Golden Dreams, Waking Realities

One such dreamer, Alexander Parker Crittenden, hailed from a beleaguered family in Kentucky. As he worked to extract his widowed mother from debt in 1837, he fell hard for the strong-willed Clara Churchill Jones. The Clements Library’s Crittenden Family Papers document their early courtship, when he wrote frequently to Clara, cross-hatching his letters to double the amount of starry-eyed remembrances he could fit into one mailing. “You must, indeed you must,” he implored, “keep that wandering spirit of yours at rest, else I shall be forced to find some charm to quiet it. A kiss every night would be effectual, but how is this to be accomplished when there is such a distance between us. There is but one course ̶ to appeal to yourself not to appear to me in my dreams. ’Tis such a disappointment when awakening to find it all but a dream.” A young man of 21, Alexander found his mind occupied with love and desperate attempts to secure his financial footing to assure the Churchill family that he could support a wife. His dreams for the future were entangled with his dreams of Clara. He sheepishly admitted that in his pursuit of success, “I must lead an unsettled life, and in all probability soon be compelled to go south or West.”

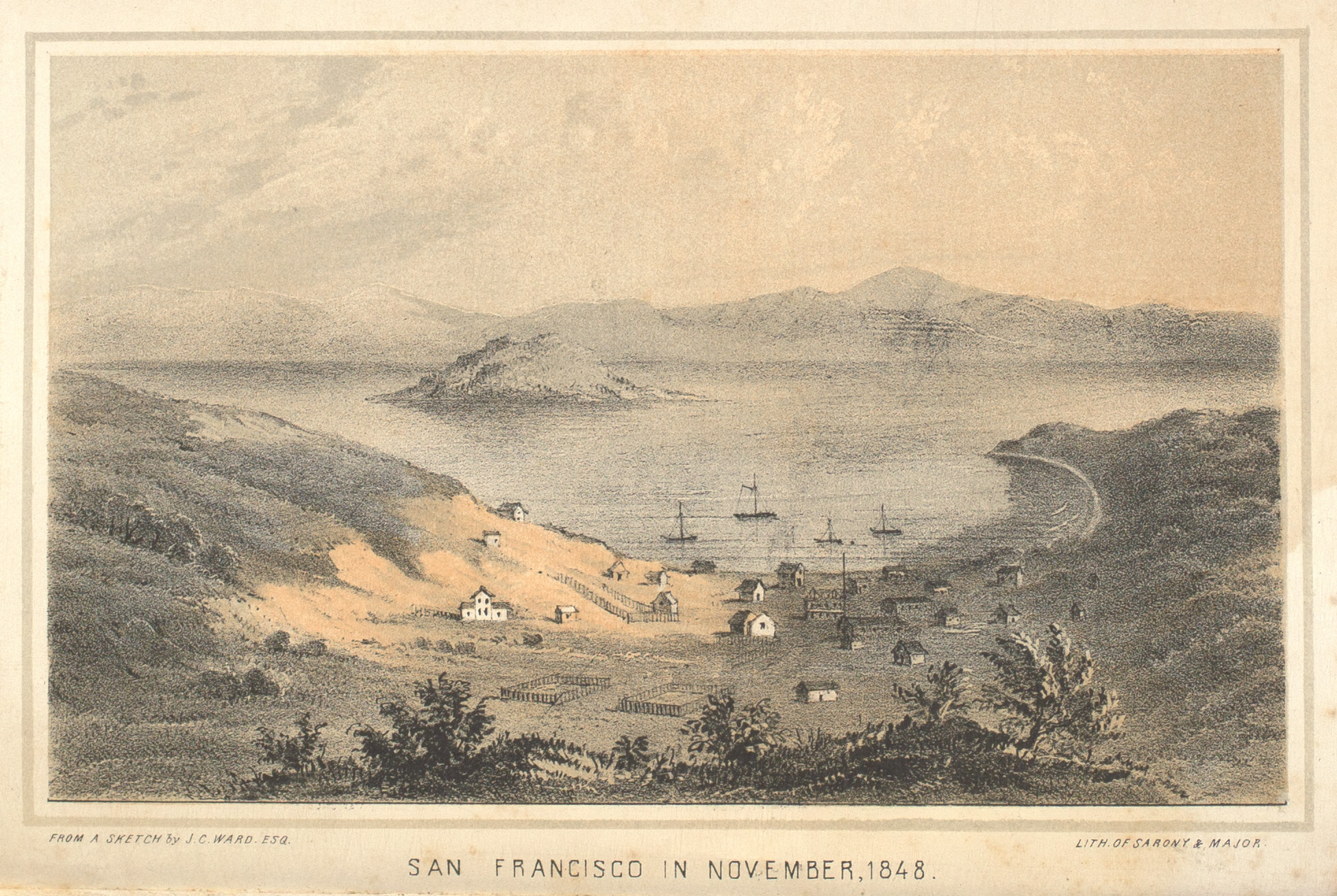

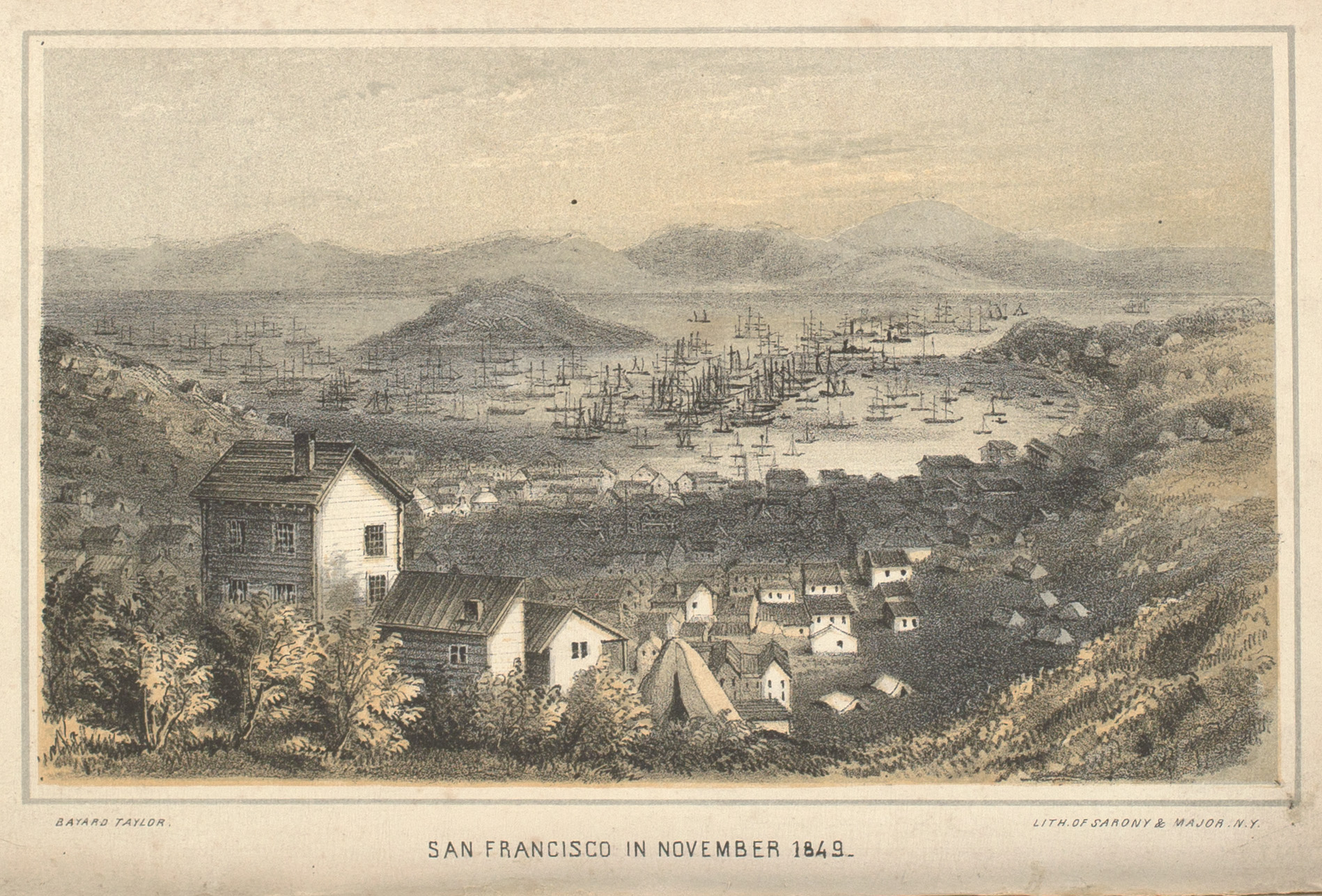

Californian cities grew at a bewildering pace. Bayard Taylor, sent by Horace Greeley of the New-York Tribune to report on the Gold Rush, noted in his book Eldorado (1850) that “People who have been absent six weeks came back and could scarcely recognize the place.”

