Embracing Online Possibilities

No. 53 (Winter/Spring 2021)

Table of Contents

- Embracing Online Possibilities

- Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

- Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

- Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

- Taking Fellowships Digital

- Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

- Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

- Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021

- Embracing Online Possibilities

- Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

- Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

- Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

- Taking Fellowships Digital

- Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

- Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

- Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021

Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

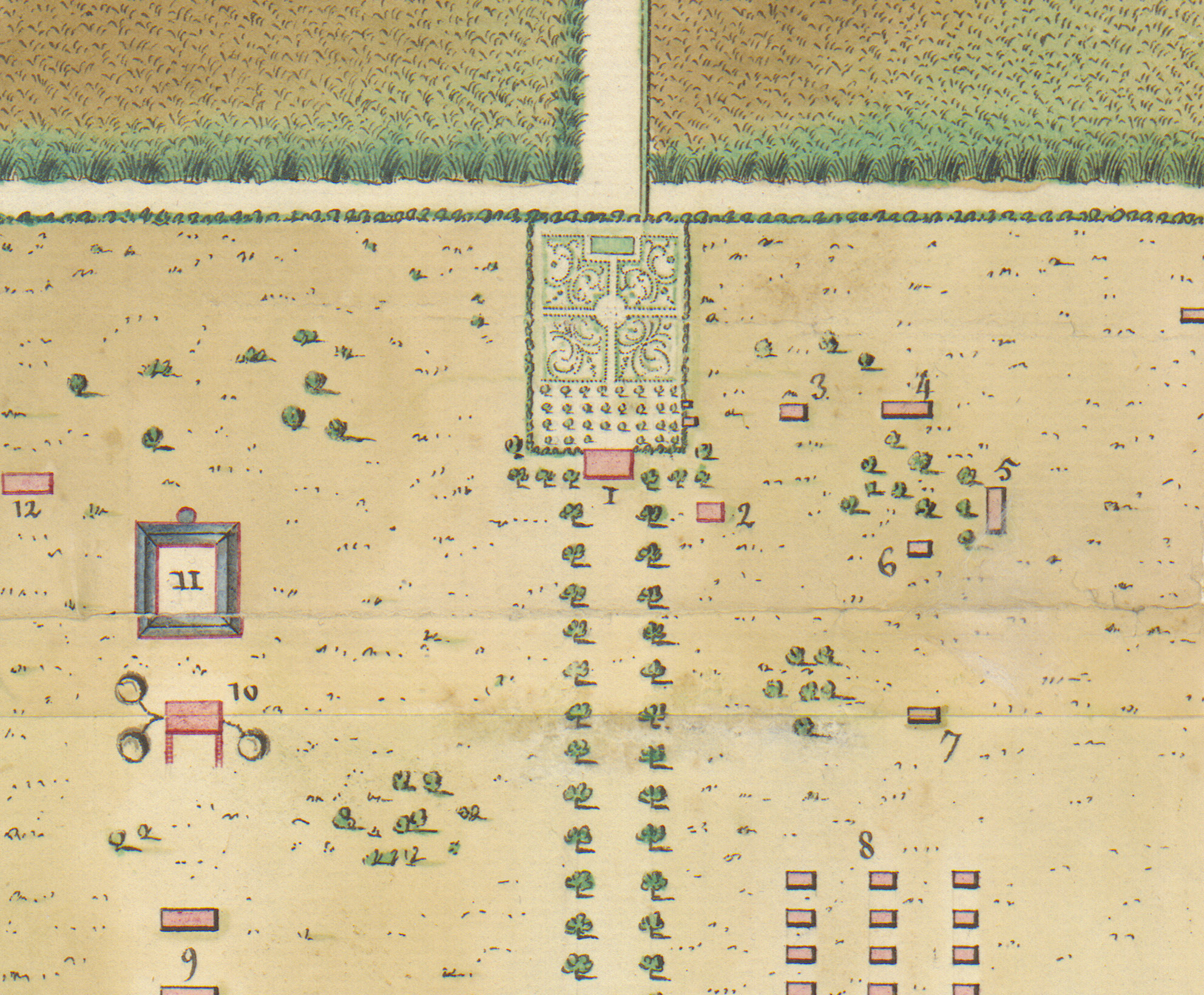

The plan of Jean-Baptiste de La Porte-Lalanne’s Haiti plantation is the sort of document you have to walk around. Produced in 1753, its features demonstrate the organization and efficiency of 18th-century Atlantic trade, and the conditions of those enslaved at its expense. For teachers and students, the document exemplifies the texts and subtexts that can be found in primary sources and historical research.

Leaning in to view the plan, students might notice the vast uniformity of the sugar fields, the intricacy of the main garden, or the blockish imprecision of the slave quarters. Walking around the document, other names hug the borders of La Porte-Lalanne’s land, signs of the many other plantations that extracted lives and commodities at such scale. Perhaps even touching the paper, one might ponder on the many folds that have disrupted its surface, remnants of its past storage and transportation.

