|

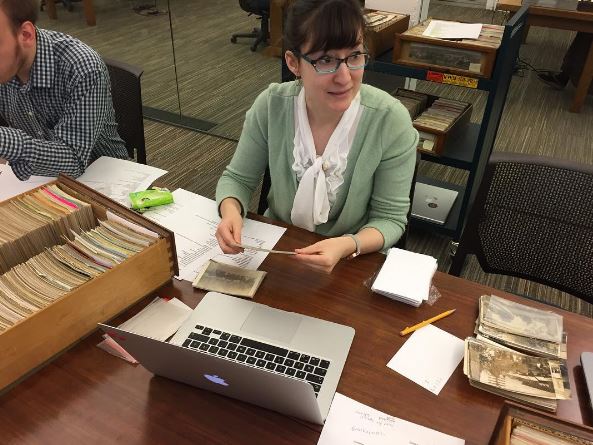

| Image credit: Claire Milldrum |

Post by Noa Kasman, Joyce Bonk Library Assistant

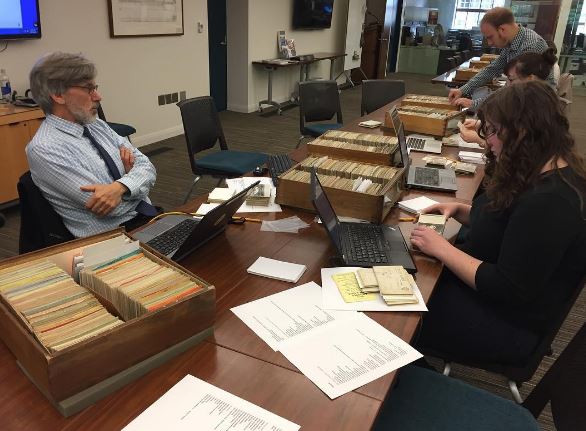

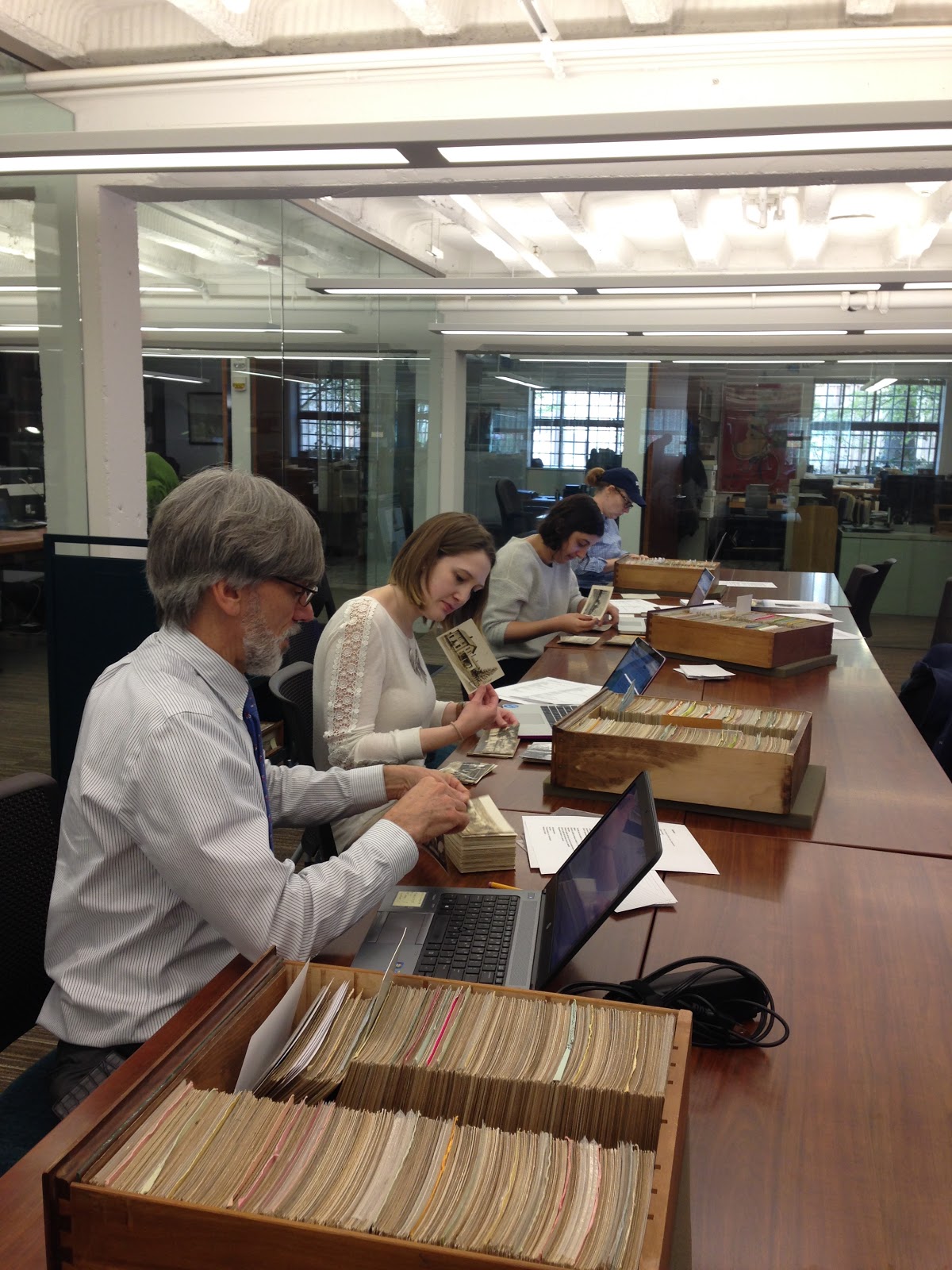

On the mornings of November 14th and November 18th, the University of Michigan’s Society of American Archivists (SAA) Student Chapter and the William L. Clements Library organized a two-part Archives Blitz. These events are held by the Student Chapter once or twice a semester. Since the fall of 2014, Student Chapter Archives Blitzes have ranged from several hours to week-long engagements with organizations. Organizations identify projects that they