Transatlantic Visions

TRANSATLANTIC VISIONS

Today we understand the origins of Edward W. Clay’s satiric concepts, and they are trans-Atlantic rather than local in their proportion. Clay’s visual vocabulary of race, as exemplified by “Life in Philadelphia,” grew as much out of the artist’s engagement with his peers in London and Paris as it did from his encounters with African Americans in Philadelphia. The recent discovery of Clay’s early watercolors and scrapbooks produced during his travel in France toward the end of the 1820s offer a window into the trans-Atlantic influences that gave birth to Clay’s subsequent depictions of black Americans.

This European sojourn opens the door to new understandings of the “Life in Philadelphia” series, which Clay published shortly after returning to that city from Paris in 1828 and this re-reading of Clay’s images promises to rewrite the history of race and racism in America. Copying and reinterpretation have long been part of the culture of caricature and we see evidence of Clay’s study of Thomas Rowlandson and his borrowings from the Cruickshank brothers. His work also reflects encounters with Edmé-Jean Pigal, Frédéric Bouchot, Achille Deveria and popular series including the Petit Courrier des Dame and Le Bon Genre. Parallels to his contemporary Honoré Daumier are evident. Clay’s sojourns draw attention to how these well-remembered social satirists also took up the black subject, incorporating black men and women into their commentaries on London and Paris in the 1820s.

His images and ideas were a precursor to American minstrelsy and were rooted in a vocabulary of caricature and parody with roots in Europe rather than the United States. However, as his Paris work suggests, Clay’s ideas were born, not only out of antebellum America, but out of late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth century Atlantic world perspective of race and difference.

Edmé-Jean Pigal (1798–1873)

“Contrastes, ‘Maître à moi !… nois pas blancs!’”

Ca. 1820s

Facsimile of: lithograph, hand colored, 34 x 25 cm.

Image courtesy Musée d’Aquitaine, Bordeaux

Pigal was among Paris’s most prolific caricaturists during the period of Clay’s visit. This parody of two black servants was part of the artist’s series Médailles ou Contrastes published between 1822 and 1830. “My master is not white” becomes a play on the words black and white, which also mean drunk and sober. In this caricature, the meanings of drunk and dark skin color are fused.

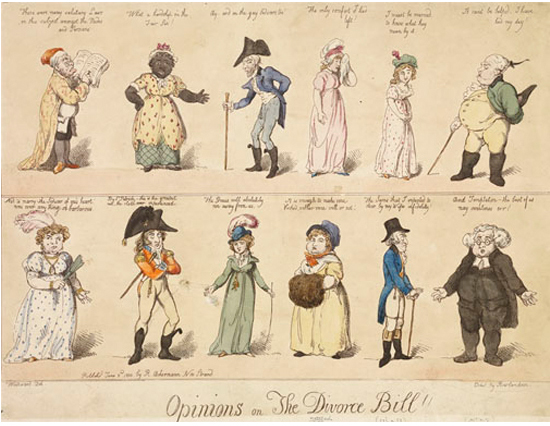

Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

“Opinions on the Divorce Bill!!”

London: R. Ackermann, 1800

Facsimile of: etching with watercolor, 34 x 47 cm.

Image courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In the spring and summer of 1800, the British Parliament debated the terms of a new divorce bill that would prohibit those guilty of adultery from marrying the party with whom they had committed the offense. Rowlandson suggests how various social types viewed the proposed legislation, with the black female figure in the upper left remarking “What a hardship for the Fair Sex!”

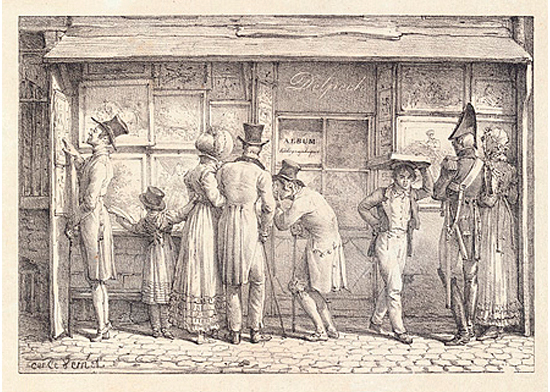

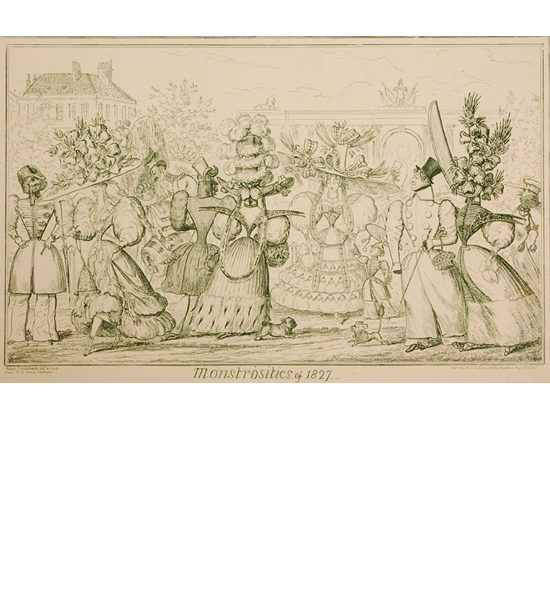

Robert Cruikshank (1789–1856)

“Monstrosities of 1827.”

London: Thos. McLean, 1835

Etching, 37.5 x 53 cm.

William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan

Cruikshank’s “Monstrosities” series, which spanned from 1816 to 1827, held out fashion taste as a defining aspect of London’s urban gentry. In his 1827 scene, the artist also suggests how a sort of decadence was possible in such scenes as the woman on the left exposes her leg to a male admirer.

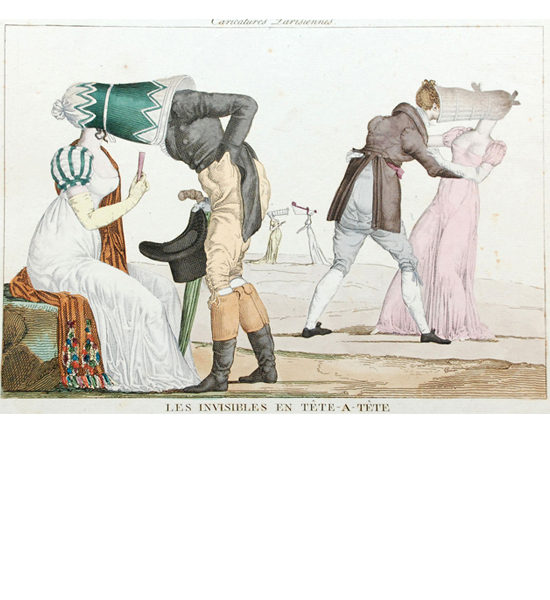

“Les Invisibles en Tête-a-Tête. Le Supréme Bon Ton No. 16.”

Paris: Martinet, ca. 1815

Facsimile of: engraving, hand colored, 31 x 43 cm

In: [Le Supreme Bon Ton, Paris: Martinet, 1815?]

Image courtesy Sterling and Francine Clark Institute

Women’s bonnets were a theme that reoccurred in French, British, and American caricature, including Clay’s “Life in Philadelphia.”