Table of Contents

- Manifestations of Faith

- “Don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology”: Horace, Ode I. 11

- “This I will seale with my blood”: The Execution of William Leddra

- These are the Great Instruments of Providence

- Recent Acquisitions — Winter-Spring 2022

- Developments — Winter/Spring 2022

- Announcements — Winter/Spring 2022

- Manifestations of Faith

- “Don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology”: Horace, Ode I. 11

- “This I will seale with my blood”: The Execution of William Leddra

- These are the Great Instruments of Providence

- Recent Acquisitions — Winter-Spring 2022

- Developments — Winter/Spring 2022

- Announcements — Winter/Spring 2022

“Don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology”: Horace, Ode I. 11

The Second Great Awakening swept the country in the 1830s and 1840s, reviving established churches and spawning fringe sects. Millennialism and the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ were some of the main motives for religious conversion. The question of exactly when was answered by Baptist minister, evangelical apocalyptic theologian, and farmer William Miller (1782-1849).

Miller’s study of the books of the Bible, particularly Daniel and the Book of Revelation, led him to believe that “prophetical scripture is very much of it communicated to us by figures and highly and richly adorned metaphors.” He believed his analysis of the chronology of events in the Old and New Testaments could determine the date of the Second Coming of Christ and the “cleansing of the sanctuary” prophesied by Daniel. Miller based his calculation on the number 2300 which he found in Daniel 8:14: “Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed” (King James Bible). Miller calculated that “the vision of Daniel begins 457 years before Christ; take from 2300, leaves 1843, after Christ, when the vision must be finished.” Miller presumed that biblical days meant years. From this equation, as well as other numerological combinations from the Bible that yielded 1843, Miller concluded that the Second Coming must occur between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844.

