George Washington and Abraham Lincoln

Left: John J. Barralet, Commemoration of Washington, hand-colored engraving: [ca. 1816?].

In this commemorative print, Barralet used traditional symbolic imagery to express George Washington’s apotheosis, his rise to divinity. In the lower right hand corner is an early European allegorical representation of America, a Native American. To his left are Liberty, standing with arms representing Washington’s military service; the American eagle; and faith, hope, and charity. These figures mourn Washington, who is raised from his tomb by the spiritual and temporal Genius and Father Time.

Right: D. T. Weist, In Memory of Abraham Lincoln: the Reward of the Just, lithograph after John J. Barralet, Philadelphia: 1865.

D. T. Weist pirated John Barralet’s Commemoration of Washington print (above) in 1865 by re-creating it with Abraham Lincoln’s head atop Washington’s body and changing the inscription on the tomb. The symbolic imagery did not suit Lincoln as well as it did Washington, but this did not prevent the print from outselling Barralet’s original.

George Washington

On December 12, 1799, George Washington inspected his Mount Vernon plantation in heavy snowfall. He worked outdoors the next day, marking trees for cutting. His resulting sore throat, speech trouble, difficult breathing, and medical treatments ultimately proved fatal. Four physicians, armed with the best medical knowledge of the day, failed to improve his condition. They bled him, bathed him, and applied oral and topical medications. He died on December 14, 1799. The precise cause of his death is disputed, but modern analyses argue that he suffered from a form of acute epiglottitis (inflammation of the tissue around the trachea), exacerbated by the blood loss from his treatment.

In his last will and testament, George Washington ordered that his “Corpse may be Interred in a private manner, without parade, or funeral Oration.” Despite his wishes, Washington’s family permitted his Masonic lodge to prepare a funeral procession, which was held at Mount Vernon on December 18, 1799. The ceremonies ended with Washington’s burial in the family vault.

George Washington commanded the army that won the American Revolution and served as a figurehead and personal embodiment of the cause. He was the first President of the United States. The death of George Washington affected the American populace as no other public figure would until Abraham Lincoln’s death in 1865. Americans mourned the death of Washington with symbolic funerals held in numerous cities and towns. Many of these processions were complete with empty biers (portable stands for carrying a coffin or body), rider-less white horses, and eulogies. Washington was valorized and compared to great figures of the classical and Biblical world. Commemorative memorabilia reflected George Washington’s place as a symbol of national unity.

Tobias Lear, A Minute Account of the Last Sickness and Death of George Washington, Mount Vernon, Virginia: December 14, 1799. Tobias Lear Papers.

Tobias Lear was George Washington’s personal secretary from 1785 to 1799. One of the great treasures in the Clements Library is a lengthy letter by Lear, describing Washington’s last illness and death. This particular letter, one of several Lear wrote about the event, is the longest and finest eyewitness description of Washington’s death in existence. The arrow points to Washington’s last words.

The Washingtoniana, Baltimore: 1800.

The Washingtoniana provided readers with information about the life of George Washington immediately following his death. It includes a sketch of Washington’s life, funeral honors, commemorative orations and poetry, and his last will and testament. Publishers reprinted this work several times. The open pages show the order of George Washington’s funeral procession on December 18, 1799, at his Mount Vernon plantation.

Sacred Music, to be Performed in St. Paul’s Church, on Tuesday the 31st December, 1799, by the Anacreontic and Philharmonic Societies, [New York: 1799].

One symbolic funeral procession for George Washington took place in New York City on December 31, 1799. This procession included music by the Anacreontic and Philharmonic societies. The words to their music are on a black-bordered broadside, printed for the occasion.

Samuel Holyoke, Hark! From the Tombs, &c., and Beneath the Honors, &c., Exeter, New Hampshire: 1800.

In Samuel Holyoke’s Hark! From the Tombs, he reflects on death as the common fate of mankind and then, in Beneath the Honors, he laments the departed George Washington.

From Beneath the Honors:

“Ye gentlest ministers of Fate, Watch where our Nation’s Saviour lies, And bid the softest slumbers wait, With silken cords to bind his eyes, Rest his dear sword beneath his head; Round him his faithful arms shall stand; Fix his bright ensigns on his bed, The guards and honors of our land … Night and the grave, remove your gloom; Darkness becomes the vulgar dead; But Glory bids the Hero’s tomb Disdain the horrors of shade. Glory with all her lamps shall burn, And watch the Warrior’s sleeping clay, Till the last trumpet rouse his urn To aid the triumphs of the day.”

Tomb of Washington, engraving by G. Murray, drawn by G. Fairman from a sketch by W. Bawle: ca. 1810.

George Washington’s last will and testament stipulated that the existing family vault, “requiring repairs, and being improperly situated,” should be replaced by a new one. These wishes were only realized after a vandal broke into the old vault. The Washingtons were moved to the new tomb in 1831.

