Post by Jayne Ptolemy, Manuscripts Curatorial Assistant

As a new semester begins at the University of Michigan, here at the Clements Library we’re highlighting some student maps to celebrate the academic year. The educational benefit of studying geography and copying maps has made them classroom staples, and the pride students feel upon successfully completing a map spans the centuries, too. In 1815, Sarah Butler wrote to her sister about her schoolwork, including “two large Charts… one of America and the other of Europe and my dear preceptress thinks that they are wrote well enough to be framed and I feel much pleased to think that she thinks that it is done so well.”[1] Evidence of children’s investment in geographical studies can be found in surprising places, like this ca. 1825 book, The Elements of Geography Made Easy. Earl Evans inscribed the book twice, and while not an unusual practice, after one he included a revealing addendum: “Eirl Evens is a Bright Boy.” Mastering the arts of geography, much like the children shown in the book’s illustrations, may have helped Earl to feel particularly bright… even if he did happen to misspell his name.

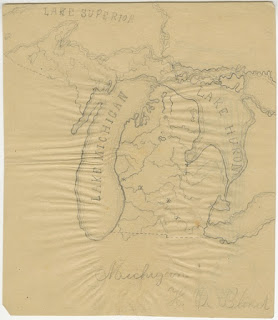

The student creations in the Map Division are made with care, but sometimes they contain mistakes. Take this ca. 1853 hand-drawn map of Michigan and Wisconsin made by H. L. Hobart.

|

| H. L. Hobart, “Map of Michigan & Wiscosin,” ca. 1853. This map was recently adopted by our generous supporter David Kennedy. To learn more about our adopt-a-piece-of-history program, click here. |

We can all empathize with the feeling of frustration Hobart may have felt when he realized he left the “n” out of Wisconsin as he finished his map. Regardless, his work was treasured and preserved through the years, and the error only adds to our emotional connection with the piece. The shared experience of making mistakes and learning from them helps us understand the students that produced these maps.

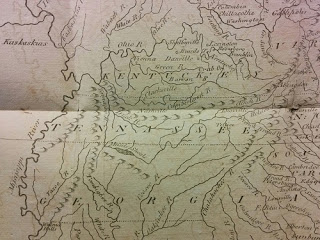

Sometimes the misspellings on maps are not the students’ fault. For example, this recently acquired map from the 1820s features the state of “Tennasee.”

While we may assume this is a student’s phonetic spelling of the state name, it actually appears in this form in widely printed maps that teachers may have had their pupils copying. This spelling can be seen in the map of the United States in the 1801 edition of Carey’s American Pocket Atlas, while the written description of the state uses the typical “Tennessee.”

|

| Detail from The United States of America, in Mathew Carey, Carey’s American Pocket Atlas (Philadelphia: H. Sweiter, 1801). |

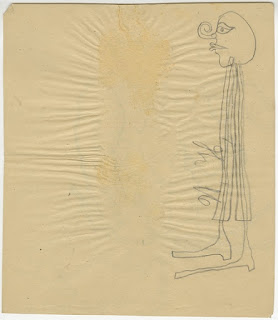

Apparent typos are not the only way we see the students’ direct influence in the maps they made. Sometimes we gain a glimpse of how students dealt with distraction or boredom. Laid into our copy of Harper’s School Geography are a series of hand-drawn state maps made by Henry De Blond in 1884. A whimsical doodle is sketched on the back of his map of Michigan.

|

|

| This map of Michigan, and its accompanying doodle, can be found in the [Henry De Blond state maps], which are laid into the 1882 edition of Harper’s School Geography, donated by James E. Laramy. | |

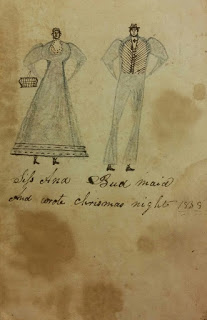

Other drawings can be found in our School Atlas to Accompany Woodbridge’s Rudiments of Geography. Illustrations of men and women appear throughout the volume on blank pages. This particular one, drawn on the back of a map of the United States during Christmas 1838, gives us a glimpse into how this book was used.

Whether or not the children were actively studying geography on Christmas night, they certainly had the book out and were using it for their own purposes. These drawings speak to the tendency of young minds to wander while performing school work.

Of course, not all geographic exercises come in the form of copying maps or studying books. The Clements also has examples of educational games. This 1885 game has a map of the United States printed on a wooden board that can roll up. It includes small pegs for American state “capitals and business centres” with details about the places printed on them to be placed in their correct locations. Intended for “use in schools and in the home circle,” the Norris’ Cyclopaedic Map incorporated play into geographic study.

|

| Detail from Norris’ Cyclopaedic Map of the United States of America, (excepting Alaska) together with adjacent portions of the Dominion of Canada and of the United States of Mexico (New York: W. R. Norris, 1885). |

Hopefully looking at these examples of young people’s engagement with maps has put you in the back-to-school spirit. And students, if you make mistakes or get distracted, remember you are certainly not alone… but also beware that the evidence can be long lasting!

Footnotes:

1.Sarah B[utler] Davis ALS to Eliza Eldredge, 1815 November 11, Sarah B. Davis Letters, Duane Norman Diedrich Collection.