TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

One is the Loneliest Number

Paul J. Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director

William L. Clements Library

“Tiny Things” may seem like an unusual theme for a Clements Library Quarto. Like most of our peer institutions, we often tend to focus on big things: the largest collection of this, the deepest holdings of that, the longest shelves, the most titles by Author X. We love our Audubon folios. We celebrate the acquisition of flashy, famous items, which are also often large. Librarians and scholars alike are drawn to materials from the past that had an impact—books that were the biggest sellers, that were read by the most important people. And I’m as guilty of this as anyone. A book that was published that nobody read is kind of like the tree that falls in the forest with nobody around to hear it.

The three-volume publication, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, (Philadelphia, 1845-1848) resulted from a collaboration among John James Audubon (1785–1851), John Woodhouse Audubon (1812–1862), Victor Gifford Audubon (1809–1860), naturalist John Bachman (1790–1874), and lithographer William Hitchcock (ca. 1823–ca. 1880); at 72 cm, this “Imperial folio” edition was printed by J.T. Bowen.

Even the way we store our collections privileges big and weighty artifacts. Our biggest books—which we call folios—have their own shelves. Meanwhile, our smallest printed books are batched together in acid-free boxes in the “Pamphlets” and “Juveniles” section of the stacks. This all makes perfectly good sense, of course. Given our interest in using space as efficiently as possible, it’s entirely logical to store the largest books on the tallest shelves. And from the perspective of preserving our fragile collection items, storing small children’s books and paper-covered pamphlets in boxes protects them from the damage they would suffer if they were on open shelves with the rest of the collection.

This issue of The Quarto asks you to pick up a magnifying glass and think small. The pieces in this issue focus on small books, small maps, small pictures, or books about small things. Miniature books and prints are often wonderful examples of the art and craft of bookmaking and illustration. The challenge of creating a tiny version of a book that still functions as a book is a test of the skill of printers and binders alike, and many collectors are drawn to these items for just this reason.

But what if we come at the question of tiny from a different direction? Instead of thinking about small things, what if we thought about small audiences? My interest in books from the past grew out of an interest in readers from the past, which is to say that I was interested in the audience. When I read an 18th- or 19th-century American book, I often think more about who would have read it and how than I do about who wrote it or who printed it. So in thinking about “tiny things” for this issue, I was led to think about readers rather than books themselves.

Of course, how books are produced has a direct bearing on how many people read them. In his book Popular History and the Literary Marketplace, 1840–1920 (Amherst, Mass., 2008), Gregory Pfitzer offers what is my favorite definition of “popular” literature. He writes that “popular” printed items are things for which “every aspect . . . was designed to increase sales.” Which is to say that a “popular” book was one that was written, printed, bound, and sold in ways that were very specifically intended to sell more copies. Now, you might reasonably ask, “Doesn’t everybody who prints books want to sell as many copies as they can?” To which I would reply, “Does Rolls Royce want to sell as many cars as they can, or do they want to sell a small number of cars to very specific people?” Some books are Rolls Royces, deluxe items meant to generate a large return from each single copy sold to an elite market. Other books are Honda Civics, meant to generate small returns from a huge number of copies sold to just about anybody. And if you browsed the shelves of the Clements Library’s stacks, you’d be able to pretty easily tell the Rolls Royces from the Hondas, just as you would in a parking lot.

What I’m really interested in are things that look like Honda Civics but were made for a Rolls Royce-sized market—that is, things that were cheaply made but intended for a tiny audience. I’m both fascinated and delighted by the amount of labor that people in the past put forth to create something that just a handful of people, or maybe only one person, would ever see, using processes that were developed for mass circulation.

Corn husks are now used in boutique paper products, but the process for creating the fragile husking party invitation in 1885 would have been time-consuming and labor-intensive.

One example of this that I especially love is a recently acquired invitation to a “Husking Party” in West Springfield (it’s not clear which one—there are five “West Springfields” in the United States) in September 1885. The invitation was printed on the most appropriate and the most ephemeral possible material: a corn husk. Maybe more than one person saw this invitation, but given that it survived, it almost certainly wasn’t passed around. Yet William Thomas had to go to the trouble to collect enough corn husks to generate a good crowd for his party. He had to trim them to size and flatten them so that they’d take ink. And he had to set type—using four different typefaces—that would actually print on the husk. All this work, for something that was intended for only one person to see.

