Post by Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphic Materials

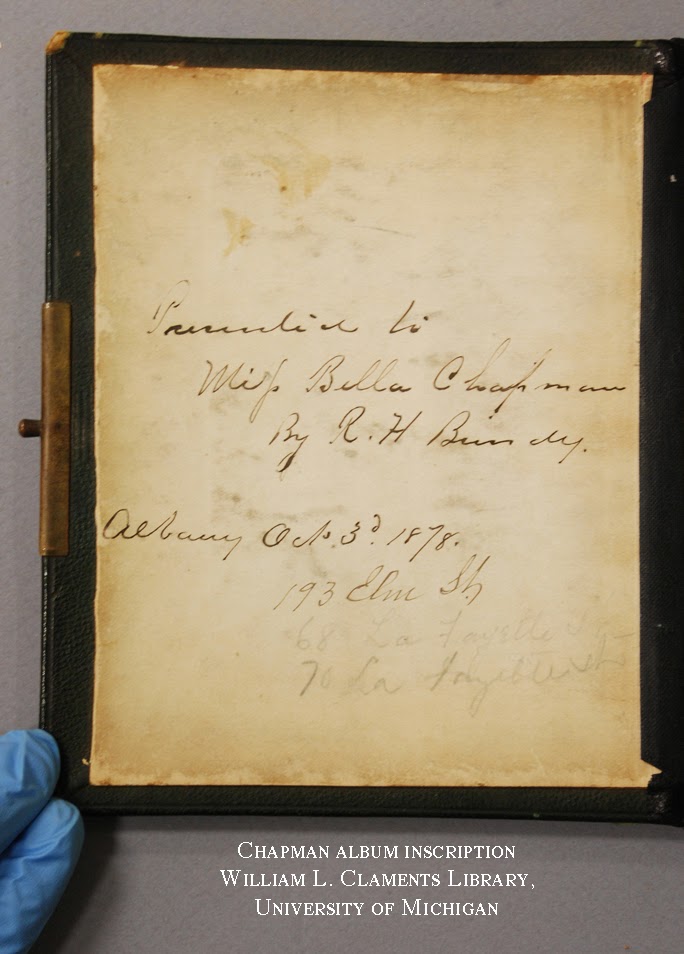

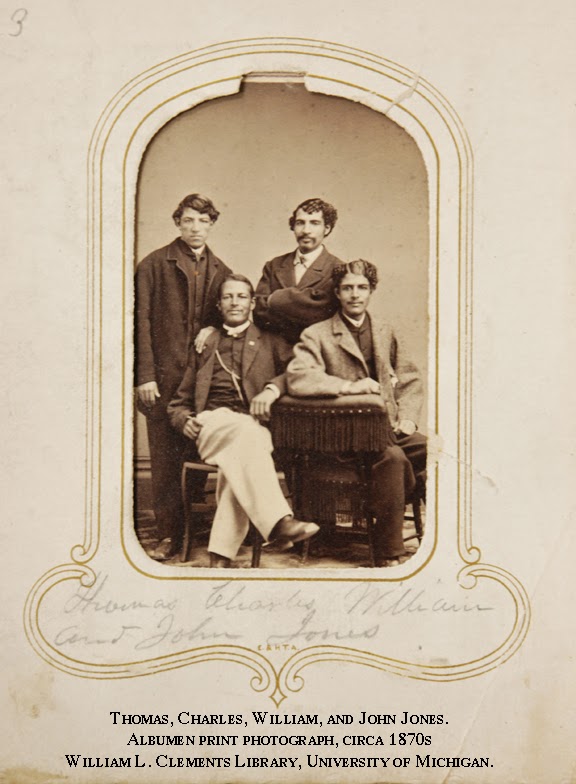

During fall semester 2014, University of Michigan Professor Martha Jones’s African American Women’s History class embarked on a detailed examination of a pair of photograph albums from the Clements Library collection. The albums originally belonged to Arabella Chapman (1859-1927), an African American woman from Albany, New York. They were assembled from 1878 to 1900 using portraits taken from the 1860s to the turn of the century. The photos include Arabella, her family, friends, and admirers, and well-known public figures. The class discovered that these two albums have depth of meaning well beyond what is initially apparent.

