THE CENTENNIAL ISSUE

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

Table of Contents

- Evolution of an Archive

- “Who Knows but a Woman May One Day Preside Here”

- The Threads That Bind Us

- Illuminating Revolutionary War America

- Elegant to Eccentric

- Mysteries of the Deep

- Mapping Research Trends in the Collections

- Recent Acquisitions

- Philanthropy Builds the Archive and is Recorded There, Too

- Announcements — Winter/Spring 2023

- Evolution of an Archive

- “Who Knows but a Woman May One Day Preside Here”

- The Threads That Bind Us

- Illuminating Revolutionary War America

- Elegant to Eccentric

- Mysteries of the Deep

- Mapping Research Trends in the Collections

- Recent Acquisitions

- Philanthropy Builds the Archive and is Recorded There, Too

- Announcements — Winter/Spring 2023

Mapping Research Trends in the Collections

Maps have always been an integral part of the library’s collections, starting with Mr. Clements’ early acquisitions prior to his gift to the University. Because maps reflect time, place, and author’s intent, some research themes can prove more elusive for older maps—for instance, the representation of two important communities on maps: Native Americans and enslaved Africans. While Native Americans held priority of geographic place and African Americans arrived via forced immigration, both groups endured forms of displacement within the North American space.

Detail from Guillaume Delisle (1675–1726), Carte du Canada (Paris, 1703). Delisle, a geographer in Paris, compiled this map from many missionary reports and other first hand accounts from the region, populating the area around the Great Lakes with Native American place names and identifiable groups.

The location of Native American groups in North America challenged mapmakers, given the seasonal mobility and fluctuating numbers of many indigenous groups. Yet their very mobility meant that indigenous modes of mapmaking and representation had much to offer early French explorers and missionaries, who often recorded these verbal and sometimes performative maps, although physical maps were rarely replicated. Nonetheless indigenous presence, indicated by the appearance of various group names, are a staple feature of French maps of North America from the 17th century onwards.

Some British mapmakers who carried out ground surveys in colonial regions similarly included Native American groups, territories, and aboriginal claims. A focused British interest in the location of Native American groups is displayed in this manuscript map. “A Map of the Indian Nations” was probably prepared for the British military administration at the time of the cession of the transAppalachian territory to the British from the French at the end of the Seven Years’ War, more easily visible in a detail of the area around Fort Loudon.

Willem De Brahm, 1717-ca. 1799], “A Map of the Indian Nations in the Southern Department,” 1766.