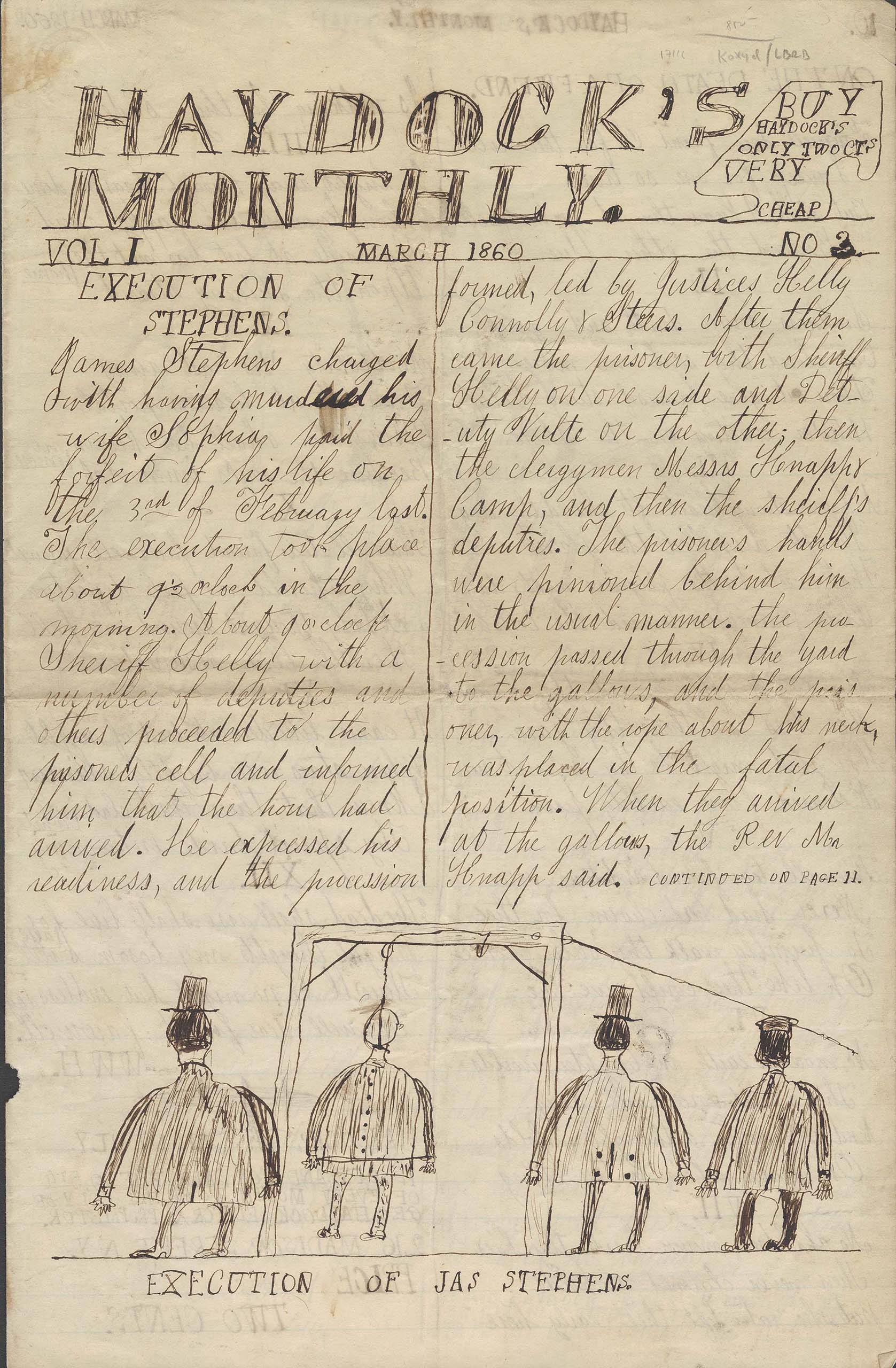

Many manuscript items, such as letters, were only intended for an audience of one, and the fact that they’ve wound up in a place like the Clements might surprise their authors, since generations of scholars are now able to read their private thoughts. But some manuscript forms were created to mimic forms of print that were intended for wider circulation, although they still likely only reached a few individuals. The Clements holds several examples of manuscript newspapers—hand-written versions typically created by children that mimic the appearance of printed periodicals. Some focused solely on news that was relevant to the author’s household, such as what the cat had been up to. Others, like George Haydock’s “Haydock’s Monthly,” “published” in New York City in March 1860, presented a version of a real news story (about the execution of a man convicted of murdering his wife), complete with an illustration of the gallows. The subscription information included on page 10 of the issue lets the small readership know who to pay their two cents for the next issue. The time and effort that George Haydock put into hand-writing copies of his newspaper (who knows how many?) very likely “did not come close to justifying the per issue price, given that his audience likely numbered in the single digits.

Reading items like these, that were produced for a tiny number of readers, can feel like eavesdropping on a conversation. William Thomas’ party invitation was created to be circulated, but the copy at the Clements was almost certainly intended for only one person. And George Haydock’s newspaper was produced for sale—or at least it replicated the subscription information from the newspapers it imitated. But in neither case did the creators think that the audience for their works would include readers in a library in Michigan 150 years in the future.

The James Stephens case, featured in “Haydock’s Monthly,” was notorious in its time, involving the poisoning of Stephens’ wife, the assault of her niece, a revenge shooting by the victim’s nephew, and Stephens’ escape and re-capture—all elements sure to appeal to an active and enterprising lad. “Haydock’s Monthly” is part of the James V. Medler Crime Collection.

When I think about scale—about smallness—in the Clements collections, it is these moments of privacy that come to mind first, often because they are the most moving to me. In early August a new daguerreotype arrived at the library that took my breath away, precisely because the moment it captured was so tiny, so private. A white child of perhaps two or three years of age posed for a photograph. But instead of the “hidden mother” method, where a child’s mother would hold a child still for a photographer while concealed under a covering, this child is being comforted in a more visible, yet more private way. From outside of the picture’s frame on the child’s right, a hand of an otherwise unseen African American person gently holds the child’s hand in reassurance. We don’t know who the child is, nor do we know where the daguerreotype was made. We also don’t know who was offering their hand to comfort that child. Was it a hired nanny? A person enslaved by the child’s family? An employee of the photographer? We’ll likely never know. But that extended calming hand—a moment so brief that if you blink you’ll miss it—is the kind of small, quiet moment that close attention to the items in the Clements collections can reveal. Sometimes, tiny things mean the most.