A Profound and Enduring Impression

According to Welsh legend, a royal prince by the name of Madoc supposedly took to the high seas and departed from Wales for new pastures in 1170 after the death of his father led to a bloody power struggle. The tale of Madoc, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, evolved to incorporate the idea that he had actually navigated his way to America and established Welsh colonies, thus conveniently providing a British presence in the New World that predated any and all Spanish claims. In all likelihood, Elizabeth I and her advisors initially deployed the Madoc story strictly as propaganda in order to trump their Spanish rivals. However, the modified Madoc legend ended up taking on a life of its own, especially amongst Welshmen and Welsh-Americans who were exceedingly proud that one of their own might have been the true “discoverer” of the New World.

Over the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, countless rumors were circulated regarding the existence of so-called “Welsh Indians,” descendants of Madoc’s colonists who were believed to have mixed with local Native populations and yet still clung to vestiges of Christian traditions, established fortified European-style towns, and spoke the Welsh language fluently. At first, attention focused on tribes of the Eastern seaboard near locations where Madoc’s colonists were thought to have landed, such as Newfoundland, New England, the Carolinas, and Florida. In John William’s Farther Observations on the Discovery of America, by Prince Madog ab Owen Gwynedd (1791), the famous accounts of Reverend Morgan Jones and Captain Isaac Stewart feature prominently. Jones had claimed to have been captured in 1660 by Indians in Tuscarora country while visiting South Carolina. His imminent execution was prevented only after the Indians heard him praying in the Welsh tongue, which they miraculously understood. Stewart likewise claimed that he was captured around 1766 before being rescued by a Spaniard and a Welshman named John David. During their subsequent adventures, the company crossed “the Mississipi near Rouge or Red River, up which we travelled 700 Miles, when we came to a Nation of Indians remarkably White, and whose Hair was of a reddish Colour.” John David was reportedly astounded to find that these people were also able to speak Welsh.