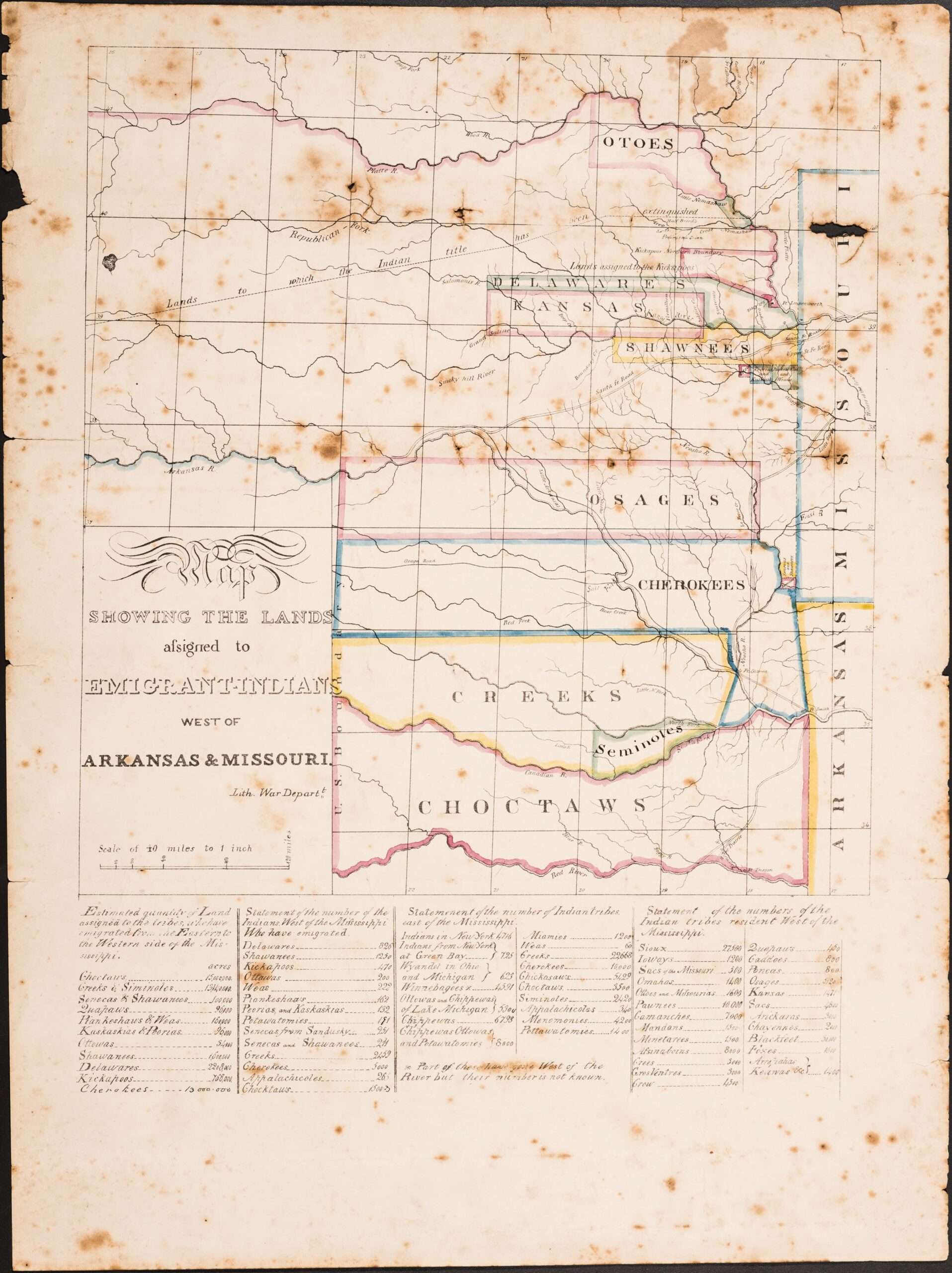

Such maps emphasized the indigenous American presence in regions where European settlers were expand – ing their own footprint. Farmers and settlers of European descent pushed into these western lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, with tragic results for Native Americans. Soon designated as “emigrant Indians” the several groups who spread out in the Southern territory on the De Brahm map were squeezed into a much smaller area in what is now eastern Oklahoma, as shown on the War Department map of 1836 (next page). Colored lines indicated boundaries of lands of 10 displaced Native American groups in the wake of the Indian Removal Act (1830), which authorized the federal government to extinguish all Indian title to the lands in the deep South, and 60,000 souls set out on the Emigrants Walk (or Trail of Tears).

Map Showing the Lands Assigned to Emigrant Indians West of Arkansas & Missouri, produced by the United States War Department ([Washington, D.C.], 1836).

