Pair 20: We Are What We Ate

Contents

Building on a Century of Collecting at the Clements Library

Pair 2: The Power of the Unseen

Pair 4: From the Big Picture to Individual Lives

Pair 5: Picturing African-American Identity

Pair 6: Leadership and Resistance

Pair 7: The Grid, Large and Small

Pair 8: Records of Self-Liberation

Pair 9: Death of Wolfe/Children’s book

Pair 10: Thomas Gage, from the Reading Room to the Digital World

Pair 11: Colonialism and Conversion

Pair 12: Documenting Disability

Pair 14: One Nation, Under a Grid

Pair 15: Judging Books by their Cover

Pair 16: Women Writers and Intellectuals

Pair 17: The Minds of Children

Pair 19: Sex and Gender in the Public Sphere

Pair 21: Organizing the Natural World

Pair 22: Collective Memories of Abraham Lincoln

Related Resources

Pair 20: We Are What We Ate

Early American cookery books provide a window into the historic kitchens, pharmacies, and laboratories where a wide variety of culinary and medical recipes were formulated. Household recipe books often include entries for delicious dishes printed adjacent to formulas for chemical cleaning supplies or medical remedies, which can be a delightful surprise for the modern reader anticipating pristinely organized lists of appetizers, entrees, and the like.

