No. 60 (Fall/Winter 2024)

One is the Loneliest Number

Paul J. Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director

William L. Clements Library

“Tiny Things” may seem like an unusual theme for a Clements Library Quarto. Like most of our peer institutions, we often tend to focus on big things: the largest collection of this, the deepest holdings of that, the longest shelves, the most titles by Author X. We love our Audubon folios. We celebrate the acquisition of flashy, famous items, which are also often large. Librarians and scholars alike are drawn to materials from the past that had an impact—books that were the biggest sellers, that were read by the most important people. And I’m as guilty of this as anyone. A book that was published that nobody read is kind of like the tree that falls in the forest with nobody around to hear it.

The three-volume publication, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, (Philadelphia, 1845-1848) resulted from a collaboration among John James Audubon (1785–1851), John Woodhouse Audubon (1812–1862), Victor Gifford Audubon (1809–1860), naturalist John Bachman (1790–1874), and lithographer William Hitchcock (ca. 1823–ca. 1880); at 72 cm, this “Imperial folio” edition was printed by J.T. Bowen.

Even the way we store our collections privileges big and weighty artifacts. Our biggest books—which we call folios—have their own shelves. Meanwhile, our smallest printed books are batched together in acid-free boxes in the “Pamphlets” and “Juveniles” section of the stacks. This all makes perfectly good sense, of course. Given our interest in using space as efficiently as possible, it’s entirely logical to store the largest books on the tallest shelves. And from the perspective of preserving our fragile collection items, storing small children’s books and paper-covered pamphlets in boxes protects them from the damage they would suffer if they were on open shelves with the rest of the collection.

This issue of The Quarto asks you to pick up a magnifying glass and think small. The pieces in this issue focus on small books, small maps, small pictures, or books about small things. Miniature books and prints are often wonderful examples of the art and craft of bookmaking and illustration. The challenge of creating a tiny version of a book that still functions as a book is a test of the skill of printers and binders alike, and many collectors are drawn to these items for just this reason.

But what if we come at the question of tiny from a different direction? Instead of thinking about small things, what if we thought about small audiences? My interest in books from the past grew out of an interest in readers from the past, which is to say that I was interested in the audience. When I read an 18th- or 19th-century American book, I often think more about who would have read it and how than I do about who wrote it or who printed it. So in thinking about “tiny things” for this issue, I was led to think about readers rather than books themselves.

Of course, how books are produced has a direct bearing on how many people read them. In his book Popular History and the Literary Marketplace, 1840–1920 (Amherst, Mass., 2008), Gregory Pfitzer offers what is my favorite definition of “popular” literature. He writes that “popular” printed items are things for which “every aspect . . . was designed to increase sales.” Which is to say that a “popular” book was one that was written, printed, bound, and sold in ways that were very specifically intended to sell more copies. Now, you might reasonably ask, “Doesn’t everybody who prints books want to sell as many copies as they can?” To which I would reply, “Does Rolls Royce want to sell as many cars as they can, or do they want to sell a small number of cars to very specific people?” Some books are Rolls Royces, deluxe items meant to generate a large return from each single copy sold to an elite market. Other books are Honda Civics, meant to generate small returns from a huge number of copies sold to just about anybody. And if you browsed the shelves of the Clements Library’s stacks, you’d be able to pretty easily tell the Rolls Royces from the Hondas, just as you would in a parking lot.

What I’m really interested in are things that look like Honda Civics but were made for a Rolls Royce-sized market—that is, things that were cheaply made but intended for a tiny audience. I’m both fascinated and delighted by the amount of labor that people in the past put forth to create something that just a handful of people, or maybe only one person, would ever see, using processes that were developed for mass circulation.

Corn husks are now used in boutique paper products, but the process for creating the fragile husking party invitation in 1885 would have been time-consuming and labor-intensive.

One example of this that I especially love is a recently acquired invitation to a “Husking Party” in West Springfield (it’s not clear which one—there are five “West Springfields” in the United States) in September 1885. The invitation was printed on the most appropriate and the most ephemeral possible material: a corn husk. Maybe more than one person saw this invitation, but given that it survived, it almost certainly wasn’t passed around. Yet William Thomas had to go to the trouble to collect enough corn husks to generate a good crowd for his party. He had to trim them to size and flatten them so that they’d take ink. And he had to set type—using four different typefaces—that would actually print on the husk. All this work, for something that was intended for only one person to see.

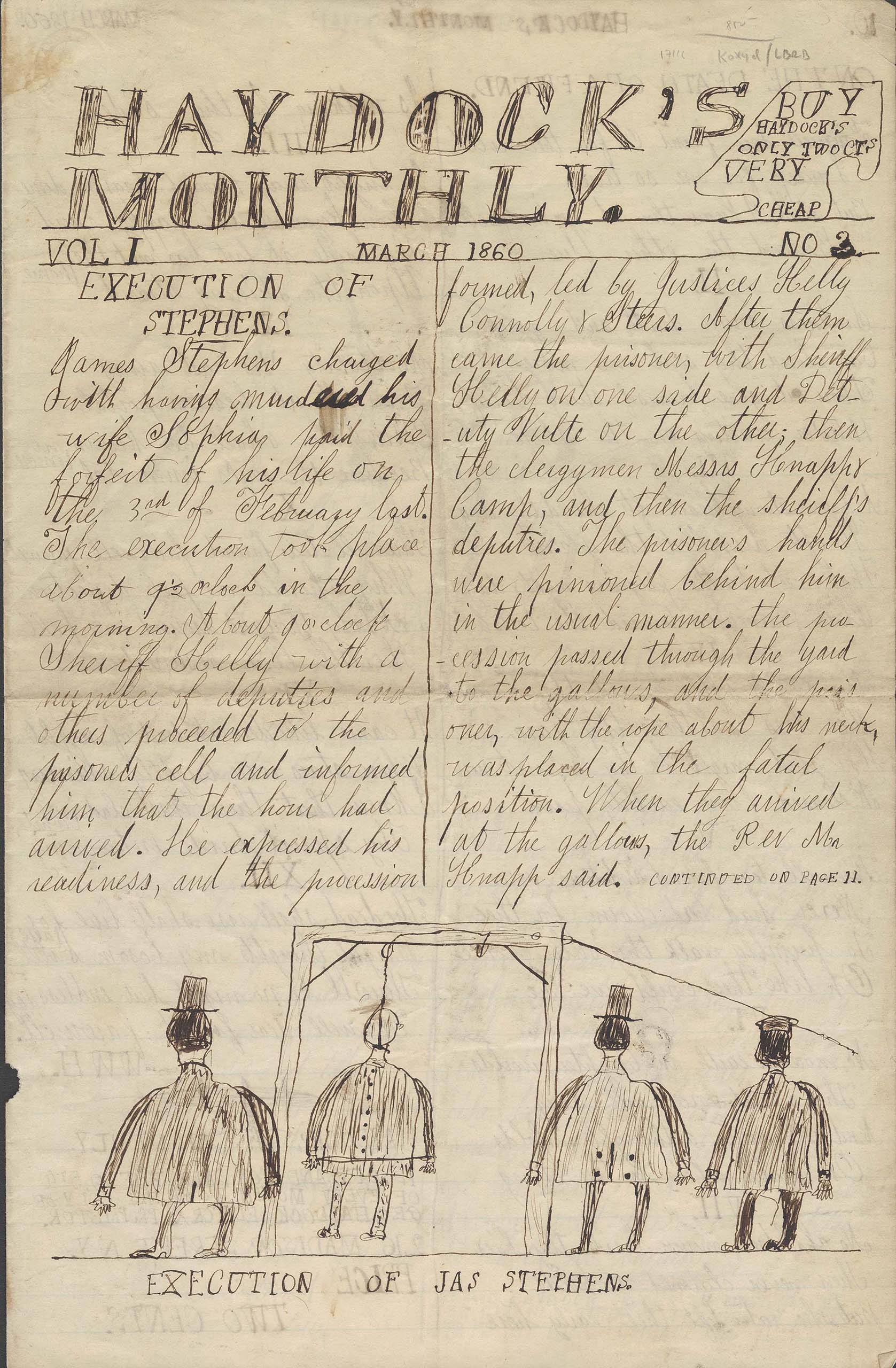

Many manuscript items, such as letters, were only intended for an audience of one, and the fact that they’ve wound up in a place like the Clements might surprise their authors, since generations of scholars are now able to read their private thoughts. But some manuscript forms were created to mimic forms of print that were intended for wider circulation, although they still likely only reached a few individuals. The Clements holds several examples of manuscript newspapers—hand-written versions typically created by children that mimic the appearance of printed periodicals. Some focused solely on news that was relevant to the author’s household, such as what the cat had been up to. Others, like George Haydock’s “Haydock’s Monthly,” “published” in New York City in March 1860, presented a version of a real news story (about the execution of a man convicted of murdering his wife), complete with an illustration of the gallows. The subscription information included on page 10 of the issue lets the small readership know who to pay their two cents for the next issue. The time and effort that George Haydock put into hand-writing copies of his newspaper (who knows how many?) very likely “did not come close to justifying the per issue price, given that his audience likely numbered in the single digits.

Reading items like these, that were produced for a tiny number of readers, can feel like eavesdropping on a conversation. William Thomas’ party invitation was created to be circulated, but the copy at the Clements was almost certainly intended for only one person. And George Haydock’s newspaper was produced for sale—or at least it replicated the subscription information from the newspapers it imitated. But in neither case did the creators think that the audience for their works would include readers in a library in Michigan 150 years in the future.

The James Stephens case, featured in “Haydock’s Monthly,” was notorious in its time, involving the poisoning of Stephens’ wife, the assault of her niece, a revenge shooting by the victim’s nephew, and Stephens’ escape and re-capture—all elements sure to appeal to an active and enterprising lad. “Haydock’s Monthly” is part of the James V. Medler Crime Collection.

When I think about scale—about smallness—in the Clements collections, it is these moments of privacy that come to mind first, often because they are the most moving to me. In early August a new daguerreotype arrived at the library that took my breath away, precisely because the moment it captured was so tiny, so private. A white child of perhaps two or three years of age posed for a photograph. But instead of the “hidden mother” method, where a child’s mother would hold a child still for a photographer while concealed under a covering, this child is being comforted in a more visible, yet more private way. From outside of the picture’s frame on the child’s right, a hand of an otherwise unseen African American person gently holds the child’s hand in reassurance. We don’t know who the child is, nor do we know where the daguerreotype was made. We also don’t know who was offering their hand to comfort that child. Was it a hired nanny? A person enslaved by the child’s family? An employee of the photographer? We’ll likely never know. But that extended calming hand—a moment so brief that if you blink you’ll miss it—is the kind of small, quiet moment that close attention to the items in the Clements collections can reveal. Sometimes, tiny things mean the most.

Cramped, Crabbed, and Micro-Calligraphic

Cheney Schopieray

Curator of Manuscripts

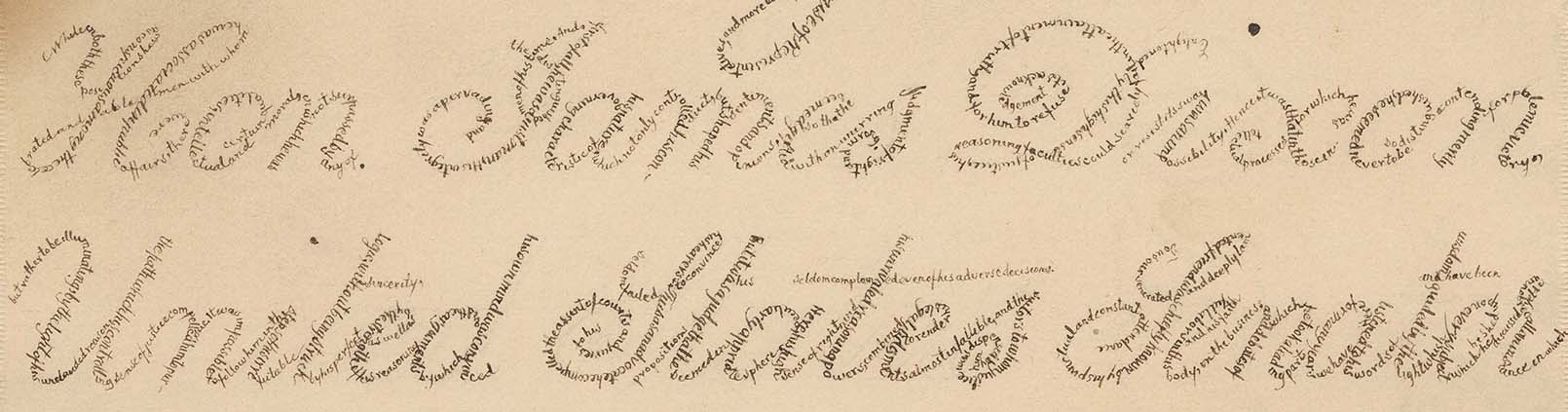

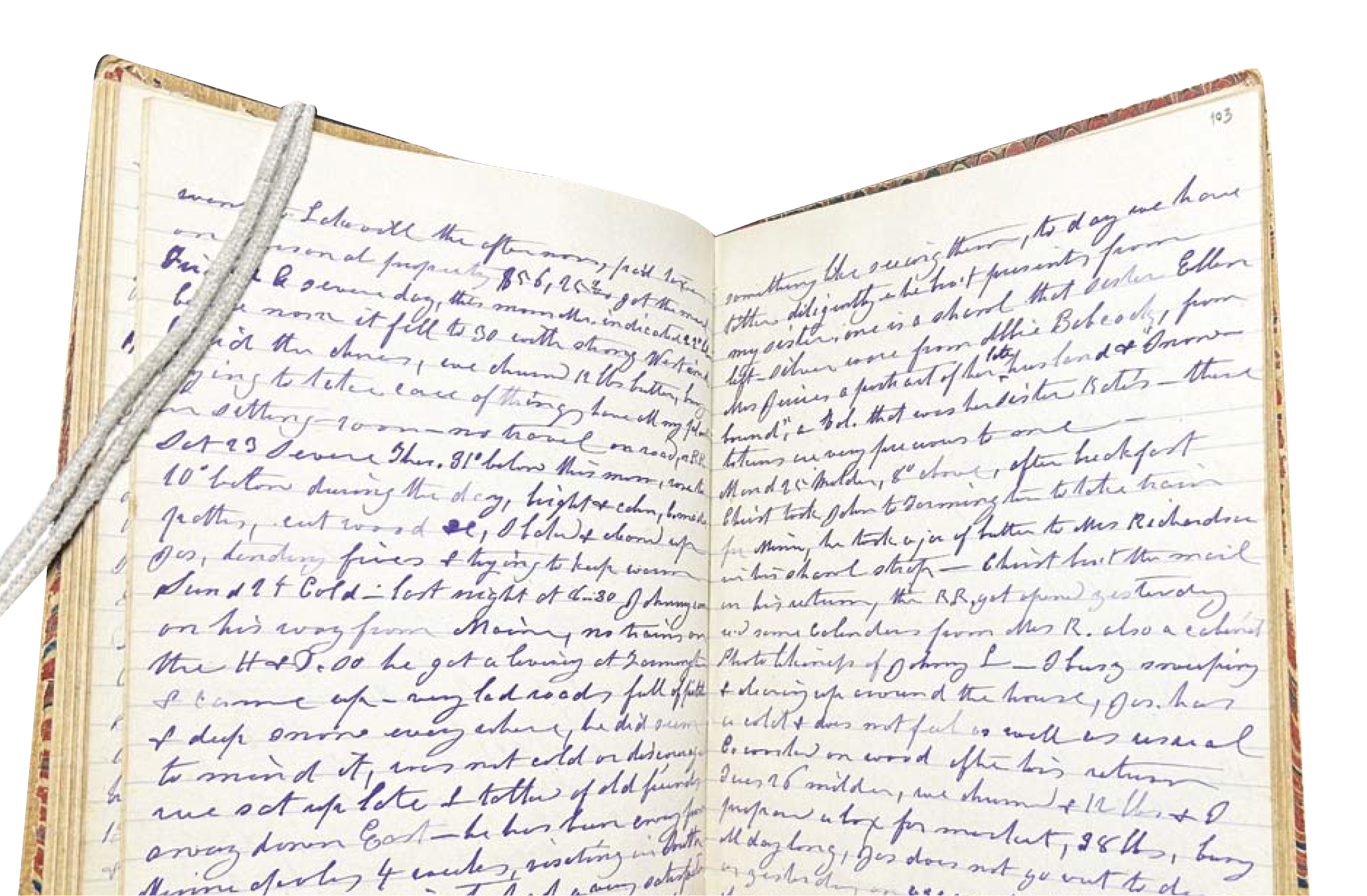

Rebecca Dodge Eaton’s handwriting diminished in size from a moonlit base-to-waist height of over 3mm, to her average typical height of ~2mm, to a cramped 0.5–1mm height.

