TINY THINGS

No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

Table of Contents

“A Just and Perfect Inventory” in Miniature

By Iman Jamison

Manuscripts Division Intern

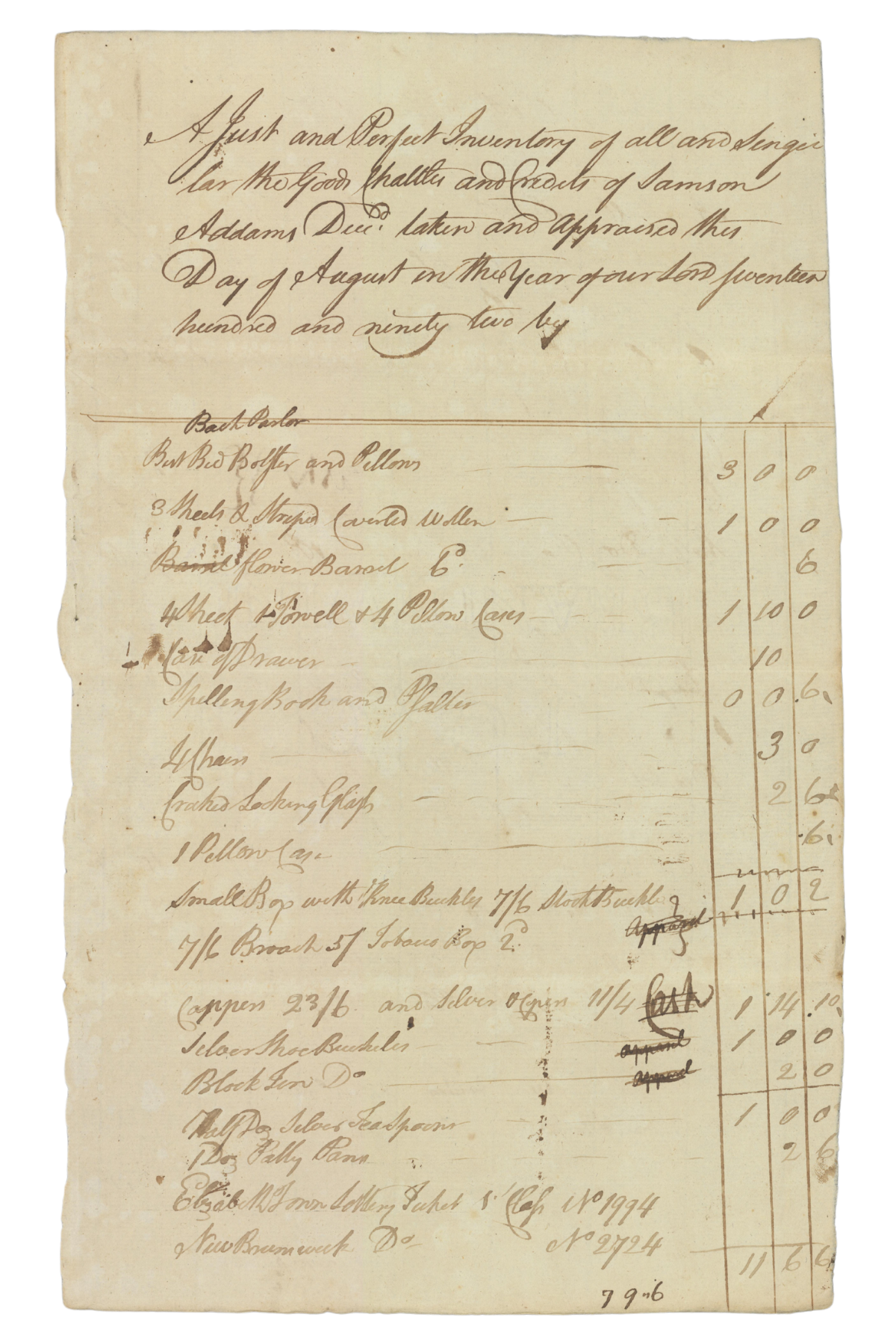

“Ms. Inventory of the Samson Adams estate, August 1792,” in the digital collection, Samson Adams Papers, 1767–1794.