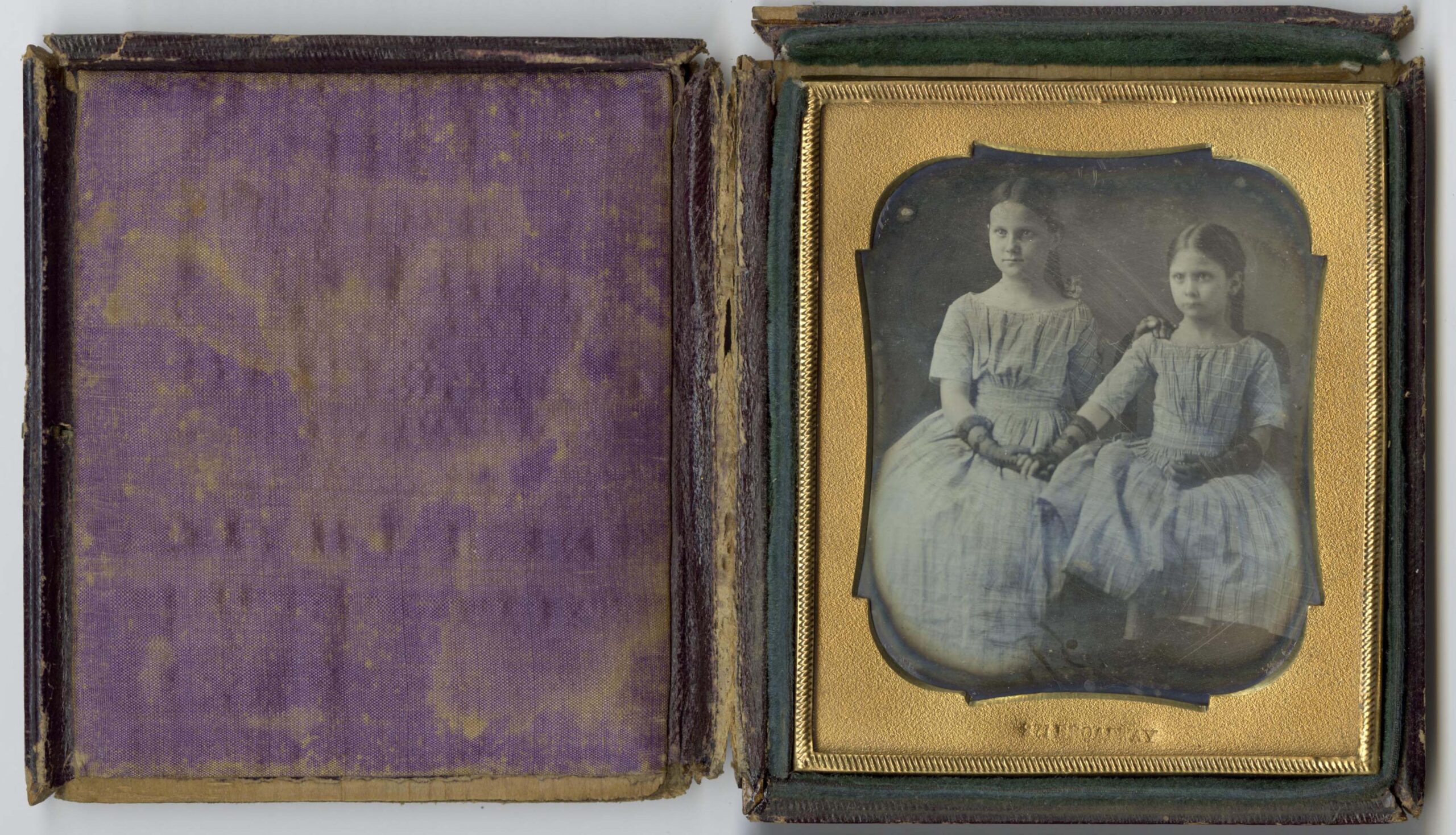

Human connection was closely prized by those in the western city. When a great fire rushed through San Francisco in May 1851, Alexander described how he went about trying to save his possessions. “I had not much to lose,” he admitted. “The most highly prized of all my goods & chattels were your portraits. They were the first things I thought of. I did not know how to secure them. I tried to put them in my pockets ̶ but reflecting that they would be injured, perhaps destroyed by the fire and water to which I must be exposed ̶ I concluded that the trunk was the safest place for them until the moment came when we should be compelled to retreat.” Surrounded by a city engulfed in flame, “a perfect sea of fire roaring and rushing around us with a sound louder than the breaking of the waves on the shore,” Crittenden held on tightest to the daguerreotypes of his family, his connection to those he left behind as he chased visions of success. He was thoughtful about sending Clara pictures of himself as well. One he sent in October 1850 after his plans to visit her were dashed once again by a financial setback, “a blow almost too heavy to bear.” “If I cannot come in person I will send my image. It is the best I can do, but it is a poor substitute. It is deficient in the warm heart beating only for you. It cannot open its lips and tell you how dearly you are loved.” Alexander’s dreams had shifted from earning a great fortune to finding a way to be together again. “I wish we could live upon affection and that that most hateful of all words ̶ money ̶ might never be mentioned again.”

This photograph of Alexander’s eldest daughters Laura and Nannie Crittenden was likely taken sometime around 1851, posing the alluring possibility that it could have been one of the daguerreotypes he guarded so carefully during his early years in San Francisco.