Teacher and poet Rebecca Dodge Eaton (1796–1852) sat down to her diary in the night hours of July 30–31, 1839, to the sound of the waterfalls in Rochester, New York. She had been experiencing “not very fine feelings” alone in the boarding house where she lived, but this night she found inspiration in the glowing light of the moon. Thanks to its reflection, she could see just well enough to write out feelings and religious praises into a blank book that she filled with diary entries, poetry, and miscellany. Still, her desk was steeped in shadow and her writing became shaky and almost twice as large as usual. Over the ensuing 26 days, she diarized on the same page, recording visits to the library, buying a “philopaena” gift, purchasing books for herself, reading, and attending lectures. Since she previously filled the reverse side of the page with poetry, she wrote smaller and smaller as she attempted to squeeze in as much writing as possible to put off the inevitable need to continue her diary somewhere else in the journal.

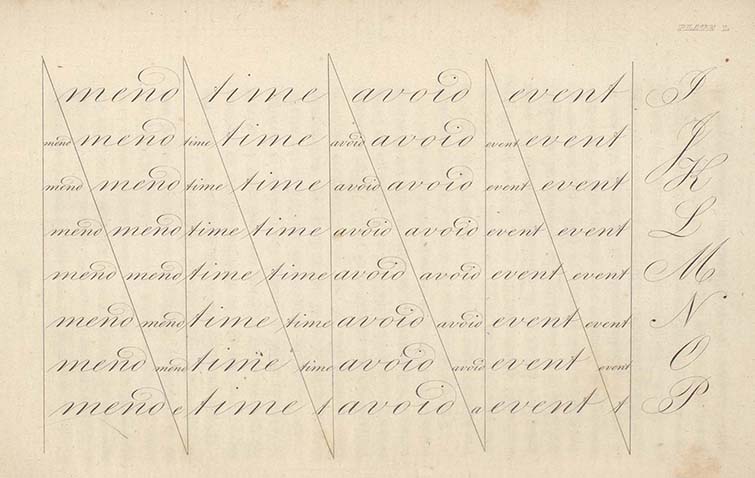

The influential Foster’s System of Penmanship (Boston, 1835) outlined a model for teaching students to write quickly, legibly, and with few frills. This plate shows teachers a method for using connected vertical and parallel lines for practice writing the same words in varying sizes.

Many overlapping reasons contribute to the size of a person’s handwriting. It may depend on the environment in which they write, their education and practice, their anatomy and physiology, the available writing utensils and surfaces, the purpose of the writing, and the intended audience. Viewing small handwriting seems to lead us naturally into asking usual questions of analysis: who made this? how did they make it? for whom? where, when, and why? Rebecca Eaton did not set out to write in an enlarged or a cramped script. Her handwriting changed size because of the presence/absence of light in her writing space and how she chose to keep her book—by adding text to seemingly random middle pages rather than sequential ones.

Penmanship education of the 19th and 20th centuries frequently included practices intended to hone students’ skills at writing letters and words with different forms, proportions, and spacing. Typically, younger children were (and still are!) taught to write large and only after gaining proficiency write smaller and smaller. Penmanship instructor Benjamin Franklin Foster (ca. 1803–1859) suggested a practice that moved from large hand to half text to small hand.

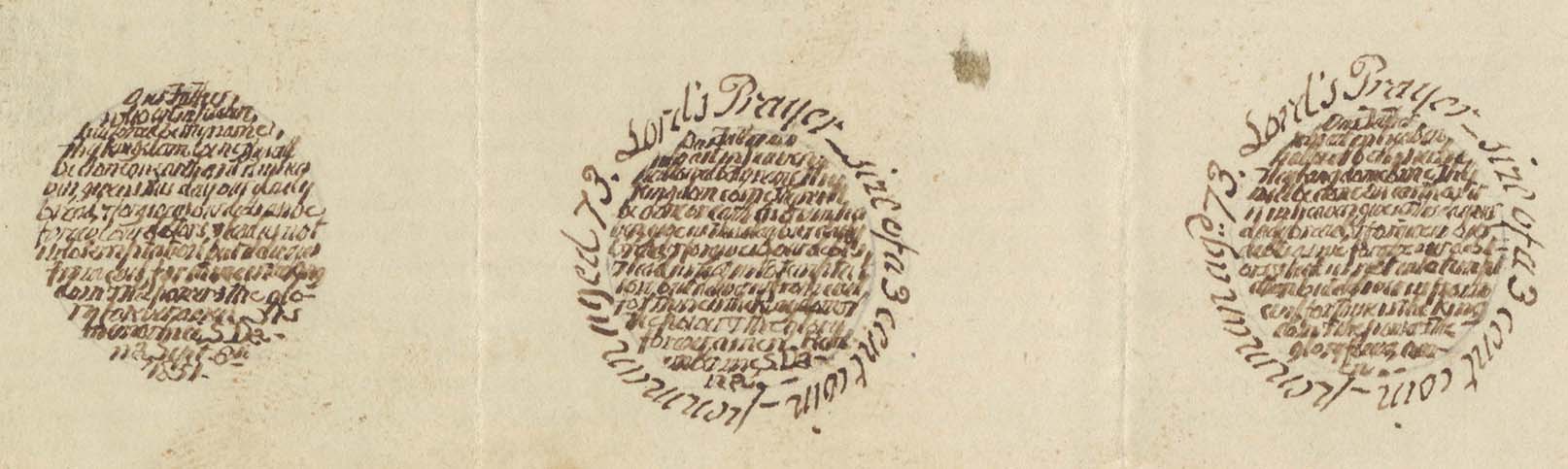

Magnification of these handwritten copies of the Lord’s Prayer reveals tracings of a coin used as a guide for the boundaries of the text. While vision typically diminishes with age, septuagenarian Rev. Samuel Dana defied the odds by producing legible writing with base-to-waist heights as small as 0.25 mm!

Some writers developed a habit or style of writing in a miniature hand as part of their everyday practice. Rev. Samuel Dana (1778–1864) of the Old North Church in Marblehead, Massachusetts, had famously small handwriting that he would use in his private writings as well as in service of his ministry. One of his routines was to take half dimes or three-cent coins, trace them with pencil, write the complete Lord’s Prayer in ink within the boundaries, erase the pencil, and give the results to friends or parishioners as keepsakes. The Clements Library has an example of three uncut, apparently undistributed examples that he created on September 6, 1851, at the age of 73!

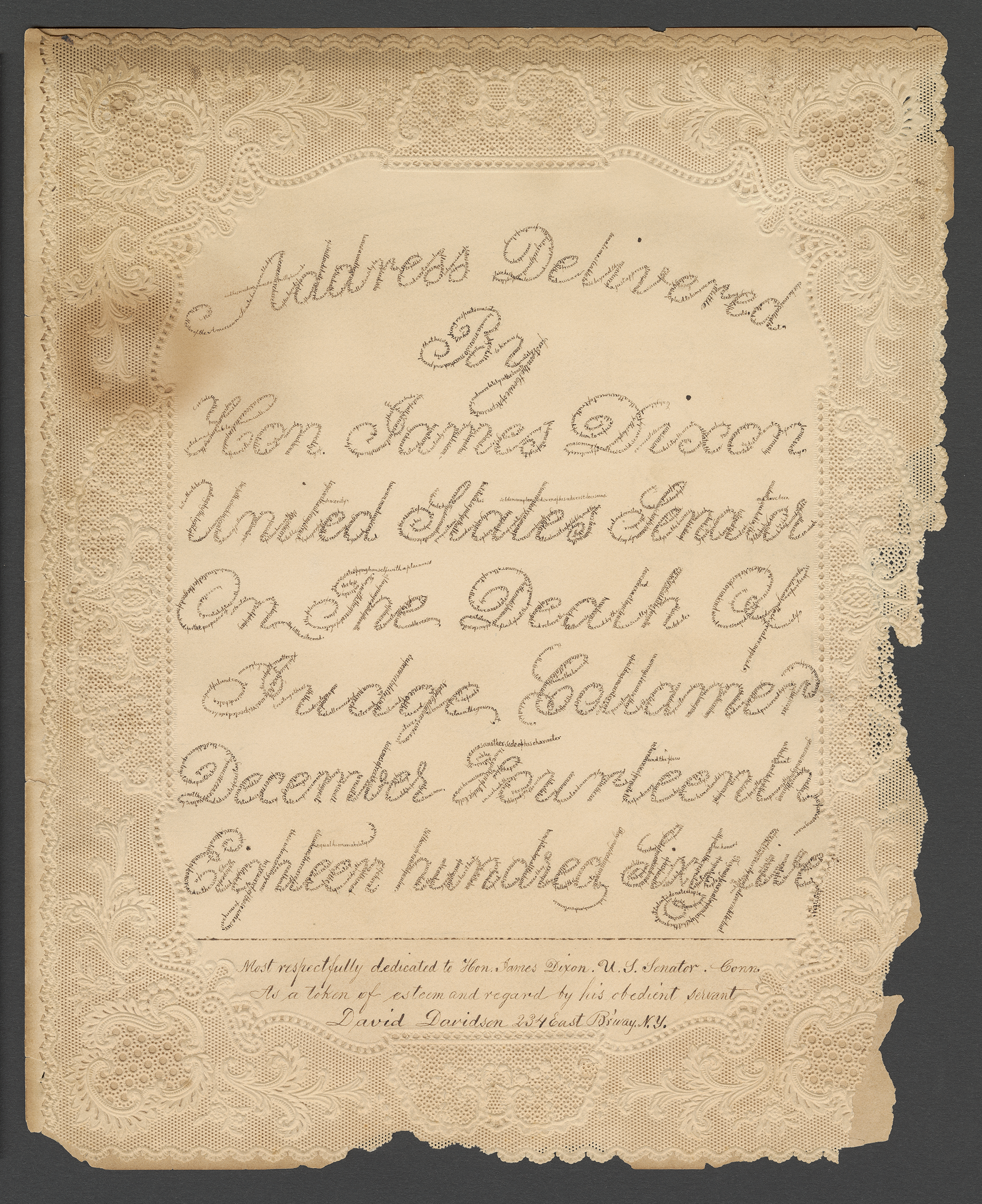

Micro-calligraphic writing might also have commercial motivations. The practice, skill, and talent of penmanship master and printmaker David Davidson is revealed in one example of his work. On ornate lace paper he utilized a “crow quill” steel pen nib to make a gift for U.S. Senator James Dixon, in recognition of his “Address Delivered . . . On The Death Of Judge Collamer” on December 14, 1865. When magnified, readers can see that title letters are comprised of the text of the speech. Davidson made a number of these works of art, which displayed his prowess to friends and potential penmanship students alike.

Micrography is a Jewish art form dating back to medieval times, using miniscule script to create shapes or drawings. Practitioner David Davidson, who referred to himself as an “artist in penmanship,” was born in Russian Poland and immigrated to New York in 1851. Other examples of his work include a micrographic drawing of the Astor Library and two portraits created using text from the Bible.

