City Life

No. 56 (Summer/Fall 2022)

Lost In The Crowd

I have always envied people who seem to have a secure sense of direction. Myself, I am easily turned around and once got so lost that I had to casually ask someone the way to “downtown” because I didn’t even know which city I was closest to anymore. In an era before smartphones and Google Maps, it was a completely bewildering experience to be adrift and unmoored in space. Where am I?! It’s a question people had to ask themselves much more frequently in the past than we do today.

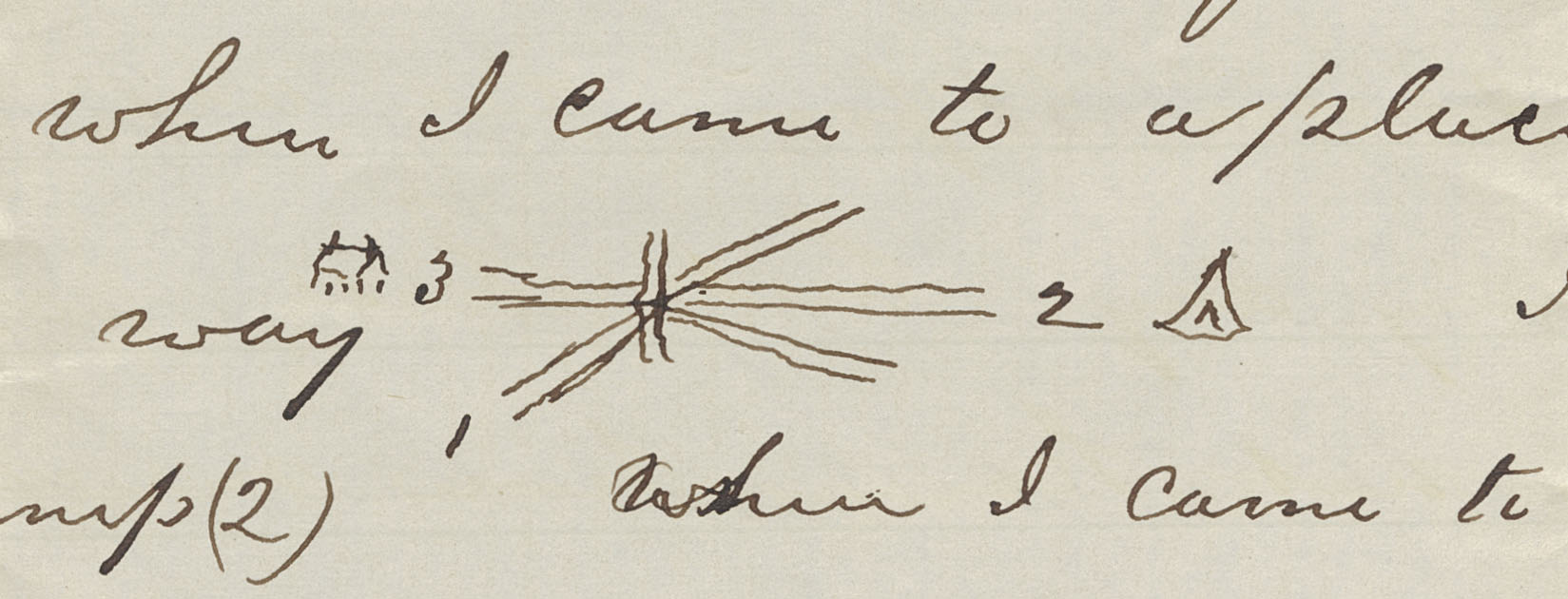

Nineteenth-century travelers writing of their journeys could be quite frank about losing their way. In 1848 George Turley visited Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and wrote home about his arrival. Staying at a “public house” near the steamboat landing, he admitted, “I have not a chance of traveling about the city much, for I get lost so often. I got lost today and went about a mile out of my way.” Living in an age where our phones can readily pull up our exact longitudinal coordinates and our cities are rife with street and traffic signs, it can be easy to forget just how perplexing it might have been to make your way through an unknown space in earlier times. A wrong turn could take up your entire day, and people grew frustrated trying to navigate new cities. Civil War surgeon George T. Stevens wrote to his wife Hattie on January 12, 1862, about one such mishap while he was stationed in Washington, D.C. “I had gone half a mile before I found I was wrong,” he harrumphed, “and when I was at length convinced of my mistake I could not for a long while realize where I was.” He even drew a sketch of where he went wrong, highlighting the offending intersection.

A perplexing intersection in Washington, D.C., got the better of Civil War surgeon George T. Stevens in 1862.