Left: Francis Johnson, Centennial Dirge, Philadelphia: 1832.

Francis “Frank” Johnson, a successful African American career musician, wrote and published this Centennial Dirge in honor of the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s birth. Frank Johnson and his band traveled from Philadelphia with the Light Artillery Corps of Washington Grays to perform the piece at Mount Vernon. The cover illustration depicts the original Washington family vault.

Right: The Tomb of Washington, Mount Vernon, engraving by J. Cousen after W.H. Bartlett, London: 1838.

This engraving shows the Washingtons’ stately post-1831 tomb.

[Visitors at Washington’s tomb], ambrotype, Mount Vernon: ca. 1850s.

Travelers frequently visited Mount Vernon as tourists. One photographer distributed handbills to advertise his services before visitors reached the tomb. He exposed and processed the photosensitive plates on site making it possible for tourists to take home personalized memorabilia.

Left: Rev. Asahel Hooker, Sermon on the Death of George Washington, Goshen, Connecticut: January 1800. Washingtoniana Collection.

Sermon ending: “Finally, while we, this day, lament, saying my father, my father, the chariots of America, & the horsemen thereof, let all People unite, in fervent prayer, that the falling mantle of the departed Washington may light on the head of his successor in office, & a double portion of his spirit descend on all, who shall reside in the counsels of the nation, to the end of time.”

Right: Éloges Funèbres de Washington, Paris: 1835.

Funeral orations in honor of Washington were not restricted to America. This work contains a reprint of Louis Fontanes’ eulogy, delivered at “l’église de l’hôtel des Invalides” in Paris and a previously unpublished eulogy, written by Parisian bookseller J.F. Dubroca.