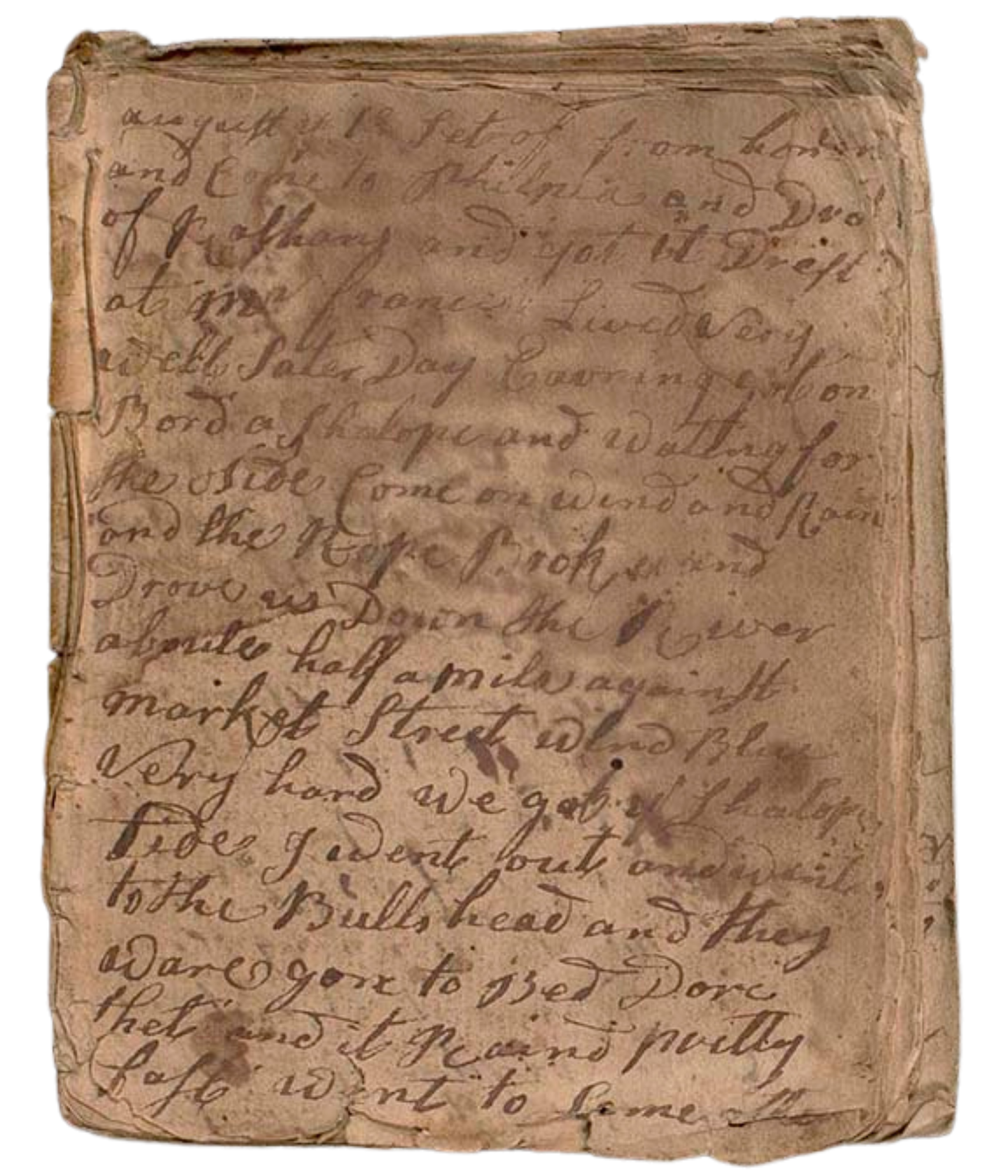

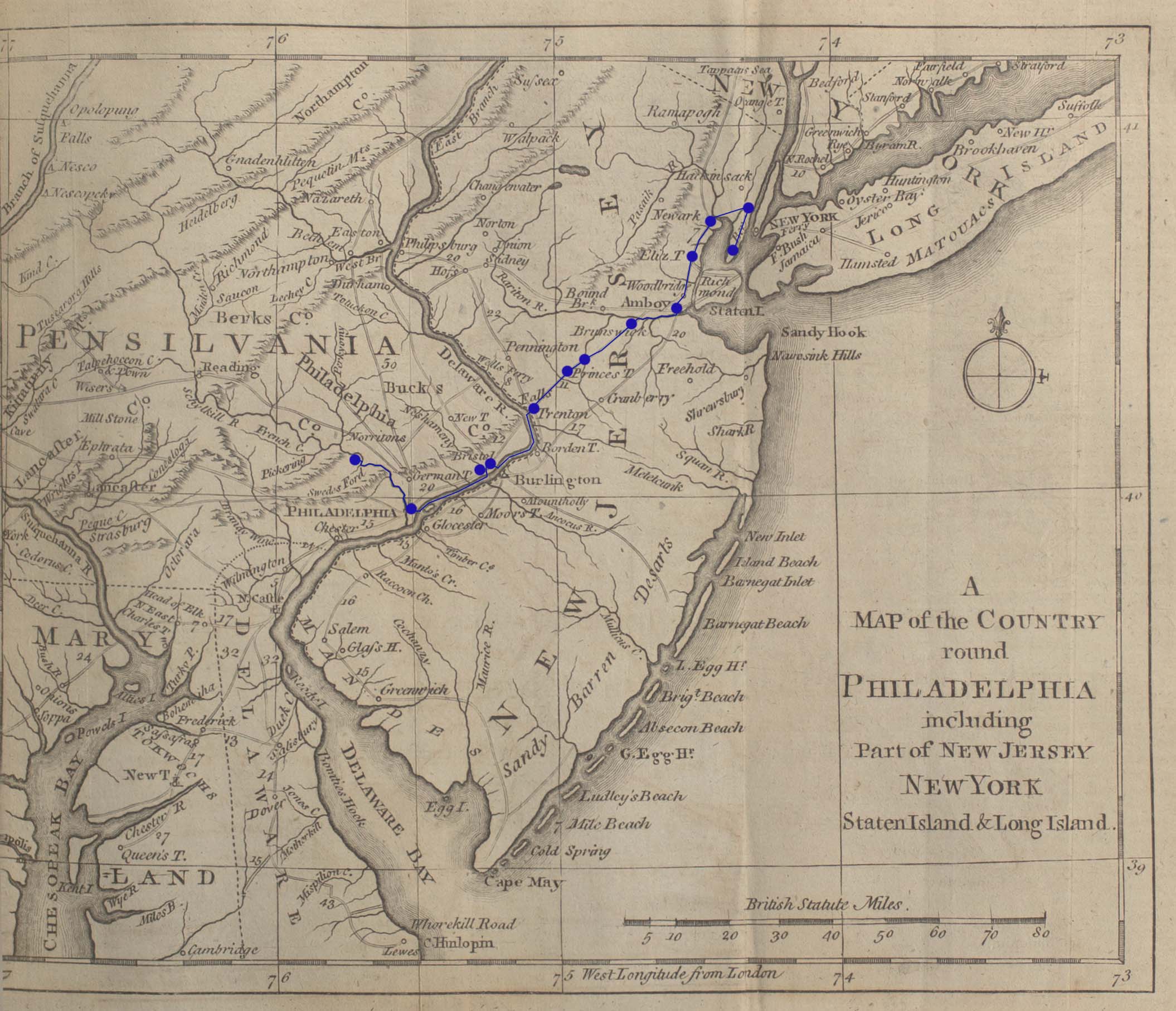

Tiny handwriting is perhaps most prevalent in pocket diaries and pocketsized notebooks, the sort which travelers often used for their portability These little books are practical for a person on the move, but! Taking up one of these home-made or pre-printed volumes also steels a commitment to small script or lettering. In 2020, Richard King Thomas donated his ancestor’s simultaneously diminutive and grand American Revolutionary War diary. The penman was a member of the Davis family of Upper Merion, Pennsylvania, a community roughly 15 miles northwest of Philadelphia. Though his identity is not yet known, the diarist was one of the men recruited for military service between June and August 1776 to assist in the defense of New York.

Extensive research has uncovered much information relating to this journal kept by a Pennsylvania militia member, but not yet his exact identity. The item is currently known as the Davis Revolutionary War Diary.

Davis was a militiaman or associator who took up a 10 × 8 cm hand-sewn volume of 34 pages and marched from his family farm on August 13, 1776. His handwriting is crabbed, a sort of cramped writing that is particularly challenging to read because of irregular character formation. With characters averaging ~1 mm base-to-waist height, the writer was able to fit as many as 20 lines on a page. His phonetic spelling adds to the importance of this documentation of his experiences. Davis carried the diary as he boarded a shallop in Philadelphia on August 17, 1776. That day, it survived the wind, pouring rain, high tide, and broken ship tie rope that stymied the departure and it stayed with him in a hayloft that night.

As he marched and sailed toward the City of New York, Davis kept hauling out his quill and a portable inkwell, writing on the most suitable hard surfaces he could find. He chose a large tombstone in an Elizabeth Town cemetery to write on as he passed through. Davis arrived at Bergen, New Jersey, the day after George Washington’s retreat from Brooklyn on August 30, 1776. Through the first two weeks of September, he moved with his battalion along the New Jersey shoreline, where he could see the British troops at work on Staten Island and hear the guns as they pressed in on Washington’s headquarters at New York. There, while moving between Bergen, Paulus Hook, and Bergen Point, Davis wrote about the oppressive mosquitoes, knee-deep mud, skirmishes between British Men-of-War and revolutionaries’ row galley boats, a woman who spared room for lodging, the sermons he heard, and his shifting diet (of chocolate, boiled beef, dumplings, bread, butter, pigeons, squirrels, and sugar).

Cramped, crabbed, micro-calligraphic, and just plain miniature handwriting can be a challenge to read and at times frustratingly opaque to the reader. It can also be awe-inspiring and beautiful. Or both at the same time. Asking “Why does Rebecca Eaton’s writing start large and then get smaller?” leads to thoughts about the space and conditions in which she wrote, as well as about her decision to use the blank book as she did. Saying “Wow!” and then asking, “Why would Samuel Dana make those little coin-sized prayers?” makes us think about Rev. Dana’s skills, motivations, and recipients. The stunning work of David Davidson draws us into questions about his practice, writing instruments, and audience. And considering the diary of American Revolutionary soldier Davis reminds us that the choice of writing surface may determine how small we have to write, whether we would prefer it or not.

Between August 17 and 21, 1776, Davis traveled with his diary from Philadelphia to Trenton; marched 26 miles or so through Prince own (Princeton), King’s own, and Brunswick; and then took the Raritan River to Amboy. A few days later, his unit moved to Elizabethtown, then Newark and Bergen. Between August 31 and September 12, Davis moved back and forth between Bergen, Paulus Hook, and Bergen Point. He then followed the same route home to Upper Merion, Pennsylvania, arriving there September 17, 1776.

On Pins and Needles

Jayne Ptolemy

Associate Curator of Manuscripts

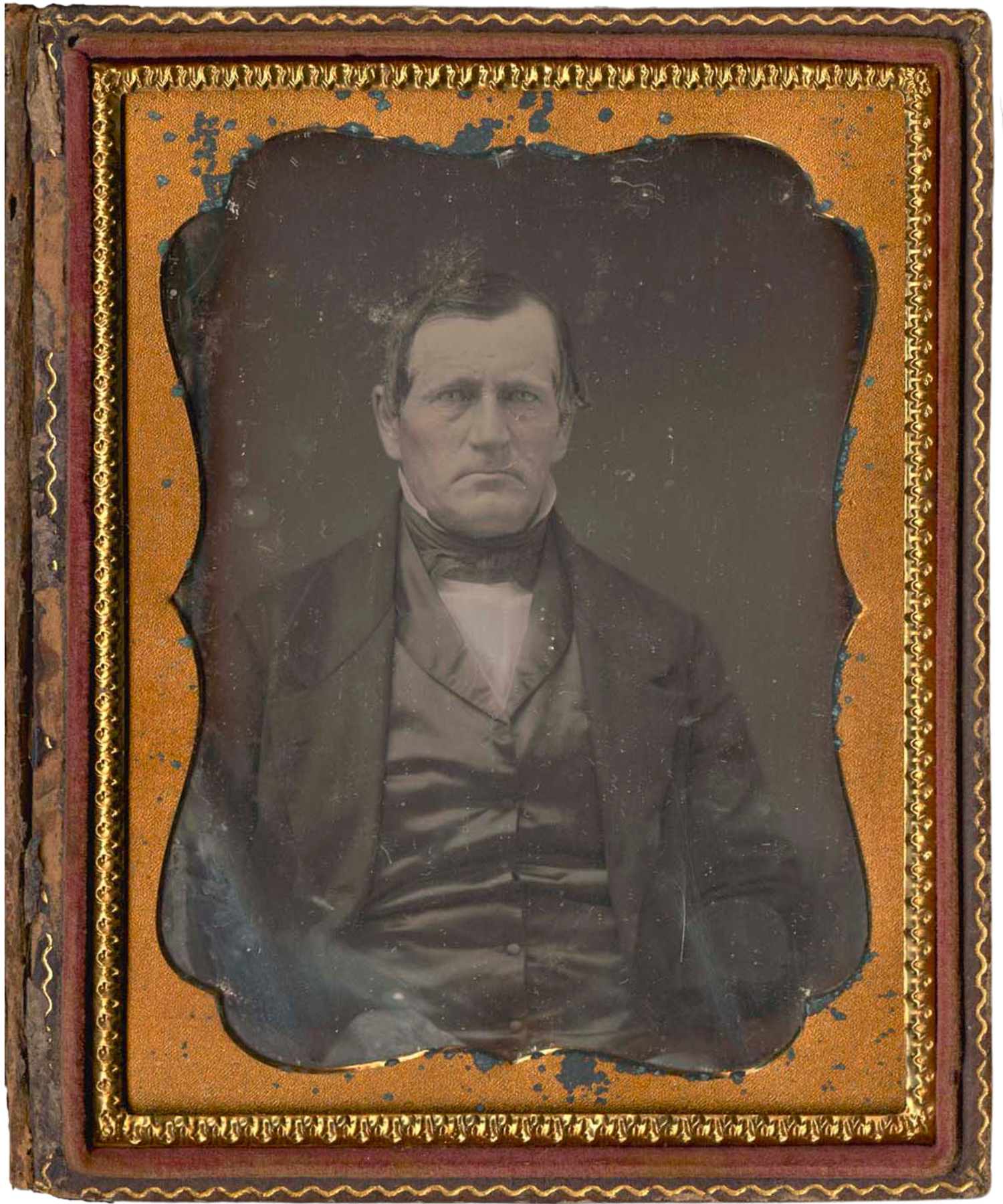

Bah humbug! A quick perusal of daguerreotypes will yield any number of severe-looking portraits that hide any sense of humor the subjects might have possessed.

Above, left: [Older man], by Moses Sutton, daguerreotype. Detroit: [approximately 1851 to 1857]. David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. The majority portion donated by David B. Walters in honor of Harold L. Walters, UM class of 1947 and Marilyn S. Walters, UM class of 1950.

Above, right: [Young woman], daguerreotype. [Kalamazoo, Michigan?]: [approximately 1855 to 1860]. David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. The majority portion donated by David B. Walters in honor of Harold L. Walters, UM class of 1947 and Marilyn S. Walters, UM class of 1950.

The archetypical librarian has their hair severely styled, lips pursed, and a cranky “Shhhhh!” at the ready. But if you’ve spent any time amongst the staff at the Clements Library, you’ll know there’s far more chatter and laughter than shushing going on. Likewise, ask most people what they think of 18th- or 19th-century Americans, and they’ll likely describe some version of a dour, tight-laced party pooper. Black and white photographs often do little to dispel this myth.