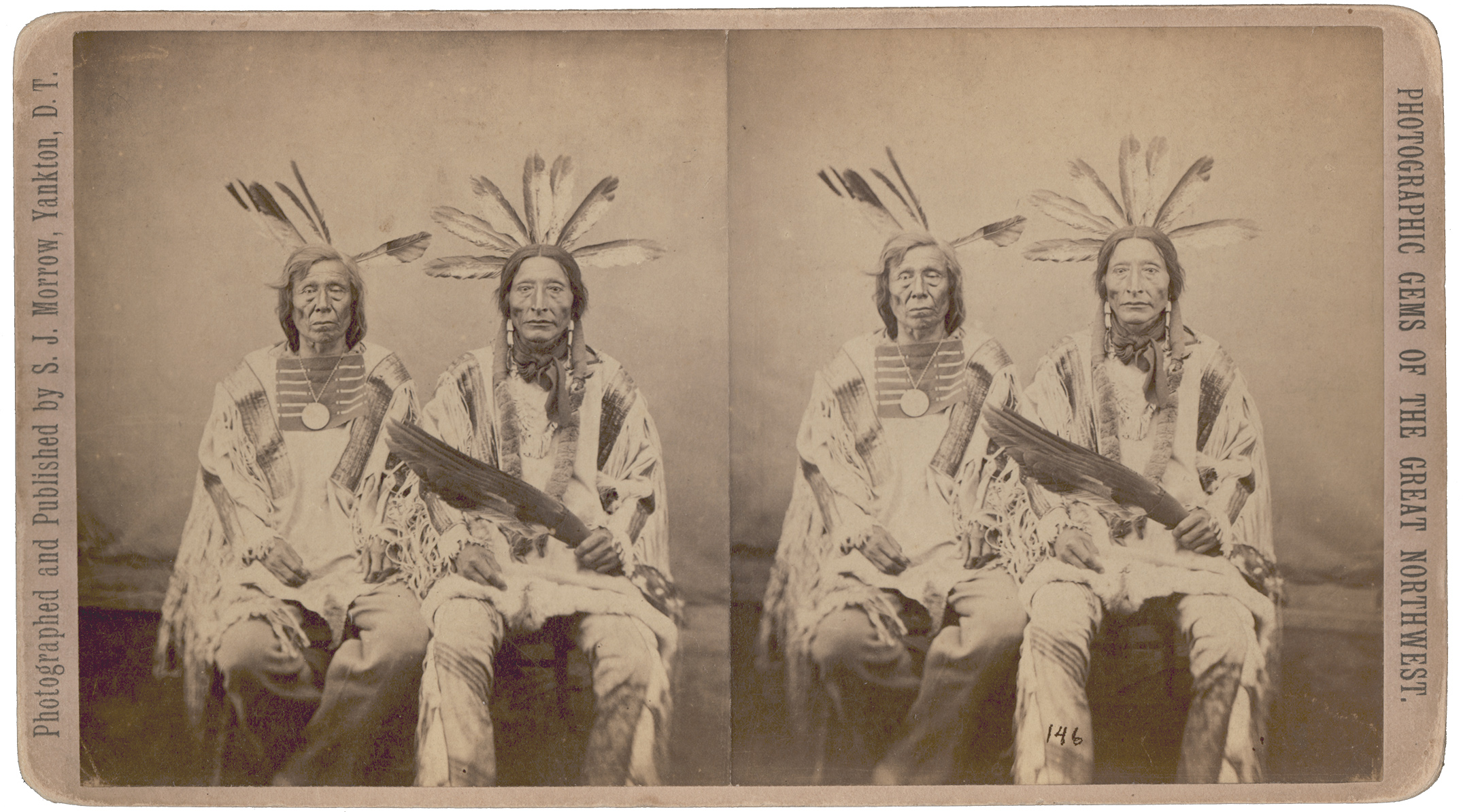

Photographer Stanley J. Morrow (1943-1921), active in the Dakota Territory region during the late 1860s and 1870s, alluded to the Welsh-Mandan theory in a caption on the back of this image, which reads, “1st and 2nd Chiefs of the Mandans, descendants of a colony of Welch.” This caption indicates that enough people were familiar with this idea to warrant Morrow using it as a marketing point.

Reverend Bowen also referenced a letter published in the Kentucky Palladium in 1804 by a Mississippi judge, which stated that “No circumstance relating to the history of the Western country probably has excited, at different times, more general attention and anxious curiosity than the opinion that a nation of white men speaking the Welsh language reside high up the Missouri.” In fact, many early explorers of the American West, such as Lewis and Clark (who were instructed by Thomas Jefferson, himself of partial Welsh descent, to be on the lookout for Welsh Indians), considered the discovery of Madoc’s descendants a bonus subplot of their missions.

The works produced by Swiss-French artist Karl Bodmer (1809-1893) during the Weid Expedition of the early 1830s are considered to be some of the most important and accurate visual depictions of indigenous peoples and natural landscapes from the early days of exploration in the American West. In this detail of a rendering of a Mandan settlement called “Mih-Tutta-Hangkusch,” villagers can be seen operating the fishing boats that George Catlin and others so strongly believed to be derived from the Welsh coracle.