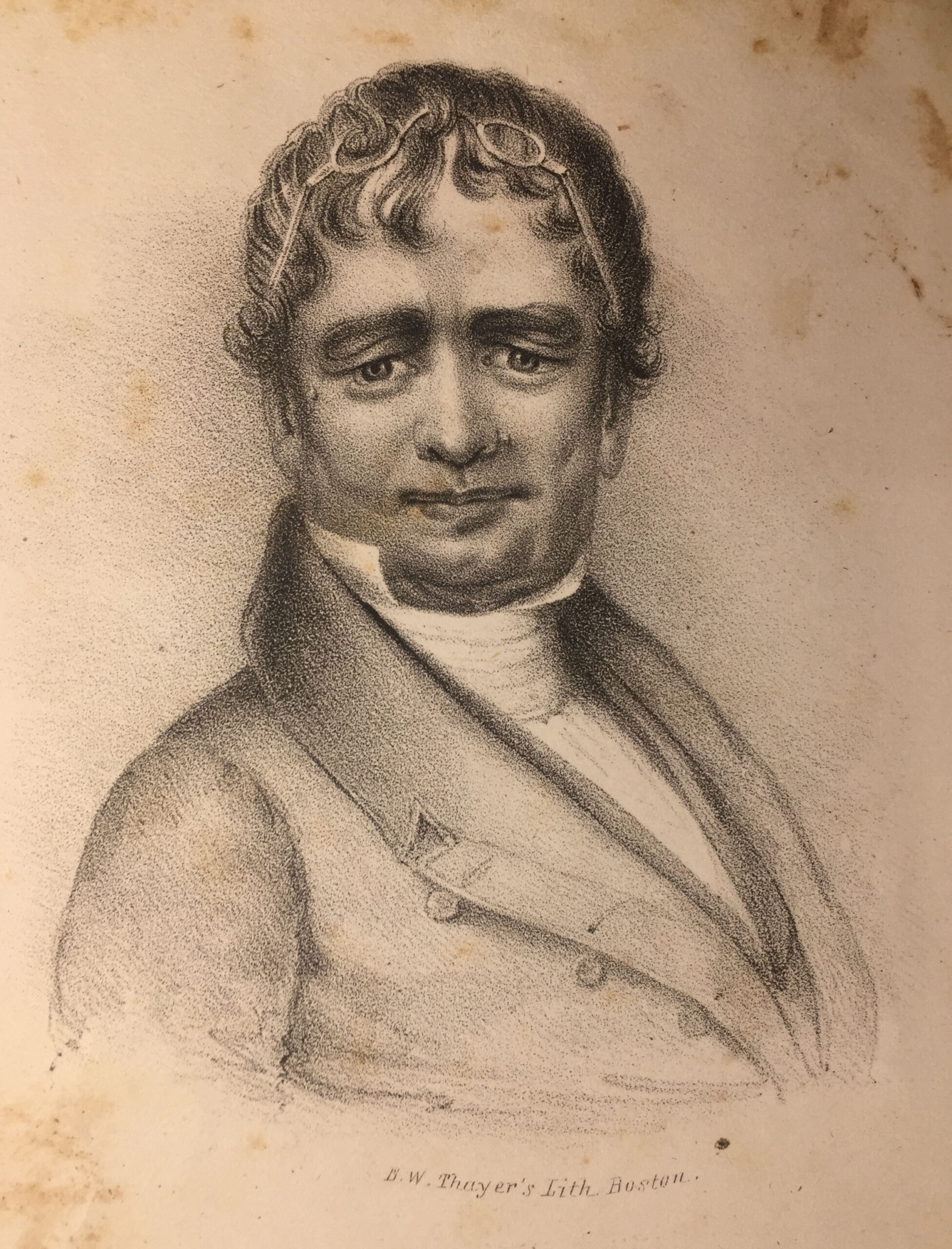

Wm. Miller. [Boston, 1841]. Lithograph by Benjamin Thayer (1814-1875), from a painting by William M. Prior (1806-1873).

Riding the wave of the Second Great Awakening, Miller gathered a following with fiery sermons on this topic. He promoted his vision to credulous audiences in churches and meeting houses across the northeast United States.

By 1839, Miller had crossed paths with Boston lithographer, publisher, and social reformer Joshua Vaughan Himes (1805–1895). Himes sat in on several of Miller’s sermons and soon became both a follower and promoter. Himes published the sermons and Millerite newspapers Signs of the Times (Boston) and Midnight Cry (New York), organized Miller’s speaking tours, and boosted Miller’s following to a peak of perhaps 50,000.

