City Life

No. 56 (Summer/Fall 2022)

An Early North American City

When we think of urbanization in North America, our thoughts generally turn to the cities founded by European colonists in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. We often forget that European adventurers who preceded the colonial settlers encountered the cities of Indigenous inhabitants of North America. Reports and images of these urban sites were published in Europe and constitute some of the earliest descriptions of North American cities.

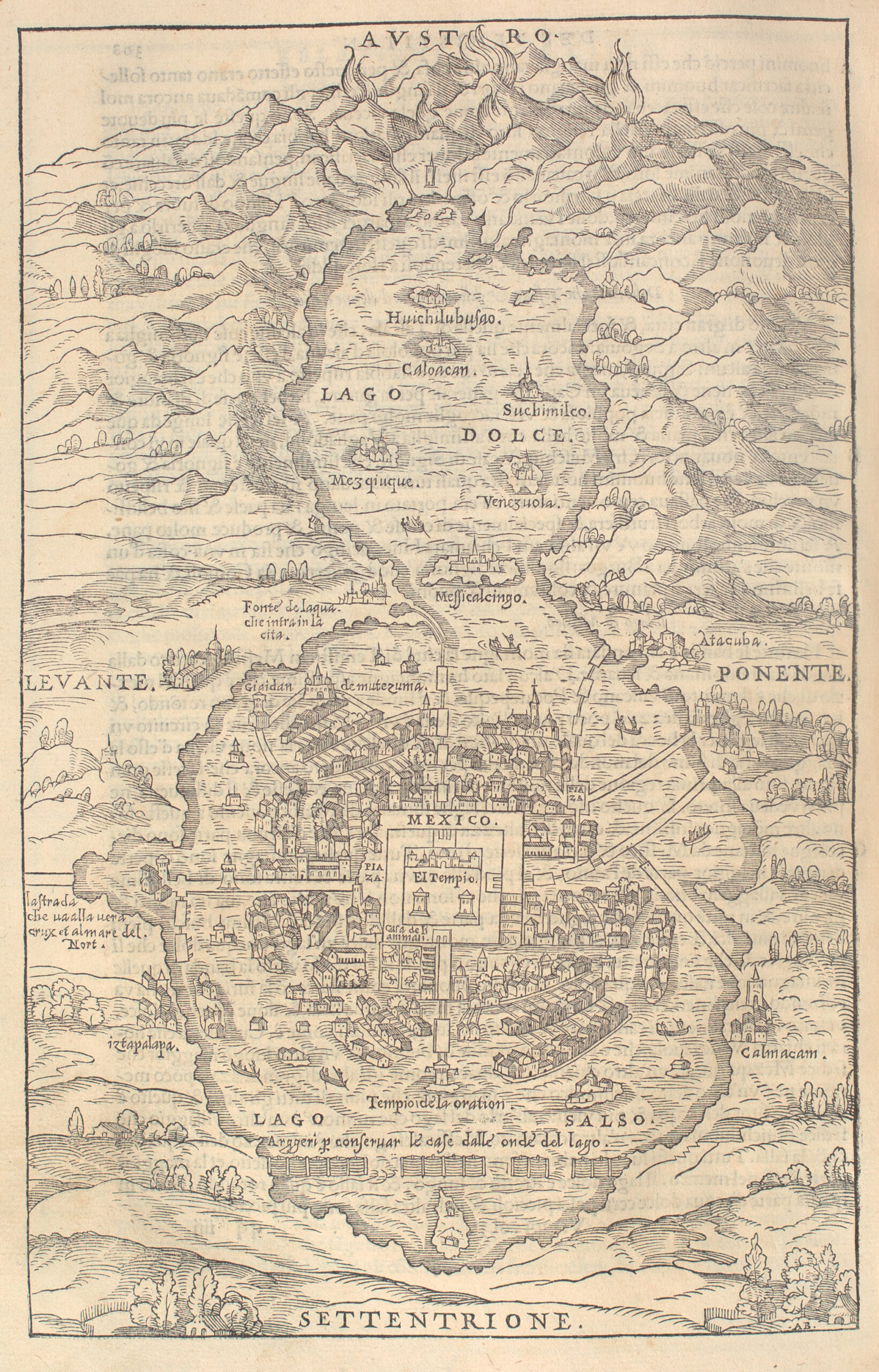

The Clements Library boasts two of these early Native American city plans. The first is the well known woodcut image of Temixitan (i.e., Tenochtitlán, present day Mexico City), published in La Preclara Narratione de Ferdinando Cortese (Venice, 1524) by Hernán Cortés (1485–1547), and also by the Venetian printer, Giovanni Ramusio (1485–1557) in his translation of navigation and voyages of European travelers throughout the world, Delle Navigationi et Viaggi Raccolto (Venice, 1583). The second plan, less well known and also included in Ramusio’s collection, illustrated a translation of