Early American Interactions with the Barbary States

After gaining independence from Great Britain, the United States had little money to create and maintain a strong military. Under President Washington, Secretary of State John Jay chose to protect American merchant ships by negotiating with the Barbary powers.

Maintaining peace with North Africa, however, proved to be a perpetual struggle. The United States entered into several agreements with the Islamic powers of North Africa, including a treaty of peace with Morocco in 1786, a treaty that still stands today, treaties with Algiers in 1795 and 1796 (the latter, signed by Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, which curiously permitted Algerian privateers to hold Americans as slaves legally if they did not produce official passports), with Tripoli in 1796, and with Tunis in 1797. These treaties required that the United States pay expensive tributes of money, supplies, naval goods, and even warships.

Excerpt of Secretary of State [Timothy Pickering] Memo, before July 14, 1796:

This memo (pictured right) from Secretary of State Timothy Pickering concerns shipbuilder Josiah Fox’s inquiry for material needed in building a frigate for Algiers.

This Congressional document (pictured left) is a page from a longer report on the United States’ tribute payments to Algiers.

Despite the treaties and ever-increasing tribute payments, the Barbary pirates continued to capture American trading vessels. Ships captured included the Betsey, Dispatch, Dauphin, Hope, Jane, Jay, Maria, Mary, Minerva, Olive Branch, Oswego, Polly, President, Sophia, and Thomas, among others.

Privateers took the ships and cargo as prizes and enslaved the crew, stripped and chained them, and humiliated them in public parades. Finally, in 1794, Congress commissioned six frigates for Mediterranean use, and in 1798 approved establishing a marine corps. These efforts did not end the pillaging. In 1795, for example, America paid $1 million to Algiers for ransoms and tributes to ensure temporary peace, a sum that amounted to 20 percent of the country’s entire annual budget. By some estimates, between 1784 and the conclusion of the 2nd Barbary War (1815), the Barbary privateers captured almost 700 American citizens.

The Barbary threat also discouraged American travelers from entering the Mediterranean waters.

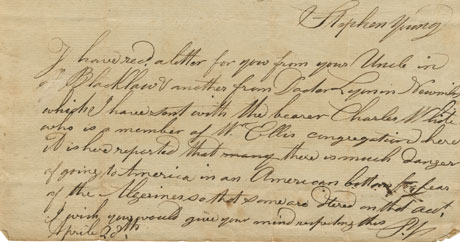

In a letter (on left) from the William Young papers traveler Stephen Young wrote to this brother William from Europe.

The pirates discouraged private merchants from attempting trade in the Barbary waters. Both the William L. Fisher papers (letter dated December 29, 1798) and the Grew Family papers (letter dated July 3, 1795) contain brief discussions of the risks faced by American trade companies that sent ships to the Mediterranean.

Other Pre-War Highlights

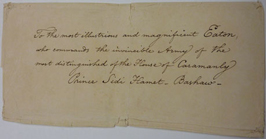

Sidi Hamet to William Eaton, September 15, 1800:

An envelope from Prince Sidi Hamet, Bashaw of Tripoli, to American Consul William Eaton.

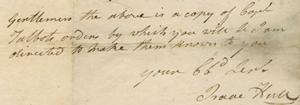

Isaac Hull to his Midshipmen, December 31, 1800:

Instructions from Captain Talbot, relayed through Captain Isaac Hull, describing methods for recording a ship’s course in the Mediterranean.