Graphics Cataloger Jakob Dopp outlines his observations from researching and cataloging hundreds of photos from a collection recently acquired by the Clements Library. Learn more about this collection from the University of Michigan’s Press Release and Video.

Some might say “the camera never lies.” However, when it comes to many 19th-century photographs of Native Americans, this statement can prove to be extremely problematic. The Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography is chock full of examples that illustrate how sometimes there is far more to these photographs than just what meets the eye.

The context in which a great deal of 19th-century photographs of Native Americans were produced did not exactly favor objectivity. Against the backdrop of westward expansion by the United States, many indigenous tribes wound up being violently subdued and/or forced onto reservations. Many Native Americans soon found themselves at the mercy of boarding schools whose curricula was designed to erode their culture, Indian Agents and civilian merchants who were corrupt to the bone, an ever-increasing number of white American settlers, Catholic and Protestant missionaries competing for their conversion, and photographers eager to capitalize on the American public’s insatiable appetite for “wild” Indian photographs.

In some instances, Native American subjects did not have much say in terms of how they were photographed. Recently captured prisoners of war and boarding school students, in particular, had little choice in how they were depicted. Indians on reservations were also sometimes coerced into taking photographs with the promise of much needed money and/or material goods in exchange. Studio props such as embroidered buckskins, bows & arrows, fake tattoos, war clubs, tomahawks, and guns were also commonly supplied by photographers who had a vested interest in making sure their Indian subjects appeared as “savage” as their predominantly white customers expected. In some cases, photographic prints were even manipulated in order to make a subject’s skin appear darker than it actually was. In addition, the highly publicized military exploits of the Lakota and their allies during the 1860s and 70s as well as the popularity of western shows operated by the likes of Buffalo Bill resulted in the dress of Plains Indian tribes (in particular the feather war bonnet) becoming the visual gold standard of what Americans presumed to be authentic Indian-ness. Many photographers began to subsequently provide their Native American subjects with Plains Indian clothing regardless of whether or not that individual’s tribe would have ever actually worn such items.

