City Life

No. 56 (Summer/Fall 2022)

Urban Panorama

Artists have long striven to replicate visual perception and wrestled with the limits of various image production methods. One of the great historical challenges has been that paintings and photographs are static, while our actual perceptions unfold in time and space. Our eyes and heads are constantly moving from side to side and up and down. Scrolling painted panoramas—such as the Gettysburg Cyclorama (a cylindrical painting of the battle that opened to great acclaim in the 1880s) and table-top toys such as the zoetrope—were visual attempts to represent time and space in the 19th century. The first photographs that appeared before the public were dazzling in their detail. Early reactions to daguerreotypes described them as “frozen mirrors,” commenting on the amazingly fine qualities but also hinting at the inadequacy of the static and narrow field of view. An image from a box camera aimed in a single direction, however vivid in detail, does not represent the human experience of side to side vision as we move through space. Photographers were well aware of this—after all, Daguerre was also a painter of panoramas. Many took steps to better represent an active visual experience with their photographs, and the complexity and human activity of urban environments was a particularly tempting subject.

In the earliest attempts at wide-scale photographs, ambitious daguerreians framed multiple plates side by side to represent a wider field of vision. The 1848 panoramic view of Cincinnati by photographers Charles Fontayne and William S. Porter, now at the Cincinnati Public Library, took eight plates to capture a two-mile span of the riverfront. With the advent of paper photography, a series of prints could be pasted together to make a single sweeping panorama. These came close to replicating what we see as we shift our vision from side to side, but were still broken into segments. Achieving a uniform exposure and hiding the seams was a technical challenge for even the most skilled practitioner.

Flexible roll film began to replace glass and metal plates in the late 19th century and made it possible for a camera to have a curved film holder that maintained a constant focal distance for a very long piece of film. Add a lens that swivels from side to side and the true panoramic camera was born. The first mass-produced American panoramic camera, the Al-Vista, was introduced in 1898. Perhaps the most often used panoramic film camera was the Cirkut camera, patented in 1904. It used large format film, ranging in width from 5″ to 16″ and was capable of producing a 360-degree photograph measuring up to 20 feet long. For the most part, this equipment was used by professional photographers—the cameras were expensive and required unusual darkroom setups for printing the enormous negatives. But amazing things were now possible, such as seamless panoramic views of cities and photographs of very large groups of people.

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers paused during the Detroit Labor Day parade of 1916. Each member held a staff with an electric bell on the top end, which appears to be wired to a controller on the lead vehicle. The bells were likely tuned to differing pitches, making this a walking musical instrument, suitable for a panoramic camera portrait. From the David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, the majority portion donated by David B. Walters in honor of Harold L. Walters, UM class of 1947 and Marilyn S. Walters, UM class of 1950.

One of the obvious effects of panoramic photos in urban environments is that the straight lines of the man-made world appear curved and the perspective looks distorted in ways that don’t seem to match the way we understand our world. Although it looks wrong when viewed as a flat print, these images are in fact similar to the images received by our spherical eyes. What our brain “sees” is processed with other knowledge about the shapes and spaces around us so that we understand that the walls, although perceived in a spherical way, are in fact straight and vertical. The panoramic camera delivers just the image, stripped of any back-end mental processing, and so appears “wrong.”

