Post by Jayne Ptolemy, Manuscripts Division Curatorial Assistant

In the late evening hours of July 25, 1814, one of the bloodiest battles of the War of 1812 commenced, continuing until after midnight. Unplanned and fought in the dark of night, the Battle of Lundy’s Lane claimed over 250 fatalities and 1,700 casualties across both British and American troops. While American forces had recently defeated the British at the Battle of Chippawa and were continuing their advance into Canada, the Battle of Lundy’s Lane halted their forward progress. The Americans instead retreated to Fort Erie. Despite the heavy losses, neither side could claim a decisive victory.[1]

|

| Battle of Niagara, in The Port Folio, Third Series, vol. 6, no. 3 (September 1815), p. 220. |

Here at the Clements Library, we have multiple manuscripts collections that shed light on the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. Our War of 1812 Collection, the William Williams Family Collection, and our David B. Douglass Papers, for example, contain materials that touch upon this military encounter. Recently, the Library received a generous donation of over 430 Douglass family letters, nearly doubling the size of its existing David B. Douglass collection. This incredible array of personal correspondence includes letters written during Douglass’s march to the Niagara battlefield and immediately following the bloody engagement at Lundy’s Lane.

David Bates Douglass served in the 1814 Niagara Campaign during the War of 1812 as a second lieutenant of engineers, having recently joined the army after his graduation from Yale. Following the war, Douglass accompanied various surveying parties, including the Lewis Cass expedition in 1820, and led a successful teaching career at the United States Military Academy at West Point. The Clements Library’s original Douglass collection includes a bound volume of his lecture notes, wherein he recalls the July 25th battle, and a copy of his journal documenting his march to the front. The recent addition of Douglass’s personal letters provides an exceptional counterpart to these materials relating to Douglass and the War of 1812.

Lieutenant Douglass described his impressions of the British forces seen from Queenston Heights preceding the Battle of Lundy’s Lane in his lecture notes, Reminiscences of the Campaign of 1814, first delivered in 1840. “[Y]onder in plain sight are the colors of the Enemy waving proudly over the ramparts of Fort Niagara and Fort George, and a straggling ray now and then reflected tells of bayonets fixed there too… This, then, was no mere parade, — no stage play for effect; it was a simple and sublime reality—it was war.”[2] Written decades after the war with a public audience in mind, Douglass’s lecture has a theatrical ring to it. In our recent addition to the collection, we have several more candid letters penned by Douglass while he was at Queenston in mid-July 1814. In one, he apologizes for the state of his handwriting, explaining, “I am sitting on the ground and writing on the soft top of a leather Trunk, and added to this, my right thumb is just beginning to recover from a most painful sprain which I got for it at Canandaigua.” On July 16, 1814, Douglass wrote to his future wife, Ann Eliza Ellicott. In it he writes of his recent purchase of a locket in Albany, where he knotted together locks of their hair, “It hangs round my neck by the cord you made—a charm to shield me from danger and spur me to noble deeds.” With the addition of these incredible personal letters, our David Bates Douglass collection now reveals these compelling, intimate details. We see a lovelorn man suffering from the everyday trials of camp life that complements our understanding of him as a renowned engineer and military figure.