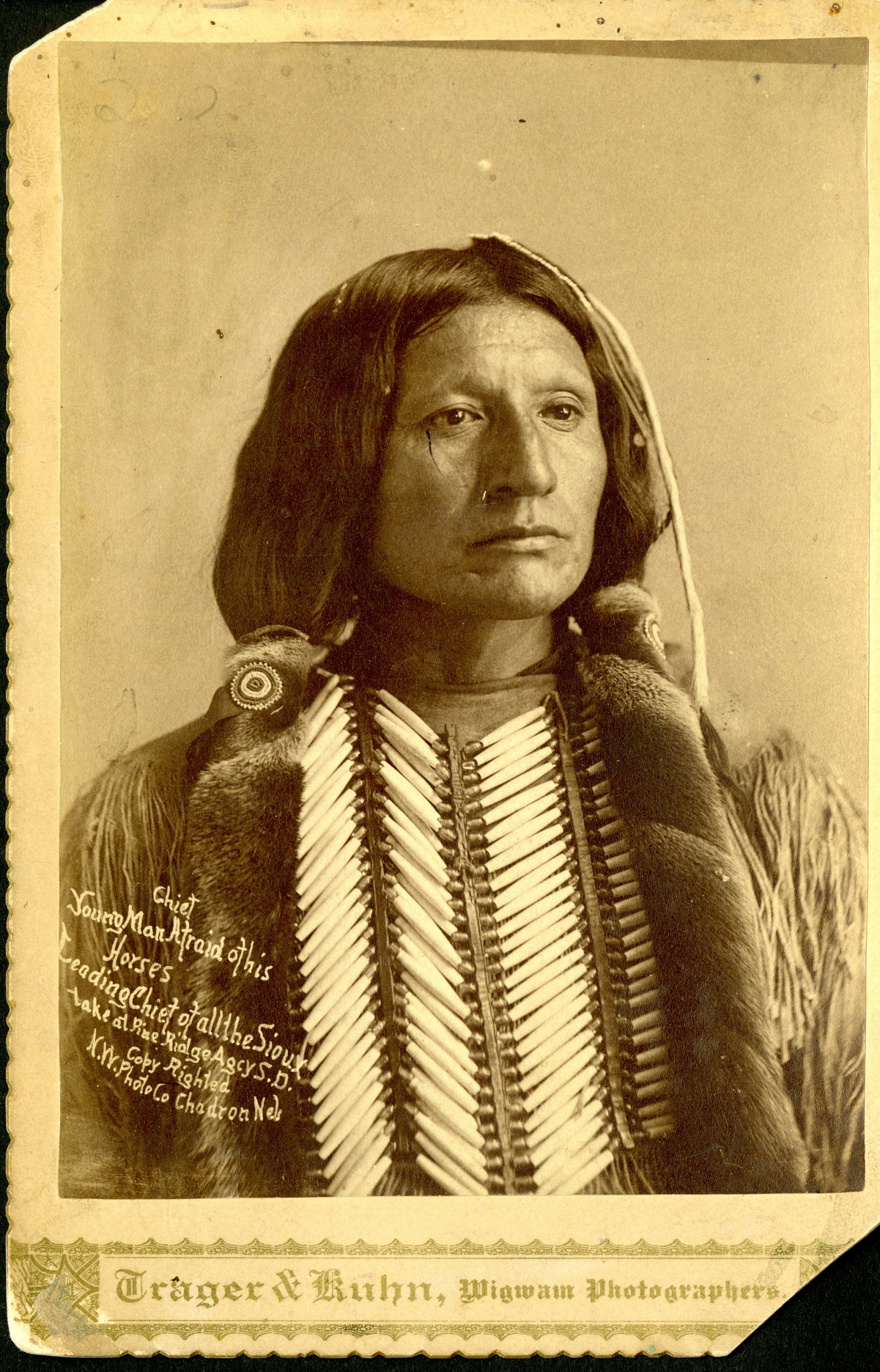

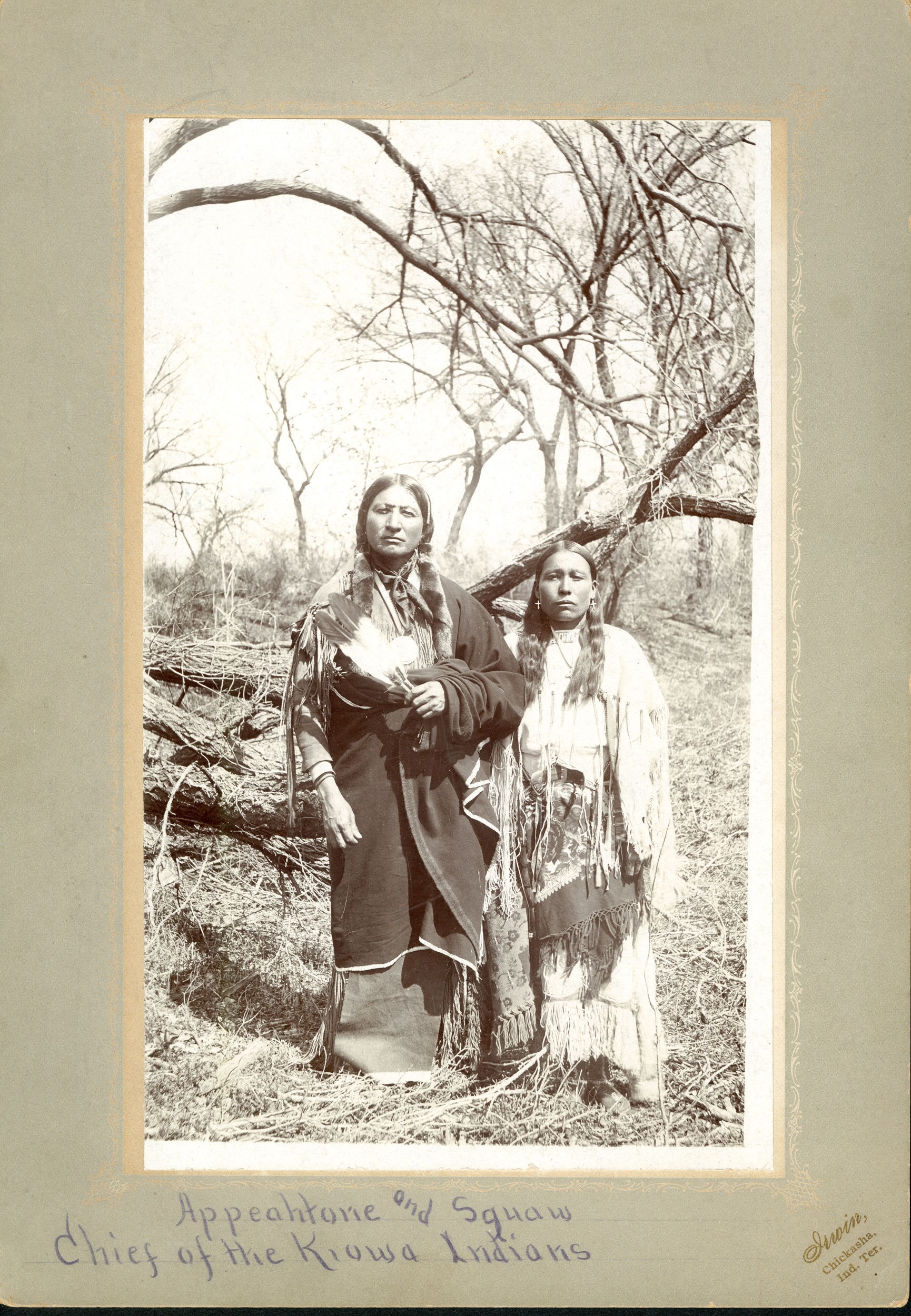

Many 19th century Native American photographs also contain misidentified persons. Such errors may have been made by the original photographers or by previous owners of a given photograph. On account of the complexity of Native American naming customs and the issues inherent with phonetic spelling and translation of indigenous names into English, the extent to which attribution errors persist is not surprising. Most mistakes of this nature were likely unintentional, though in some cases a subject may have been identified as a more famous warrior or chief in order to make that image more profitable or interesting. One excellent example of this issue from the Pohrt Collection is a supposed portrait of Oglala Lakota chief “Young Man Afraid of His Horses” taken by Trager & Kuhn in 1890. As it turns out, this is actually a portrait of Ahpeatone (Wooden Lance), the last traditional chief of the Kiowa. Ahpeatone, whose mother Kale-pi-thay (Sioux Woman) was Lakota, had apparently been sent by the Kiowa in 1890 to visit his relations on the Lakota reservations and learn about their version of the Ghost Dance movement. We can only guess as to how the photographers managed to associate the wrong name with Ahpeatone’s portrait, but it likely had more to do with faulty record keeping than anything else.

Photographers Gus Trager and Frederick Kuhn were active in the Nebraska-South Dakota border region during the rise of the Ghost Dance movement and the Wounded Knee Massacre. They most likely erroneously identified this portrait of Kiowa chief Ahpeatone as Young Man Afraid of His Horses by simply getting the details mixed up in their voluminous inventory of negative image plates.

By examining this and other portraits of Ahpeatone, we can confirm without a shadow of doubt that the Trager & Kuhn portrait is of the famed Kiowa leader and not Young Man Afraid of His Horses.