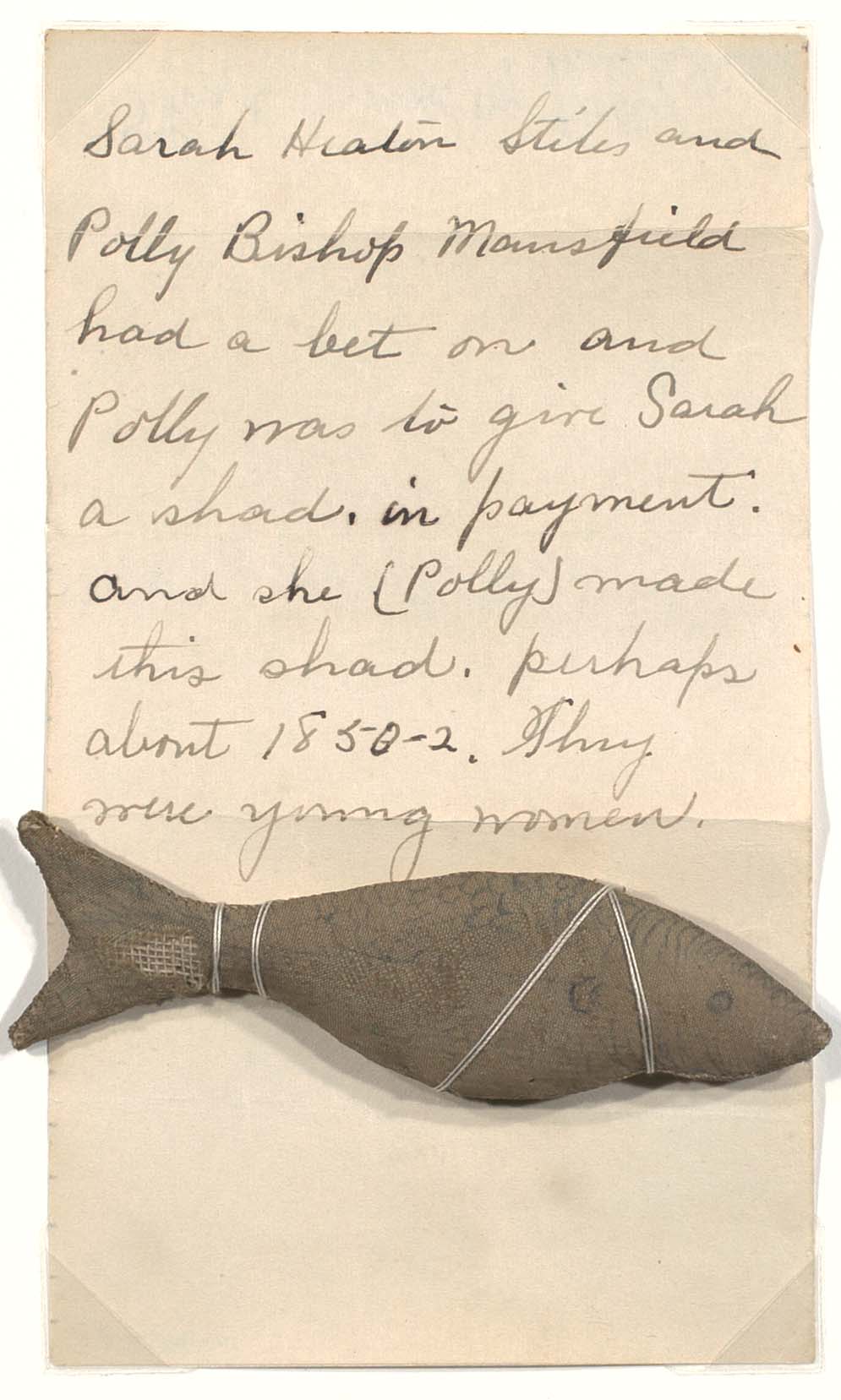

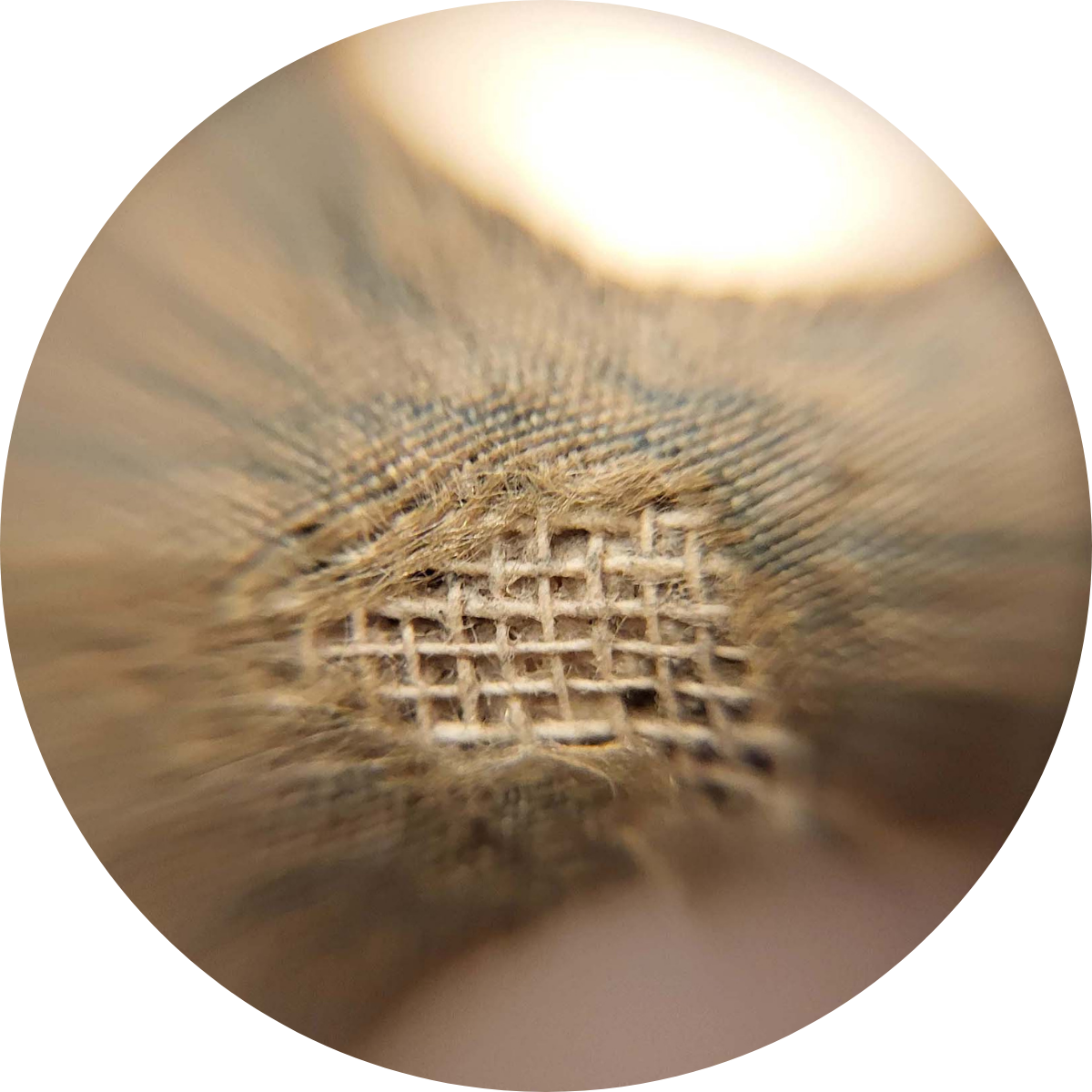

The note accompanying the shad, written at a later date, reads, “Sarah Heaton Stiles and Polly Bishop Mansfield had a bet on and Polly was to give Sarah a shad, in payment. And she (Polly) made this shad, perhaps about 1850–2. They were young women.” Polly C. Bishop Mansfield Collection.

Take, for example, these very traditional mid-19th century poems penned by a young Polly Bishop Mansfield on themes of friendship, remembrance, and perseverance. “Through all the changing scenes of life / Of sunshine or of sadness / Amid temptations, dangers, strife / Or in the hours of gladness / I ask one single boon from thee / My friend — wilt thou Remember me [?]”

While there’s a tenderness to the lines, there is admittedly also something rather anonymous about it. It feels like any number of young women might have written them, and you get little sense of Polly Bishop Mansfield as an actual person. If I’m being honest, I likely wouldn’t remember this on its own. It’s only the presence of a small, inside joke that elevates this collection to great heights. The poems, you see, are accompanied by a fish.

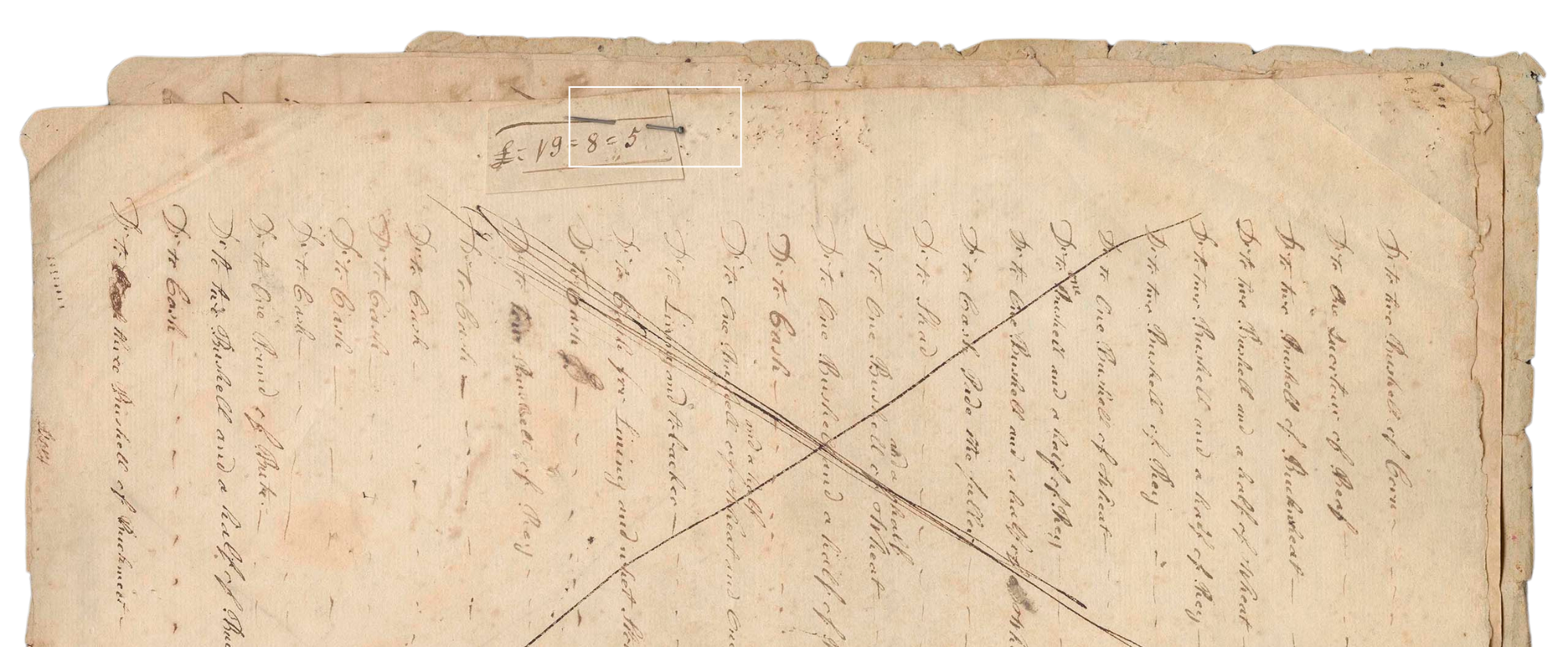

This little addendum was pinned into one of Anthony Wayne’s account books. Notice all the other pinholes in the margin, suggesting there were many others like it, in this age before Post-It notes.

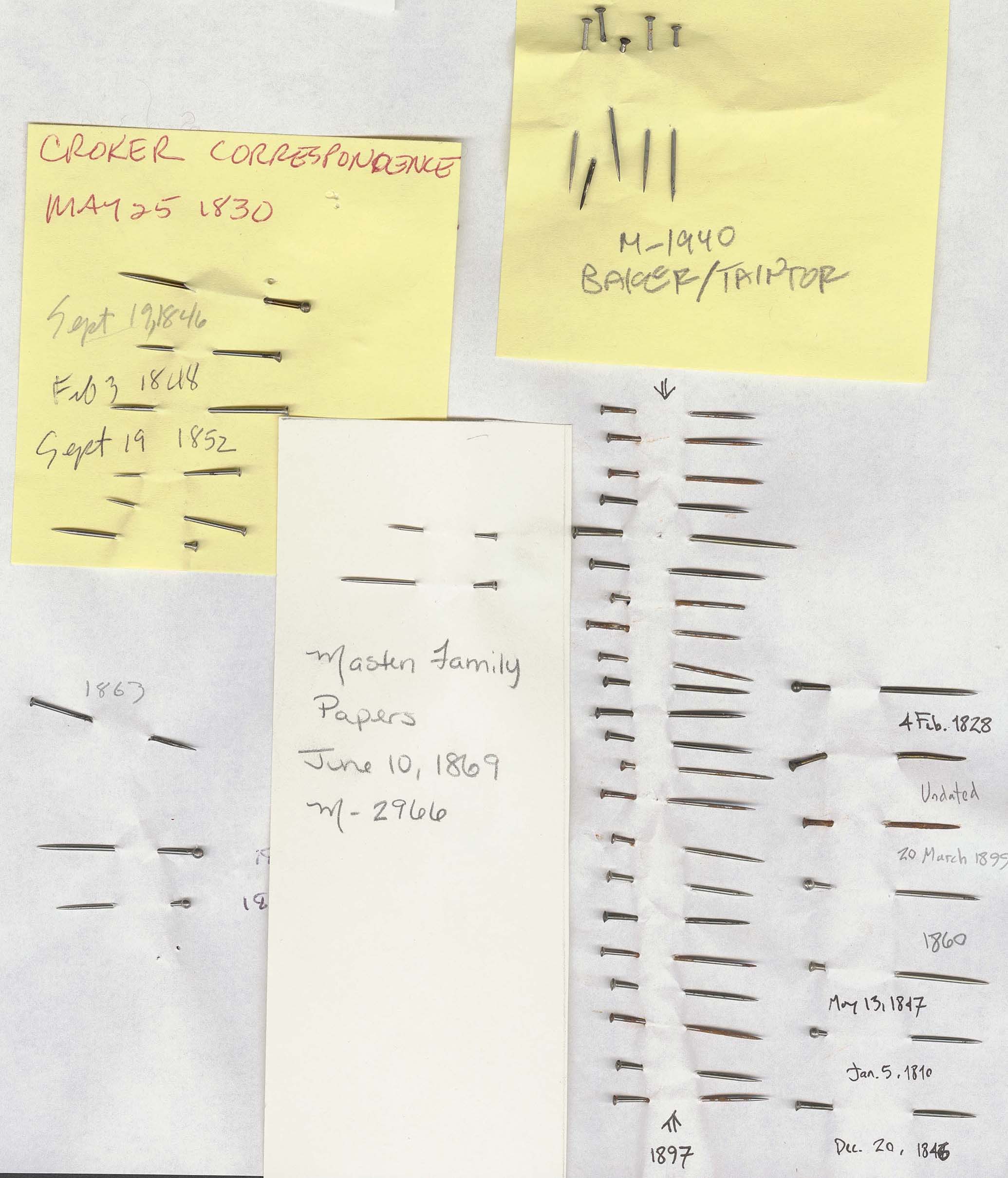

The collection of pins which were removed from documents throughout the Clements Library’s holdings for more than a decade remains uncataloged and still awaits a finding aid.