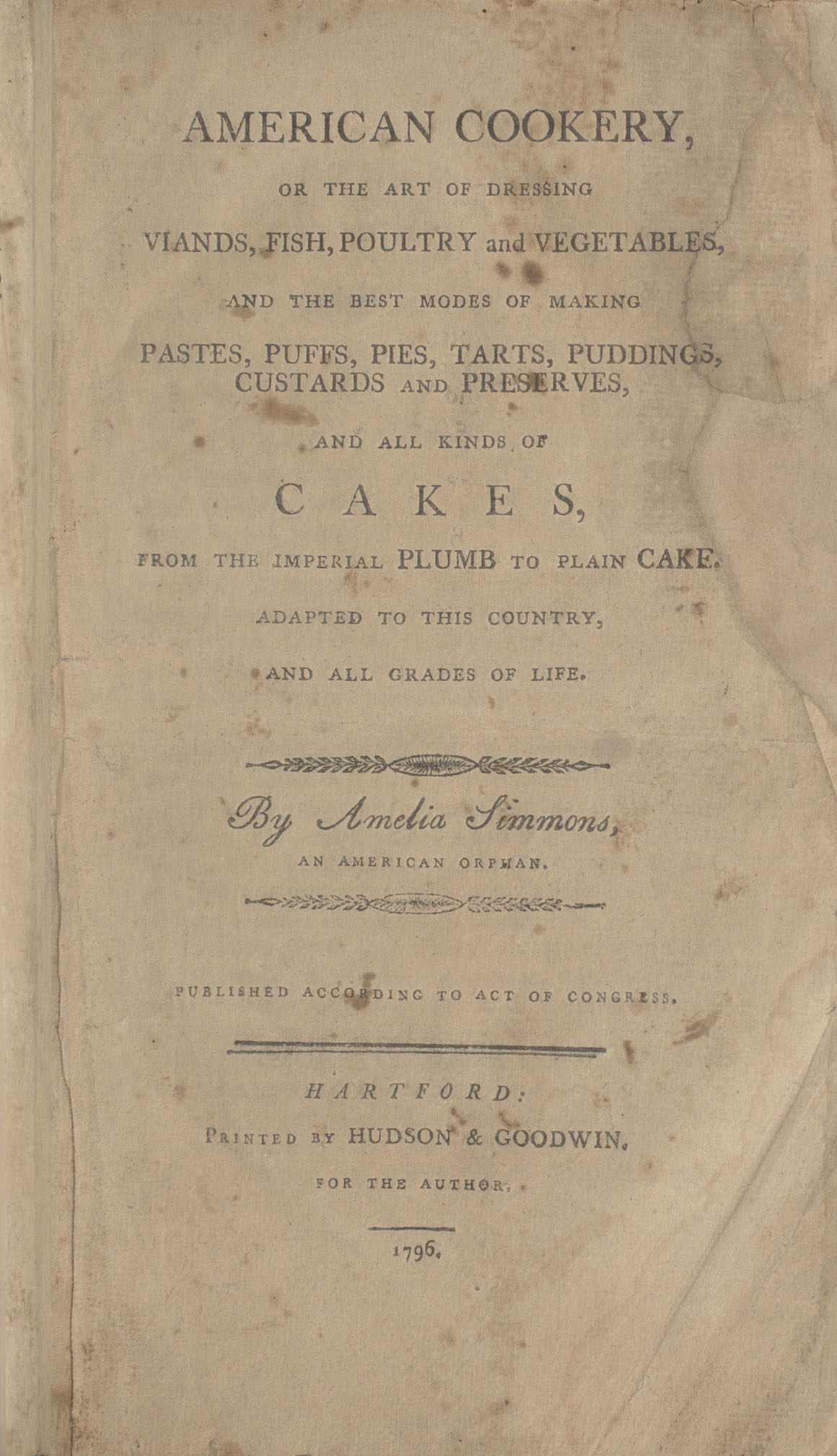

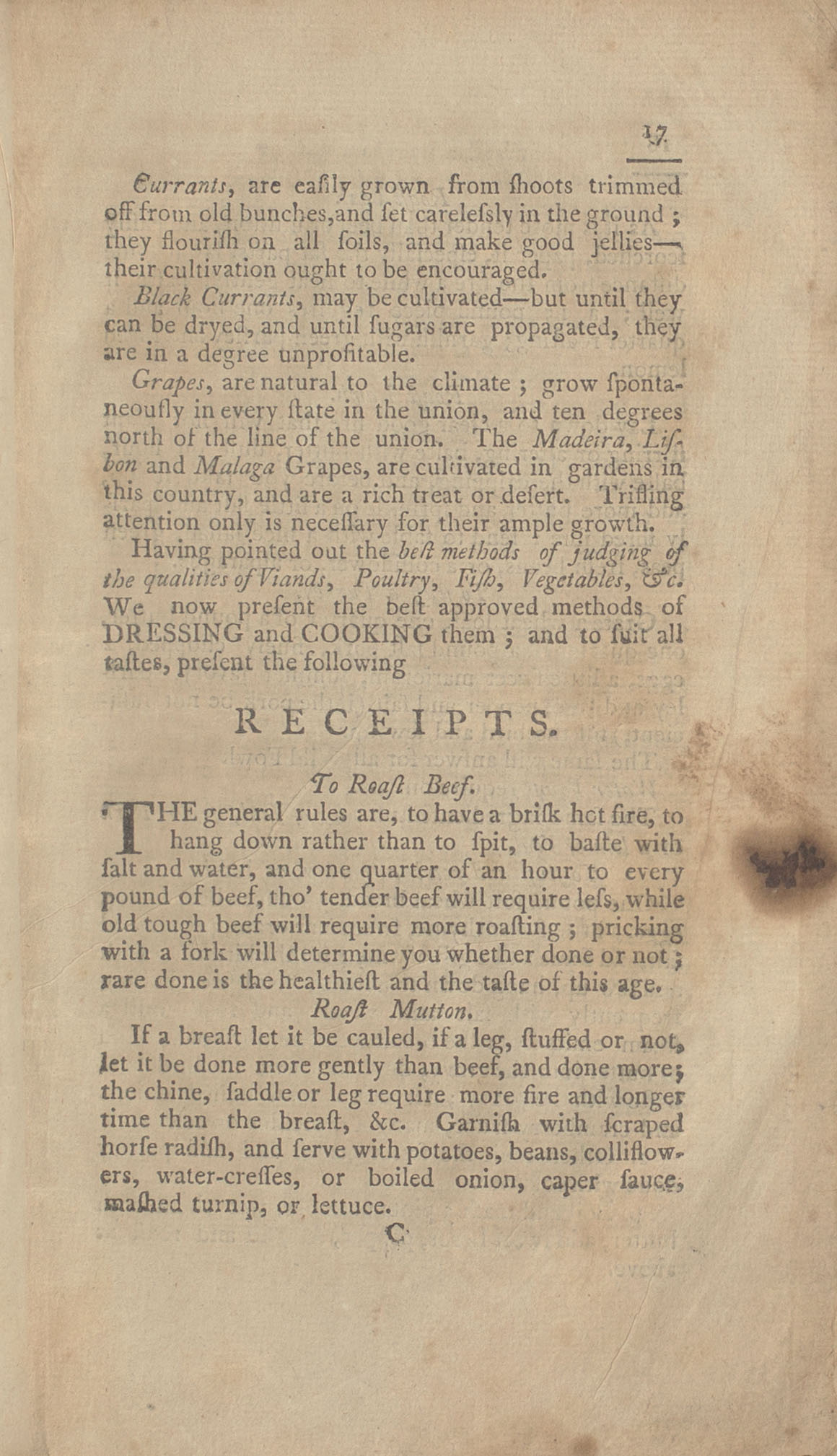

In 101 Treasures, Amelia Simmons’ American Cookery (Hartford, 1796) featured as the first printed cookbook specifically tailored for American cuisine. Simmons was renowned for her unusually original recipes featuring indigenous products. Whether pairing New World specialties such as cranberry sauce and roast turkey, or printing – for the first time – recipes for Johnny Cake, Indian Pudding, and cornmeal, Simmons developed recipes that would become staples in the colonial American household. American Cookery’s most impactful contribution for bakers everywhere was Simmons’ recipe for Pearlash, a chemical leavening agent for doughs which laid the foundation for the future compounding of modern baking powders.

Amelia Simmons, American Cookery

Hartford: Printed by Hudson & Goodwin for the author, 1796.