Jacques Cartier’s report of his second voyage to North America, to the region of the Saint Lawrence River. Among the many things Cartier (1491–1557) encountered was the Native American town of Hochelaga, near the river and abutting a mountain christened by the French as Mont Royal, later to be known as Montréal. Of the two images of Native American cities, Hochelaga is less well known and deserves a closer look. Not only does it preserve the early history of a city that loomed large in the fur trade, the Seven Years’ War, and the American Revolution, it also symbolized the imposing presence of the Indigenous groups living in a broad area from the mouth of the Saint Lawrence to the Great Lakes.

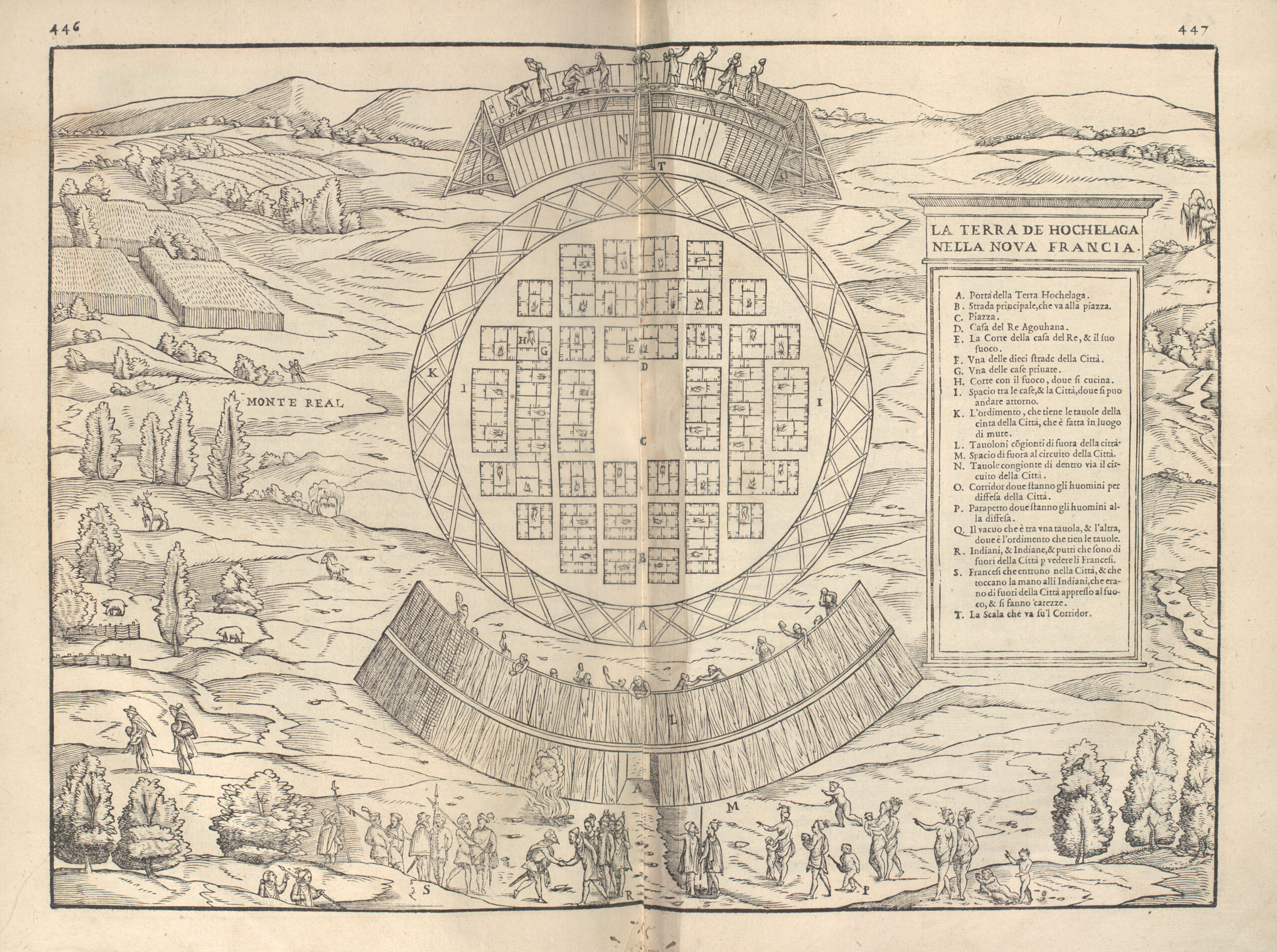

The engraving entitled “La Terra de Hochelaga nella Nova Francia” (The Land of Hochelaga in New France) comprises a plan of the town, with enlarged views of the surrounding fortification, as well as vignettes of the encounter between the residents of Hochelaga and their surprise French visitors. The whole was probably laid out and engraved by Giacomo Gastaldi (ca. 1500-ca. 1565), under Giovanni Ramusio’s supervision.

