Post by Brian Dunnigan, Associate Director and Curator of Maps

The events of August 16, 1812, brought an ignominious end to an American invasion of Canada and sent shock waves through the United States. On that day Brigadier General William Hull surrendered the fort and town of Detroit to British Major General Isaac Brock. Some 2,400 U.S. regulars and Ohio and Michigan militia were taken prisoner, and the Michigan Territory, of which Detroit was the capital, became occupied territory. Detroit would remain under British control for the next fourteen months.

Hull’s disaster belied former President Thomas Jefferson’s flippant comment that the conquest of British Canada would be a “mere matter of marching.” Hull’s invasion from Detroit was the westernmost of three planned incursions in the summer of 1812. The others, at Niagara and northern Lake Champlain, were so far behind schedule that any benefit of coordinated attacks was lost. Hull assembled his army in Ohio in timely fashion and marched to Detroit, where he arrived early in July 1812.

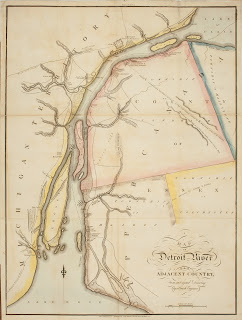

|

| This manuscript map, detailing the fall of Detroit, was sent soon after the capitulation to Earl Amherst by John Hale, an official in Lower Canada (Québec). Map Division, Maps 6-N-5. |

The Americans crossed the river into Canada on July 12 but made only an indecisive effort to capture the British fort at Amherstburg. In the meantime, the British and their Native Amereican allies, possessing naval control of Lake Erie, began to block Hull’s supply line to Ohio. Efforts to reopen the route were unsuccessful. Then, early in August, Hull learned that Fort Mackinac had fallen on July 17. This, he feared, would “open the northern hive of Indians” to operate against him. Hull withdrew his army to Detroit.

The chain of events leading to surrender began with the arrival at Amherstburg on August 14 of General Brock with British and Canadian reinforcements. The British established batteries of cannon to bombard Detroit and Brock led his men across the river on the 16th to join Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his warriors. Together they bluffed and intimidated Hull into surrendering in part out of fear of the fate of Detroit’s civilians if fighting commenced.

The debacle at Detroit would not be reversed until the autumn of the following year. And, like so many War of 1812 events, documentation relating to the fall of Detroit is well represented in the primary source material held by the Clements Library.