With Halloween right around the corner, here at the Clements Library our thoughts have turned to all things spooky that send shivers up your spine. While perhaps not as sinister as ghouls and goblins, the bare human skeleton has a disconcerting effect all its own that lends it symbolic weight.

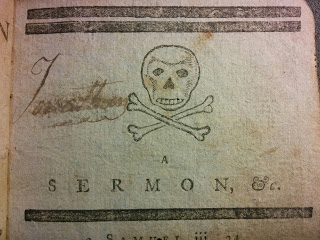

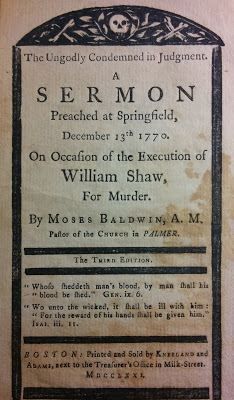

Our Book Division has a sampling of tracts that use the human skull as a tool to emphasize the dire impact of immoral behavior. A sermon preached at the funeral of Joshua Spooner, a man who was “barbarously murdered at his own gate… by three ruffians, who were hired for the purpose by his wife,” was published in 1778. If Pastor Nathan Fiske’s admonishments against this “blackest catalogue of sins” were not enough to deter wayward minds, the publisher included a woodcut of a skull and cross bones to underline the dire consequences awaiting sinners.

|

| Detail from Nathan Fiske, A sermon preached at Brookfield, March 6, 1778: on the day of the interment of Mr. Joshua Spooner (Danvers: E. Russell, 1778), p. 3. |

The image must have resonated with the audience, or at the least with Ezekiel Russell, the publisher, for six years later he included it again in the evocatively named American Bloody Register. The narratives of the “lives, last words, and dying confessions” of notorious high way robbers and pirates are accompanied by the same forbidding skull and cross bones, now amidst the message “See and fear and do no more so wickedly.”

|

| For those interested in pre-1800 gravestones from Northeastern America, the Farber Gravestone Collection is available online. |

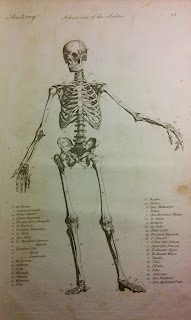

Of course, not all skeletons serve moralizing ends; some function in a more scientific context. Our 1795 New Medical Dictionary features some stunning illustrations of human anatomy, including this jauntily posed skeleton.

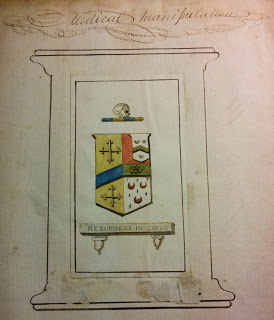

Medical practitioners, for good reason, can be drawn to the skeletal figure as a symbol for their work with the human body. The Clements Library’s Harvey L. Sherwood Memorial Collection includes London apothecary William P. Marshall’s manuscript notes, which he entitled “Medical Manipulation.” His hand-drawn title page includes a crest topped by a human skull. The skeleton’s obvious symbolic link to human mortality makes it an especially appealing addition to this volume of medical information aiming to stem its tide.

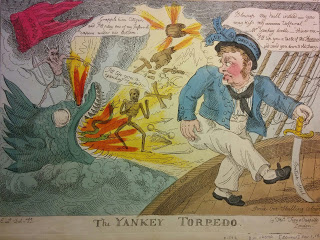

The linkage between the human skeleton and death makes it an apt satirical tool, as well. In this ca. 1813 print by William Elmes, the devil stands astride a sea monster that unleashes a barrage of unholy matter on a British seaman. Lambasting the American’s recent adoption of explosives and torpedoes during the British blockade of New York in the War of 1812, this print uses a skeleton to represent death. Its pugilistic stance further emphasizes how sailors had to face mortal danger, an unnerving prospect in reality even if humorously portrayed here.

|

| William Elmes, The Yankey Torpedo (London: [Thomas Tegg], [ca. 1813]). |

|

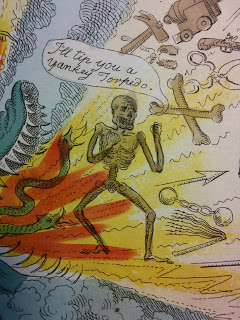

| A detail of the print’s bad-tempered skeleton. |

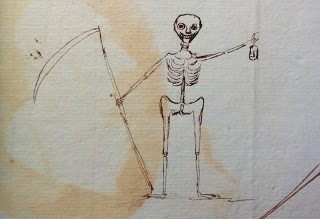

The symbolic weight of the skeleton makes it an appealing figure, even in the more relaxed moments taken up with doodling. In a wastebook in our Constantin Family Papers, a rather pleased looking skeleton appears holding death’s sickle and a bottle of some unhealthy concoction.