would like assistance with and that they think will be interesting, fun, and professionally engaging for students. Students are oriented and provided with staff feedback throughout the project.

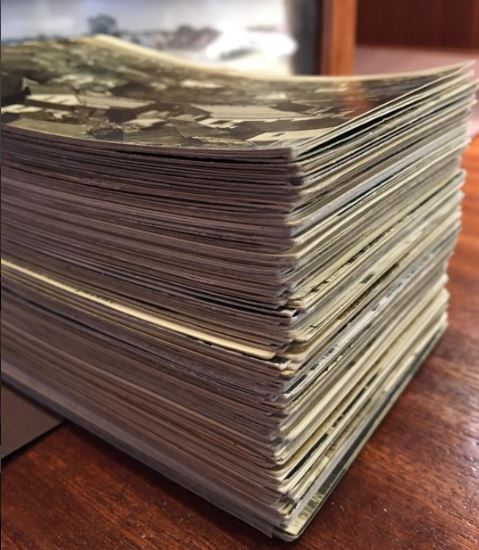

When SAA presented this event structure to the Clements Library, Clayton Lewis, curator of Graphics Material, jumped on the opportunity to have students dive into a collection of photographic postcards — approximately 55,000+ items. These photographs are a subset of the

David V. Tinder Collection of Michigan Photography, which consists of over 100,000 images of varying photographic types spanning the 1840s to the 1970s.