Morsels of History

Emi Hastings

Curator of Books

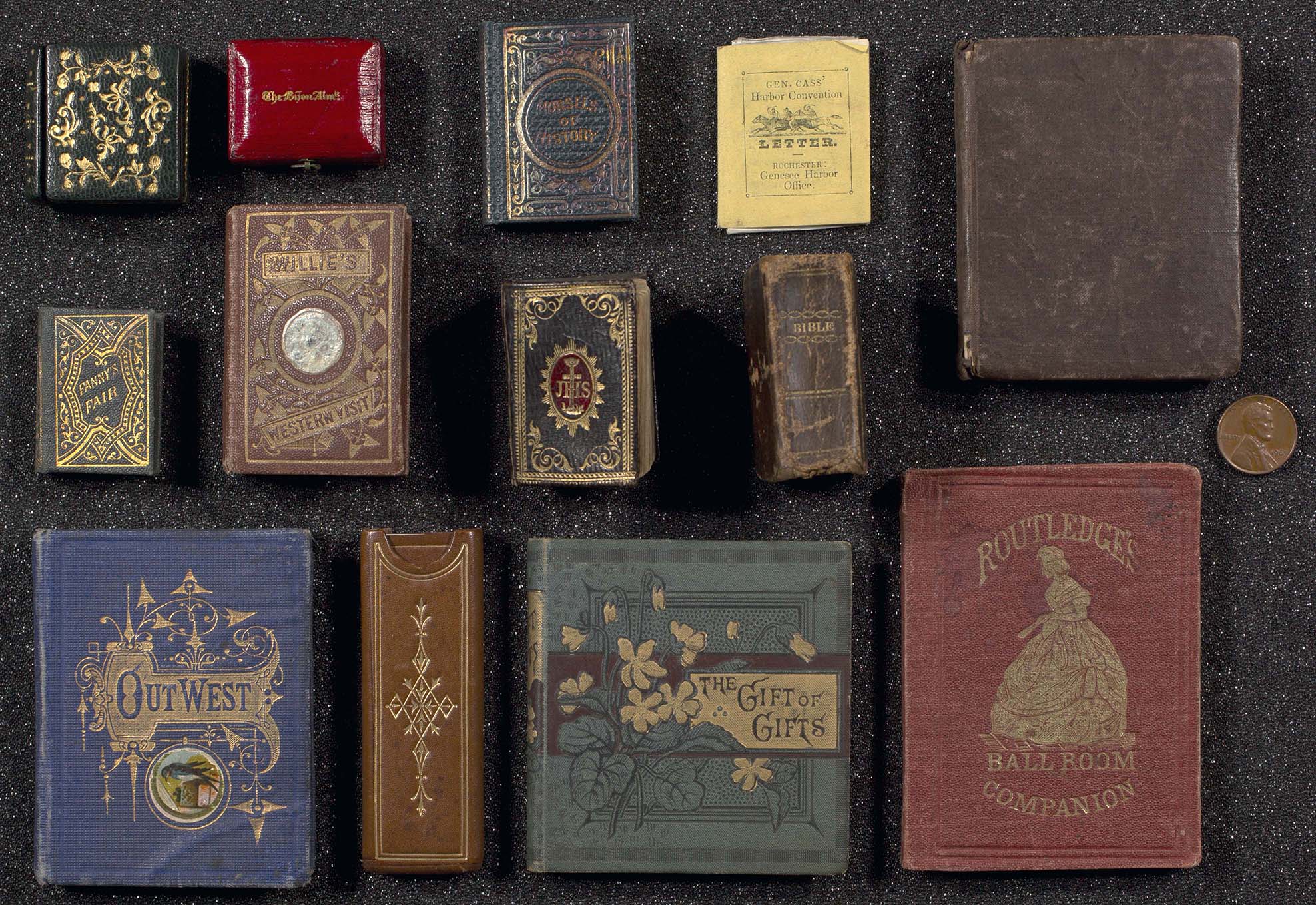

In a quest for the extraordinary, book collectors are often drawn to extremes. This may include the “first,” the rarest, and even the biggest or smallest of books. For the lover of small things, a tiny book has an enduring charm out of proportion to its diminutive size. A miniature book is often defined by collectors as 3 inches (7.6 cm) or under in all dimensions, although the Library of Congress allows miniatures to be up to 3.9 inches (10 cm) in height or width. What draws someone to a miniature version of a text, when a larger version may often be cheaper and easier to read?

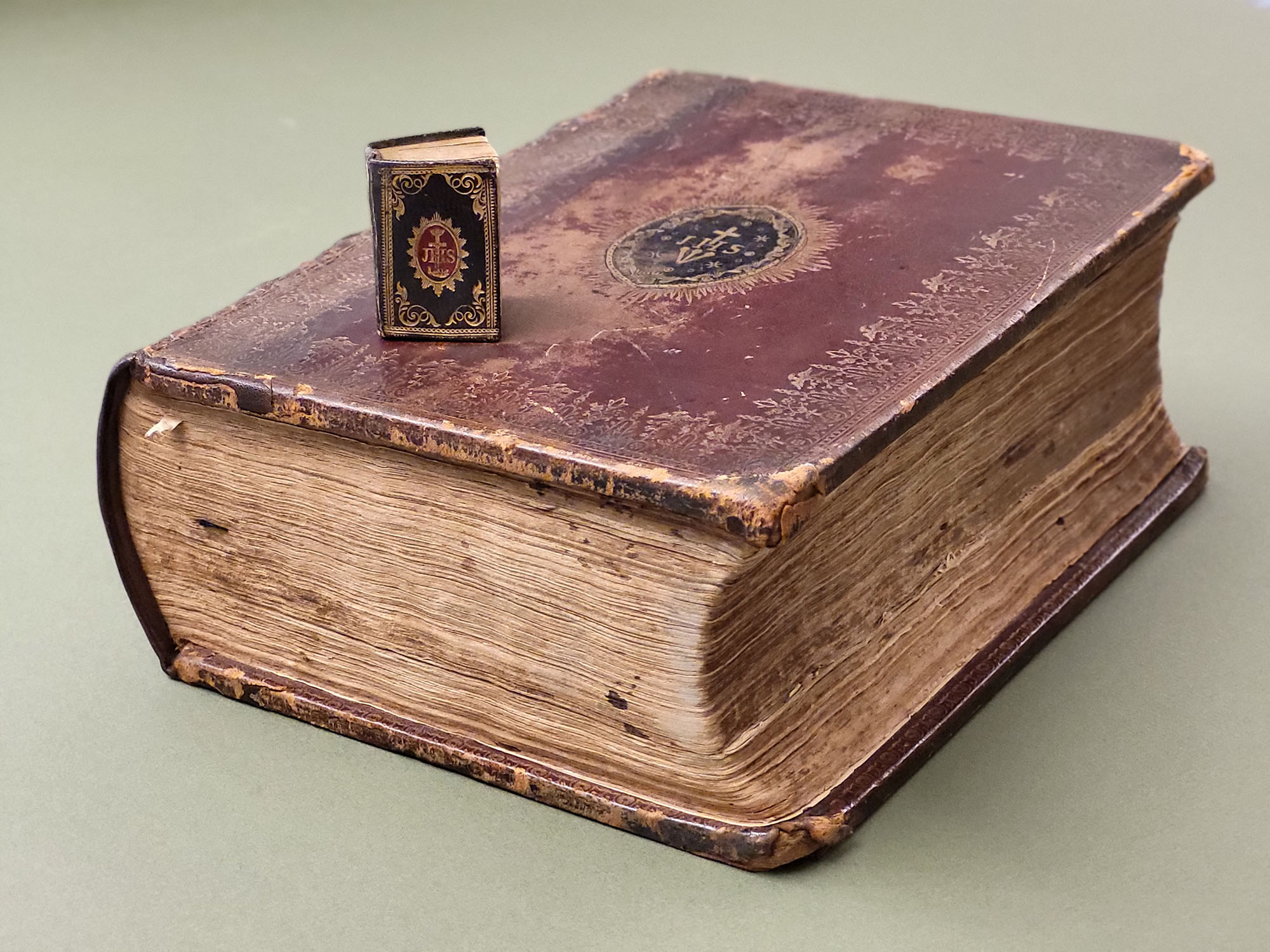

Many of the earliest printed miniature books were religious in nature, including such texts as Books of Hours, psalms, and Bibles. For these works, their miniature format served as a religious talisman or a personal reminder of faith, allowing the book to be kept close to one’s body. While the miniature text was still readable, turning the tiny pages required careful attention and focus, a kind of intimacy with the text that called attention to the physical format.

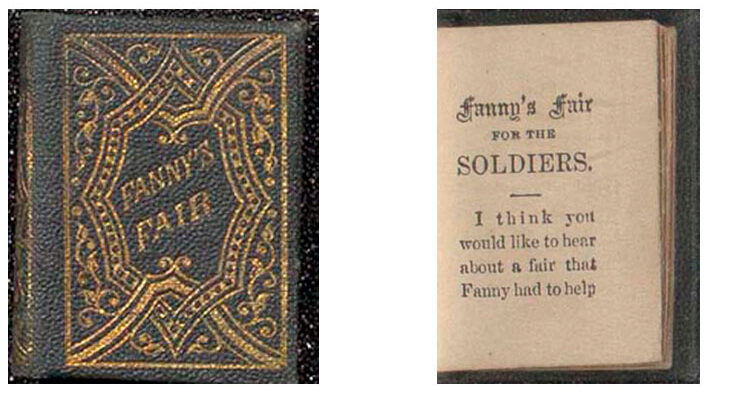

The “Aunt Fanny” of Fanny’s Fair (Buffalo, 1866) was Frances Dana Gage, a feminist and abolitionist who served during the Civil War as superintendent of Parris Island, a refuge for freed slaves in South Carolina.

Miniature Bibles, often called thumb Bibles, began in the 17th century in England and became especially popular in America in the 19th century. They contained a summarized version of the biblical text, sometimes with illustrations. While the first English thumb Bibles may have been intended for adult readers, later American editions were often specifically adapted for children. An edition of Bible History (New York, 1813; 5 cm) states in the preface, “It is hoped, the perusal of this little treatise will so attract the young mind, as to excite a curiosity and love for the scriptures at large.” The possession of a miniature Bible would thus lead the child to further study of the full-sized family Bible.

The Bible in Miniature (London, undated) bound in dark leather with decorative stamping in gold. An inscription on the flyleaf read “Mabel Smith from Papa.” Contrasted with a full-sized family Bible in a similar leather binding, The Holy Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments (Oxford, 1740) from the Weld-Grimké family papers.

The American Tract Society published numerous miniature books between 1825 and 1899, both for adults and children. Popular devotional works for adult readers included Dew-Drops (Philadelphia, 1884; 5.6 cm), A Threefold Cord (New York, 1953?; 8 cm) and Daily Food for Christians (Boston, between 1882 and 1900; 8 cm), all in multiple editions. The American Sunday-School Union in Philadelphia was also a prolific publisher of miniature books for children, including a popular book of prayers called Small Rain Upon the Tender Herb (Philadelphia, ca. 1835; 3.6 cm)

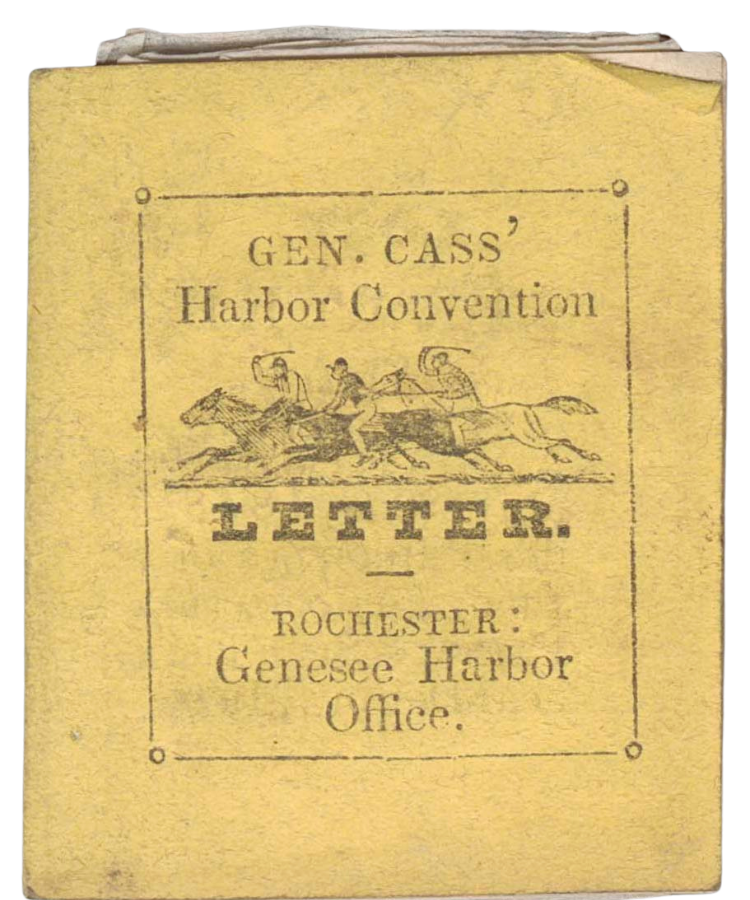

Schloss’s English Bijou Almanac for 1839 (London, 1838). Red leather slipcase with magnifying glass.

Gen. Cass’ Letter to the Harbor and River Convention (Rochester, 1848). Yellow pictorial printed wrappers, satirical advertisement on rear wrapper.

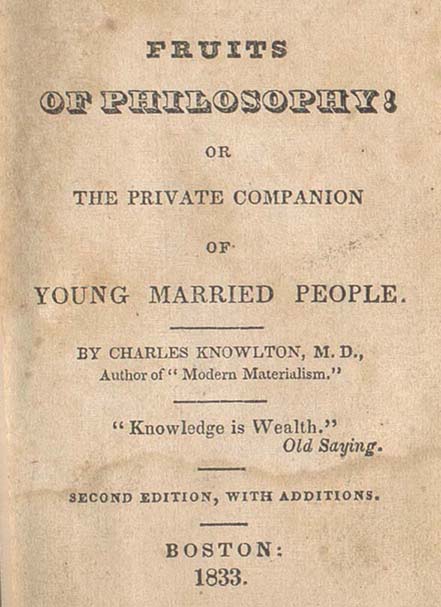

Charles Knowlton, Fruits of Philosophy, or, The Private Companion of Young Married People (Boston, 1833). Bound in plain brown publishers’ cloth.

Beyond their immediate appeal as adorably small objects, miniature books served a variety of purposes, ranging from the frivolous to the sacred. The miniature format made a religious text seem more personal or more appealing to young readers, transformed a plain volume into a tiny work of art, or made information easier to access on the go, whether you needed to look up an unfamiliar word, make a quick calculation, or read a favorite work of literature on the train. The lasting appeal of miniature books speaks to the many different audiences they have served and the ways in which they have been consumed by generations of readers.

