No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

Developments

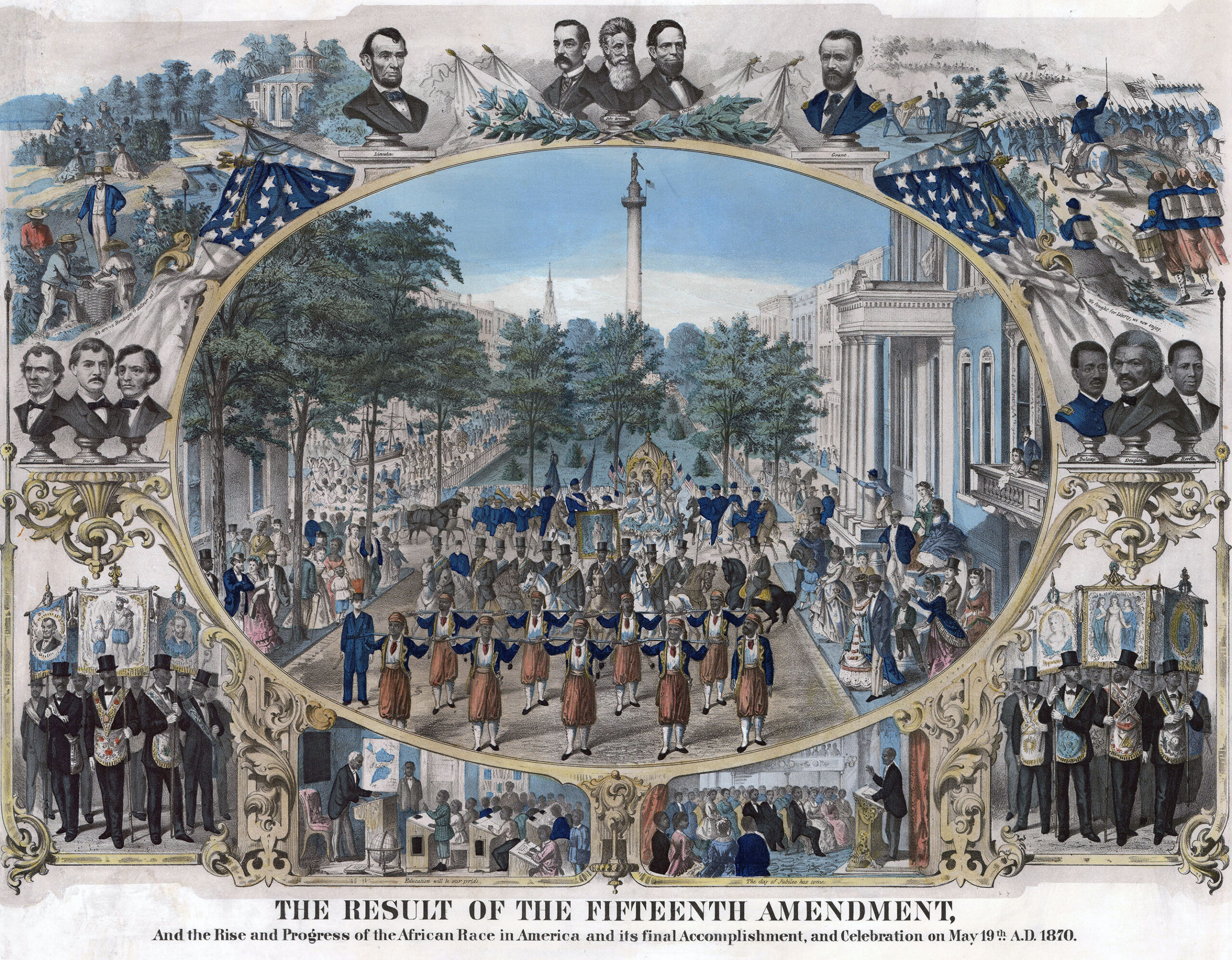

As I’ve seen the stories brought forth by my colleagues for this installment of The Quarto as well as the materials being organized for display in our upcoming exhibit, I’ve been struck by the intersection between arts, resistance, and archives. It’s not that I didn’t know the stories were there among our collections—I just can’t help reflecting on the omissions in the narrative of American history that I learned in school. These are creative expressions that have challenged societal norms, advocated for justice, and amplified the voices of marginalized communities. Graphics materials in the archives have a unique ability to represent the complexities of the human experiences and foster empathy, but also create challenges in processing, housing, and conservation as our fastest growing collections area. Bringing these stories to life often requires financial support, making fundraising a crucial aspect of promoting projects that delve into the archives in new ways.

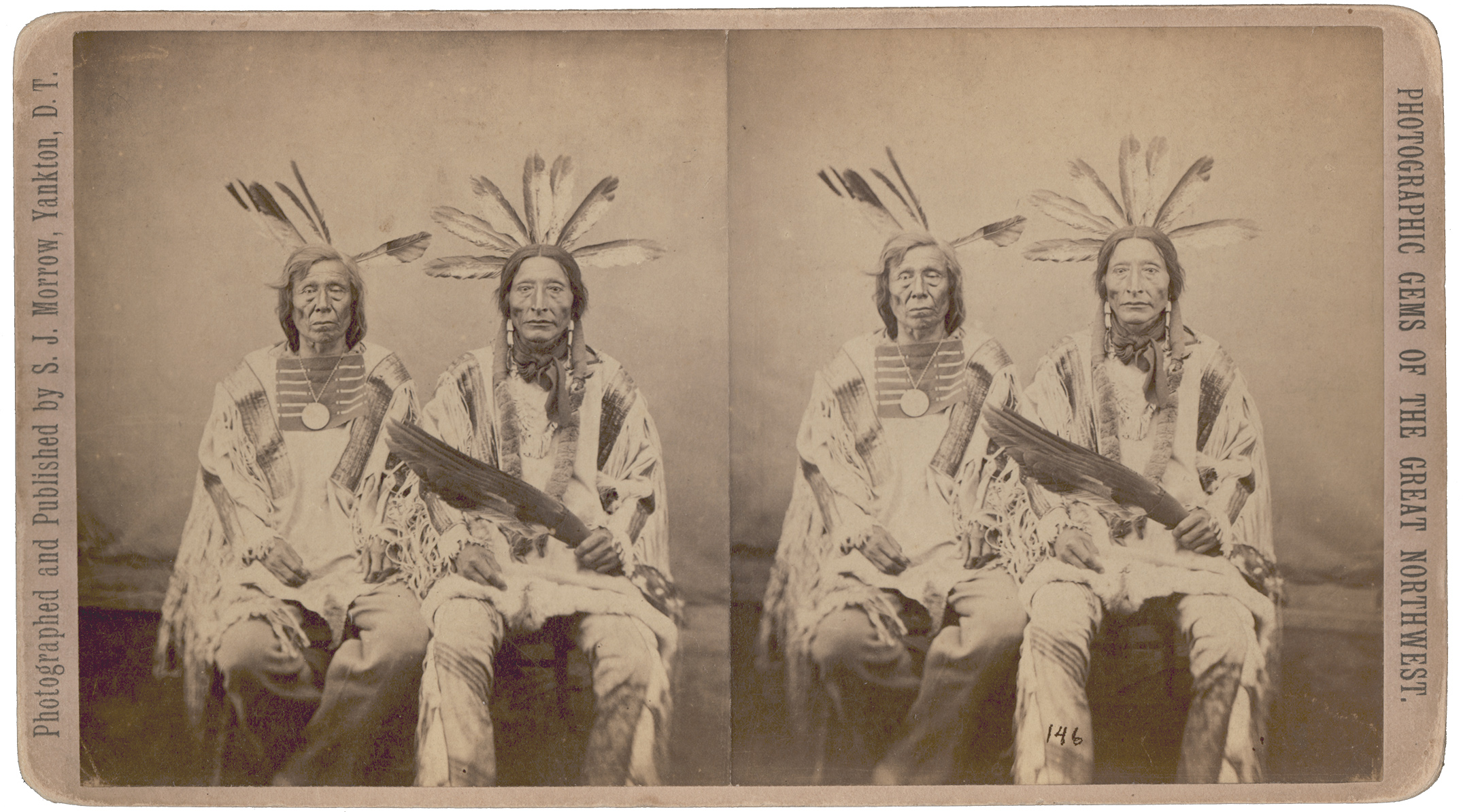

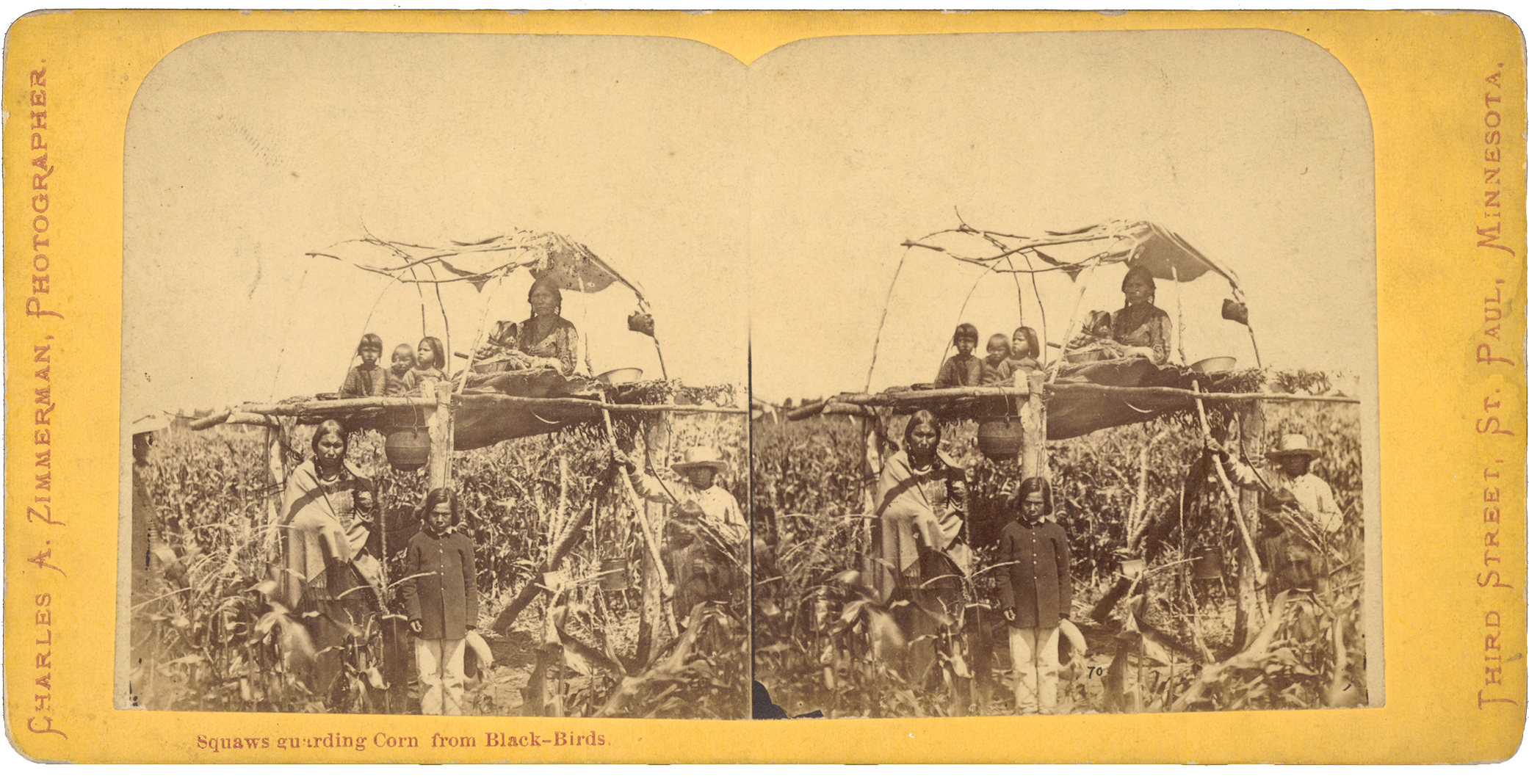

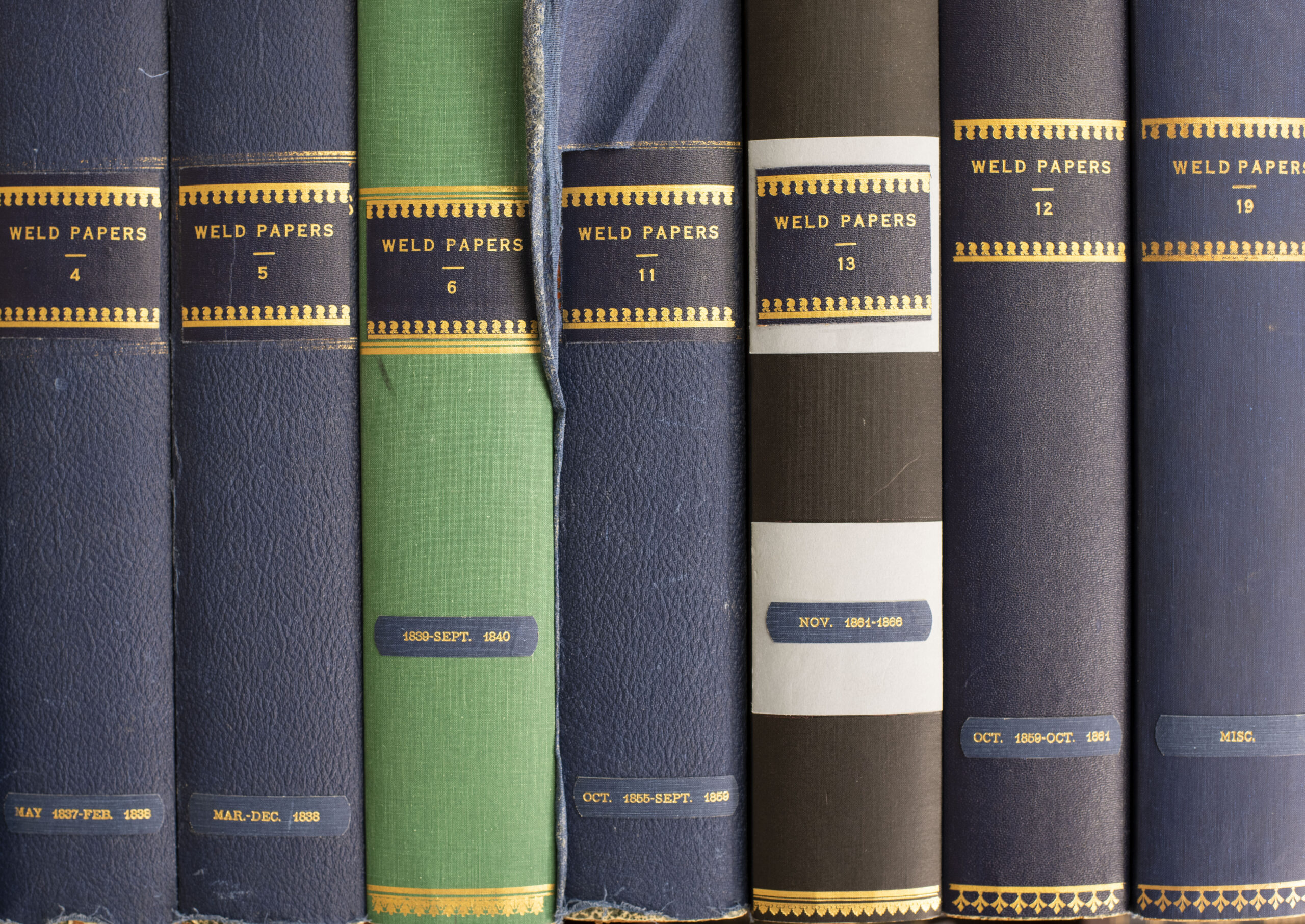

By definition, marginalized voices exist at the periphery of mainstream narratives. Taking the time to identify and illuminate hidden details is often the job of collection processors and catalogers and it can be easy to take for granted the time and skill required to ensure that the materials are well represented and discoverable. The Clements Library has demonstrated the impact funding can have on elevating the accessibility and usability of records. Through grants from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and the Frederick S. Upton Foundation, we were able to take the extra research time required on the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography to ensure that the correct people are identified in the photos, and to include the various English and Indigenous language versions of their names. And this fall we welcome a 2-year graphics cataloging fellow, Annika Dekker, through new funding provided once again by the Delmas and Upton Foundations to assist in organizing and describing other materials in the Graphics Division. Archivists must carefully curate and provide descriptive metadata to ensure that future generations can comprehend the significance of these artistic pieces accurately.

While you have seen in this issue of the Quarto that there are ample examples of Arts and Resistance throughout the collection, I have been thinking a lot about the Graphics Material Division lately. We bid farewell to Clayton Lewis as he retired as curator in June. Through a crowdfunding campaign, friends and colleagues are raising money in his honor to set up the Clayton Lewis American Visual Culture Fellowship. Supporting the travel of visiting researchers, helps to offset the funding cuts in humanities departments around the country and encourages creative research with the Clements collections.

Events

Centennial Gala

To celebrate 100 years of the Clements we hosted a 1920’s themed gala on May 3 which featured: Charleston dance lessons, a historical cocktail class, and silhouette portraits. We celebrated the past, present, and future of the Clements Library with many familiar faces – and some new ones. We look forward to the next 100 years at the Clements. Thank you to all who attended.

Ice Cream Social

100 years old never looked so good! On June 15, the Clements Library gathered staff, friends, family, students, and the greater community of Ann Arbor on the south lawn of the Clements to celebrate its birthday. The community enjoyed complimentary ice cream and activities such as making their own spy quills containing secret messages, coloring pieces from the Clements collection, and checking out a 1923 Duesenberg. Though it seems the best activity of the evening was the unplanned gathering under the 100 year old portico to avoid the rain shower. There’s nothing quite like the detail from an Albert Kahn building. It was a great birthday party and we can’t wait for more in the future!

Staff News

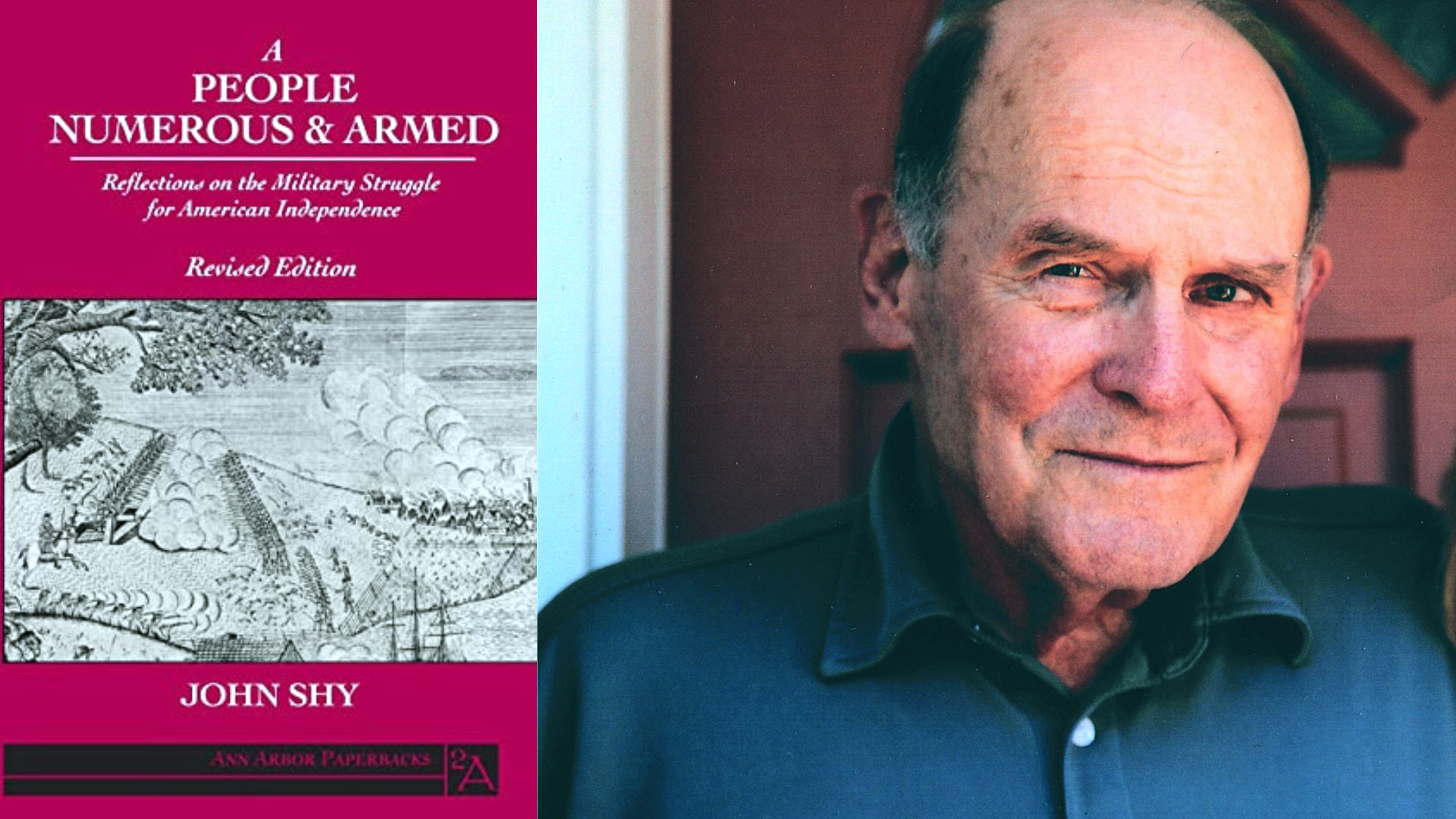

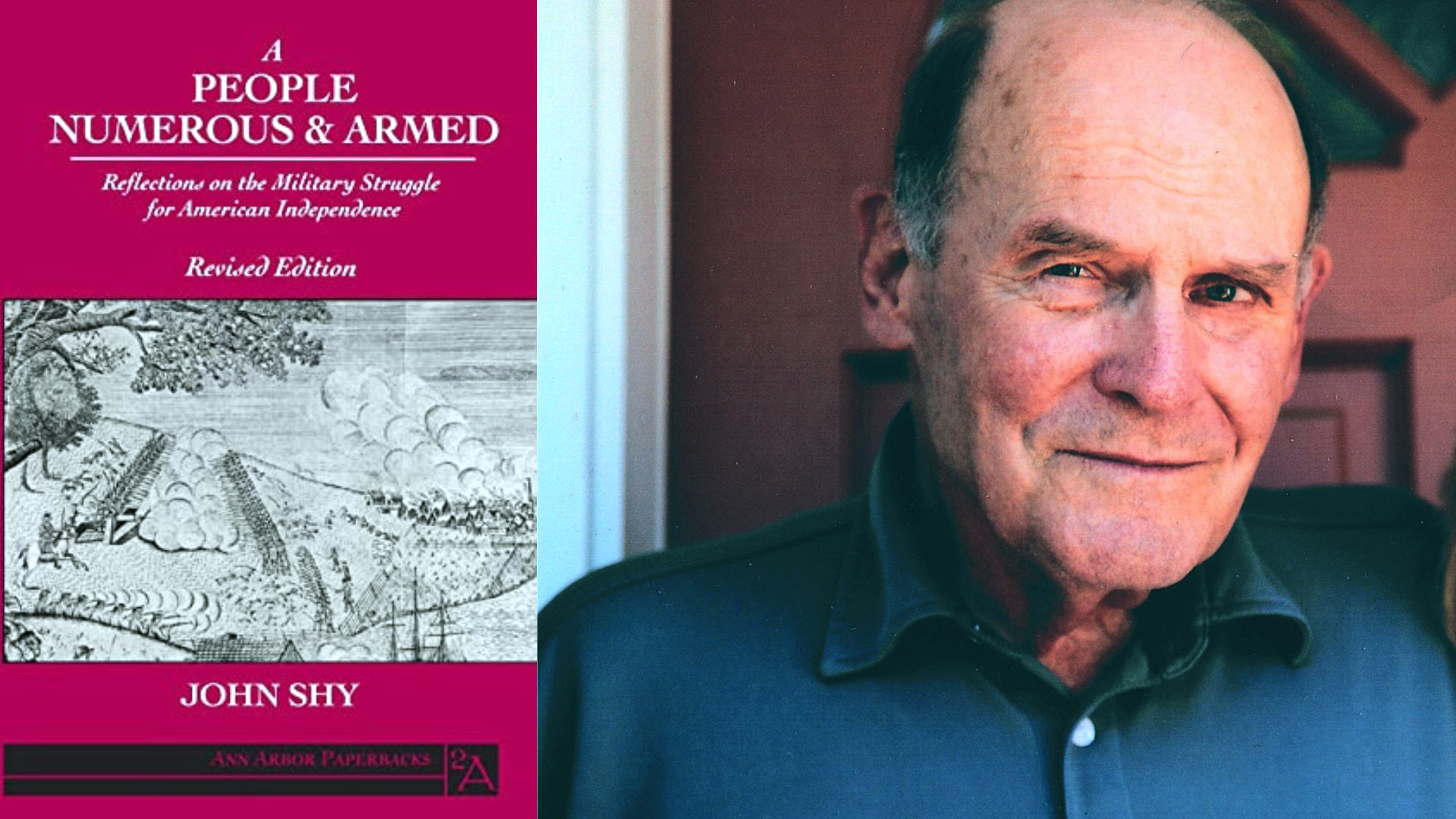

Celebrating the Retirement of Clayton Lewis

We bid farewell and happy retirement to long-time Curator of Graphics Material, Clayton Lewis, on June 20 at the Ann Arbor City Club. In addition to a reception, the program featured speakers sharing stories as well as presentations of gifts in Clayton’s honor. Clayton worked as adjunct faculty to the University of Michigan School of Art and in the field of commercial printing before becoming the first Curator of Graphics Material at the Clements in 2002. He greatly expanded the holdings of the Clements, and worked with donors to secure major collections including the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography and the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography. We wish him all the best on his travels, with scenery to enjoy and an easel by his side.

New Staff Members

Cameron Robertson joins the Digitization team as the new Joyce Bonk Assistant. She is a first-year graduate student at the University of Michigan School of Information and has previous work experience as a curatorial assistant at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

Annika Dekker, an intern at the Clements Library working with our Graphics collections, is also a first-year graduate student in the University’s School of Information, where she plans to pursue studies in Digital Archives and Library Science/Preservation. Annika’s internship is supported by grants from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation and the Frederick S. Upton Foundation.

The Reader Services Division welcomes Emma Schneider to assist in the reading room and with curatorial projects. Emma graduated from Kalamazoo College with a degree in religion, and has previous experience working as an outdoor adventure guide, and organizing the archives at Interlochen Arts Academy.

No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

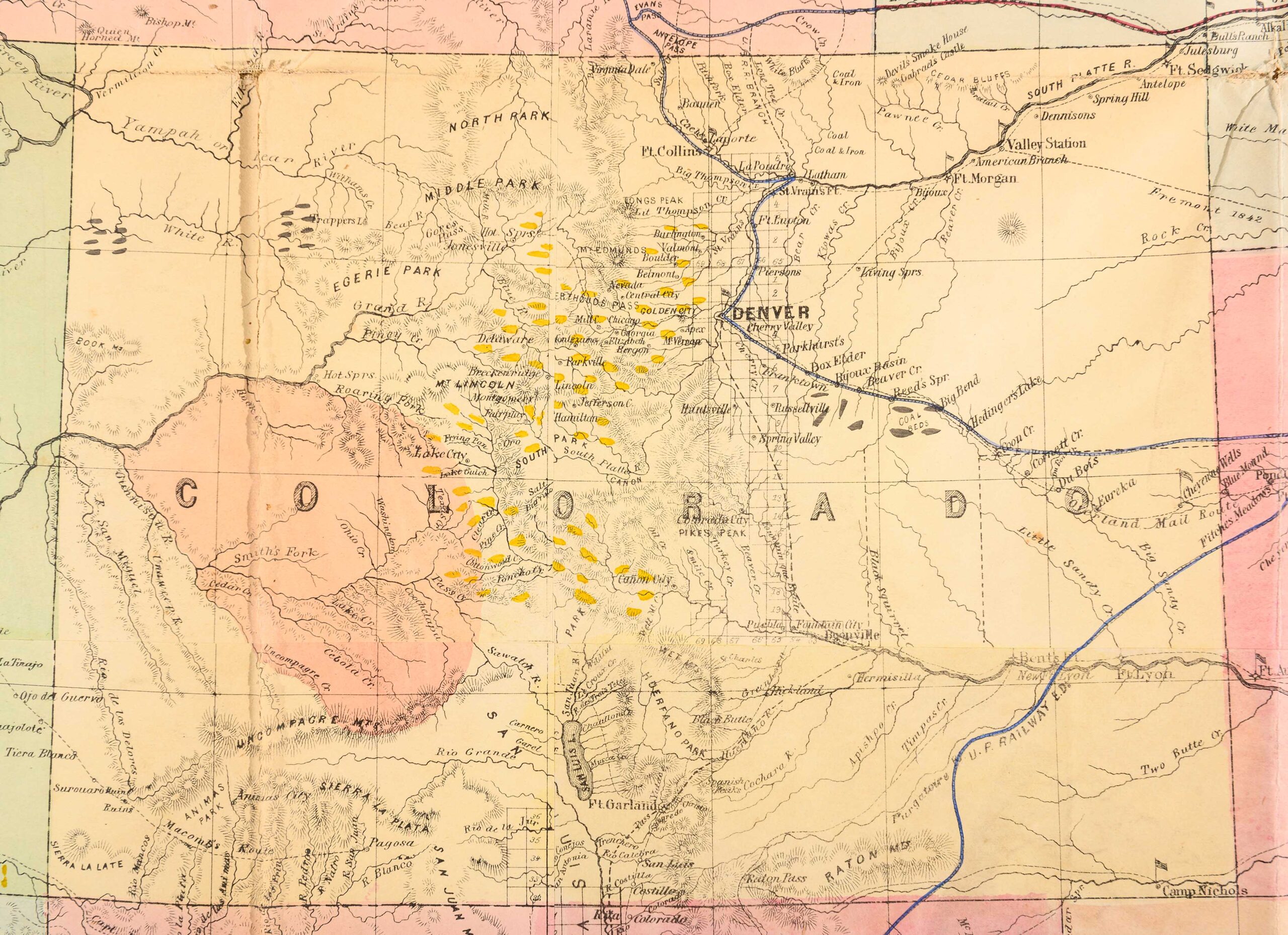

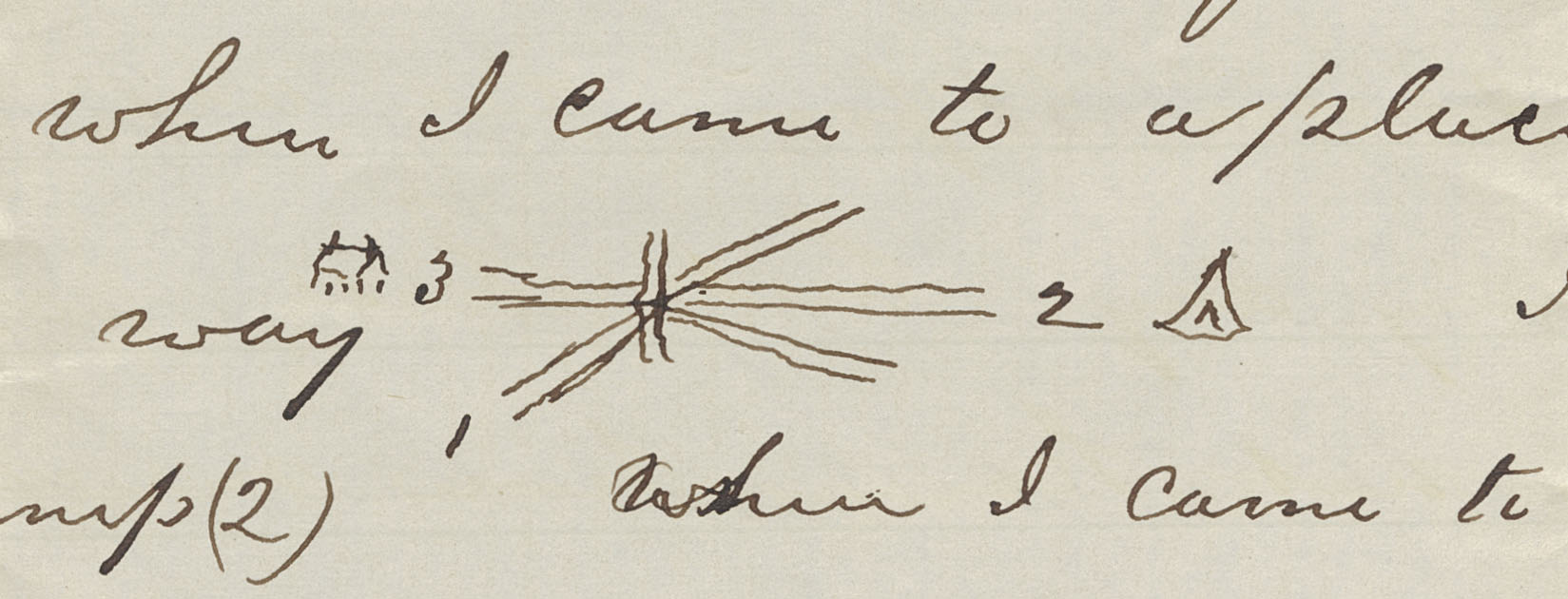

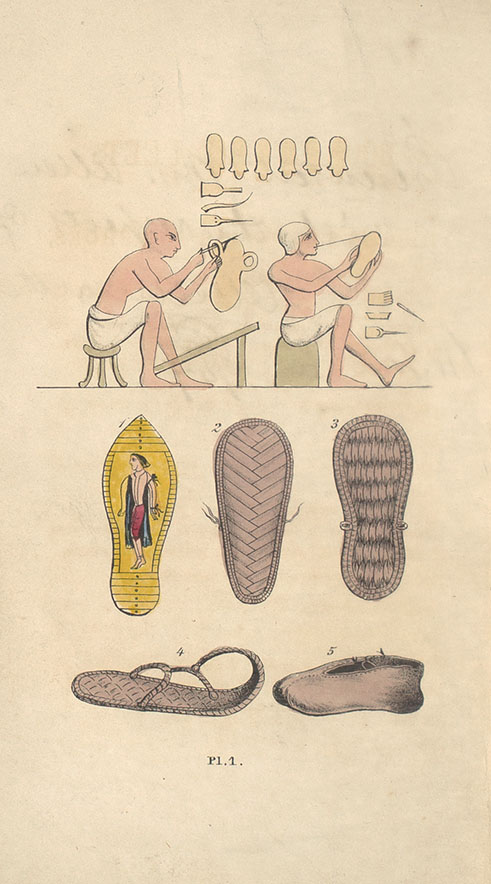

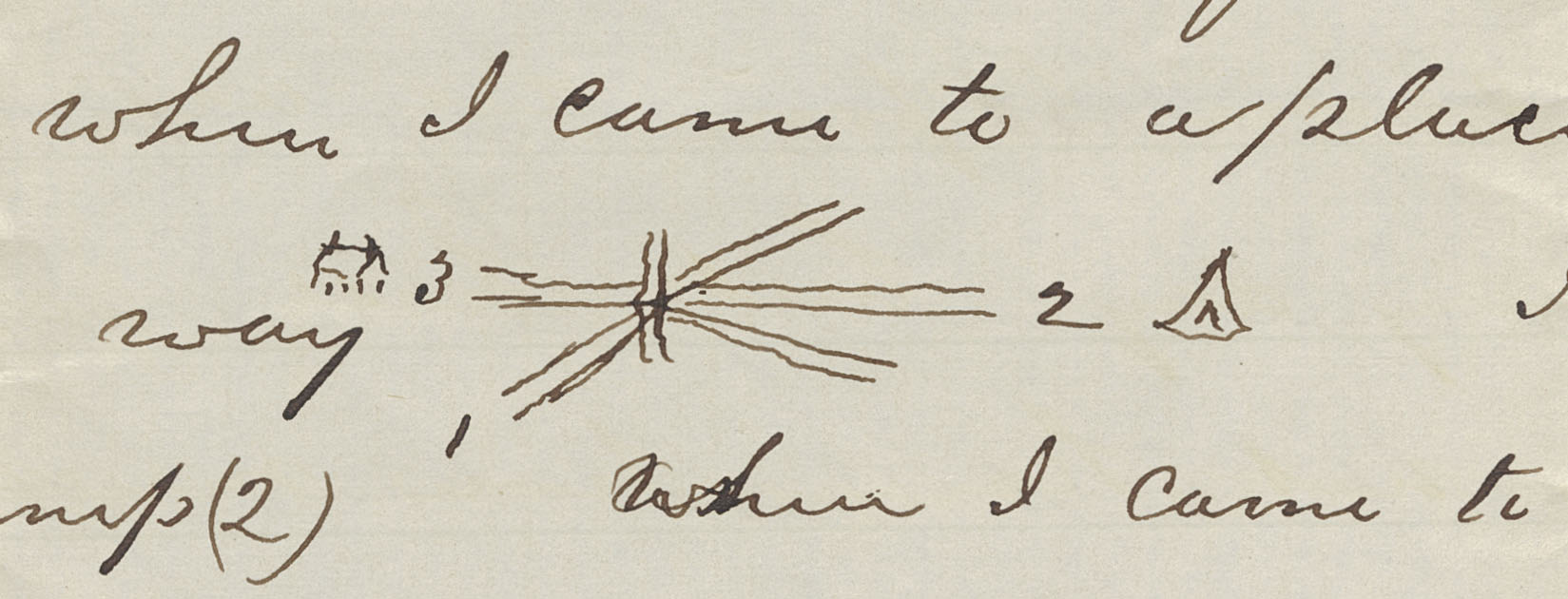

Teaching Geography

The Clements Library holds a number of student maps, drawn or traced by young scholars in the 19th century as part of their school curriculum. The remarkable detail and skill demonstrated by some of these students raise the question of how exactly the maps were made—by tracing? By memory and free-hand drawing? A partial answer may be found in the recently acquired Monteith’s Map-Drawing and Object Lessons, (New York, 1869), a scarce guide to cartography for teachers and school children written by James Monteith, a leading 19th-century American geography educator . Monteith provided exercises on the use of scale, instructions for coloring maps, and the order to be followed when adding features to a map. The symbology and ancillary detail in Monteith’s later map designs led to his nickname, “master of the margins.”

James Monteith used ingenious depictions of animals and everyday objects as an aide-memoire for students working to outline or identify countries and states in their geography lessons.

Hair Album

The Clements Library collection includes a number of hair albums, but the newly purchased Maria Marsh Hair Album 1850–1853 stands out for several reasons. The album contains around 100 hair samples, an unusually large number, and there is work to be done in tracking some of the relationships represented in the album. Other albums tend to contain intricately worked hair samples, but these are quite simple, many with a blunt cut where one can almost feel the snip of the scissors close to one’s ear. Also intriguing are these beautiful metallic hearts that are used to affix the hair to the album pages, adding an extra element of affection and care. The most heartbreaking is the sample taken from the head of an unnamed infant who died at four months of age. The hair was too short to loop, and only one side shows evidence of scissors, since the infant’s feathery hair had not yet grown long enough for a first haircut.

Sager Family Register

Another item drawing us into a personal family history is the Sager Family Register, [ca. 1840?]. The traditional recordings of family births and deaths were enhanced by intricate drawings including some wonderful manicules. The high infant mortality during the 19th century is common knowledge, but looking at the entry for the death of an unnamed infant brings home the impact. The drawings have a folk art quality, and intrigue the researcher with questions. Why does a drawing of a quill pen appear on the page of the unnamed baby? To represent the power of writing or inscribing? The visual qualities are evocative, and the time and care spent on the entries give poignancy and weight to these records of family members entering and leaving the Sager family circle.