Reading through letters, it certainly seems that getting turned around in cities was a frequent affair. When Julia A. Wilbur went to Alexandria, Virginia, during the Civil War to work with freedmen’s education and relief programs, she wrote extensively back to her colleagues in the Rochester Ladies’ Antislavery Society. In October 1863, she commented on “Grantville,” a quickly growing neighborhood largely populated by freedmen and women. “There are so many houses there now,” she exclaimed, “that I got lost, just as I would in any other city.” More than the organization of streets, access to shops or services, or population density, it was her getting lost that made this evolving space feel urban.

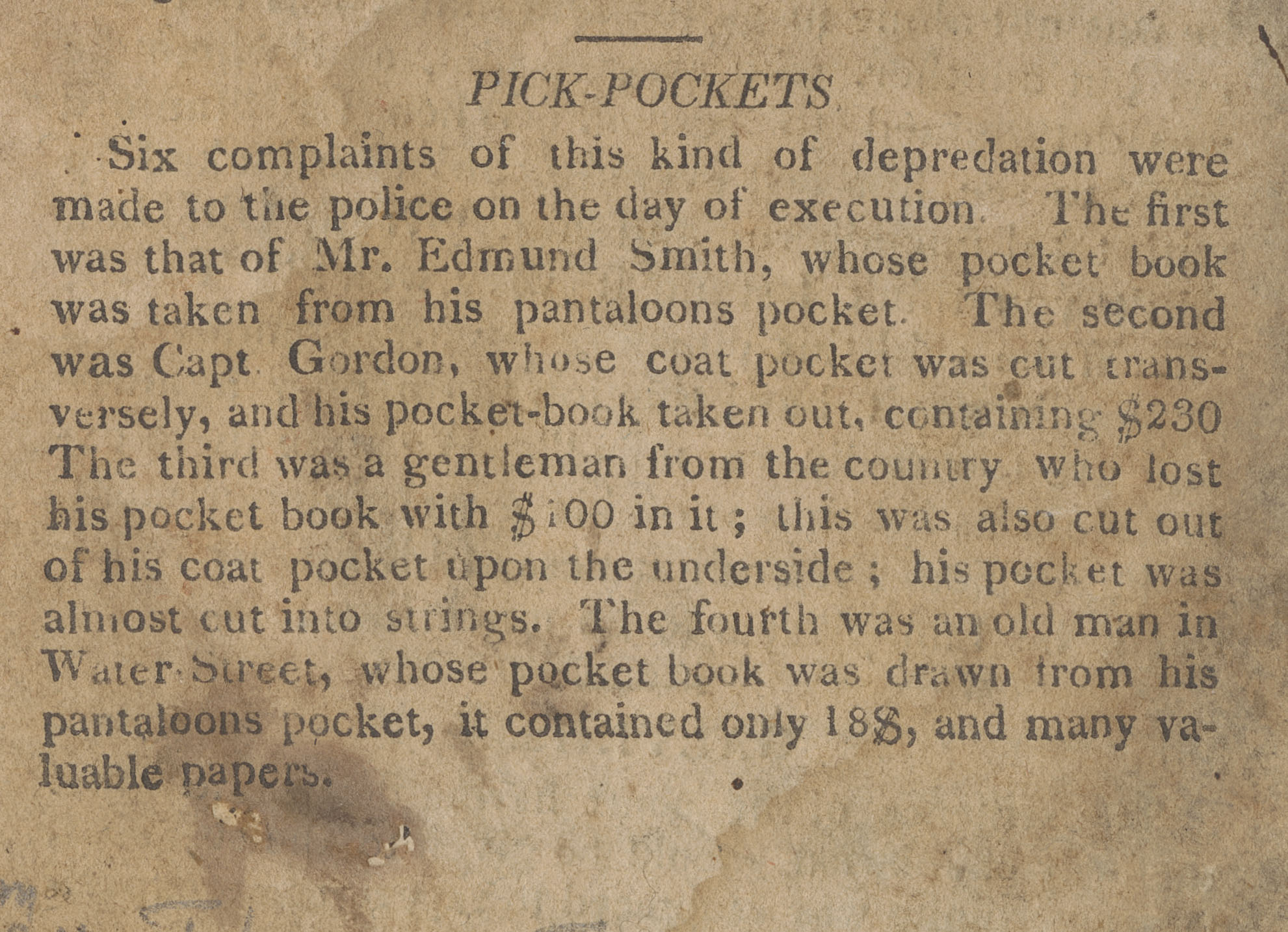

People didn’t just comment on misplacing themselves in the city, but also their belongings. You not only had to keep tabs of where you were, but where your wallet and pocket watch were, too. George Ellington’s The Women of New York, or, The Under-World of the Great City (New York, 1869) laid out just how such things might go missing: “It is a very common and a very old practice for a lady pickpocket to request a gentleman sitting next to her in an omnibus or a car to raise or lower the window. . . . While he is in the act of performing this service, the ‘lady’ relieves him of his watch, and shortly after leaves the stage and is lost in the crowd.” Scanning through 19th-century police reports, notes about petty larceny and pickpocketing pepper the pages. The Clements’ copy of the Buffalo, New York, police docket from 1877 records items stolen from houses, rooms, sleighs, and stores, as well as from right under your nose. George Kearch reported that “there was stolen out of his coat pocket at 700 Washington St about 1030 yesterday AM a 5 Dollar bill.” He suspected two rag pickers, whom he described in great detail, noting their hair, build, clothing, and even the state of their teeth. Whether guilty or just suspected based on social prejudice, there’s no indication the police arrested the two men, suggesting that just like those described in Women of New York, these possible pickpockets melted into the anonymous crowd of the city.

Mingling in crowds meant you had to keep a close eye on your belongings. This warning accompanied an pamphlet about a public execution where pickpockets were hard at work, A True Account of the Confessions, and Contra Confessions of John Johnson (New York, 1824).

Faceless masses concerned 19th-century Americans. In an era of rapid social change and urban growth, the city felt especially unmoored and writers warned of the potential hazards lying in wait. “The Emigrant is released from the social inspection and judgment to which he has been subjected at home,” Charles Loring Brace wrote in The Dangerous Classes of New York and Twenty Years’ Work Among Them (New York, 1872). Luckily for the unsuspecting, he continued, “the machinery for protecting and forwarding the newly-arrived immigrants, so that they may escape the dangers and temptations of the city, has been much improved.” Cities would ensnare the unsuspecting, lead