Guest post by Sarah Fitzgerald, Book Division volunteer

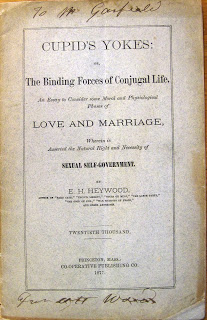

Ezra Heywood was a feminist and abolitionist who edited an individualist anarchist magazine, The Word. He was convicted of violating the 1873 Comstock Act in 1878 for mailing ‘obscene material,’ which consisted of literature attacking traditional notions of marriage, and went in and out of prison until his death in 1893. Heywood’s 1877 essay, Cupid’s yokes: or, The binding forces of conjugal life. An essay to consider some moral and physiological phases of love and marriage, wherein is asserted the natural right and necessity of sexual self-government mentions the passing of the Act forbidding the mailing of ‘lewd’ publications. He knew the risk he was taking in writing about his sexual beliefs.

In the essay, Heywood sets out his beliefs that sexual intercourse is moral whenever the couple feels affection for one another and immoral whenever they do not, regardless of whether the participants are married or monogamous, or not. In his words “The kingdom of heaven supplants all human governments; in it the institution of marriage, which assigns the possession of one woman to one man, does not exist.” He also felt that any couple who felt affection for each other ought to have children together, regardless of who they were married to. Heywood also advocated sexual education, including how to prevent conception by the rhythm method. It was courageous of Heywood to take a stand for sexual freedom in a time when it was against the law, but not all his statements about women are as modern. One reason he gave for his defense of sex outside of marriages was his belief that insanity in unmarried women (hysteria) was due to the lack of sexual intimacy.

Heywood’s feminist convictions have their roots in the ideas of Mary Wollstonecraft, who blazed a path for many feminists in her 1792 book A vindication of the rights of woman:with strictures on moral and political subjects. Wollstonecraft was also suspicious of the unequal treatment of the sexes within marriage. She chose not to marry her lover, Gilbert Imlay, and later she married William Godwin, an anarchist and adherent of the free love philosophy. She had a daughter with Godwin who grew up to be Mary Shelley, another proponent of free love.