Adam Sager’s entry in the Sager Family Register

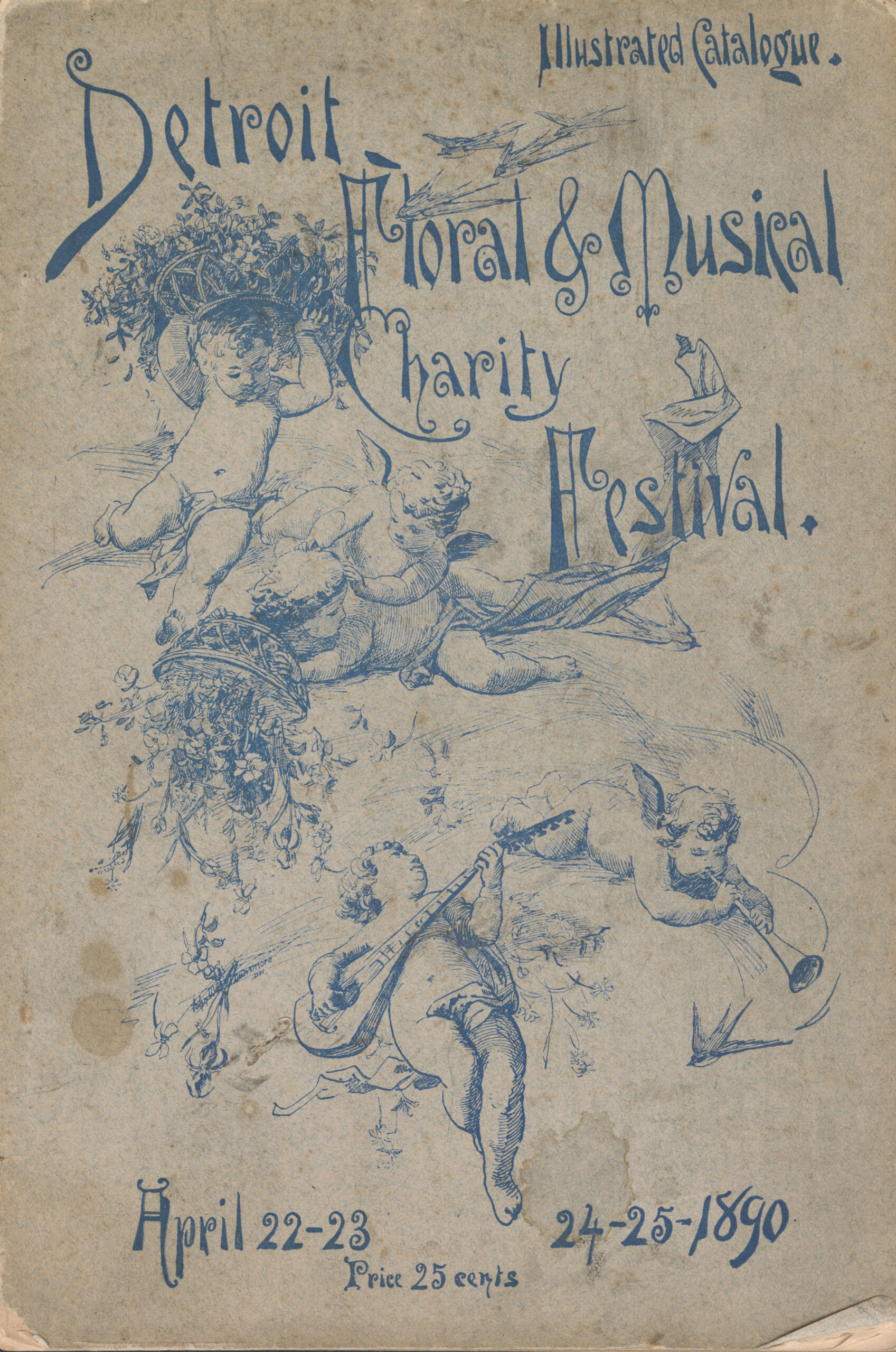

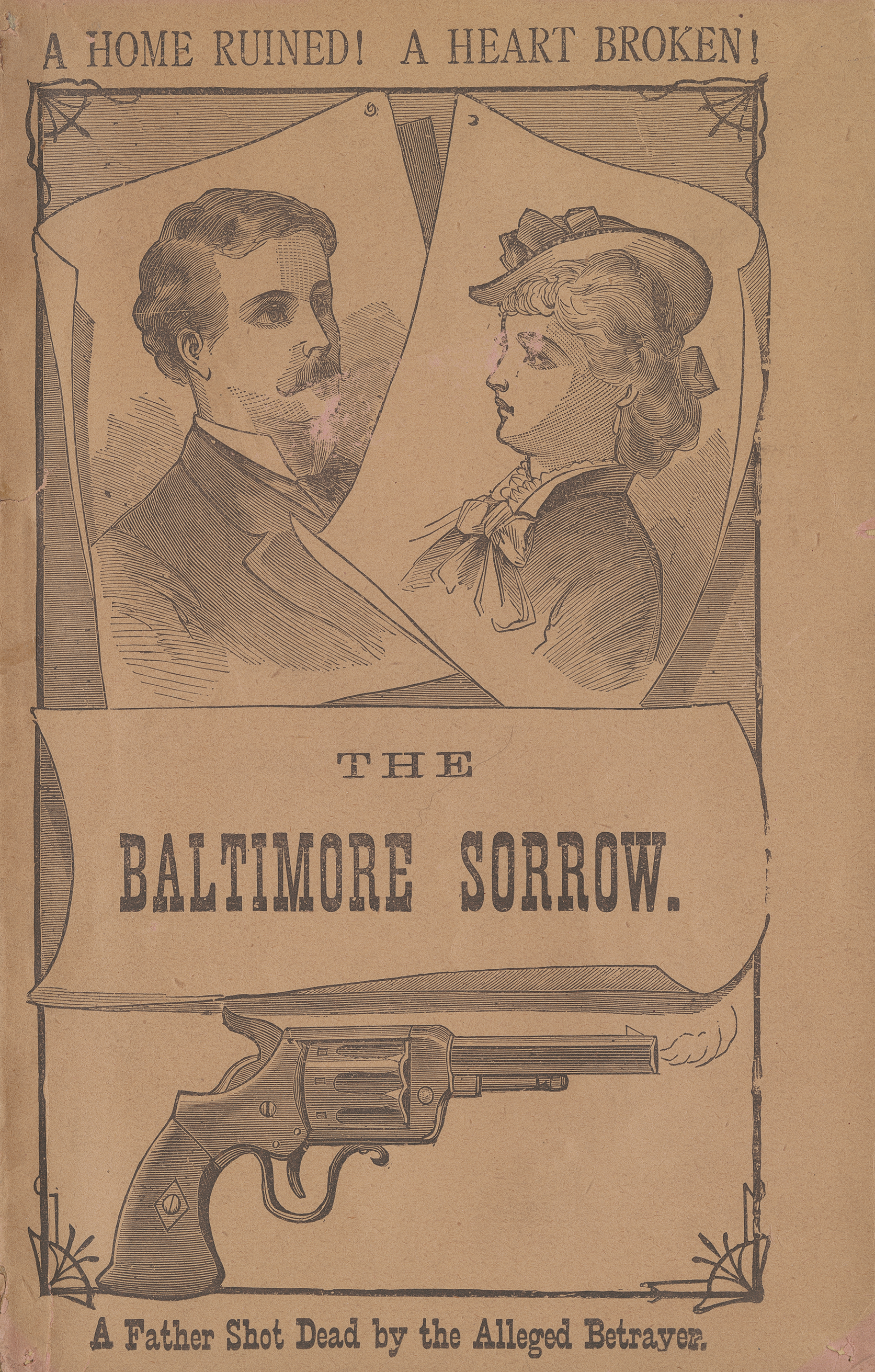

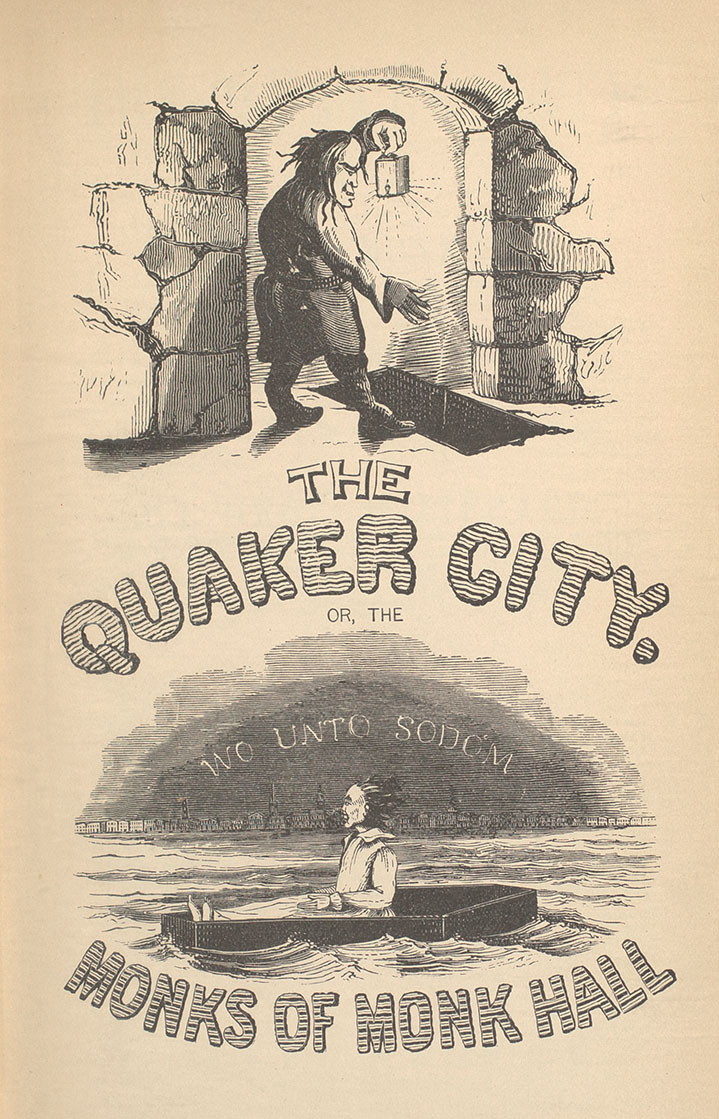

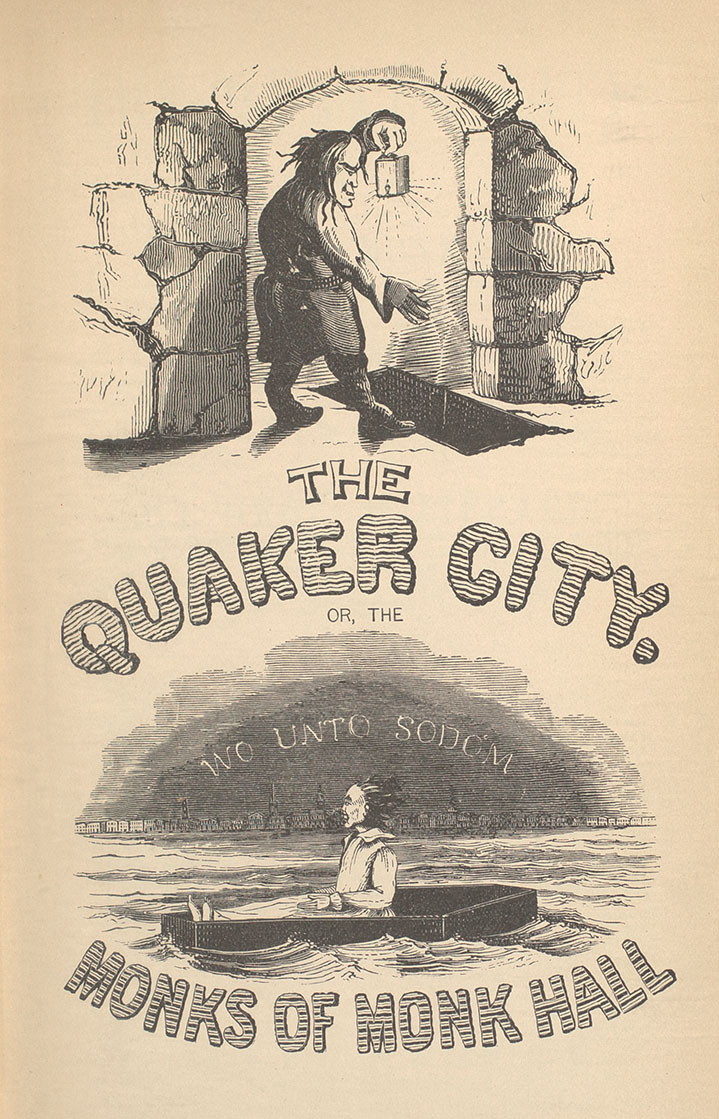

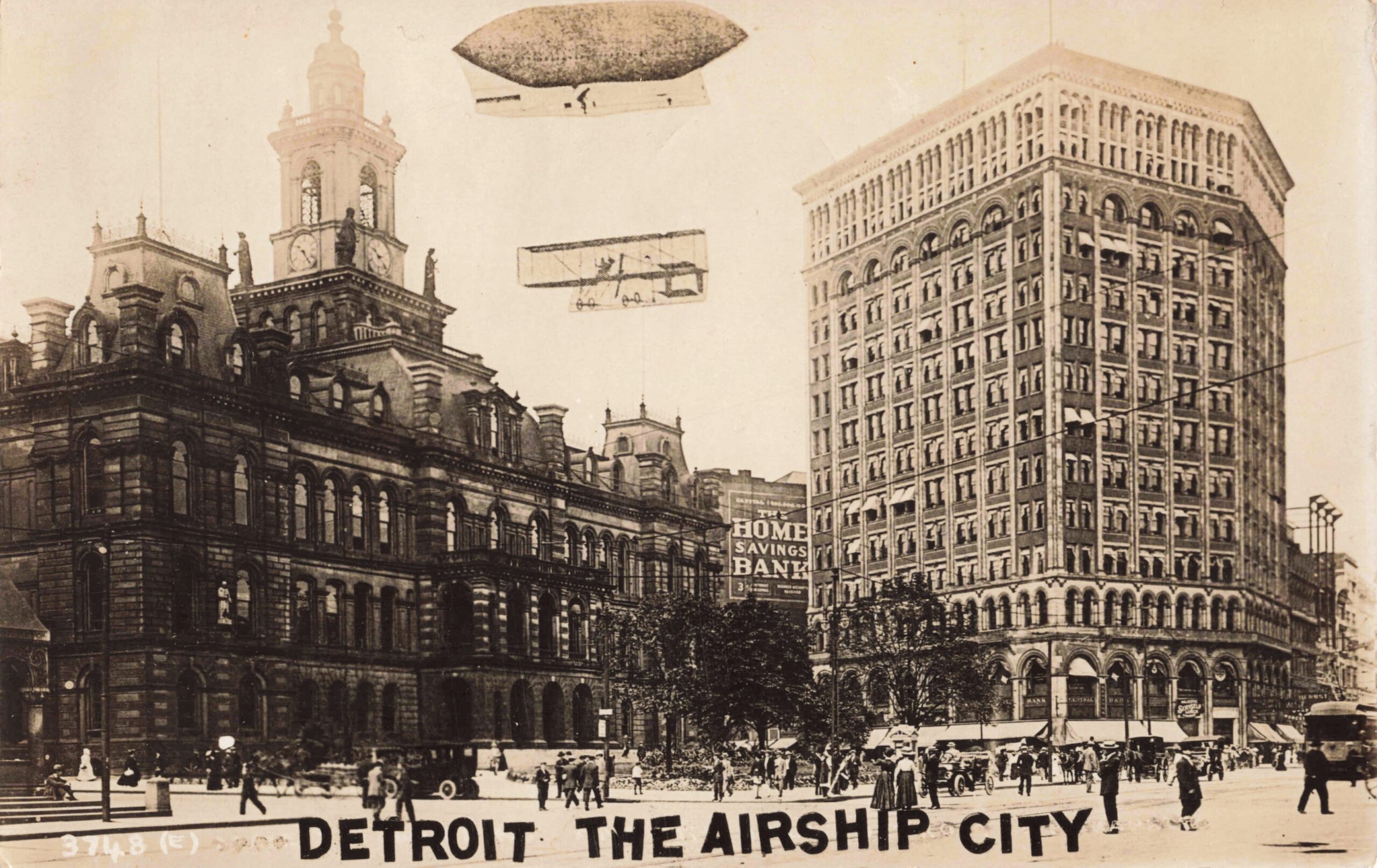

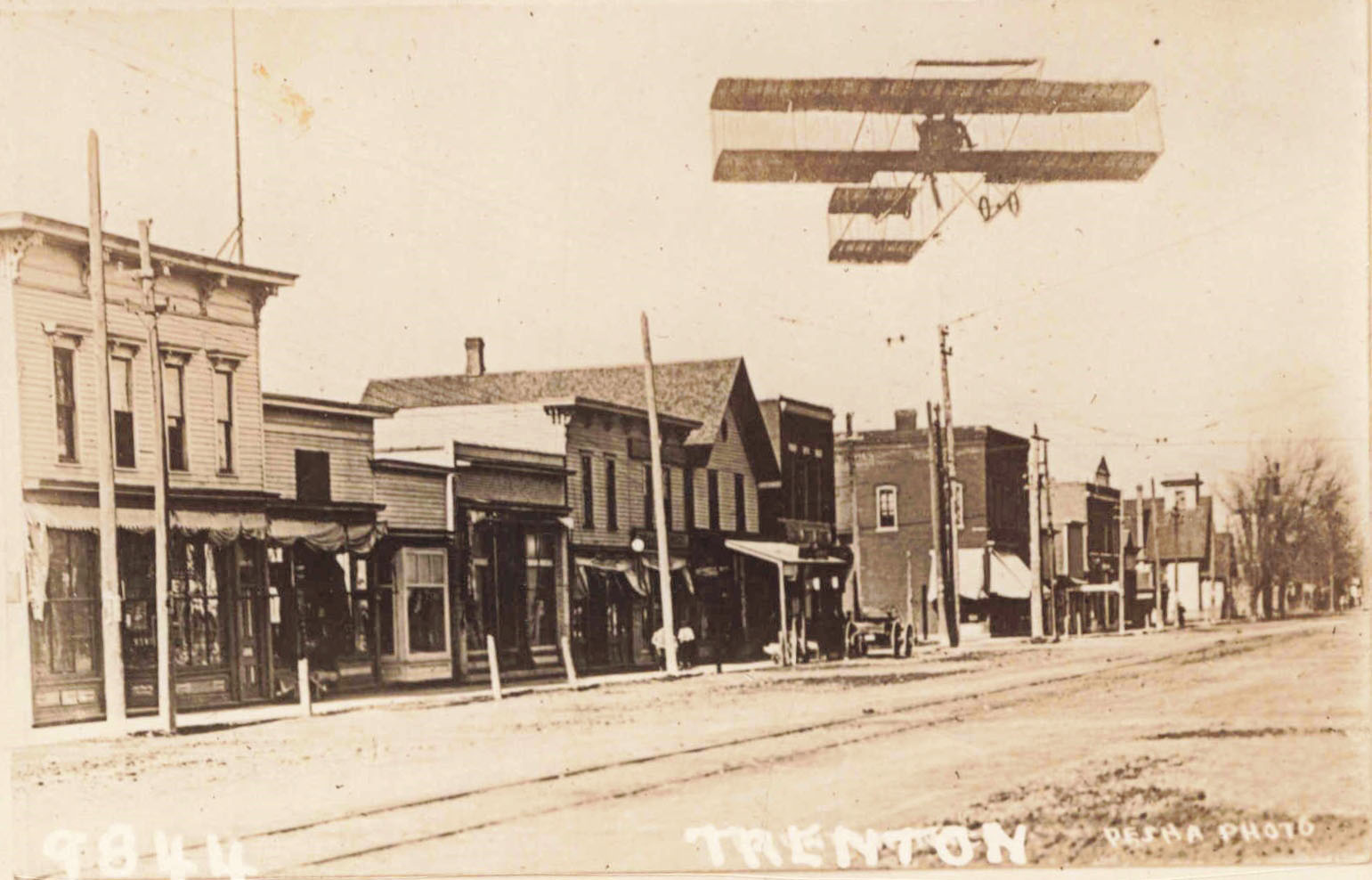

The Frank Reade series

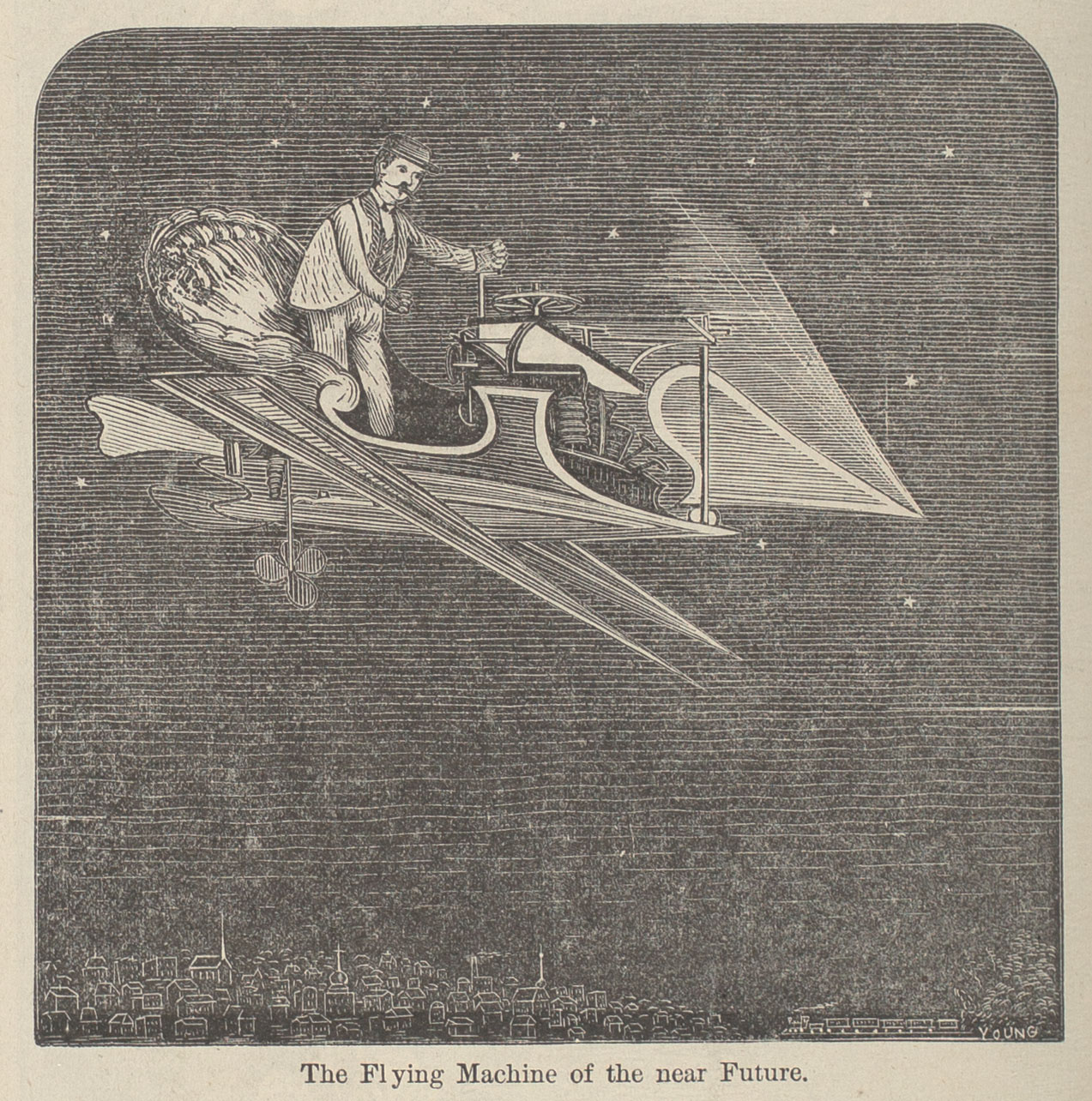

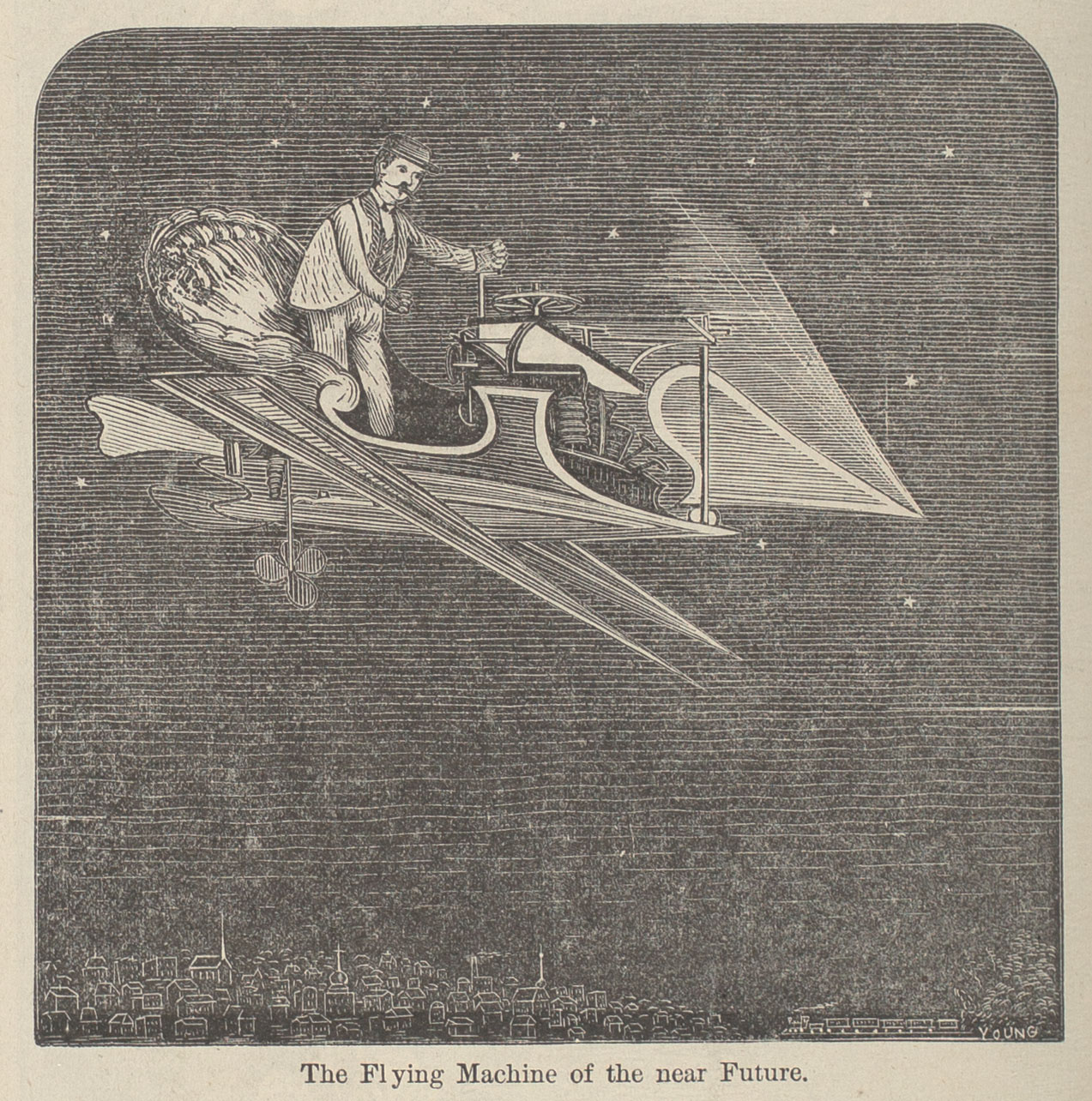

Awaiting cataloging and shelving at the Clements is a single-volume compilation of periodicals from the Wide Wake Library, including 20 issues from the Frank Reade series and 15 issues from Beadle’s Half-Dime Library (featuring Broadway Billy and Deadwood Dick), originally issued between 1883 and 1890. The Frank Reade series was the first science fiction periodical in the world and has been referred to as the lost ancestor of steampunk. Featuring the adventures of several generations of the Reade family, the series channeled the optimism and excitement of the age, sparked by the seemingly unlimited possibilities of electricity, steam power, and other advances. Boy inventor Frank Reade produced robots, submarines, airships, automobiles, and any number of ingenious devices which played key roles in the stories. The series captures a moment in time before corporations took over the business of inventing, Thomas Edison was a hero, there was collective optimism about the beneficial uses of technology, the myth of the American West was taking shape, and the spread of these new inventions served to connect distant parts of the country.

Author Harold Enron wrote the first four issues of the Frank Reade series, including, The Steam Man of the Plains. As described by Enron, the steam man “was a structure of iron plates joined in sections with rivets, hinges or bars as the needs required…. The hollow legs and arms of the man made the reservoirs or boilers. In the broad chest was the furnace…. The tall hat worn by the man formed the smoke stack. The driving rods, in sections, extended down the man’s legs, and could be set in motion so skillfully that a tremendous stride was attained, and a speed far beyond belief.”

The Children’s Hour

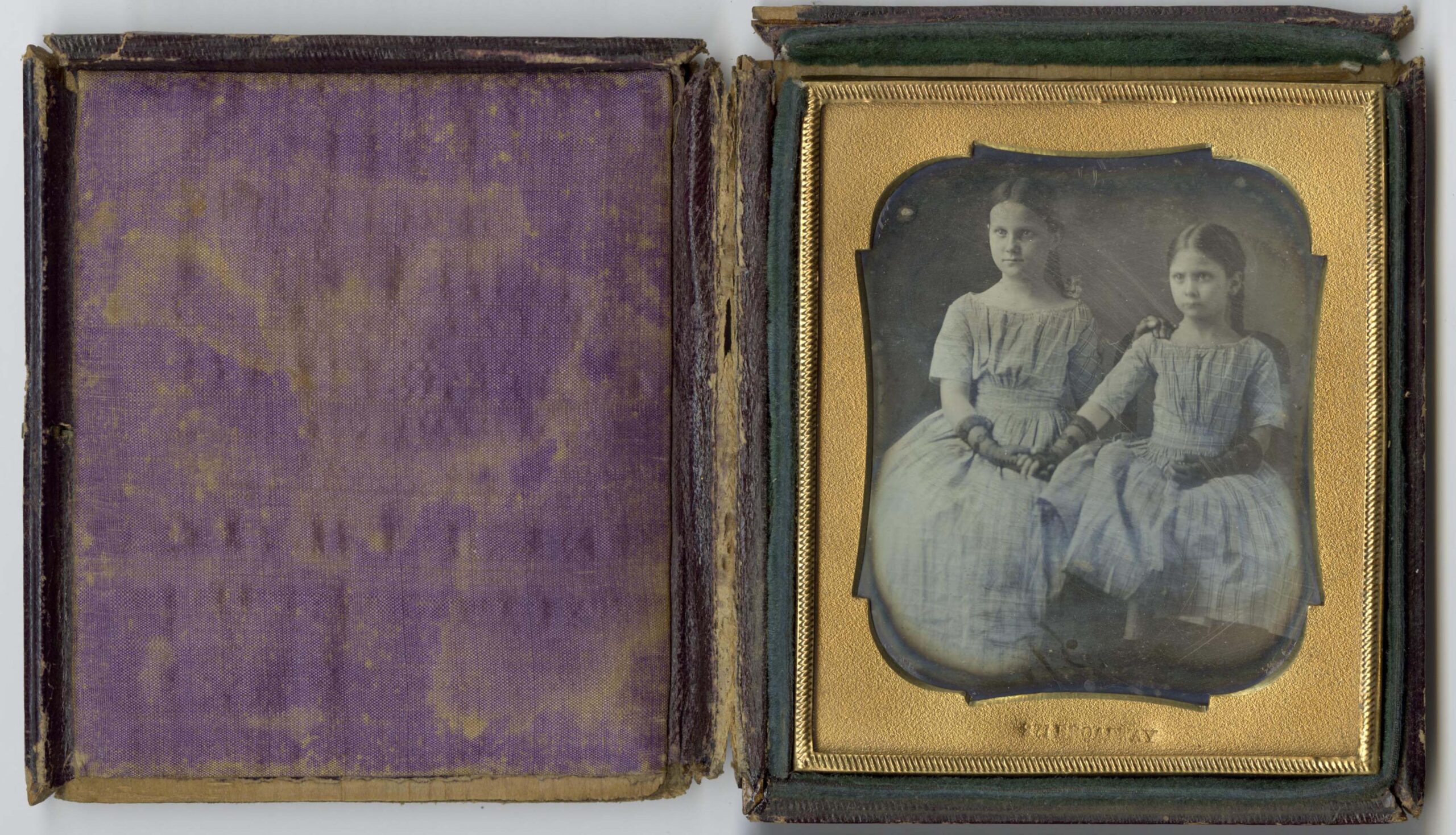

Several photographic items related to children and their experiences, including interactions with 19th-century print culture, have come into the Clements Library recently.

The photograph on this real photo postcard was taken by a child of her dolls set up in front of a dollhouse. Alice Wright, the photographer, used a caption which might present an interesting topic for future study.

This carte de visite photograph depicts a child reading a copy of Puss ‘N Boots. It’s possible that the book was not simply a prop but perhaps how the child was convinced to pose for the photographer.

The Children’s Hour

Three small pamphlets, the largest measuring 6 x 4½ inches, Additions to our children’s literature and tiny book collections include three recent finds. In a tiny pamphlet, Rufus Merrill (1803–1891), one of the biggest provincial publishers (Concord, NH) took a firm stand in the perennially thorny dog vs. cat debate. Book About Dogs and Cats (Concord, N.H.,1856) reports that cats are undesirable, “self-willed and forward to the last degree,” whereas when it comes to dogs, “No other animal is gifted with so much sagacity or is so faithful to his master.” This pamphlet additionally gives us the name of an owner, signed inside the back cover by Theodore Huff on October 1, 1860, so it may be possible to connect this item to an individual and his life circumstances at the time he acquired it.

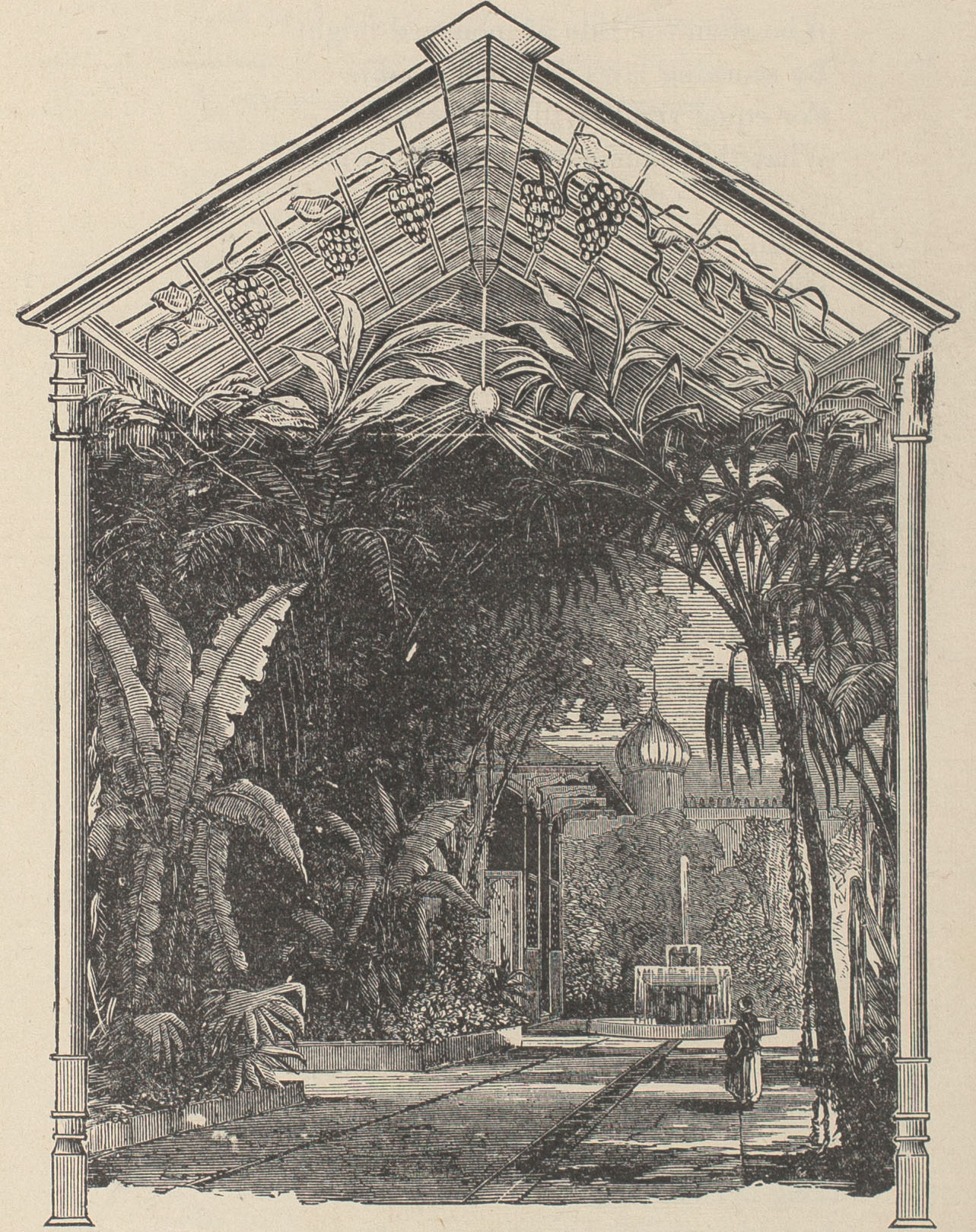

One might expect to find a morality tale when opening the next item, Who Stole the Grapes, published by the Sunday School Union in New York between 1856 and 1858; but one may be surprised by the lesson learned. Rather than a wayward child deterred from a life of crime, the bad actor in the story was a spiteful teacher, who framed the boy for the theft. Falsely accused, the boy recognized the virtue in not seeking revenge against one’s persecutors.

The last item is an illustrated pamphlet titled Jerry, Jenny and Jim, published by the Chicago Corset Company between 1882 and 1889. An example of how things were circulated and re-circulated, the backsheet advertisement for a dry goods store in Fargo was likely added to the item after its arrival in the Dakota Territory. The story concerns Jim Jumbletum, his wife, and his mule. But the footnote text that runs throughout the story contains information on Ball’s H.P. corsets, including the endorsement of the corset’s elastic side section, which “emits no disagreeable odor, and will not heat the person or decay with age.” It’s an odd combination of an amusing illustrated story for kids with an extended, very specific ad for corsets. At the end Jim learns the importance of purchasing the right corset for his wife.

No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

When I first started as an intern at the Clements Library, I was tasked with organizing the papers of Marilla Waite Freeman (1871–1961), part of the Dwight- Willard-Alden-Allen-Freeman Family Papers. The papers relating to Freeman, a public librarian, and her family extend back through multiple generations. Reading Freeman’s correspondence and documents painted a beautiful picture of the woman that she was and drew me deeper emotionally into the field of library science (I am now a graduate student at the University of Michigan School of Information). Freeman worked as a public librarian for roughly fifty years, finally retiring in 1940 from her position directing the Cleveland Public Library. While working in Cleveland she was very involved in the local Novel Club, a group of thirty-five men and women, some of them university faculty members and their wives.

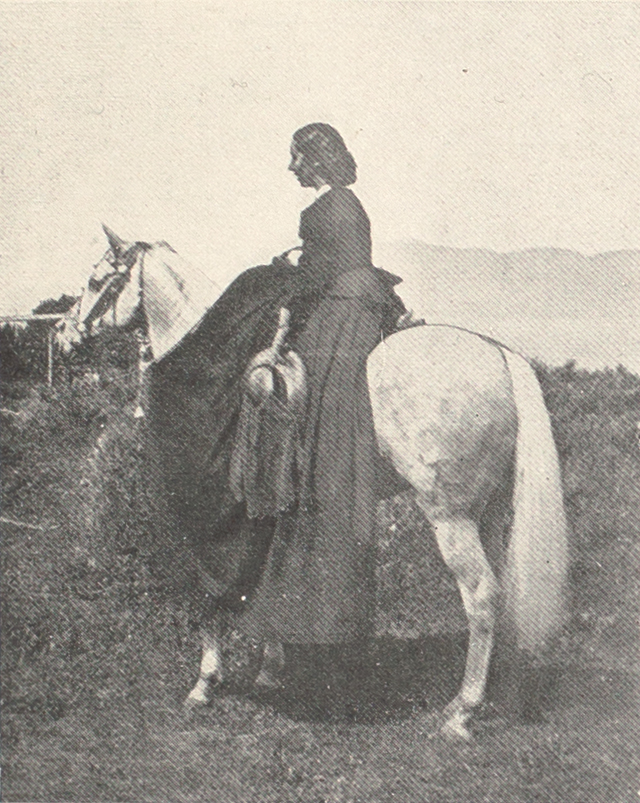

Freeman obtained prominence in her field, referred to as “one of the best known and most beloved librarians in the country” by the Cleveland Plain Dealer upon her retirement in 1940. Photograph courtesy of The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Marilla Waite Freeman.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digital collections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-bef2-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

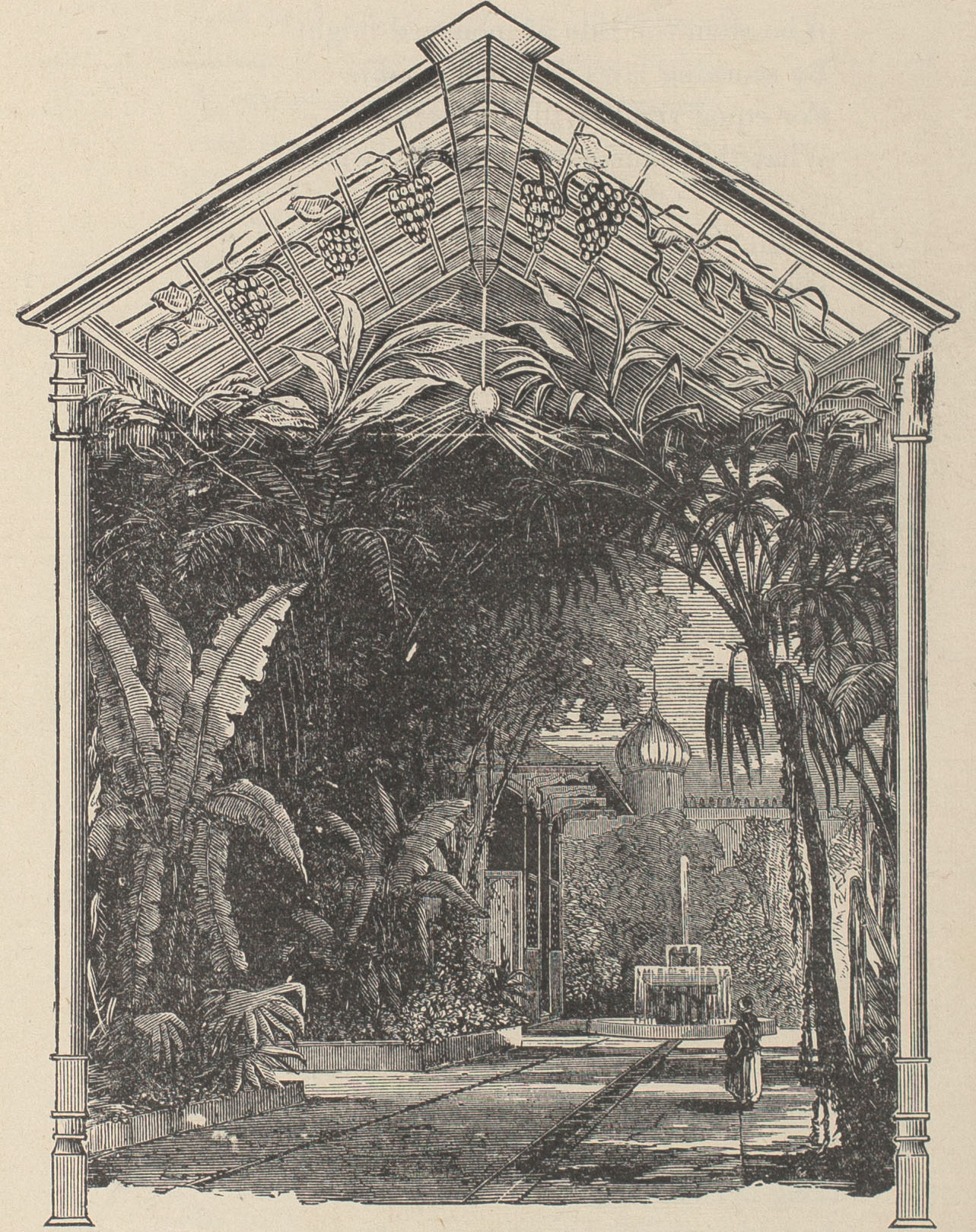

The Novel Club met to discuss James Hilton’s Lost Horizon in December 1935, two years after its initial publication. Four years later the novel would top Simon & Schuster’s list of mass-marketed Pocket Books. Lost Horizon related the story of four people kidnapped while fleeing conflict in the fictional city of Baskul and taken to the Tibetan Kunlun mountains. They were brought to a utopian valley where the inhabitants lived to be hundreds of years old and moderation was the rule of the land. This valley was home to the mythical lamasery called “Shangri-La,” which has since become a catchphrase meant to invoke images of a paradise, typically in a location perceived as distant and exotic.

Freeman compiled a list of discussion questions for the group along with a biographical sketch of Hilton, using information received from his publishers and from Hilton himself. In his correspondence with Freeman, Hilton praised her reading of the tale: “I wish I could explain more fully in a letter the philosophy of the book, but I can see from your own suggestions that you have read it with much sympathy and understanding” (September 3, 1935). As an homage to Marilla Freeman, a few staff members here at the Clements Library chose to host our own book club to read and discuss the novel using her questions as a guide.

James Hilton’s concern about the fate of the arts during times of conflict was prescient. The onset of World War II just 6 years after his novel was published, led to the destruction of literary and artistic works across Europe and Asia. This Japanese print, showing views of Tokyo at the time of Commodore Perry’s second visit in 1854, includes a handwritten note in the margin indicating that this copy survived an air raid in a shelter on the evening of April 13, 1945.

The most striking of Freeman’s questions asked if the “world cataclysm” that Hilton warned about was already upon them. Looking back, Hilton’s words feel prophetic, coming between world wars: Hitler rose to power two years before the club met to discuss Lost Horizon; they were a few years into the Great Depression; and the first major drought contributing to the Dust Bowl had occurred the year before. Unfortunately, most of the Novel Group responses were not recorded, so we can only speculate how the group might have responded to this question. Our book club discussed our perception that a cataclysm has been ongoing for some time now, and that maybe there has never been a time when the feeling of impending doom fully disappears.

In the novel, one of Shangri-La’s central purposes was to act as a repository for a large library of books and art, reflecting Hilton’s very real worries about these treasures being lost in times of conflict. He expressed this fear in an interview, stating that, “If humanity rushes on at its present headlong speed it must inevitably crash sooner or later. When that time comes I’m afraid all the precious things in this world will be lost—books, pictures, music . . . ”. This focus on Shangri-La as an archive piqued the interest of the Novel Club here at the Clements Library, calling to mind a Japanese print in our collection marked with a stamp indicating that it was held in a bomb shelter throughout WWII for its safety.

Freeman wondered if “Eastern mysticism” was one of the main draws of Hilton’s story. The Clements group reflected that Hilton referenced “Eastern” themes and ideas in a manner that may not have been challenging to white audiences of the time. While reading this book and watching the original film adaptation, depictions of Tibetan and Chinese characters stood out as racist caricatures. Although Shangri-La is in Tibet, it’s explained that Tibetan and Chinese people don’t have the stamina to live as long as white people. The leader and founder of the lamasery, the High Lama, is himself a French Christian. On top of this, the film adaptation casts a white man in the main speaking Chinese role, for which he received an Academy Award nomination.

Freeman’s correspondence with James HIlton revealed the author’s hope that his novel would focus attention on his fear that “the world has reached a parting of the ways in which a decision must be made between the reign of violence and that of the quieter life; otherwise, civilization as we know it will perish from the earth.”

While many of these depictions were viewed as offensive by our book club today, we did wonder if the novel’s portrayals came across as progressive in its day. Conway, the main character of the story, settles into Shangri-La quite quickly. This is in part because of the decade that he spent living in China, leading him to feel “at home with Chinese ways,” hinting at the positive effects of a non-Western culture. While Hilton did seem to have a real reverence for Tibet, he never actually visited the region: “I entertain a lot of dreams and illusions about it that would probably be rudely shattered. I prefer to keep them intact,” he explained in an interview. One of my coworkers brought up the point that something similar might happen in our work, where something we write with the intention of being inclusive and respectful might be considered offensive to future readers.

The one recorded response of the original Novel Club was to the question regarding the success of the novel, which the members attributed to “Its peace, its picture of a place of refuge from the present world unrest.” Freeman’s discussion questions for the Novel Club included the prompt, “What would we do if a Novel Club picnic should meet with the experience related in this book?” Like the character Mallinson who spent the entirety of the story looking for a way to escape, perhaps some would resent being kept away from their friends, family, and the life that they had built back home. Others, myself included, viewed Shangri-La as a restful opportunity to take a break from our busy day-today lives.

In the novel, one of Shangri-La’s central purposes was to act as a repository for a large library of books and art, reflecting Hilton’s very real worries about these treasures being lost in times of conflict.

The importance of rest and relaxation is emphasized throughout Lost Horizon. Upon hearing the phrase “slacker” being used in a negative manner, a resident of Shangri-La remarks, “Is there not too much tension in the world at present, and might it not be better if more people were slackers?” The 1973 musical film adaptation of the book includes the very charming song “The Things I Will Not Miss,” which features a long-term inhabitant of Shangri-La expressing her desire to leave the lamasery and a woman who was more recently brought there wishing to stay. The one thing that both characters fully agree on is that they would not miss work, which I feel is a sentiment most of the audience past and present can relate to. The focus on (moderate) relaxation in the story feels revolutionary and freeing to imagine.

Joining the previous members of Cleveland’s Novel Club across time was a very moving and impactful experience. The opportunity to slow down and analyze a piece of literature with my colleagues helped me to better understand my fellow staff members and the novel, and to share a literary experience with like-minded book lovers of almost a century ago.

