Funerals

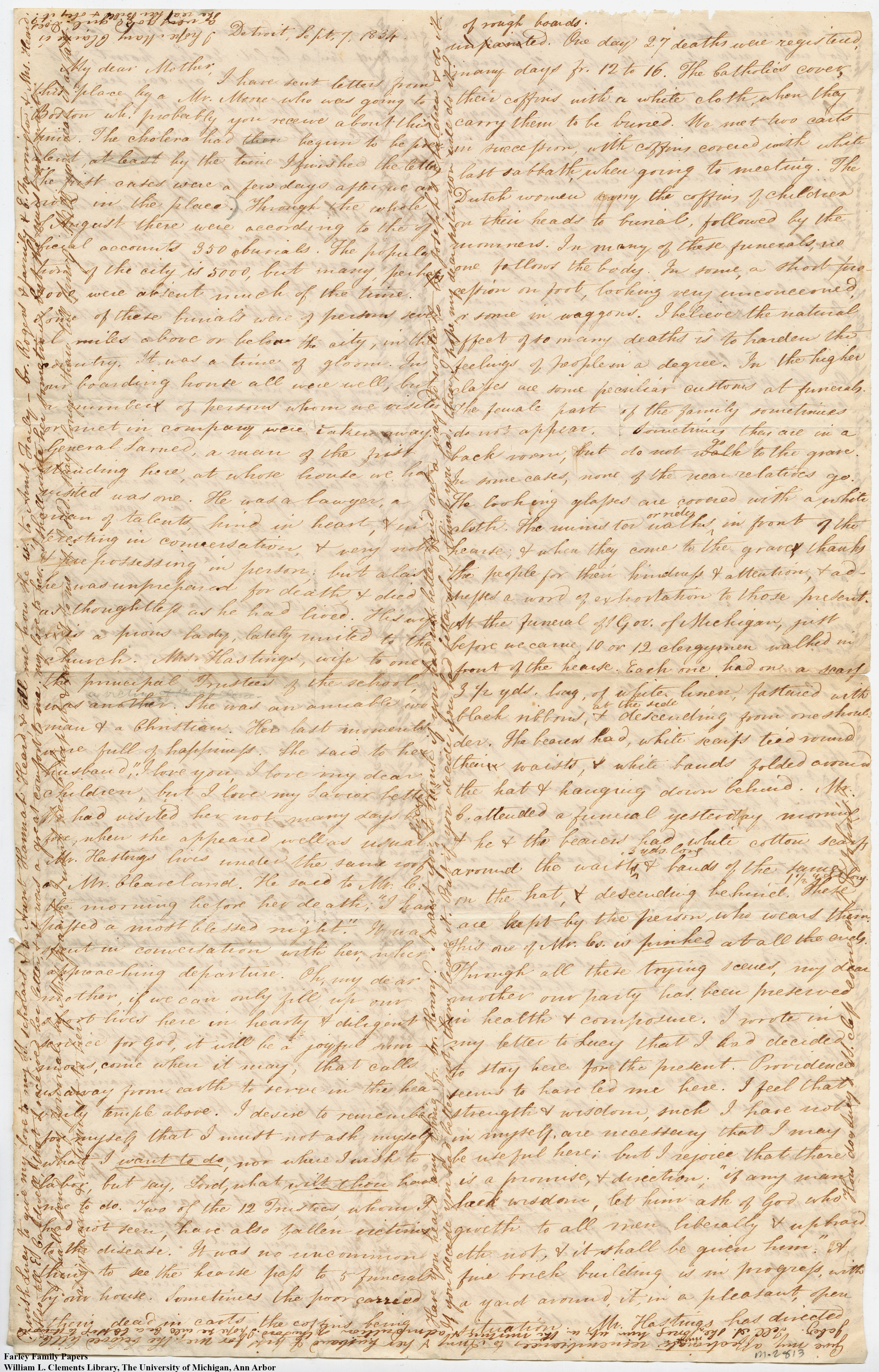

Susan Farley to her mother, Detroit: September 7, 1834. Farley Family Papers.

Susan Farley visited Detroit, Michigan Territory in 1834. While there, she witnessed a cholera epidemic that took the lives of several hundred people. Her description includes details on the clothing of mourners, the order of processions, and the impact of mass funerals on the populace.