Pre-photographic postcard history

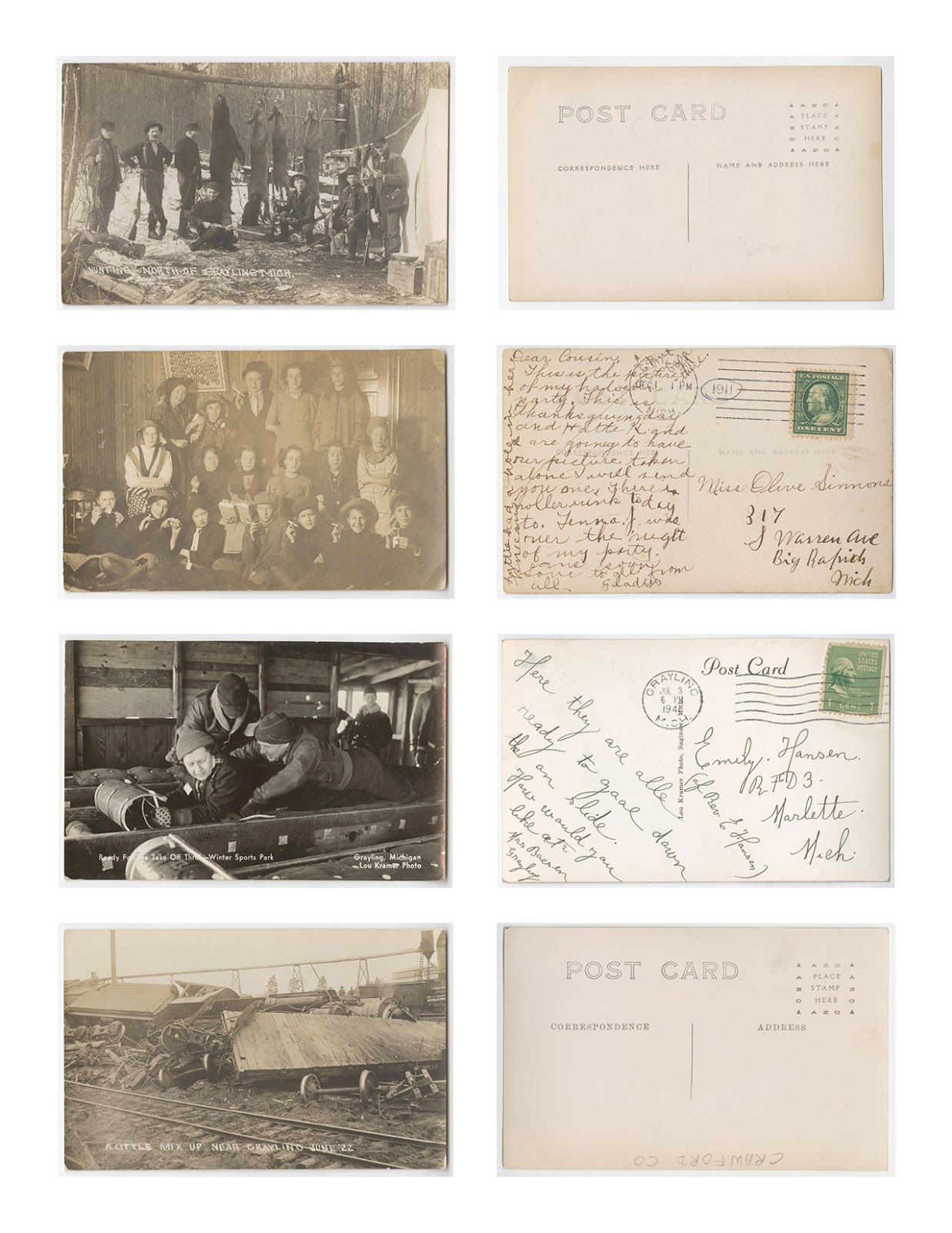

In an online exhibit, the Smithsonian Institution Archives identifies key periods in postcard history. Four of these periods, the “Pre-Postcard Period: 1848-1870,” “Pioneer Period: 1870-1898,” “Private Mailing Card Period: 1898-1901,” and “Post Card Period: 1901-1907” strongly shaped photographic postcards.[1] These periods are marked by acts of US Congress, establishing the rights of private postcard creators and the government to send postcards through the mail.[2] They are also marked by changes in the placement and allocation of message space.[3] The traditional structure of postcards with the address on one side of the postcard and the image and message on the opposite side of the postcard did not become the format we know today until 1907.[4] By 1907, the start of the Tinder photographic post-card collection, both private and government postcards could include messages on the address side of postcards.[5]

American real photographic postcards

By the turn of the century, photographic studios had sprung up in towns throughout the United States. These studios allowed professionals and amateurs to develop photographs and edition photographic postcard prints. Editions ranged in scope from one print to several hundred.[6] Rosamond B. Vaule states in “As We Were: American Photographic Postcards, 1905-1930” that these “diverse and intimate yet public images blur the lines between professional and amateur photographers.”[7] The accessibility local studios provided to all photographers is reflected in the subject matter of the photographic postcards that includes studio portraits, group photos of sports teams and school classes, town streets, workers, camps, railroads, events (like accidents or parades), factories, and landscapes.

The photographic postcard process was internationally popular but was most popular in the United States between 1905 and the 1920s.[8] During this period, photographic postcards were developed as positive prints from glass plate or film negatives on sensitized photo stock, cut to size with pre-printed postcard backs.[9] Photographic postcards often termed “real photo postcards” or RPPC (Real Photographic Post Cards) owe their popularity in part to the prevalence of photo studios, affordability of photography merchandise, and the speed with which postcards could be delivered to neighboring towns.[10] Importantly, many photographic postcards were never delivered, instead, they were saved as keepsakes or exchanged amongst family and friends.[11] Collecting both printed and real photo postcards in albums quickly became popular.

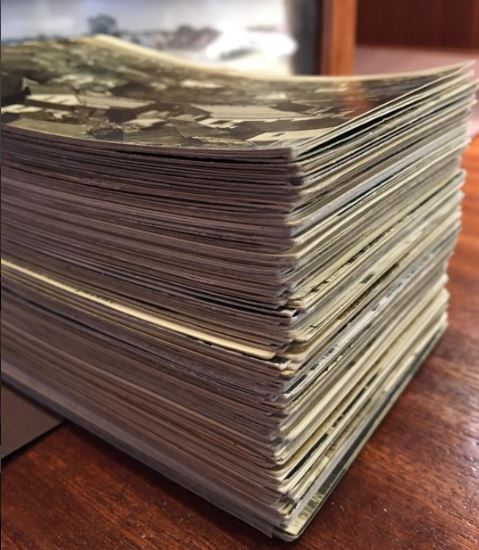

David Tinder was an avid collector of photographic post-cards of Michigan communities. His collection ranges in date from 1907 – 1960 but consists predominantly of black and white photographic postcards taken between 1905-1930. He organized the 55,000+ collection by counties and towns/placenames in an antique file cabinet. The Clements received the collection as 30 drawers from the cabinet, donated by Clements Library Associates member David Walters, in honor of his parents, Harold L. Walters, University of Michigan class of 1947, Engineering, and Marilyn S. Walters, University of Michigan class of 1950, LSA. Each tray contains roughly between 1,900 and 2,100 photographic postcards.

