Americans in general—and younger people in particular—are often criticized for being woefully deficient in a geographical understanding of their country, continent, hemisphere, and world. In many ways such criticism is justified, and the noticeable reduction in geography instruction in schools has done nothing to improve the situation. This is unfortunate because regular use of maps can fill the gaps in understanding of the form of our world, and atlases, whether printed or digital, are also fine sources of such information.

|

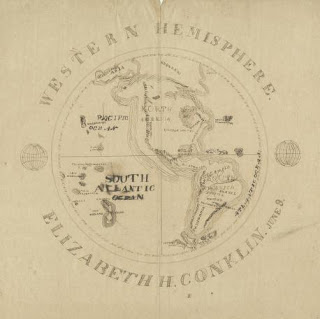

| Western Hemisphere / Elizabeth H. Conklin, June 8. Pen and ink student’s hemisphere map. |

For the past few years the Clements Library has been actively collecting a most interesting type of manuscript map. Often described by dealers and collectors as “schoolgirl” maps, these exercises in cartography demonstrate that training in geography was one element of a good nineteenth-century education. This type of map is frequently encountered in dealers’ catalogs these days, so there has been a good selection of potential acquisitions. We now hold fifteen examples dating from 1818 to 1884. Our catalog entries describe them as “student” maps because the majority of our examples were drawn by young men. They include a variety of subjects—the world, the Western Hemisphere, North and South America, the United States and its component states, as well as Biblical cartography. There is even a map titled “The Ocean of Love.” The students obviously worked using a printed map as the source.

Most of our student cartographers are identified, and sometimes the name of their school is known. Hannah French, for example, studied at the New Hampton Female Seminary of New Hampton, New Hampshire, about 1820 when she drafted a map of her country. Some of the student maps are associated with manuscript collections held by the Clements, such as Elizabeth H. Conklin’s interpretation of the Western Hemisphere from the Conklin Papers and that of North America found in the James Thomas Papers and probably drawn by one of his school-age sons.

Some of our student maps are surprisingly sophisticated. Melvin Wright was at school in Londonderry, Vermont, in 1841 when he drafted a heavily colored map of his state and embellished it with six marginal drawings including a view of the capital, Montpelier. H.L. Hobart demonstrated that he or she was a better cartographer than a speller on the circa 1853 “Map of Michigan & Wiscosin.” And Albert King even ventured into the allegorical. In addition to his maps of “Hindoostan” and the Middle East, he prepared the “Ocean of Love,” with its “Land of Matrimony,” “Quicksands of Inconstancy,” and “Dead Lake of Indifference.”

The Clements will continue to collect “student” maps, but we have already reached a critical mass, where the available materials can support research into nineteenth-century education. Used with our school atlases, school textbooks, and manuscripts with education content, a researcher can discover much about teaching and learning in the 1800s.

Associate Director and Curator of Maps