Native American Spaces

Native American Spaces Subject Guide

Overview

The William L. Clements Library offers an expansive and growing collection of materials related to Native American territoriality and place-making, mapping and boundaries, geography, and land use and land tenure practices broadly understood. Historians, ethnographers, and other researchers mine sources like European maps that indicate Native villages and population centers, printed accounts of exploration that include passing references to agricultural or hunting practices, or 19th-century photographs of Native peoples. Sources like these, among others found at the Clements, help illuminate the spatial dimensions of Native American power, demarcation and maintenance of external boundaries by Native social formations, and configurations of space within Native American societies.

Important manuscript collections include the Josiah Harmar papers, 1681-1937, Standing Rock Indian Agency Papers, 1876-1906 and the Great Britain Indian Department Collection, but relevant materials are available across Clements Library divisions. The Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection and the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography are notable examples from the Graphics Division. Many other digitized manuscript and cartographic documents, such as Guillaume Delisle’s 1703 Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France, are available in the Clements Library Image Bank.

Readers are encouraged to consult the Method section of this guide for examples of interpretation and analysis. Related Subject Guides on Cartography and Native American History may also be useful.

Selected examples of the resources to be found in each division include:

Book Division

- Published Treaty texts and Council proceedings

- Journals of missionary activity

- Printed accounts of exploration and discovery

- Survey records, often including cartographic material

- Frontier or homestead narratives

Manuscript Division

- Fur trade and mercantile papers

- Diaries and letters of travellers and missionaries

- Original accounts of military figures, explorers, and others who travelled through Native American lands and territories

- Papers of military figures, Indian agents, government departments, and agencies

Graphics Division

- Photographs of Native American villages, seasonal or temporary settlements and encampments, hunting and fishing activities

- Promotional tracts

- Printed illustrations of Native people and settings

- Personal and commercial photography of Native Americans

- Original artwork like sketches, paintings, and ledger art and drawings of Native people, encampments, village sites

Map Division

- Printed maps of North America 1500-1900

- Manuscript maps and plans indicating natural resources, environmental features, village sites and broader territorial boundaries and spaces of Native polities

- Emigrant, tourist, transportation and route maps way-finding

- Cartouches depicting Native American content

Method

Manuscript and Cartographic material covering topics like Native American land use and land tenure, territoriality and place making, and territoriality and borders are available in abundance at the Clements Library. Book Division materials include many published works containing unique maps and cartographic content not found elsewhere. The bulk of this material was authored by European and later Anglo-American authors, and not Native American or Indigenous peoples. As such, these materials represent the biases and judgements of the authors. Proceeding with caution, one can sensitively address these limitations.

Manuscript Materials

The George Clinton papers, 1697-1760 (bulk 1745-1753), Lewis Cass Papers, 1774-1924, and Thomas Gage Papers, 1754-1807 (bulk 1759-1775) are noteworthy collections documenting Native American spaces, territoriality, and land tenure and land use. Personal correspondence, warrants and other legal documents like deeds, speeches, diaries, invoices, financial records involving Native Americans, and translations of Indian councils and speeches by Native leaders are just some of the material within these large collections documenting military and economic administration of colonial North America. Native voices appear frequently in these documents, but translation problems and misunderstandings borne of cultural differences and biases mean that such references should be carefully analyzed. Papers of mercantile figures like fur traders and merchants, or interpreters who could speak European and Native American languages, complement these governmental or military sources and contain similar information on Native American spaces. The James Sterling Letter Book and John M. Johnston collection are prominent examples. Below, please find a brief interpretive analysis of a letter penned by Sterling:

In a 1762 letter to a business colleague, Irish fur trader and merchant James Sterling described the movement of local Native American groups as they traversed back and forth between the Detroit area and winter hunting grounds: “The Indian Trade is but dull at present but will be very good, I believe, and some Indians who come in from hunting say that Game is uncommonly plentiful this year.” (James Sterling Letter Book, 10 Jan 1762, pg27)

This brief passage, part of routine mercantile correspondence, sheds light on the movements of Native groups that lived near to Detroit. Seasonal movement tracks onto the availability of game, which scholars see as part of the regular movement of semi-sedentary peoples throughout a larger traditional territorial range of hunting grounds, villages, and other sites. These references often invite more questions than they answer, but can be important starting points for research. Indeed, it is not immediately clear who Sterling referred to; local Potawatomi, Ottawa, Huron, Delaware, or Ojibwe groups. Some manuscript materials, particularly accounts and narratives of early explorers, mention documents or objects given by Native polities to Europeans that functioned like passports, and served to mark the bearer as an individual known to surrounding communities. Such items may be mentioned in narrative accounts. The specific tribal or village identity of a Native guide can also be revealing; familiarity with the ground and routes and trails suggests spatial knowledge of the region and distances between points. Another useful guide is to think of Native American villages or village sites not as atomized entities but part of larger interconnected formations. In this way, a European traveler’s description of a single village site may actually hinder understanding of the larger territory or range of the described Native group.