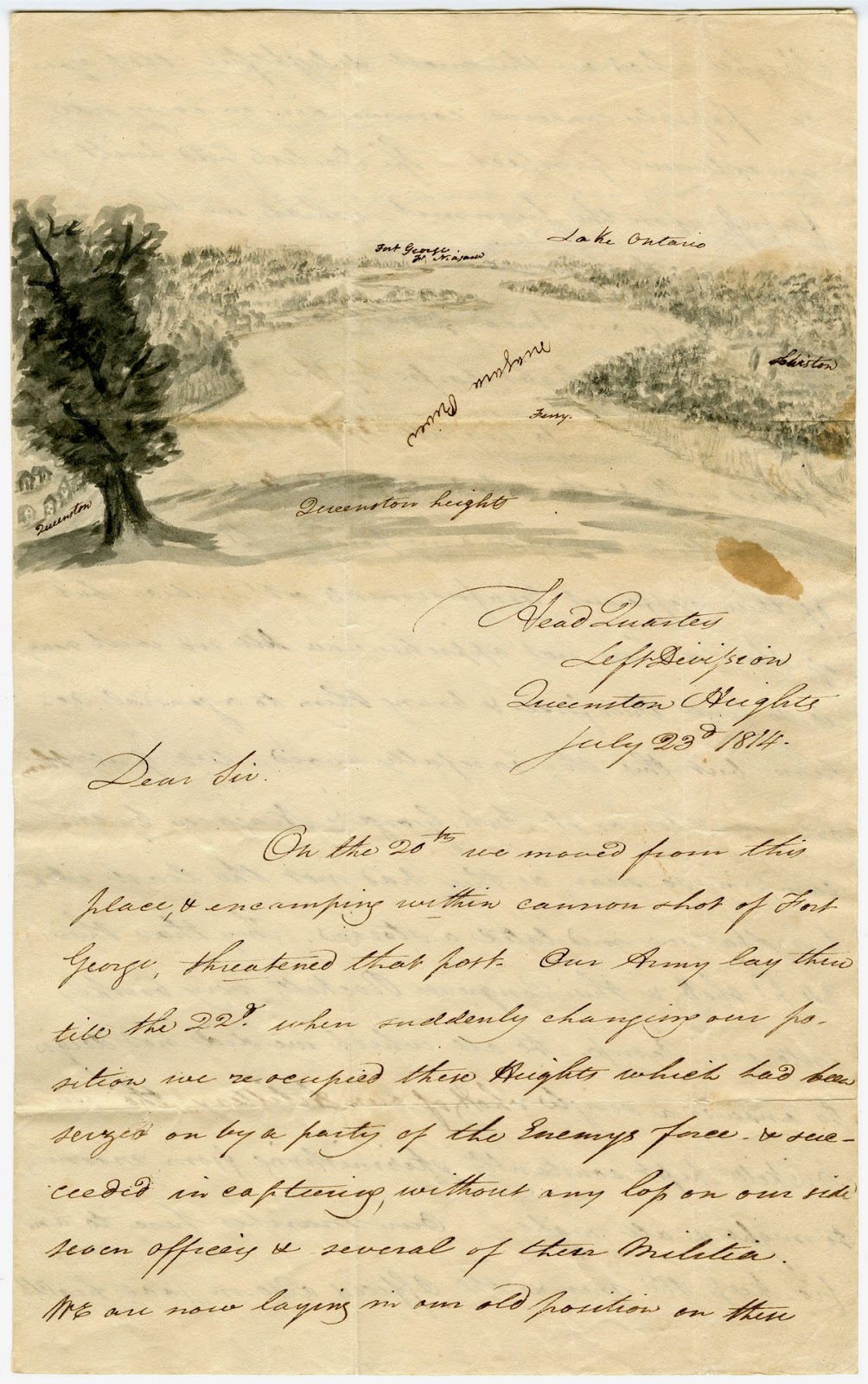

|

| Loring Austin ALS to Jonathan Austin, Queenston Heights, July 23, 1814. William L. Clements Library. Seen here is a first-hand depiction of the view from Queenston Heights. For more on the Clements Library’s War of 1812 holdings, including the full text of this letter, see our online War of 1812 exhibit. |