No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

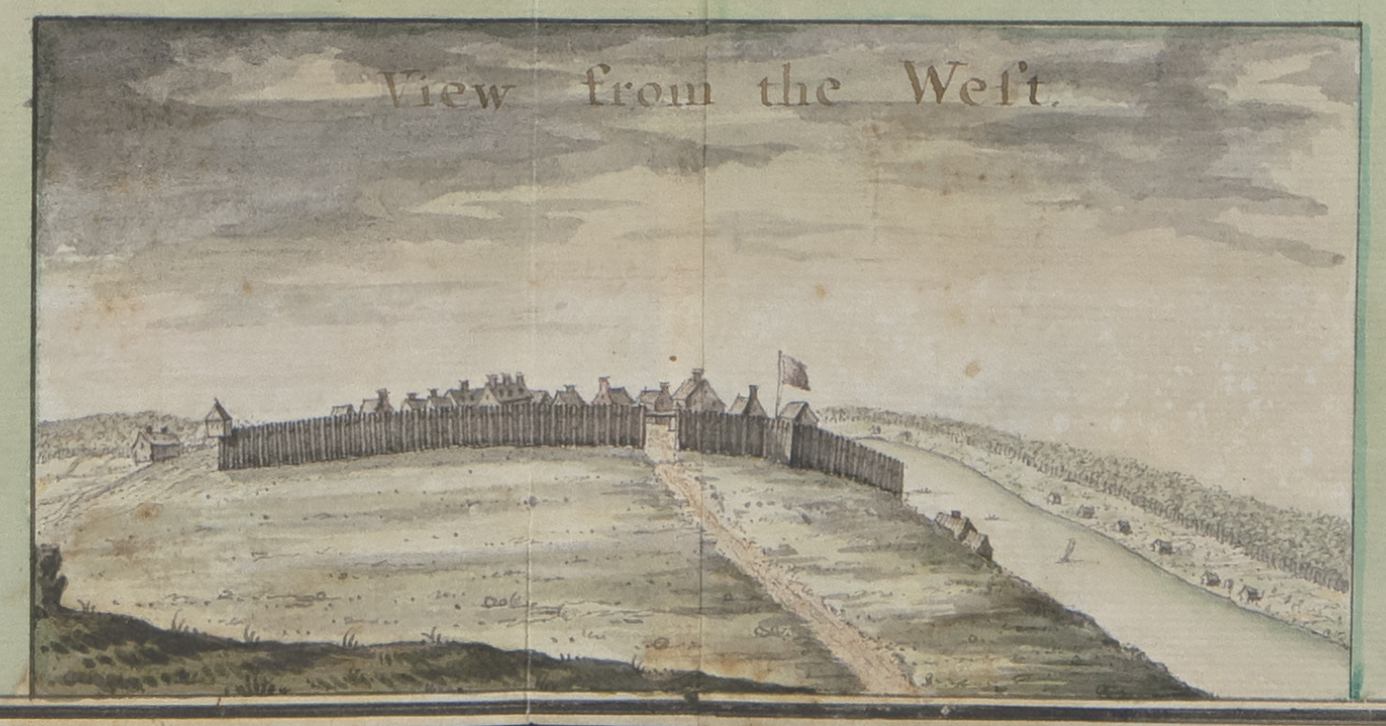

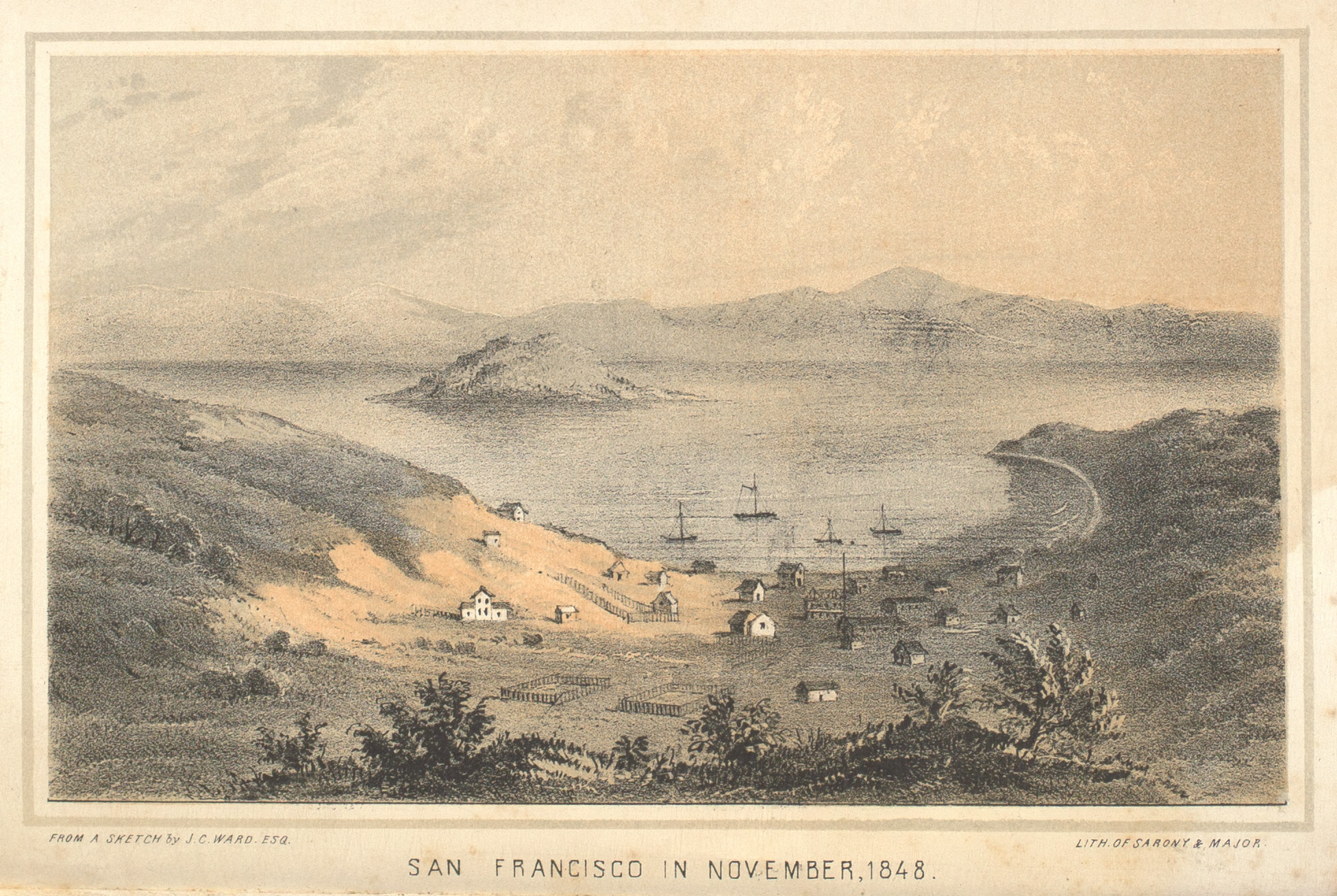

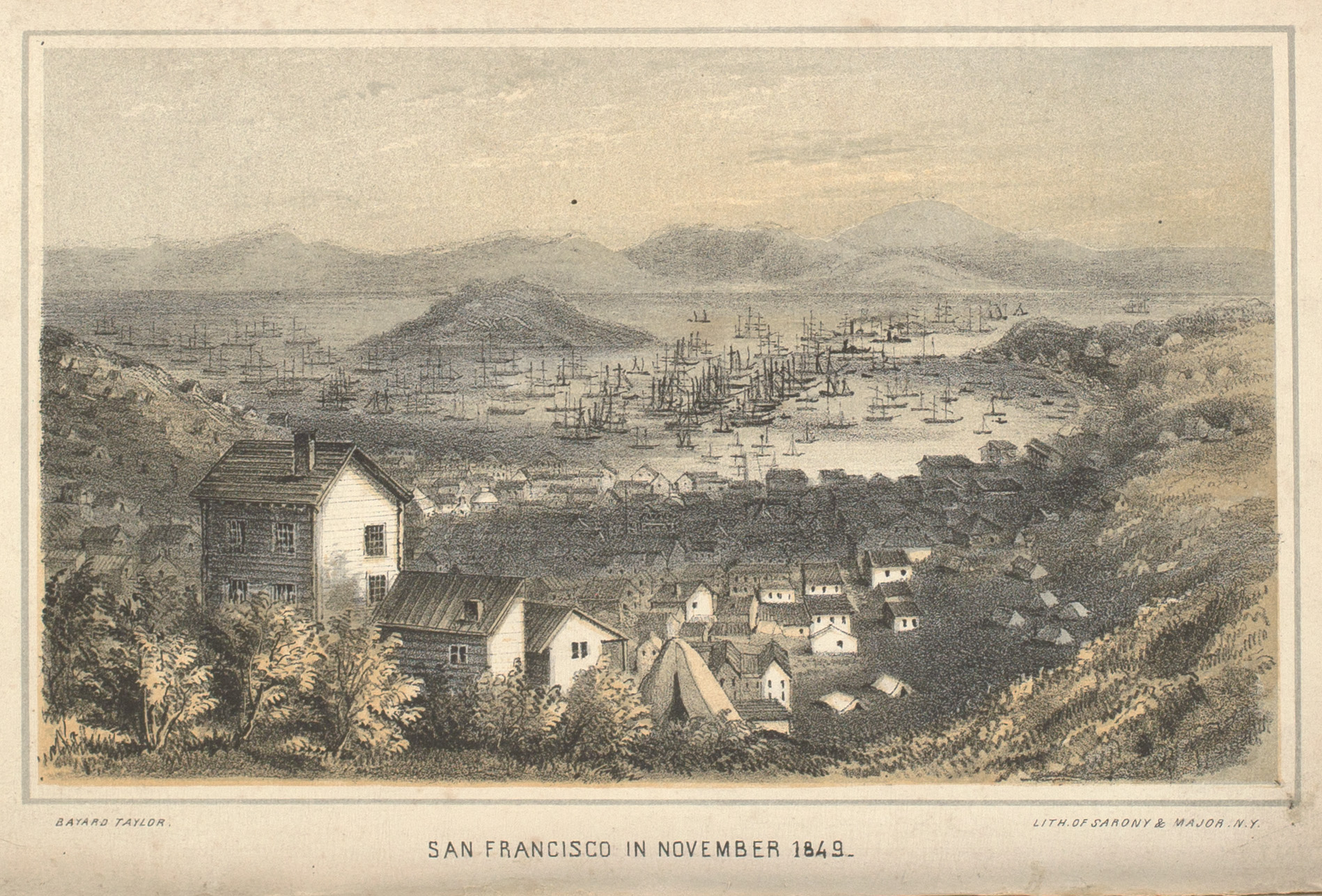

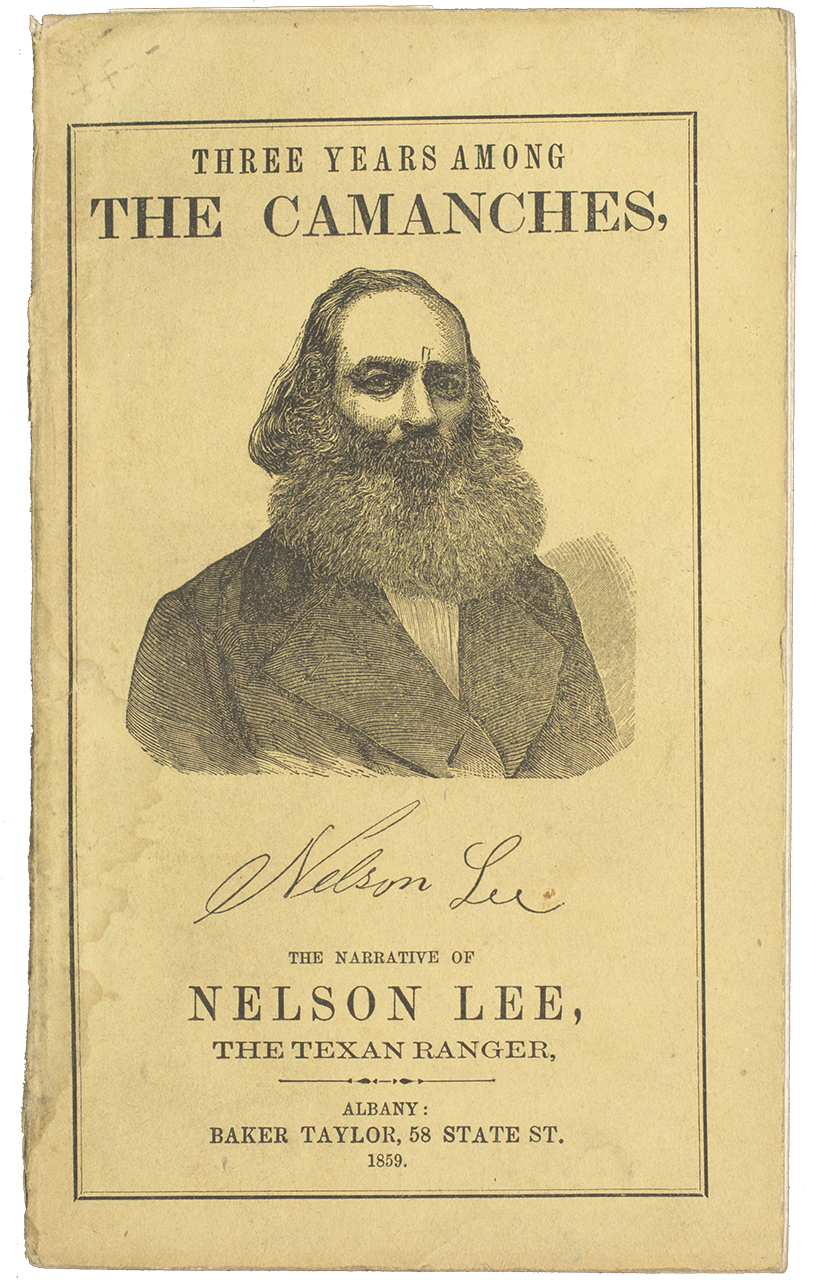

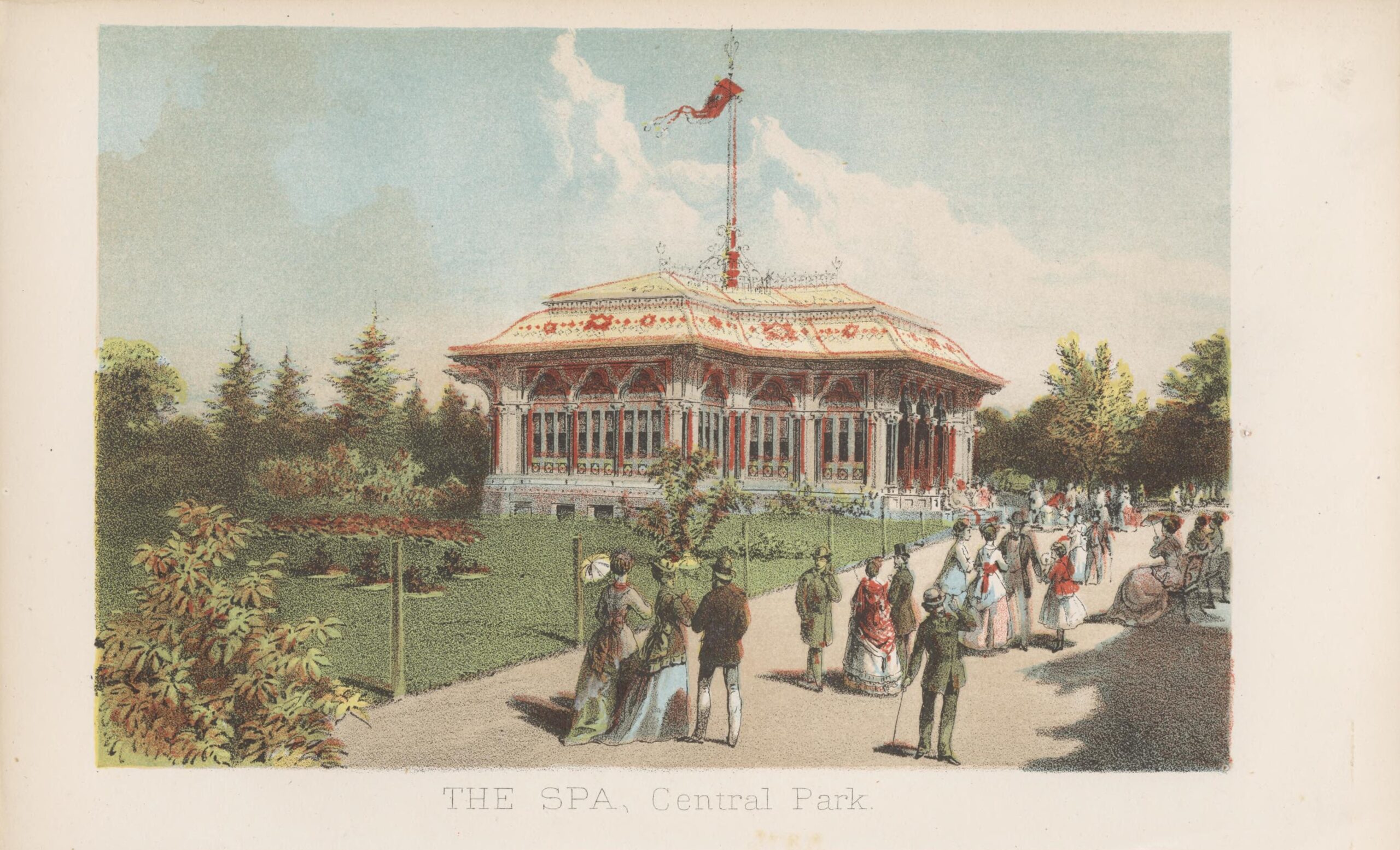

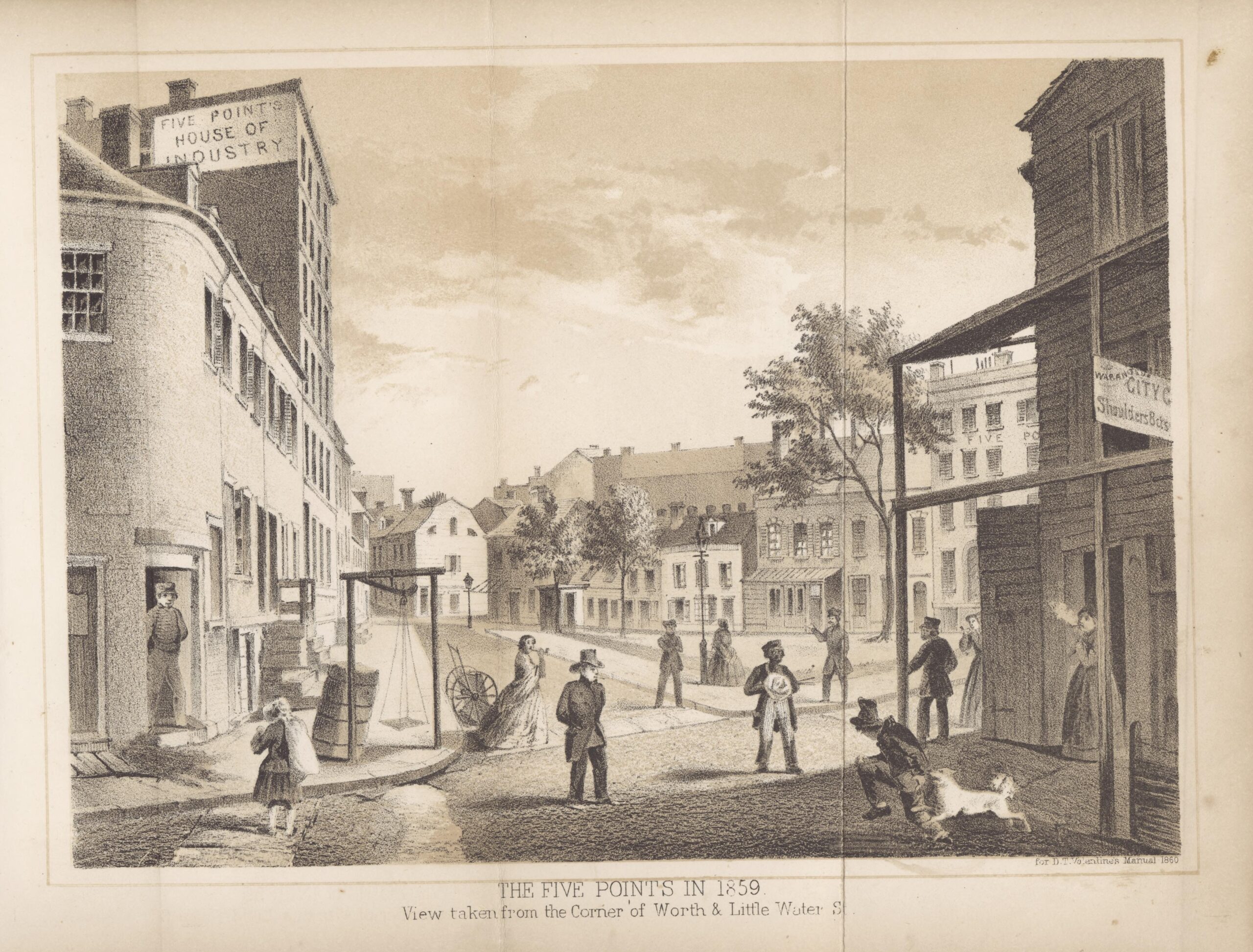

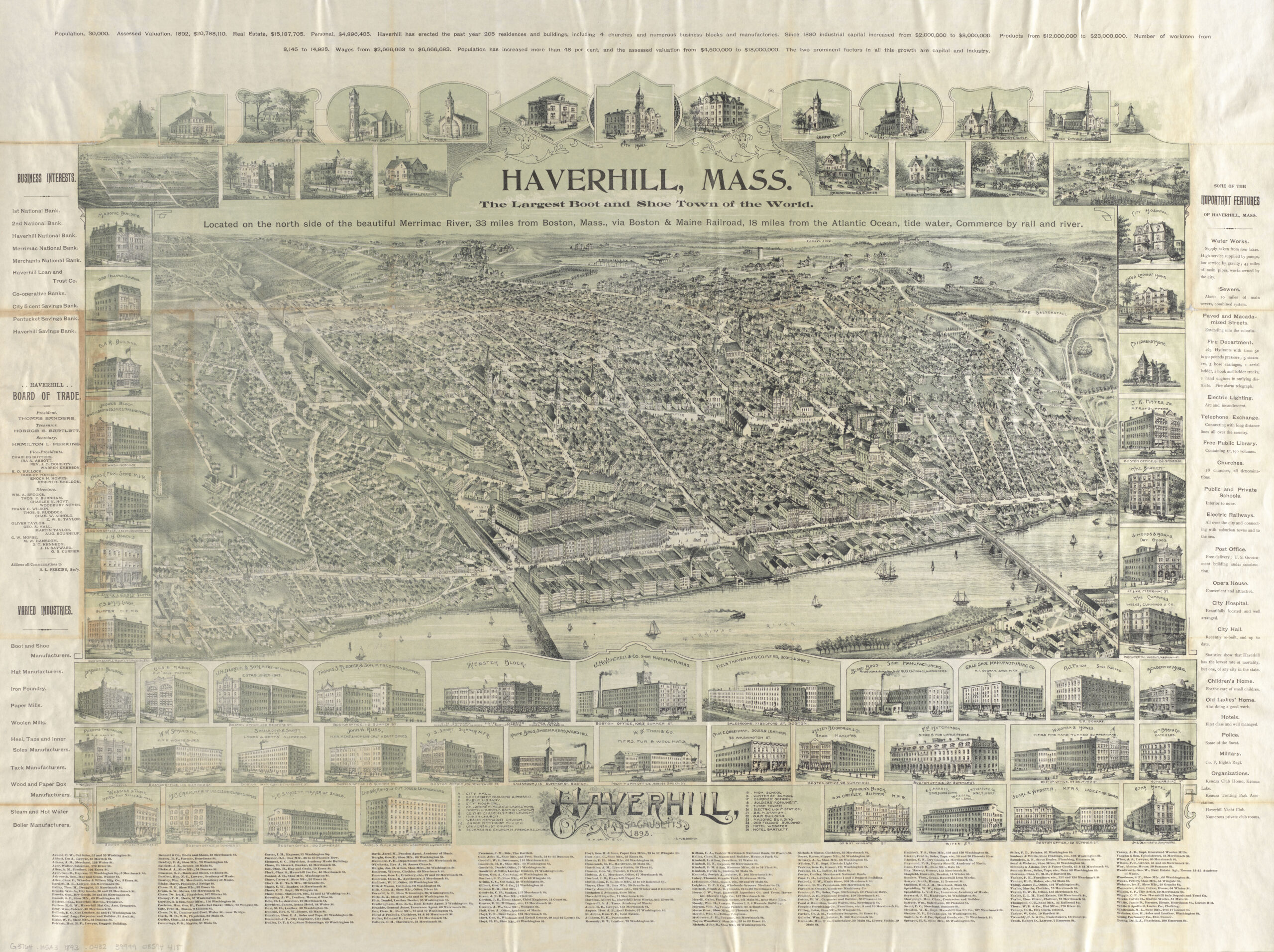

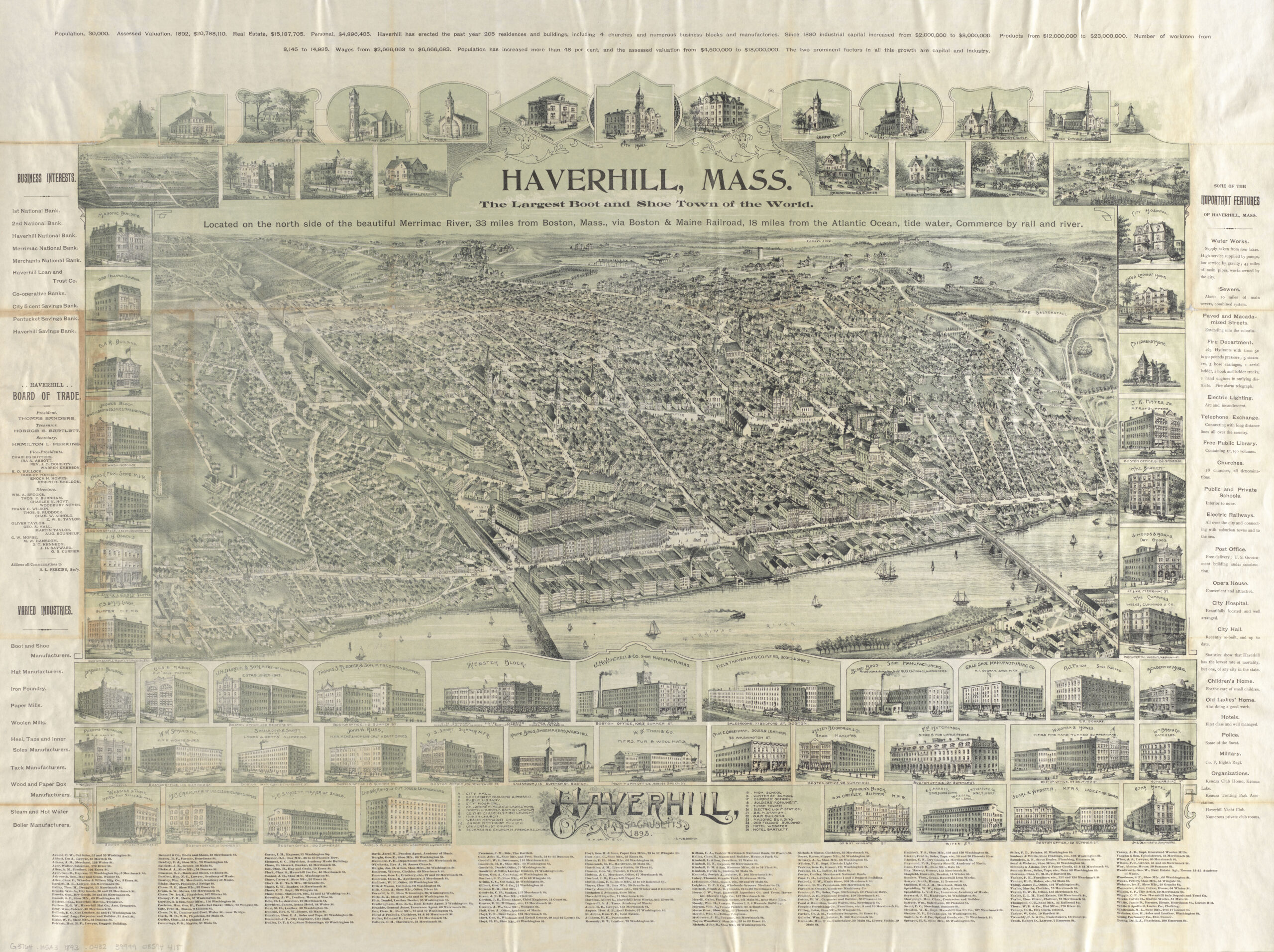

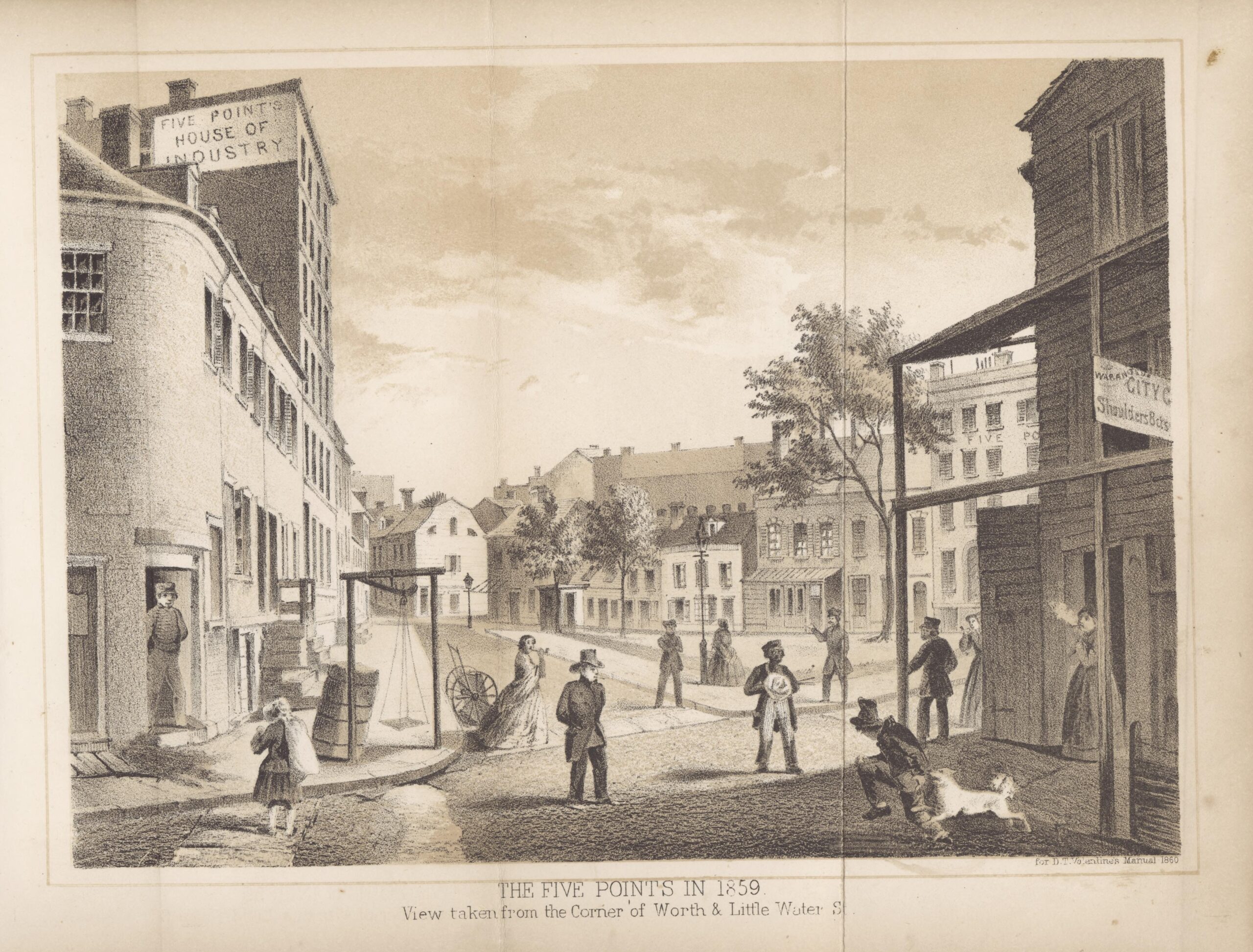

High on a rocky plateau overlooking a rich valley toward mountains beyond stood a group of Native Americans with their horses, attentively observing the scene spread out before them. Their dress identified them as indigenous: leggings and tunics, feathered headdresses, bows and quivers hanging from their shoulders. One of them sat by the horses and smoked a calumet, the sacred ceremonial pipe of personal prayer and communal rituals, used to mark the end of disputes, strengthen alliances, and insure peaceful relations. Their attention focused on the scene that unfolded below. A town nestled in the distance, its church steeple, industrial chimneys and substantial two- and three-storey buildings announcing a flourishing settlement. In the middle ground a suspension bridge allowed an oncoming train to cross the river, while a steam-powered paddle boat headed toward the town. In the near ground, directly below the rocky escarpment, a log cabin dominated space recently cleared, the tree stumps of an earlier wood still visible. A fence protected livestock while laundry waved from a line in the breeze.

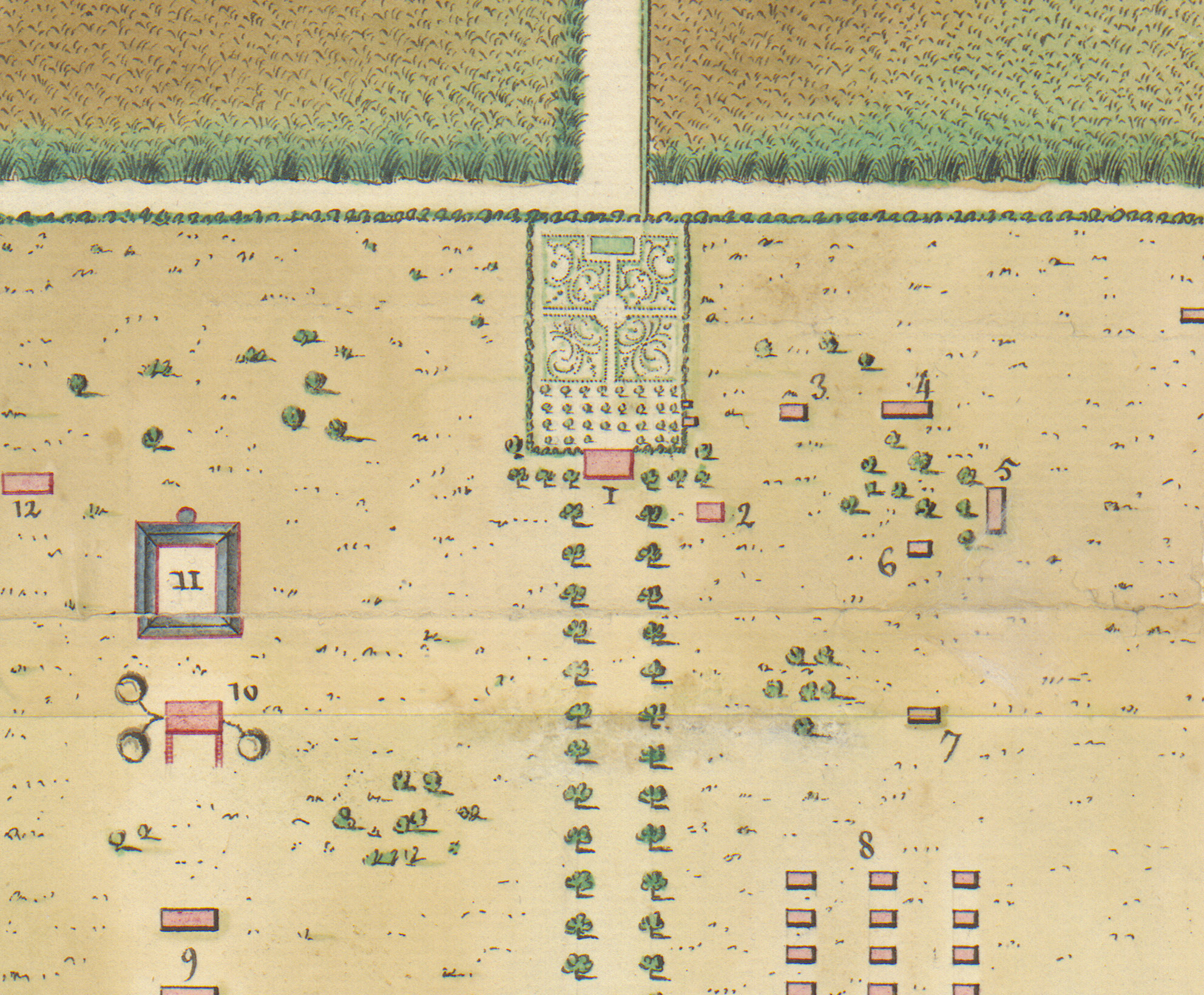

Colton’s Atlas of America was one of many publications of Joseph Hutchins Colton (1800–1893) who, from 1831, produced railroad maps, immigrant guides, folding pocket maps, large wall maps, and compilation atlases. He was aided by his son, George Woolworth Colton (1827–1901), whose map compilations comprised the contents of the Atlas of America. So what vision of America did the Vignette Title lead us to expect? Native Americans were placed boldly in the foreground and elevated above the landscape, encouraging us to expect some delineation of their own lands among the 63 maps of provinces, states, and territories inside the atlas. But we look in vain. Only on the maps of North America and the United States was a specifically Indian Territory, west of Arkansas, delineated and colored.

and Kanzas [sic]. On the detail from the map of Missouri, the Indian Territory may just be seen in the lower left corner; Native American names were printed in faint capital letters; and the distinctive pattern of township and range sections came to an abrupt stop at the state line, where the “West” began.

The Indian Territory, barely present in the Atlas of America, resulted from the The Indian Removal Act of 1830, whose purpose was described by President Andrew Jackson as “. . . the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes have accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes also to seek the same obvious advantages.”

Forests gone and hunting grounds lost. Those are the “obvious advantages” observed by the Native people on the rock in the Title Vignette.

Who created this subversive image? The vignette is signed “C.E. Doepler del[ineavit = designed it]” and “C. Wise sc[ulpsit = engraved it]”. C. Wise, the engraver, remains unidentified though his artisanal skills are clear. Carl Emil Doepler (1824–1905), on the other hand, was a German artist resident in New York City in the 1850s. Born in Warsaw, Poland, and trained as an artist in Dresden and Munich, he arrived in the city in 1849 to work as an illustrator for the publishers Harper and Brothers and G.P. Putnam, among others, for whom he created numerous images for children’s books and popular histories. His work address at Harper and Brothers at 82 Cliff Street in downtown Manhattan was only a few blocks away from 172 Williams Street where Joseph Hutchins Colton maintained his publishing house.

Doepler did not stay in New York; he returned to Germany by 1860 where he taught costume design in Weimar and became the costume designer for the city’s theater. He is probably best known for the costumes he designed for early productions of Richard Wagner’s Das Ring des Nibelungen, the great opera cycle concerning mythic Teutonic gods. Doepler’s ideas for how these gods were dressed have influenced productions of the Ring cycle to the present day. The title vignette for Colton’s Atlas of America showed Doepler’s early interest in cultural representation through clothing. His later working methods on the Nibelungen costumes might tell us something about how he created the frontispiece for the Colton atlas. The German scholar Joachim Heinzle has described Doepler’s efforts to produce “historically correct” Germanic costumes through his research in museums and study of early Teutonic weaponry, jewelry, and clothing to achieve what he thought was an accurate presentation of the mythic characters in Wagner’s opera.

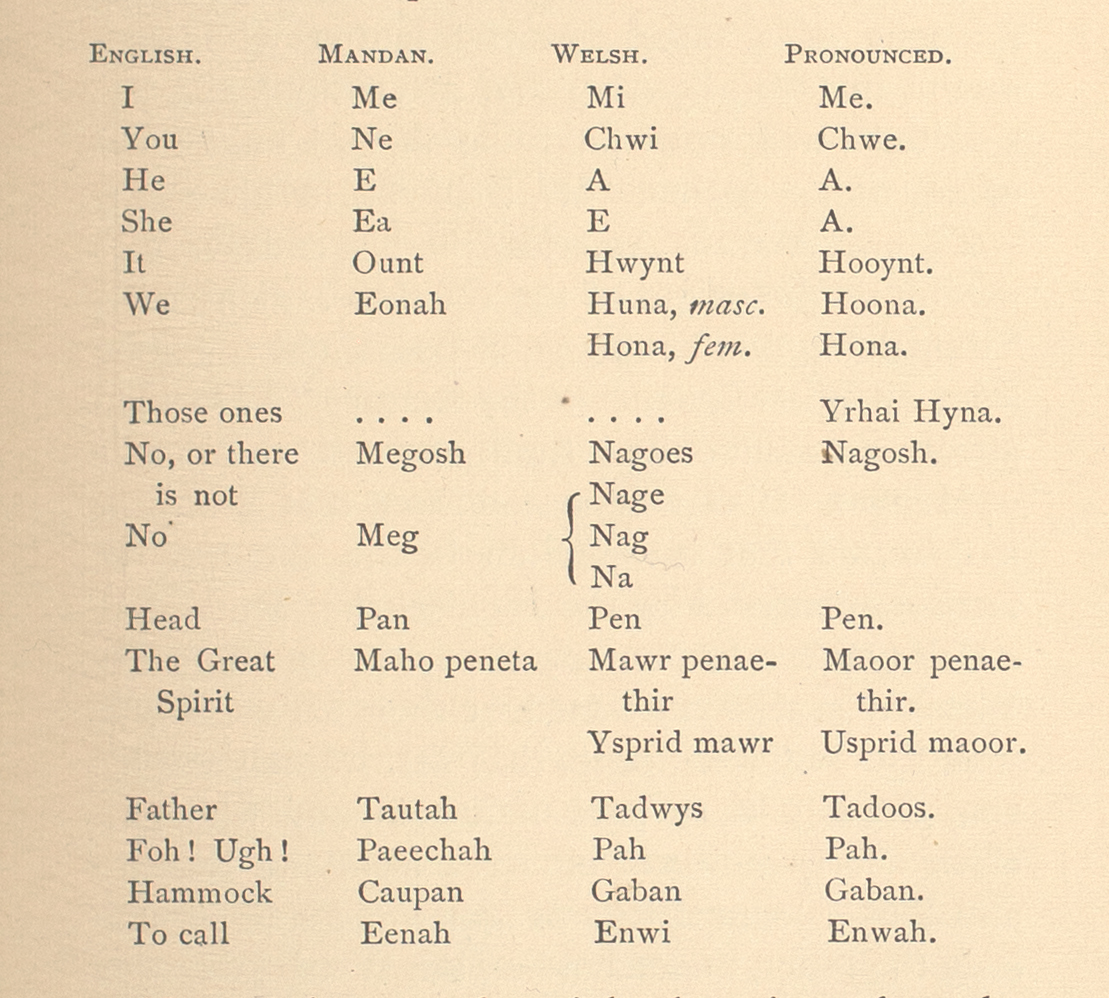

Doepler may also have been familiar with the work of Swiss artist Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) who was also well known in Germany for his artistic works. Bodmer accompanied Prince Alexander Philipp Maximilian zu Wied-Neuwied (1782–1867) on his trip from 1832 to 1834 through the interior of North America, traveling up the Missouri River into the heart of the Great Plains, deep in the homelands of the Mandan and Hidatsa, which were also the hunting and traveling regions for several other indigenous groups, such as the Sioux, Assiniboine, Cree, and Blackfoot. The Prince’s matter of fact descriptions of Native Americans, given without editorial nuance, were illustrated by Bodmer’s strikingly detailed colored images and published in German as Reise in das Innere Nord-Amerikas (Coblenz, 1839–41) and in English as Travels in the interior of North America (London, 1843–44). Their joint work created an archive of information for Native peoples of the northern Great Plains.

But what is the “civilization” invoked? Fences and farms, steam and railways, houses and tall buildings, the civilization of Manifest Destiny, a concept coined in detail by John Louis O’Sullivan, who summed it up in his article on the Oregon question in the newspaper, The Eastern State Journal (White Plains, NY, January 29, 1846): “And that claim [to Oregon] is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the Continent which Providence has given for the development [sic] of the great experiment of liberty and federative self government entrusted to us.” However, Manifest Destiny comes at a price. Inside the atlas, a geographical description of North America reveals the cost: “Of the American aborigines few remain. They have vanished from the land before the march of civilization.” In spite of its title, Doepler’s frontispiece, with its foregrounding of Native Americans, resists civilization and the claims of Manifest Destiny.

No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

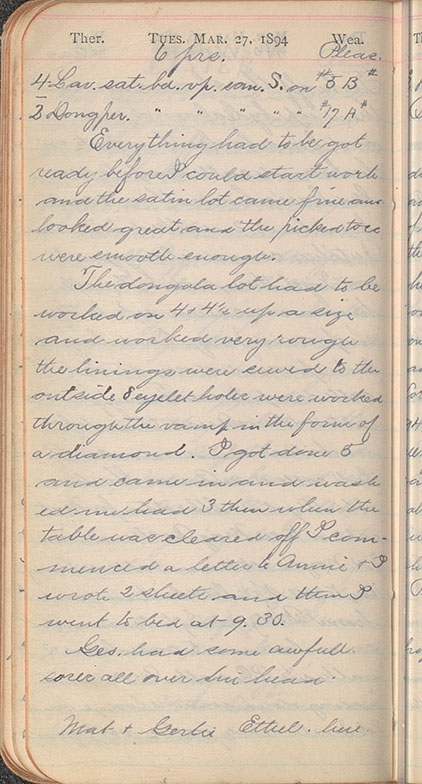

Marion Shipley’s classroom note evokes the delicious feeling of putting one over on the adults who regulate the daily life of children.

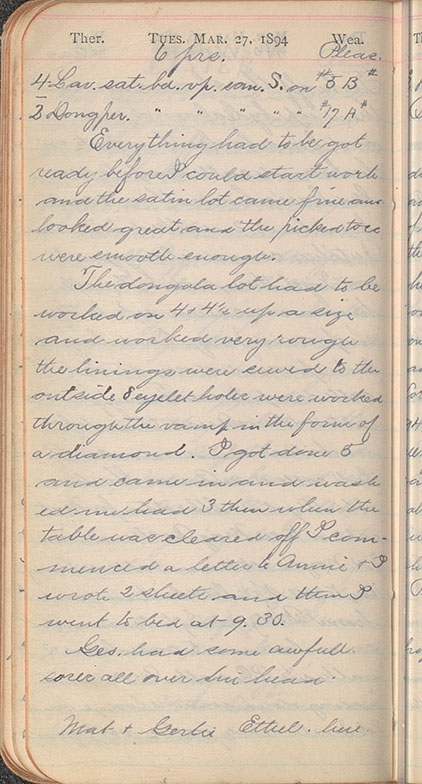

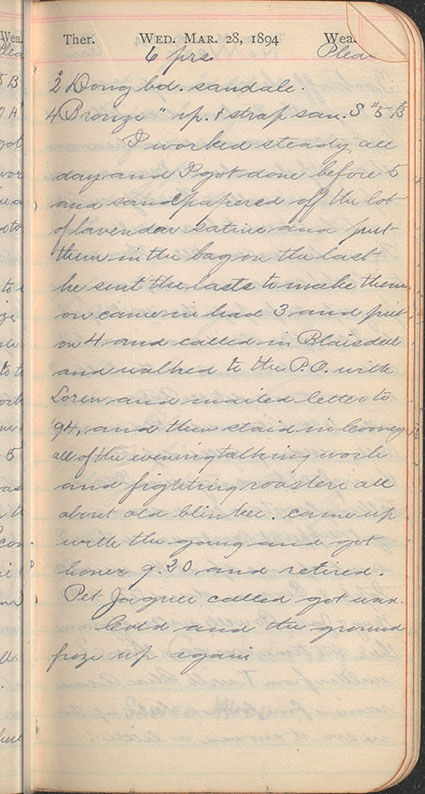

When I think about “Resistance” my mind automatically capitalizes the word, and I conjure visions of protests in the street, paint flung on fur coats, tea dumped in the harbor. I dwell on things with high stakes and big consequences, steeped in publicity and fevered debate. In short, I imagine worlds that feel beyond me in my (mostly) quiet library office, where I spend my days bedecked in a cardigan and generally avoiding conflict whenever possible. But in truth, our lives include more acts of resistance than we tend to realize. We might not break the rules, but we sure do bend them. Driving 75 miles per hour in a 70 zone. Reading in bed with a flashlight. Rolling into work five minutes late. Passing a note in class. Which brought to mind one of the favorite things I processed this past year, a stunning volume kept by Marion Shipley while a young teenager at the turn of the 20th century. She filled its pages with exquisitely collaged scenes, colored pencil drawings (including images of cat and elephant butts), newspaper clippings of dashing actors, embarrassing love letters, and several diary entries. The one dated June 7, 1907, is the one that captures my heart, as Marion celebrated having a substitute teacher. “We raised ‘ ’ (look at it upside down). We all drew pictures of each others’ backs and passed them around the class.” And in one of those rare moments of archival serendipity, Marion saved the passed note in her notebook and it stayed safely nestled between its pages all these years.

It’s a small slip of paper with the word “PASS” written on the outside, six pencil drawings of the back of classmates’ heads on the other. Holding it in your hand, noticing the braids and curls and ribbons in the girls’ hair, it feels like the note was passed to you. That you’re part of the gang of kids raising hell and anticipating the consequences the next day when the teacher returns. While the students also coordinated dropping their rulers all at the same time, caused kerfuffles in the coat room, and participated in other shenanigans that undoubtedly made the substitute teacher regret their choice to accept the assignment, it’s the artwork that stands as a visual reminder of the day, treasured and saved as a relic of youth’s ability to resist authority. It was a bright, funny, empowering moment that Marion held onto and passed along to us.

Students have long circumvented classroom rules and found ways to challenge the constrictions imposed upon them. The 1831 Regulations of the Springfield Female Seminary lists 33 strictures to carefully manage student behavior, or at least try to. It tells the students the appropriate way to hang their over-garments, how to sit and where, where food could be eaten, and forbids “boisterous talking and laughing” or “complaining of lessons, teachers, or each other.” The one that made me smile though, was the edict that “No pupil may speak with her fingers, or have any communication, written or symbolical, with another out of her own seat.” The fact that rules needed to be printed at all certainly indicates that students were whispering and passing notes and making signs to each other, complaining of teachers and laughing too loudly, just as Marion would some 70 years later.

While students in Marion’s class drew pictures and passed them desk to desk in order to reclaim degrees of power, others used the learning materials themselves to steal some time and agency. Richard M. White, a student at South Carolina College in 1813, wrote himself into being all over his copy of The Elements of Euclid, viz the First Six Books (Philadelphia: 1806), inscribing his name at least 37 times across the volume’s 518 pages. Doing so, the book is more his now than Euclid’s, forefronting his interpretation, his ownership, and his experience beyond all else. In the margin beside a particularly challenging exercise, he scrawled, “Is it not difficult to get knowledge? Yes it is out of Euclid. Ergo.” And elsewhere, in perhaps my favorite addition to the book, is an exquisitely simple and beautifully oversized “Oh Man” plastered across the top of the page alongside two hand drawn geometrical diagrams. You can imagine this student, frustrated and ink-stained, using the text itself to vent his exasperation. Perhaps like the Springfield Seminary, the students here were told that “complaining of lessons” was forbidden, but what if it was done silently in the empty space of the page?

“I have twenty eight pupils, most of them from thirteen to seventeen & some as wild as young colts. I am sometimes inclined to wish them very far away from me[.] [T]hey continue to keep me all the time busy & all the time tired.”

As much as students sought ways to press against rules, so too did teachers groan about having to enforce them. Classroom management is tough all around. As a very tired Philomena wrote to her friend, Caroline, of the class she was teaching in December 1837 in a letter found in our Education Collection, “I have twenty eight pupils, most of them from thirteen to seventeen & some as wild as young colts. I am sometimes inclined to wish them very far away from me[.] [T]hey continue to keep me all the time busy & all the time tired.” Comments like these, from the past as well as from the teachers in my own life today, make me wonder about how art and resistance might have eased some of the strain the instructors felt, too. Did they, too, find ways to complain about “lessons, teachers, or each other”?

Looking for signs of this, I paged through a notebook kept by an unnamed itinerant New England schoolmaster, where he compiled instructional exercises and explanations, helpful literary selections, and details about the classes he taught over the years. The leather cover is evocatively warped, raising visions of a water-logged teacher riding through the rain to his next class. Amid beautiful pen-and-ink trigonometry diagrams and surveying examples, lists of student names, and other teacher records, appears the ghostly outline of a left hand. I gently placed my hand over it, and my fingers ever-so-slightly reached beyond the ink mark.

Is this from a student’s hand, one of those listed in a roster elsewhere in the volume, who snuck in while it was unattended and inscribed themself into history? Or could this be our instructor, himself bored or distracted, avoiding grading or waiting for students to complete an assignment, who traced his own hand? Some things in the archive are unknowable, but the art, and the impulse to resist that can spur its creation, stand as testaments to the very human desire to make our mark, assert our power, and claim those pockets of uplifting joy in whatever small ways we can.

