Harriet Wood Townshend

Related Resources

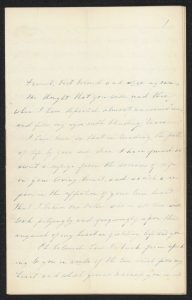

“Should you connect yourself again, love, by that sweetest of human ties, guard well the object of your choice from the more than ordinary trials of a stepmother, let her not be ignorant of the prejudice she must encounter, and which I fear must embitter the life of a senstive woman…”

–Harriet Wood Townshend, letter to Norton Strange Townshend of 1854

Norton Townshend’s first wife, Harriet Newell Wood, was born February 4, 1826, in Chester, Massachusetts, the daughter James Wood, a farmer and wool merchant, and his wife Mary Smith. After traveling through Ohio’s Western Reserve on business, James moved the family to Lorain County, Ohio in 1833. He was attracted by quality of the farm land as well as a blossoming religious movement in the town of Oberlin, whose members advocated charitable acts, education, and plain food and dress.

Despite their sympathy with the Oberlin movement, the Woods “did not feel called to go to the full lengths” of its members; according to family tradition, “the practical Yankee in [Mary Wood] failed to see how her personal holiness could be promoted by wearing an ill-fitting gown, especially as her clothing was the testimonial of her own skill and taste in dressmaking.”1 However, the movement’s basic values of earnest and intense religious devotion, liberal education for all, and opposition to slavery seem to have been important to the family. Harriet was raised this reform-minded environment on her parents’ farm. In 1843, she married a family friend, Norton S. Townshend, at the age of 17. The couple had three children: Arthur (born 1844), James (1846), and Mary (1849). Arthur died of a respiratory illness at the age of four, but James and Mary lived to maturity.

Harriet’s sensitive but humorous perspective can be observed in her correspondence; the majority of what survives was written to her sister, Sara Wood Keffer and covers the last years of her life, in the early 1850s. Her letters describe many aspects of daily life, including housework, clothing, visits with friends, her religious thoughts, and her sadness at the frequent deaths of her neighbors. Some of the most fascinating describe her visits to Washington, D.C. where her husband was a Congressman between 1851 and 1853. Picking up on Salmon P. Chase’s characteristic intensity, she wrote, “Mr. Chase has just come into our room and it looks like fury but as he is nearsighted I will not afflict myself too much about it.” She also describes a visit to the “Free Church” in Washington, where she and her husband sat among a “thin” crowd consisting of Chase, Joshua Giddings, and Gamaliel Bailey and listened to a sermon “replete with antislavery sentiments.”2

Upon visiting Mount Vernon in 1852, she shared a humorous story with Sara:

“I forgot to tell you a distinguishing honor I had the other day at Mount Vernon. I went into Gen. Washington’s privy, the one, no doubt, he has often graced by his presence, in company with Mr. Durham of Wisconsin and a gentleman from Milwaukee. We took it for a summer house, I may well add, lest you should think my morals have been affected by southern freedom of manners. I who was leading the way to the summer house with great enthusiasm, rushed out through the bushes at the side and almost died with laughter and mortification. That is one of the things about Mt. Vernon that I shall never forget, a most romantic association. The Dr. was perfectly convulsed when I told him. Is not this a queer thing to write about?”3

Interspersed with anecdotes like this are Harriet’s thoughts on religion and mortality, made more poignant by the proximity of her early death. Many of the Woods proved tragically susceptible to tuberculosis: the disease took the life of Mary Wood, Harriet’s mother in 1841, Harriet’s 5-year old son Arthur in 1849, and her son James at the age of 42 in 1888. Harriet contracted tuberculosis around 1850 or 1851 and lived in a weakened state for several years. Before her death on January 28, 1854, she wrote an extraordinarily moving letter to her husband, mourning the end of their time together:

“Dearest, I have lived over all the anguish before you, the vacant home, the solitary pillow, the care of your motherless children, the numberless trials and inconveniences which will make your life grievous, all I know and have felt till my whole being has gone out to you in inexpressible tenderness. The longing to comfort you when I am no more is so intense that I feel, I know, it must be an inextinguishable part of my being which shall have its scope and exercise in the life that is to be.”

On the topic of what she considers Townshend’s inevitable remarriage, she writes:

“Let her be, darling, a woman of piety and of prayer, who will make the moral and spiritual training of our dear ones her first care. I have too much confidence in you to believe that you would be influenced unduly by personal attractions in so momentous a matter. There will be more involved in this than in your first choice. Joined to the craving want within of companionship and wifely affection, is the cry of young children for a mother, and that place none but a true woman can fill.”

Toward the end of the letter, which Harriet wrote in several installments over a period of a few weeks, she pleads with him to be actively involved in the children’s lives:

“And, oh my husband, never, never relinquish the charge of them to another as you have to their own mother, they are all that remains to you of me, regard them as a sacred trust I have left in your keeping. Open your heart to the influence of their childish sayings, draw out their little, crude thoughts & establish between them and yourself the closest intimacy. Though it take hours time that you can ill spare, you will be amply paid for your task of love and self-denial.”4

Perhaps there is even a hint of reprove for previous detachment from child-rearing duties in this statement. In any case, in Harriet’s acceptance of the idea of a stepmother for the children as well as her carefully considered instructions for her husband, she demonstrates a startling maturity and thoughtful acceptance of her own death. Although her life ended at just 27 years old, her influence must have been felt for far longer.

|

1 “The Woods and Townshends in Avon/My Life” 2 Harriet Townshend letter, July 4, 1852. 3 Harriet Townshend letter, July 15, 1852. 4 Harriet Townshend letter, January, 1854. |