Land and Sovereignty

Resources

Contents

Land and Sovereignty: Ownership, Use, and Legalities

Struck in a Pose: Photographic Techniques and Romanticization

Myth Making: A Case Study on the "Hiawatha" Pageants

Complex Nationalism: A Case Study on the Minnesota Dakota War of 1862

Views of Assimilation: A Case Study on Photography in Indian Boarding Schools

Ownership, Land Use, and Legalities

Sovereignty: The right or authority for a body to govern itself, without interference from others. Tribal sovereignty refers to the fact that the U.S. Constitution recognizes American Indians and Alaskan Native tribes as distinct governments, with rights on par with state or federal governments depending on context.

Settler Colonialism: This form of colonialism involves large scale immigration to a new region with the goal of replacing any existing populations with a new society of settlers. It can involve any combination of violent depopulation and assimilation tactics.

The Self and Representational Sovereignty

While sovereignty is commonly associated with nations, the freedom of an individual to self-define and self-govern are staples of sovereignty as well, particularly given that there is no one way to be ‘Indian.’

These two full length portraits of Chief Shopp-en-a-gon from Grayling, Michigan demonstrate how expectations of Indigenous authenticity and identity were, and still often are, based on non-Indigenous definitions. Photography helped highlight and sometimes dissolve this divide.