No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

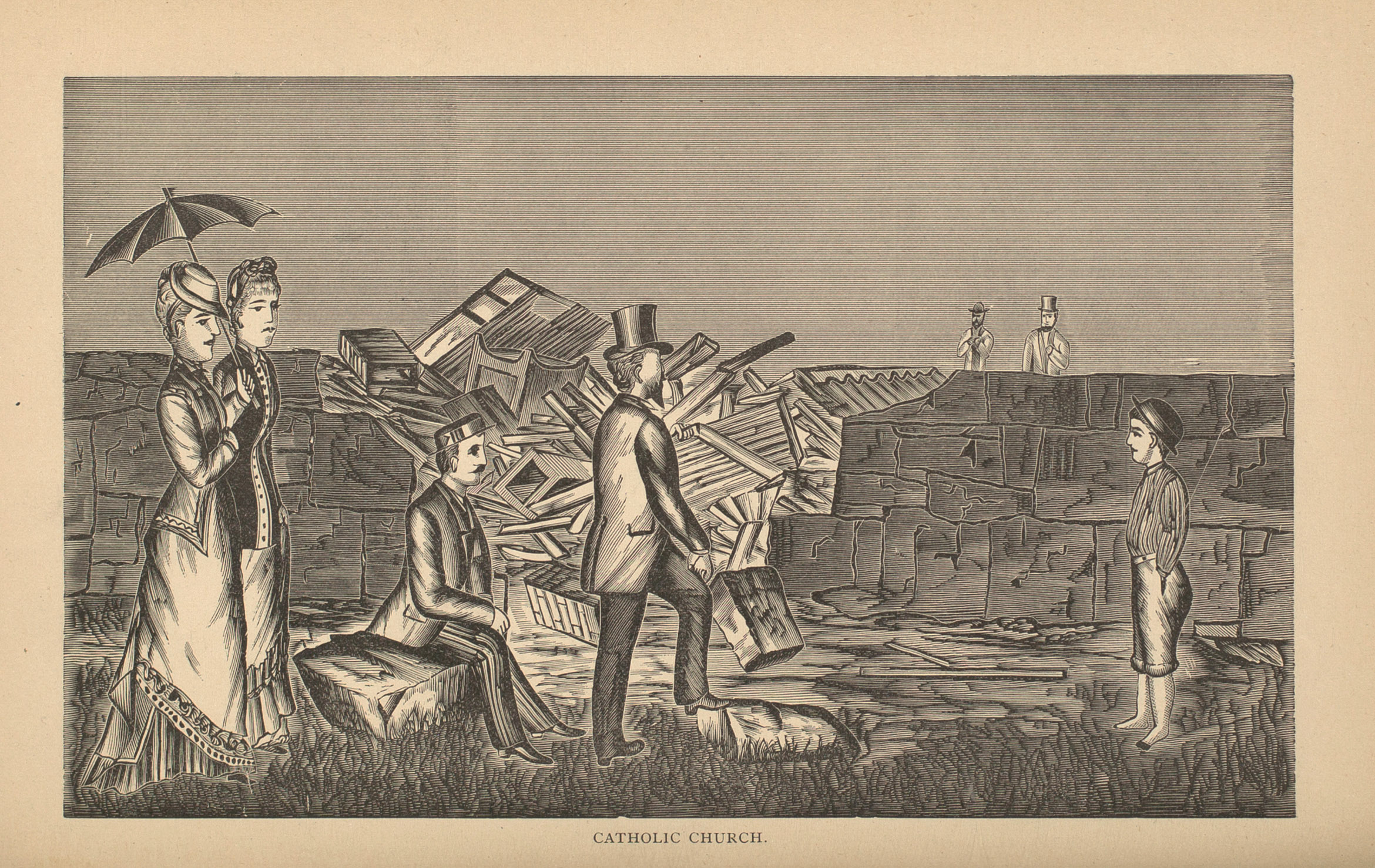

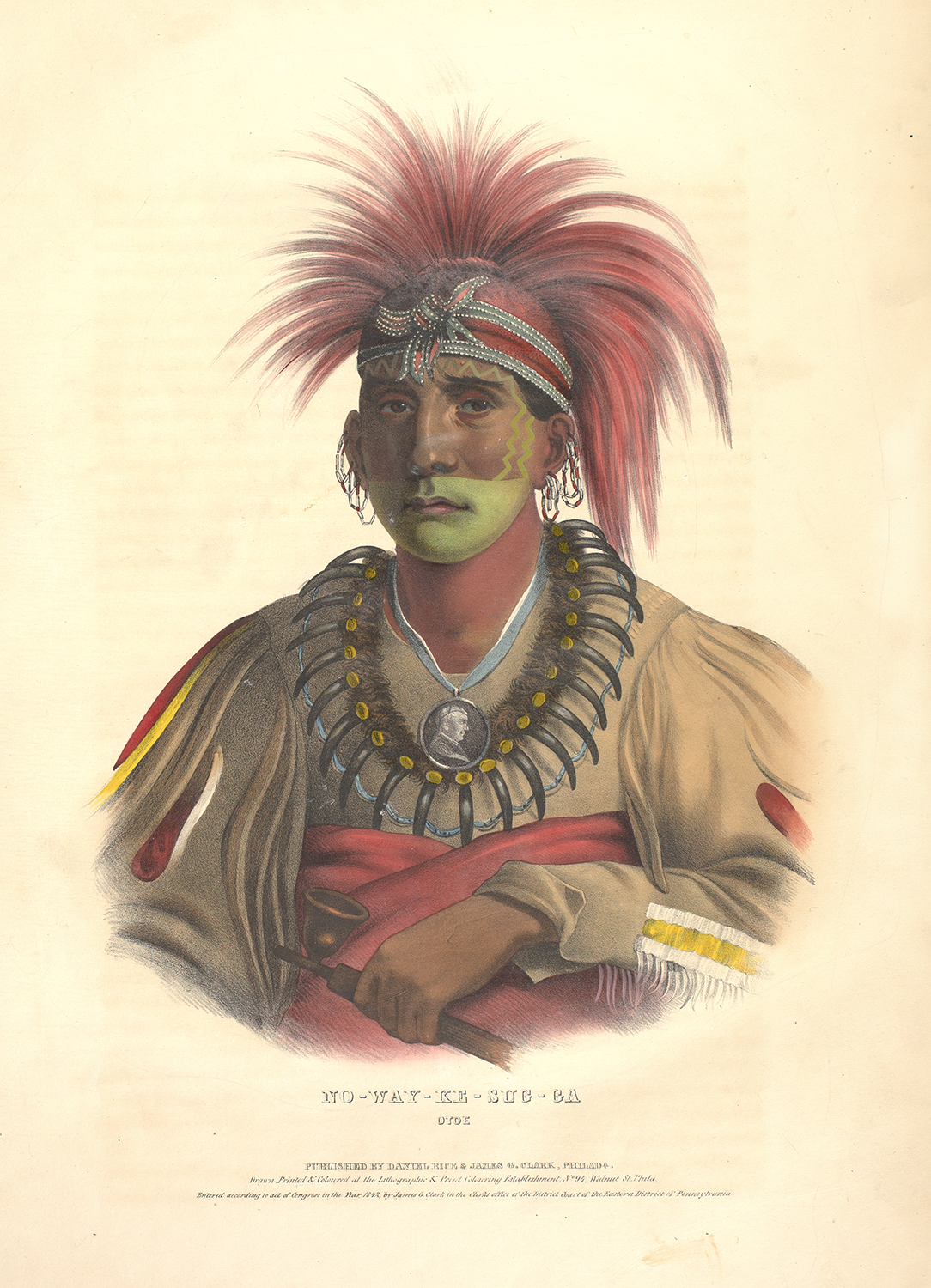

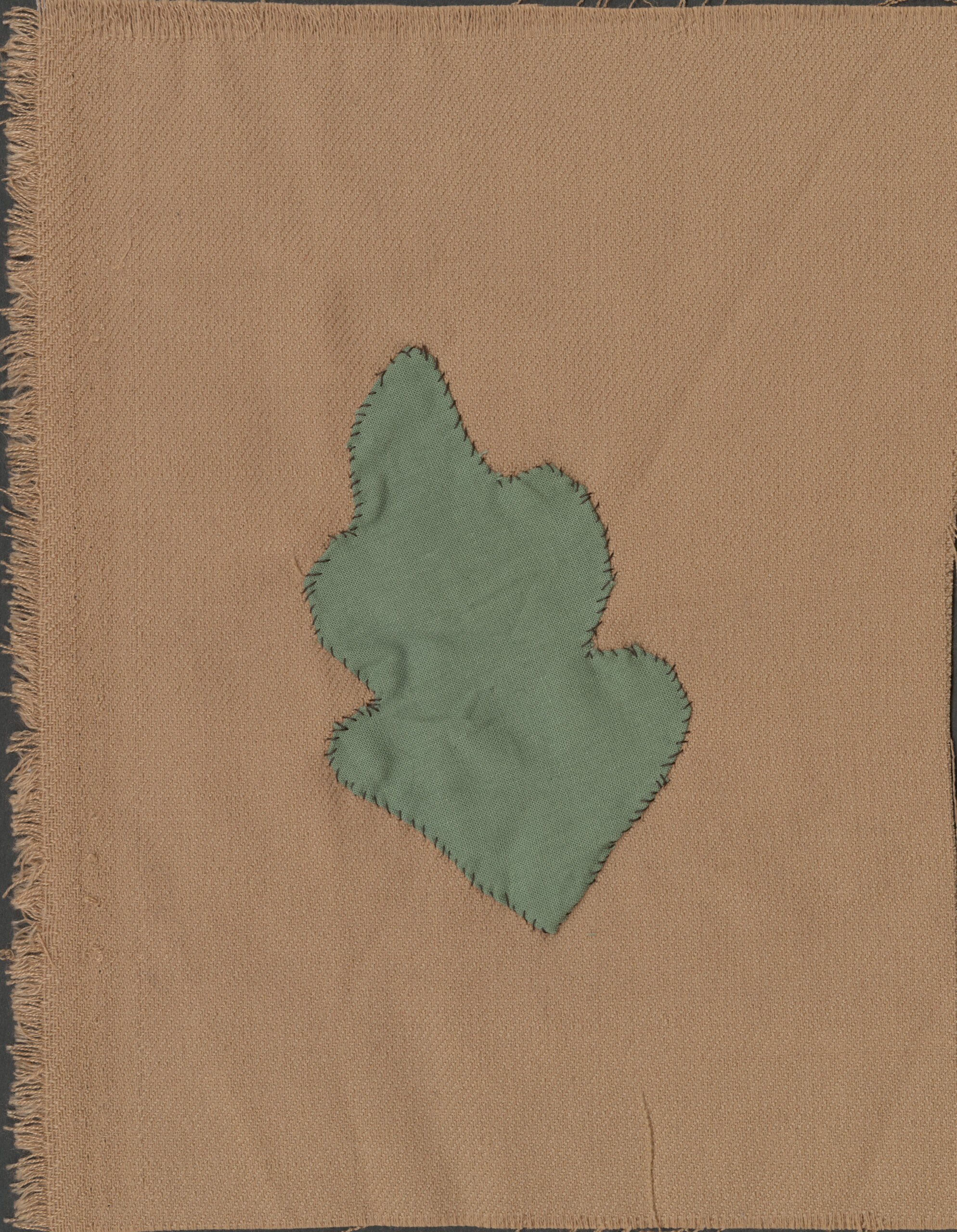

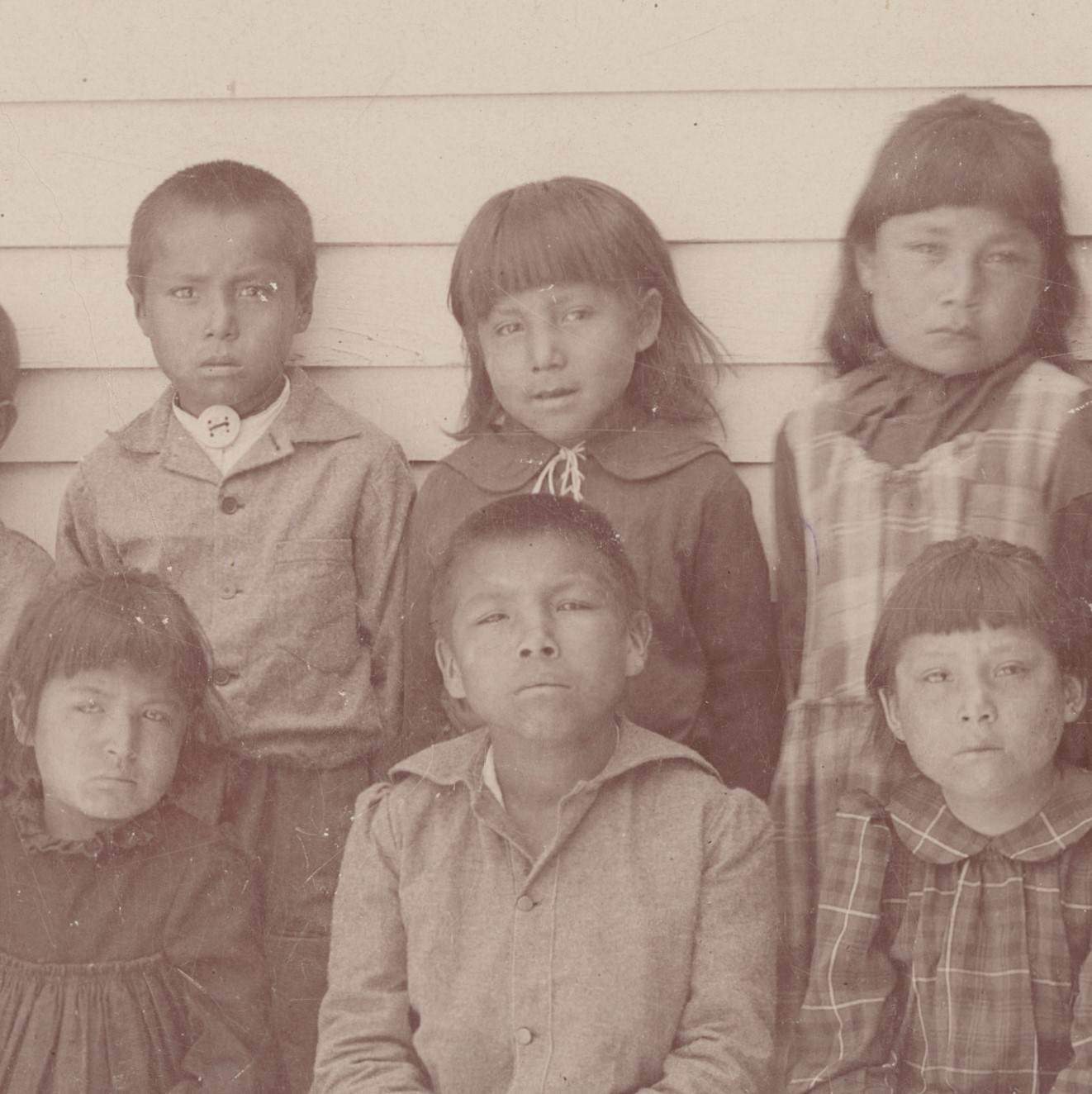

Several Native American religious movements originating over the course of the 19th century were formed in direct response to relentless oppression by the United States Government and land-hungry American settlers. Many of these movements evoked a return to an idealized pre colonized past, manifested through the revitalization of traditional ways of life. The ill-fated Ghost Dance movement that led to the tragic massacre of almost 300 Lakota people at Wounded Knee in December of 1890 is perhaps the most well-known example of this spiritual phenomenon. The Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography contains several images that shed light on another of these movements, the Faw Faw religion, and depicts the artistry of resistance that was demonstrated through its followers’ clothing.

In approximately 1890 while in the throes of a severe illness, an Otoe-Missouria man by the name of Waw-no-she (also known as William “Billy” Faw Faw) experienced a life-changing vision in which two young men appeared and reassured him that he would survive the sickness; a magnificent cedar tree then sprang from the earth accompanied by wild songbirds in fine voice. Faw Faw found deep spiritual meaning in this vision and began spreading the messages he interpreted from the experience. Before long, he had become the figurehead of a movement that preached the resurgence of traditional lifeways, the maintenance of a supportive community built on trust and kindness, and the rejection of pernicious influences wrought by exposure to Euro-American culture (especially land allotment and the consumption of alcohol).

The most important Faw Faw ceremony, the ritual planting of cedar trees, took place twice a year in July and December. A cedar tree was selected for uprooting and brought to a designated location, where it was planted at the center of an earthen lodge. Next, buffalo skulls were gathered and placed in the lodge alongside a drum. The participants then sang, danced, and smoked tobacco. Presents, including horses, were generously swapped and/or given to impoverished community members.

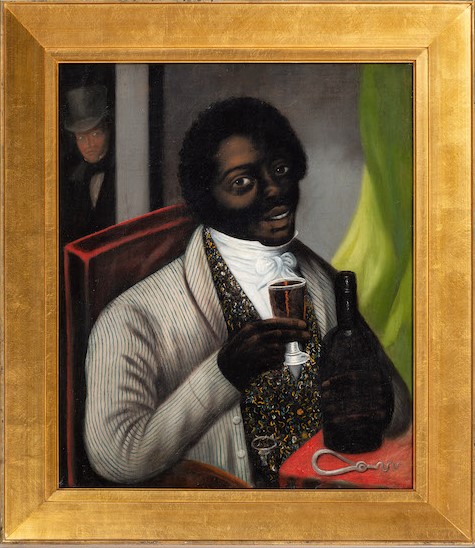

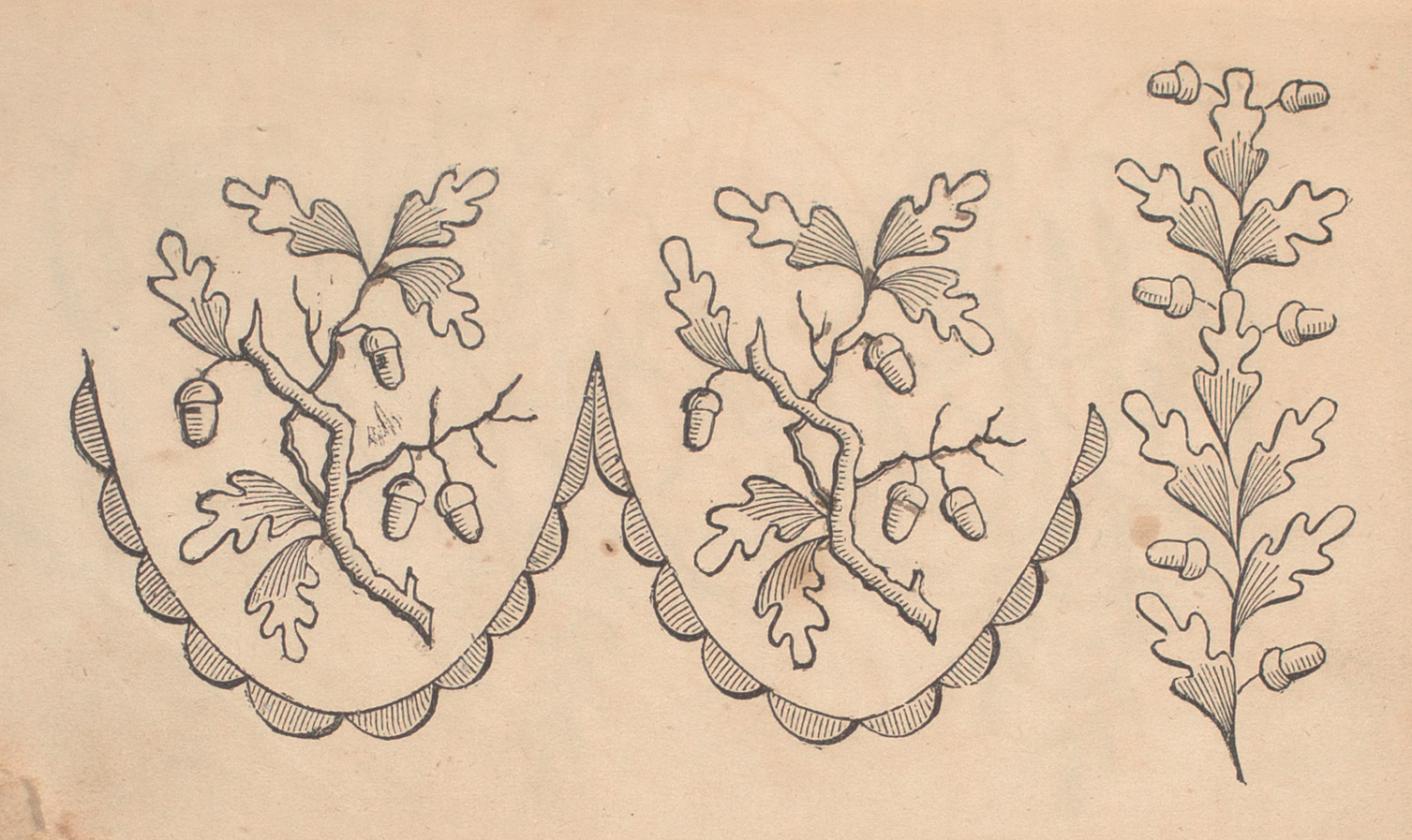

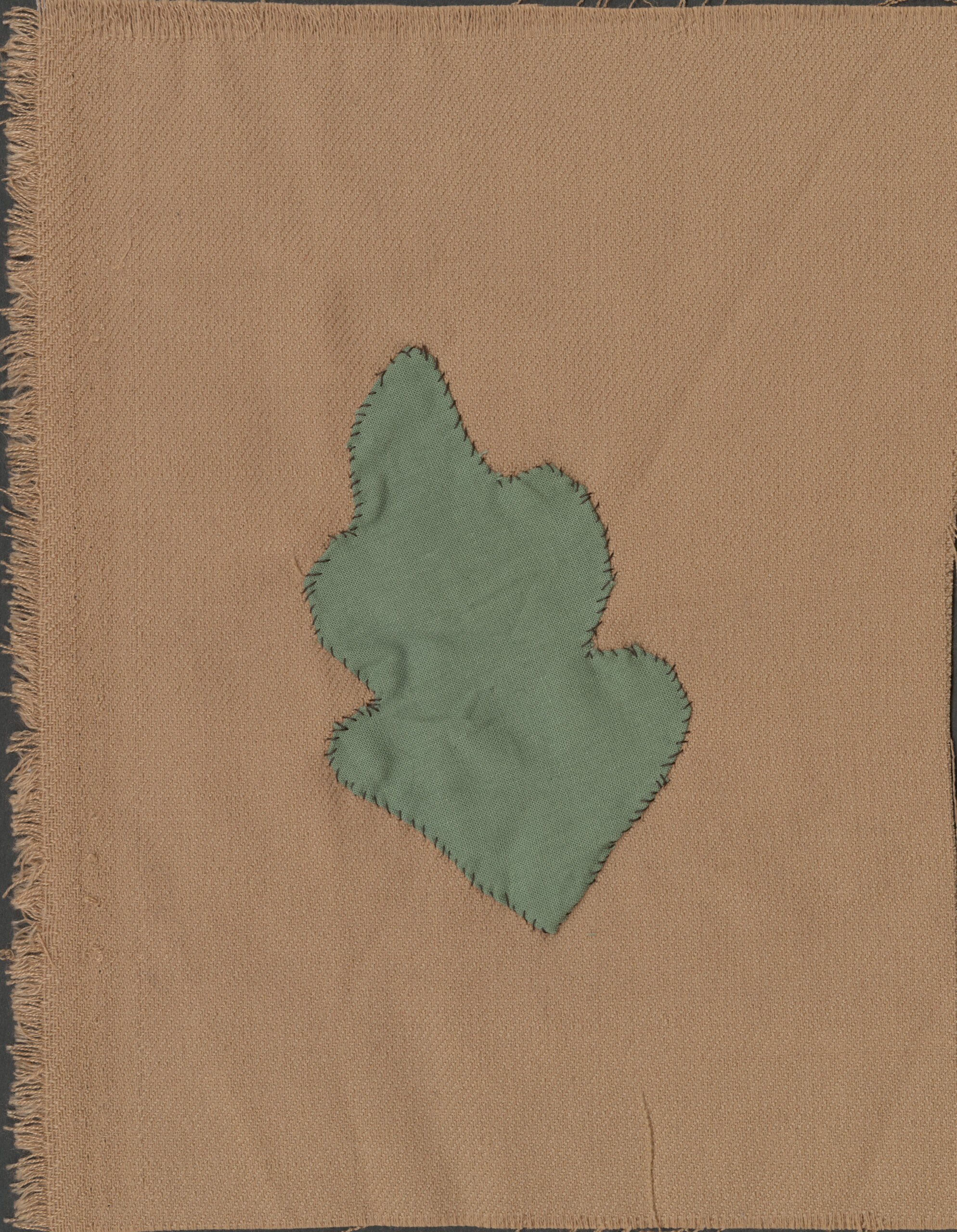

Adherents of the Faw Faw religion (which included members of the Otoe-Missouria, Ponca, Pawnee, Osage, and other tribes that had been relocated to Indian Territory) wore distinctive articles of clothing that incorporated symbols related to ritual aspects of the faith. Breechcloths and frock coats worn by men were often embellished with spectacular bead-embroidered designs including cedar trees, buffalo skulls, stars, birds, hands, crosses, and human figures posing with horses. By wearing clothing clearly associated with a movement that stood in opposition to the objectives of their colonizers, followers of Faw Faw openly signaled their beliefs through artistic expression. While the Faw Faw religion only lasted from around 1890 to 1895, its beautiful visual legacy remains in many material artifacts and photographs that survive to the present.

No. 58 (Fall/Winter 2023)

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

New Staff Members

Kayla Robinson joins the Development Department as the Marketing Coordinator and oversees social media, updates the website, and creates a variety of print and digital marketing pieces.

In a newly created position as a Development Generalist, Helen Harding fosters philanthropy through mailings, provides information and stewardship to donors, and helps plan special Centennial events.

Heather Alphonso lends her experience to the reception staff, greeting researchers and visitors and helping with administrative tasks.

Appointments

In July 2022, Clements Library Director Paul Erickson was officially announced as the president-elect of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, the primary scholarly society for historians studying the era between 1787 and 1860. His term will run from July 2023 to July 2024. He will be the first representative of a library or archive to hold the SHEAR presidency.

Welcome!

The Clements family welcomes its youngest member—Lucy Obata Goeman was born on February 23 to Emiko Obata Hastings, Curator of Books, and her husband Bill Goeman. Lucy’s own interest in books, like Lucy herself, is nascent but growing fast!

Clements Library Associates

The Quarto No. 15 in March of 1948 introduced the creation of the Clements Library Associates: “It is the University’s desire that our riches shall be more effectively shared with those who are concerned about American history and tradition. Therefore, the Regents of the University of Michigan, at their meeting of October 24, 1947 established The Clements Library Associates…”.

For the past 75 years, the Associates have fulfilled their original purpose of “increasing the collections and resources of the Clements Library and of broadening the scope, services, and usefulness of the Library.” Associates give of their collections, money, time, and intellect making the Clements the world-renowned library that it is today. Anyone who donates to the Clements Library is a member of the Clements Library Associates. To mark the 75th Anniversary, we celebrated on November 17, 2022, at the Clements Library.

Paul Erickson, Randolph G Adams Director of the Clements Library; Laurie McCauley, Provost; and Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman of the Clements Library Associates Board of Governors.

Debra Schwartz and Howard Brick peruse the pop-up exhibit highlighting acquisitions made possible by the Associates.

Carol Virgne, Randi Kawakita, Tsune Kawakita, and Charlotte Maxson.

Randolph G. Adams Director of the Clements Library

Paul J. Erickson

Committee of Management

Santa J. Ono, Chairman

Gregory E. Dowd, James L. Hilton, David B. Walters.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Board of Governors

Bradley L. Thompson II, Chairman

John R. Axe, John L. Booth II, Kristin A. Cabral, Candace Dufek, Charles R. Eisendrath, Derek J. Finley, Eliza Finkenstaedt Hillhouse, Troy E. Hollar, Martha S. Jones, Sally Kennedy, Joan Knoertzer, James E. Laramy, Thomas C. Liebman, Richard C. Marsh, Janet Mueller, Drew Peslar, Richard Pohrt, Catharine Dann Roeber, Anne Marie Schoonhoven, Harold T. Shapiro, Arlene P. Shy, James P. Spica, Edward D. Surovell, Irina Thompson, Benjamin Upton, Leonard A. Walle, David B. Walters, Clarence Wolf.

Paul J. Erickson, Secretary

Clements Library Associates Honorary Board of Governors

Peter Heydon, Chair Emeritus. Joanna Schoff.

Clements Library Associates share an interest in American history and a desire to ensure the continued growth of the Library’s collections. All donors to the Clements Library are welcomed to this group. The contributions collected through the Associates fund are used to purchase historical materials. You can make a gift online at leadersandbest.umich.edu or by calling 734-647-0864.

Published by the Clements Library

University of Michigan

909 S. University Ave. • Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109

phone: (734) 764-2347 • fax: (734) 647-0716

Website: https://clements.umich.edu

Terese M. Austin, Editor, [email protected]

Designed by Savitski Design, Ann Arbor

Regents of the University

Jordan B. Acker, Huntington Woods; Michael J. Behm, Grand Blanc; Mark J. Bernstein, Ann Arbor; Paul W. Brown, Ann Arbor; Sarah Hubbard, Okemos; Denise Ilitch, Bingham Farms; Ron Weiser, Ann Arbor; Katherine E. White, Ann Arbor.

Santa J. Ono, ex officio

Nondiscrimination Policy Statement

The University of Michigan, as an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer, complies with all applicable federal and state laws regarding nondiscrimination and affirmative action. The University of Michigan is committed to a policy of equal opportunity for all persons and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, marital status, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression, disability, religion, height, weight, or veteran status in employment, educational programs and activities, and admissions. Inquiries or complaints may be addressed to the Senior Director for Institutional Equity, and Title IX/Section 504/ADA Coordinator, Office of Institutional Equity, 2072 Administrative Services Building, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1432, 734-763-0235, TTY 734-647-1388, [email protected]. For other University of Michigan information call 734-764-1817.

![gr-uncat-[clements library] leon makielski ca. 1920s](https://clements.umich.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/gr-uncat-clements-library-leon-makielski-ca.-1920s-scaled.jpg)

On the Cover

Leon Makielski (1885 – 1974) was an artist from southeast Michigan who specialized in landscapes and portraits. He developed an Impressionist style while studying in Paris, and later taught at The University of Michigan School of Art & Design.

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

As people who work in a rare book library, my colleagues and I are all by nature completists, which is to say that the most nerve-wracking question on our minds as we contemplate our centennial celebrations is: What if we leave something out? But we can’t tell every story of every research discovery in the library, we can’t show you every picture of every source that we love (not if you want to be able to actually lift this issue of The Quarto). What I can do, though, is point to some highlights in this wonderful issue, and to some events in the coming year, that will show how we are thinking about our centennial—as a celebration of a storied past, but also as a gateway to a new century.

Other articles in this issue highlight the work that members of the Clements Library staff have done over the previous century. Julia Miller shows how both collectors and scholars have become more interested in examining original bindings—as opposed to embellished re-bindings— of early American books, an area where we have been focusing some of our acquisitions energy. And Angela Oonk describes the crucial role that building connections with donors has made in sustaining the Clements for its first hundred years.

Everything that we do at the Clements—and everything that we plan to do—is based on our collections, and on their continued growth. And our commitment to the importance of the in-person encounter with primary sources from the American past is stronger than ever, as we emerge from the past three years where the pandemic made those encounters difficult for many researchers. Technology now permits readers on the other side of the world to see manuscripts, photographs, and books from the Clements collection as clearly as they could in the Avenir Room, and we will continue to broaden this mode of access. We will also work to make the library a more welcoming place for an increasingly diverse group of students, scholars, and other visitors. All of the changes that you see when you visit the library over the coming year are intended to help us better tell our story, to let the community at the university and beyond know what we do and what we stand for. We remain committed to preserving the materials in the Clements collection for future generations, but we are also committed to putting them to use for the generation that’s here right now. It’s going to be an exciting second century.

— Paul Erickson

Randolph G. Adams Director

William L. Clements Library

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

The Centennial is a celebration of the William L. Clements Library, but it is also a story of the philanthropy of the people who have bolstered the building, collections, and programs through their generosity. This, of course, starts with Mr. Clements himself. Influenced by U-M Professors Thomas M. Cooley and Moses Coit Tyler, Clements had a love of American history and culture that led to his collection and eventual donation of materials. His vision included the funds to build a magnificent facility to house the collection designed by Albert Kahn. While these gifts were extraordinary, Mr. Clements also participated in a variety of other philanthropic causes, but did not offer an explanation behind his gifts. We lack insight into the reasons behind his philanthropy and what influenced his donations—whether it was part of the culture of the time, a sense of duty, or other personal or moral imperative.

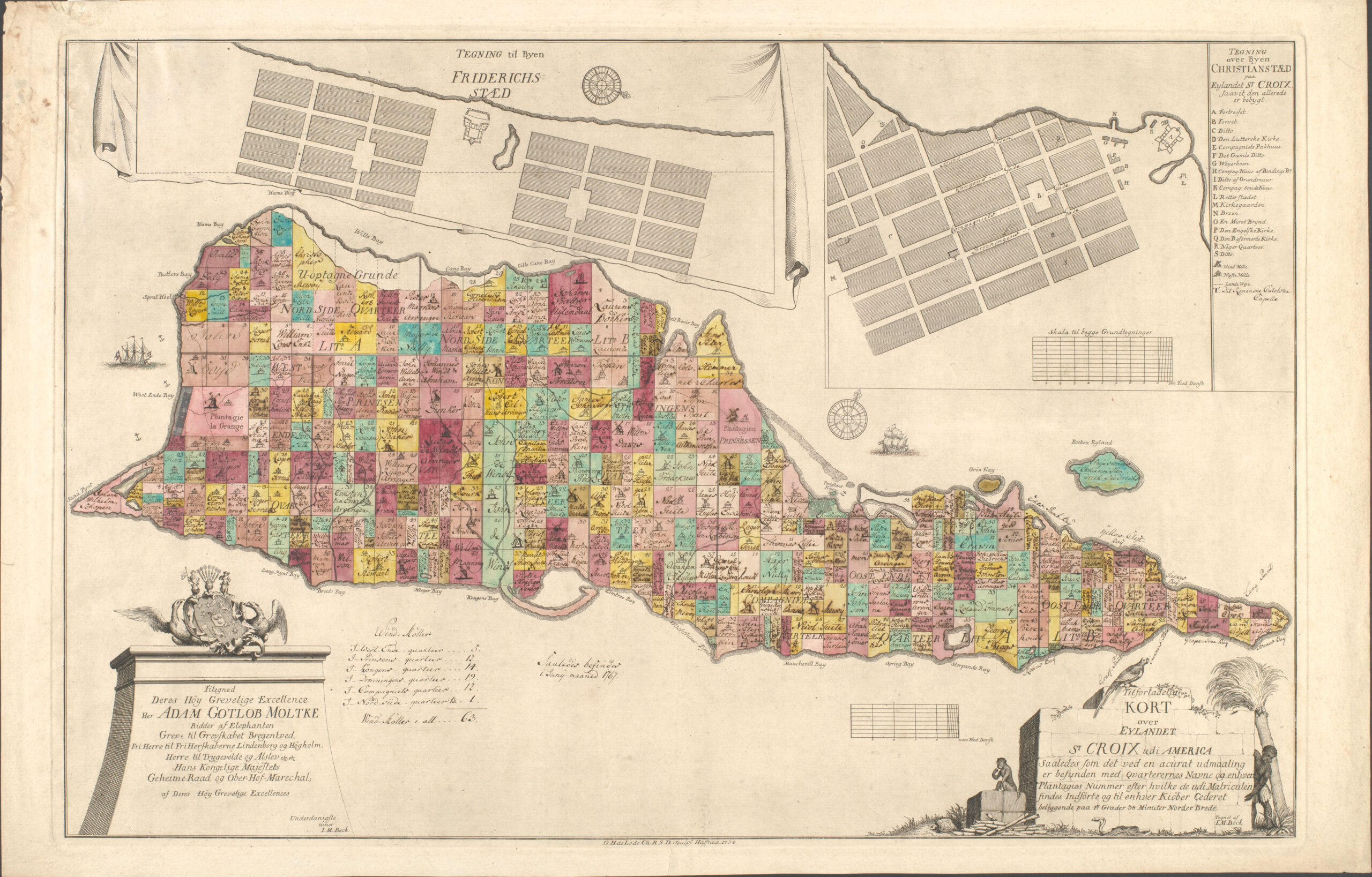

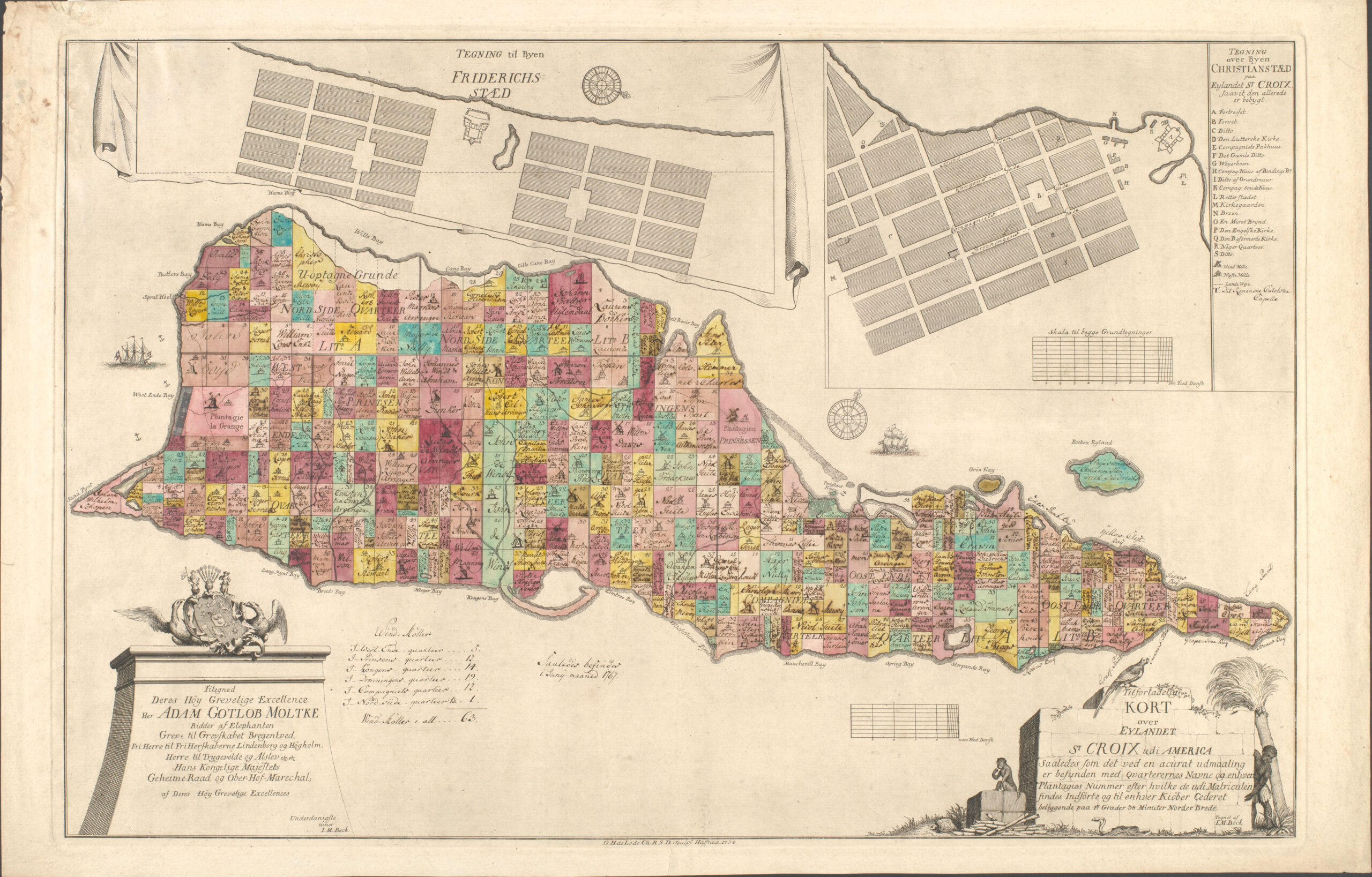

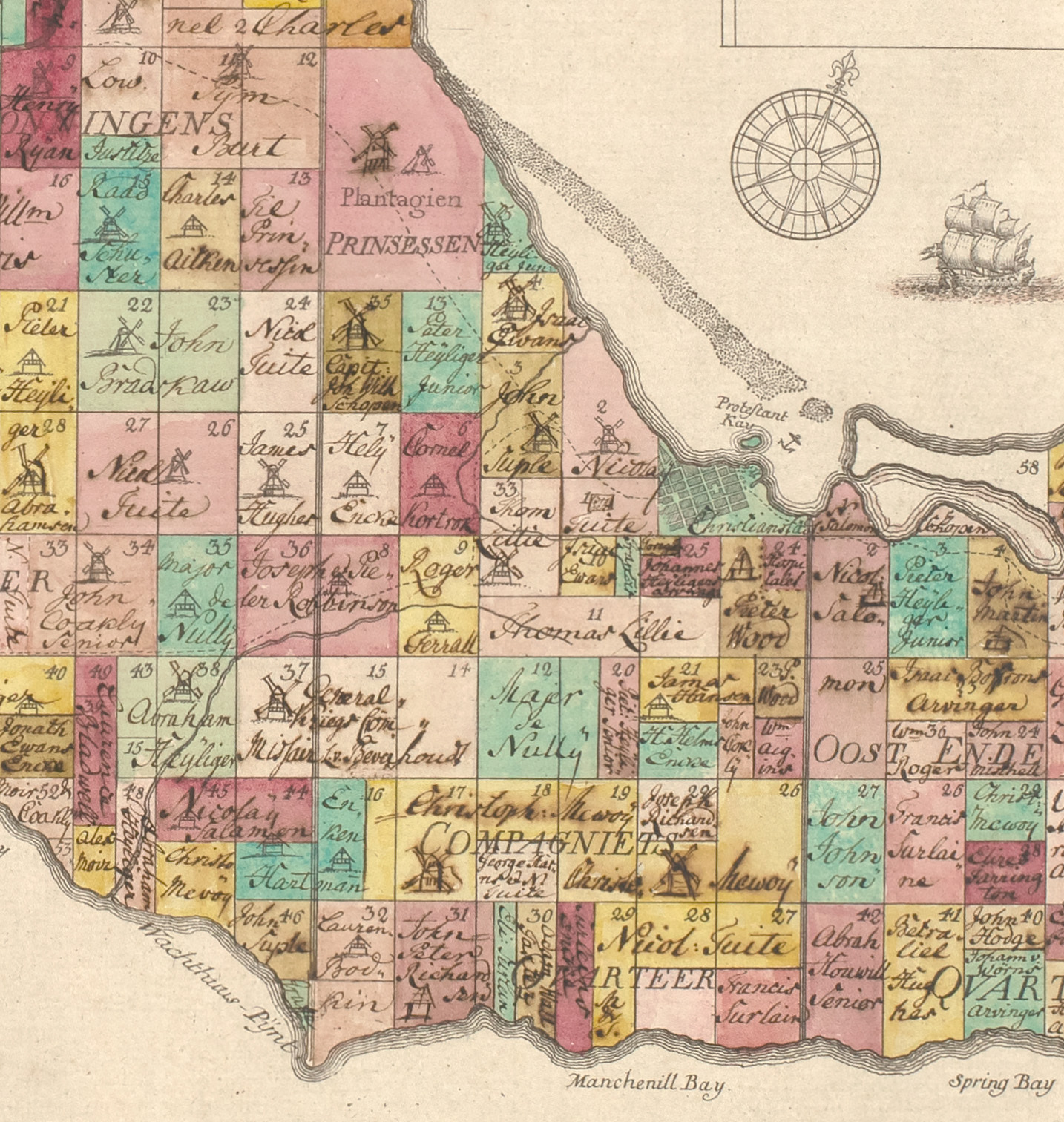

Jens Michelsen Beck, Tilforladelig Kort over Eylandet St. Croix Udi America ([Copenhagen], 1754)

In November we celebrated the 75th anniversary of the Clements Library Associates (see sidebar). In addition to a party to mark the celebration, I also hosted 2022 Norton Strange Townshend Fellow Amanda Moniz on the online program Clements Bookworm to discuss her research into philanthropy. One hundred years ago the Clements Library didn’t have any professional fundraising staff let alone research fellows looking for evidence of philanthropy in the archives. The beautiful thing about the archives is that there are innumerable layers of information awaiting new questions to be asked.

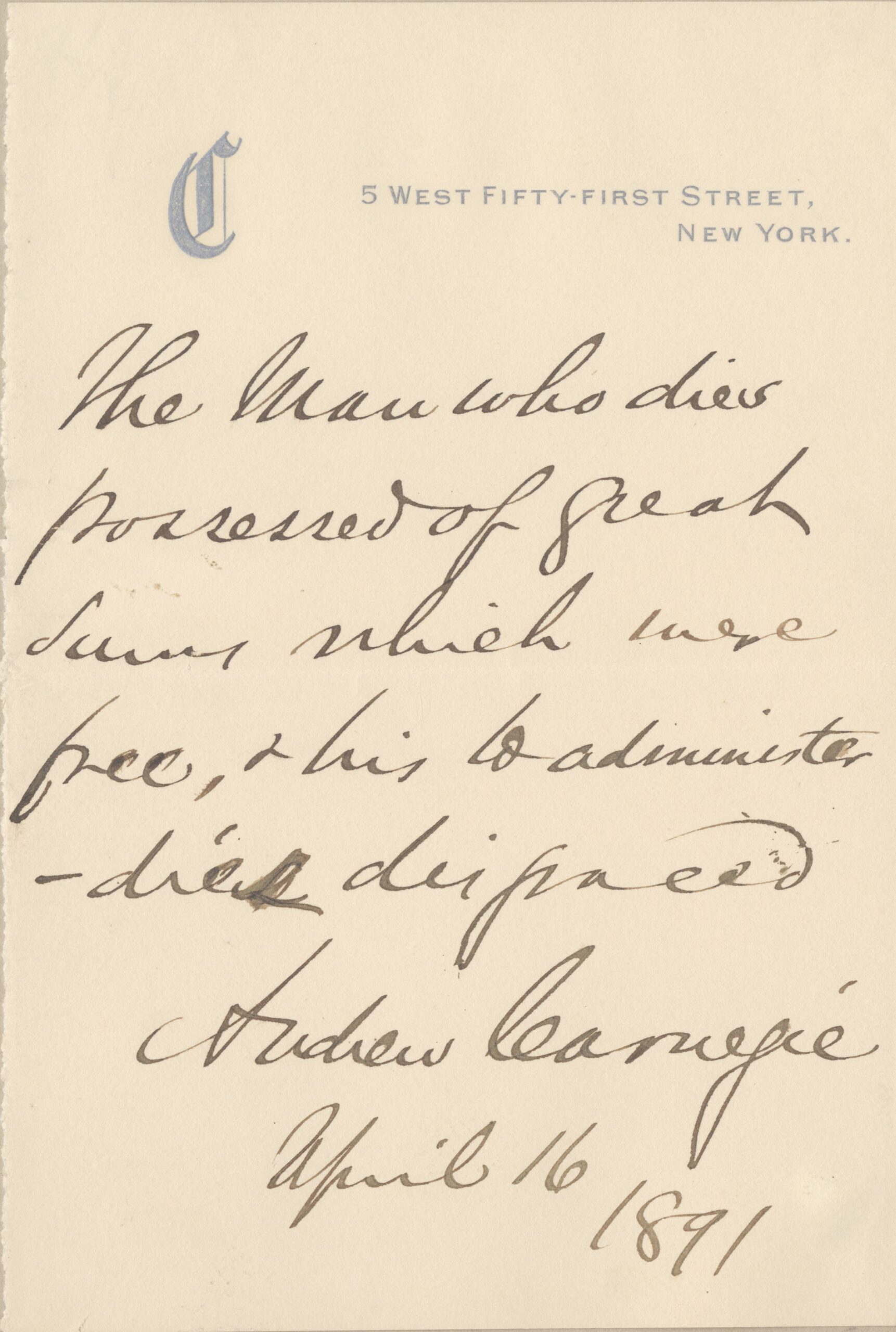

As I contemplated the Centennial year and my role within the Clements, I started to think of the Development and Communications Division as a connector of the past, present, and future—perhaps not unlike Mr. Clements. We have modern tools in social media to help highlight stories in the collections for the public and we seek out gifts that ensure that the Clements Library will be here well into the future. One of Dr. Moniz’s research sources was the Divie and Joanna Bethune Collection (1796–1853), but that isn’t the only place we find philanthropy in the archives.