Lilliputiana through a Lens: Secret Portals to Microscopic Worlds

Jakob Dopp

Graphics Division Cataloger

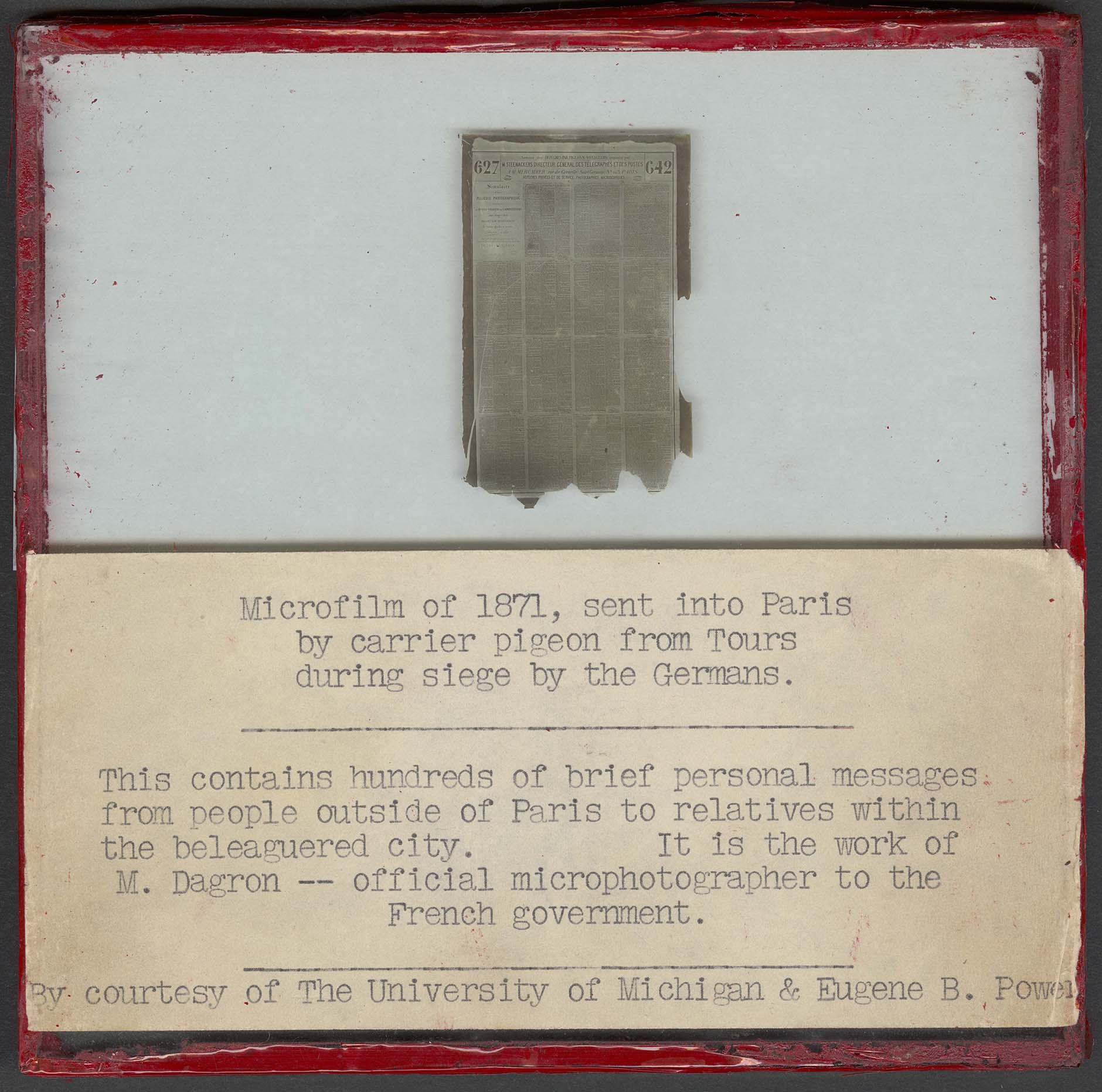

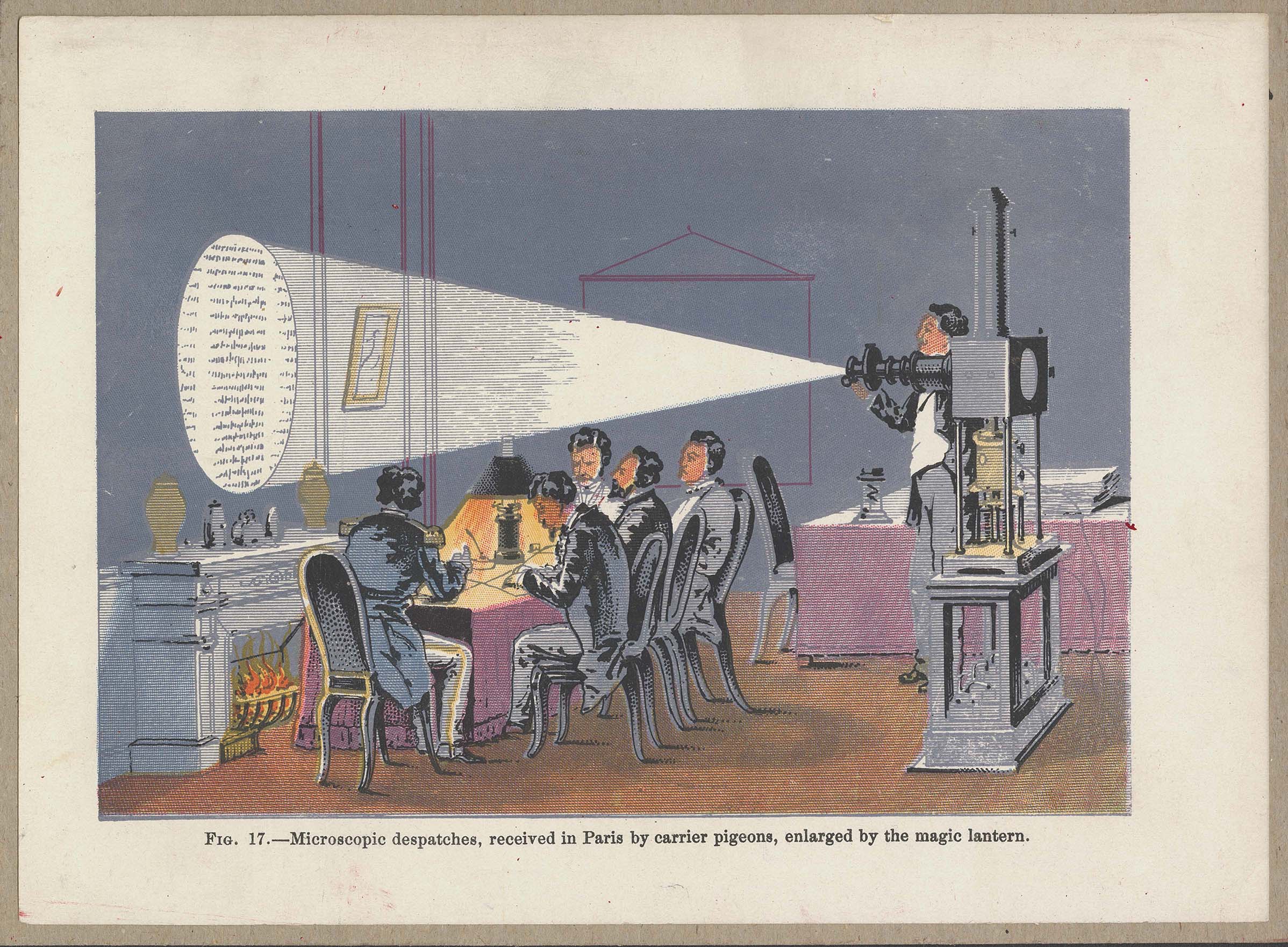

For instance, French photographer René Dagron ( 1819–1900) famously created microphotographs of secret messages and newspapers that were smuggled into Paris by carrier pigeons during the siege of 1870/71 in the Franco-Prussian War. After producing a microphoto, Dagron would carefully extract the exposed film, roll it up, and insert it into a small tube which could be discreetly attached to a pigeon. Upon receipt the microphotos could then be unrolled, placed back upon glass plates, and projected at an enlarged size via magic lantern for viewing. However, long before his involvement in clandestine military communications, Dagron had already established himself as the first person to recognize the lucrative commercial prospects of microphotography.

In 1944 the Clements Library received a set of materials related to Dagron’s Siege of Paris microphotography from University of Michigan alum Eugene B. Power (1905–1993). Power was the founder of University Microfilms International and is considered an important figure in microfilm publishing.

During the Siege of Paris in 1870, the German armies surrounded the city, preventing correspondence with the outer world. Microscopic dispatches flown in by carrier pigeon were viewed by news-starved residents via magic lantern, as depicted in this illustration from John Howard Appleton’s (1844–1930) Chemistry, Developed by Facts and Principles Drawn Chiefly from the Non-Metals (Providence, 1884).

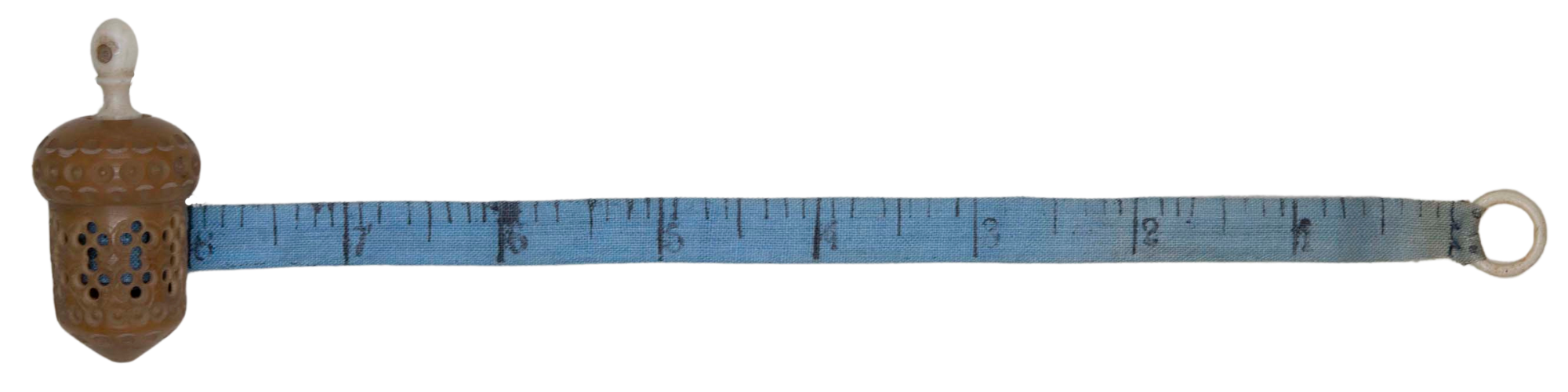

The term “stanhope” stems from Dagron’s ingenious use of an altered lens, a particular type of handheld magnifier created by Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Stanhope (1753–1816). After cutting down one side of a small stanhope lens to make a flat surface onto which a microphoto (often no larger than 2 × 2 mm) could be adhered, the lens could then be implanted inside of tiny holes bored into a vast array of objects including jewelry, pens, rings, scissors, pin cushions, pipes, children’s toys, ornaments, musical instruments, etc. Mass produced trinkets made from carved ivory such as miniature binoculars, telescopes, and eyeglasses were particularly popular objects. Common themes of microphotos found inside of stanhopes include landscape views, street scenes and city/town views, reproductions of famous artwork, major events (such as the World’s Columbian Exposition), and material that can best be described as salacious.

Three of the Clements Library’s stanhope viewers on display, with spools and a measuring tape for scale. The measuring tape itself is a stanhope viewer (from a private collection), note the light colored projection on the top which holds the lens.

The Clements Library has at least four examples of stanhopes that we are aware of (they are sometimes difficult to detect), although hopefully there are others hiding in plain sight that have yet to be found. An ivory letter opener/pen and miniature pair of binoculars containing views of Detroit and Mackinac Island both hail from the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography. The Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers contain a miniature ivory telescope with an image of Minnehaha Falls. Last but not least, we have also recently acquired a wooden knife stanhope manufactured as a tourist souvenir which contains views of Mt. Lookout, Tennessee.

The appeal of the stanhope as an entertaining novelty is obvious in that theoretically almost anything can be turned into one. Even the most unassuming everyday object could be bestowed with the magical power of conveying secret imagery. Bearing this in mind, you should always make sure to thoroughly examine any and all antique trinkets you come across as you never know what might happen to contain a secret portal to a microscopic world.

This image captures what is visible to the naked eye when peering through the stanhope lens—in this case the Minnehaha Falls. The microphotograph, itself likely no larger than 2 x 2 mm, may be magnified by a factor of 300 when viewed through the lens.

Eye of the Microbe

Maggie Vanderford

Librarian for Instruction and Engagement

The golden age of microbiology during the 1880s–90s signaled a landmark shift in popular awareness of human relationships to the microscopic world. As French chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) and German physician Robert Koch (1843–1910), among others, rapidly identified the bacteria responsible for infectious diseases like cholera and tuberculosis, such scientific discoveries quickly took hold of the public imagination. By the end of the century, the language of microorganisms was part of common public health parlance. It became a given that millions (or billions!) of tiny living creatures, unseen to the human eye, were in fact powerful players in battles with infection or epidemic disease. At the Clements Library alone, numerous medical treatises and manuscripts document this shift. The Thomas Nock Notebooks (1884–1890), for example, include the writings of a Philadelphia medical school student invested in the nuances of the “germ theory of inflammation.”

Despite the swift pace of microbacterial discoveries, there was still significant uncertainty about exactly which kinds (and how many?) of these small lives existed in this invisible realm. Such an immense world of uncategorizable minutiae required new terminology to describe it. The word “microbe,” coined by surgeon Charles-Emmanuel Sedillot (1804–1883) in 1878, was rooted in the Greek terminology for “small” (mikros) and “life” (bios). The concept of the “microbe” became a helpful blanket term with which to describe anything from bacteria to fungi to protozoa to yeasts or viruses. Still today, a microbe can describe any “very small living thing . . . that can only be seen with a microscope.”

The satisfying vagueness of the word “microbe” was useful for scientists who needed wiggle room in providing explanations of infectious phenomena, but even more useful for literary authors and psychologists inspired by the idea of a micro-world. Easier to conceptualize as a character than a million bacterium, microbes inspired a booming print culture of advertisements, treatises, and creative stories imagining the inner lives of microscopic beings.

