Pair 18: The Bestseller List

Contents

Building on a Century of Collecting at the Clements Library

Pair 2: The Power of the Unseen

Pair 4: From the Big Picture to Individual Lives

Pair 5: Picturing African-American Identity

Pair 6: Leadership and Resistance

Pair 7: The Grid, Large and Small

Pair 8: Records of Self-Liberation

Pair 9: Death of Wolfe/Children’s book

Pair 10: Thomas Gage, from the Reading Room to the Digital World

Pair 11: Colonialism and Conversion

Pair 12: Documenting Disability

Pair 14: One Nation, Under a Grid

Pair 15: Judging Books by their Cover

Pair 16: Women Writers and Intellectuals

Pair 17: The Minds of Children

Pair 19: Sex and Gender in the Public Sphere

Pair 21: Organizing the Natural World

Pair 22: Collective Memories of Abraham Lincoln

Related Resources

Pair 18: The Bestseller List

What makes a book a “bestseller”? Simply selling a lot of copies isn’t enough. Even before the appearance of bestseller lists kept by newspapers and trade publications, people in the publishing trade in the United States understood that to be a bestseller, a book had to create a sensation. Even more than being read, a bestseller had to be a book that was talked about. And sales volume wasn’t enough—a bestseller had to sell fast.

There is a lot of debate over what the second-best selling bestsellers were in the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, but that’s because there’s no debate over what the top bestsellers were. No book printed in North America had sold like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense did when it was first printed in Philadelphia in January 1776. And no book since Common Sense had created the sensation that resulted from the 1852 publication of the book version of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