Benjamin Bussey (1757–1842) was a Revolutionary War veteran, excellent businessman, and philanthropist. The Benjamin Bussey Collection at the Clements holds letters from acquaintances, organizations, and even strangers asking Bussey for loans and charity. He responded positively with gifts to a wide range of organizations.

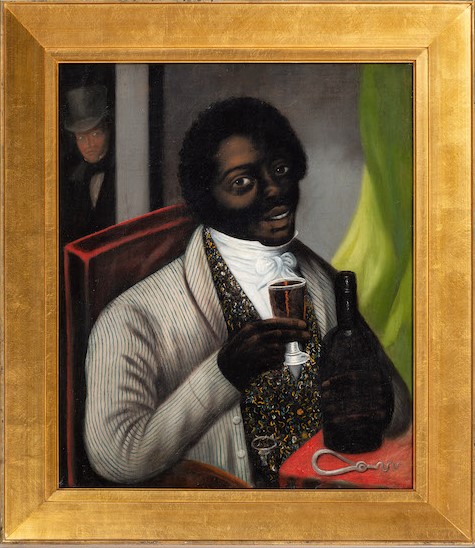

Those seeking to influence public perception have long known that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” and the inexpensive availability of trade cards and photos in the 19th Century helped to make them a viable fundraising tool. We have images of social activists Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) and Sojourner Truth (1799–1883) that were sold to advance their work. Some who purchased these cards admired the activists and their causes enough to display their photos in family albums.

Other fundraisers used images to support the institutions where they worked. For example, we see the emergence of a professional fundraiser in Reverend Henry Leonard, the “financial agent” of Heidelberg College (now Heidelberg University) in Tiffin, Ohio, for thirty-two years. Leonard posed for a series of photographs documenting his “fishing trips” to raise money for the University. He was well-known and beloved for his work and his story lives on in the Maxson Ephemera Collection.

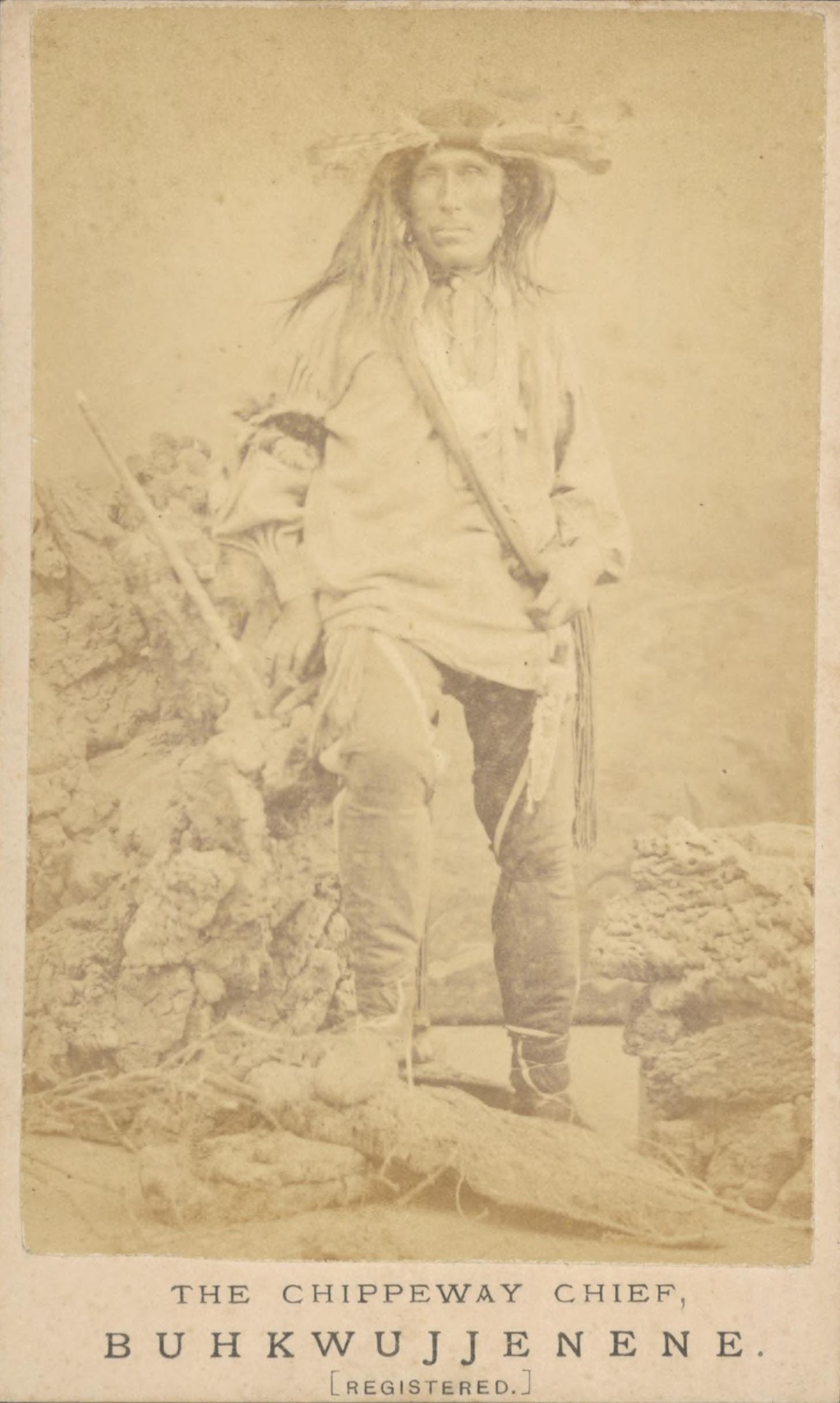

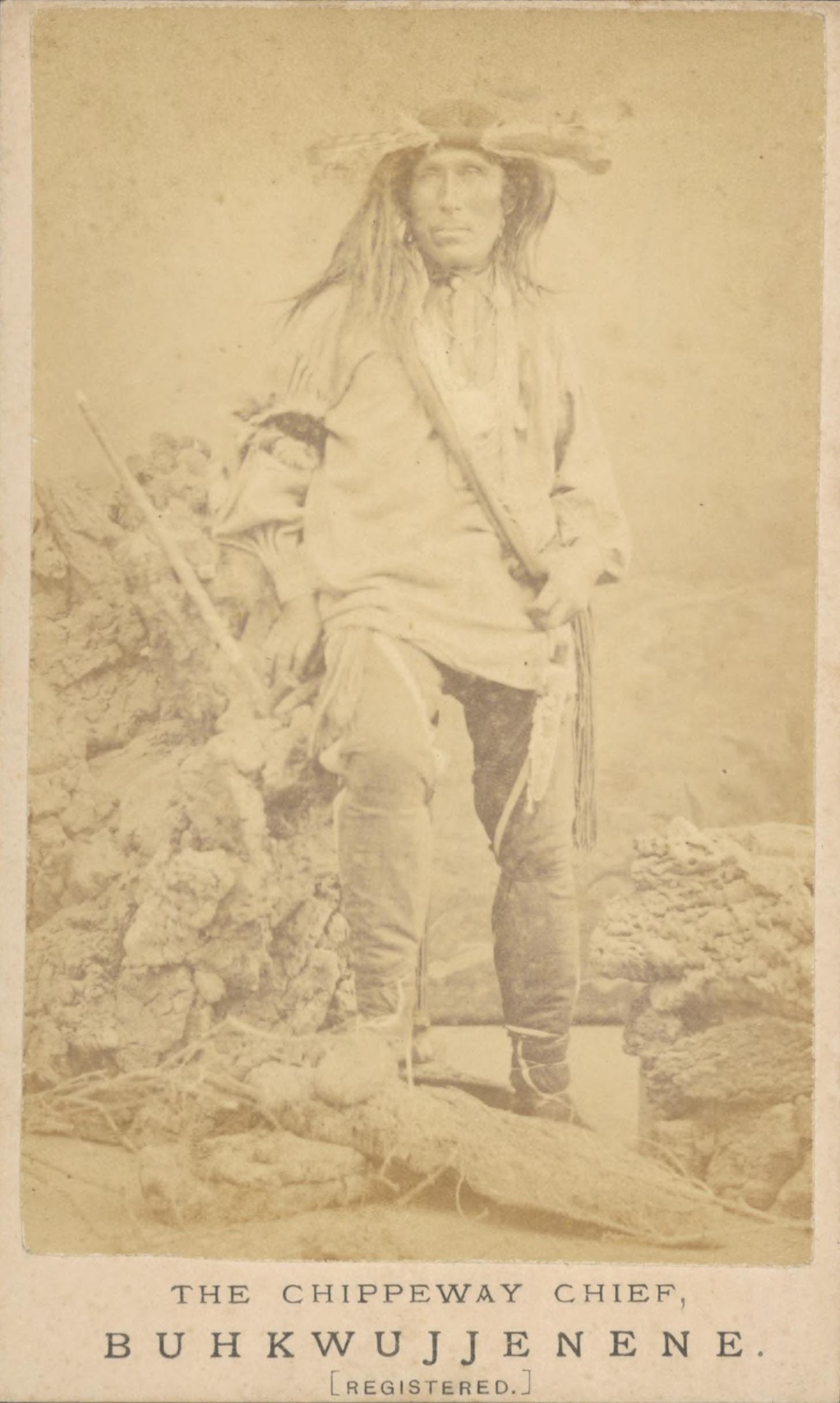

Photograph taken in 1872 during Rev. Edward Francis Wilson (1844–1915) and Ojibway Chief Buhkwujjenene’s visit to England while fundraising for Shingwauk Indian Residential School. Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography. Gift of Tyler J. and Megan L. Duncan.

Henry Leonard re-enacted his “fishing trips” for the camera. Maxson Album #14, gift of Jerry and Charlotte Maxson.

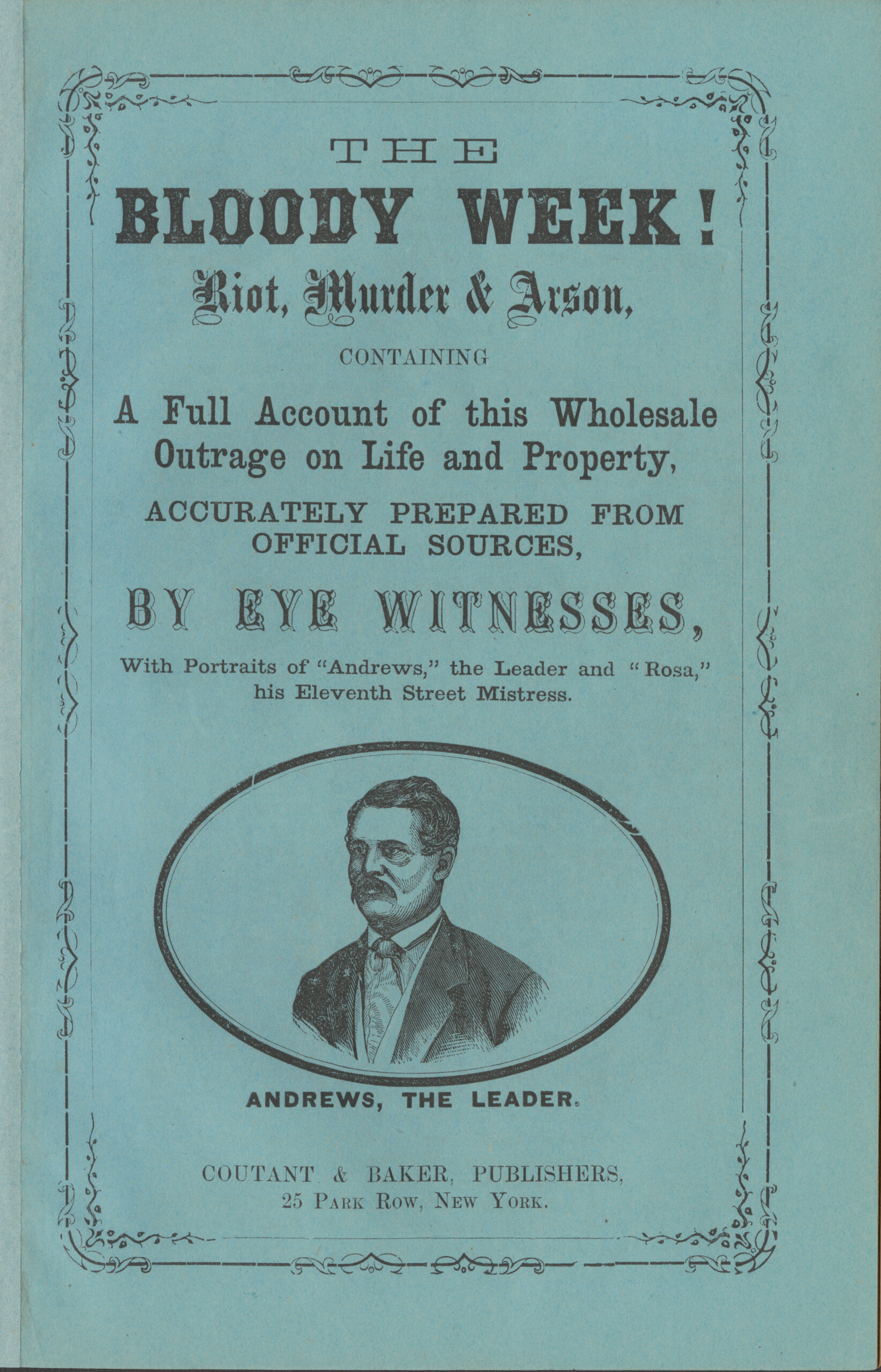

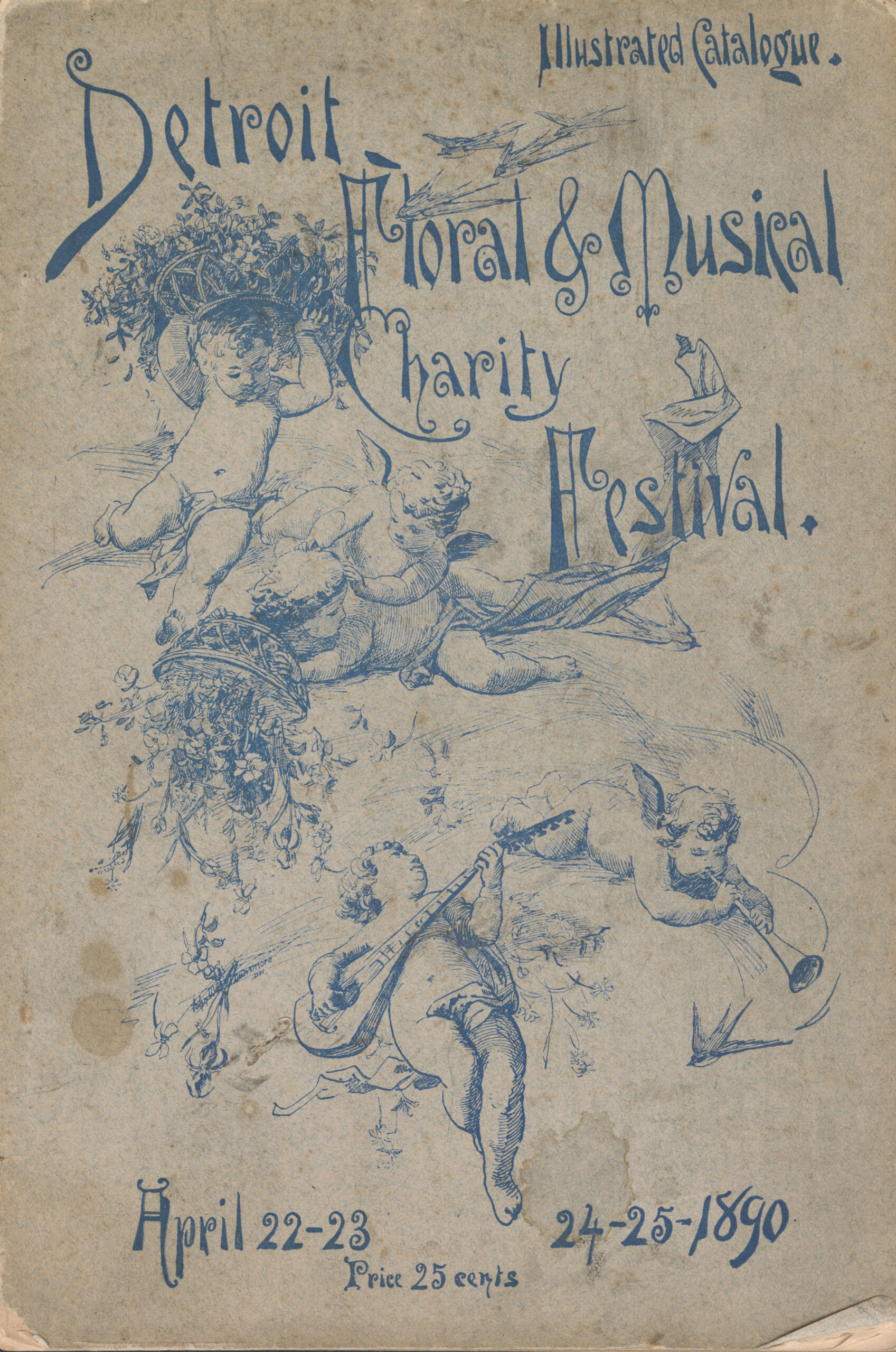

A richly illustrated catalog of the floral and musical festival in Detroit, Michigan, records the efforts of the many volunteers who in 1890 enjoyed the camaraderie of planning a community event to raise funds for many causes around the city. We learn that at the 1889 event, nearly 35,000 people attended, garnering $11,000 that was split among twenty-one charities.

Did you notice that the illustrations provided were also all donations? Philanthropy at the Clements Library has been woven into all we do since the inception of the institution. I hope that I serve this institution in a way that builds our foundation for the next century by valuing your partnership in this endeavor.

— Angela Oonk

Director of Development

Illustrated Catalogue of the Floral and Musical Charity Festival (Detroit, 1890). Gift of Martha Seger.

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

Manuscripts

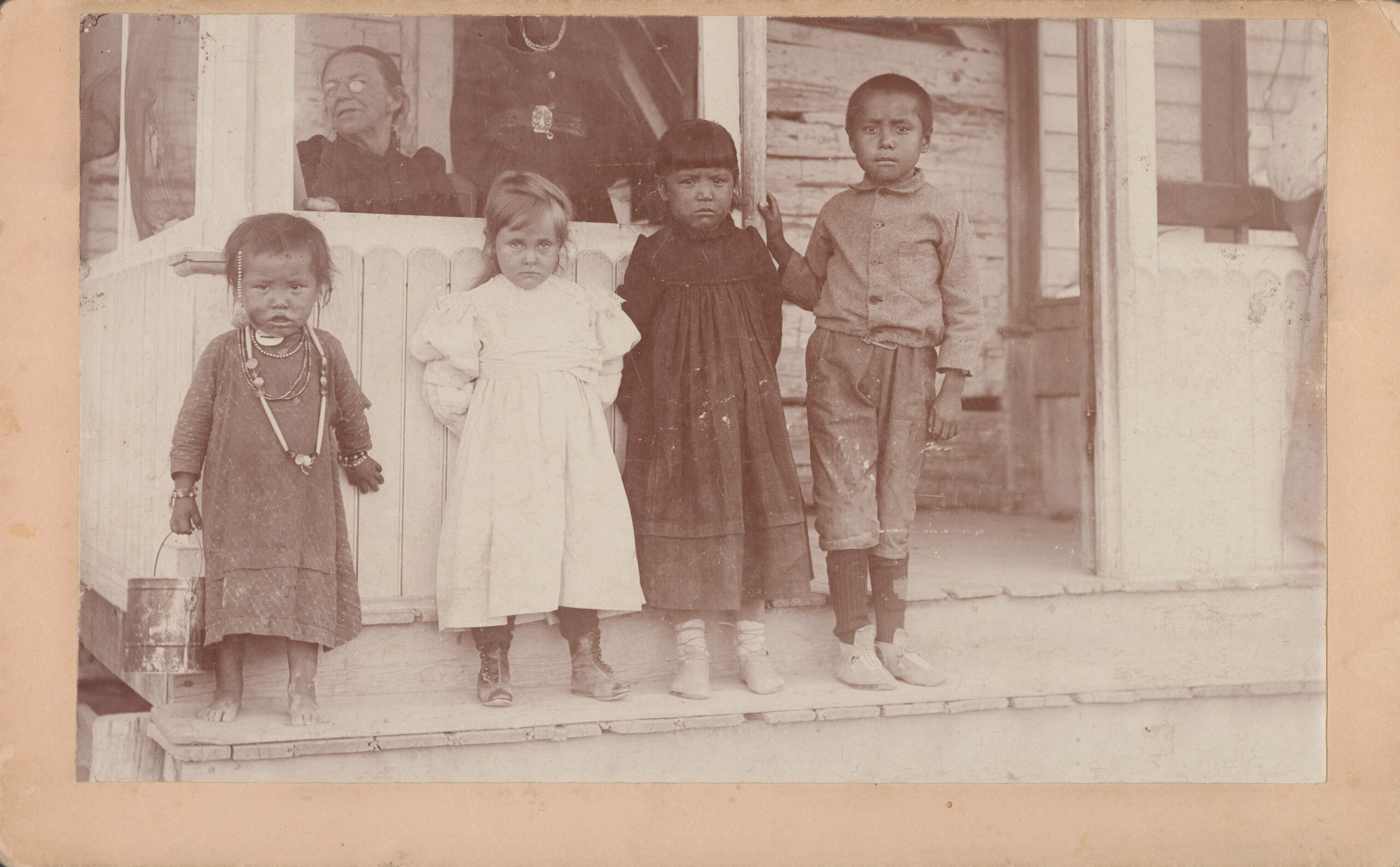

The Clements recently acquired the 19-item Crow Creek Agency Collection, focusing on a Native American boarding school in Crow Creek, South Dakota. Included is a program for the 1892 Christmas celebration, which lists songs and recitations performed by the students, providing a glimpse of student life at this boarding school and how American culture was represented and taught.

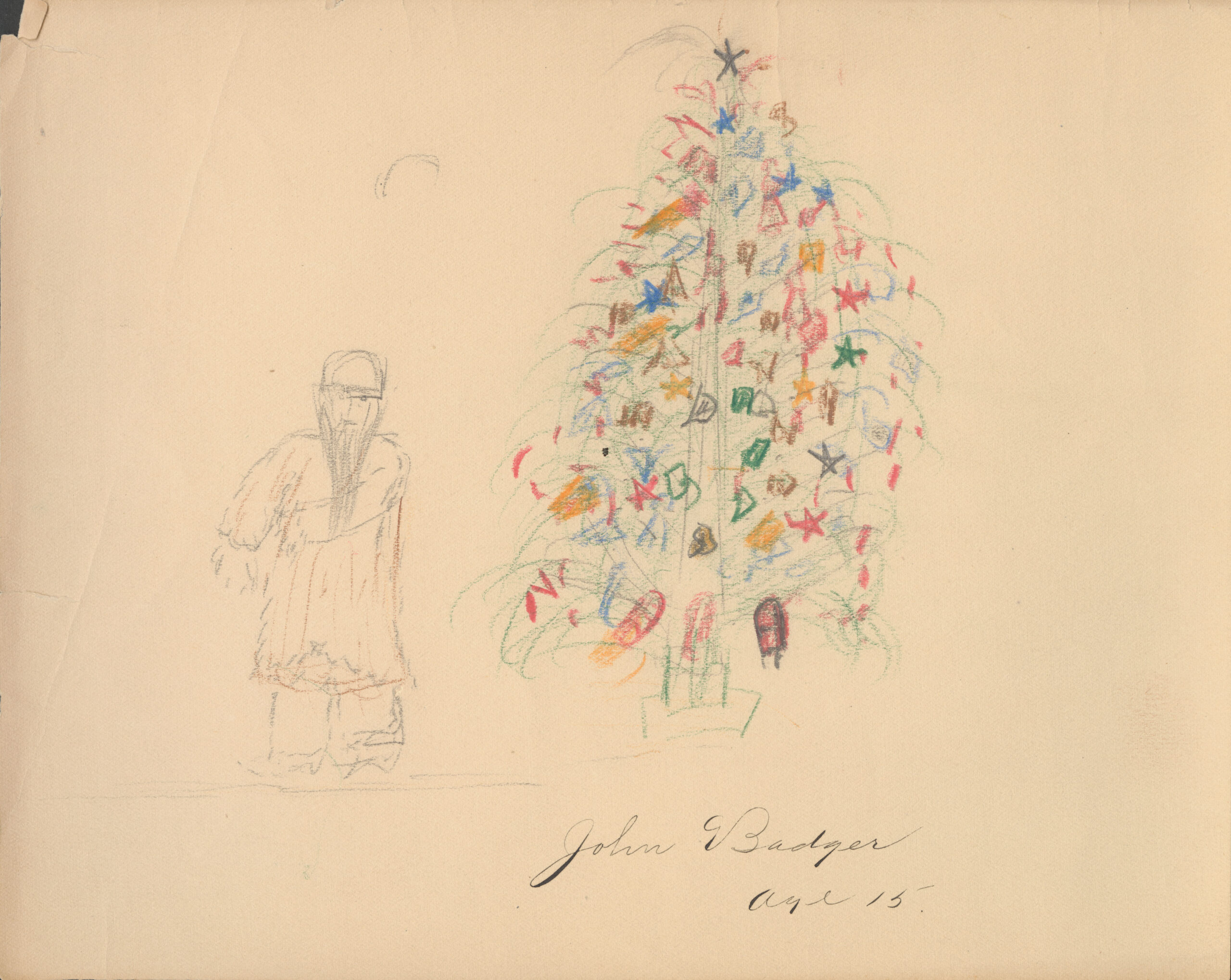

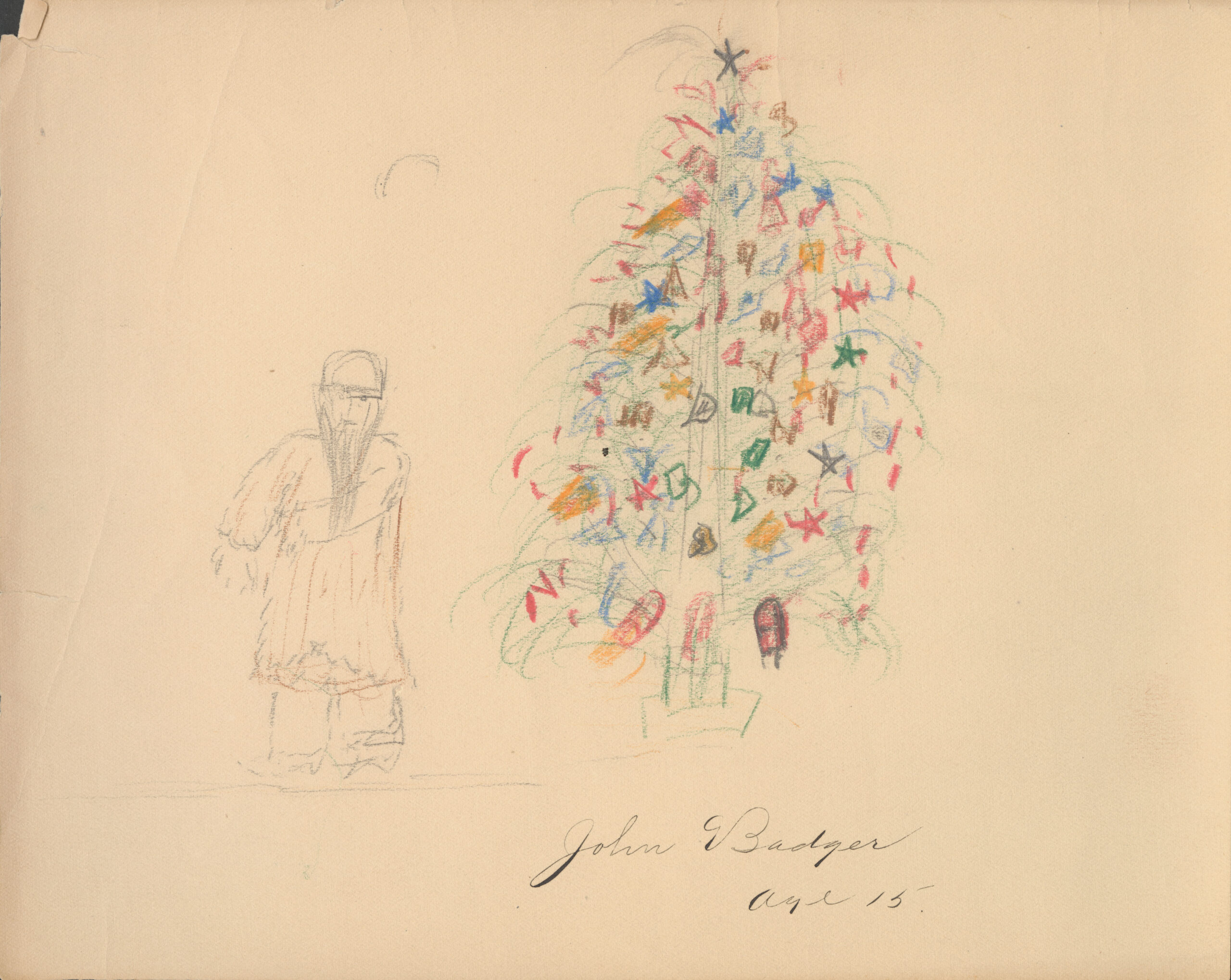

Drawing by Crow Creek boarding school student John Badger, age 15.

Evocative student work accompanies the collection. There are eight letters from students who shared their experiences at the Christmas celebration. Many of them wrote about the presents they received and highlighted the week spent at home with family over the holidays. The collection also includes geometric drawings and collages, examples of how these children expressed themselves in moments of forced cultural assimilation that demonstrate how art can help us think about trauma and its relationship to heritage.

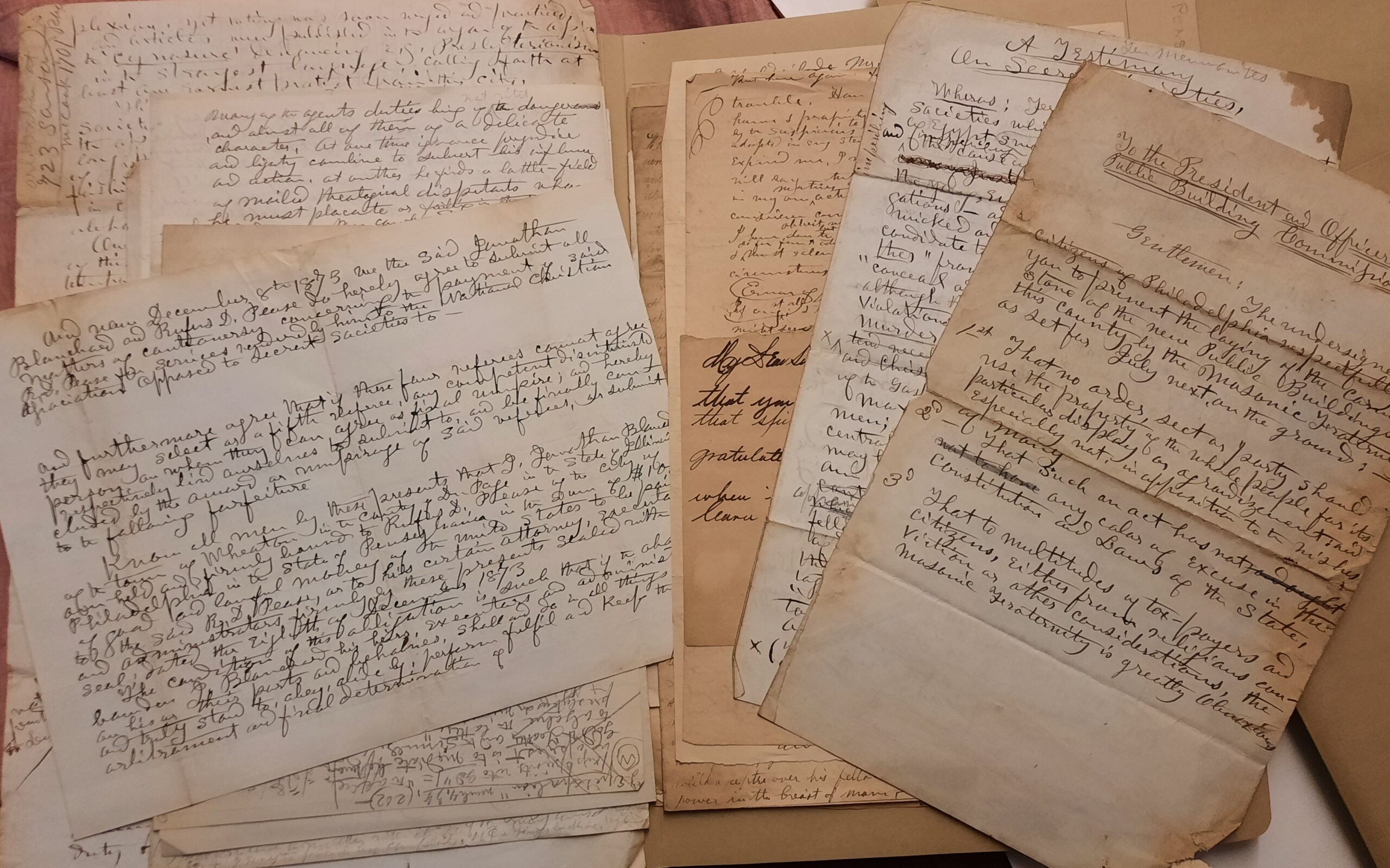

One of the larger recent acquisitions is a collection of papers of Rufus Degranza Pease, including letters, a diary and writings, printed material and more. Pease was a graduate of Willoughby Medical College in 1845, and became an itinerant lecturer on a variety of topics, including astronomy, geology, health, physiognomy, phrenology, and free thought. Following the Civil War, he lectured for the National Association of Christians Opposed to Secret Societies, focusing on Freemasons, Knights Templar, the Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, and others. Later in his life he became a doctor of physiognomy in Philadelphia where he resided until his death in 1890.

A selection of draft documents from the papers of Rufus DeGranza Pease.

Much of the correspondence to Pease is from fellow peddlers of educational services and instructive lectures in the Midwest. They collaborated and traded information and advice on travel routes, discussed which communities were receptive to their services, and how much could be charged for lectures and classes.

Other letters written by Pease are filled with fury, directed toward Mormons among others. Pease was an abolitionist and anti-slavery advocate, though he raged at Lincoln for the suspension of habeas corpus in 1863. He also believed that he was being persecuted, seemingly somewhat justified by his imprisonments for “seduction and fornication.” He wrote during one imprisonment in October/ November, 1863: “For my part I have seen the hand of Providence in the matter from the first, and cannot doubt that I am bruised for the benefit of your community. No silly and contemptible malicious charge against me of insanity, even though bolstered up by sap headed drug and quack medicine peddlers of Berlin [Wisconsin] as elsewhere, will avail against the true and right…The charges they had diligently circulated for months about me were fornication, even going so far as to specify a person, and also seduction. But finding they could make no headway in that direction immediately commenced to cuttlefish under a wholesale and cold-blooded charge against me, even to indict me of partial, if not entire insanity.”

During his later years in Philadelphia, Pease earned money by providing phrenological and physiognomical advice. He conducted a mail order business, soliciting letters from clients, which arrived with enclosed photographs, posing questions such as: Will I be a good candidate for the priesthood? What type of career should I pursue? For the exorbitant fee of $10, Pease would provide answers by return mail, presumably based on physical characteristics exhibited in the photographs.

Printed materials include the only issue that Pease ever produced of the Journal of Man, published by Rentoul in Philadelphia in 1872, as well as a variety of lecture and course advertisements, synopses and tickets, flyers, and circulars.

Books

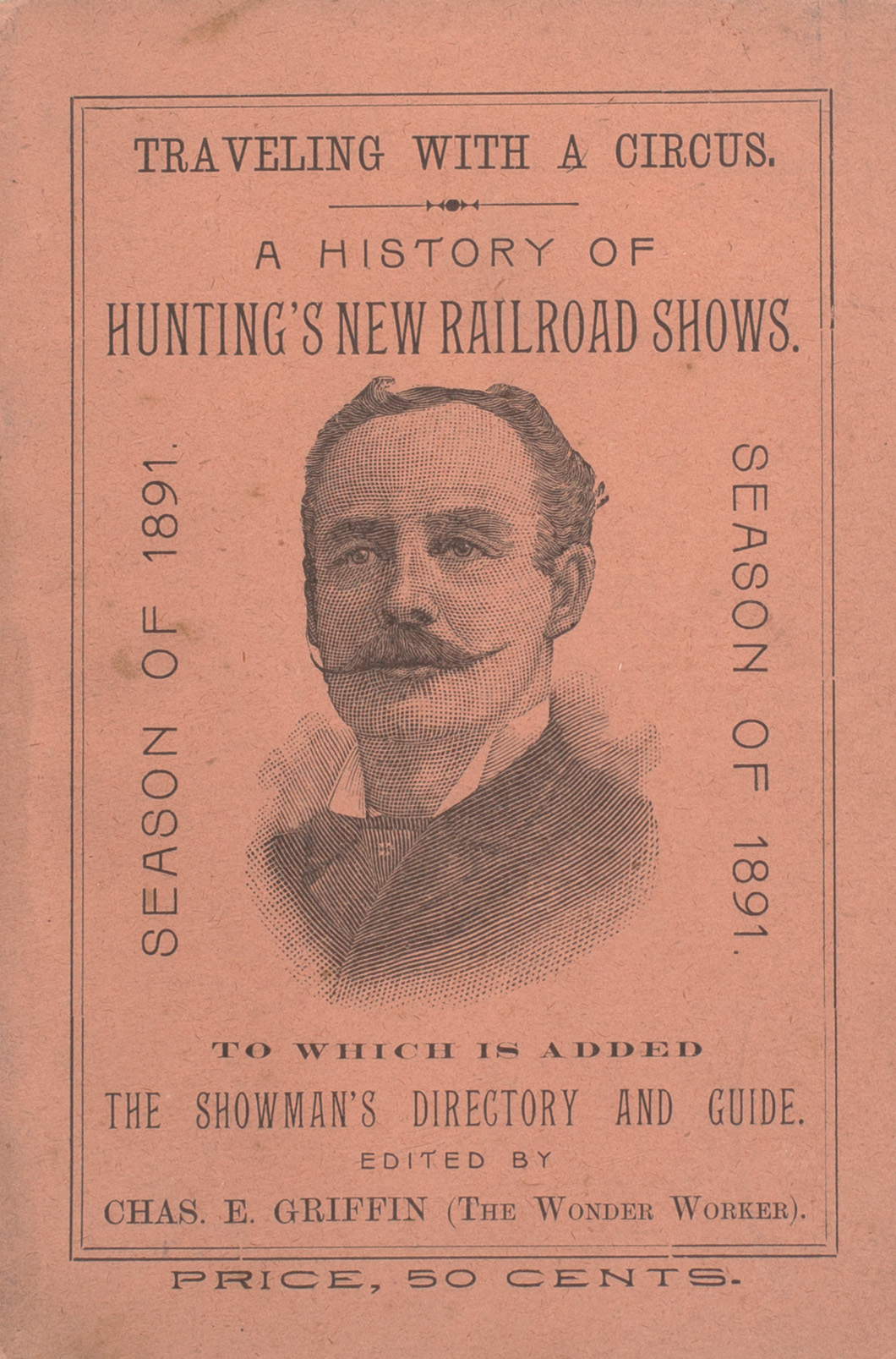

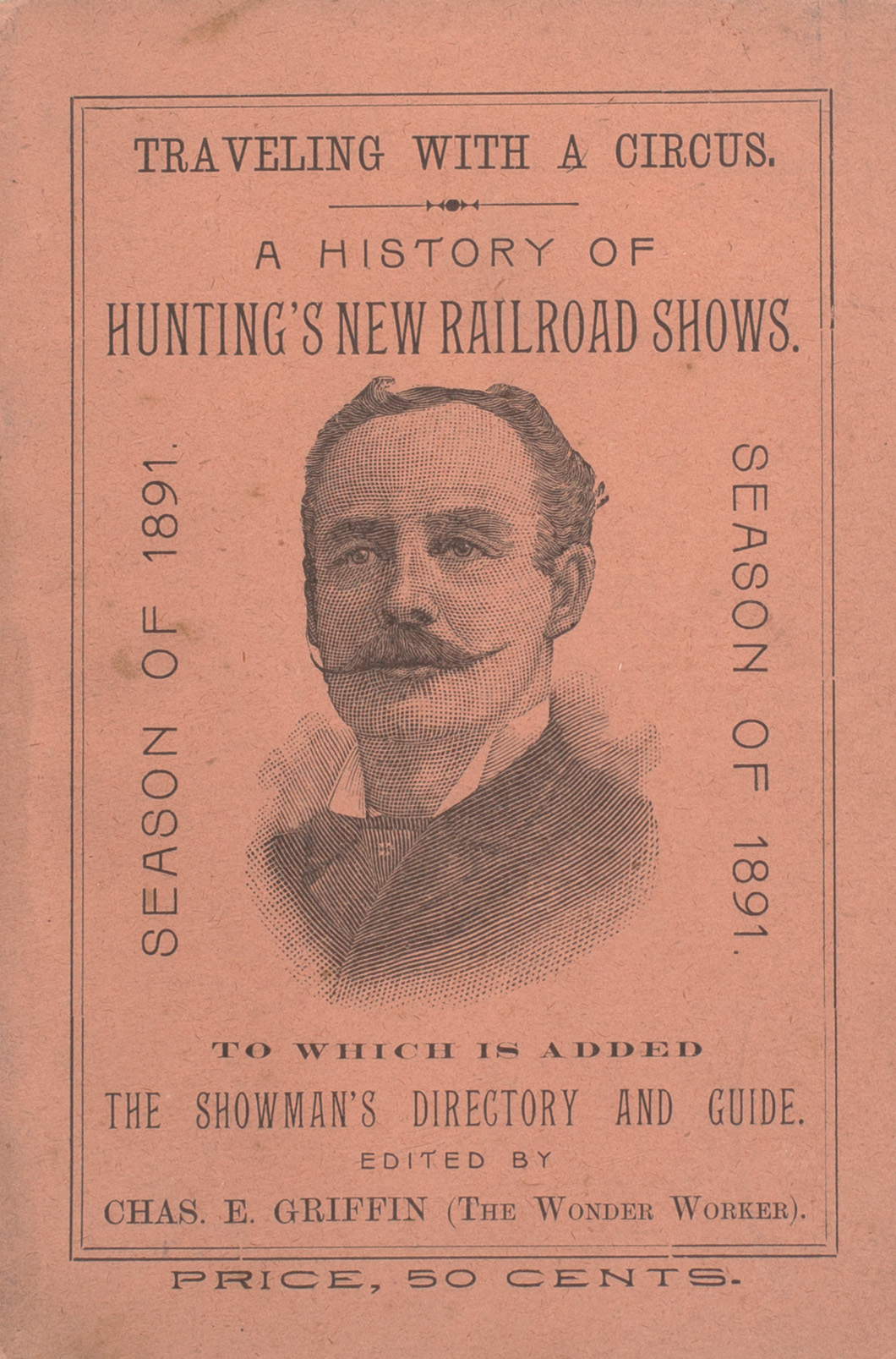

The route book for 1891 features a cover portrait assumed to be Robert Hunting (ca. 1842–1902), “Sole Proprietor and Manager” of Hunting’s New Railroad Shows.

New to the Book Division are three pamphlets related to Hunting’s New Railroad Shows, or Hunting’s New United Monster Railroad Shows, a circus traveling by rail car to locations around the United States. The pamphlets are referred to as route books and contain accounts of the seasons of 1891, 1892, and 1894. Each route book starts out with a list of the performers and support staff who traveled with the circus, including: cooks; musicians and other performers; an advance team that traveled ahead to take care of the advertising and to set up the tents; and caretakers for the animals, among others. The heart of each pamphlet is the “Author’s Diary,” comprised of snapshots of stops on the season’s itinerary, recording the location, the population of the towns, the railroads taken to get there, the weather, and any notable events. The financial success of the show is often noted—“bad business,” “fair business,” “good business,” or “big business” (the maligned Easton, Pa. keeps up its reputation of being a “‘bum show town”). The entries provided vivid accounts of the challenges of managing a traveling circus—wrangling people, equipment and animals; the sometimes gruesome injuries sustained by performers; railroad mishaps; and the revolving-door entrance and exodus of performers along the way.

An example from 1892:

Brewsters, N.Y., May 31.— First real

“circus day” of the season. During

the parade this morning a wild bull

made his appearance and stampeded our lady and gentlemen

riders. Prof. Mohn led the enraged

beast a wild chase down a narrow

alley, and Jeanne Earle created a

sensation by making a daring leap

for life from the back of her fiery

steed to terra firma. Where the beast

came from or where he went is an

unsolved mystery. This is the home

of a great many retired showmen.

Mr. Henry Barnum, who is now

connected with the Forepaugh

Show; Mlle. De Granville (Mrs. Dr.

Knox) and Lew Baker, an old time

boss canvas-man, were visitors.”

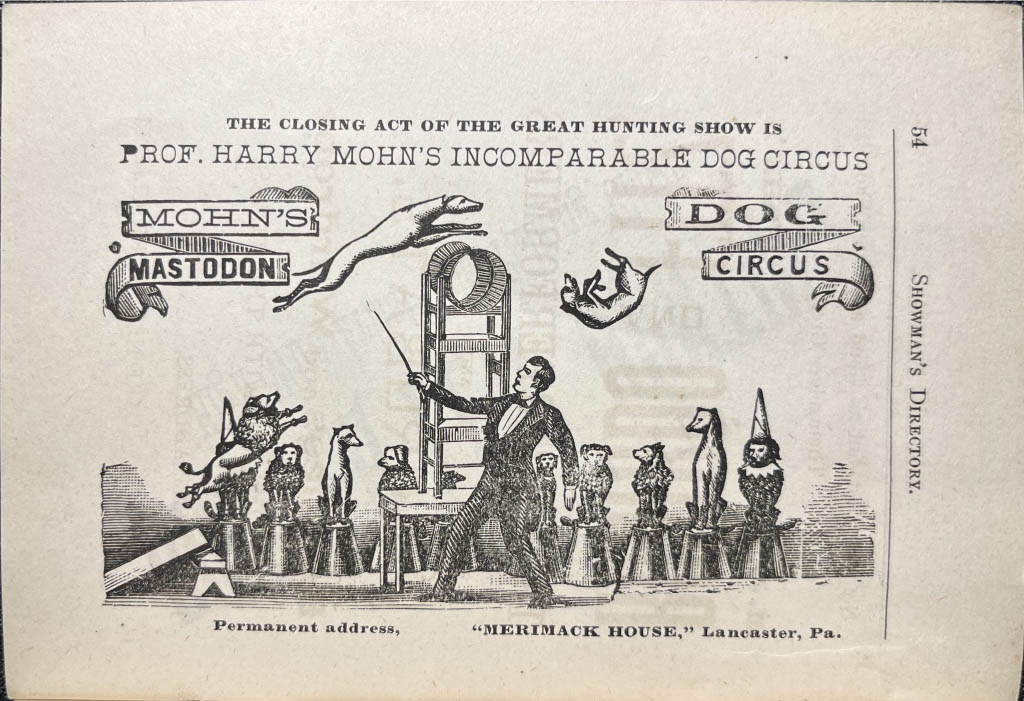

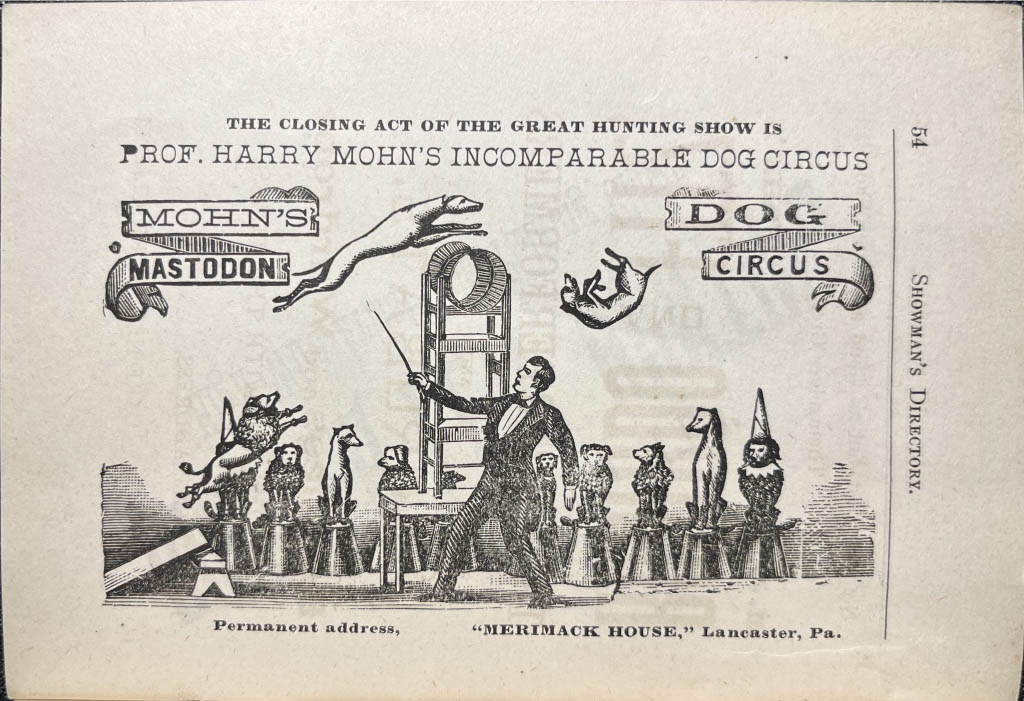

One of the acts advertised in the 1891 guide was “Professor” Harry Mohn’s dog circus. Mohn was featured in an entry describing an eventful stop in Pennsylvania: “A Duncannon loafer stole one of Prof. Mohn’s trick dogs after the night show, but Harry succeeded in getting the dog back before he left town. Harry Smith was kicked in the groin by a tough. It will lay him off for several days.”

