Norton Strange Townshend’s Education

Related Resources

“I have no fears of disgracing the profession of medicine by learning all I can of practical or theoretical farming, believing the latter to be most important & honorable of occupations. Hence whenever I am away from hospitals & the sick & traveling or visiting in the country I make all the observations & inquiries in my power.”

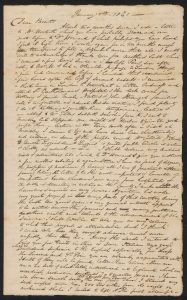

–Norton Strange Townshend, letter of January 1, 1841

When the family moved to Ohio in 1830, Norton–now a strong and stocky adolescent–was needed on the farm and was therefore not enrolled in school. Although he experienced an interruption in his formal education, he gained practical knowledge of a number of innovative farming techniques and was instructed by his father in Latin and other subjects. He also read widely from the family library of over one hundred books on religious, agricultural, and historical topics, many of which had been brought over from England. At nineteen, Norton Townshend joined the First Congregational Church of Avon, which his father had helped to establish, and began teaching Sunday school. In 1836-37, he gained further pedagogical experience while teaching for a year in the district school. His educational preparation, if at times informal, must have been substantial.Letters from relatives suggest that Townshend was considering several professions, including farming and the clergy, but in 1837 he decided to study medicine in order to become physician. In an 1870s manuscript entitled “How a Farmer’s Boy Became a Botanist,” Townshend reflected back on his formative years: “Perhaps someone may be inclined to ask why the farmer’s boy had left the farm to commence the study of medicine.”2 Townshend then explained that medical school provided the best scientific education at a time when most schools emphasized theology and classics, subjects that did not shed light on agricultural improvement. In the end, Townshend chose an educational path that exposed him to an array of practical experiences and the offerings of several medical colleges across two continents.

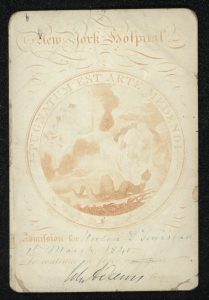

Admission ticket to New York Hospital, 1840. Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers, Box 22, Folder 21.

Townshend received his earliest medical training with Dr. Richard L. Howard, a family friend who maintained a practice in the nearby town of Elyria. In the fall of 1837, Townshend left on foot for Cincinnati Medical College, entering a two-year medical program. After one year, Townshend transferred to the prestigious College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City, where he studied under prominent chemist and botanist, James Torrey, and observed surgeries in New York Hospital. In May 1840, he received his M.D, and after ensuring that his father’s health was sound enough to permit his absence, he sailed for Europe, where he intended to round out his medical education and participate in anti-slavery and temperance activities.

Townshend landed in Liverpool and then made his way to Manchester, where he was welcomed by temperance men who had heard of his visit from the local newspaper. In a letter to his parents, he describes the particular opportunities afforded by medical study in heavily industrialized Manchester:

“Being introduced as a surgeon from America, I was treated very politely and invited to go all over their buildings, see the patients & witness the operations. The Manchester Infirmary is a much better place to see or practice operations than the New York hospital. Manchester is the larger place–the machinery is constantly causing accidents & the people brought up in large manufacturing establishments have their constitutions so injured that wounded limbs have often to be removed to save life. I was there on the operating day & actually saw as many amputations of limbs as I had seen in New York the whole winter. The surgeons told me they were compelled to perform more operations in that Infirmary than they supposed were performed in any one hospital in the world.”3

N. S. Townshend’s letter to his parents from Europe, January 1, 1841. Norton Strange Townshend Family Papers, Box 1, Folder 4.

Townshend then sailed for Paris, where he observed surgeries at the École de Médecine, Université de France. He also met a number or prominent scientists, such as Edouard Seguin, a physician and teacher who argued that the mentally challenged could be taught skills that would make them more self-reliant and productive. Townshend would advocate this idea upon his return to Ohio, and would co-found the Ohio State Asylum for the Education of Idiotic and Imbecile Youth in 1857. According to his daughter Harriet, Townshend also met and discussed chemistry with Louis Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype, while in Paris. His next stop was Scotland, where he studied at the University of Edinburgh in the late winter and early spring of 1841. He then traveled to Dublin and back to London. By the time he returned to Avon in May or June 1841, he had received an education that far exceeded one typical of a country doctor. For Townshend, who would devote much of his life to educational causes, such a circuitous education, with forays into surgery, agriculture, psychology, and politics, made a great deal of sense.

|

1 “Of Education…” (Joel Townshend writing fragment). 2 “How a Farmer’s Boy Became a Botanist” 3 Letter from Norton Townshend to parents, May 25, 1840. |