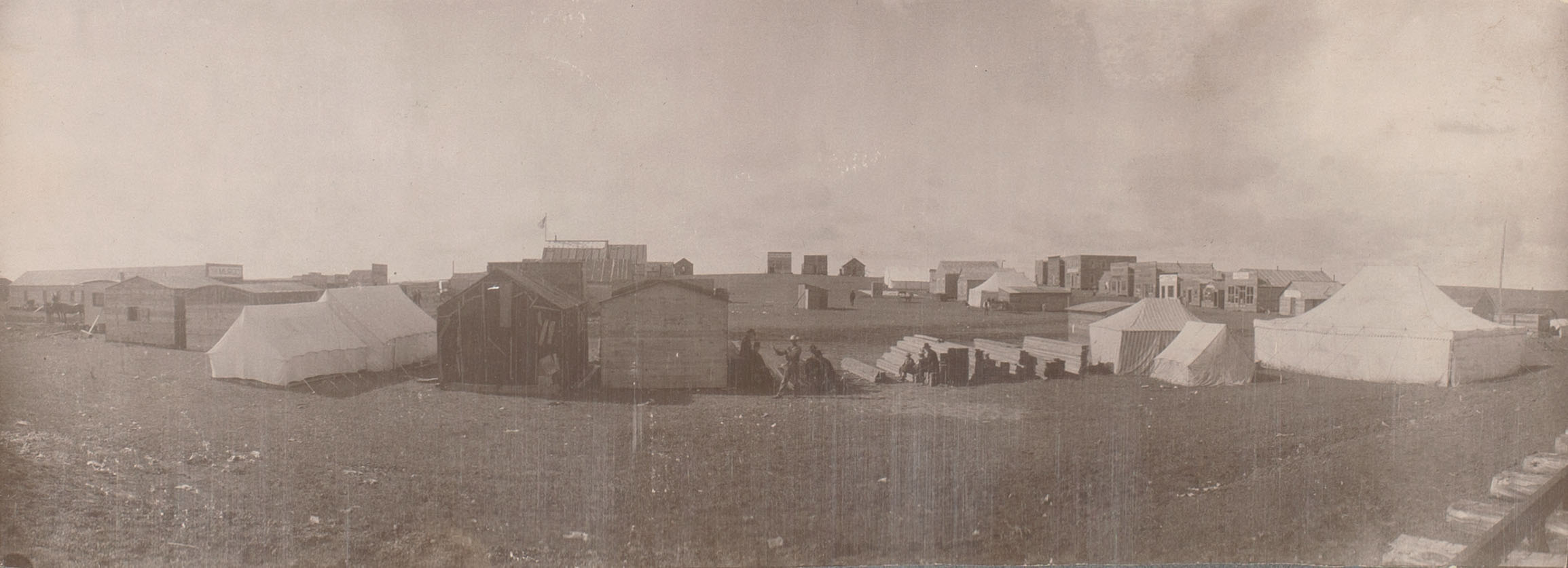

Among the scarce examples of amateur panoramic photography is this view of the emerging railroad town of Murdo, South Dakota, circa 1906. The town is named for Murdo McKenzie, a Texas rancher who drove masses of longhorn steers north to graze on the grasslands of Standing Rock Reservation of the Lakota and Dakota tribes. Other images from this album suggest that the photographer was the daughter of E.L. Morse of Chamberlain, South Dakota, who owned a dray and teamster business. The temporary shelters and recently unloaded stacks of lumber near the railroad tracks give the impression of a newly born town. The sweep of the panoramic camera expands the sense of endless grasslands. This may be the earliest image of the town of Murdo.

We are now in an era whereby we experience our surroundings through digital screens. Taking a panoramic photograph is now quite common as most digital cameras and phones provide this feature. Absent production costs, a digital camera can be a toy for visual experimentation. Digital panoramas of tall buildings taken vertically, and images made while walking or from a moving vehicle, present astonishingly original perspectives. Cities are subjects of such scale and complexity that to this day we are evolving new ways to view and understand them, and photographic panoramas continue to inform how we perceive and record our urban environment.

—Clayton Lewis

Curator of Graphics Materials

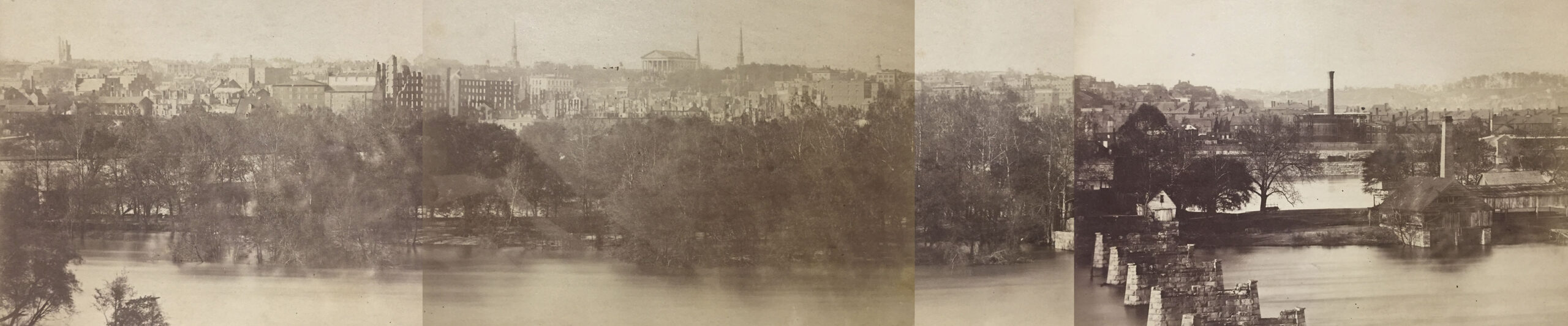

The devastation after the fall of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, in April of 1865 attracted photographers from across the country. This composite of nine eight-by-ten inch prints from glass plates by an unknown photographer is the earliest photographic panorama in the Clements collection. Numerous photographers took essentially the same photos from this same location within days of each other, making them nearly impossible to distinguish.