Two of the pamphlets include a “Showman’s Directory and Guide,” compiled annually. The Directory listed contact information for performers and service providers who might be needed by a traveling show. If you required new balloons, or ran out of circus lights, or were in need of canvas, magic lanterns, or a taxidermist, contact information is available! There are listings for engravers, lithographers, printers, tightrope walkers, clowns, jugglers, and musicians—the panoply of services required to keep the show on the road. The collection reveals the cooperation that existed among similar outfits, who traded information and provided mutual support.

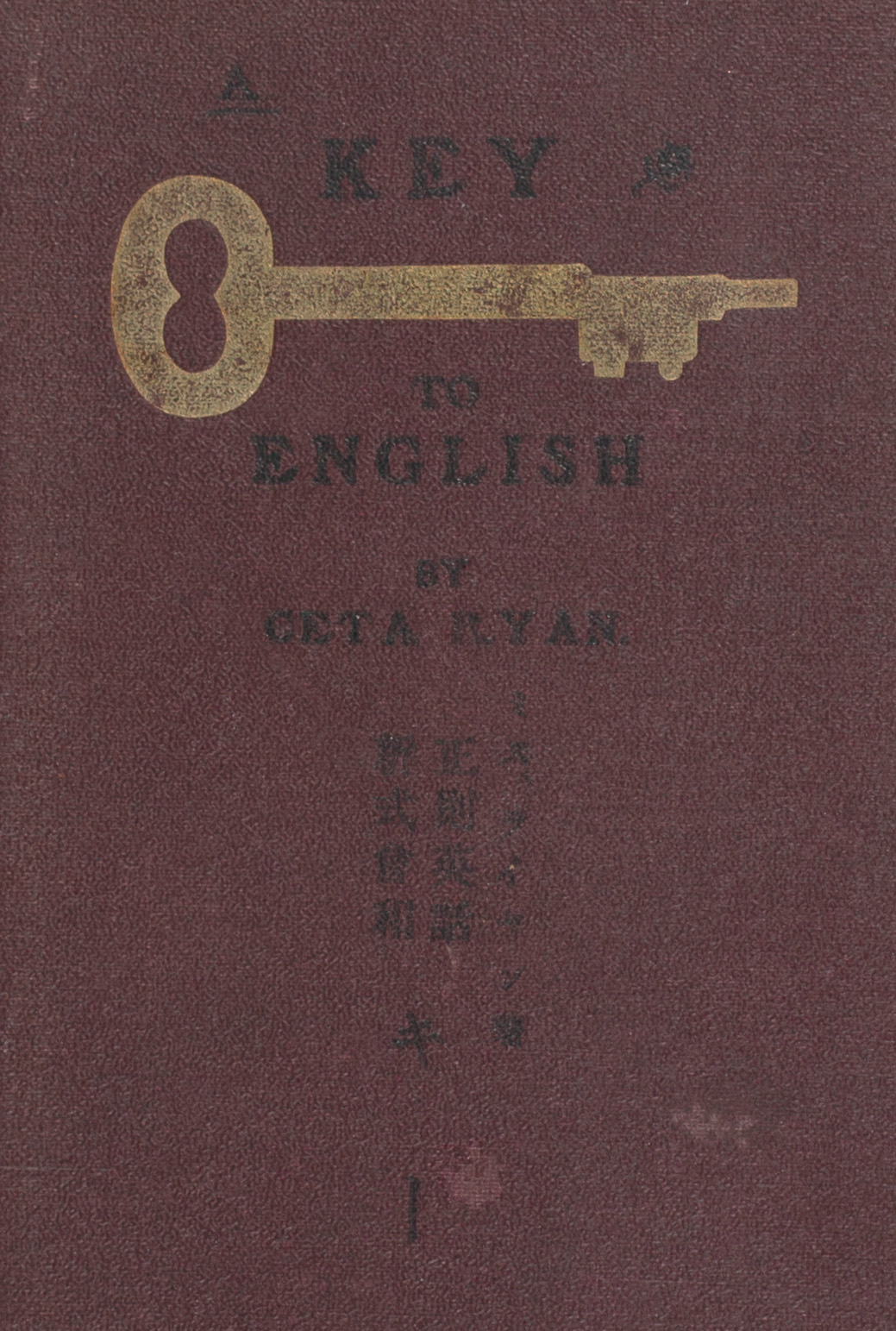

Also recently acquired, A Key to English is a textbook produced by Ceta Ryan to help Japanese immigrants in California learn English. An imprint from 1906 San Francisco is a rarity in itself, given the earthquake and subsequent fire which burned much of the city. But the volume is interesting in several other aspects. The text is printed in both English and Japanese, which was a complicated task for the printing technology of the era. Information inside the back cover indicates that this book was owned by someone who spent time in the internment camp in Poston, Arizona, during World War II, revealing that it had a fairly long life in readers’ hands and somehow wound up in a carceral setting.

Little is known of the author of A Key to English. Census records list a woman named Ceta Ryan (born ca. 1865), a private teacher residing in San Francisco as late as 1940 along with a lodger born in Japan. We have no information about the owners of the volume, or who penciled the inscription on the inside back cover.

Books

Recently arrived in the Graphics Division’s growing collection of ephemera, is a fascinating tiny redware souvenir—measuring 3.5 cm—made to look like a soldier’s canteen and to commemorate the Battle of Gettysburg. On one side is affixed a photograph of a woman named Jenny Wade, who lived in Gettysburg with her mother and was killed during the battle on July 2, 1863. Wade and her mother lived in the middle of the town of Gettysburg, and when the fighting started, moved to the home of a relative. One morning while Wade was kneading dough to make bread for Union soldiers, a Confederate unit began firing at the house. A musket ball passed through the door and killed her. Famously, the day after her daughter died, her mother finished baking the bread that her daughter had started when she was shot and killed, and gave it to the Union soldiers to feed them.

And on the other side of the souvenir is a picture of a man named John Burns, another famous civilian folk hero of Gettysburg. While Burns was almost 70 when the battle began, he was eager to fight with the Union soldiers whom he admired. Burns left his house with an old musket, a top hat, and frock coat and joined in with a Union regiment marching by. He borrowed a rifle from a wounded soldier and fought throughout the Battle of Gettysburg with several different units. Burns was wounded several times, and he achieved fame as a volunteer civilian who pitched in to help the Union cause.

The large amount of iron oxide present in the clay used for redware gives the unglazed earthenware its striking color.

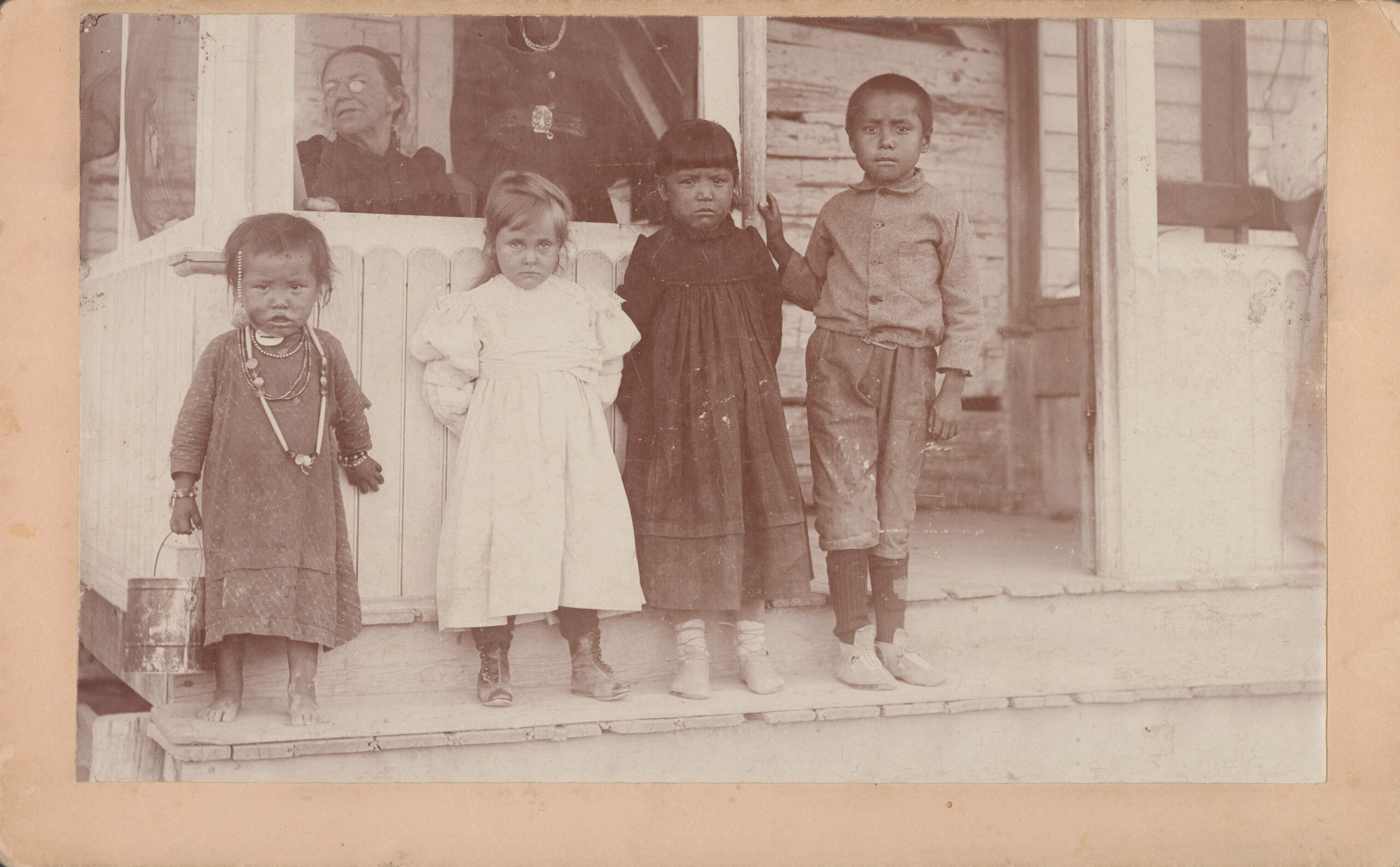

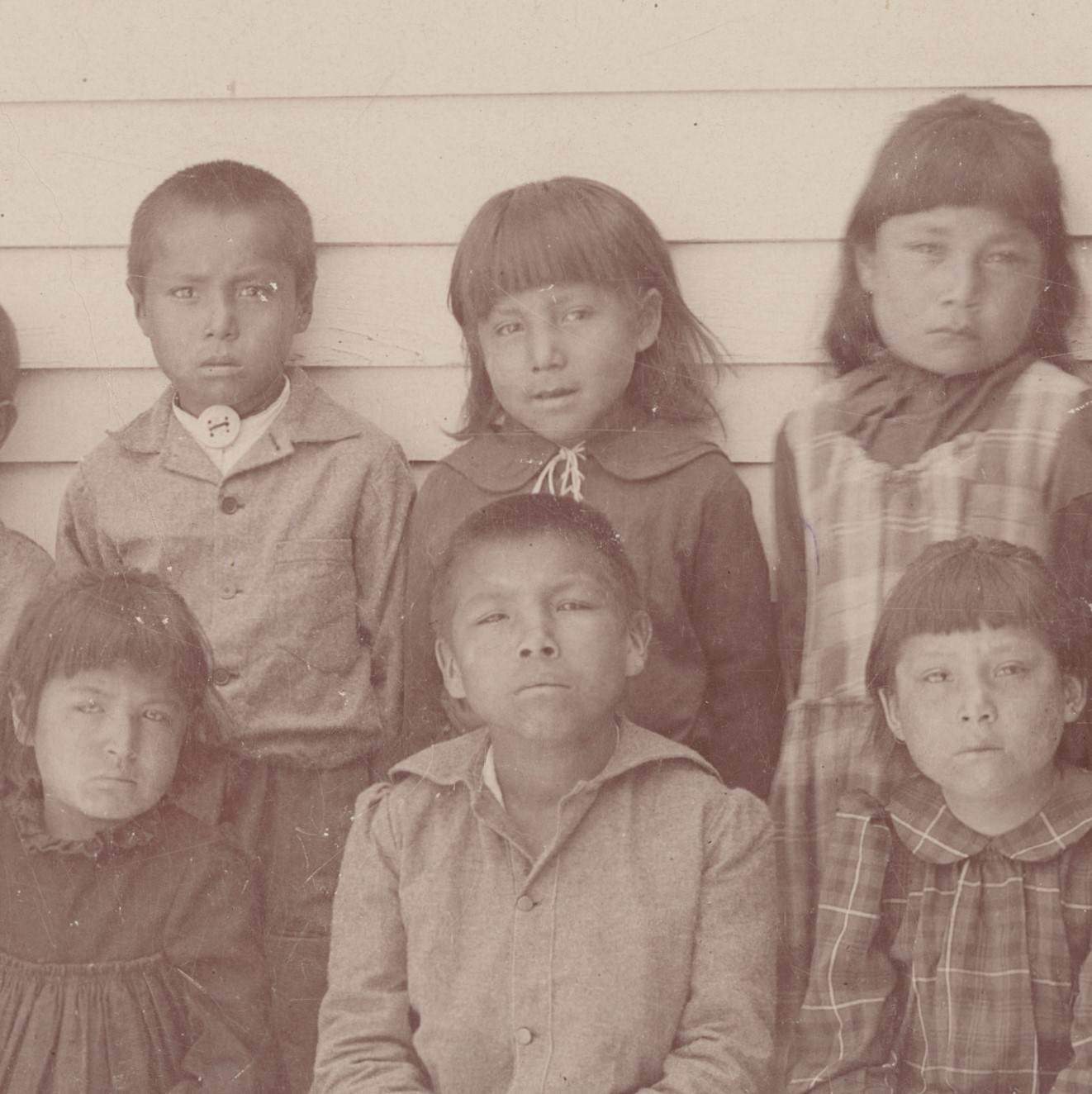

Next is a group of five photographs from the Montana Industrial School for Indians, a boarding school in west central Montana, about an hour or so west of Billings. Unitarian Universalists opened the school in 1886, and it operated for a decade before the federal government discontinued funding and it was forced to close. These evocative images are of the students, who were mostly Crow Indians.

Looking closely at details of these photos, one can spend time noticing the children’s expressions and reflecting on their experiences.

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

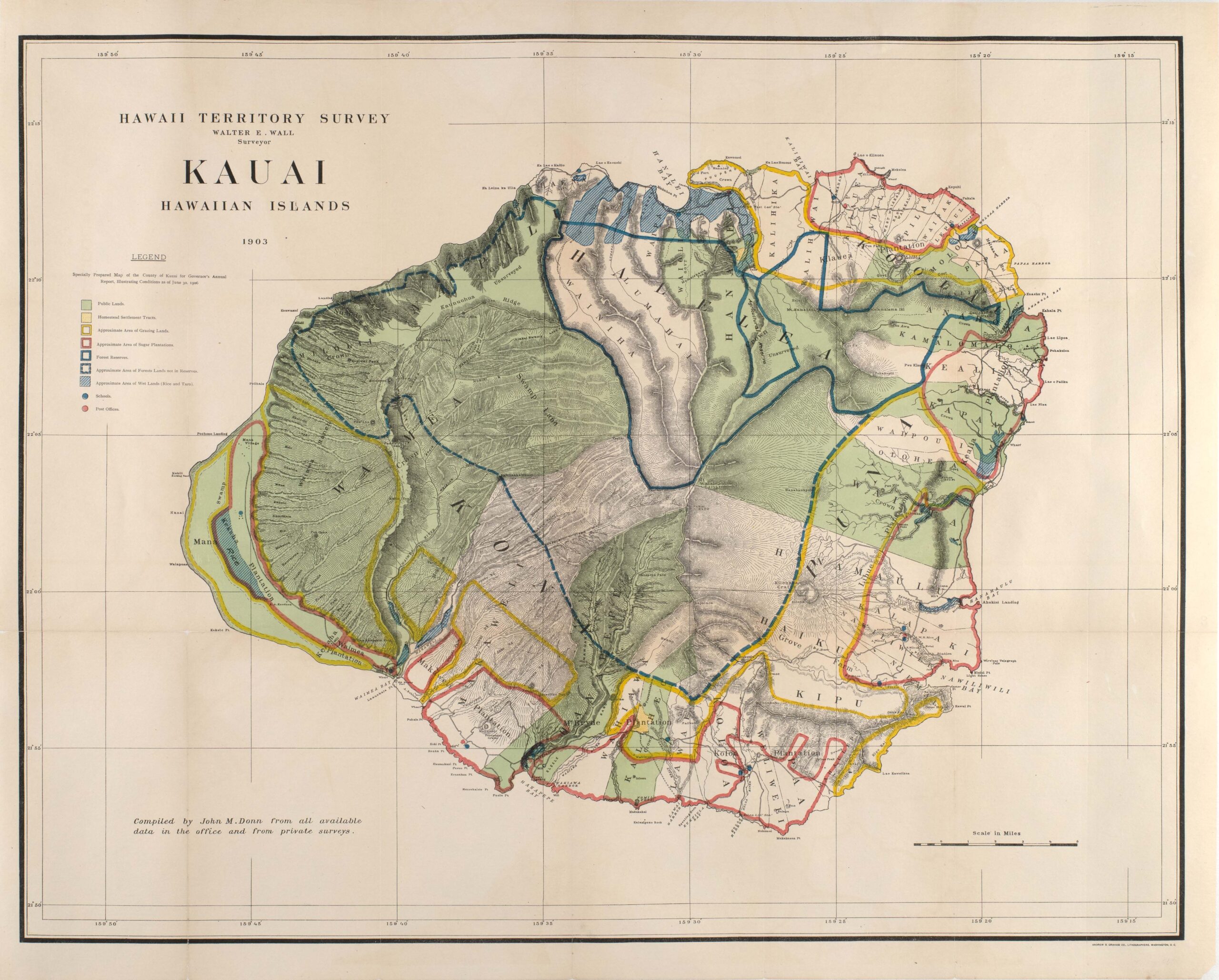

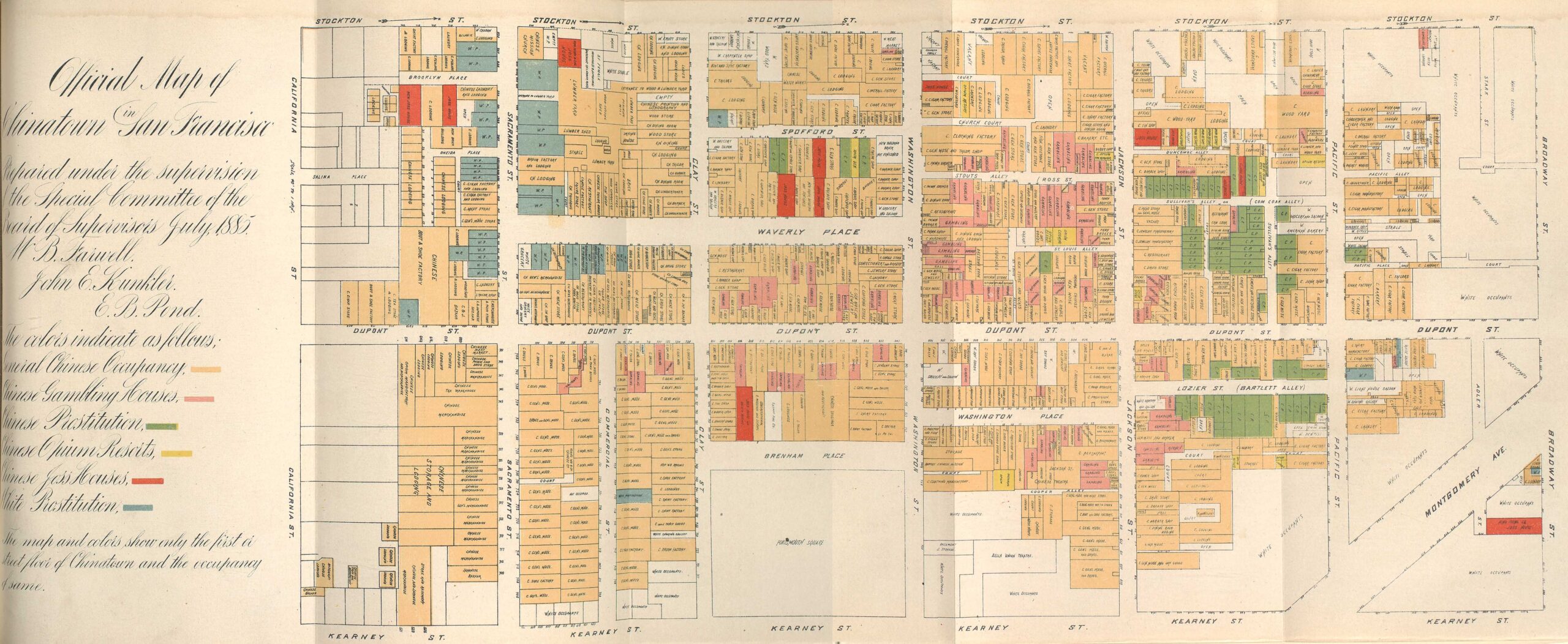

Maps have always been an integral part of the library’s collections, starting with Mr. Clements’ early acquisitions prior to his gift to the University. Because maps reflect time, place, and author’s intent, some research themes can prove more elusive for older maps—for instance, the representation of two important communities on maps: Native Americans and enslaved Africans. While Native Americans held priority of geographic place and African Americans arrived via forced immigration, both groups endured forms of displacement within the North American space.

Detail from Guillaume Delisle (1675–1726), Carte du Canada (Paris, 1703). Delisle, a geographer in Paris, compiled this map from many missionary reports and other first hand accounts from the region, populating the area around the Great Lakes with Native American place names and identifiable groups.

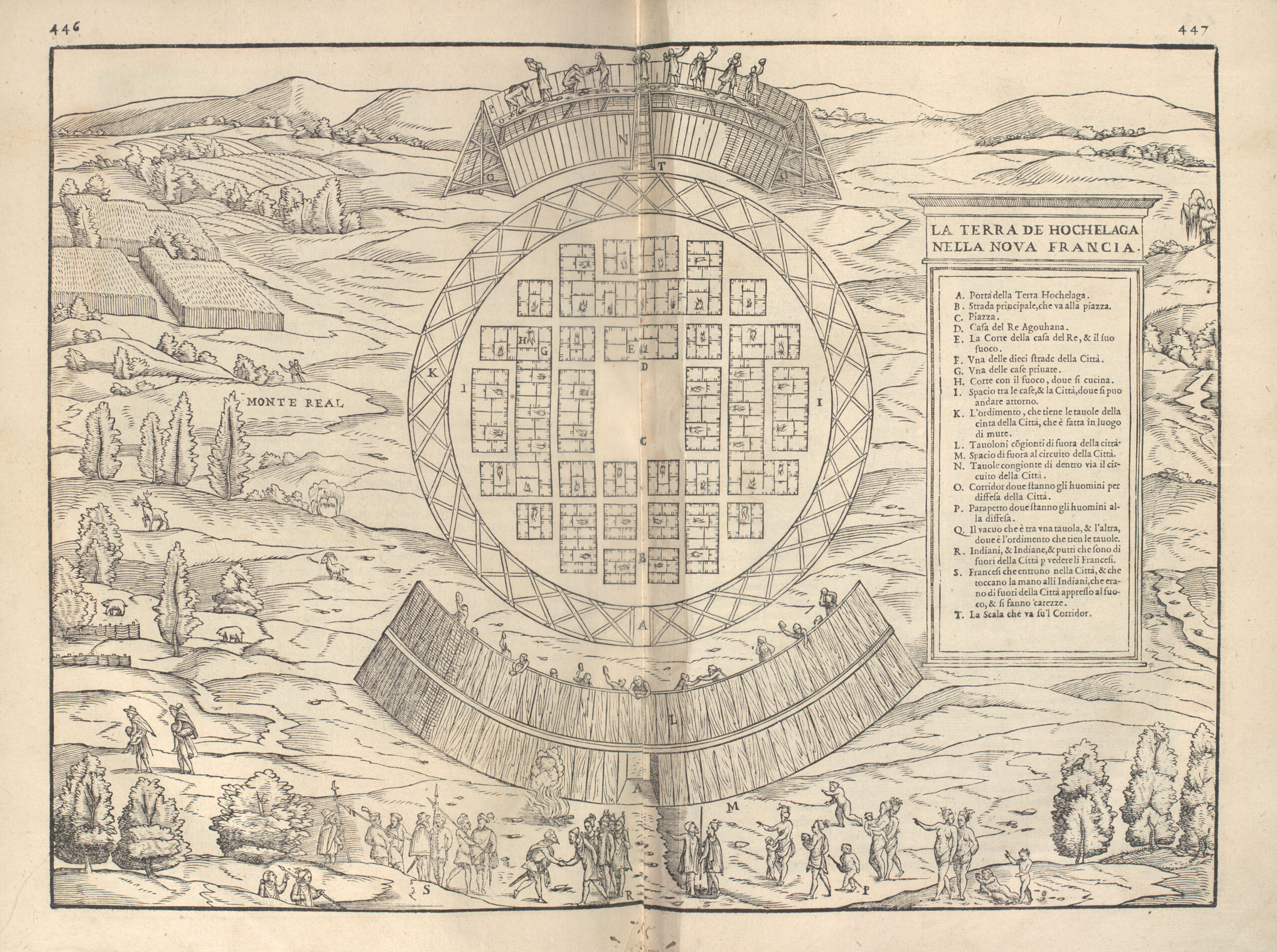

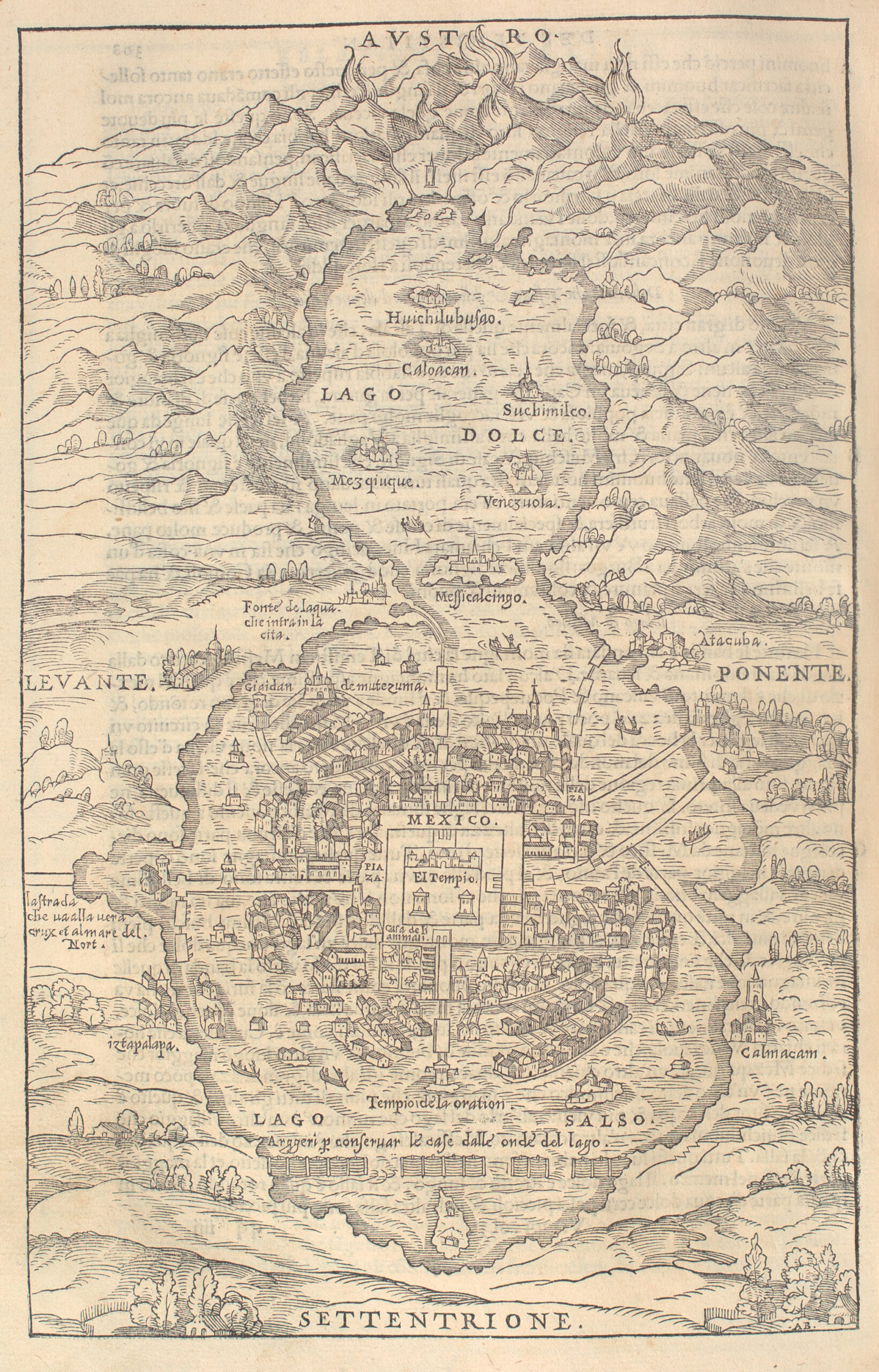

The location of Native American groups in North America challenged mapmakers, given the seasonal mobility and fluctuating numbers of many indigenous groups. Yet their very mobility meant that indigenous modes of mapmaking and representation had much to offer early French explorers and missionaries, who often recorded these verbal and sometimes performative maps, although physical maps were rarely replicated. Nonetheless indigenous presence, indicated by the appearance of various group names, are a staple feature of French maps of North America from the 17th century onwards.

Some British mapmakers who carried out ground surveys in colonial regions similarly included Native American groups, territories, and aboriginal claims. A focused British interest in the location of Native American groups is displayed in this manuscript map. “A Map of the Indian Nations” was probably prepared for the British military administration at the time of the cession of the transAppalachian territory to the British from the French at the end of the Seven Years’ War, more easily visible in a detail of the area around Fort Loudon.

Willem De Brahm, 1717-ca. 1799], “A Map of the Indian Nations in the Southern Department,” 1766.

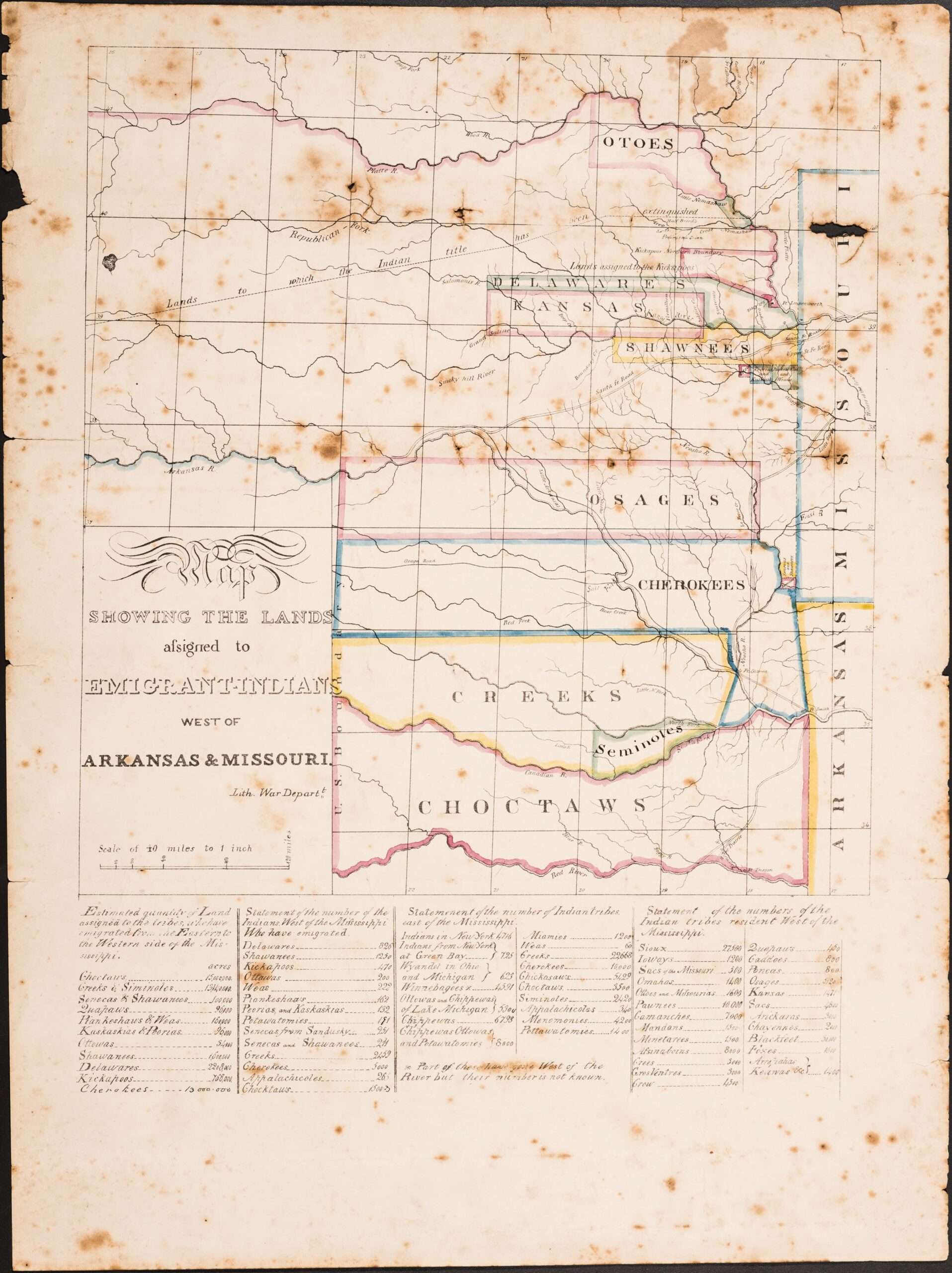

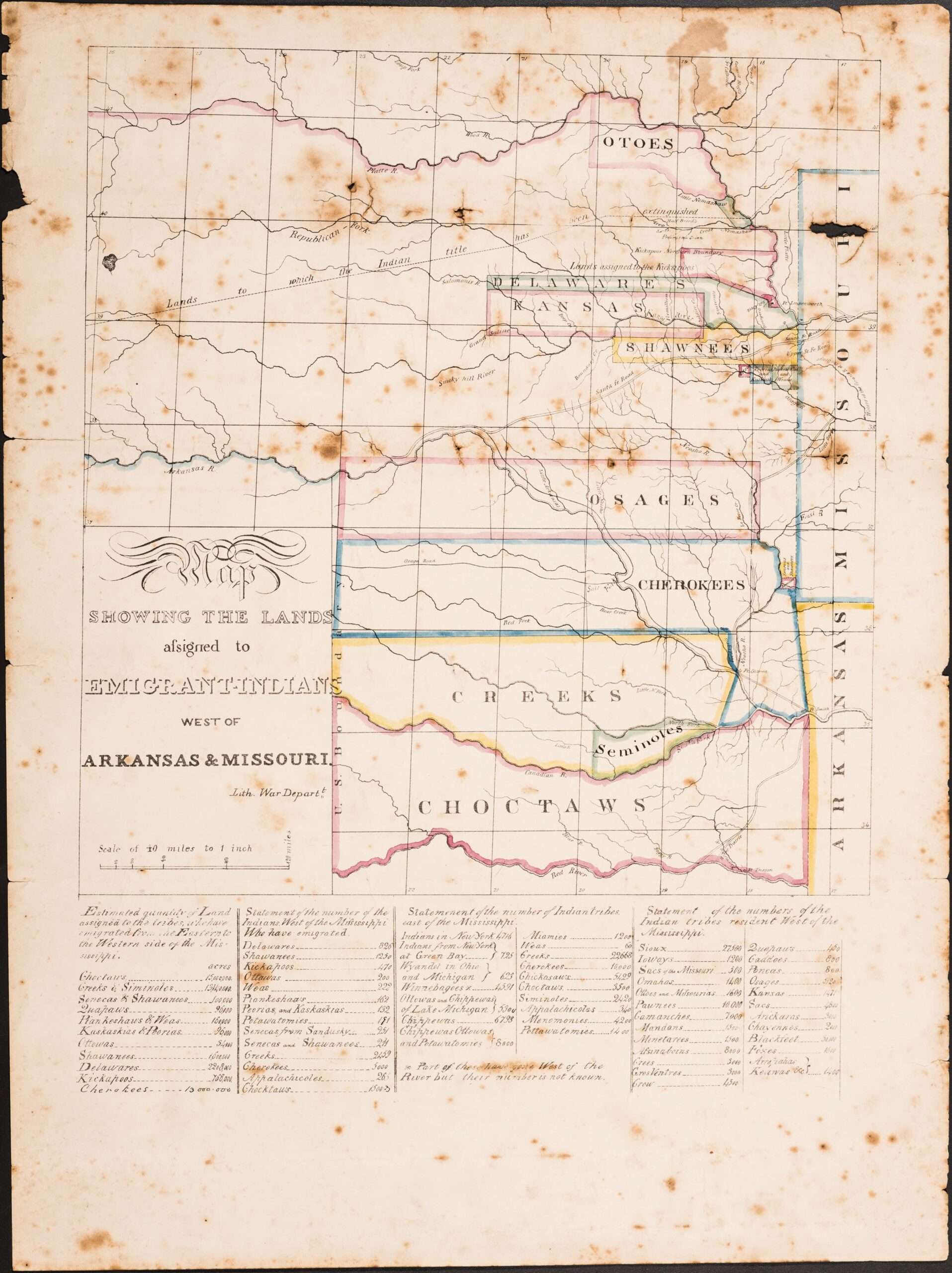

Such maps emphasized the indigenous American presence in regions where European settlers were expand – ing their own footprint. Farmers and settlers of European descent pushed into these western lands between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, with tragic results for Native Americans. Soon designated as “emigrant Indians” the several groups who spread out in the Southern territory on the De Brahm map were squeezed into a much smaller area in what is now eastern Oklahoma, as shown on the War Department map of 1836 (next page). Colored lines indicated boundaries of lands of 10 displaced Native American groups in the wake of the Indian Removal Act (1830), which authorized the federal government to extinguish all Indian title to the lands in the deep South, and 60,000 souls set out on the Emigrants Walk (or Trail of Tears).

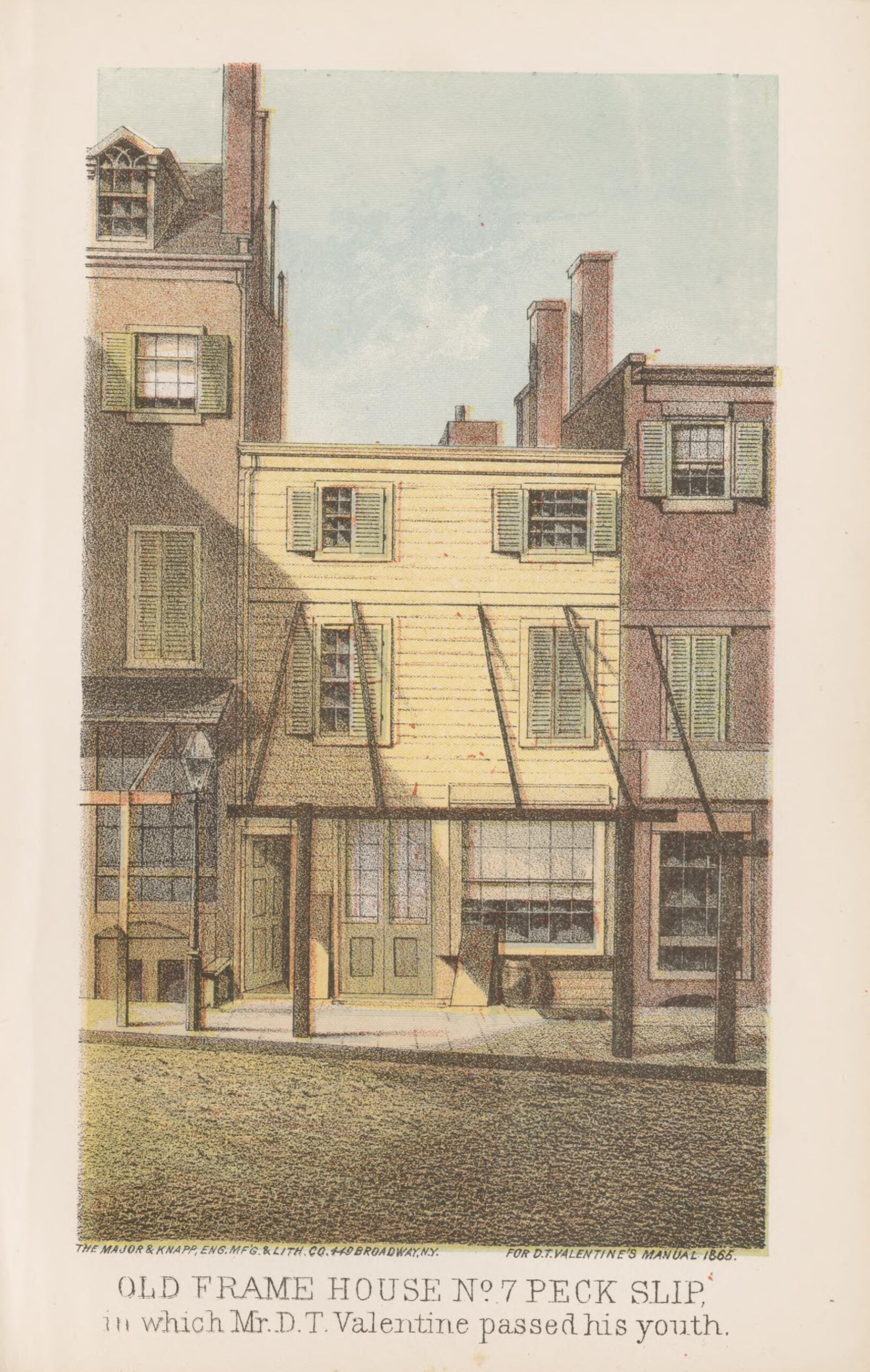

Map Showing the Lands Assigned to Emigrant Indians West of Arkansas & Missouri, produced by the United States War Department ([Washington, D.C.], 1836).

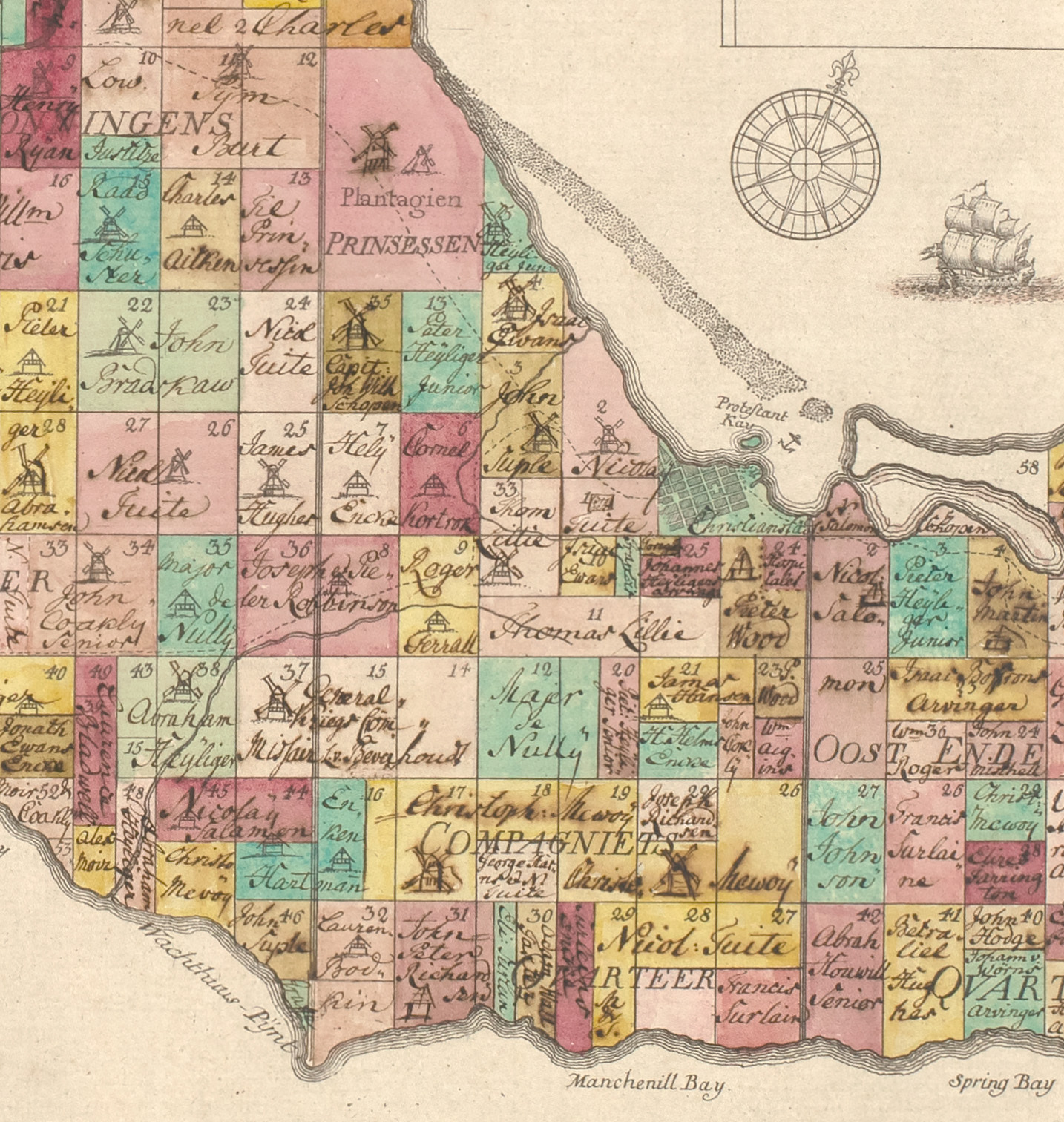

While Native Americans were pushed westwards, forced emigration peopled North America and the Caribbean islands with enslaved individuals. Despite or perhaps because of fears of the growing Black population, the African American presence as forced labor on plantations in the American South or the Caribbean islands was rarely visualized. However, one can discern the size of a plantation and extrapolate the number of slaves required to work in the fields or process sugar (the main export from the islands) from the plantation surveys frequently executed on the islands. A recent research project looked closely at the island of St Croix, a Danish colonial holding, and the depiction of two types of mills used for crushing the sugarcane: wind and animal driven. These mills were built and operated with Black labor, as the cartouche shows. The detail reveals the various sizes of plantations and the number of mills on each, a determining factor in the value of the holdings.

