Post by Jayne Ptolemy, Manuscripts Curatorial Assistant

The reasons to appreciate and enjoy the Clements Library’s collections are as varied and numerous as the holdings themselves. Whether they are exceptionally rare, provide detailed information, or are particularly evocative, the research materials at the Clements are valuable on multiple levels. And sometimes, it’s the sheer beauty of an item that draws our attention.

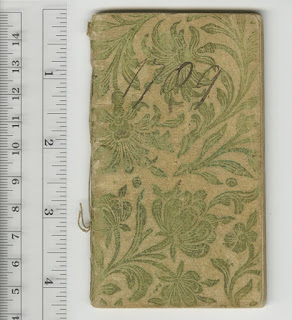

The Book Division holds some striking examples of decorative papers. Whether used as covers or endpapers, these vivid designs speak of both a personal aesthetic and a particular affection for the printed item at hand. Take, for example, these Poor Will’s Almanacks, covered with colorful Dutch gilt paper, a type of printed paper that was produced through the use of blocks or engraved rollers, often using gold size and dust. Additional colors were sometimes stenciled or dabbed on to yield a visually stunning paper. While almanacs are quotidian in their nature– dealing with calendars and seasonal predications– these late eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century volumes have been bound in a highly stylized paper, perhaps indicating the users’ interest in beautifying something that would have been consulted regularly.

|

|

| Poor Will’s Almanack (Philadelphia: Joseph Cruikshank, 1789 and 1799). These are two of several almanacs in the Clements’s collection that feature Dutch gilt covers. | |

Another example of a Dutch gilt cover can be found on this 1724 pamphlet, Brief aan de heer N.N., koopmaan in Nieuw-Nederlandt. The golden shine does not translate well in photographs, but it catches the light beautifully in person. While visually appealing in itself, this type of paper also hints at an expressive sense of design that adds to our sense of the text’s readers.

|

| Wilhelmus à Brakel, Brief aan de heer N.N., koopmaan in Nieuw-Nederlandt (Deventer [Netherlands]: Bernard de Vries, 1724). |

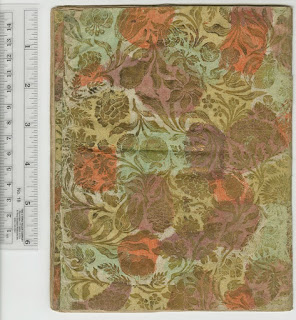

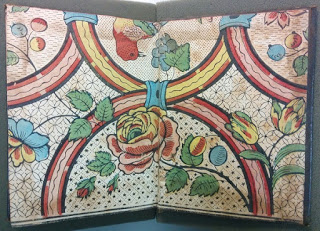

Other volumes in the Book Division use different types of paper as decoration. This 1768 Spanish volume, Carta del venerable siervo de Dios, D. Juan de Palafox y Mendoza al sumo pontifice Inocencio X, has hand-colored endpapers that were produced by Orleans, France paper maker Ambroise Benoist-Huquier, who appears to have been active in the second half of the eighteenth century. The nature of its design points to it possibly being wallpaper repurposed as a colorful addition to the book. Opening the book to this floral and avian design adds an aesthetic quality to the reading experience and provides clues about this volume’s history.

|

| Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, Carta del venerable siervo de Dios, D. Juan de Palafox y Mendoza al sumo pontifice Inocencio X (Madrid: 1768). |

The use of these papers connects us to the users of the books, sometimes giving us a glimpse into the ornamental elements of their home lives. It is possible that some of these papers were scraps from other projects. Looking at this small 1811 edition of Rhode-Island Sermons, only 12 cm. tall, it seems feasible that a remnant piece of wallpaper used elsewhere may have been repurposed to cover this religious text.

|

| Rhode-Island Sermons; first published in the Providence Gazette, A.D. 1810. Vol. 1 (Hartford: Peter B. Gleason, 1811). |

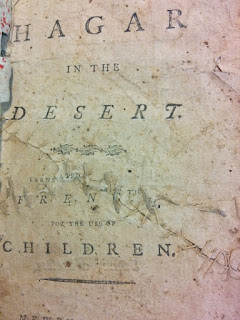

Likewise, our 1790 children’s book, Hagar in the Desert, features a hand-made covering, possibly sewn from leftover wallpaper. This text reflects the book owner’s direct influence. The reasons why these decorative papers were chosen for these specific items remains obscure, but they do suggest how individuals showed special attention to beloved volumes.

|

| Stéphanie Félicité, comtesse Genlis, Hagar in the Desert. Translated from the French for the Use of Children (Newburyport: John Mycall, [1790?]). |

Hagar in the Desert‘s title page further proves this point. A hand-stitched tear reveals that the owners not only read this book heavily but cared enough about it to repair it to ensure future use.

These well-loved volumes are a joy to handle and admire, as we glimpse the past users’ influence and experience through them. As caretakers of these books, the Clements Library continues the tradition of honoring and valuing these distinctive texts. However, they can prove to be a conservation challenge. Preserving these decorative papers and evidence of readership takes special care and attention. Fortunately, the Clements Library’s Conservator, Julie Fremuth, is up to the task. If you find yourself as taken with these volumes as we are, please consider contributing to our Adopt-a-Piece-of-History program. Hagar in the Desert is available for adoption, and your sponsorship can help ensure that it is safely repaired and housed, making it available to be cherished and used for decades to come.