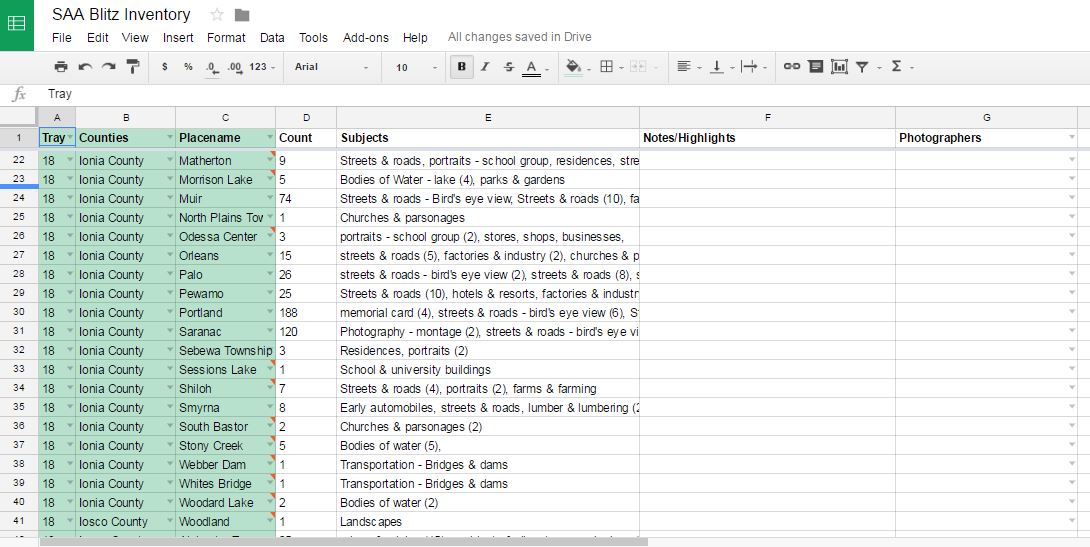

To prepare for the Blitz, Clayton and I met to discuss his overall vision for processing the collection and to identify the goals of the Blitz. Generally, the Clements processing sequence includes inventory, appraisal, accession, organization, conservation, rehousing, cataloging, and digitization. Since the collection had only been cursorily reviewed, we positioned it squarely within the inventory stage of processing. This inventorying stage would at the very least involve documenting Tinder’s county and town divisions as well as counting the photographic postcards within each county. While we knew this information would be fundamental, we also wanted to gather descriptive information about the subject matter in each county or town that could be used in a future finding aid. A decision on what form this descriptive information would take took several weeks to develop.

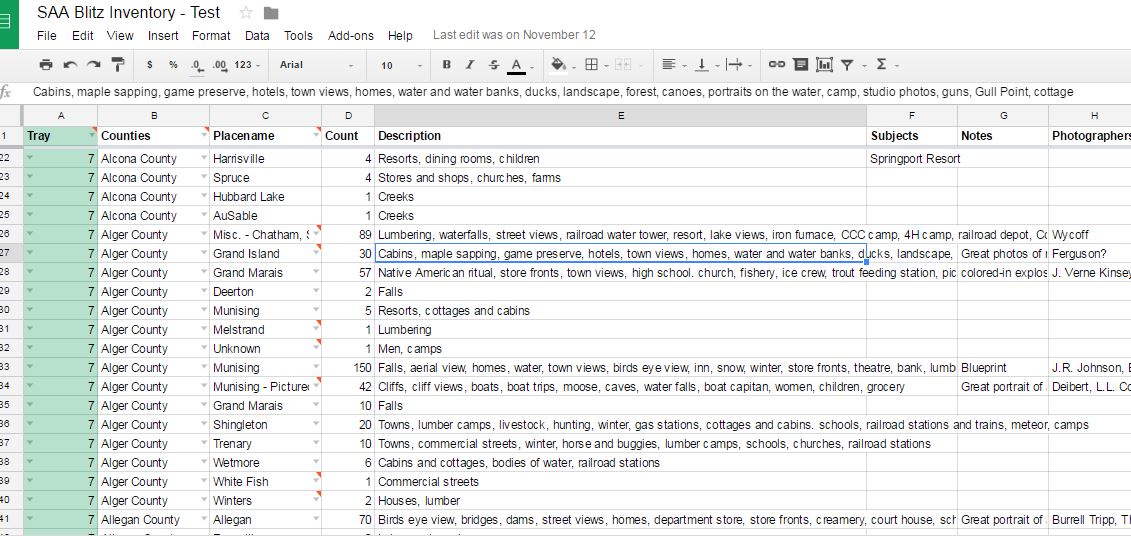

We designed three spreadsheets and four variations of controlled vocabularies before landing on a process for simultaneously inventorying and describing the collection that we were happy with. Our first spreadsheet captured descriptive information as a free-text subject list. We performed a quick test working as a pair and then conducted the same process alone. In pairs, one person counted and described the subject matter of the collection as one to three word subjects while the other recorded the information in the spreadsheet. We discovered that this process was faster alone although we calculated that it would take 4 hours to inventory and describe an entire drawer. Through this test, we also realized that there were unmarked transitions in the trays to different placenames.