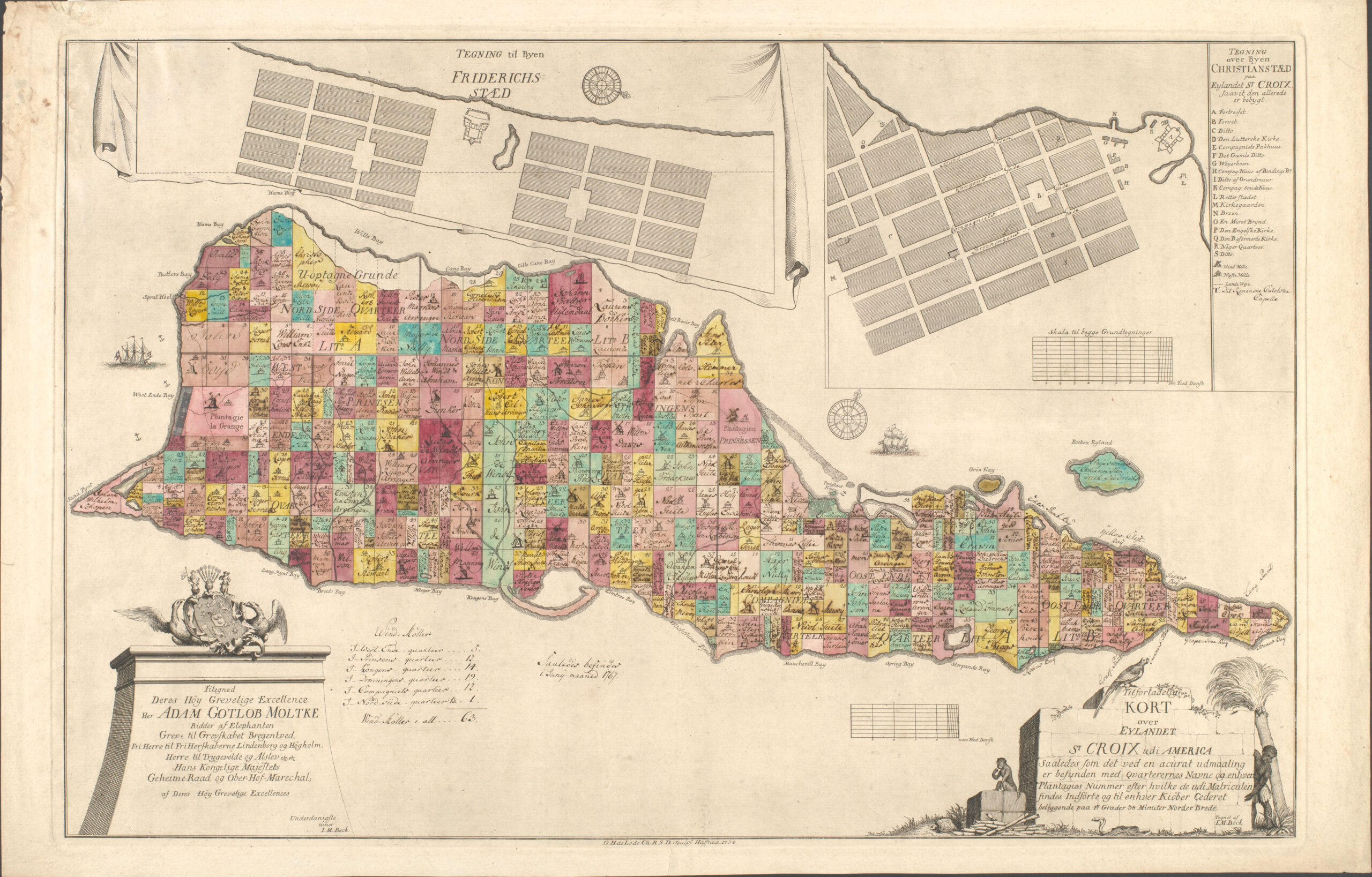

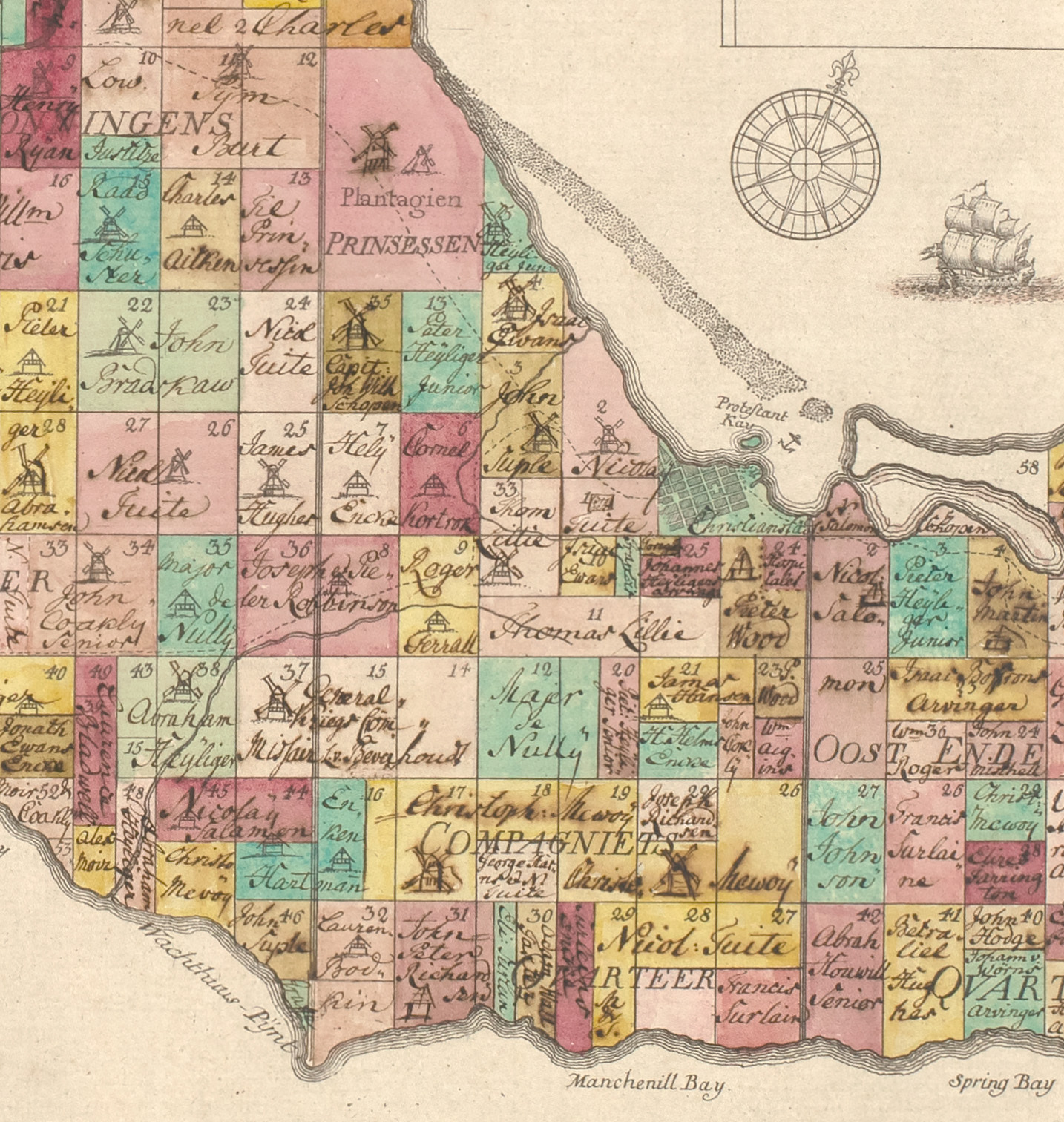

While Native Americans were pushed westwards, forced emigration peopled North America and the Caribbean islands with enslaved individuals. Despite or perhaps because of fears of the growing Black population, the African American presence as forced labor on plantations in the American South or the Caribbean islands was rarely visualized. However, one can discern the size of a plantation and extrapolate the number of slaves required to work in the fields or process sugar (the main export from the islands) from the plantation surveys frequently executed on the islands. A recent research project looked closely at the island of St Croix, a Danish colonial holding, and the depiction of two types of mills used for crushing the sugarcane: wind and animal driven. These mills were built and operated with Black labor, as the cartouche shows. The detail reveals the various sizes of plantations and the number of mills on each, a determining factor in the value of the holdings.

