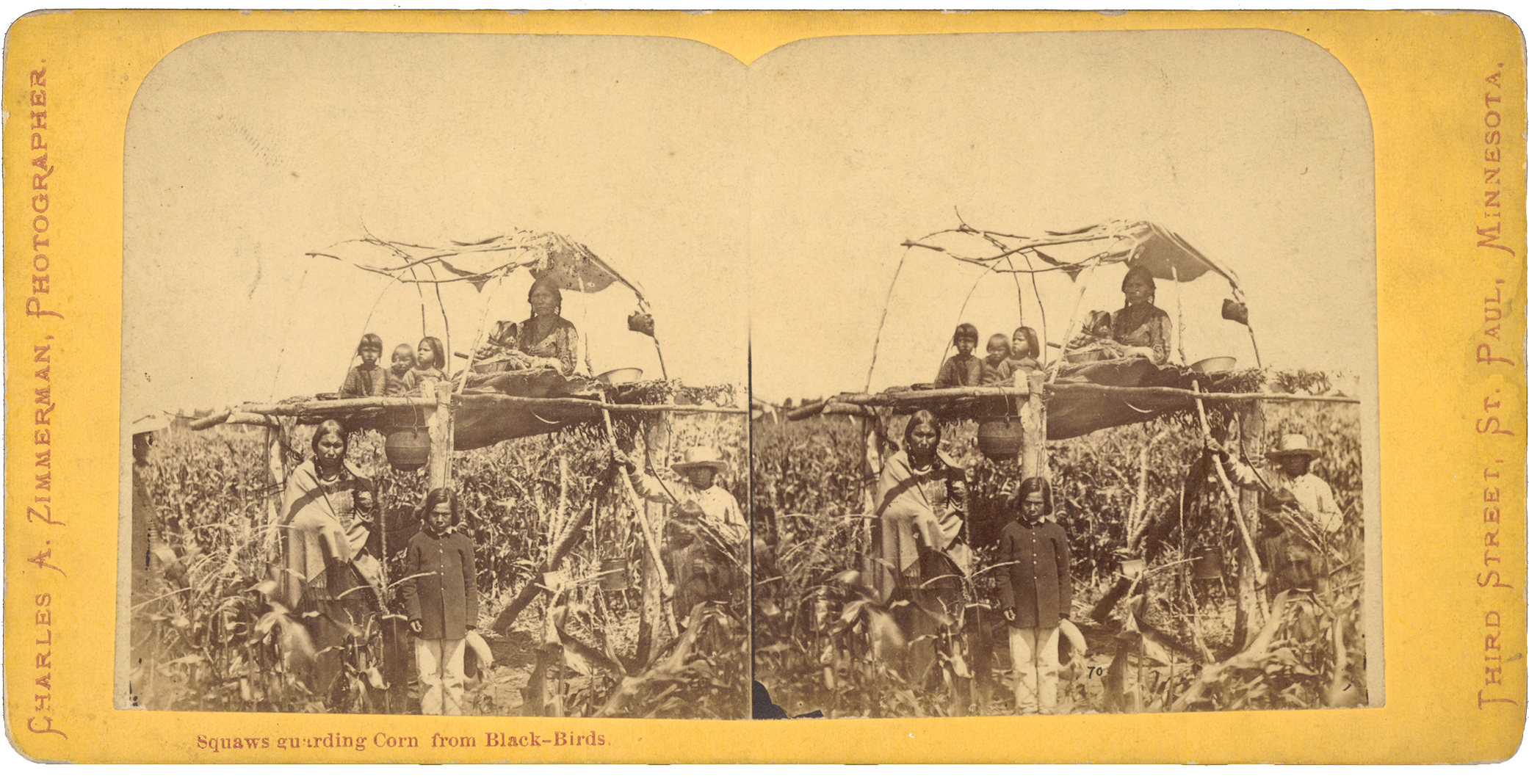

“Squaws Guarding Corn from Black-Birds” Adrian Ebell, ca. 1872, 8.5 x 18 cm.

Possibly taken on the very morning that the 1862 Dakota War uprisings began, this stereograph depicts an unidentified Dakota woman and four children sitting on an elevated platform standing watch over crops. This 1872 print from the 1862 negative would have been produced sometime after Charles Zimmerman took over the Whitney Gallery.

Later in the summer, University policies allowed access to the Clements building and the collection. After many months of remote work, Lindsey and Veronica had their first opportunity to view the actual photos at the Library. The power of this materiality is discussed eloquently in Lindsey and Veronica’s blog post for the Clements Library Chronicles.

I am very proud of this project. I am particularly proud that issues were discussed and decided within the team, that the curation and interpretive concept were led by Lindsey and Veronica, and that their voices came to the fore in the final product. In spite of being thrust together as strangers forced to be partners, employed by an institution that neither knew, using unfamiliar work and communication methods, with a pandemic just outside the door, Lindsey and Veronica’s talents and visions meshed. They create a unified, thoughtful, and challenging look at photography and Native American history that will have lasting value as well as serving the immediate need to support remote education. The online exhibit, “No, Not Even For a Picture,” is a remarkable accomplishment under any circumstances. Given what the project team faced, it is all the more so. It is only one of many projects that are waiting to emerge from the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Material

- Embracing Online Possibilities

- Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

- Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

- Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

- Taking Fellowships Digital

- Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

- Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

- Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021