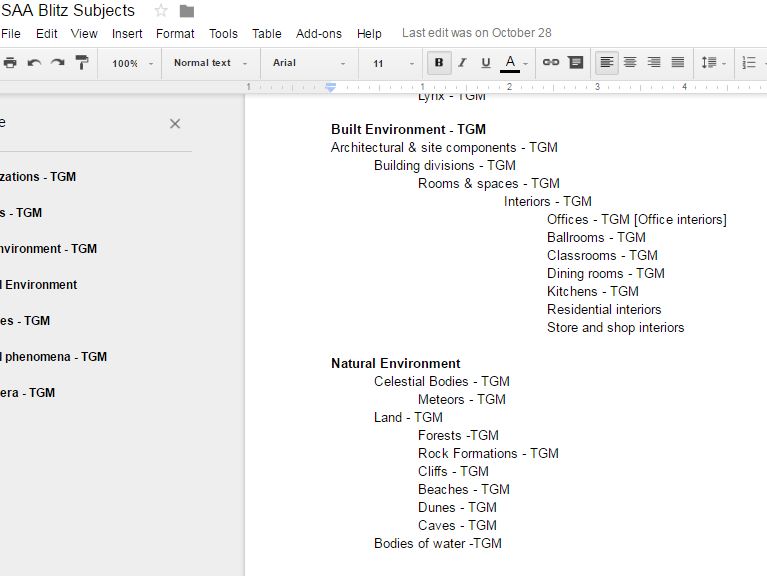

Looking across the tests at the variety and inconsistency in subject description, we attempted to create a controlled vocabulary that might serve as a helpful reference for students. The test helped us get a general sense of subjects in the collection from which we were able to abstract broader themes and terms. Our first attempt at a subject list amounted to a little under 200 subjects drawn from the list and from terms and hierarchies in the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names, the Library of Congress Subject Headings, the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus, and the Library of Congress Thesaurus for Graphic Materials. In this first iteration, we found our subjects grouping into subjects that described actions, objects, events, descriptions of people and organizations, and art historical/photographic genre types like still lifes, group portraits, and scenic views.

After two rounds of attempting to narrow down the subject list, we decided to use appraisal, the next stage in processing the collection, as a guide to both narrow and define the purpose of the subject list. For appraisal, Clayton would want broad subjects that described the contents of postcards in each county as well as specific subjects that would describe areas of interest to an appraiser. We created two lists, one for broad description of the postcards in each county that we called the “Main subjects” and limited to a page and one for subjects that we knew would be of interest to an appraiser based on the medium and the history of Michigan. We called this list “Special subjects”. In thinking about what might be lost using these lists, we realized that we also wanted to allow for qualification of the subjects and the highlighting of any photographic postcards that were particularly interesting. We added a list of “Qualifiers” which could be built upon by students during the Blitz as well as a ‘Notes” field that would allow students to note collection gems.

We created a two page subject list of “Main Subjects,” “Special Subjects,” and “Qualifiers” as well as a new spreadsheet. While we tried to respect the thesauri and subject headings we started with, we ultimately veered towards local subjects and variations on thesauri or subject headings that suited our needs for this stage.

Clayton was able to order the “Main Subjects” by the order in which David Tinder tended to organize the photographic postcards within counties.

Keywords

Main Subjects (in likely order of appearance)

Cities & towns

Streets & roads

Stores, shops, businesses

Municipal buildings

Civic infrastructure

Churches & parsonages

School and university buildings

Parks & gardens

Cemeteries

Monuments & memorials

Residences

Hotels & resorts

Entertainment

Restaurants

Events (qualify with event type i.e. fairs, processions, special events)

Misc. buildings

Farms & farming

Factories & industry

Mines & mining

Lumber & lumbering

Bodies of water

Construction & demolitions

Accidents & disasters

Clubs & organizations

Portraits (can be qualified i.e. “- group”)

Military

Students (qualify with type of student i.e. “- college”)

Musicians

Workers (qualify with type of worker from special subjects i.e. “- women workers”)

Sports (qualify with particular sport (i.e. baseball)

Recreation & leisure (i.e. picnics)

Advertisements

Animals

Transportation (i.e. air transport)

Boating & Boats

Aquatic activities

Outdoor activities (qualify with type of activity, i.e. hunting, fishing, camping)

Landscapes (Representations)

Maps

Manipulations

Special subjects (can be used independently or as a qualifier)

Holiday cards

Native Americans

African-Americans

Asian-Americans

Snow & snow removal

Railroads (qualify with “-depots”)

Steam boats

Early automobiles (i.e. wooden spoke automobiles)

Sanitariums and hospitals

Photography (Self-referential images of post-card shops, postcard photographers (self-portraits), the postcard process)

Auto industry

Lighthouses

Farm equipment (esp. Steam powered)