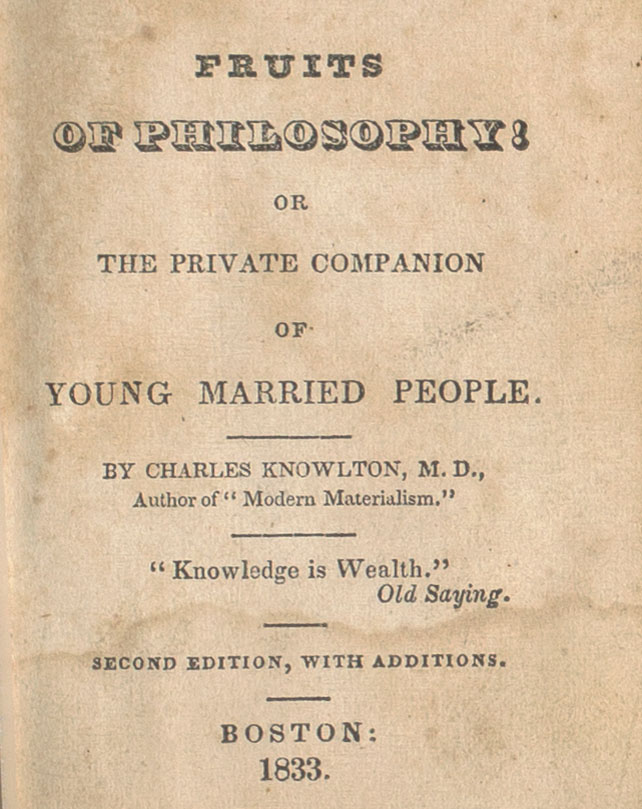

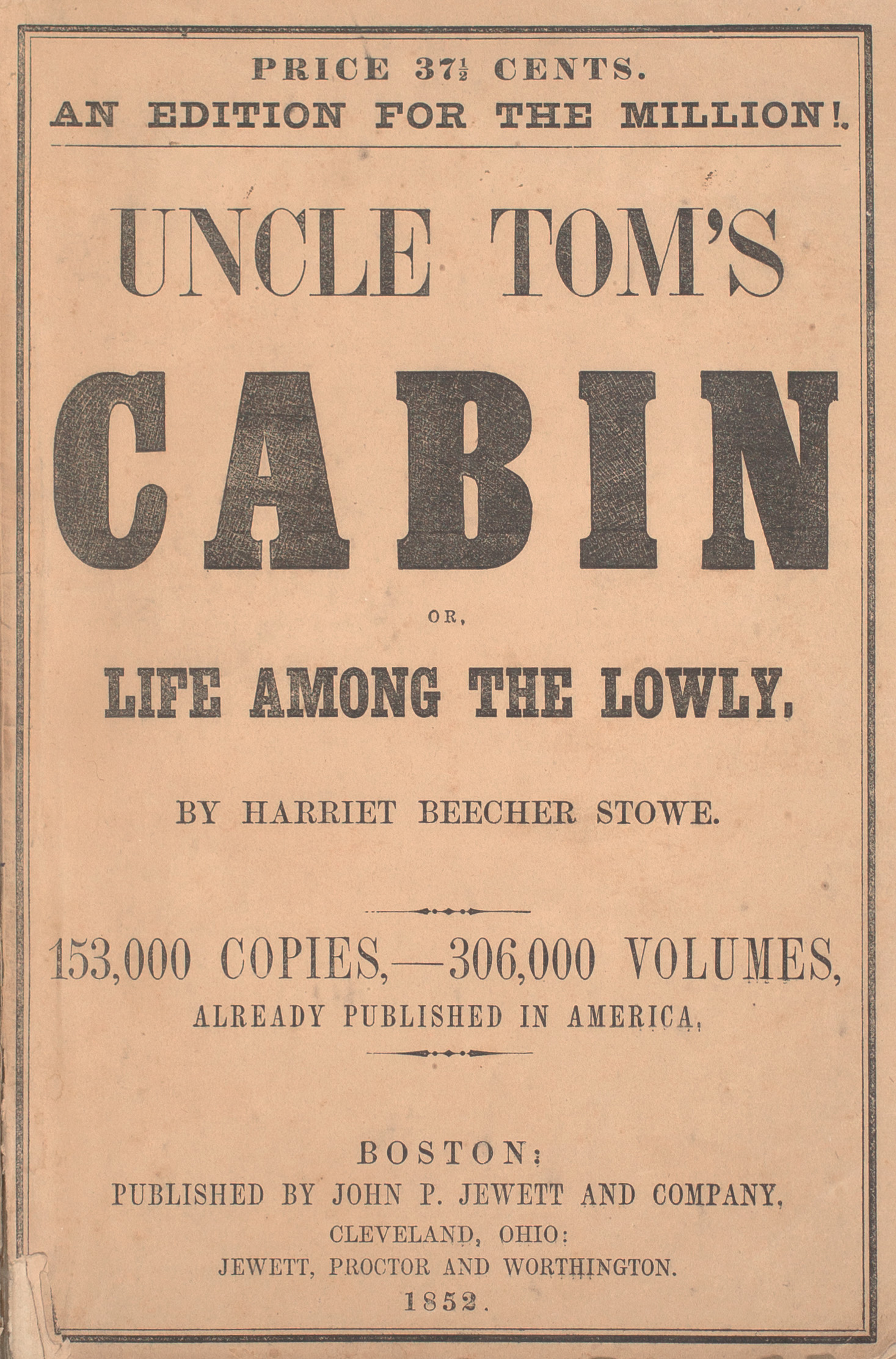

Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life Among the Lowly (Boston & Cleveland: John P. Jewett & Col, 1852), original printed wrappers.

[purchased from McBride Rare Books in Sept. 2022]

It’s hard to grasp today how many copies of Common Sense were in circulation in 1776. 120,000 copies were sold in the book’s first three months on the market; by the end of the Revolutionary War, over 500,000 copies were in circulation. It is estimated that twenty percent of American colonists owned a copy of Common Sense.

75 years later, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote a very different kind of bestseller. While Common Sense is a bluntly forceful political polemic, usually in the neighborhood of 50-70 pages, Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a sprawling novel of well over 500 pages that makes a deeply emotional appeal against slavery. After first appearing in over 40 serial installments in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era in 1851-52, Stowe’s novel was published in book form in late March of 1852, and it sold like nothing since Paine’s pamphlet. 10,000 copies of Uncle Tom’s Cabin sold in its first week of publication in the U.S., and 300,000 copies in its first year. The novel was a sensation on both sides of the Atlantic, with 1.5 million copies flying off the shelves in Great Britain in its first year.

The Clements Library’s collections bear evidence of both titles’ spectacular success. The Clements holds over twenty editions of Common Sense from 1776 alone, printed on both sides of the Atlantic. Editions came out so rapidly that it is almost impossible to identify the order in which they appeared. Pictured here are the first Philadelphia edition and one of the countless later editions from 1776—when the Newport edition appeared is almost impossible to say, and it looks extremely similar to the Philadelphia edition. We hold fewer editions of the full-length novel of Uncle Tom’s Cabin—around ten, along with numerous dramatized versions and songs inspired by the novel. The mid-19th-century publishing industry offered more options for readers who wanted to buy Stowe’s novel. In 1852 they would have been able to choose from three different bindings, and the variety would only increase from there. Pictured here is an 1852 edition acquired in 2022 bound in its original paper wrappers, the least expensive binding option among many that Stowe’s Boston-based publisher John Jewett produced. The variety in available versions would increasingly come to include pirated editions. The second copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin pictured here was printed in Halifax, UK, also in 1852. The proliferation of pirated editions such as this testify to the novel’s bestseller status.