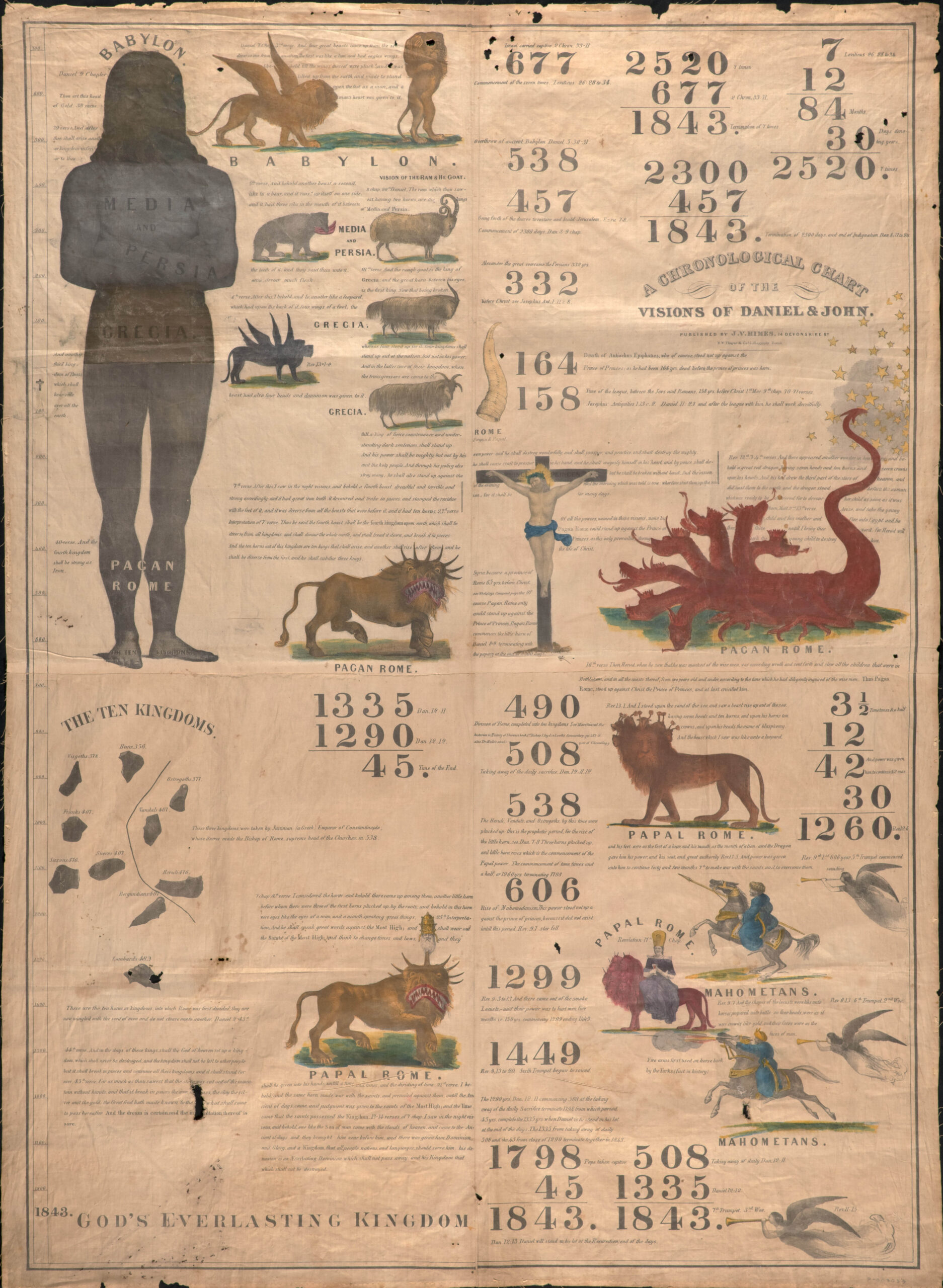

Miller’s references to the books of Daniel and Revelation and the calculations essential to Millerite belief were complicated and hard to follow. Visual aids would help explain the premise and hold attention. Himes worked with preachers Charles Fitch and Apollos Hale to design a prophetic chart that would summarize and illustrate Miller’s vision. Himes’ 1842 broadside print, Chronological Chart of the Visions of Daniel & John was produced from four lithography stones on a large 60 by 45 inch piece of fabric that could be easily folded, transported, and hung at the front of a lecture hall or from the branch of a tree outdoors.

Simultaneous with the Second Great Awakening were rapid advances in visual culture through printing technology and growing literacy. Print media became cheaper, faster, and more persuasive with sophisticated combinations of text and image. Social movements such as abolitionism leveraged this with provocative broadside prints that compelled an emotional response, such as the heart-wrenching kneeling slave image or the dramatic diagrams of slave ship interiors.

Religious pictures are often persuasive through emotional connections of a different sort. Iconic saints and holy family depictions can be deeply reassuring in their humanness. Last Judgment images threaten unending pain. The images associated with Himes’ Millerite banners are altogether something else.

A Chronological Chart of the Visions of Daniel and John ([Boston]: J. V. Himes, [1843]). Printed on fabric by Benjamin Thayer. A timeline from circa 700 to 1843 runs vertically along the left, with images of mythical beasts from Revelation and calculations based on biblical numerology. Later editions recalculated the final date to 1844, 1850, and 1853, by which time interest had waned.