astray the desperate, or offer up opportunities for ne’er-do-wells, such books suggested. While sensational printed accounts of crime or poverty underscored broad anxieties about how society functioned in cities, everyday people worried about loved ones moving there on a smaller, more human scale. “On the 7th of Nov. 1863 I parted with my youngest son Henry, a lad 19 years old to go to a greate city and battle the temtations that will be placed before him,” Royal Danforth of Raynham, Massachusetts, fretted in a letter from the Duane Norman Diedrich Collection. “When I think of him and compare his case with others that have fallen, I tremble for his safety.” You could not just get lost physically in the sprawling city, but morally, too.

The orderly scene portrayed in this 1856 lithograph of Broadway by Julius Bien likely masks what was a confusing whirl of activity happening at street level.

But when you don’t want to be found, getting lost can be a blessing. In his autobiographical recounting of his escape from enslavement, Frederick Douglass remarked, “the chances of success are tenfold greater from the city than from the country.” Having access to transportation options, mingling in crowds, and being in a place where your social connections were more diffuse, could mean you might find an opportunity to slip away. Even those living in freedom could use the city as a protective cloak. In 1813 James Craig was searching for Sophia Elizabeth Feranze, a mixed-race woman living in Philadelphia who owed him money. As he reports in a May 29, 1813, letter in the African American History Collection, he thought her “slippery as an eel,” and despite his efforts to lean on his contacts he could not “obtain any other information than she lives with a Monsr. Longue, or Largee a french man . . . this is all I can learn about her.” Amidst the ebb and flow of residents, visitors, merchants, or sailors, people who did not wish to be found could try to lose themselves and with any luck maybe make themselves anew.

The excitement of an arriving ship increased the chaos of navigating urban streets, depicted by Edward Jump’s STEAMER DAY IN SAN FRANCISCO, (San Francisco, 1866).

Our cities have grown exponentially over the centuries. Looking at maps, the boundaries through the years expand outward, buildings grow upward, populations boom. But even in the 19th century, cities were disorienting places. While sanitized birds’-eye views tend to paint a rather orderly picture of tidy streets, the truth was often much messier, louder, and crowded. In the hubbub and whirl, you could lose yourself—in a good way, as no one knew you and you could engross yourself in the culture and forget yourself for a while. But the loss could be hard, too—a wrong turn, a stolen wallet, an overindulgence. The experience of getting lost, in its many forms, was entwined deeply with the experience of the city itself. And it makes you wonder, just a bit, in this age with a phone in our pocket whispering which way to turn, what we might lose when we can no longer get lost.

— Jayne Ptolemy

Assistant Curator of Manuscripts