Cartographic Materials

Maps may not suggest by their title that they contain information on Native American communities or territories, but it pays to look closely at a map’s contents. Seventeenth and 18th-century French cartographers showed a concerted interest in placing Native American communities and what French colonists perceived as “nations” in the spatial world of New France or Canada (itself an aboriginal term, first encountered by Champlain). This is seen clearly on Guillaume Delisle’s 1703 Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France.

Detail from Guillaume Delisle, Carte du Canada ou de la Nouvelle France, 1703.

Many library catalogs truncate the long titles of maps, limiting the title to just the area depicted but not including further information in the title about the purpose of the map. Searching broadly in the catalog for the regions of your study, reading the catalog description for further information, and looking at the content of the map first-hand will help scholars fully mine the map holdings. A section from a well-known, highly-detailed example from 1755 is below:

Evans’ work stands out as a singular spatial depiction of territory between what he terms as the “middle colonies”—that is, southern New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and Virginia—and the Mississippi River. As the full title of the map tells us, one of the purposes of Evans’ work was to show the places of residence, the deer hunting country, the beaver hunting country, and the ancient and present seats of the Indian nations. Evans also prepared an essay as an analysis of the map, accounting for his observations, his sources, and his methods of compilation, which enhance our understanding of his purpose and how to read the map. As with all cartography, the map benefits from a close perusal in order to glean the vast amount of information on Native American territories in the trans-Appalachian west.

