Photographs of the Civil War, though a poignant and engaging window into the past, were created with very different goals and standards than those upheld by today’s wartime photographers. The rise of cheaply reproducible paper-based photo printing in the 1860s allowed commercial photographers to produce and sell not only portraits of soldiers and war heroes but images of the war itself. The latter were often grisly, depicting rows of bodies and demolished battle sites as somber reminders of the realities of war–not an unfamiliar genre–but there is substantial evidence that the photographers manipulated their tableaux for maximum effect, physically rearranging corpses and staging scenes with living soldiers to either idealize or enhance the tragedy of their subjects.

“It is important to consider that the nienteenth-century audience was not seeking impartial facts as much as spiritual, sentimental meanings and evidence of the moral cost and justification of the war. Photographers were seeking journalistic truths but not at the expense of what they saw as greater aesthetic and moral truths.” (5)

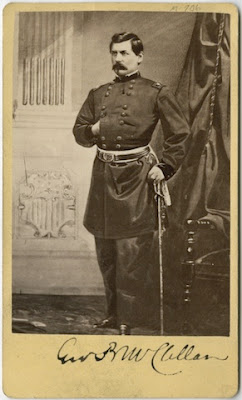

Civil War Portraits in our collections.

James D. Horan, Mathew Brady, Historian with a Camera (New York, 1955).

Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, Original Photographs Taken on the Battlefields During the Civil War of the United States… (Hartford, Connecticut, 1907).

Read Clayton Lewis’ article in the Fall-Winter 2010 edition of The Quarto.