Abraham Lincoln

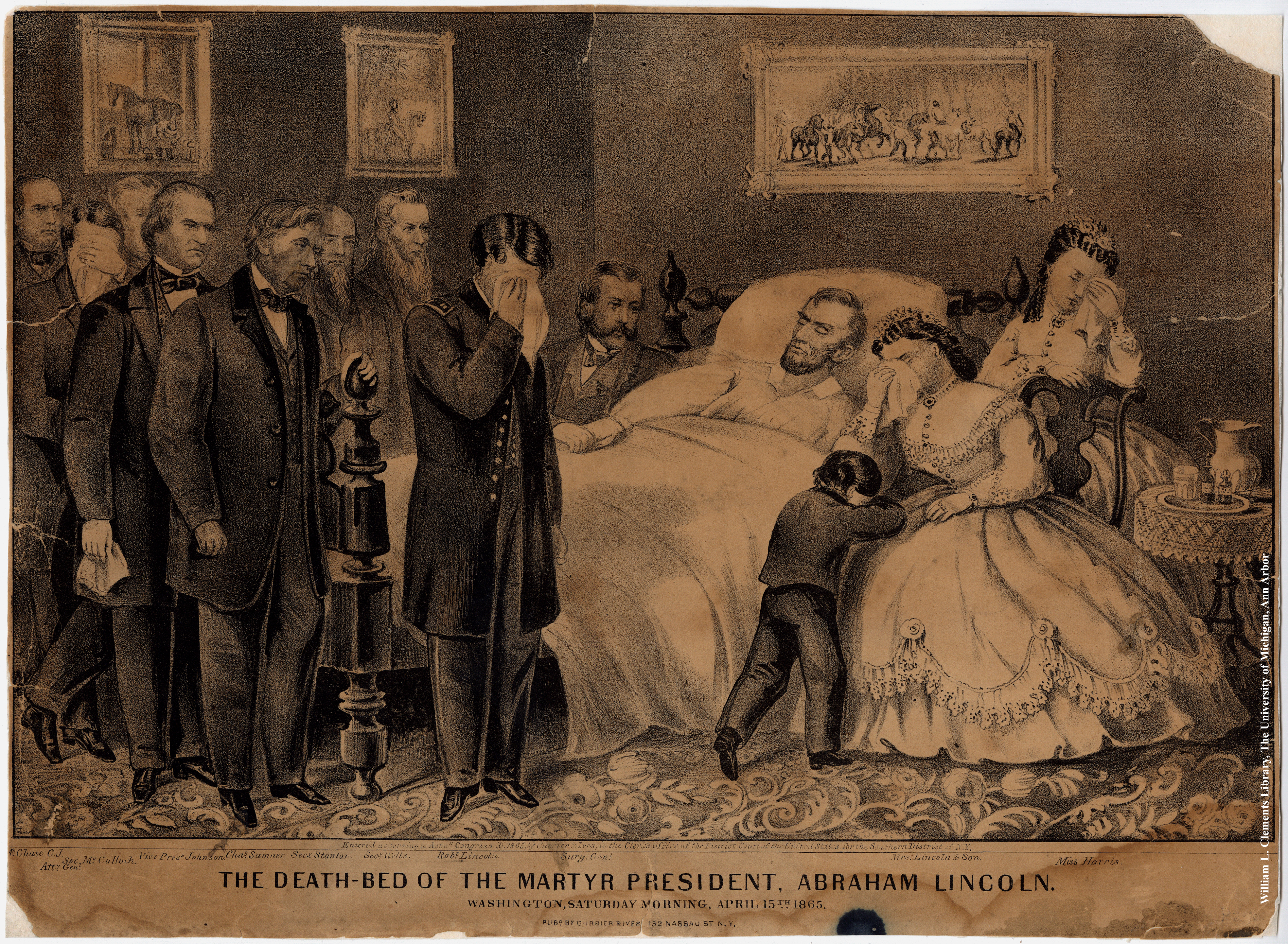

On April 14, 1865, five days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender, Abraham Lincoln attended a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. He sat in the presidential box with his wife Mary Todd, Major Henry Rathbone, and Clara Harris. During the play, John Wilkes Booth shot the President in the back of the head, leapt from the presidential box to the stage (breaking his leg in the process), and escaped on horseback. A physician in the theater, Dr. Charles Leale, examined President Lincoln and determined that he was mortally wounded. Lincoln was taken across the street to the boarding house of William Peterson and placed on a first-floor bed for the remaining nine hours of his life.

John Wilkes Booth and his co-conspirators intended to murder President Abraham Lincoln, Vice President Andrew Johnson, and Secretary of State William H. Seward. Only the Lincoln plot succeeded.

Dr. Charles Brown patented an embalming method to help transport the bodies of Civil War casualties. His work permitted hundreds of thousands of mourners and curiosity-seekers to view Lincoln’s body. The publicity stemming from Lincoln’s preservation improved American acceptance of the procedure.

The White House was decorated for mourning and visitors were permitted to view Lincoln’s body on April 18, 1865. The next day, invited attendees crowded into the East Room for the funeral services. Another public viewing followed. On April 21, Lincoln was placed on a funeral train for transport to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois. The President’s corpse had over 10 more public viewings in different states along the train route.

James Tanner to Henry F. Walch, Washington, D.C.: April 17, 1865. Abraham Lincoln Collection.

James Tanner served as a corporal in the 87th New York Volunteer Infantry until he received critical injuries at the second battle of Bull Run; he lost both legs below the knees. He later attended Ames’ Business College where he learned Pitman shorthand, and afterward took a job in the U.S. War Office. Tanner lived at a boarding residence next door to the Peterson house in Washington, D.C., in 1865. When Booth shot Lincoln on April 14, Tanner was summoned to the Peterson house to take shorthand notes during Edwin Stanton’s interrogation of witnesses. Several days later, James Tanner wrote this lengthy shorthand note to a former schoolmate, Henry Walch, comprising a vivid description of the President’s final hours. A later translation accompanies the original note.

James Tanner TLS to John Boos, Washington, D.C.: April 30, 1923. John E. Boos Collection.

John E. Boos created a unique memorial to President Lincoln. From the 1910s to the 1940s, he made a list of people who had known or met Lincoln, contacted them by mail or in person, and compiled firsthand accounts of the President. The Clements Library’s John E. Boos Collection includes over 1,000 of the manuscript letters and typed interviews. Boos bound many of the accounts into subject-specific volumes, including the Lincoln Assassination. This 1923 letter from James Tanner and a copy of a letter he wrote to his mother in 1865 accompany recollections of persons present at Ford’s Theater on the day of the assassination.

Left: Green Room, printed invitation to view Lincoln’s body at the White House, [Washington, D.C.: 1865]. George William Taylor Papers.

Right: A Nation Mourns the Departed Patriot, Statesman, and Martyr, silk badge, [Washington, D.C.: 1865]. George William Taylor Papers.

E. Mack, President Lincoln’s Funeral March, Philadelphia: 1865.

Composers in numerous cities created different funeral marches to commemorate Abraham Lincoln’s death. This sheet music cover includes a black-bordered oval portrait of the President, flanked by American flags. Below the portrait, two women mourn over his flag-draped coffin.

Left: Charles Sumner, The Promises of the Declaration of Independence. Eulogy on Abraham Lincoln, Boston: 1865.

Right: J. A. Arthur, Washington & Lincoln. (Apotheosis.), carte-de-visite, Philadelphia: 1865. Mark A. Anderson Collection of Post-Mortem Photography.

J. A. Arthur photographed and copyrighted this painting by S. J. Ferris, which shows George Washington welcoming Abraham Lincoln into heaven. Washington embraces Lincoln and provides him with a laurel wreath. The image embodies American sentiments toward the two Presidents, one as the founder and the other as the savior of the American Republic. Charles Sumner noted in his eulogy on Lincoln: “the work left undone by Washington was continued by Lincoln.”