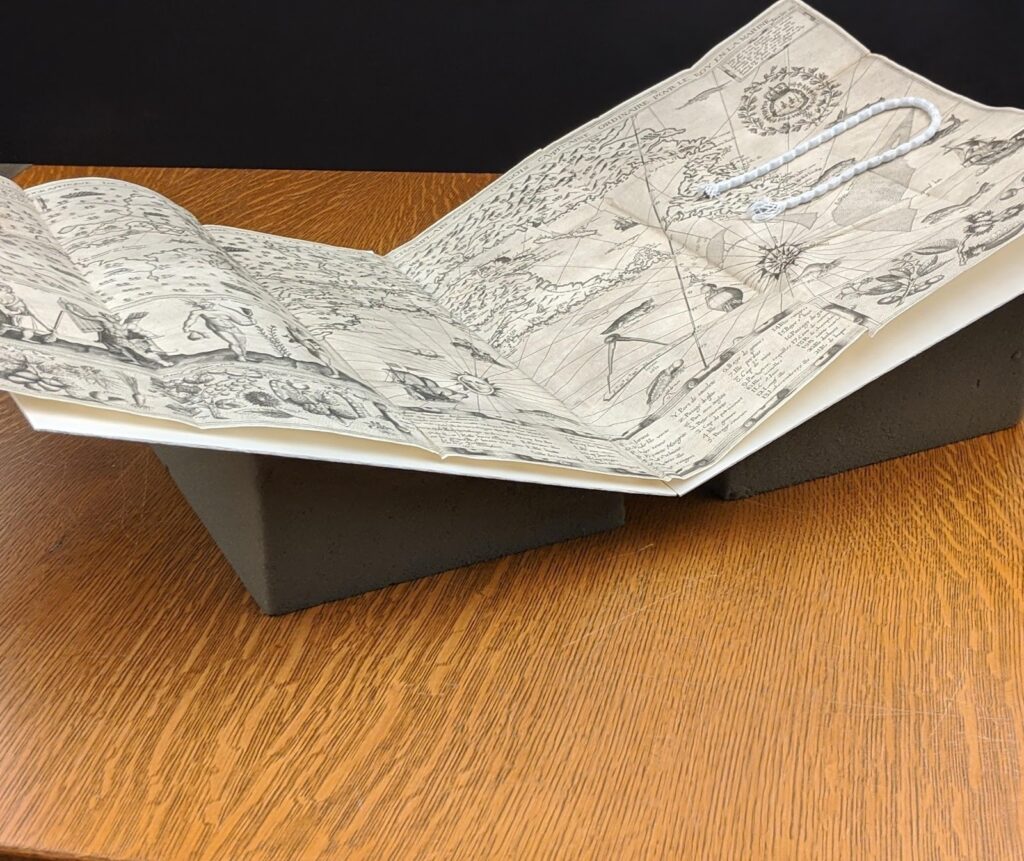

Book Materials

In addition to an extensive collection of atlases, published items residing in the Book Division and particularly the rare book collection are rich in maps and cartographic content relating to Native America. Books with such material can be found across different time periods, from fold-out maps of fur trade and exploratory voyages in 17th-century vellum bound books to 18th- and 19th-century children’s geography textbooks. Many of these maps are not separately cataloged, so we encourage researchers to contact curators for more detailed information about a particular item. Below are a few tips that will help identify cartographic content within Book Division materials.

The physical description section of the catalog record for the above item, a 1613 edition of Champlain’s Voyages de la Nouvelle France, specifically mentions folded leaves of plates with illustrations and maps. To find similar items within the Book Division, curators suggest keywords or search terms that aid in identifying maps or cartographic content within books. The following terms are particularly useful: “map,” “maps,” “color maps,” “fold. map,” “ill.,” “plates,” and “illustrations.” An effective strategy is to pair a key word (map, maps, etc) with a geographic reference point, then to filter results within the catalog by selecting Format “Books.” Conducted this way, a search for “maps Dakota” reveals wide-ranging results like the printed records of the Indian Rights Association, business manuals or directories from towns, promotional tracts, or government correspondence by local and state-level politicians. Many of these items have unique cartographic content. One could also pair key words with a particular Native group, a particular historic event or conflict like Pontiac’s War, or a historical process like Indian Removal. Mindfulness of the place of publication, or broader geographic region, can identify publishers and help grapple with the spatial dimensions of knowledge production: where books with Native American content originated, for example, or where major publishing houses of such content operated.

Periodicals

The Clements Library holds a significant quantity of pre-1900 periodicals including newspapers, magazines, and journals. Many of the materials within popular databases like the American Antiquarian Society (AAS) Historical Periodicals Collections and the Early American Newspapers Series (Readex) are part of our collections, and we strongly encourage accessing the physical documents. Researchers are encouraged to contact curators for more information about our large collection as well as for advice on accessing and searching our holdings. Native American peoples, landscapes and environments, and territorial boundaries and borders appear in these materials through textual description or narration and also through maps, graphics, and illustrations. American territorial expansion, for example, was a historical process well-documented by journalists and reporters who sought to describe the West, and its peoples, to American and global audiences. Materials produced during the Colonial and Early Republic eras contain similar content. Unique maps and illustrations accompanied stories and news reports, and readers can expect to encounter maps and illustrations of various scales in different periodical formats. As with fold-out maps and plates in published works, these materials are not cataloged independently from the periodical itself. Importantly, and just as with manuscript sources, readers should stay mindful of authorship and the biases and attitudes that informed the production of these materials. Consideration for the intended audience of a piece is another useful approach.

Visual Materials

The Clements Library’s visual collections include images of Native American presence from the 16th century into the 20th. Almost all of these images reflect the perceptions of Anglo-European artists and not self-depictions from Native Americans. Included are the works of colonial explorers, traveling tourists, expedition artists, professional photographers, each with a different motive and audience. These images are often best placed in context with other archival materials as the tension between the subjects and the image makers was often high. The earliest images in the library’s holdings appear as book and map illustrations. The Graphics Division holdings of stand-alone prints begins for the most part in the 18th century. Nineteenth century photographs can be used as a resource for tracking large historical events in Native American history such as the expedition of the United States Army into the Black Hills and the Battle at The Little Big Horn, as well as representing indigenious settlements and temporary encampments. Photos can also locate individuals at a particular time and place, and reveal the complexity of the trade in material culture among tribes. Many portrait lithographs of tribal leaders were created from sketches done at treaty signings both in western territories and in Washington D.C. These can be used to trace the movements of specific individuals relative to the changing regulations of land occupation and ownership.