Chief David Shopp-en-a-gon

George H. Bonnell

Cabinet photographs, ca. 1890

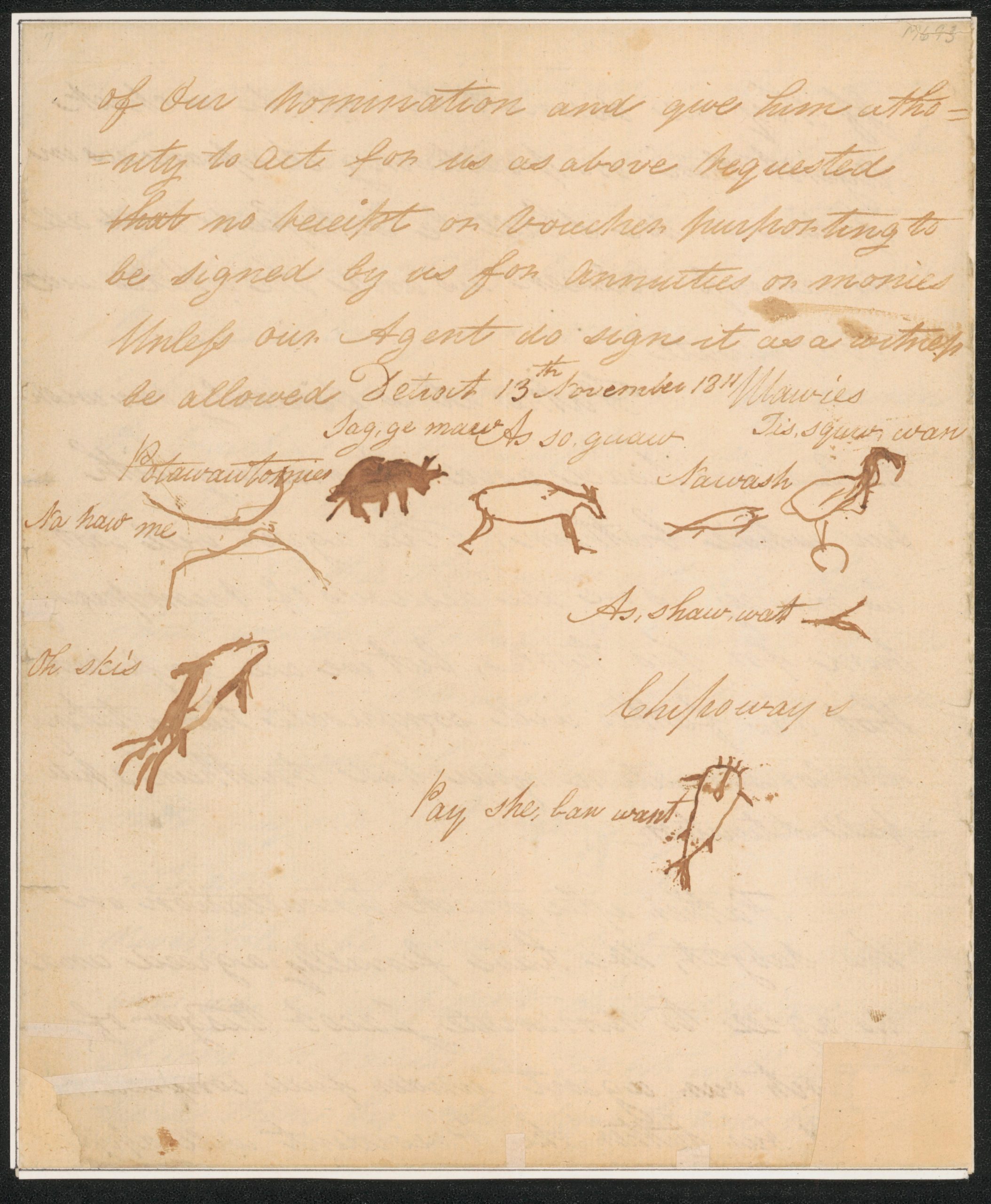

Inscribed into a different medium, this letter to President James Madison was co-authored by members of Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Wyandot, and Miami tribes in 1811. It focuses on the impending war between the United States and England (the War of 1812), its effect on treaty provisions, and it responds to Madison’s calls to have the tribes support the U.S. in such a war.

The heavy use of poetic metaphor in this letter enables the tribes to reference trauma caused by settler policies, threats, and violated treaties without being explicitly pointed. One metaphor reads: “White people appear fond of feathering their own nest and often plucking the red birds for the purpose of accomplishing their purposes” and masks intense violence against Natives through the quotidian image of birds.

Similar to the written metaphors, the marks signed by individuals of these four tribes provide an example of a profoundly different way to communicate self-identity than the portraits of Chief Shopp-en-a-gon . These marks are powerful examples of representational agency and sovereignty already in practice before photography.

Letter to President James Madison

Members of Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Wyandot, and Miami tribes

Autographed letter, signed, 1811

Lewis Cass Papers

Ownership, Governance, and Legal Sovereignty

How to relate to, allocate, and use land is perhaps one of the most defining questions plaguing Indigenous and European settler relations. In addition to disagreements over certain geographic regions, Euro-American concepts of private ownership clashed with many tribes’ practices of communal use. During this time, communally stewarded spaces were allocated to private individuals and territorial boundaries solidified around the Great Lakes (and elsewhere). Natives and non-Natives alike set new rules to govern the use of land and assert sovereignty.