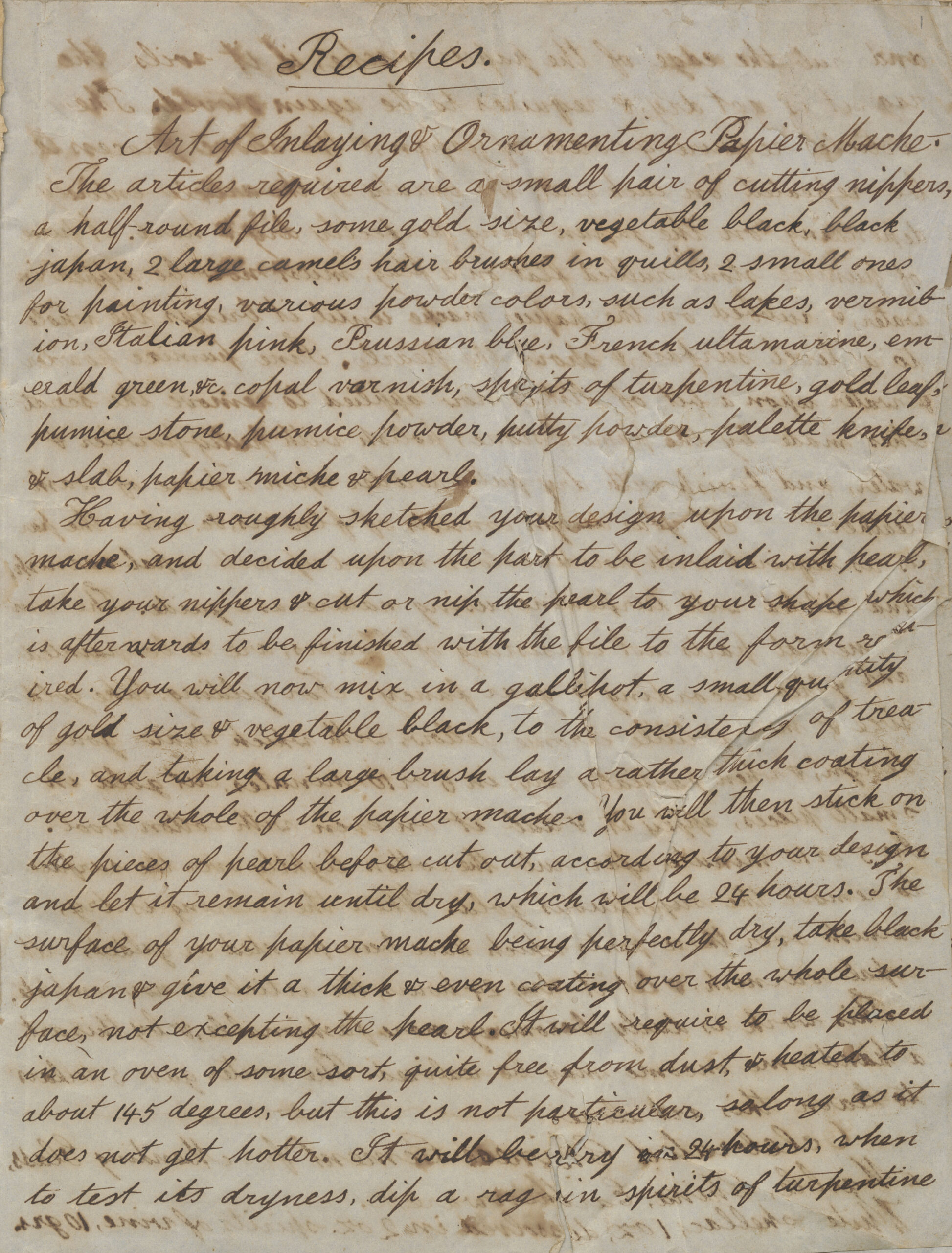

In addition to culinary print landmarks such as American Cookery, manuscripts such as the anonymously compiled “Practical and Medicinal Recipes manuscript ([1860s?])” provide insight into how individual people assembled their own handwritten collections of recipes. “Practical and Medicinal Recipes” is covered with a wrapper made from wallpaper and offers 18 pages of recipes for everything from hair-loss preventatives to pimple cures to “Turkish Rouge to give a Beautiful Complexion.” Contents span the gamut from tangible product to methodological instruction; advice for engraving music sheets and ornamenting papier mache accompanies inventive recipes for “New Hydrographic Paper,” a formulation on which the author only needs “a sharpened stick and water, or indeed saliva” in order to write. Although the compiler is anonymous and the purpose of the volume is not explicitly stated, several entries produce significantly large quantities of product, and some note the likelihood of potential sales at market. The attention to raw materials and revenue suggests that the compiler may (or may not) have been a manufacturer or wholesaler.

Together, the volumes represent the generic dynamism of recipe books, which immerse their readers in the daily rituals of domestic and commercial life in early America.

“Practical and Medicinal Recipes manuscript ([1860s?])