In 1851 British sailor William Shaw published Golden Dreams and Waking Realities: Being the Adventures of a Gold-Seeker in California and the Pacific Islands. Lured by the promise of Californian wealth, Shaw set out for the mines. After a grueling attempt, he abandoned the dream, packing his belongings to seek better prospects. “The wind was blowing hard and the rain pelted heavily down, as giving a last long look at the diggings, I thought of the golden dreams and buoyant hopes which had lured us to them; and turned my back upon a spot where these had been so rudely dispelled by the waking realities of privation and suffering.” Many fortune-seekers were drawn to the promise of California by stories of successful mines, of gold dust blowing in the streets, of cities erupting into being and bustling with newcomers and opportunities. But mining proved difficult, unsteady work, requiring far more financing and luck than most had. And even those who were drawn to the coast not by gold but by the attendant boom it brought to the region, found that life in the new West could be risky. The speculative frenzy that undergirded San Francisco’s growth could tumble even the most optimistic of men. Alexander Crittenden struggled alongside them. Working for years to secure a strong enough footing to bring his family with him to California, his dreams of financial freedom waned in the face of homesickness and separation. And in turn, when his family was reunited, happiness again failed to follow. Love and stability, like his dreams of fortune, were always a step or two ahead of him. San Francisco may have sprouted from Americans’ dreams, but that doesn’t mean they always came true.

—Jayne Ptolemy

Assistant Curator of Manuscripts