Hidden narratives of race, culture, and space lie under our noses as we study maps. Recent research on one of the Library’s prize atlases has illuminated a link to an annual celebration of historical events In San Pedro Huamelula, Mexico, in which the indigenous Chontal people reenact the invasion of Lan pichilinquis — the Chontal term for “pirates.”

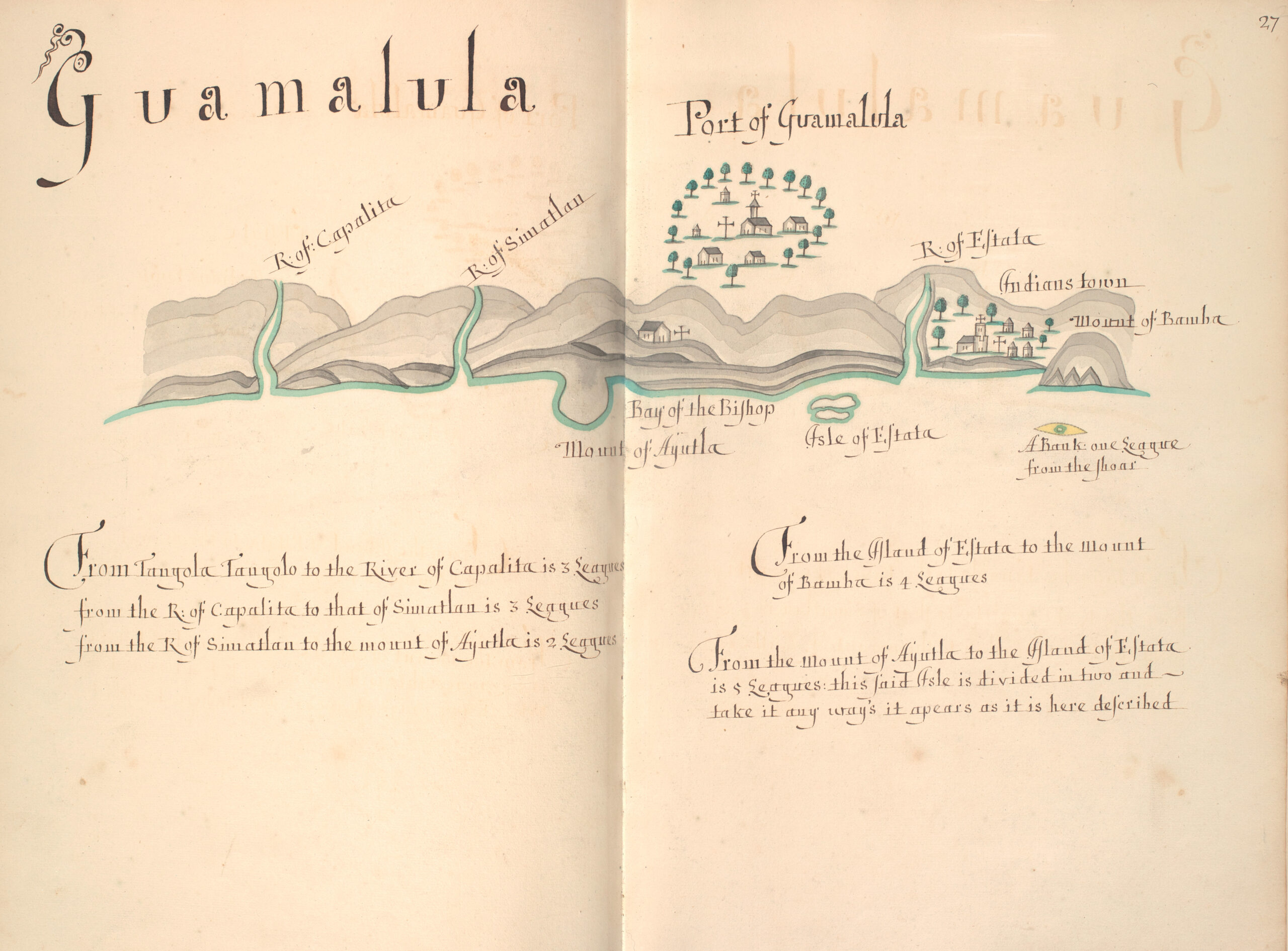

The pirates who invaded Huamelula may be linked to the buccaneer source of the one of the Library’s prize atlases: English chartmaker William Hacke’s atlas of 1698, a volume of 184 manuscript charts of the Pacific coast of America, one of at least 14 editions of this atlas produced in the 1680s and 1690s. The maps in the atlas were based on charts seized by English buccaneers in 1680 from a Spanish ship which were then requisitioned for their own raids on settlements up and down the Pacific coast, from Acapulco to Chile.

Throughout the Hacke Atlas (officially titled, “From the Original Spanish Manuscripts & our late English Discoveries A Description of all the Ports Bay’s Roads Harbours Rivers Islands Sands Shoald’s Rocks & Dangers in the South Seas of America,” hence the commonly used abbreviated title) are over a dozen brief references to various indigenous groups along the Pacific coast, noting who was friendly or hostile to the Spanish or English. Most of these “ethnographic” details do not appear in the original Spanish chart, as Spanish seafarers could typically rely on safe ports and bays controlled by the Spanish Crown; but competing English sailors were always concerned with the precise location of freshwater sources and isolated bays where ships could replenish and careen.

Jens Michelsen Beck, Tilforladelig Kort over Eylandet St. Croix Udi America ([Copenhagen], 1754)

Folio 27, “From the Original Spanish Manuscripts & our late English Discoveries A Description,” by William Hacke, 1698. Guamalula is present day Huamelula on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