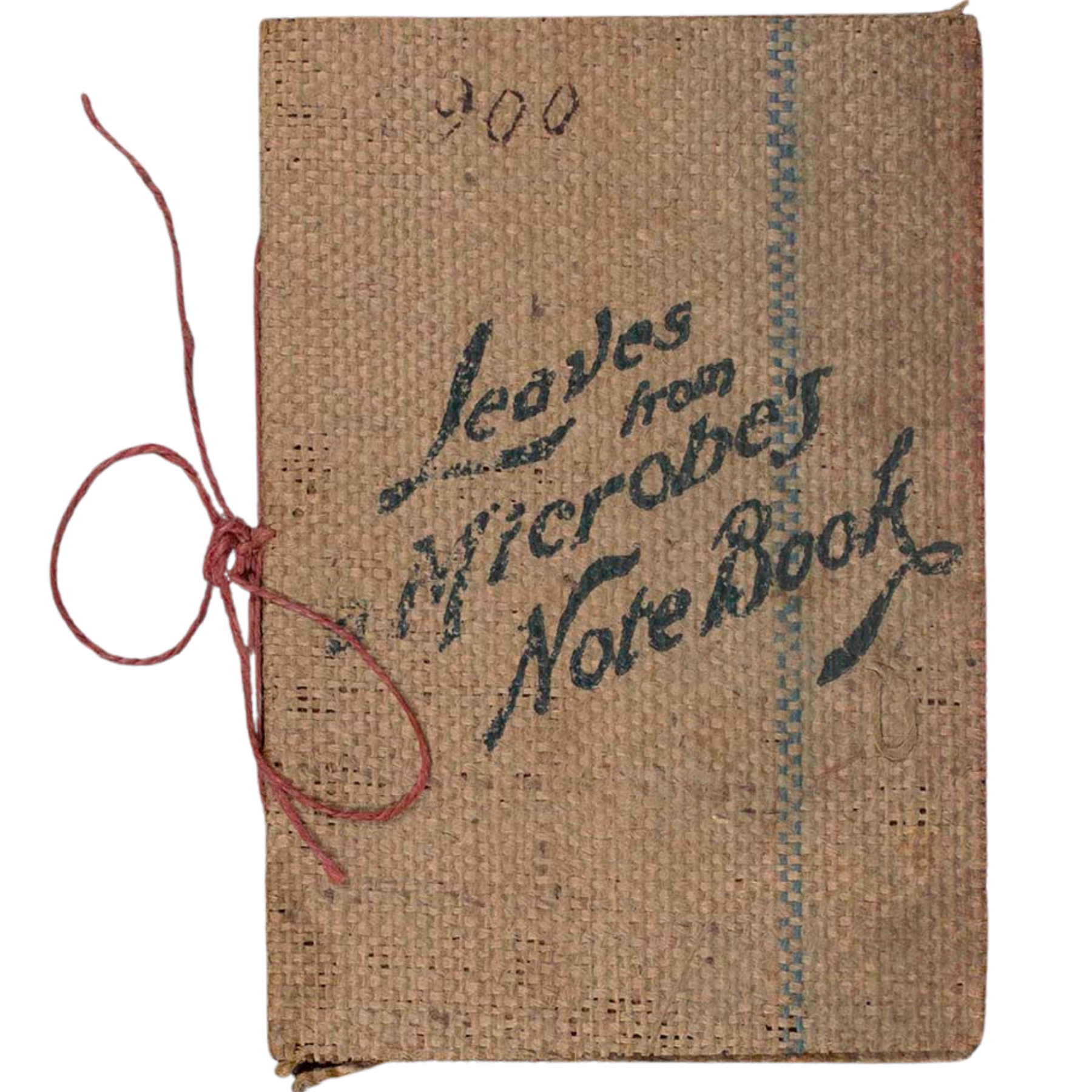

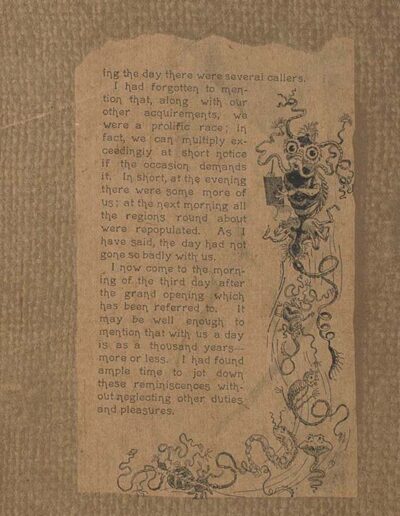

The Clements Library holds one particularly rare example of this print phenomenon, Leaves from a Microbe’s Notebook (Yonkers, 1890), which only exists in one other copy held at the Huntington Library. The striking pamphlet was bound in burlap fabric wrappers and printed on imitation burlap paper, an expensive proposition for what it was—which was a piece of promotional literature for the antiseptic Borolyptol, manufactured by the Palisade Manufacturing Company in Yonkers, New York. The story was narrated by a dramatic (and literarily inclined) microbe, who recounted the tale of his birth and of his role in the formation of a pus-generating abscess. Unfortunately for the microbe and his brethren, the doctor in the story sprayed the abscess with Borolyptol; although the first treatment was not enough to kill them, it had a traumatic effect: “Up to this time I had had a clear conscience and an unimpaired memory,” wrote the microbe. “Later in the day as my senses slowly returned, I became aware that something had happened. Gradually there came to me a recollection of a horrible, blinding, suffocating storm which had swept over us.”

An early 20th-century Borolyptol label indicated that it was “An Ideal Antiseptic and Germicidal Fluid for Internal and External use. Antagonistic to All Disease Breeding Germs.” Image courtesy of Lake Forest College in partnership with the Chicago History Museum.

As the story continued, the microbe shared other details about his “race”: they can multiply “exceedingly” at short notice if the occasion demands; their temporality clashes with human chronologies (“With us a day is as a thousand years—more or less”), and so on. The melodramatic ending felt reminiscent of a starlet’s stage soliloquy when the antiseptic returned for the final death blow, and the microbe described his own death: “Ah! It grows cold! My senses are leaving. It is the end; yet I shall die content. Vapors rise about me taking on fantastic shapes. As they twist and twirl and twine a symbolic word stands forth. Nerving myself, as the light fades out, for a final effort, I transcribe it as it reads–“Borolyptol.”

The humorous advertisement was, on one level, a silly and clever visualization for customers who wanted to believe that all infections had a singular, simple solution in the form of antiseptic. On another level, it seriously anticipated real questions that experimental psychologists would ask in the coming decades about the interior life of microbes. The Clements Library holds a copy of experimental psychologist Alfred Binet’s landmark text, The Psychic Life of Micro-Organisms (originally published in New York in 1889; WLCL copy from Chicago, 1897), which detailed the psychological phenomena witnessed in “the lowest classes of being.” Binet didn’t go as far as insisting that microbes thought about long walks on the beach or feeling pain, but remained certain that they experienced some kind of psychological interiority.

In addition to such psychological and philosophical inquiries, American authors such as Mark Twain (1835–1910) were deeply invested in imagining a microbial perspective as a narrative way to investigate human similarities to other creatures. After reading The Story of a Germ Life by H.W. Conn (New York, 1904), Twain began writing 3,000 Years Among the Microbes (1905), “Translated from the original Microbic,” a scientific fantasy novel narrated by a man-turned-cholera germ living among the microbes in a tramp’s body. For Twain, the viewpoint of a microbe helped investigate the ethical dilemmas at stake in sharing the world with an unknown, possibly unimaginable number of organisms, both macro and micro. Famously, Twain left his microbe novel unfinished. Something about the tension between the human and microscopic worlds felt irresolvable to him, and he certainly wouldn’t rely on the easy simplicity of killing them all off with an antiseptic à la Borolyptol.

Although fascination with the microbe, specifically, as a character, a form, and an idea may have emerged in 1878 with the word itself, a compulsion to narrate from the perspective of microbial life has remained throughout the twentieth century. From the Adventures of Jimmy Microbe by Virginia Budd Jacobsen (Chicago, 1937) to the Adventures of Micki Microbe by Maurine Burnham Guymon (1987), I Contain Multitudes, by Ed Yong (New York, 2016), and Me, Microbes, and I by Philip Bunting (Melbourne, Australia, 2021), it is clear that we remain more motivated than ever to not only understand the microscopic world, but to live within it.

This sampling of pages from Leaves from a Microbe’s Notebook features fanciful depictions of microscopic life forms.

“A Just and Perfect Inventory” in Miniature

By Iman Jamison

Manuscripts Division Intern

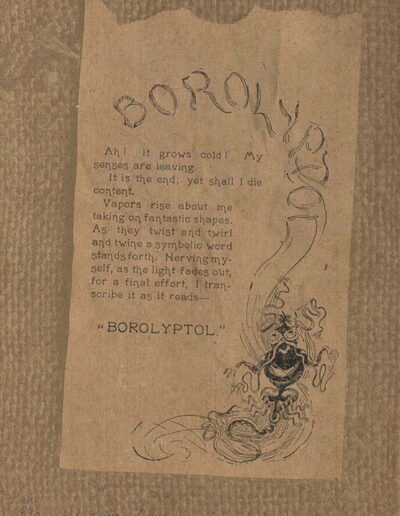

“Ms. Inventory of the Samson Adams estate, August 1792,” in the digital collection, Samson Adams Papers, 1767–1794.

The Clements Library houses thousands of records, ephemera, lists, and inventories that reveal the rare stories of lives lived long before us. As a recent history graduate, I am honored to have had the opportunity to gain glimpses into these stories, whether they be of a missionary traveler in the late 18th century or the 19th-century letters of an antislavery activist. However, out of my four years at the University of Michigan, one particular story comes to mind, woven together by “little pieces” of inventory.

During the Winter 2024 semester, I was a student in Matthew Spooner’s class, Silences of the Archives: Slavery and the American Revolution. While searching for archival records relating to African Americans, we often lose access to the humanity of those we are researching. The hands-on work we participated in at the Clements allowed my classmates and me an understanding of the missing pieces of the historical memory of African Americans during the Revolutionary War-era. To this end, we looked through the letters and records of the British anti-slavery advocates as well as the ephemera and manuscripts of Black Americans themselves.

During one class session, I was introduced to Samson Adams, a free African American of the late 18th century who resided in New Jersey and worked as a trader, carpenter, and laborer while taking care of those around him. He left a legacy of economic success and community, bequeathing his estate to his brother and sister as well as to the “Episcopal, Presbyterian and Methodist churches in Trenton” and “a small sum for the poor of the city.” The Samson Adams papers, which span 1767 to 1794, contain the estate and business documents for Adams’ time in Trenton, New Jersey, including the estate inventories drawn up following his death.

“A Just and Perfect Inventory of all and Singular the Good Chattles . . . of Samson Addams . . . taken and appraised this Day in August in the Year of our Lord Seventeen hundred and ninety two . . .” can be read at the top of one of these inventories. One can see a list of the objects from his home, organized by the rooms in which they were found. Items such as a flour barrel, bed bolster and pillows, spelling book, and a “Cracked Looking Glass” are just a few of the occupants of Adams’ back parlor.

As a class, we were tasked with reading these inventories and interpreting the significance of the document’s presence in the archive. However, Jayne Ptolemy, Associate Curator of Manuscripts, and Maggie Vanderford, Librarian for Instruction and Engagement, did not stop there. They presented us with the opportunity to not only read these inventories but engage with and visualize the life of Adams through tiny pieces of paper.

With our inventories in hand, we scoured a table filled with miniature paper cut-outs representing the objects present on the list—objects that lived in the rooms of Adams’ dwelling. One by one we found each item on the inventory and its corresponding cut-out and recreated what we imagined his back parlor and bedroom may have looked like. We were asked questions about how we thought his rooms might have been organized: Was there a reason the cracked looking glass is followed by a pillowcase on the inventory for a room supposedly used for the reception of guests? Why was there a spinning wheel in Adams’ bedroom? What was the significance to how he stored his belongings or is the significance lost simply because of how the author of the inventory chose to order them?

The small rooms we created presented us, as historians-in-training, with a way of envisioning the life of Samson Adams, highlighting the silences so often present in African American history. These seemingly mundane lists and inventories are the exact artifacts of history that help answer our questions, and also leave us with new mysteries. The tiny replicas of his estate were instrumental in that process. I will always wonder if the images on our little pieces of paper truly resembled the objects scattered around the rooms of Adams’ estate, a visualization of the legacy of a free African American man building economic gains when the odds were very much against him.

The internet was scoured by Clements staff to locate representative images of items listed in the Samson Adams inventories.

“1 Bed spread Patchd work Bed and Sundry Cloths on it Bedstead &c” (Bed, Object Number 1981.0010, Winterthur Museum Collections)

“Two flower Barrels & C[ontents?]” (Wooden Flour Barrel, Warwickshire County Museums)

“Bellows” (Bellows, Object umber 1957.0787, Winterthur Museum Collections)

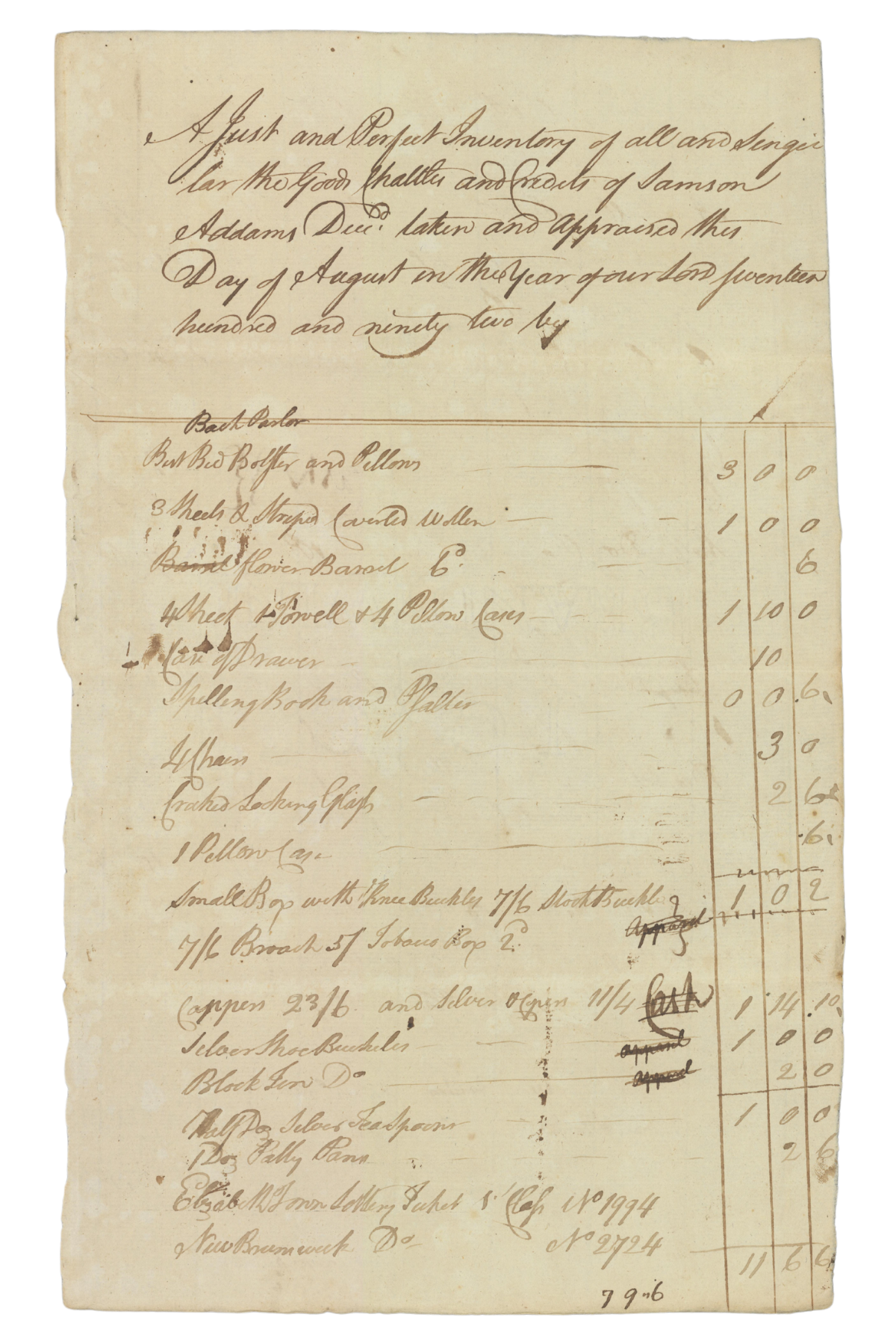

A Plan for Your Pocket

Sierra Laddusaw

Curator of Maps & Graphics

The Matthews-Northrup firm rose to prominence as the publishers and printers of railroad maps, which required a level of detail also demonstrated in their Map of the United States.