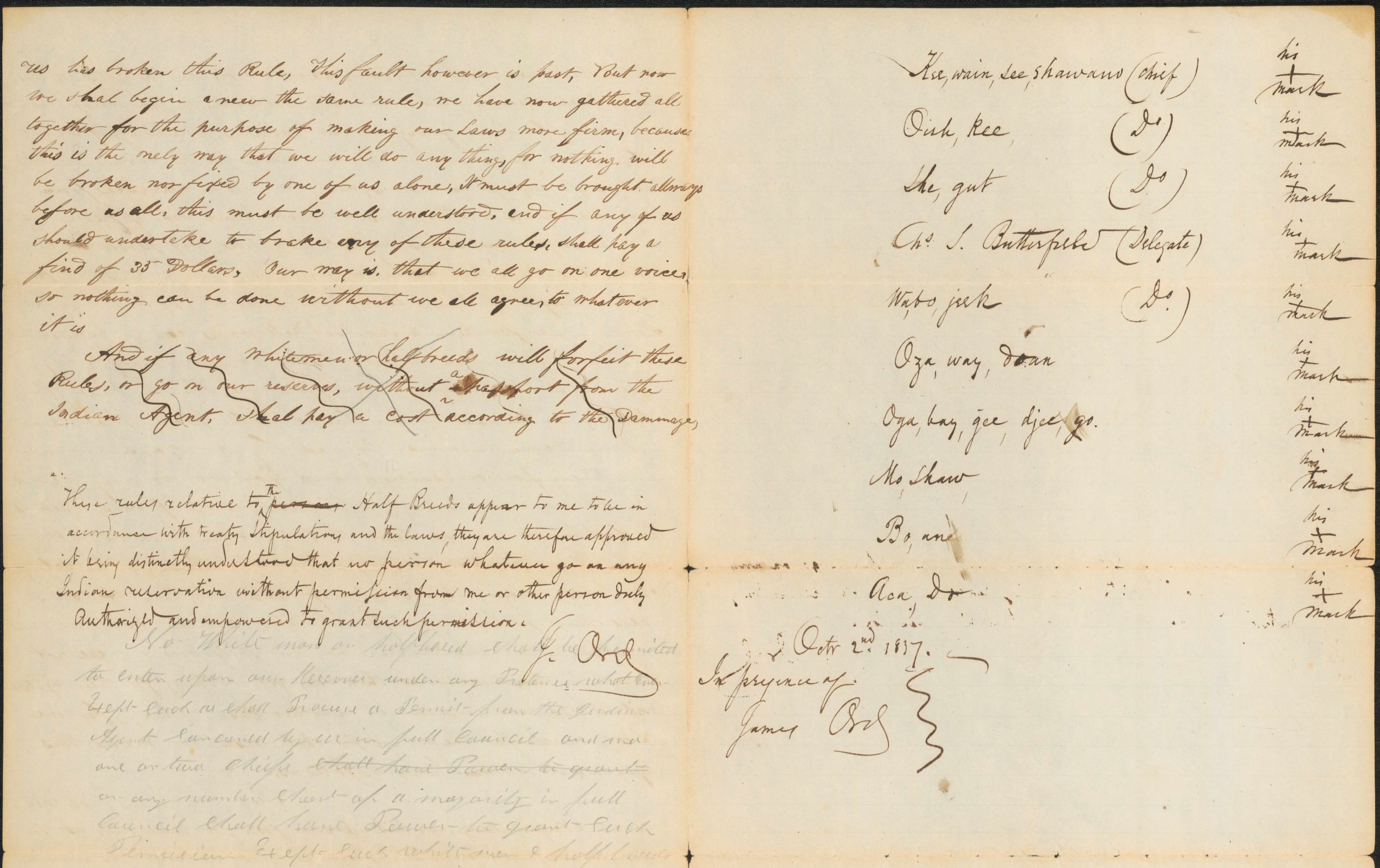

Signed in 1837 with the marks of 10 Anishinaabe, including Chief Kee-Wain-See-Shawano and other delegates, this document speaks to the difficulties of land stewardship under new concepts of ownership.

Chief Kee-Wain-See-Shawano, et al.

Agreement limiting hunting and fishing rights, October, 2, 1837

John M. Johnston collection

The delegates wrote in one voice, detailing their united jurisdiction over use of their land. It identifies issues of Euro-Americans trespassing in reserve territories and outlines clear rules regarding hunting and fishing rights for Natives, non-Natives, and “half-breeds*” alike. The style of signatures is markedly different from the four tribes letter to Madison and speaks to how fast written and visual cultures were changing just before and alongside the invention of photography.

Fishing rights and canoe sales feature prominently in the 1837 document signed by Kee-Wain-See-Shawano, as birch bark canoes are well suited for the Great Lakes region. In photos such as the following, stereograph photographers composed their pictures to include dramatic foreshortening and depth to heighten the three-dimensional effect. Here, the body of the birch bark canoe creates that affect. It draws the viewer’s attention down the gunwale and leads to a pair of unidentified Ojibwe men crafting a second canoe just behind.

As removal policies became more aggressive and land became even more policed, government treaty provisions constrained some, though not all, of these practices.