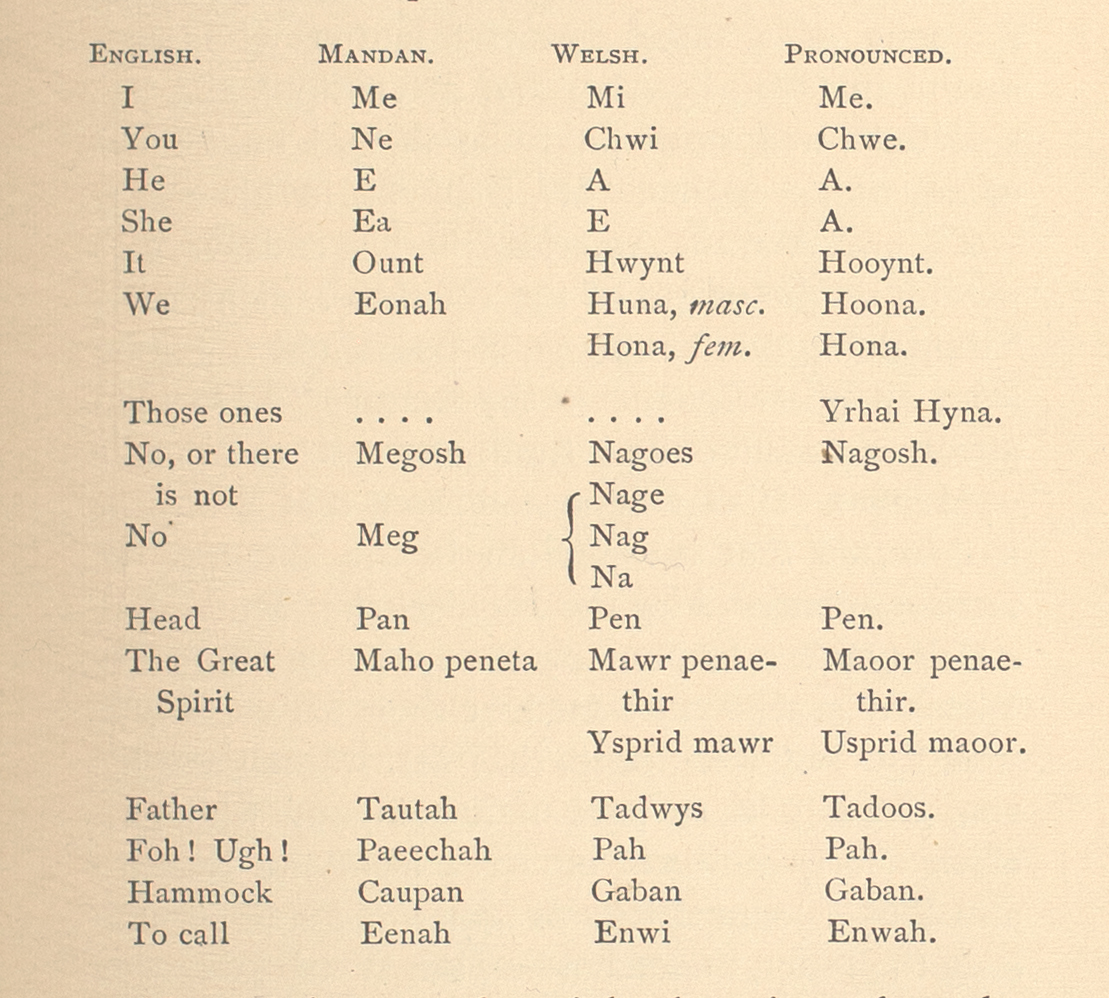

Needless to say, all theories regarding the existence of Indian tribes descended from a renegade 12th-century Welsh prince have long proven to be false. English skeptic Thomas Stephens vigorously disputed many of the popular narratives of his day and age that were associated with Madoc and the Welsh Indians in his Madoc; An Essay on the Discovery of America by Madoc ab Owen Gwynedd in the Twelfth Century (1893). Reverend Morgan Jones’ captivity story was shown likely to be nothing more than an elaborate hoax, while Catlin’s comparative linguistic analysis of Welsh and Mandan was demonstrated to be a laughable misrepresentation of the facts. However, Stephens found his efforts at undermining the Madoc legend’s legitimacy surprisingly difficult, particularly with regards to individuals of Welsh extraction who continued to defend it. According to Stephens, “The tales told respecting the Welsh Indians found favour with many persons . . . but in Wales itself they produced a profound and enduring impression.”

Comparative analyses of Mandan and Welsh words with supposedly similar phonetics and meanings, such as this table included in Bowen’s America Discovered by the Welsh, were considered by Catlin and others to be irrefutable evidence of the tribe’s Welsh heritage.

—Jakob Dopp

Cataloger, Graphics Division