When prompted to think about “tiny things,” maps may not be the first objects that come to mind. However, I invite you to think about how you use maps on, possibly, a daily basis: through the phone in your pocket. We use map applications on our phones for guidance when driving and navigating unfamiliar cities, as a reference on how to get from point A to B, and to decide on the closest place to grab lunch. A convenient map in your pocket isn’t a new idea; today’s digital maps are modern technology’s answer to the pocket maps of the past.

In the United States, pocket maps were first retailed to the public in the 1820s. Major American map publishers, including Samuel Augustus Mitchell (1792–1868), Henry Schenk Tanner (1786–1858), and Anthony Finley (1784–1836), produced pocket maps that highlighted the growing road and railroad networks. Pocket maps of the 19th century were printed and folded into slipcases or covers made of thick paper, cardboard, and—for deluxe printings—leather. The map itself was typically printed on paper, though sometimes the map would be mounted on linen to help reduce the wear and tear of regularly folding and unfolding the paper. Pocket maps were designed to be disposable, with publishers regularly releasing updated editions.

The smallest pocket map at the library, when folded into its cover, measures 13.2 × 5.8 cm. Map of the United States, published by the Matthews, Northrup, & Co. in 1891, is a vest pocket map showing the boundaries between the states, location of cities, and the routes of major transportation networks. Alongside a brief history of the country, the back of the map is printed with a variety of quick facts, including a list of past Presidents and Vice Presidents, military statistics, and a list of “Fifty Famous Americans.” The publisher also makes good use of the cover to advertise their “handsomer,” “handier,” and “always up to date” maps of every state, offered for sale at fifty cents a map!

Developments, Events & Staff News

Angela Oonk

Director of Development

I’ve been thinking about the staff discussions around the topic of this Quarto and how excited everyone became when we agreed upon “tiny things” from the collection. There were cries of delight as people mentioned favorite items that they wanted to include in the issue. Exclamations of, “so cute!” and “delightful!” rang out in the meeting space.

As our theme relates to donations, I hesitate to call any gift small. I truly feel that there is no such thing, and respect every donor’s choice of how much to give. In all honesty, no gift is too small. When I meet someone on a tour and they send in their first gift, I am thrilled no matter how much they give. I feel very much like Ann M. Brackett when she wrote in a January 1886 diary entry about gifts that were delivered to her from distant friends via her brother: “a shawl that sister Ellen left, silver ware from Abbie Babcock, from Mrs. Jervis a portrait of her late husband & ‘Snow bound,’ a volume that was her sister Kate’s—these tokens are very precious to me.”

How often have you given someone a present, and when they gushed over it, you’ve said, “Oh, it’s nothing”? In modesty we trivialize these important gestures, perhaps even replacing “you’re welcome” with “forget it.” George Starbird (1843–1907) didn’t see a small gift of tea as trivial while serving with the 1st New York Mounted Rifles during the Civil War. In his letter home dated February 19, 1863, he recounted torrential rain that left the military camp a sea of mud and a “little brook began to course its path directly under the place I had made my bunk.” Despite the weather conditions and lack of sleep, he wrote, “Tell Mrs. Banks that when I make [a] dipper of tea it makes me think how she would laugh to see me stooping over hot fire, burning fingers in doing it. Tell her she is ever so kind to send it to me and that I do appreciate it and I’ll go now and make me [a] cup.”

Taking the time to give a gift connects the giver and receiver, and this is why we call our supporters the Clements Library Associates. Through your thoughtfulness, you not only help the Clements thrive, but you also forge a closer bond and become part of a community.

Last year gifts of $100 or less totaled almost $35,000. Some donors choose to sign up for monthly giving which adds up quickly; giving over a number of years also makes a huge impact. I am humbled by the number of donors who have been supporting the Clements consistently for 50 years (or more, the current database only shows gifts back to 1975). In particular George F. and Charles L. have been steadfast in their commitment, missing nary a year! This is no small feat. After all, life is busy and letters are pushed to the side and forgotten. We feel the importance of each of these kind gestures, no matter the size, and are grateful for the community that supports the Clements Library.

Moving from her home in Maine to a farm in Lakeville, Minnesota, upon her marriage, Ann Brackett’s diaries demonstrate the importance of the maintaining family ties through correspondence and gifts, large and small. Indeed, the Ann M. Brackett diaries were a gift to the William L. Clements Library from the late Dr. Duane Norman Diedrich.

Staff News

Clements Library Director Paul Erickson completed his term as President of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic at the society’s annual conference in Philadelphia in late July. SHEAR is the primary scholarly organization for scholars working on the history of the U.S. between 1775 and 1861.

Isaac Burgdorf joins the Development team as the new Marketing Coordinator. Isaac is a 2024 graduate from the University of Michigan School of Information and has worked at the Clements as a Manuscripts Assistant since 2022. We are excited that Isaac is now a full-time member of the library staff, and look forward to working with Isaac as he continues to promote the library and its materials through social media and outreach.

The start of a new semester means the opportunity to work with some of the incredibly talented and motivated students from the University of Michigan! This fall, we will be joined by:

- Theresa Azemar – School of Information

- Diana Baxter – School of Information

- Milo Boatwright – LS&A

- Ellie Franklin – School of Information

- Samantha Huck – LS&A

- Anastasiya Ilkiv – LS&A

- Bela Kellog – LS&A

- Madison Lay – Ross School of Business

- Naomi Yu – School of Information

In Memoriam

Richard C. “Dick” Marsh

Dr. Richard Crawford

Dr. Richard Crawford, scholar of American music, died at his home in Ann Arbor on July 23rd, 2024. Dr. Crawford’s connection with the Clements Library started early in his career. His initial dissertation research focused on the papers of Andrew Law, an 18th-century American musician who taught singing and compiled hymnals in Connecticut. The Clements’ holdings of tune books by William Billings were also a fruitful source for Crawford, leading to the publication of William Billings of Boston: Eighteenth-Century Composer, (Princeton, 1975) co-authored with David McKay. A generous teacher and scholar, Richard Crawford led the way in moving the study of American music from the margins of scholarship onto center stage.

Born in 1935, Richard Crawford earned multiple degrees from the University of Michigan (BA in music education, 1958; MA in musicology, 1959; PhD in Musicology, 1965) and served on the faculty until his retirement in 2003. Dr. Crawford donated his papers to the Bentley Library at the University of Michigan.

2024-2025 William L. Clements Library Fellows

Long-Term Fellowships

Jacob M. Price Dissertation Fellowship (2 months)

Ryan Langton, PhD Candidate in History, Temple University; “Negotiating the Endless Mountains: Networked Diplomacy along the Eighteenth-Century Trans-Appalachian Frontier”

Dorothy and Herman Miller Fellowship in Great Lakes History (2 months)

Ramya Swayamprakash, Assistant Professor, School of Interdisciplinary Studies, Grand Valley State University; “Islands in the Straits: Technology, Transformation, and Remarking Nature along the Detroit River 1860-1960”

Ben Pokross, Duane H. King Postdoctoral Fellow, Helmerich Center for American Research at Gilcrease Museum, University of Tulsa; “Writing History in the Nineteenth-Century Great Lakes”

Short-Term Fellowships (1 month)

Norton Strange Townshend Short-Term Fellowship

Ashley Reed, Associate Professor of English, Virginia Tech; “Spiritualist Religion in American Women’s Writing, 1848-1910”

Ben Bascom, Assistant Professor of English, Ball State University; “Eccentric Queers: Sexuality and Debility in Nineteenth-Century America”

Javier Eduardo Ramírez López, PhD Candidate in History, El Colegio de México; “The Great American Bookseller: The Formation and Dispersion of Henry Stevens’s Mexican Collection”

Johann Neem, Professor of History, Western Washington University; “The Daily Life of American Democracy, 1780s–1850s”

Alfred A. Cave Fellowship

Emily Dixon Magness, PhD Candidate in History, William & Mary; “If you had paid attention, you would know”: The Sacred World of Eighteenth-Century CherokeeAnglo Politics”

Howard H. Peckham Fellowship on Revolutionary America

Ronald Angelo Johnson, Associate Professor of History, Baylor University; “Mutual Entanglements: Transracial Ties Between Haitians and Revolutionary Americans”

John W. Shy Memorial Fellowship

Blake McGready, PhD Candidate in History, Graduate Center, City University of New York; “Making Nature’s Nation: The Revolutionary War and Environmental Interdependence in New York, 1775–1783”

John M. Price Short-Term Fellowship

Blake Grindon, Patrick Henry Scholar, Postdoctoral Fellow in History, Johns Hopkins University; “The Death of Jane McCrea: Sovereignty and Violence in the Northeastern Borderlands of the American Revolution”

Julius S. Scott III Fellowship in Caribbean and Atlantic History

Rachel Tils, PhD Candidate in History, University of Chicago; “Marketing in the System: Policing the Antillean Internal Economy. 1763–1807”

Phoebe Labat, PhD Candidate in History, Brown University; “Natural Disasters in the French Atlantic, 1624–1843”

Richard and Mary Jo Marsh Short-Term Fellowship

David R. Whitesell, Independent Scholar; “A Bibliographical Catalog of Pre-1901 American and Canadian Photographically Illustrated Books

MacManus & Co. Fellowship

Henry Knight Lozano, Senior Lecturer in American History, University of Exeter; “Reptile Dominion: A Human-Reptile History of Florida in the Nineteenth Century”

Ephemera Society of America Fellowship

Alexandra Cade, PhD Candidate in History, University of Delaware; “Schottische at the Spa; Waltz at the Waterfall: Sensory Performance of National Identity in Nineteenth-Century American Tourism”

Brian Leigh Dunnigan Fellowship in the History of Cartography

Carli LaPierre, PhD Candidate in History, Queen’s University; “From Where We Stand: Visual Imagery and Understandings of Space in EighteenthCentury Northeastern North America”

Week-Long Fellowships (1 week)

Richard & Mary Jo Marsh Fellowship

Ryan Morini, Director of Community Oral History Collections, Doy Leale McCall Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of South Alabama; “The Unsettled Life of an Eastern Nevada Ghost Town”

David B. Kennedy and Earhart Fellowship

Matthew Skic, Curator of Exhibitions, Museum of the American Revolution; “Loyalists at War: The Story of the Queen’s Rangers”

Brian Leigh Dunnigan Fellowship in the History of Cartography

Alanna Loucks, PhD Candidate in History, Queen’s University; “Imagined Imperial Spaces: Comparing Cartographic Representations of the Great Lakes Region in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century”

Mary G. Stange Fellowship for Creative and Performing Artists and Writers

Tina Villadolid, Independent Scholar; “More Pieces of the Archipelago: Connectivity between UM and the Philippines”

Ruth Lopez, Independent Scholar; “Finding Miss Jennie Curtis”

Alexander Ames, Director of Outreach & Engagement, The Rosenbach Museum & Library / Free Library of Philadelphia Foundation; “’The Sound of Harps Angelical’: A Celtic Harpist Residency at the William L. Clements Library”

Jacob M. Price Week-Long Fellowship

Emily Lampert, PhD Candidate in History, Rice University; “The Virginian Atlantic: Virginia in the British Imagination, 1780–1860”

Jack Werner, PhD Candidate in History, University of Maryland, College Park; “Ableist Empire: U.S Colonialism, Disability, and Labor in the United States and the Philippines, 1898–1916”

James E. Laramy Fellowship in American Visual Culture

Mary Kate Robbett, PhD Candidate in History, Northwestern University; “Collecting the War: Civil War Relics, 1865-1915”

Jeremy McLaughlin, PhD Candidate in Information, University of Wisconsin – Madison; “A Most Familiar Form(e): Textual and Visual Knowledge Transmission in the Cultural Astronomy of Colonial North America”

Norton Strange Townshend Week-Long Fellowship

Jess Libow, Visiting Assistant Professor in the Writing Program, Haverford College; “Obscure Conditions: Visualizing Health in Nineteenth-Century American Literature”

Jordan T. Watkins, Assistant Professor of Church History and Doctrine, Brigham Young University; “Slavery and Religion in the Nineteenth-Century”

Ashley Rattner, Assistant Professor of English, Jacksonville State University; “The Crass Materiality of Utopia: Publishing Communitarian Reform in Nineteenth-Century America”

Clayton Lewis Fellowship in American Culture

Emily Schollenberger, PhD Candidate in Art History, Temple University; “Shifting Sediments: Photography, Memory, and Imperial Landscape”

Introduction to Archival Research Fellowship (1 week)

Forty-Three Foundation Fellowship

Leah Driehorst, Undergraduate, University of Michigan; “Paradox of Progress: Uncovering the Problematic Views of Late 19th-Century American Reformers”

Digital Fellowship (1 week)

Jacob M. Price Digital Fellowship

Surekha Davies, Independent Researcher; “Humans: A Monstrous History”

American Trust for the British Library and William L. Clements Library Fellowship (2 weeks)

Dannie Brice, PhD Candidate in History, Duke University; “Imperial Grounds: Coffee, Entangled Empires, and the British Military Occupation of Saint-Domingue, 1789–1833”

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Santa J. Ono, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, Derek J. Finley, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Kristin A. Cabral, C. Wesley Cowan, Charles R. Eisendrath, Derek J. Finley, Margaret N. Harrington, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Troy E. Hollar, Martha S. Jones, Christina A. Karas, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, James E. Laramy, Ole Lyngklip, Drew Peslar, Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Estrella Salgado, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Peter Heydon, Chair Emeritus

Joanna Schoff, Harold T. Shapiro

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Savitski Design, Ann Arbor

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Sarah Hubbard, Okemos; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Santa J. Ono, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.