Joshua Himes’ Millerite broadside combines images, numbers, texts, and timelines to generate a powerful, mysterious manifestation. Representing history from the year 700 to 1843 it addresses the unknowable future with the logic of a mathematical equation and the certainty of advancing measurable time, coupled with strange and compelling mythological metaphorical creatures, biblical figures, and monarchs from pre-history. All this, combined with the impossibility of disproving an event that has not yet occurred, made a powerful, if not fully understandable case.

As Millerites grew in numbers, their opponents grew as well, with refutations such as Abel Tompkins’ self-published Miller Overthrown: Or The False Prophet Confounded. By a Cosmopolite (Boston, 1840). “This is the day of strange things. We have phrenology, animal magnetism, sleeping preaching, political crisises [sic], and the end of the world. . . . science is always followed by her shadow, which some mistake for the substance. The same may be said of religion. Many deceivers have crept under the sacred mantle of religion, and William Miller is one of them.” A defensive Miller struck back. “My opponents have been in the habit too of spreading false reports, in order to destroy the influence of what they cannot refute. They have published my death in public papers . . . that I had altered my calculation of prophetic time a hundred years. . . . that I would not gamble away my little home. . . . that I built a stone-wall instead of a rail-fence on my farm.” Rationalists, Deists and Universalists received Miller’s scorn “In every place that this subject has been judiciously preached, [they] have been made by the power of the Spirit to see and feel their danger. . . . I beg of you to lay aside your prejudice, examine this subject candidly and carefully for yourselves. Your belief or unbelief will not effect the truth.”