Subject Headings

Readers are encouraged to think of a broad range of potential subject headings and keyword search terms. Particular focus on the when and where—outlining a chronology and establishing geographic parameters—can yield results in expected and unexpected places. Subject headings do not, of course, reflect the entirety of the information conveyed. Forestry and railroad survey maps, for example, contain rich detail on the precise locations of Native American villages, but are often identified with subject headings more in keeping with the precise utility or purpose of the surveys and maps (railroads, real property, minerals and resources, etc). Here it will be useful to apply U-M Library Search filters, and to experiment with Date of Publication, Region, Author, and Format options, in addition to the Subject filter.

It is also important to pay attention to naming or identity conventions associated with particular Native American groups, and how these conventions, terms, and names have changed over time. “Potawatomi,” “Pottawatomi,” “Pottawatomie,” and “Bodéwadmi,” for example, are names or ethonyms for the same Native American group. Broad linguistic and cultural categories like “Algonquian” or “Anishinaabe” are also useful, but it is important to remember the large and diverse number of names of tribes, polities, and nations within these larger groups. Terms like “Native Californian” and other labels associated with a particular region or state refer to historical and contemporary Indigenous populations residing there, including Cahuilla, Mohave, and many others. Knowing these variations and identifiers can help with a more thorough and productive search.

Selected examples of relevant subject headings include:

Aboriginal

Algonquian

America–Discovery and Exploration

Cartouches (North American Indian)

First Nations

Frontier and pioneer life

Fur trade

Gage Maps

Harmar Maps

Indigenous

Indian agents

Indian captivities

Indian encampments

Indian interpreters

Indian reservations

Indians of North America

Indians of North America–Biography

Indians of North America–Canada

Indians of North America–Commerce

Indians of North America–Education

Indians of North America–Government relations

Indians of North America–Languages

Indians of North America–Missions

Indians of North America–Mixed descent

Indians of North America–Religion

Indians of North America–Relocation

Indians of North America–Social life and customs

Indians of North America–Treaties

Indians of North America–Wars

Indigenous peoples

Manuscript maps

Maps shelf

Missionaries

Native American

New France

New France–Discovery and exploration

Railroads

Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography

Rites and ceremonies

Trading posts

Travel literature

Tribal chiefs

United States–Army–Indian Scouts

United States–Discovery and exploration

United States–Office of Indian Affairs

Warriors

Wheat Maps

This is only a small sample of relevant subject headings. Researchers should contact the library for more information on keyword or subject-based catalog searches.

Bibliography

Barr, Juliana. “Geographies of Power: Mapping Indian Borders in the “Borderlands” of the Early Southwest.” The William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 1 (2011): 5-46.

Brooks, Lisa. “Awikhigawôgan ta Pildowi Ôjmowôgan: Mapping a New History.” The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2018): 259-294.

Brückner, Martin, ed. Early American Cartographies. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

De Vorsey, Louis. The Indian Boundary in the Southern Colonies, 1763–1775. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966.

Edelson, S. Max. The New Map of Empire: How Britain Imagined America before Independence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017. Especially Chapter 4, “Marking the Indian Boundary,” 141-196.

Furtado, Júnia and Neil Safier, “Indigenous Peoples and European Cartography.” In The History of Cartography, Volume Four: Cartography in the European Enlightenment, edited by Matthew Edney and Mary Pedley, 663-672. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Greer, Allan. Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires and Land in Early Modern North America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Lewis, Malcolm G. Cartographic Encounters: Perspectives on Native American Mapmaking and Map Use. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Lewis, Malcolm G. “Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans.” In David Woodward and G. Malcolm Lewis, ed., The History of Cartography, Volume 2, Book 3: Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Pleasant, Alyssa Mt., Caroline Wigginton, and Kelly Wisecup. “Materials and Methods in Native American and Indigenous Studies: Completing the Turn.” The William and Mary Quarterly 75, no. 2 (2018): 207-236.

Rose-Redwood, Reuben, Natchee Blu Barnd, Annita Hetoevėhotohke’e Lucchesi, Sharon Dias, and Wil Patrick. “Decolonizing the Map: Recentering Indigenous Mappings.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 55, no. 3 (2020): 151-162.

Tanner, Helen Hornbeck. Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987.

Witgen, Michael. “The Rituals of Possession: Native Identity and the Invention of Empire in Seventeenth-Century Western North America.” Ethnohistory 54, no. 4 (Fall 2007), 639-68.

Online Resources

Last Updated 1/22/21