Portrait photographs have been presented as a declaration of status and identity since their first widespread use in the 1840s to the Facebook era today. In the first decades, carefully composed studio photographs often showed people in their finest dress or work attire, holding symbolic objects like diplomas, books, or tools. As paper prints replaced the hard-cased Daguerreotype, photos began to be combined into albums, presenting narratives of the social fabric of families and communities. By the late 1880s, amateur photographers with inexpensive Kodak cameras encouraged a casual playfulness that greatly expanded the range of meaning.

“The power of images to construct ideas about race and difference had its origins in early 16th century encounters between Europeans and Africans. With the advent of photography in the 19th century, African American activists reflected on the possibility for this new medium. Photographs might be used to perpetuate racist stereotypes, warned Frederick Douglass. However, photography might be a democratizing technology that would provide Black Americans with the opportunity to craft their own images. It is this latter possibility that Chapman’s albums evidence,” said Professor Jones. Her class discovered how African Americans creating and purchasing photographs could steer self-expression and personal identity towards images of empowerment rather than degrading caricatures.

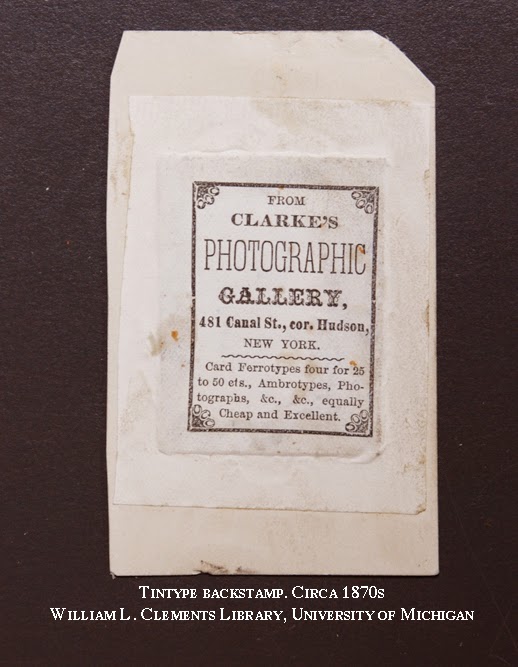

The class began with a close examination of all types of early portrait photography. The Chapman albums were then minutely documented, photographed, and assessed for content — the who, what, when, where, why, and how. The albums’ individual card-mounted photographs were carefully removed by Clements conservationist Julie Fremuth, revealing hidden information about subjects, places, photographers, and even one additional photograph hidden behind a photograph.

Family genealogy, career paths, and political alliances were uncovered, establishing the Chapmans at the center of active African American communities in eastern New York and Western Massachusetts. The hidden back-stamps of some photographs indicated leisure travel to areas such as Saratoga Springs.

The students concluded that the Chapman albums are an example of a confident, educated, and socially engaged African American woman representing herself to her peers, her family, and posterity. In spite of whatever racist barriers the Chapman family faced, the story told through the images is about accomplishment, pride, and overcoming oppression. Family values are established by the inclusion of commercial portraits of Abraham Lincoln, John Brown, and Frederick Douglass in among the images of family and friends.

The known information about the Chapman family has been greatly expanded by the class work, but some mysteries remain. Who are the unidentified people in the albums? The two albums overlap to some degree — were they intended for different audiences? How certain can we be about authorship? The albums appear to have been assembled over several decades and annotated by more than one person, including a child of Arabella’s. Were they edited by others as well? These and other questions will sustain further research into the Chapman albums for others to pursue.

Nor is the work of the class complete. By spring 2015, they will launch a website devoted to the Chapman albums. It will include scans of the album pages, genealogical information, maps, texts on the history of photograph albums and the role that photography played in African American lives, a portal for crowdsourcing more information, and more.

It is exciting to work with Professor Jones, her innovative teaching methodology, and her ambitious and alert group of students. In an era of electronic media, this class linked past practices to the present in an important and meaningful way.

Links:

Wikipedia article on Arabella Chapman

Finding aid for the Arabella Chapman Carte-de-visite Albums, 1878-[1890s]

Pinterest board for the Arabella Chapman Album