N. S. Townshend and the Civil War

Related Resources

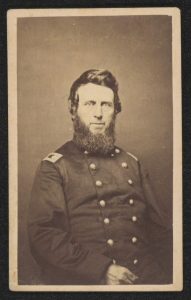

Norton S. Townshend, c. 1863. Townshend Family Photograph Album (Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers, Box 49).

Norton Strange Townshend did not immediately involve himself in the Civil War upon its outbreak in 1861. At 45, he was older than the vast majority of soldiers, and had a responsibility for five children between one and fifteen years old. In 1861-1862, he instead pursued the position of Commissioner of the newly created U.S. Bureau of Agriculture. While in Washington attending to the matter in person, he wrote a letter to his wife revealing his displeasure with Gen. George McClellan’s leadership of the Union Army, certainly a common sentiment at the time:

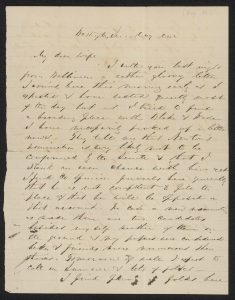

“I find folks here who have no confidence whatever in Genl. McClellan. It is openly disclosed by men who ought to know that he lacks ability & courage & patriotism & that some other of our generals would have finished the war here around Washington many months ago. If he were not now immediately in front of the enemy I think he would be removed at once but this is not for you to repeat. It is sad[,] is it not? The late battle at Williamsburg was near being a total defeat of our troops through his stupidity.”1

Townshend ultimately lost out on the U.S. Bureau of Agriculture commissionership to Isaac Newton, a Pennsylvania dairy farmer who supplied milk to the White House, but was able to secure a different role for himself. Through his connection to Salmon P. Chase, who had been appointed Secretary of the Treasury, Townshend was commissioned to one of sixteen Medical Inspector positions with the Union Army, at the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

N. S. Townshend’s letter to his wife discusses Civil War news. Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 32.

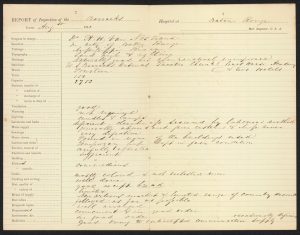

The role of Medical Inspector was created mid-war in order to carry out a number of duties, including monitoring sanitation conditions and the spread of disease in camps, hospitals, and prisons; ensuring adequate food and medical supplies; scrutinizing the methods, tools and practices of surgeons; and checking the validity of records kept by the Medical Department. Medical Inspectors wrote frequent reports describing the conditions they observed in hospitals and camps (below left). They tallied deaths from illness, checked the cleanliness and orderliness of kitchens, sleeping quarters, and lavatories, described the soldiers’ diets, and monitored drainage, water supply, and sewage. Their work was essential at a time when approximately 70% of Union soldier deaths were caused by disease.

Townshend was first stationed in New Orleans, where he arrived by steamship on May 4, 1863. During his first year of service, he was required to make a round between Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, inspecting various camps and hospitals. While in New Orleans, he expressed great interest in African American churches and schools, many of which he visited. He also depicted recruitment efforts by and among African Americans in an essay he wrote many years after his return, entitled “Stories from the War.” Though the piece has the ring of non-fiction, it is unclear whether and how much Townshend embellished the words of an African American Union Army recruiter whose speech he recounts:

Civil War Medical Inspector Report, 1863. Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers, Box 22, Folder 15.

“Perhaps some of you think it is going to take a heap of money to carry on this war, and maybe you don’t know where it is all coming from. I can tell you something about that. Some of the Lord’s people were brought over here more than two hundred years ago, and they and their children, and grandchildren, have been at work on plantations ever since, and all this time have had no pay. The Lord, however, has kept the account for he knows that ‘the laborer is worthy of his hire.’ He knows where all the money is that his people have earned; it may be stored away in London or Paris, or Amsterdam. I have never seen those places, but I have heard of them. Now Massa Linkum when he wants some of this money he just takes what they call a five-twenty. I don’t know exactly what that is, but he shows it to the bankers of the great cities where the money is kept, and the bankers there turned it over to Massa Linkum, and I don’t know whether the planters here who had the labor of the Lord’s people without paying them wages, or the people of the north who helped them to do it have not got to account for all this. Some times I think like enough they have, but one thing is sure, the Lord’s people have earned the money, and the Lord has kept the account, and now he will see that Massa Linkum has all the money he needs.”

Whether true account or work of fiction, “Stories from the War,” reveals Townshend’s deep interest in the societal impact of the war and in the lives of African Americans, whose willingness to fight for their own freedom he clearly admires.

N. S. Townshend kept statistics on how disease affected white and African American soldiers. Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers, Box 22, Folder 14.

Townshend’s letters reveal that the majority of his time was spent evaluating conditions in hospitals, but that his duties did not end there. In a letter to his wife dated October 26, 1863, he wrote: “altho I have already been here for 4 [days] there is a great deal of old hospital property for me to examine. There are two more hospitals to inspect & some troops & a difficulty between some officials which it is made my duty to investigate &c.” It seems that in the day-to-day realities of the war, Medical Inspectors took on the miscellaneous responsibilities and duties that at times did not much match their job description.

In January 1864, Townshend was stationed in Louisville, with an inspection route around Kentucky, Tennessee, and Georgia. The next year, he completed inspections in Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, and Nebraska while based in St. Louis, where his wife Margaret’s sister Miriam and her husband, daguerreotypist Thomas Easterly, lived. He frequently called upon the couple, and his news-filled letters to his wife are one of the few records concerning Easterly’s life that scholars have.

With the large number of patients still in hospitals, Townshend continued to work as a Medical Inspector for several months after the conclusion of the Civil War. He was finally honorably mustered out of service on October 31, 1865. In November, he wrote to his son Jamie, “I have never felt so anxious to get home as I do now. I am not tired of my duties, which are pleasant enough, but I have been so long from my family & home that I feel tired of the absence.”

|

1 Norton Townshend letter, May 1862. 2 “Stories from the War” |