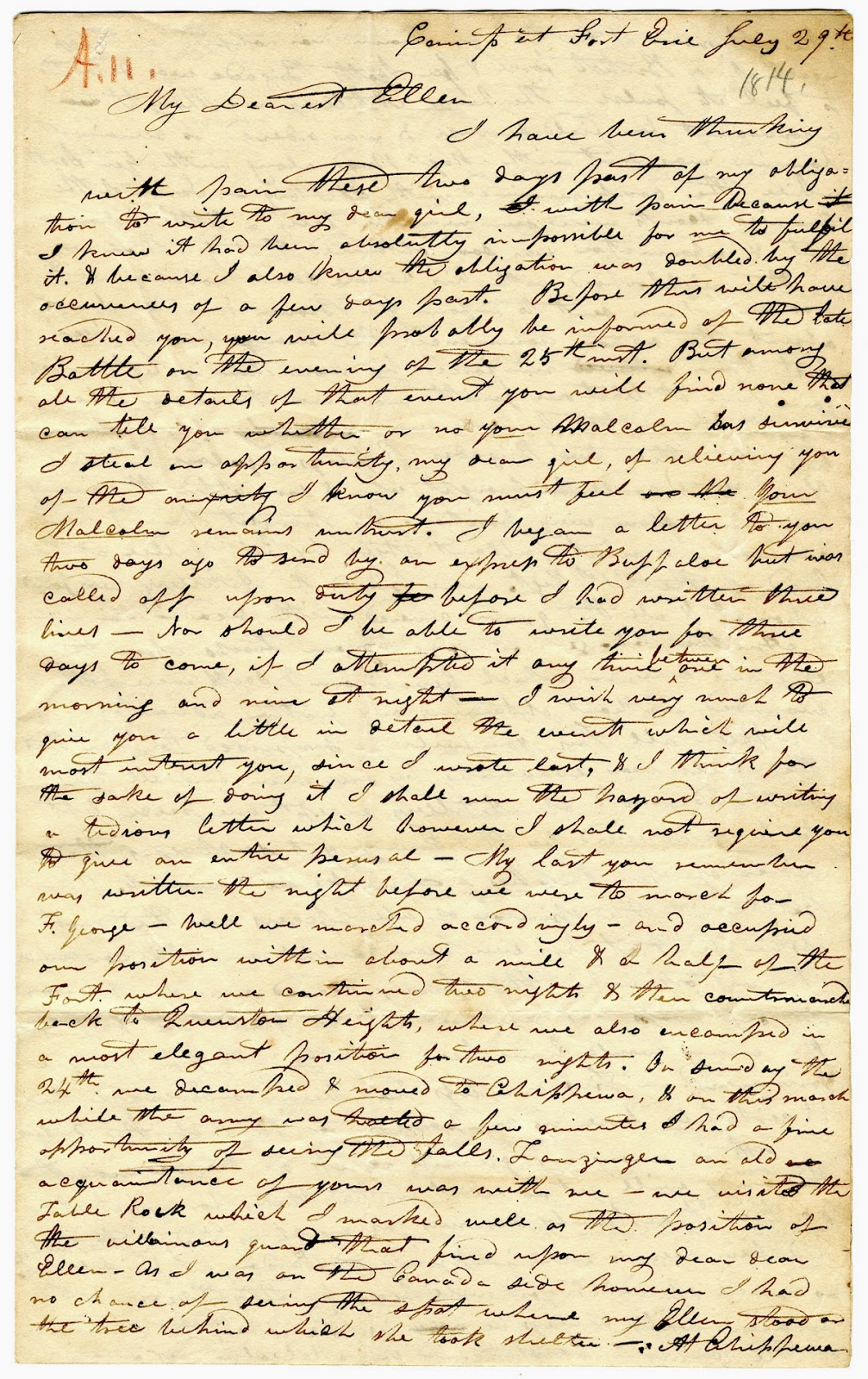

Two letters in the new addition directly precede and follow the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. One written by David Bates Douglass’ mother is dated July 19, 1814. She wrote a scathing letter to her son, lamenting his lack of correspondence. “I beg and bese[e]ch you never let a new moon ap[p]ear without writing if tis but a few lines to your parents,” she writes, underscoring a family’s fear and anxiety for a son serving actively during wartime. The first letter written after the battle is from Douglass to his beloved Ann Ellicott, written on July 29, 1814, assuring her of his safety. He described the Battle of Lundy’s Lane and his role in it, also including small details that can escape narratives of military events. The battle was long-fought and upon its conclusion Douglass took a brief rest, “(if rest it could be called to lay coiled up on spades & shovels in an implement Wagon),” before rising again to prepare his company to move. As he worked, he defied other officers’ expectations of what could be accomplished. In writing to his future wife, he allowed himself these small moments of triumph, aware that she would be “gratified to hear them, but to any one else it would be egregious vanity.” In these private letters, then, we gain a personal perspective on Douglass and the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. In official accounts, both in the Clements Library’s collections and beyond, we see Douglass as a competent, respected officer. Through this new addition, we see him also as very human—enamored, tired, proud.

|

| David B. Douglass ALS to Ann Elicott, Camp at Fort Erie, July 29, 1814. David B. Douglass Papers, William L. Clements Library. |

Military history is enriched by these details—a mother chastising her son on the eve of a battle; a man walking into combat with a locket at his breast to give him courage; a prominent historical figure sleeping amidst shovels. These personal glimpses give breadth and texture to the story, and we are grateful for the recent donation that will enliven and deepen our research.

The addition to the David B. Douglass Papers contain letters and content pertaining to his multifaceted career as a War of 1812 officer, an educator at West Point, a surveyor and civil engineer, and a president of Kenyon College. Equally important are additional letters of his wife Ann Ellicott Douglass; his siblings Julia Douglass and Marcus Douglass; his daughters Sarah, Ellen, Mary, and Emily; and sons Andrew, Charles, Malcolm, and Henry. We anticipate processing the collection and making it available for research later this year.

Notes:

- “Battle of Lundy’s Lane,” Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Academic Edition, accessed 15 July 2014. For a detailed account of the events leading up to and during the Niagara Campaign and the Battle of Lundy’s Lane, see Donald E. Graves, The Battle of Lundy’s Lane on the Niagara in 1814 (Baltimore: Nautical & Aviation Publishing Company of America, 1993).

- The notes for this lecture were subsequently published in the Historical Magazine 3.1 (July, 1873), 1-12.