We will never see this plantation, so we must cling to every clue we can find. Yet in 2020, in the midst of a pandemic, we have been distanced further. Our challenges as historians and teachers are not only temporal, but also material. In the absence of in-person interactions, archives and their documents must be met anew.

This was the challenge when arranging a collaborative session between the William L. Clements Library and the undergraduate students of Michigan’s early American history survey course, investigating the documents and history of the Atlantic slave trade. In past years, students met curators and documents in person, discussing and exploring sources in the Clements’ atmospheric reading room. As an instructor, those visits offered the opportunity to take my students somewhere new, outside of the classroom and beyond the realm of PDFs and laptop screens.

With the shift to online learning, these encounters had to be reimagined.

A cardinal rule for researching in person at the Clements Library is never to make marks on historical documents. The online setting allows students to highlight and comment on this passage from the Leyland Company records of a slave trade voyage.

Working with Jayne Ptolemy and Clayton Lewis from the Clements staff, we faced the challenge of bringing students to the Clements over Zoom. This meant factoring in the dynamics and difficulties of the digital environment: the default muting of microphones; the distractions of computers and home life; the dreaded lag and spotty wifi.

Our planning focused on maximizing discussion and minimizing the potentially overwhelming array of classroom technologies. We decided to focus on in-depth preparation and the discussion of just two sources: Jean-Baptiste de La Porte-Lalanne’s plantation and an account book of the Thomas Leyland Company, recording a single slave voyage from Liverpool to Angola, and finally Barbados.

With the variety of technologies on offer, we discovered new opportunities for student engagement and discussion. In advance of the session, students were asked to read through the Thomas Leyland account book. Using Perusall, a digital reading tool, students could discuss the source online, posing questions and responding to each other’s comments.

This meant that we were provided with an array of questions and overlapping interests that might otherwise have been missed with individual preparation. Students asked about the goods transported on the ship, and the various systems of measurement. They conversed about the various professional roles on board, and the fact that seamen could be paid in human beings as well as currency. They expressed their shock at the scale of this journey and its place in the trade as a whole: one of 45 such voyages arranged by Thomas Leyland, and a fraction of over 36,000 in the trade overall. Two hundred sixty-six anonymous lives, in a trade that displaced millions.

Armed with these questions and comments, the Clements curators could present the primary sources in a personalized way for each student. Over Zoom, we could explore students’ reactions to the document, without simply calling upon the most vocal. Digital tools, at least on this occasion, democratized involvement and encouraged broad participation. It was no surprise that Perusall was requested by students in subsequent weeks and will continue to be a valuable tool, even after the return to in-person teaching.

Using Perusall analytics, an online teaching tool, staff can use data—in this case, how long students spent looking at individual pages of the Thomas Leyland Company Account Books—to better understand student engagement with an eye toward improving remote instruction.

This detail from “Plan de l’Habitation de Monsieur de La Port-Lalanne” shows the main plantation house, formal gardens, and a hint of the surrounding sugar cane fields. This small detail shows less than 10% of the overall plan.

Next up was the plan of La Porte-Lalanne’s plantation. This time, without any prior preparation, we directed the students to its place on the Clements website and asked for their first impressions. With significant squinting and zooming in, the plan’s details began to come to light. Given the document’s size, and the restrictions of their computer screens, students were forced to slowly tour the plantation. They had to scroll methodically through its details, perambulating rather than surveying the document as a whole.

With this unique focus, students noticed the smallest features. The lack of trees and shade by the slave quarters, and their distance from almost every other building. The individual sugar canes, indicating the decorative, as well as practical purposes of the plan.

It is impossible to replace in-person encounters with documents, yet digital tools and discussion revealed elements that might otherwise have been missed by the naked eye. And thanks to the expertise of the Clements curators, each component observed by students could be expanded to the broader history of the slave trade and Atlantic history.

While I am undoubtedly excited by the prospect of bringing students back to the Clements Library, it is important that we do not forget the lessons learned in digital teaching. We must continue to consider the circumstances of our students, beyond computer and wifi access. We must work to incorporate ways of learning and participating that do not prioritize certain voices. We must reflect on new ways of viewing and discussing historical documents. We must lean in and take a closer look.

—Alexander Clayton is a Ph.D Student and Graduate Instructor in the University of Michigan History Department. His research and teaching focus on Atlantic History and the History of Science.

- Embracing Online Possibilities

- Primary Sources through a Digital Lens: Reflections on Remote Teaching with the Clements Collections

- Pandemic Propels Digitization Progress

- Enhancing Digitized Collections: The Transcription Project

- Taking Fellowships Digital

- Pohrt Exhibit Pivots Online

- Developments – Winter/Spring 2021

- Announcements – Winter/Spring 2021