Encompassing 180 degrees, this viewof Campus Martius by The Hughes & Lyday Co. shows Detroit’s old City Hall and the Majestic Building along Woodward Avenue at Cadillac Square, probably taken in the early morning, using a camera with a pivoting lens. A slight dusting of snow covers the ground, except where streetcar traffic has swept it away. Most of the buildings pictured were demolished in the 1960s, but the 1867 Soldiers and Sailors Monument remains. Donated by Doug Aikenhead.

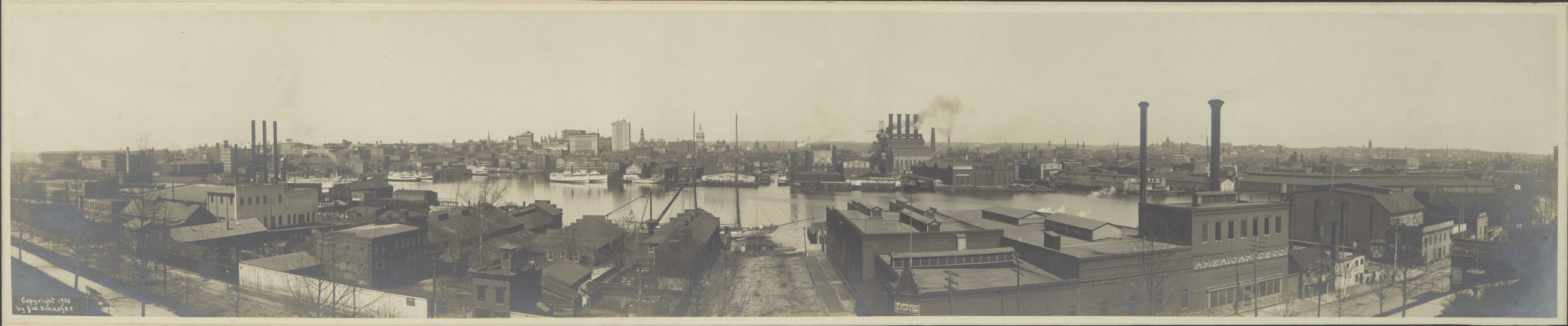

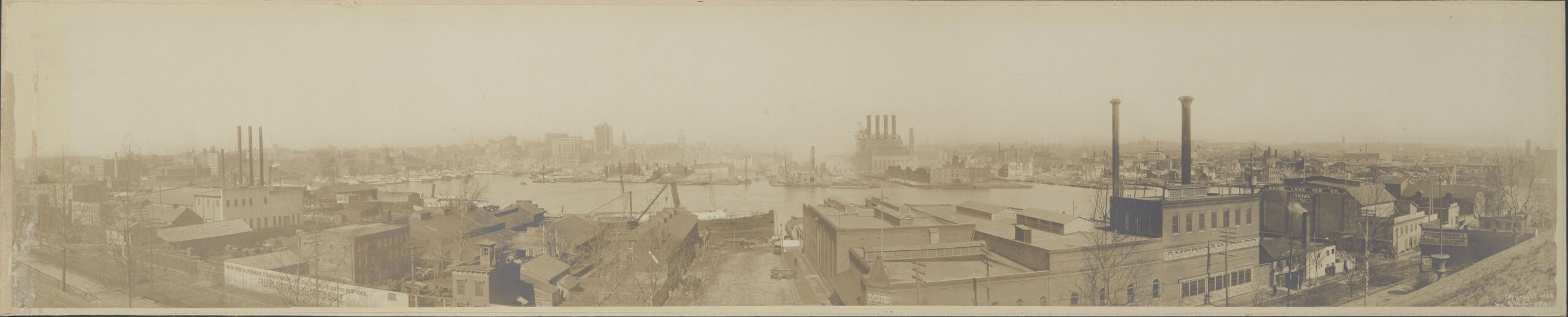

Among the very worst fires in American history was the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 that overwhelmed local firefighters and destroyed much of central Baltimore. Supporting equipment arriving from other cities was unable to be used due to inconsistent and varied hose sizes. This debacle led to federal laws standardizing fire hydrants and hoses. These two views were taken by G.W. Shaefer from the same location on Federal Hill overlooking the Inner Harbor before and shortly after the fire. Among the harbor-side industries on the near side is American Ice Company which supplied the fishing fleet with ice for preserving the fresh catch.

Thomas Sparrow was an Ohio photographer who specialized in panoramas of very large groups. A great deal of time went into the setup of this scene in front of the Saint John’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in Cleveland on May 2, 1915. The front steps were not large enough to hold the full congregation. The risers were assembled across the sidewalk in a measured arc so that the distance to the camera would be equal. Getting everyone in place and holding still for the time it took to make adjustments challenged the patience of all, no doubt. The result is a fantastic community portrait. Well done, Mr. Sparrow!