Qualifiers

elementary schools

middle schools

high schools

colleges and universities

cultural

women

men

children

construction

bird’s-eye views

interiors (can be qualified i.e. “- Stores & shops”)

The photographic postcard above from Bradley, Michigan, of a Native American baseball team is a good example of the kind of photographic postcard we would want to draw attention to with special subjects and qualifiers. Without these subjects and qualifiers, the photographic postcard would group with the subjects “Portraits” or “Sports,” indicating through distinct subjects that this is both a portrait and a photograph of something sports related. With the special subject “Native Americans” and flexible qualifiers, we can call attention to the fact that this postcard is a group portrait, a photograph of a baseball team, and a photograph of group or team of Native Americans, i.e. “Portraits – group – Native Americans” or “Sports – baseball – Native Americans.”

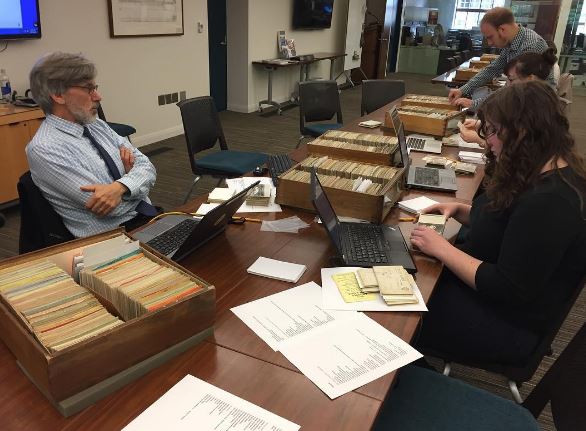

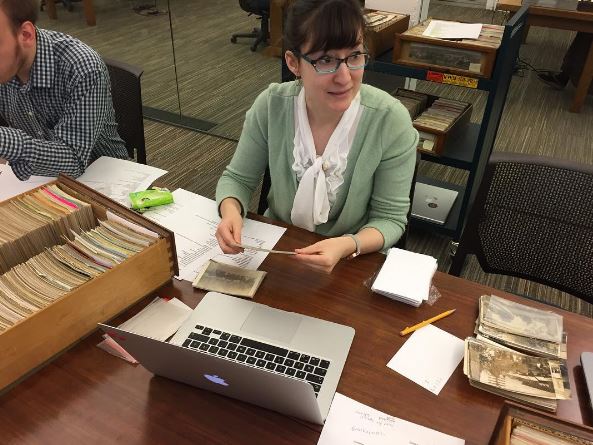

Our first Blitz went smoothly with students filling out the spreadsheet and adding new cards for the unmarked placenames.