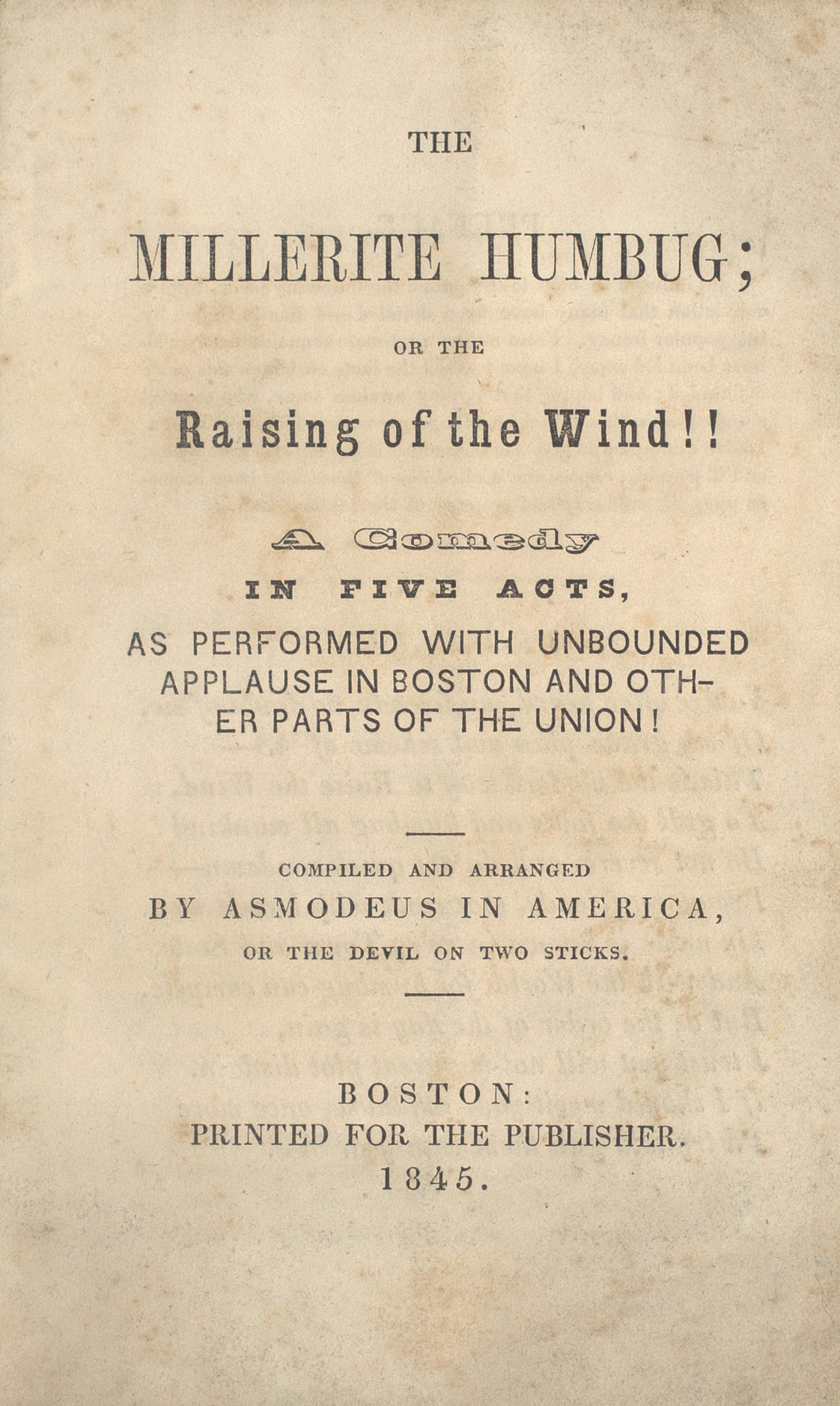

Miller’s inconstant predictions provided grist for the satirist’s mill, as in this “Comedy in five acts,” the Millerite Humbug; or the Raising of the Wind!! (Boston, 1845). The pseudonymous author, Asmodeus, was “induced to offer to the public the following piece, from a conviction that many have been deluded and finally ruined by the popular frenzy . . . and if possible, expose the wickedness of those who have imposed upon the credulity and property of their fellow man.”

Miller’s deadline for the apocalypse (shifting several times as it passed) came and went, marking not The End, but the beginning of the phase known now as The Great Disappointment. The disappointment was especially profound for those who had sold their possessions, down to their shoes, in expectation of never walking on Earth again.

Scorn, criticism, and outright violence erupted as Millerite congregations turned against themselves. Many theories came forth as to what happened—the date should have been based on the Karaite Jewish calendar and not the Rabbinic calendar; the appearance of Christ was invisible to mortals; the predicted “cleansing of the sanctuary” was occurring in heaven, not on Earth; and many others. Millerite sects gathered around several main theories and carried on, but in understandably smaller numbers. Miller’s prophecies continue in varying degrees in the Adventist movement and in the theology of the Baháʼí Faith.

The absurdity of setting an exact date for The End is easy to ridicule, but at the core it was driven by ordinary people dealing with legitimate fears during times of stress and social upheaval. The decades of the 1830s and 1840s saw massive societal changes in urbanization, industrialization, financial instability, enslavement, immigration, citizenship, and other social issues in addition to emerging religious movements such as Mormonism. It is no wonder there were questions about destiny and finality. Who wouldn’t want to know when it all will end? Those with answers could draw a crowd. Miller and Himes, with mysterious mathematical formulas and dazzling diagrams, packed the house.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Material

Ode I. 11 Horace

Translated by Patrick Whalen

Do not wonder, better not to know, what end the gods hold in mind.

Whatever will become of me and you,

Leuconoe, don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology.

What will be is what we will endure:

Either more winters will follow, or Jupiter says this

Which eats away the cliffs along the Tyrrhenian Sea

Is the final winter. Be wise; strain your wine, trim your long hopes

To a point. Even as we speak envious eternity turns fugitive.

Seize the day. Believe in tomorrow but barely.

- Manifestations of Faith

- “Don’t tempt the Babylonian numerology”: Horace, Ode I. 11

- “This I will seale with my blood”: The Execution of William Leddra

- These are the Great Instruments of Providence

- Recent Acquisitions — Winter-Spring 2022

- Developments — Winter/Spring 2022

- Announcements — Winter/Spring 2022