On folio 27 of the Hacke Atlas, the Chontal community is glossed “Port of Guamalula” on the coast, although its location was and is inland; it is termed “Pueblo,” or town, on parallel Spanish atlases. Archaeological surveys have confirmed that this was the Chontal community’s original location, before pirate attacks forced the inhabitants to resettle further inland in the late 17th or early 18th century. This displacement is performed in the choreography of Huamelula’s annual reenactment, in which traditional Black characters may represent runaway enslaved Africans who sided with the Chontal to fight and repel foreign invaders. The roles of the reenactment festival echo historical identities of Chontal, pirates, and slaves—three disenfranchised but numerous groups who operated on the periphery of the Spanish Empire in a network of of competitive alliances, vying for land and trade.

The importance of using the past to understand the present cannot be underestimated. To quote Clements researcher, Danny Zborover, 2020–2021 Mary G. Stange Fellow, who brought the connection between the Hacke Atlas and the indigenous Chontal inhabitants of Huamelula to light and life: “by integrating archival research with interdisciplinary fieldwork and community outreach, the Clements Library’s Hacke Atlas and similar sources open a window into a fascinating yet untold story, one in which the Chontal and other Indigenous people contributed directly to the formation of the early Transpacific Modern World.” To paraphrase the ancient writer Cicero, our lives are woven from the threads of memory of previous times and peoples.

— Mary Pedley

Assistant Curator of Maps

- Evolution of an Archive

- “Who Knows but a Woman May One Day Preside Here”

- The Threads That Bind Us

- Illuminating Revolutionary War America

- Elegant to Eccentric

- Mysteries of the Deep

- Mapping Research Trends in the Collections

- Recent Acquisitions

- Philanthropy Builds the Archive and is Recorded There, Too

- Announcements — Winter/Spring 2023