|

| My photo, Day 1 |

|

| My photo, Day 1 |

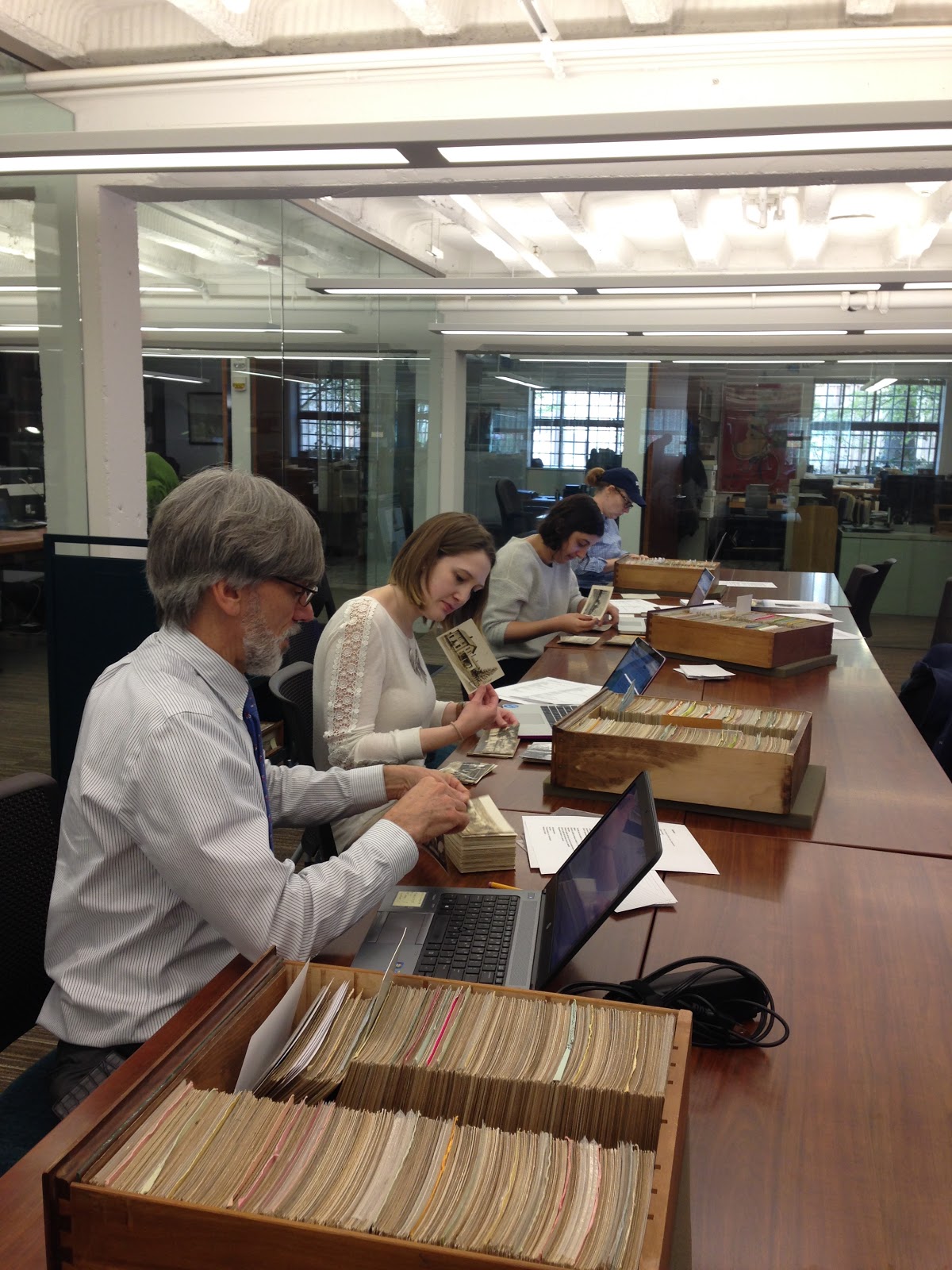

During the second session we realized that the subjects were less meaningful without concrete counts of the frequency with which particular subjects appeared. These counts were particularly significant for the “Special Subjects” we knew an appraiser would care about. After this realization, we included counts:

|

| Image credit: Yumi Taguchi photo, Day 2 |

While the subject list is imperfect, I am proud of the list we put together. We learned from this process that description for access and description for inventory and appraisal have different aims. Processing a project of this scale that is visual in nature is inherently challenging. As a voluminous collection with diverse subjects, there is detail that is lost in broad description that hampers user access. At the same time deep description of these postcards is no match for the photographic postcard itself. In his introduction to students, Clayton explained that the meaning and value of the collection for appraisal and intellectual control lies in groupings of items. Grouping items through shared subjects allows us to trace trends in the collection and ensures that subject groups that are unique can shine within the collection context.

The next stage in processing this collection after appraisal will be constructing a finding aid. The finding aid will likely translate some of the information we have collected into broad descriptive information. We’ve also discussed digitizing the photographic postcards in some kind of automated fashion similar to the Smithsonian’s

conveyor belt digitization.

Some of my favorite photos came from Grayling, Michigan. Within the Grayling County group there are a series of fabulous images of people partaking in winter sports at the “Winter Sports Park”.

I particularly enjoy the image of the group of young women dressed up for Halloween circa 1911 (second from the top). It’s also worth noting that most of these photographic postcards were never mailed!