“I have sent letters from this place by a Mr. Moore who was going to Boston wh. probably you receive about this time. The cholera had then begun to be prevalent, at least by the time I finished the letter. The first cases were a few days after we arrived in the place. Through the whole of August there were according to the official accounts 350 burials. The population of the city is 5000, but many, perhaps 2000 were absent much of the time. Some of these burials were of persons several miles above or below the city, in the country … It was no uncommon thing to see the hearse pass to 5 funerals by our house. Sometimes the poor carried their dead in carts, the coffins being of rough boards. One day 27 deaths were registered, many days from 12 to 16. The Catholics cover their coffins with a white cloth, when they carry them to be buried. We met two carts in succession, with coffins covered in white last sabbath, when going to meeting. The Dutch women carry the coffin of children on their heads to burial, followed by the mourners. In many of these funerals, no one follows the body. In some, a short procession on foot, looking very unconcerned or some in wagons. I believe the natural effect of so many deaths is to harden the feelings of people in a degree. In the higher classes are some peculiar customs at funerals. The female part of the family sometimes do not appear. Sometimes they are in a back room, but do not go to the grave. In some cases, none of the near relatives go. The looking glasses are covered with a white cloth. The minister walks or rides in front of the hearse; & when they come to the grave, thanks to the people for their kindness and attention, & addresses a word of exhortation to those present. At the funeral of Gov. of Michigan [George Bryan Porter], just before we came 10 or 12 clergymen walked in front of the hearse. Each one had on a scarf 3 ½ yds long, of white linen, fastened with black ribbons as the side, & descending from one shoulder. The bearers had white scarfs tied around their waists, & white bands folded around the hat & hanging down behind. Mr. C. attended a funeral yesterday morning & he & the bearers had white cotton scarfs around the waists 3 yds. long & bands of the same on the hat, & descending behind. These are kept by the person who wears them. This one of Mr. C.’s is pinked at all the ends.”

Edward Fenno to Maria Hoffman, New Orleans: January 23, 1819. Fenno-Hoffman Family Papers.

In this letter, Edward Fenno describes a New Orleans funeral and burial. His commentary suggests the significance of geography and climate to burial services. The grave was filled with water and, unable to sink the coffin, the grave digger resorted to drastic measures.

“I saw yesterday a funeral, which entered the gates while Martin and I were strolling in the grave yard. It was preceded by several Catholick priests, dressed very fantastically and bearing in their hands crucifixes, tapers, &c. while approaching the hole, for it cannot be called a grave, they were chaunting requiems for the departed soul, and after murmuring a prayer or two immediately walked away, leaving the negro grave digger to finish the job, as it really was. The grave was filled with water and the old negro jumped on the coffin to sink it, but did not succeed, attempts were then made by other negros to sink one end at a time but it would not do, after working about ten minutes one of them beat a hole in the end of the coffin with a spade, and by pressing it down until the water filled it, finally succeeded in sinking it; The grave digger continued to stand on it, and with a large hoe raked in the mud, bones, skulls and every other remnant of mortality which he had dug out. I never before witnessed so shocking and brutal a spectacle and was as astonished at the want of feeling, evinced by the female relatives, who stood by until it all was over. There were at the time more than thirty large and several children’s graves ready dug and waiting for victims. This place is almost enough to deter one from remaining, but I have seen so many strange sights here, that this has lost much of its natural horror by comparison. The city is now very healthy, or old Death would not have so many graves ready.”

Lyman Hobbs to Daniel Hobbs, New Orleans: November 10, 1833. American Science and Medicine Collection.

Hobbs’ letter to his father indicates the significance of class and wealth during a New Orleans epidemic. The cost of burials forces slaves and the poor to accept interment in the “waste lands” around the city.

“Most accounts in northern papers were probably individual reports and greatly exaggerated, while on the other hand, the papers of this place, strained the truth equally hard the other way, as they only gave the number of interments in 2 of the burying grounds, while there are four in the limits of the city & the expence of interment in any of them is what would be considered in your part of the country, very great, and indeed it is great, in any place, for the poor class. For a grown person $6- for interment. For a hearse (in sickly times) $10- and for coffin as much more. Many slaves, whose masters were unwilling, and many whites whose friends were unable, were buried in the open waste lands that surround the city. I would not be understood that all are excluded who can not pay for interment – there is provision made for burying the poor at the expence of the corporation, but at the death of a wif or husband, parent or child, is an untimely moment to tantallize the feelings of survivers of the honest, industrious family.”