The Clements Library houses thousands of records, ephemera, lists, and inventories that reveal the rare stories of lives lived long before us. As a recent history graduate, I am honored to have had the opportunity to gain glimpses into these stories, whether they be of a missionary traveler in the late 18th century or the 19th-century letters of an antislavery activist. However, out of my four years at the University of Michigan, one particular story comes to mind, woven together by “little pieces” of inventory.

During the Winter 2024 semester, I was a student in Matthew Spooner’s class, Silences of the Archives: Slavery and the American Revolution. While searching for archival records relating to African Americans, we often lose access to the humanity of those we are researching. The hands-on work we participated in at the Clements allowed my classmates and me an understanding of the missing pieces of the historical memory of African Americans during the Revolutionary War-era. To this end, we looked through the letters and records of the British anti-slavery advocates as well as the ephemera and manuscripts of Black Americans themselves.

During one class session, I was introduced to Samson Adams, a free African American of the late 18th century who resided in New Jersey and worked as a trader, carpenter, and laborer while taking care of those around him. He left a legacy of economic success and community, bequeathing his estate to his brother and sister as well as to the “Episcopal, Presbyterian and Methodist churches in Trenton” and “a small sum for the poor of the city.” The Samson Adams papers, which span 1767 to 1794, contain the estate and business documents for Adams’ time in Trenton, New Jersey, including the estate inventories drawn up following his death.

“A Just and Perfect Inventory of all and Singular the Good Chattles . . . of Samson Addams . . . taken and appraised this Day in August in the Year of our Lord Seventeen hundred and ninety two . . .” can be read at the top of one of these inventories. One can see a list of the objects from his home, organized by the rooms in which they were found. Items such as a flour barrel, bed bolster and pillows, spelling book, and a “Cracked Looking Glass” are just a few of the occupants of Adams’ back parlor.

As a class, we were tasked with reading these inventories and interpreting the significance of the document’s presence in the archive. However, Jayne Ptolemy, Associate Curator of Manuscripts, and Maggie Vanderford, Librarian for Instruction and Engagement, did not stop there. They presented us with the opportunity to not only read these inventories but engage with and visualize the life of Adams through tiny pieces of paper.

With our inventories in hand, we scoured a table filled with miniature paper cut-outs representing the objects present on the list—objects that lived in the rooms of Adams’ dwelling. One by one we found each item on the inventory and its corresponding cut-out and recreated what we imagined his back parlor and bedroom may have looked like. We were asked questions about how we thought his rooms might have been organized: Was there a reason the cracked looking glass is followed by a pillowcase on the inventory for a room supposedly used for the reception of guests? Why was there a spinning wheel in Adams’ bedroom? What was the significance to how he stored his belongings or is the significance lost simply because of how the author of the inventory chose to order them?

The small rooms we created presented us, as historians-in-training, with a way of envisioning the life of Samson Adams, highlighting the silences so often present in African American history. These seemingly mundane lists and inventories are the exact artifacts of history that help answer our questions, and also leave us with new mysteries. The tiny replicas of his estate were instrumental in that process. I will always wonder if the images on our little pieces of paper truly resembled the objects scattered around the rooms of Adams’ estate, a visualization of the legacy of a free African American man building economic gains when the odds were very much against him.

The internet was scoured by Clements staff to locate representative images of items listed in the Samson Adams inventories.

“1 Bed spread Patchd work Bed and Sundry Cloths on it Bedstead &c” (Bed, Object Number 1981.0010, Winterthur Museum Collections)

“Two flower Barrels & C[ontents?]” (Wooden Flour Barrel, Warwickshire County Museums)

“Bellows” (Bellows, Object umber 1957.0787, Winterthur Museum Collections)