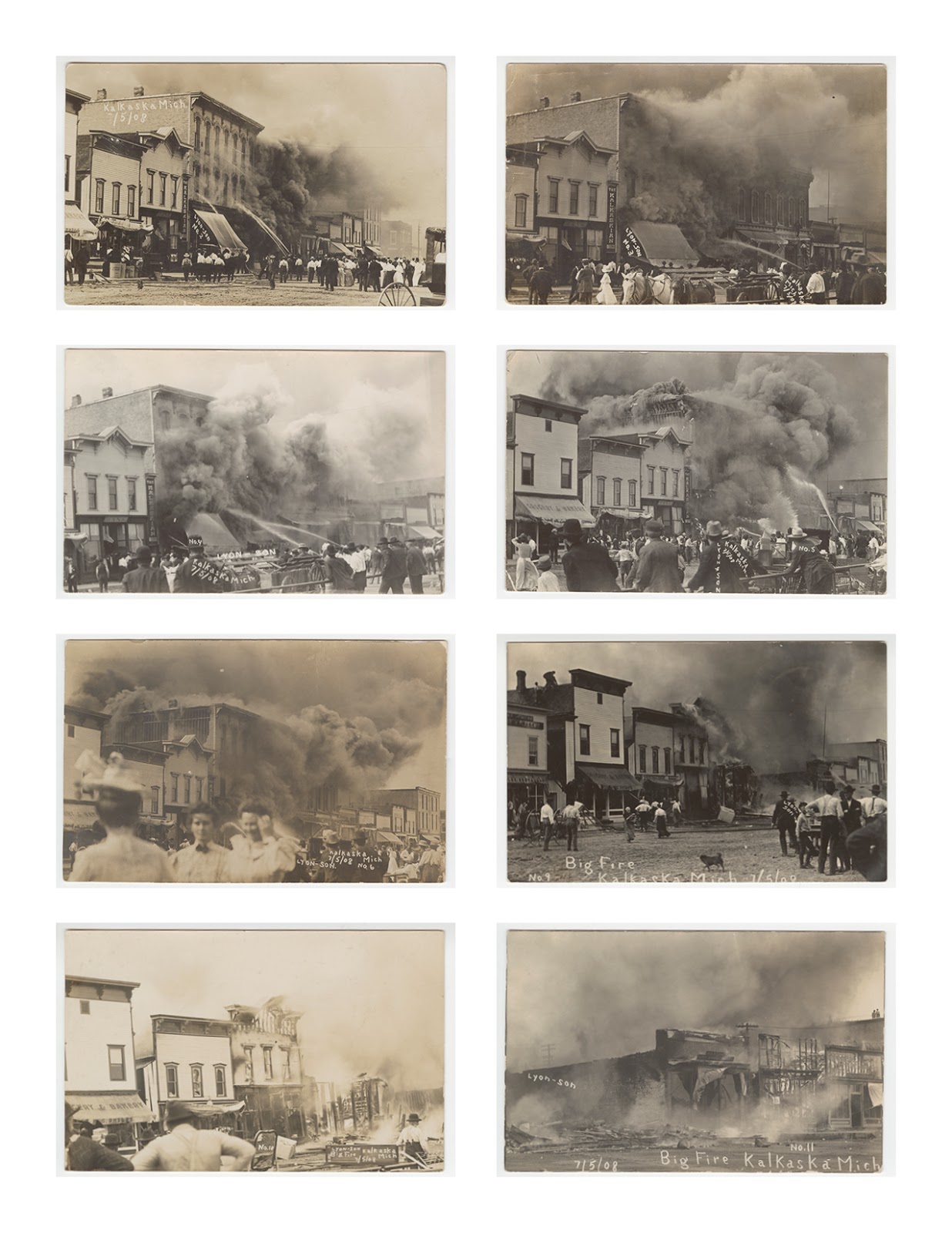

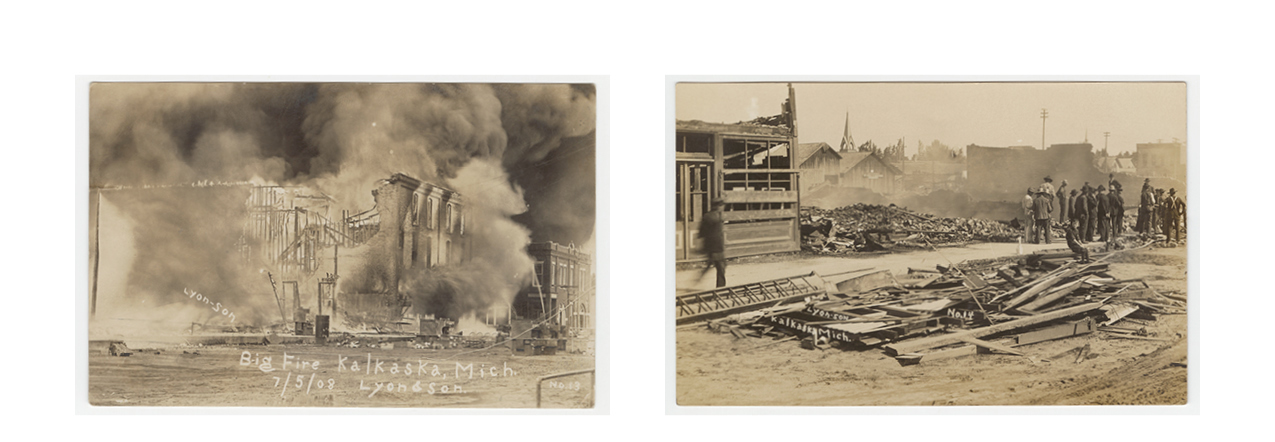

The following images depict a fire that took place on July 7th 1908. They are numbered and follow the fire through to its extinction.

The following two images are especially interesting. Whoever sent the postcards presumably marked the extent of the fire or shops that were destroyed.

Footnotes:

- “Greetings from the Smithsonian: Postcard History,” Smithsonian Institution Archives, n.d., http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/postcard/postcard-history.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Rosamond B. Vaule, As We Were: American Photographic Postcards, 1905-1930, 1st ed (Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, 2004), 9.

- Ibid., 19.

- Ibid., 21.

- Ibid., 21-22.

- Ibid., 48.

- Ibid., 62.

Bibliography:

1. “Greetings from the Smithsonian: Postcard History.” Smithsonian Institution Archives, n.d. http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/postcard/postcard-history.

2. Vaule, Rosamond B. As We Were: American Photographic Postcards, 1905-1930. 1st ed. Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher, 2004.

Monumental to be sure. Can it now be accessed online by the public?

Thanks for your interest in this collection. We are in the very early stages of processing this massive group of photographs. Our goal is to make it available online but it will be quite some time before we complete the cataloging, sorting, rehousing, and scanning needed to accomplish that. We are very grateful to the students who have volunteered to get the project off the ground. – Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphics Material.