Hidden narratives of race, culture, and space lie under our noses as we study maps. Recent research on one of the Library’s prize atlases has illuminated a link to an annual celebration of historical events In San Pedro Huamelula, Mexico, in which the indigenous Chontal people reenact the invasion of Lan pichilinquis — the Chontal term for “pirates.”

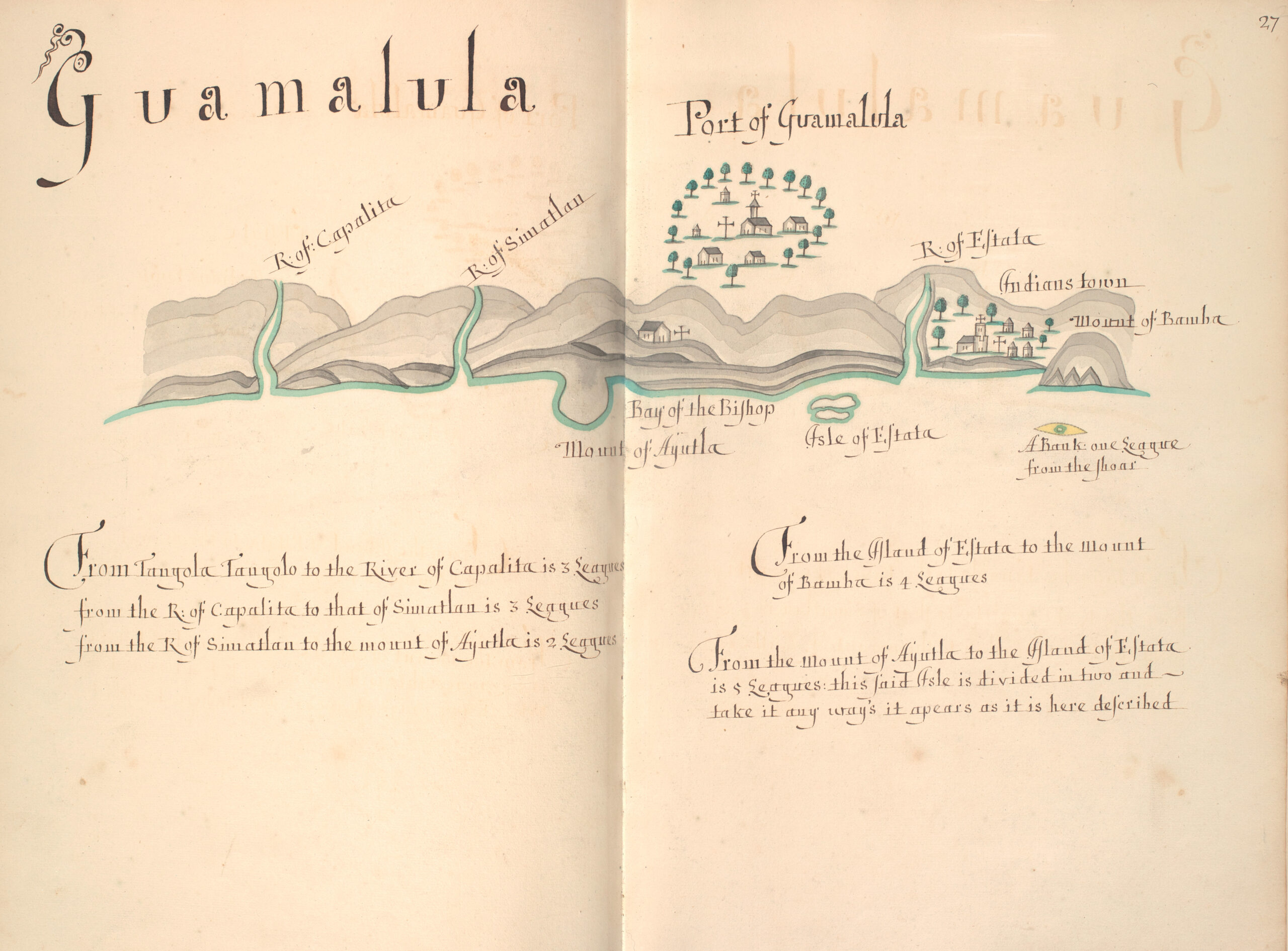

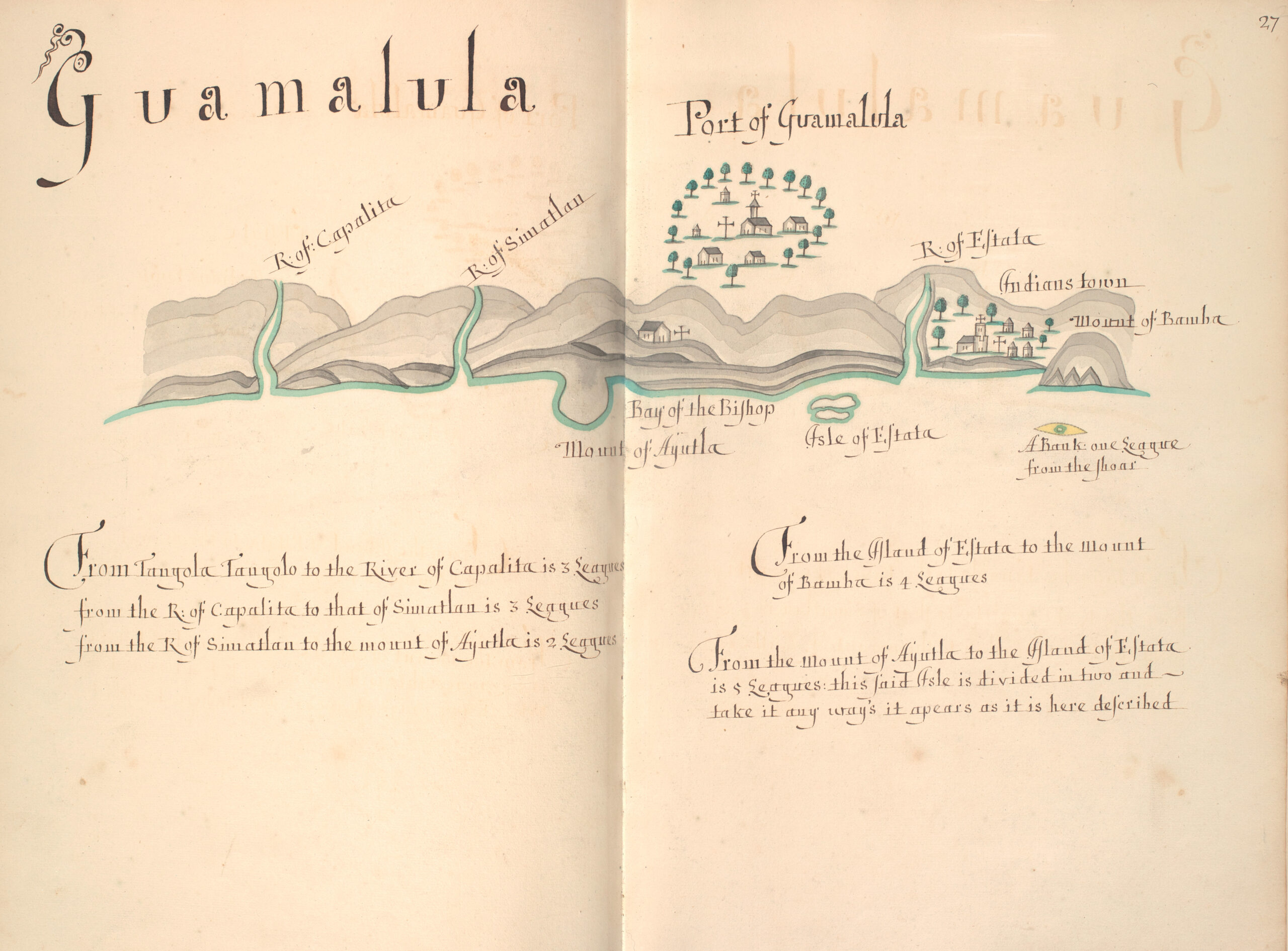

The pirates who invaded Huamelula may be linked to the buccaneer source of the one of the Library’s prize atlases: English chartmaker William Hacke’s atlas of 1698, a volume of 184 manuscript charts of the Pacific coast of America, one of at least 14 editions of this atlas produced in the 1680s and 1690s. The maps in the atlas were based on charts seized by English buccaneers in 1680 from a Spanish ship which were then requisitioned for their own raids on settlements up and down the Pacific coast, from Acapulco to Chile.

Throughout the Hacke Atlas (officially titled, “From the Original Spanish Manuscripts & our late English Discoveries A Description of all the Ports Bay’s Roads Harbours Rivers Islands Sands Shoald’s Rocks & Dangers in the South Seas of America,” hence the commonly used abbreviated title) are over a dozen brief references to various indigenous groups along the Pacific coast, noting who was friendly or hostile to the Spanish or English. Most of these “ethnographic” details do not appear in the original Spanish chart, as Spanish seafarers could typically rely on safe ports and bays controlled by the Spanish Crown; but competing English sailors were always concerned with the precise location of freshwater sources and isolated bays where ships could replenish and careen.

Jens Michelsen Beck, Tilforladelig Kort over Eylandet St. Croix Udi America ([Copenhagen], 1754)

Folio 27, “From the Original Spanish Manuscripts & our late English Discoveries A Description,” by William Hacke, 1698. Guamalula is present day Huamelula on the Pacific coast of Mexico.

On folio 27 of the Hacke Atlas, the Chontal community is glossed “Port of Guamalula” on the coast, although its location was and is inland; it is termed “Pueblo,” or town, on parallel Spanish atlases. Archaeological surveys have confirmed that this was the Chontal community’s original location, before pirate attacks forced the inhabitants to resettle further inland in the late 17th or early 18th century. This displacement is performed in the choreography of Huamelula’s annual reenactment, in which traditional Black characters may represent runaway enslaved Africans who sided with the Chontal to fight and repel foreign invaders. The roles of the reenactment festival echo historical identities of Chontal, pirates, and slaves—three disenfranchised but numerous groups who operated on the periphery of the Spanish Empire in a network of of competitive alliances, vying for land and trade.

The importance of using the past to understand the present cannot be underestimated. To quote Clements researcher, Danny Zborover, 2020–2021 Mary G. Stange Fellow, who brought the connection between the Hacke Atlas and the indigenous Chontal inhabitants of Huamelula to light and life: “by integrating archival research with interdisciplinary fieldwork and community outreach, the Clements Library’s Hacke Atlas and similar sources open a window into a fascinating yet untold story, one in which the Chontal and other Indigenous people contributed directly to the formation of the early Transpacific Modern World.” To paraphrase the ancient writer Cicero, our lives are woven from the threads of memory of previous times and peoples.

— Mary Pedley

Assistant Curator of Maps

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

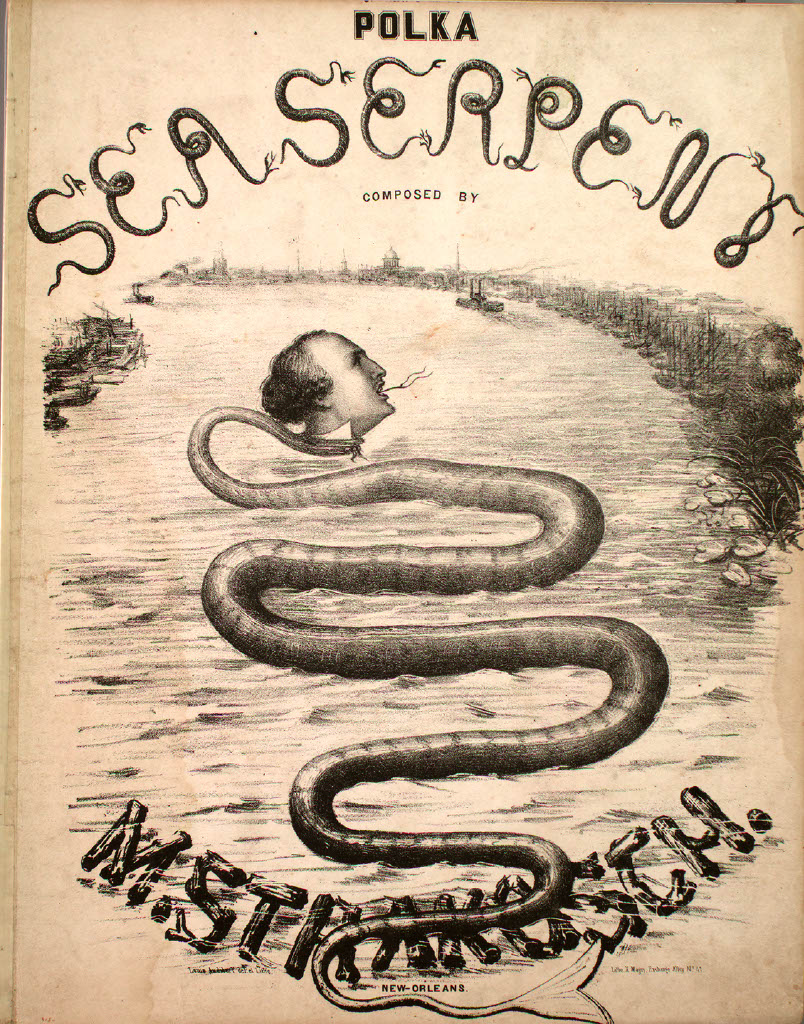

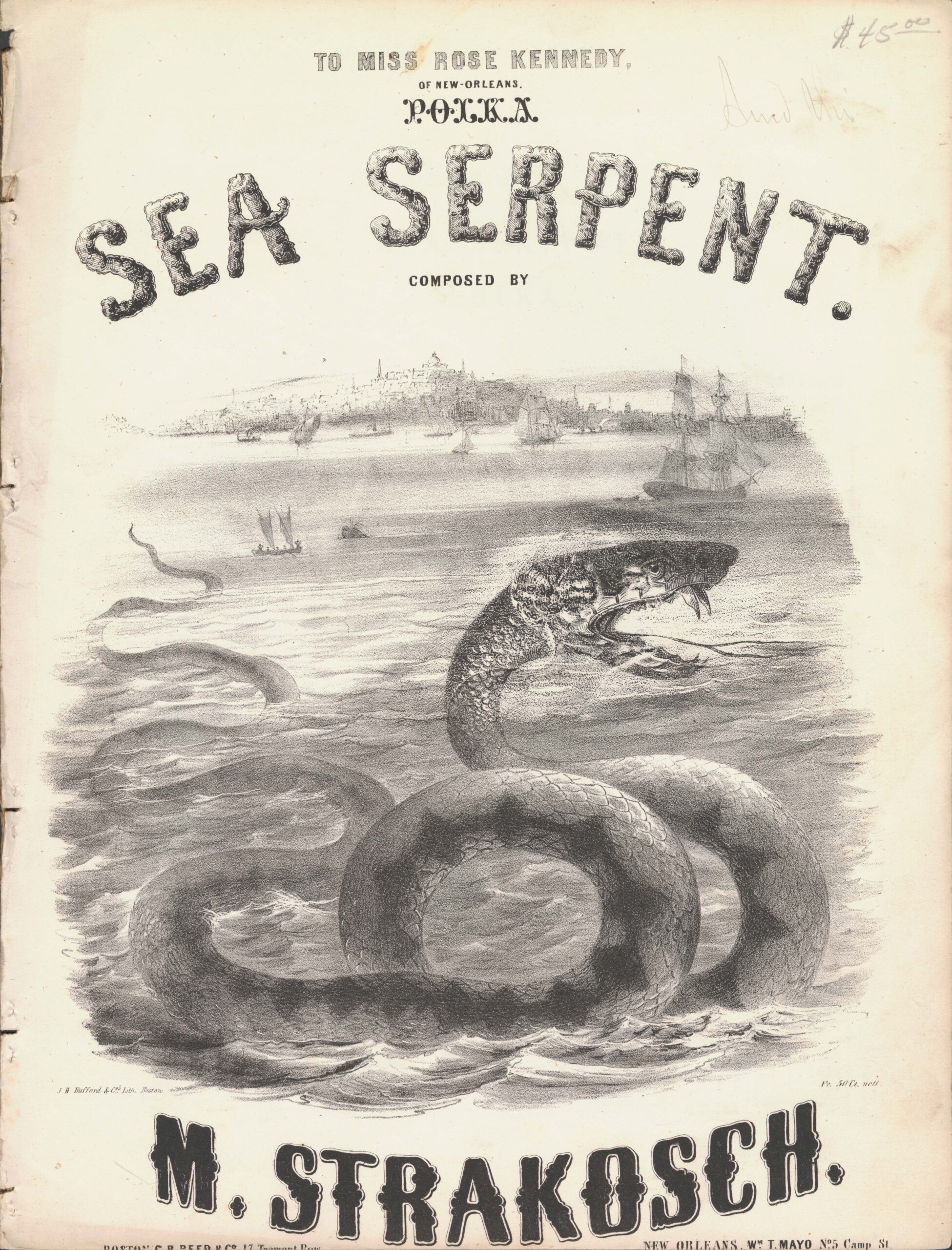

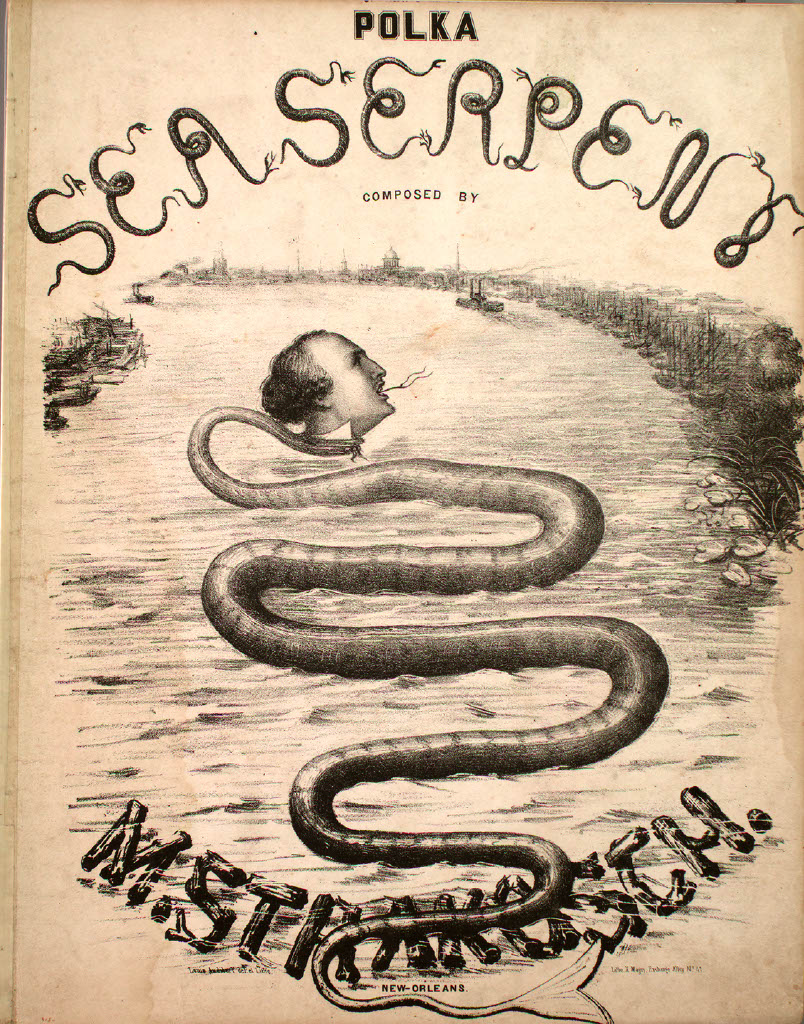

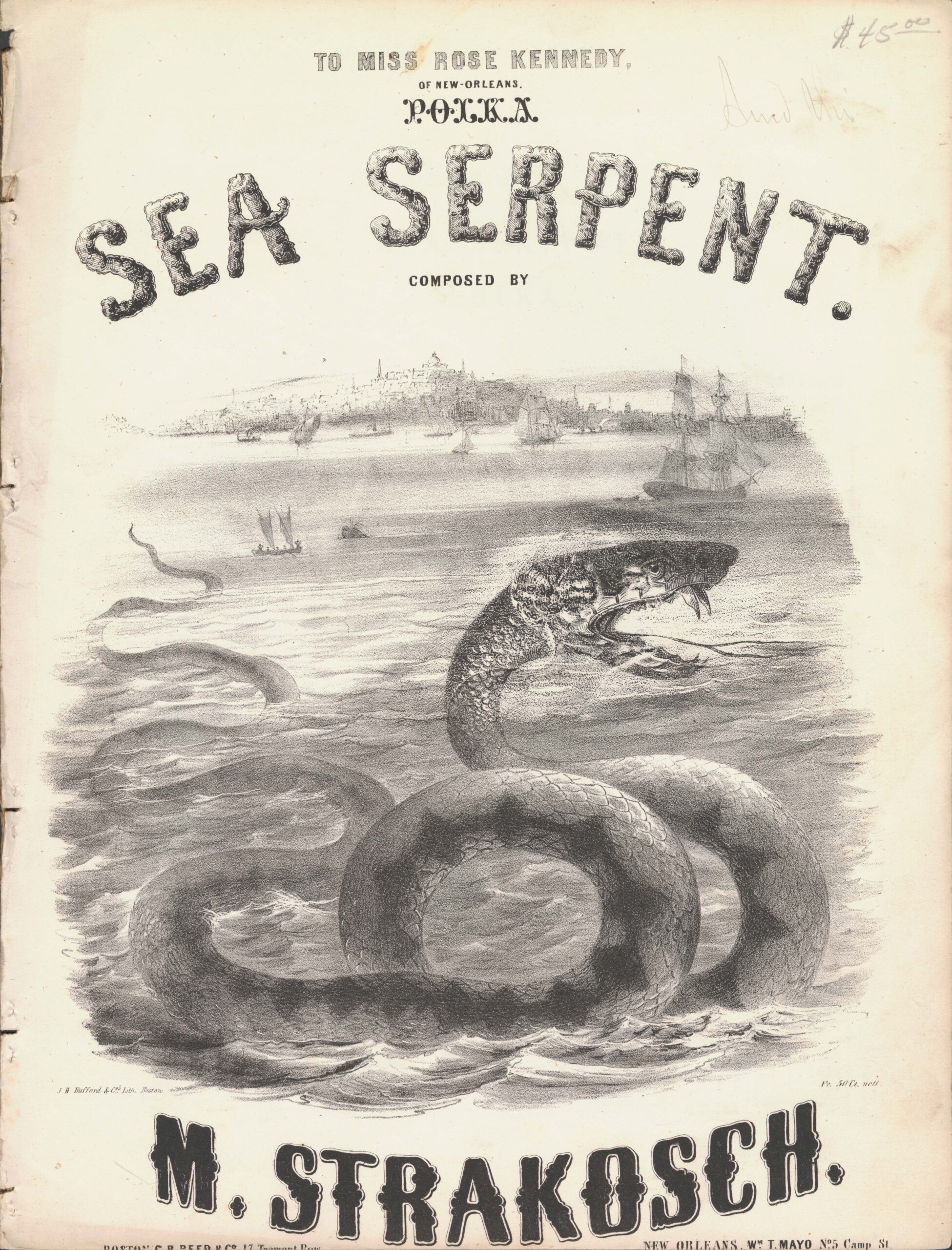

We all love sea serpents, and we all love mysteries. And a recently acquired example of great lithography ticks both of those boxes.

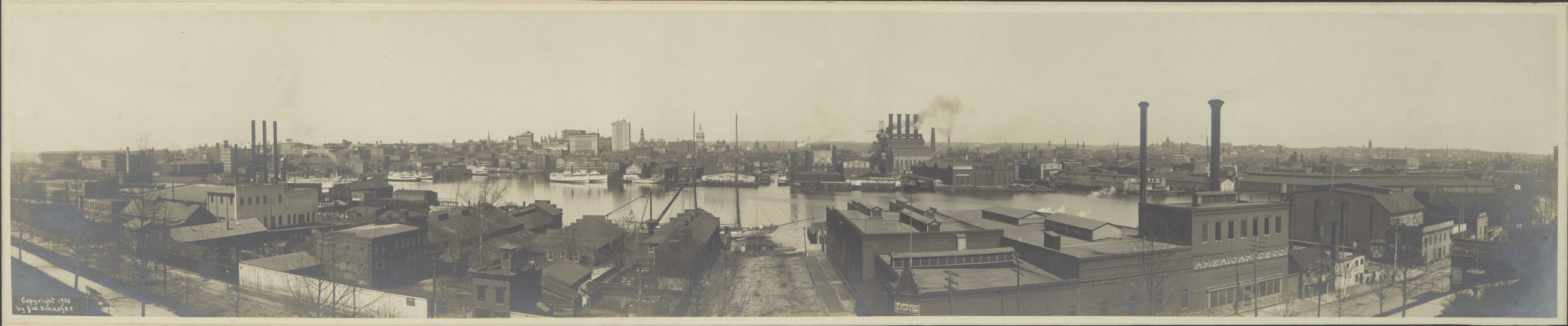

Sea Serpent Polka, composed by Moritz Strakosch (-1887). Louis Xavier Magny and Louis Audibert, lithographers. New Orleans, [1850s].

I was immediately attracted to this item because we have other prints and related stories of sea serpent sightings along the East Coast in the 19th century. This wonderful Sea Serpent Polka was printed in Boston by one of the great lithographers, John H. Bufford (1810– 1870), and was distributed by retailers in both Boston and New Orleans.

The lithographer has given us a nice view of Boston Harbor, with the State House as a backdrop at the top of the hill. But if you look at the head of the serpent, there’s a shadow of what could be another drawing, as if something had been altered in the production of the lithographic stone. And this is something you don’t often see, especially from one of the top lithographers in the business. There had possibly been another head on the sea serpent that had been erased and replaced with the present one. But the erasure hasn’t worked completely, and that intrigued me as an example of the printing process revealed by this sheet music cover.

The dedication at the top is to Miss Rose Kennedy of New Orleans, by Moritz Strakosch, a European composer who worked in America. After a little investigating, I learned that Rose Kennedy was the daughter of John Kennedy, superintendent of the United States Mint in New Orleans. Rose Kennedy’s debutante ball took place in the Mint, one of the great social galas of the year 1850. I have to guess that our composer Mr. Strakosch may have been there and been very impressed by Miss Kennedy, and hence this dedication.

I also found another version of this song. This is unfortunately not from our collection, but from the great Lester Levy Sheet Music Collection at Johns Hopkins University. It has a lot in common with the version above, only this was printed in New Orleans. The view of Boston has been replaced with a view of the Crescent City along the Mississippi. You can also see that the typography is different. But what catches your eye is that the serpent now has a human head. Some searching revealed that this bears a striking resemblance to a photographic portrait of the composer Maurice Strakosch. But why is he the serpent? And what exactly is his connection to Rose Kennedy?

Sea Serpent Polka, composed by Moritz Strakosch (-1887). J.H. Bufford, lithographer. Boston and New Orleans, [1850s].

This piece, I think, is a nice example of how the items in the Graphics Division can open up avenues of research as opposed to being the destination or an illustration for your research—it can be the starting point. I have as many questions as I do answers, but it’s been a delightful and fun project to explore.

— Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Material

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

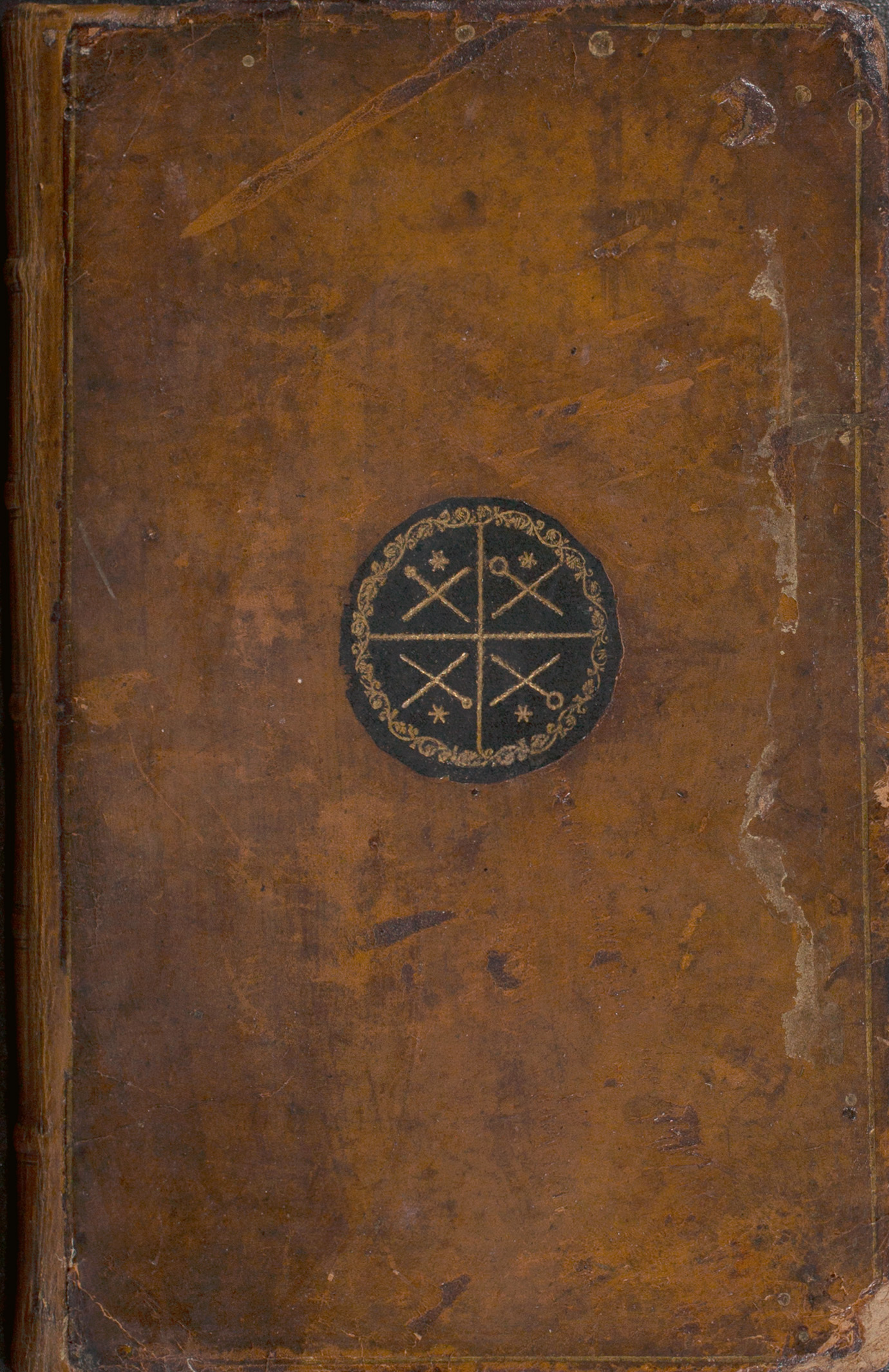

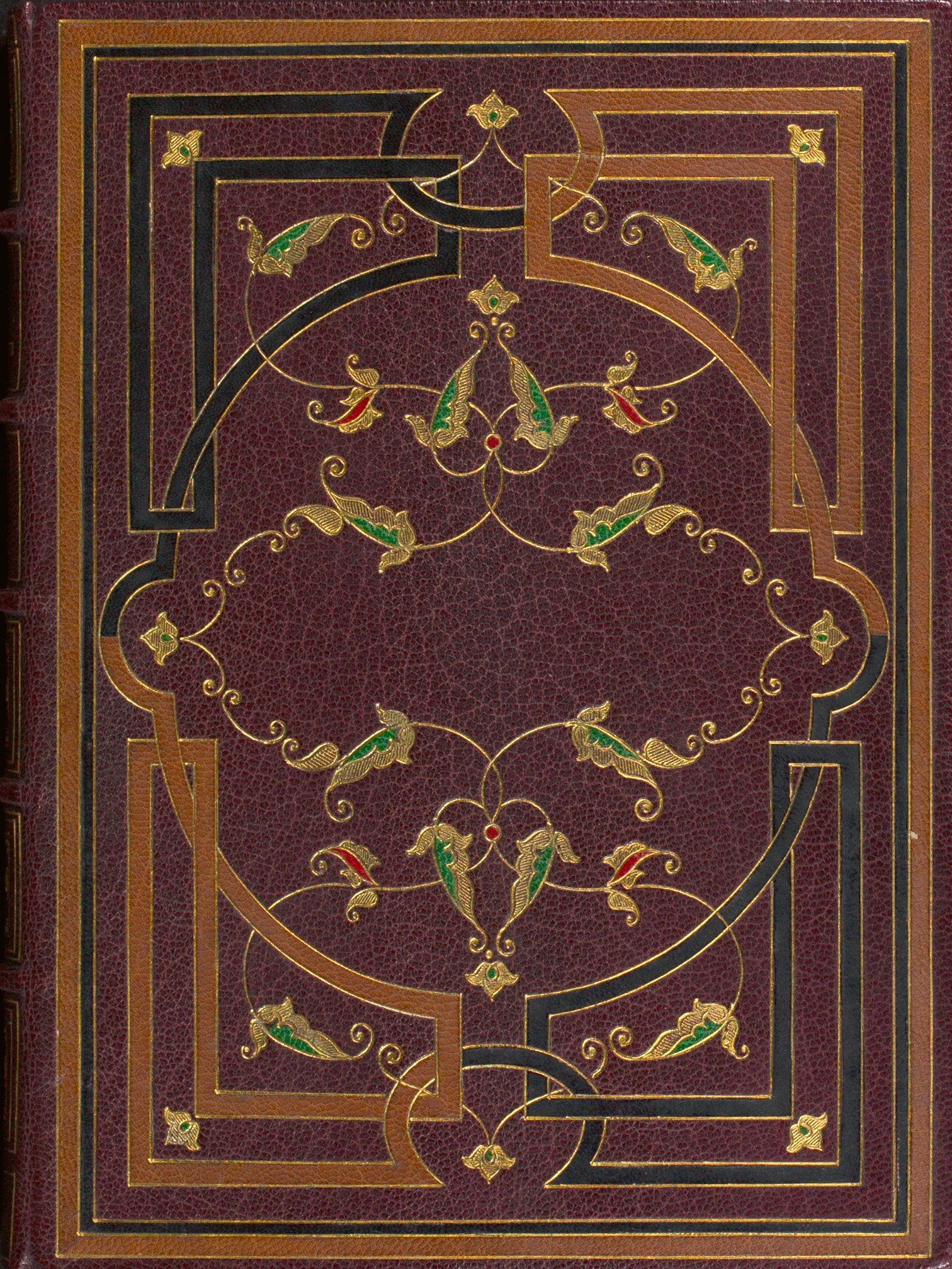

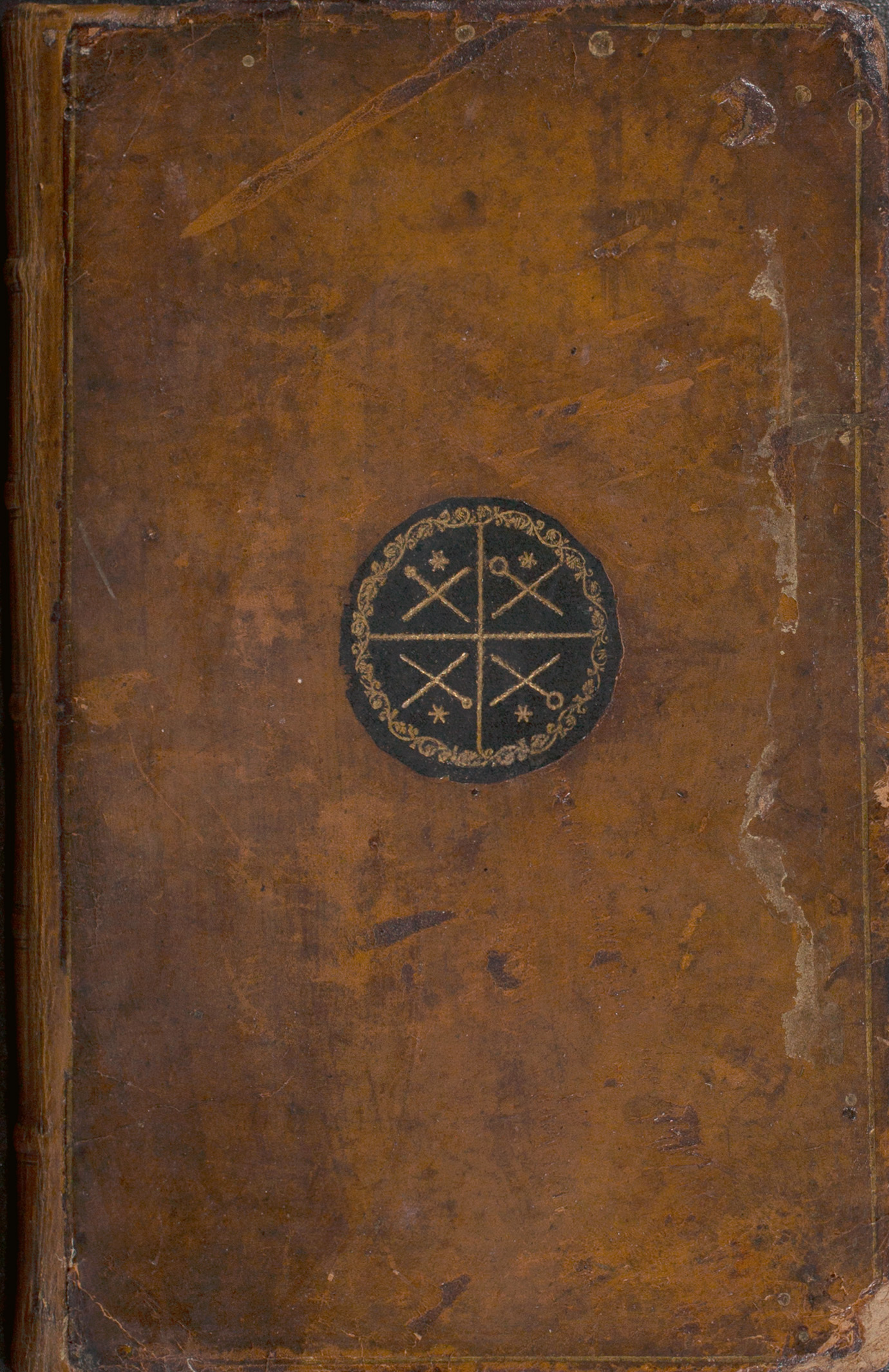

And what treasures to choose from! The Clements collection is a book collector’s (and binding historian’s) dream—William L. Clements eventually gathered an immense variety of binding styles, including many “extra” and fine bindings made by the most famous binders of his time and before, some original to the imprint, some as rebindings, including a Jean Grolier-style strapwork binding of great beauty, bindings done in Harleian and Etruscan style, and signed bindings by John Roulstone (1770 or 1771–1839), Christian Kalthoeber (active 1780–1817), W. T. Morrell, Robert Riviere (1808–1882), Sangorski and Sutcliffe, and Francis Bedford (1799–1883), among others.

Thinking about the exhibit as I write this reminds me of how things have changed with regard to historical bindings. Usually only the rarest, most expensive, and most beautiful bindings were ever seen; more pedestrian items, unless they contained a very important text or important illustrations, tended not to appear in binding exhibits. Today things are very different: there is abundant interest in the entire history of the book, and this includes not just content, but every aspect of a historical exemplar—the materiality of the book has come into its own. All aspects of the physical book, from paper type, writing and printing qualities, sewing and support structures, cover materials and decoration— all of these elements are examined, identified, described, protected—and shown. This revaluing of even ordinary historical bindings, once ignored, adds value to them in both monetary and intellectual ways—and influences the decisions collection managers make about them. Following are some favorites.

— Julia Miller

Author, Books Will Speak Plain: A Handbook for Identifying and Describing Historical Bindings, and Meeting by Accident: Selected Historical Bindings.

A Proposal to Determine our Longitude, by Jane Squire (1671?-1743). 2nd ed. London: Printed for the Author . . . , 1743.

Squire participated in (but was ignored) during the competition to find an accurate way to calculate longitude at sea. She may have failed, but her choice to decorate her book broke a convention long held by binding historians: book decoration did not reflect content before 1800. The black roundel on Squire’s cover, tooled with her invented symbols, did exactly that.

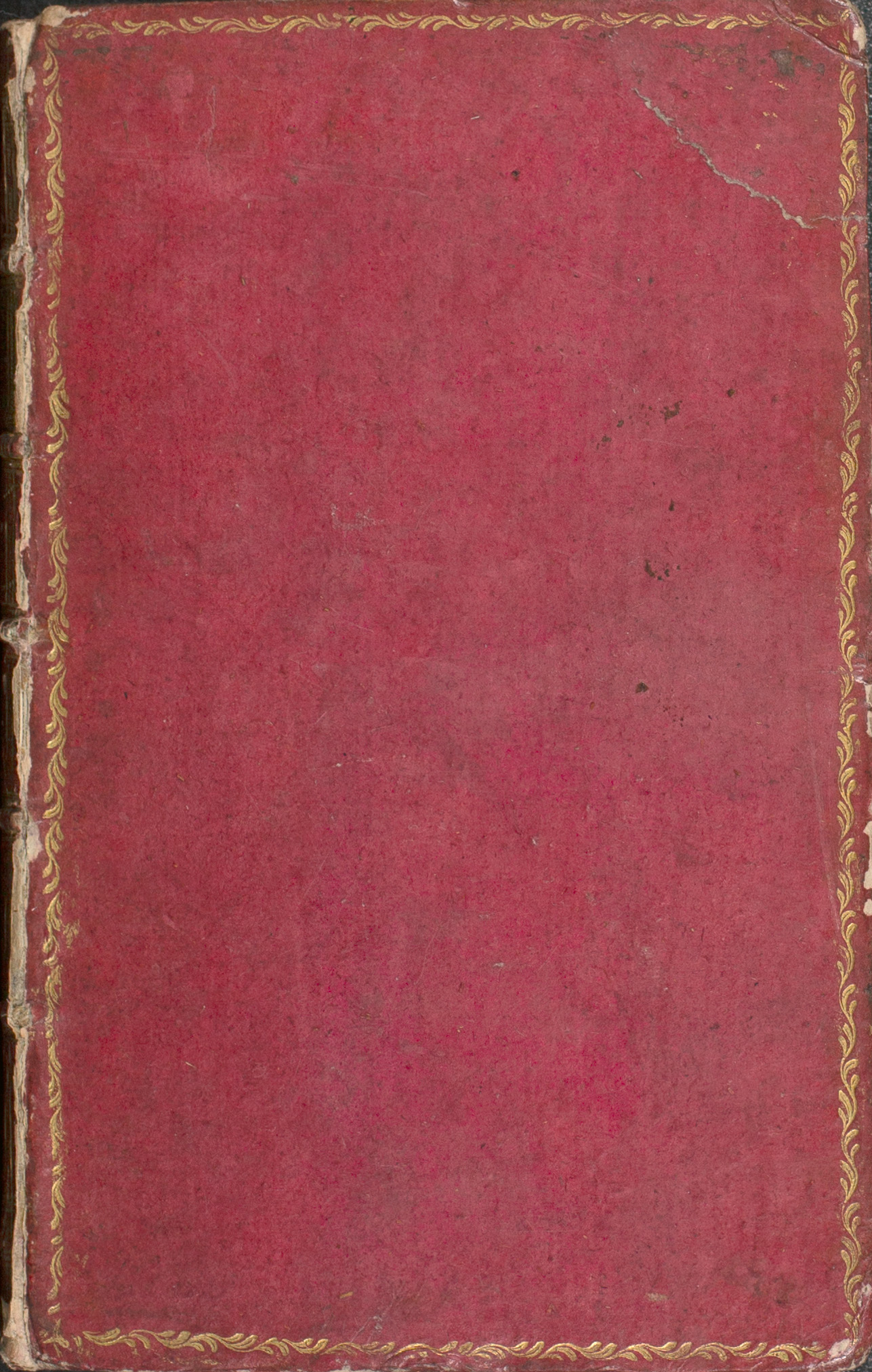

A Declaration of the People’s Natural Right to a Share in the Legislature . . . , by Granville Sharp (1735-1813). London: Printed for B. White, 1774.

A dark pink surface-colored paper binding, tooled in gold. Sharp was well known for his liberalism and anti-slavery beliefs—and his practice of having his arguments printed and bound up in such attractive (and relatively inexpensive) paper bindings—which he gave away.

The Book of Common Prayer . . . . New-York: By Direction of the General Convention, Printed by Hugh Gaine, 1795.

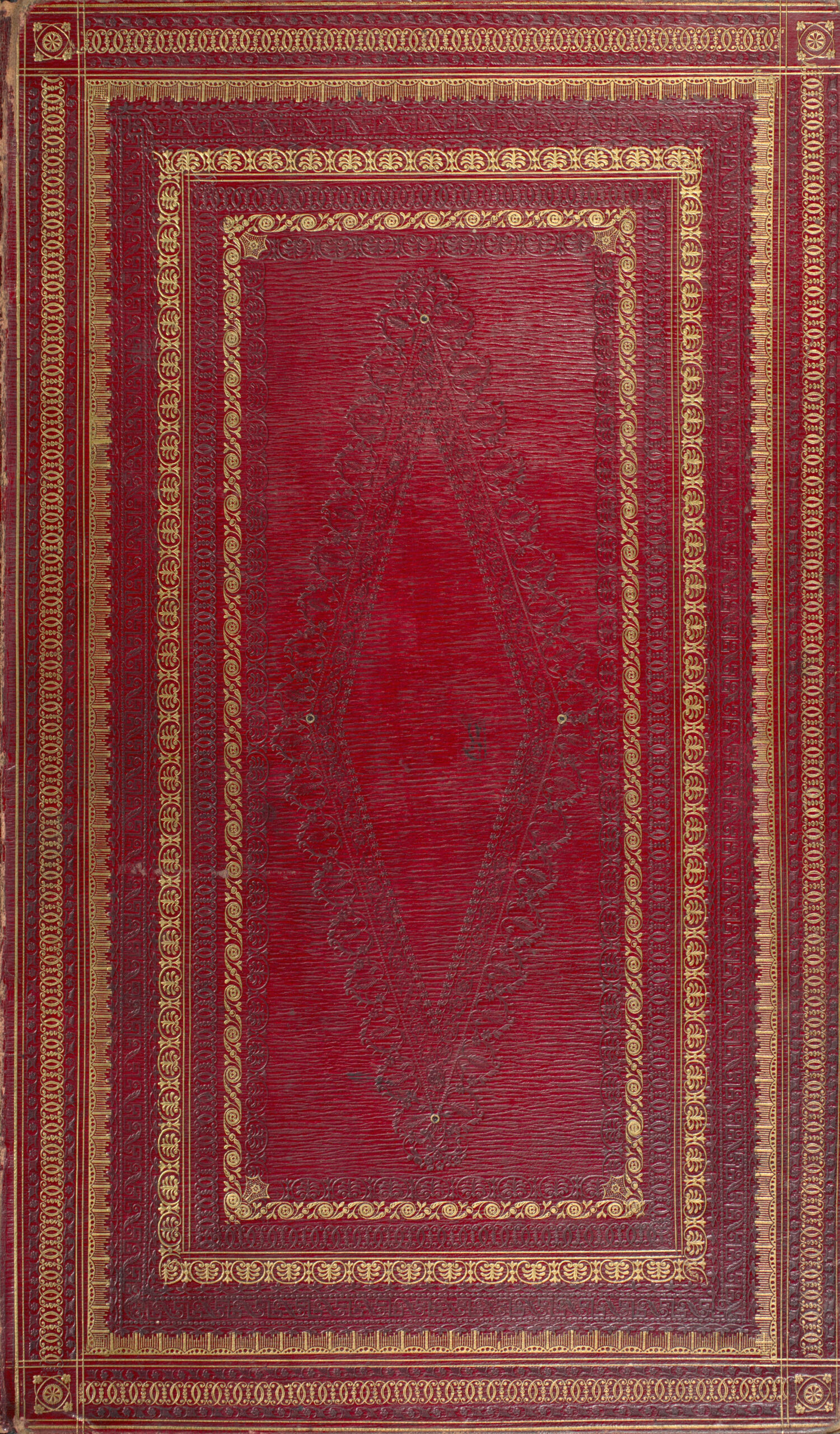

John Roulstone bound two copies of the Common Prayer, in identical dark-red straight-grained goatskin and signed both in gold inside the lower cover edge. Roulstone’s skill can be seen at once in the craftsmanship and tooling of this magnificent binding; he is arguably the best American binder of his era.