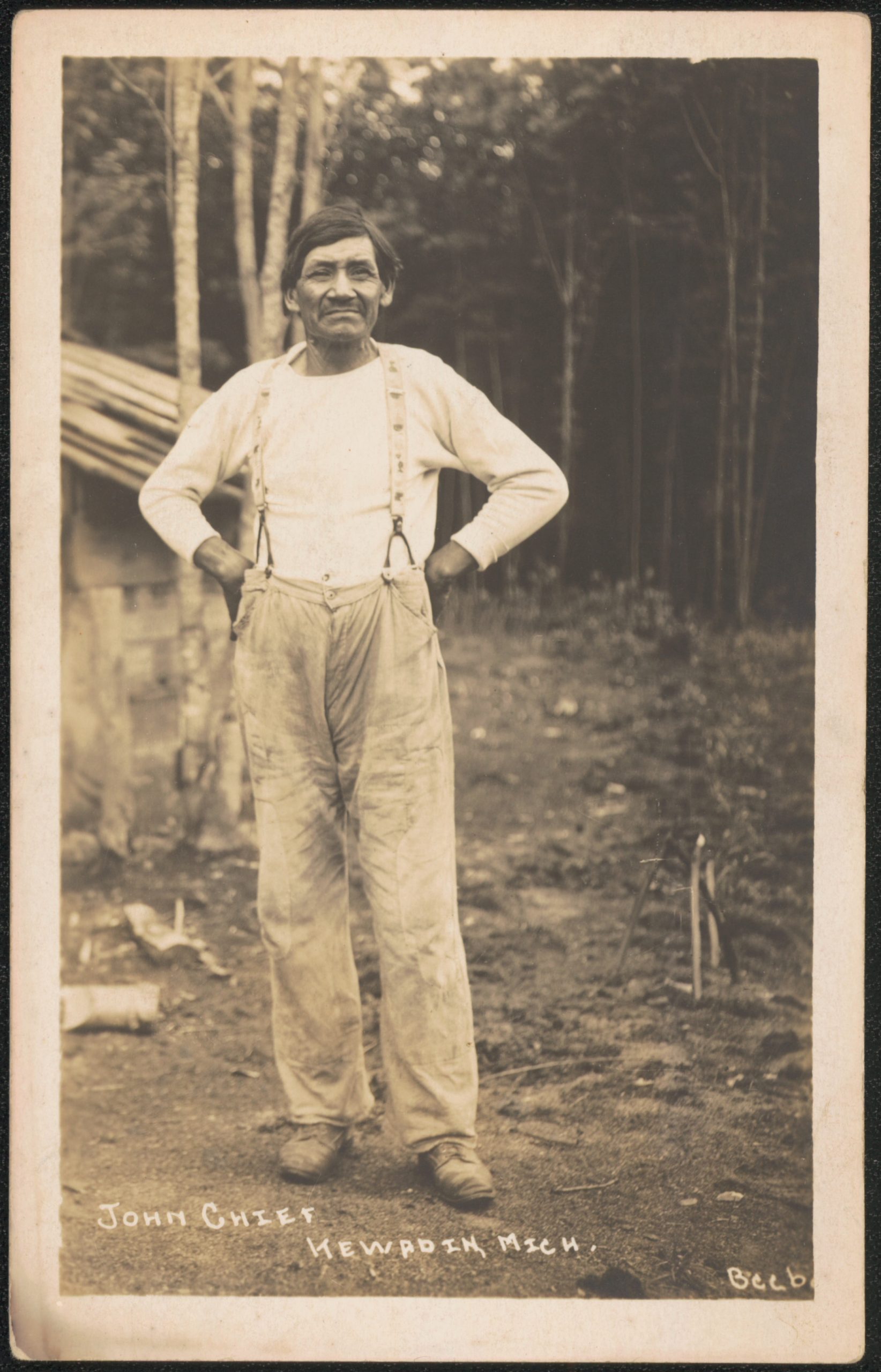

A remarkably different style of photography, photo postcards such as these offer a glimpse into the pride that could accompany private ownership. One photograph features John Chief with his family in front of their home. Each individual brings an object, perhaps of their choosing, to the photographic universe: the child pets a small dog, John holds an unidentifiable tool in each hand, and the woman holds a farming hoe. These photos indicate how some Natives proudly adapted to their new situations and found a satisfaction in photographic representations of ownership.

Residence of John Chief, Kewadin Michigan

Edward L. Beebe

Photo postcard, ca. 1910

David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography

John Chief

Edward L. Beebe

Photo postcard, ca. 1910

David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography

Explore the Exhibit

Select any one of the following options to begin exploring the exhibit, or navigate with the Table of Contents to the left. The sections can be approached in any order.