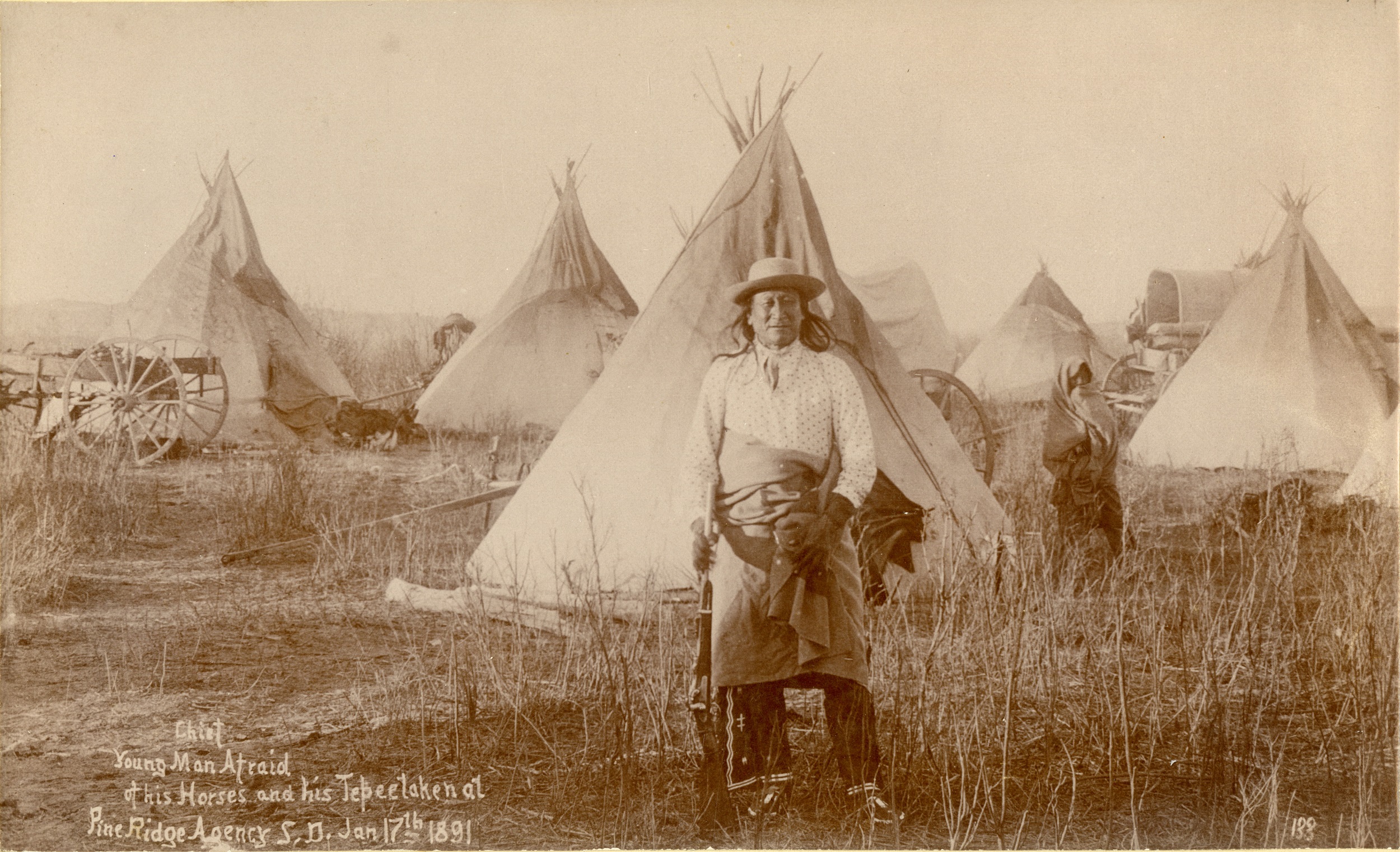

Trager & Kuhn did manage to correctly identify Young Man Afraid of His Horses in this portrait showing the Lakota chief standing in front of his tipi. It is worth noting that “Young Man Afraid of His Horses” is a clunky mistranslation that would seem to suggest this was a man afraid of his own horses. This name was actually passed down from his father (Old Man Afraid of His Horses), the true meaning of which implied that they (his enemies) became afraid at the mere sight of his horse entering the battlefield.

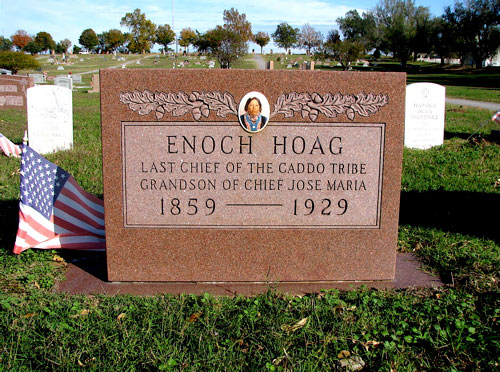

Identified as “Enoch Hoag. Delaware.” in the photographers’ caption, further investigation revealed Hoag to be the last traditional chief of the Caddo.

Errors regarding a subject’s tribal affiliations are also not unusual, and the Pohrt Collection contains many instances of this. One of the most common tribal attribution errors involves the Hidatsa and Gros Ventre tribes, who were often mistakenly grouped together. For instance, the Hidatsa chief Tsesha-Hadhadish (Poor Wolf) is identified in official captions by several different photographers as being a chief of the Gros Ventre. Another prime example is the Lenny & Sawyers portrait of Enoch Hoag, who was identified as belonging to the Delaware. As is unequivocally declared on his tombstone, however, Hoag was in fact “The Last Chief of the Caddo Tribe.” Hoag was apparently married to a Delaware woman, which could help explain the confusion regarding his tribal identity on the photographers’ part.

While it is true that a substantial number of 19th century Native American photographs were produced under extortionate circumstances and/or contain erroneous information, many were also created with the explicit approval and cooperation of Native American subjects. Sometimes (albeit rarely), certain images even appear to have been strongly influenced by the Native American subjects themselves. In particular, one might find photographs of recently married couples, delegation groups of proud leaders, new mothers eager to show off their newborns, and relatives keen to memorialize deceased friends or family members. One of the most poignant examples of the latter in the Pohrt Collection is a studio group portrait by William M. Oaks depicting two unidentified Prairie Band Potawatomi women. The women (likely sisters) can be seen posing in traditional clothing behind a vacant chair that has been decorated with personal effects which surely belonged to a deceased individual (or individuals) known to both. A family group portrait photograph that likely included the deceased person(s) has also been placed on the chair. Thus, it would seem entirely plausible that these women requested this photograph to be taken in order to memorialize their dearly departed.

When it comes to 19th-century Native American photography, nothing can be taken strictly at face value. Upon analyzing these photographs, one must take into account the historical context in which the images might have been created, the photographers’ vested interests in creating commercially viable products that matched their customer’s expectations of what “real” Indians looked like, as well as the potential for errors regarding identification of tribal affiliations and personal names. Indeed, in some ways, many of these images reveal more about the practices of 19th-century American photographers and prevailing racist attitudes of the time regarding Native Americans than they do about indigenous peoples and cultures.

Jakob Dopp

Graphics Cataloger

Looking closely at the chair situated between the two unidentified Prairie Band Potawatomi women, one can see multiple objects: a studio group portrait with four individuals (possibly four women); beautifully embroidered articles of clothing; and a small leather handbag. Due to the extremely personal nature of what is surely a memorial arrangement, it is almost certain that these women were the driving force behind this photograph being taken.