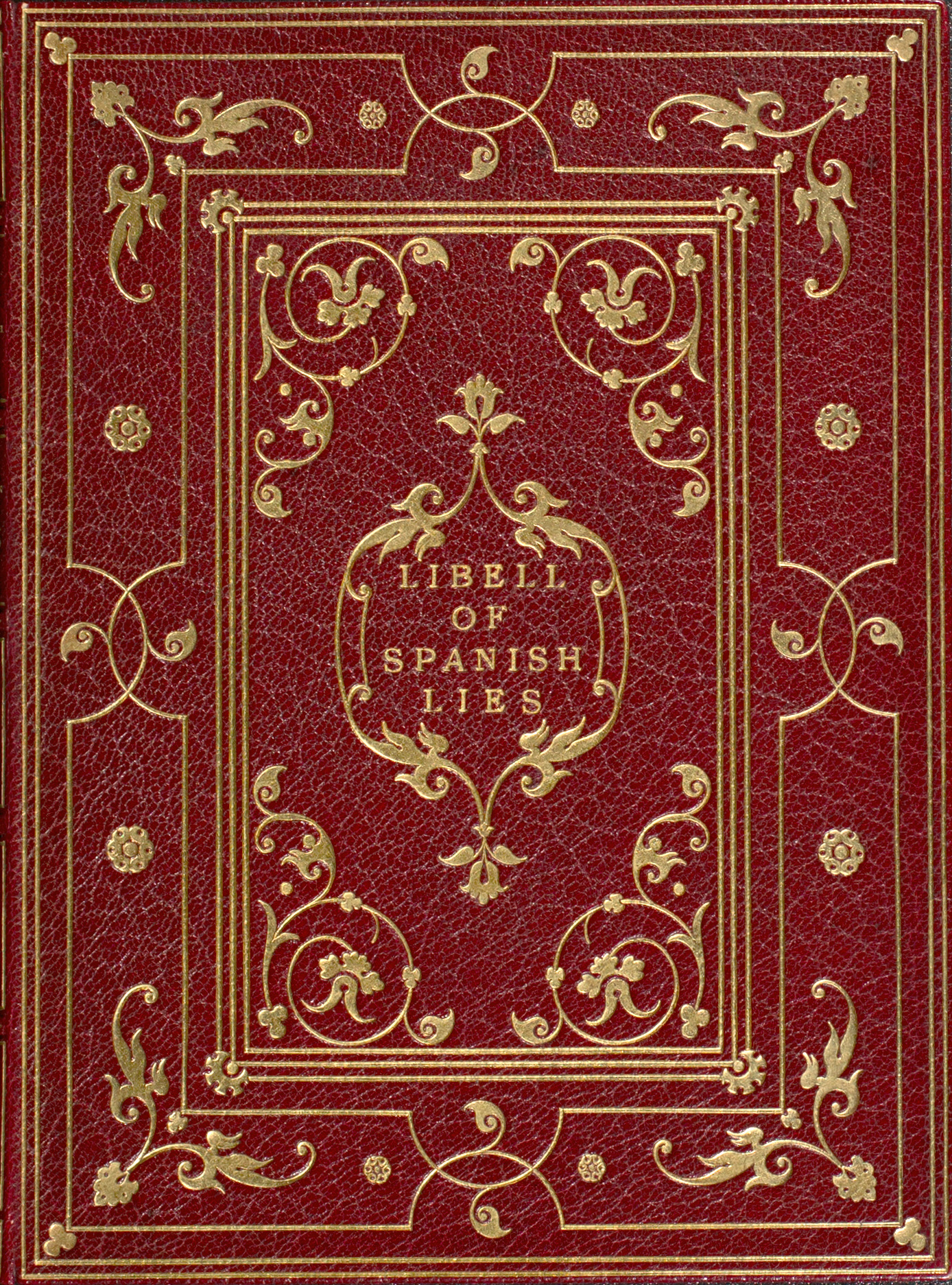

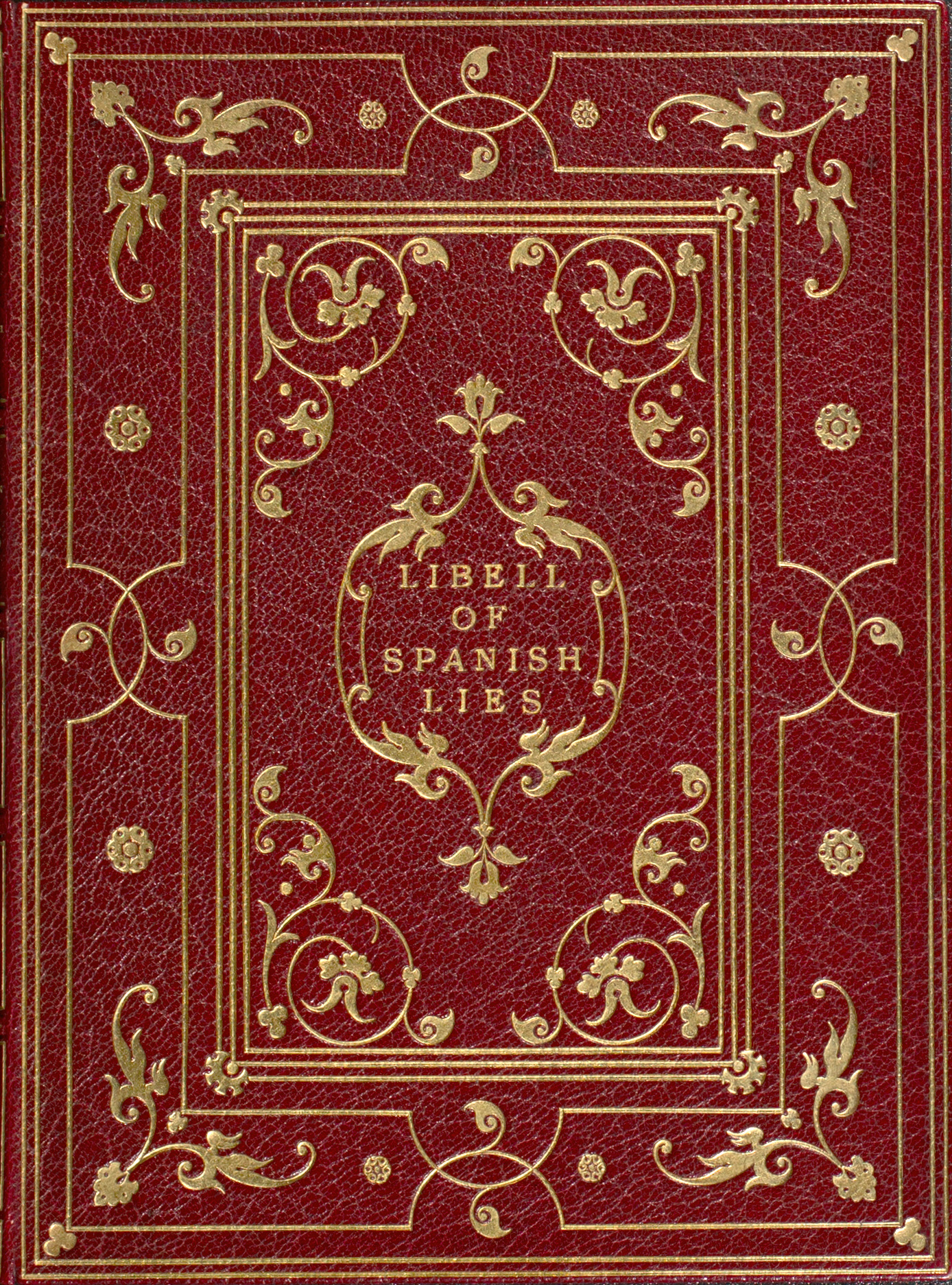

A Libell of Spanish Lies, by Capt. Henry Savile. London: Printed by John Windet, 1596.

Gold-tooled corner-and-centerpiece design, borrowing the famous Aldine Press centerpiece titling style; the Aldine style of titling became a vogue and is seen on some of Jean Grolier’s bindings. Bound by Rivière and Son, London.

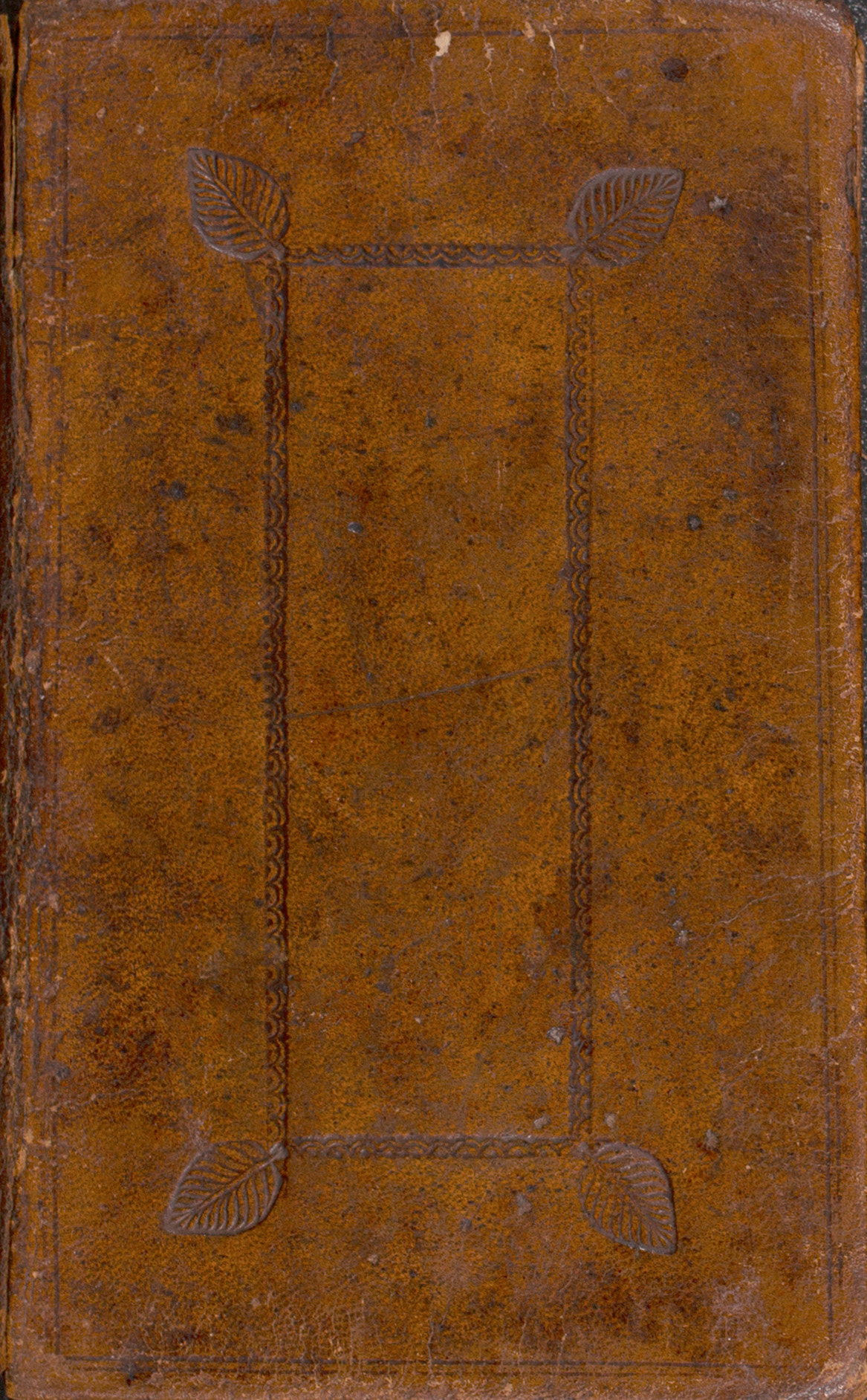

An Theater of Mortality, or, The Illustrious Inscriptions Extant upon the Several Monuments . . . , by Robert Monteith, M.A. Edinburgh: Printed by the heirs . . . , 1704.

A blind-tooled panel binding of sheepskin: a dot-andscallop roll used around the center frame, with an exquisite leaf-shaped fleuron tooled at the corners. The decoration is simple, well-executed and attractive.

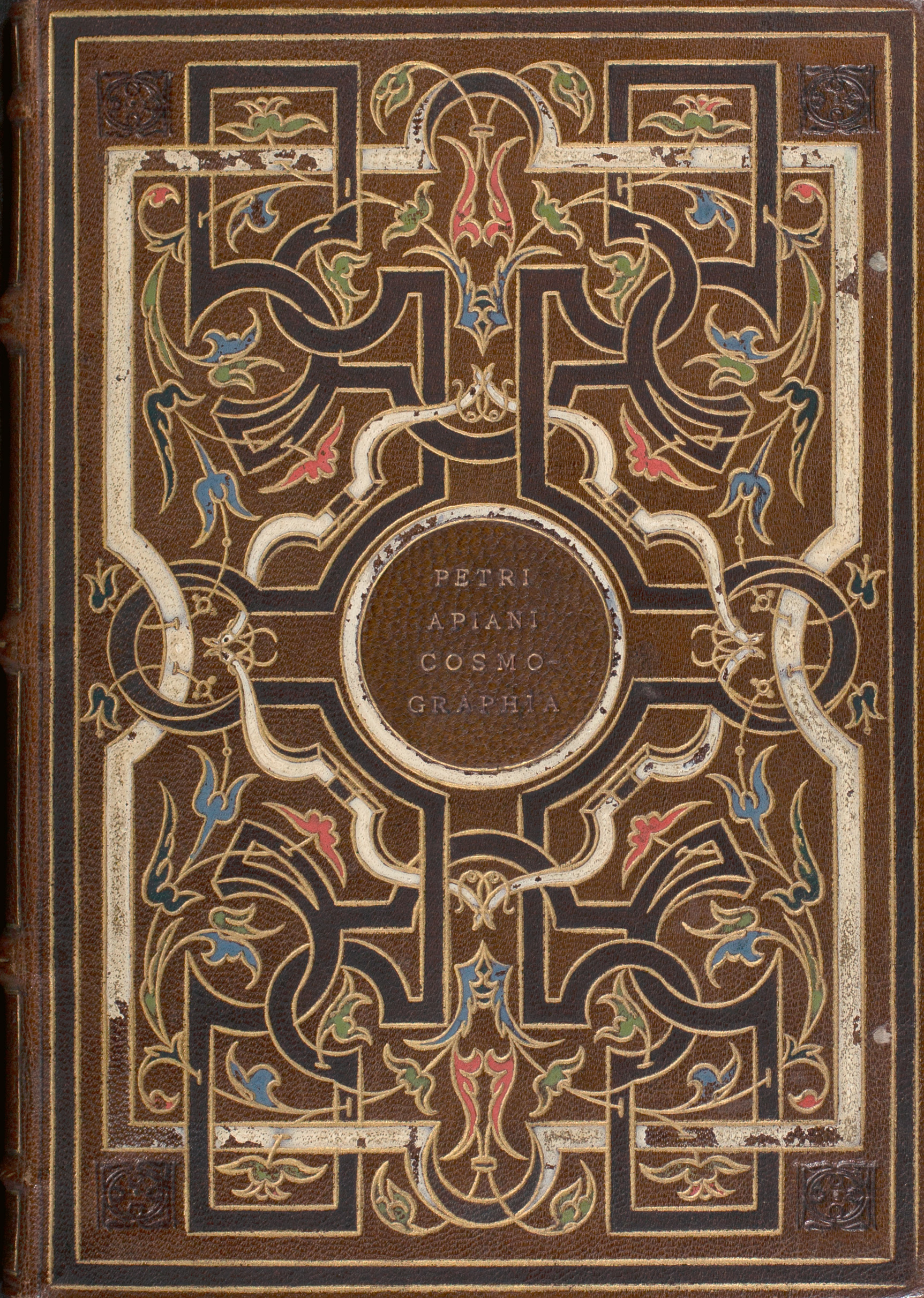

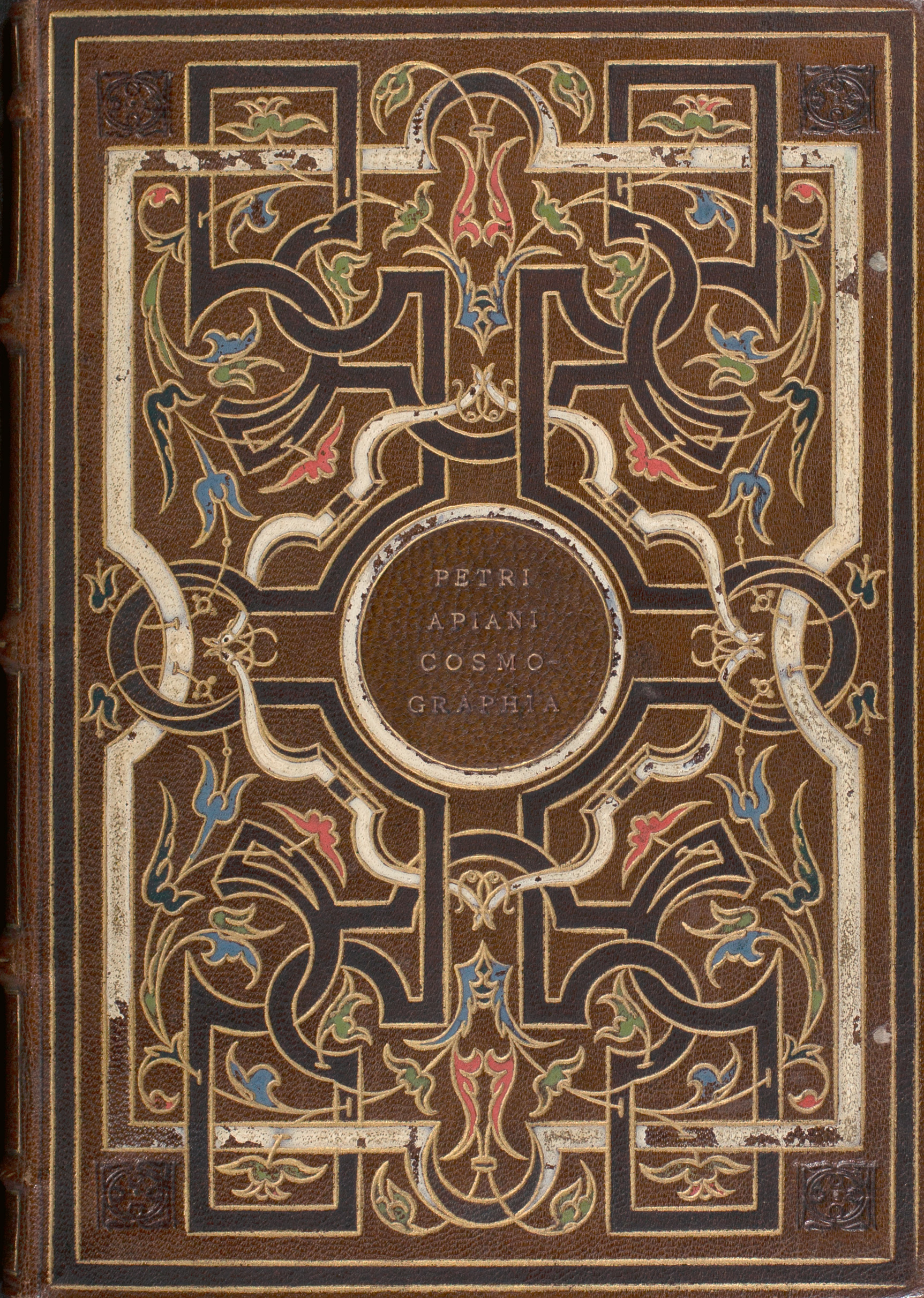

Cosmographia Petri Apiani, by Peter Apian (1495–1552). Antwerp: Gregorio Bontio, 1550.

Gold-tooled Grolier-style strapwork binding, the strapping painted white and black, with small touches of green, red, blue and black; gilt and gauffered edges are by Hagué.

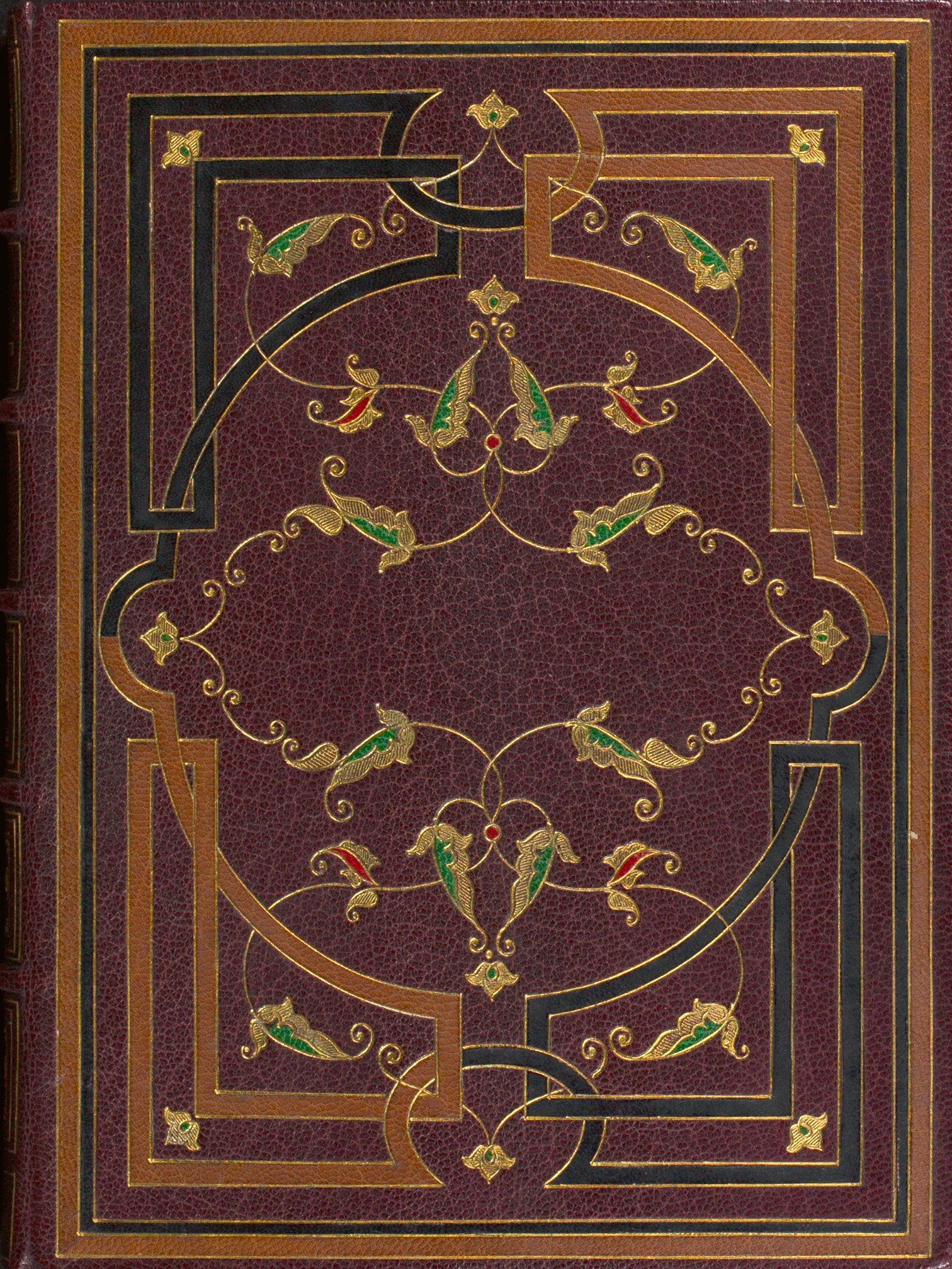

America Painted to the Life, by Sir Ferdinando Gorges (1565?–1647). London: Printed for Nath. Brook, 1658–1659.

Gold-tooled interlace strapwork design, employing azured tools and colored leather inlays. Bound by Sangorski and Sutcliffe, London.

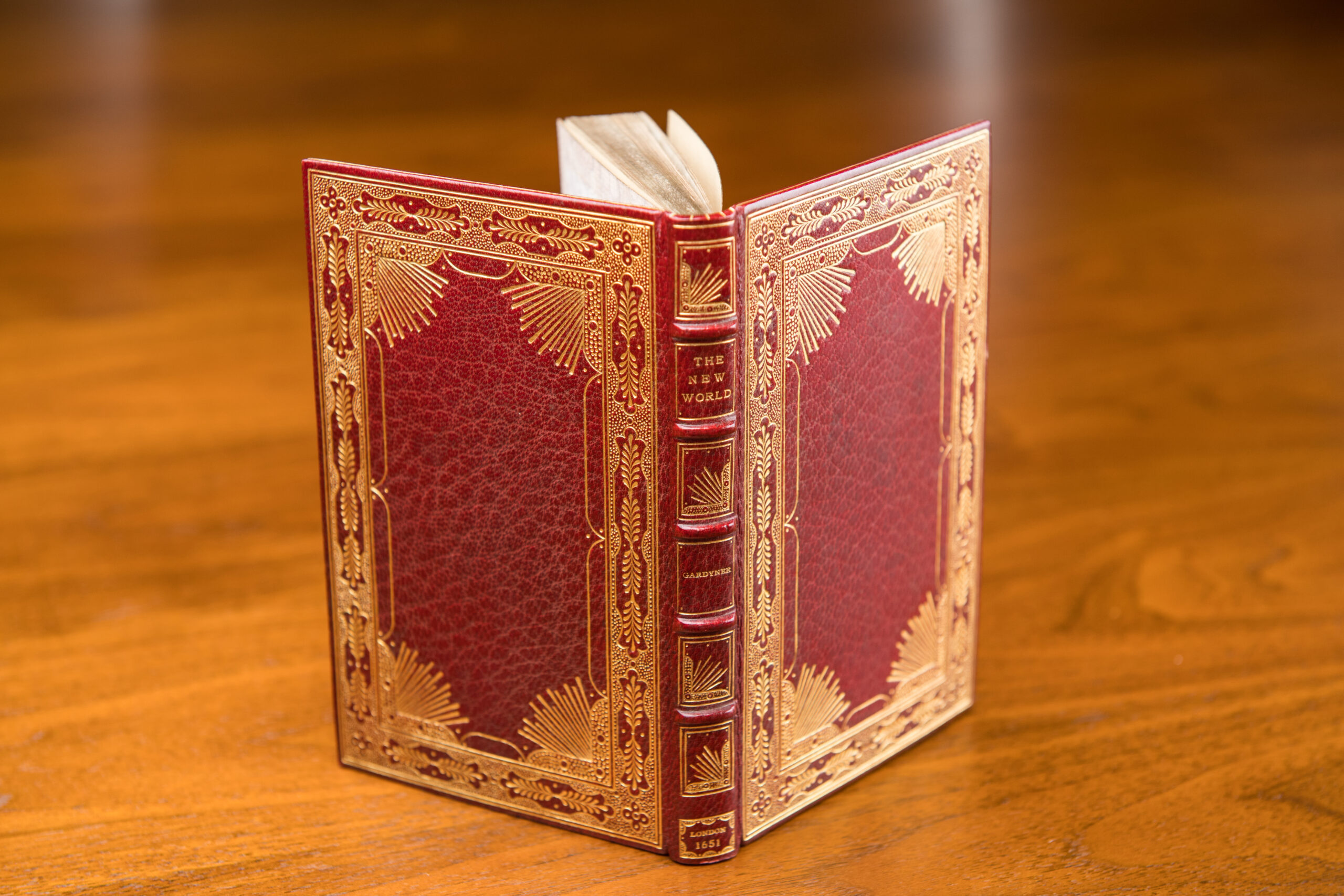

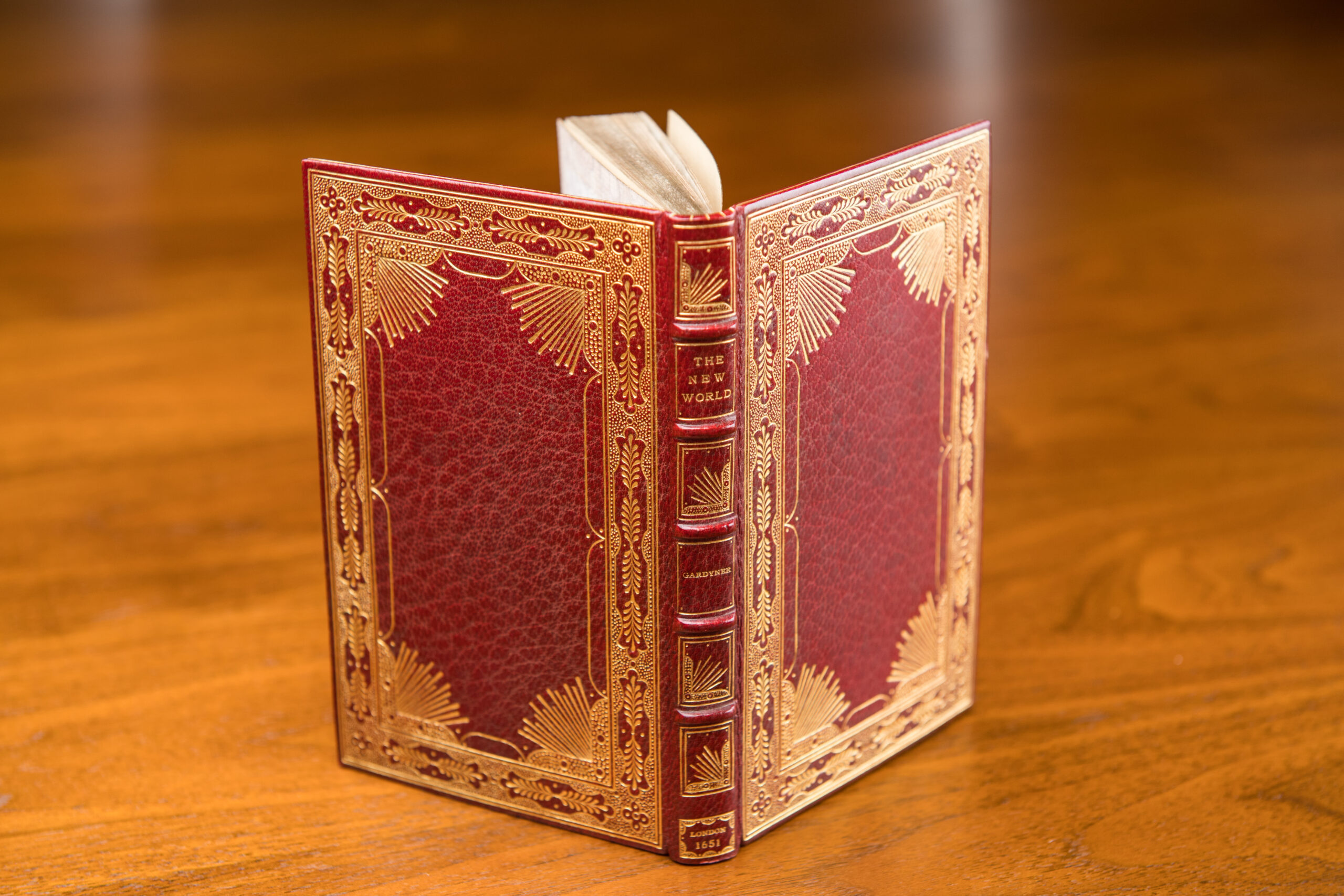

A Description of the New World, Or, America Islands and Continent, by George Gardyner. London : Printed for Robert Leybourn, 1651.

Exquisite gold-tooled cornerpiece style, combining quarter-fan corners and intricate panel borders filled with pointillé, by H. Zucker.

No. 57 (Winter/Spring 2023)

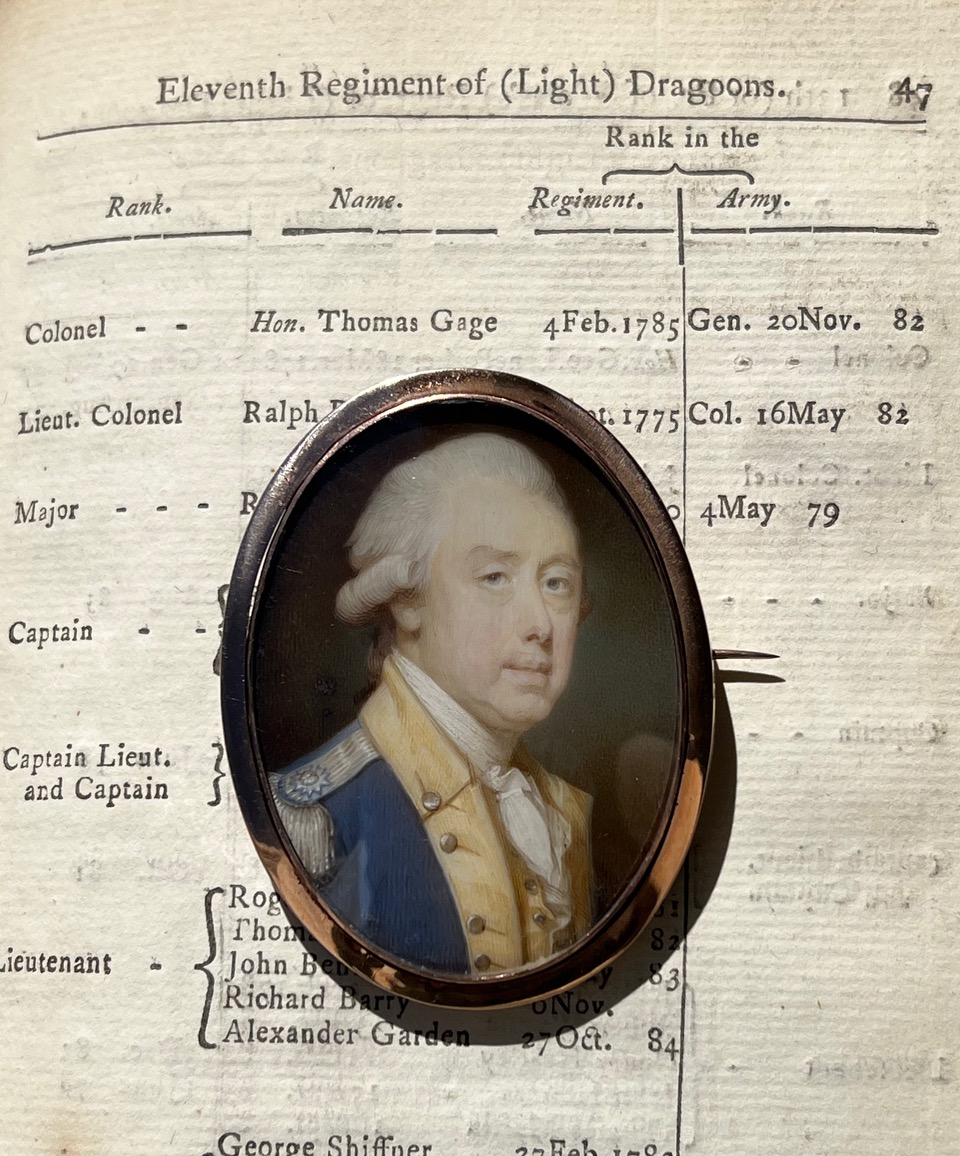

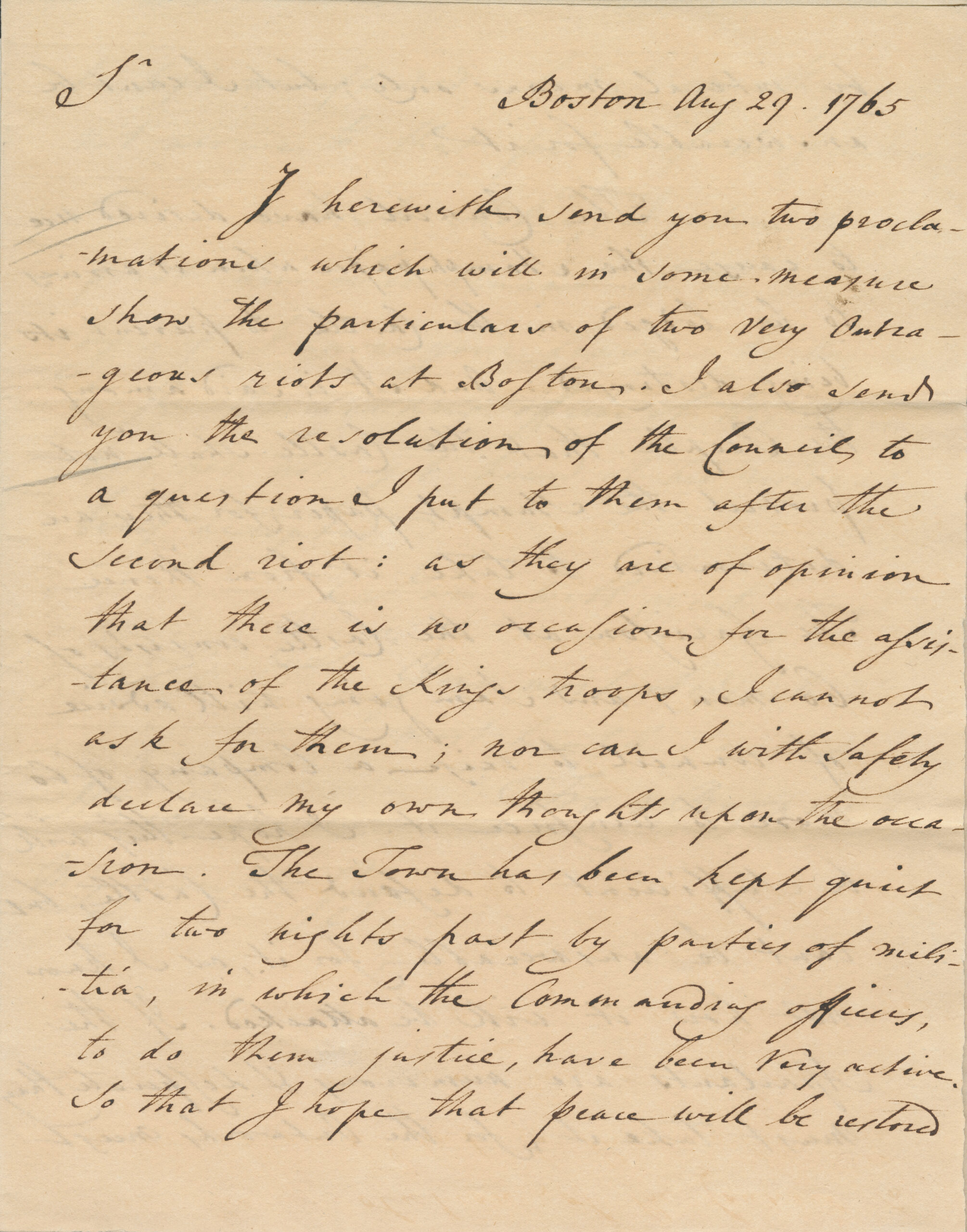

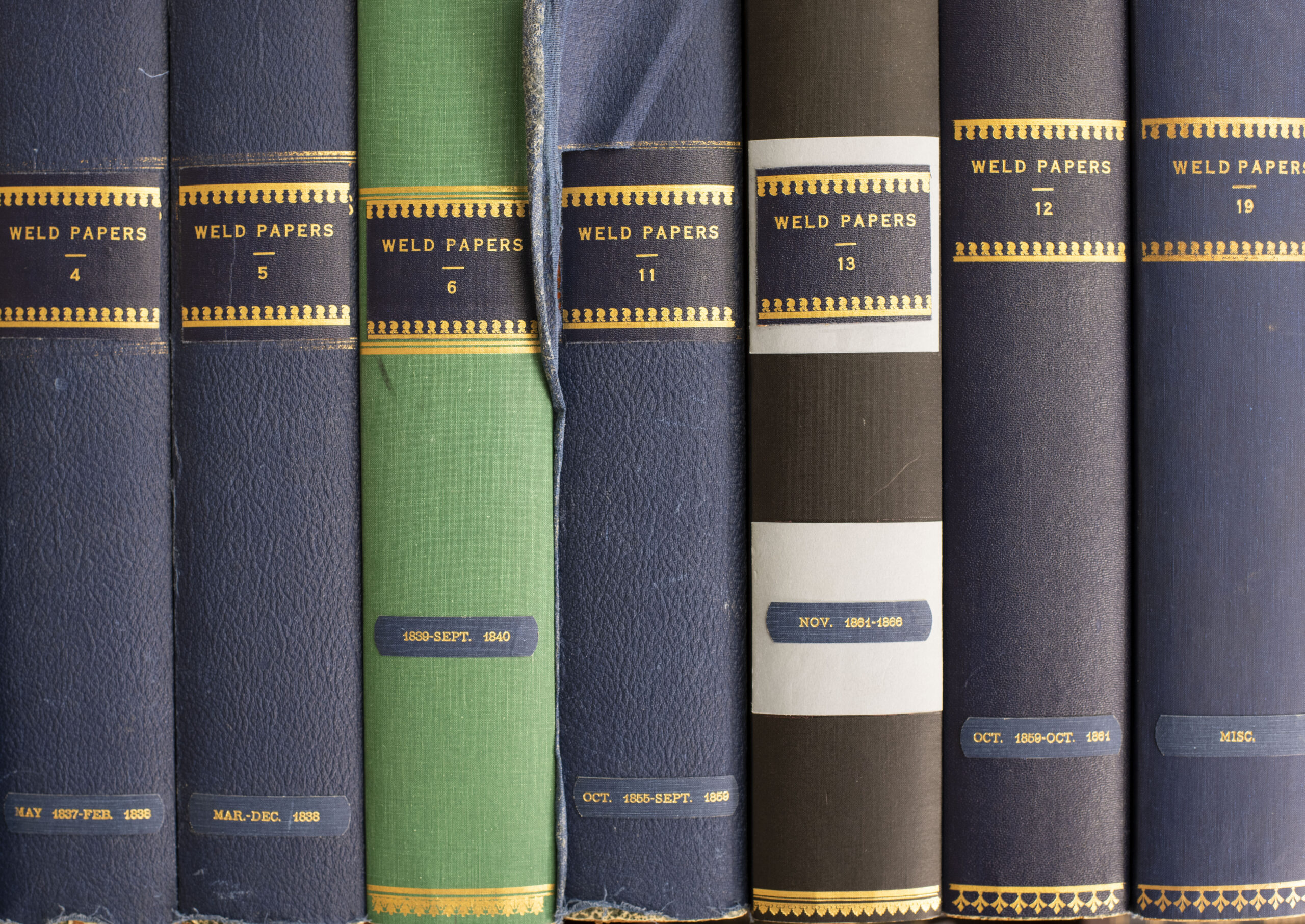

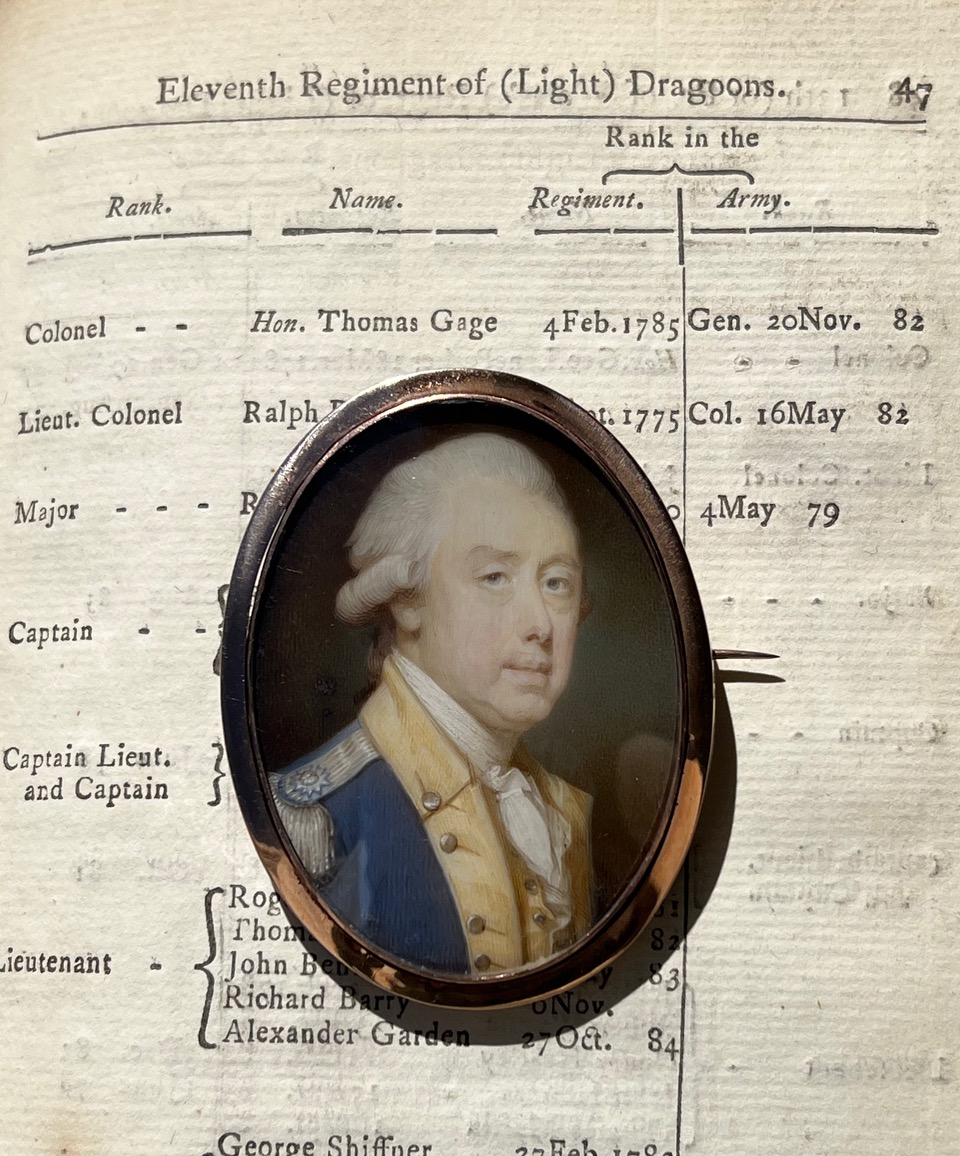

The papers of British General Thomas Gage have been the most queried, requested, researched, and otherwise utilized materials at the William L. Clements Library—from their arrival at the Library in 1937 to the present day. A National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant to digitize the Gage papers coincides with the Centennial of the William L. Clements Library. In keeping with a central tenet of the Clements Library’s mission statement, to “support and encourage scholarly investigation of our nation’s past . . . and make . . . materials available to students and the broader public,” the digitization of the Thomas Gage Papers will facilitate remote access to this internationally significant collection through freely available online publication.

The Clements Library is pleased to reveal this hitherto unrecorded 2¼” oval miniature portrait of Thomas Gage. He wears the uniform of the 11th Light Dragoons, the regimental coat indicating his colonelcy (held between 1785 and his death in 1787). Almost certainly Gage’s last portrait, his wife Margaret Gage may have worn it at least in the early period after her husband’s death. Painted by artist Jeremiah Meyer (1735–1789) on ivory, rose gold rim, pin back, necklace chain holes, cobalt blue backing, ca. 1785–1787. Discovered by Christopher Bryant and acquired by the Clements Library, 2022, thanks to the generosity of Benjamin and Bonnie Upton, and Margaret Trumbull.