Cartier, a native of St. Malo in Brittany, France, sailed under the aegis of French King François I (1494–1547) to search for the vaunted Northwest passage to Asia, or, failing that, to find what riches he could in the so-called New World. During his second visit to explore the bay and mouth of the Saint Lawrence River in 1535 and 1536, he and a number of his men traveled up the Saint Lawrence, reaching the site of Hochelaga on the island of what is now Montréal, in October of 1535.

A narrative of this journey was published in Paris in 1545 as Brief Recit, & Succinte Narration, de la Nauigationi Faicte es Ysles de Canada, without illustration. The plan of Hochelaga appearing in Ramusio’s volume includes images that conflate several moments in the narrative into one scene. The text describes the French journey by boat along the Saint Lawrence to Hochelaga where a tumultuous welcome was given by many (Cartier’s narrator says a thousand) men, women, and children, who greeted the strangers with cries of joy and a desire to touch them, followed by gift giving and noisy festivities throughout the night. The next morning Cartier and 25 of his men were led by three residents of Hochelaga through remarkable oak forests along four or five miles of well beaten path to the town, which they found in the midst of ripe grain fields close to a mountain which they named Mont Royal (Monte Real on the Ramusio plan). There, a chief from the town bade them pause to enjoy a fire and more gift giving before entering the town itself. The French remarked on the round layout of the town, surrounded by a wall of wooden pickets in three ranks, two leaned against each other in pyramidal form, and a perpendicular rank that created a defensive platform from which the inhabitants could throw stones to defend the city. Once in the town, they observed the distinct layout of ten streets, regularly arranged around 50 wooden houses, each house having many rooms, a courtyard for a cooking fire, and an attic for storing grain.

Temixitan, from Giovanni Ramusio’s Delle navigation et viaggi . . . (Venice, 1583).

In the town the French were once again greeted warmly and conducted into the central plaza where a fire was lit. Children and women with babes in arms arrived and gathered round to touch the foreigners, while crying with joy and encouraging the Frenchmen to touch their children. After the women and children withdrew, the men of Hochelaga sat down in a circle around the French; some women returned with skins for the French to sit on as they watched the king or grand seigneur of Hochelaga, Agouhana, a man of about 50 years old wearing a large stag skin and wreath of red hedgehog skins, carried in on the shoulders of nine or ten men. He was seated next to Cartier, who observed that the king was afflicted with palsy. Agouhana asked by gesture that Cartier rub his arms and legs. After Cartier obliged, Agouhana gave him his wreath and desired that many of the town’s blind and very old residents be brought into the presence of the French. Cartier recited the “Incipit” (“In the beginning . . .”) from the Gospel of St John, touched the afflicted, and read from the Passion of Jesus, which silenced the crowd, who imitated the gestures of Cartier as he spoke. The French distributed small gifts and tokens to the residents; then Cartier ordered trumpets and other musical instruments to sound, causing further joy. When the French began to return to their boat, some Hochelagans escorted them the short mile to the top of Mont Royal, from which they could see, about 30 leagues around. After learning what they could via signs and gestures of the surrounding countryside and its resources, the French continued toward the river with an escort of Hochelagans, some of whom carried several fatigued Frenchmen on their backs to the boat.

While Cartier’s Brief Recit only gives the French view of the encounter with Hochelaga, it does provide its European reader with a description of a gracious people, warmly joyous in welcome and caring in their sendoff. It can only be imagined what the inhabitants of Hochelaga made of the curiously dressed Frenchmen or what they understood of their unusual language. The fact that the inhabitants of the land of Hochelaga lived in a town reinforces the meaning of “Canada,” the Iroquois- Huron word for “town, village,” the name ultimately applied by Cartier for this region north of the Saint Lawrence. City living was nothing new to these residents.

Abraham Ortelius’ well known atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, (London, 1606) contains this map of the region named La Florida by the Spanish, on which Native American settlements are marked with the city symbol used on European maps.

The image of Hochelaga, like the images of Temixitan / Mexico City, should remind us that “cities” are not the preserve of the European colonist but a phenomenon of human beings living together—satisfying the need for family, shelter, communal access to food, and shared participation in cultural practices such as prayer and story-telling. Cities take many forms as they serve to answer these human needs, and Hochelaga takes its place among them.

— Mary Sponberg Pedley

Assistant Curator of Maps