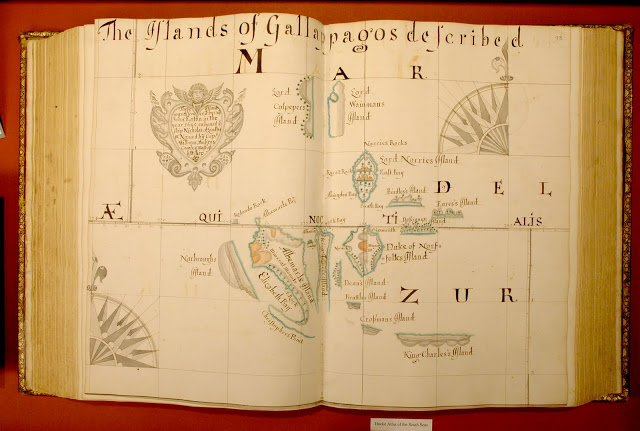

Last year for International Talk Like a Pirate Day, the Clements Library Chronicles highlighted a variety of materials related to pirates, including books, manuscripts, and a broadside poem. This year, we offer just one exceptional item: the Pirate Atlas.

The Clements Library purchased the Hack Atlas in 1979, funded by the generosity of the Clements Library Associates. The atlas was recently featured in a display in the Main Room of the Library, celebrating the Clements Library Associates’ contributions to the Library.

The original September 1979 Quarto announcement:

“As you may have already noticed from widespread newspaper and television coverage, the library has committed itself to purchasing one of the most important historical volumes ever acquired. William Hack’s late seventeenth-century manuscript “South Seas Atlas,” copied from a Spanish derrotero captured by the English pirate Bartholomew Sharp, documents a crucial chapter in American history recorded in no other source. . . . An effort is now underway to raise $50,000 to complete payment for the new treasure, and assistance on the part of all friends of the library will be most welcome in the coming months. The atlas, which is as beautiful as it is historically important, will be on display at the October 16 meeting of the Associates.”

The Quarto for March 1980 contained a special supplement entirely devoted to the Hack Atlas, the history of its creation and an evaluation of its importance by Dr. George Kish of the Geography Department. Professor Kish served as part-time Curator of Maps under the first Clements Library Director Randolph Adams in the mid-1940s.

The entry in One Hundred and One Treasures from the Collections of the William L. Clements Library provides the historical background:

“In 1680, a motley crew of pirates crossed the Isthmus of Panama, looting Spanish settlements along the way. They captured several vessels on the Pacific side, one of which was named the Trinity and which they made the flagship of the expedition. Since the voyage of Sir Francis Drake a century before and a few brief visits by Dutch ships earlier in the seventeenth century, no non-Spaniard had sailed in American Pacific coastal waters, and the Spanish settlements were entirely unprepared to defend themselves.

For more than a year, squabbling among themselves much of the time, the pirates explored and raided settlements and shipping up and down the coast from Acapulco to Chile, finally sailing around Cape Horn and back to the Caribbean where they divided their spoils. Twenty-two of the pirates associated with the voyage then took passage to England on two different ships, arriving in March 1682, where they created a diplomatic crisis between England and Spain. At the urging of the Spanish ambassador, several were tried for piracy and murder, but all were acquitted. They brought back sufficient treasure to pay handsomely for the voyage, but the real prize of the expedition was a set of sea charts captured on July 29, 1681.”

The buccaneer Bartholomew Sharp described the capture of this book:

“In this ship . . . we took also a great book full of seacharts and maps, containing a very accurate and exact description of all the ports, soundings, creeks, rivers, capes and coasts belonging to the South Sea, and all the navigations usually performed by Spaniards in that ocean. . . . The printing thereof is severely prohibited, lest other nations should get into those seas and make use thereof.” (Quoted in the Quarto, March 1980)

Sharp added in another account, “they were going to throw it overboard, but by good luck I saved it–the Spaniards cryed out when I got the book, farewell South Seas now.”

After returning to England, Sharp turned the maps over to William Hack, a leading English mapmaker. Hack produced a series of fourteen copies, of which the Clements Library copy is the most extensive. Sharp and Hack presented the first copy to Charles II.

The Atlas includes 184 manuscript maps and extensive notes on provisions, landmarks, and sailing hazards. There is even a mention of sunken Spanish treasure. In the waters off Panama, it is noted that “on this shoal was lost the Almirant of the King of Spain, in the year 1631, in which was vast treasure.”

In evaluating the Hack Atlas, Professor Kish concluded,

“Hack’s atlas is a landmark in the maritime history of England. It provided, for the first time, a detailed and reliable source of information on Spanish possessions in western South America. The age of buccaneers was already drawing to a close when Charles II was presented with this priceless guide to seas until then unknown. It served not only navigators, but also compilers and publishers of detailed sea charts of the eighteenth century.”

The entry above ("Since the voyage of Sir Francis Drake a century before and a few brief visits by Dutch ships earlier in the seventeenth century, no non-Spaniard had sailed in American Pacific coastal waters") needs to be corrected. Important English/British expeditions to the South Sea did take place after Drake and before Sharp's, i.e. Thomas Cavendish (1586) and Richard Hawkins (1593-93) plus other minor ones with partial success.